|

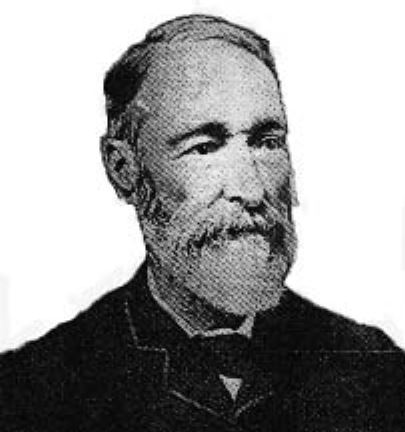

On March 6, 1888, Don José “Pepe” Llulla died in what is now the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans. At the age of 73, Llulla had made himself famous for two things: he was a renowned duelist, and he also owned St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery. Llulla’s life was the kind from which New Orleans legend are spun. He was a valiant Spanish swordsman who frequently took up the mantles of honor and integrity on the field of one-on-one battle. Upon being knighted by the King of Spain, he was gifted a wreath of victory spun from the shining tresses of Spanish women’s hair. He once pulled a machete on a Cuban revolutionary. His legacy, then, is double-edged: Llulla’s contribution to the landscape of New Orleans cemeteries is second only to his impact on the city’s romantic imagination.[1]

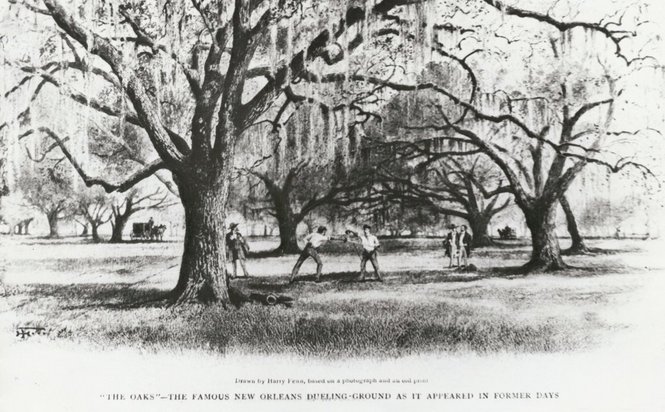

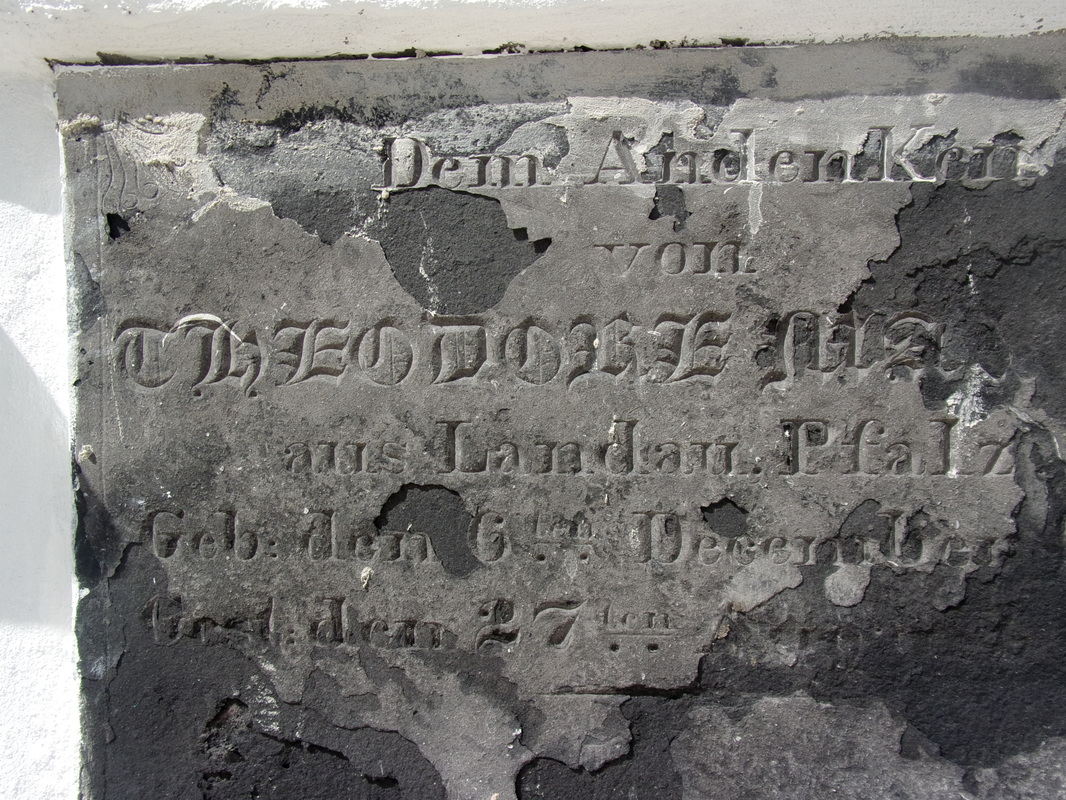

The nature of his work in New Orleans caused Llulla to gravitate toward the art of fencing, which was practiced not only in combat but in private salons. Llulla studied under a local duelist from Alsace named L’Alouiette, whose salon he later took over and became teacher himself. From here, Llulla’s reputation as a witty, cunning, and skilled fencer and duelist only grew. Although additionally skilled with firearms, his weapons of choice were more often swords, foils, and (to a lesser extent) knives. Accounts differ as to how many duels Pepe Llulla actually engaged in (and won), but they generally agree between twenty and thirty matches. Hearn notes that many of these ended not in bloodshed but with the retreat of his opponent. In fact, he suggests that Llulla only actually killed two men. The only match which Pepe had declined was reportedly one in which the opponent chose “poisoned pills” as his weapon of choice – a type of Russian roulette with cyanide – and this only after objection from the duel’s referees. While Llulla’s opponents on the field of honor were of many backgrounds – New Orleans Creoles, Alsatians, Germans, and others – he made special efforts to combat Cubans. The man with the poisoned pills was from Havana. In another instance, a Cuban opponent chose machetes as the weapon of choice, as he believed that such weapons were not available in New Orleans. From the account, it appears as if Llulla instantly produced two matchetes, at which point the Cuban disappeared. Beginning in the 1860s and finally culminating decades after Llulla’s death, the cause of Cuban independence from Spain had a theater in New Orleans. Cuban revolutionaries frequented the Louisiana port and sought support among the Spanish-speaking citizens of the city. Llulla’s passionate Spanish patriotism flared especially against these men, whom he saw as traitors. Reportedly, he posted flyers all over New Orleans in French, English, and Spanish languages, challenging any Cuban revolutionary to duel him personally. Llulla’s reputation and bravado prevented any takers to this challenge, although it did lead to a number of assassination attempts, one of which reportedly occurred in Llulla’s own cemetery, although he escaped unharmed. For his bravery and loyalty, Llulla was formally knighted by Kings Charles III of Spain, who awarded him “a wreath and likeness of himself made from the silken tresses of Spanish ladies’ hair.”[4] Through his lifetime, Pepe Llulla dabbled in many different business ventures. He purchased real estate and ran a logging company. For some time, he staged bull fights in Algiers. Yet he is best remembered as the proprietor of the “Louisa Street cemeteries,” which he likely purchased in the 1840s – although one source states date of purchase as 1857. “One of Our Finest and Best-Managed Burial Grounds” St. Vincent de Paul Cemeteries No. 1 and 2 are located on Louisa Street, near Robertson in the St. Claude neighborhood of New Orleans. Often confused with another set of cemeteries with the same name located Uptown, these cemeteries were likely the parish cemeteries for the Catholic church of St. Vincent de Paul, located on Dauphine Street in the Bywater neighborhood. The exact founding date of this cemetery is quite unclear. Some sources have presumed the property came into use as a burying ground in the 1830s, but an exact citation or primary source is not provided. In fact, the exact year in which Llulla purchased the cemetery remains unclear. On the far periphery of twentieth century studies of New Orleans cemeteries, St. Vincent de Paul experiences the twin historical blows of scant documentation and academic apathy.[5] Despite its present-day low profile, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery flourished under the management of Pepe Llulla. Wall vaults in the cemetery’s oldest sections are galleries for some of the most talented stonecarving of the 1840s and 1850s – the delicate hand-tooled flowers of Florville Foy, ornate German Fraktur by Anthony Barret, inverted torches and wreaths carved by Americo Marozzi and Audré Samonzet are all present. The integrity of these stones surpasses that of even the older, better-known St. Louis Cemeteries, which have been frequently altered over time. Most of these tablets are framed with railings of cast- and wrought-iron, accented with zinc finials. The aisles of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery No. 1 retain the marks of large-scale tomb development. Rows of identically-built structures line the brick-paved walkways, each bearing the alterations and changes in material that would develop over time and use. The society tombs of the United Brethren and Sons of Louisiana (signed by “Joseph Llulla, 1873”) while today faded from their Classical-revival glory, bely the historic grandeur of the landscape. In the 1870s, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery was described as “one of our finest and best-managed burial grounds” by the New Orleans Democrat. By this time, the cemetery had developed into a verdant landscape with reportedly excellent drainage – a constant problem in New Orleans cemeteries. Juniper and cedar trees shaded the aisles, roses and other fragrant flowers grew in the garden lot of the Hermann Lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (no longer present today). Newspapers even took note that families in Uptown New Orleans had begun to purchase lots in St. Vincent de Paul, preferring it to the Lafayette Cemeteries of their home district.[6] Above Left: 1845 tablet in French carved by German carver Vlau. Above Right: 1853 tablet for Cuban native, carved by French carver Florville Foy. Bottom Left: 1862 tablet in German carved by Italian carver Azereto. Bottom Right: 1852 tablet in French carved by Italian carver Parelli. (Photos by Emily Ford) The cultural associations of those who buried loved ones in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery No. 1 and 2 are strikingly diverse. While in other cemeteries it is clear that those with linguistic or national similarities typically utilized the same burying grounds – for example, French-speakers in St. Louis No. 2, Americans in Lafayette No. 1, Italians in St. Roch No. 2 – St. Vincent de Paul represents all walks of life and nations of origin. Tablets in French, English, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and even Chinese line its wall vaults. In addition to the tombs of the French Sons of Louisiana and the Societe Francaise, St. Vincent de Paul was also once home to tombs dedicated to the members of the German Louisiana Wolthatickeits Verein and Italian Tiro al Bersaglio, although both tombs have since disappeared. Pepe Lulla never married, but did have at least three children - Joseph, Jr., Isabella, and Louisa. His two daughters married two brothers - Manuel and Vincente Suarez. Joseph Jr. and Isabella passed away before their father's death in 1888, and he left his estate and cemetery to his daughter Louisa. For the next two decades, the cemetery was under her care and that of her husband Manuel. [8] The landscape of the cemetery shows slowed development and little new tomb construction with the exception of some large, 1920s-style tombs near the Villere Street wall vaults. St. Vincent de Paul No. 2, which sits between Desire and Piety Streets, shows an explosion of coping construction, likely between 1910 and 1930. It was during this period that two of St. Vincent de Paul’s more famous “residents” were buried, the African American spiritualist leader Mother Catherine Seal and the Romany “queen” Marie Boscho.[7] In 1910, ownership of the St. Vincent de Paul Cemeteries transferred to the Stewart family. Stewart Enterprises later became the second-largest funerary corporation in the world, which also owned Metairie-Lakelawn Cemetery and Mount Olivet Cemetery in Gentilly. During this time, St. Vincent de Paul No. 3 was heavily developed, including a large community mausoleum on Villere Street. In 2005, a service building and other property belonging to St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street was damaged in Hurricane Katrina and was demolished. In 2013, Stewart Enterprises was purchased by first-largest funerary corporation Service Corporation International (SCI), who now owns St. Vincent de Paul Nos. 1, 2, and 3. A Threatened Legacy In 2015, SCI announced that it would spend $7.2 million in “improvements” to its recently-acquired cemeteries in New Orleans, including St. Vincent de Paul. Unfortunately, these improvements have dangerously ignored preservation ethics and best practices. For St. Vincent de Paul No. 1, this has meant encasing the Louisa, Urquhart, and Piety-street wall vaults in heavy, inappropriate Portland cement-based stucco, as well as treating its 140 year-old tablets with harsh bleach and pressure washing. Perhaps most troubling, the delicate ironwork rails that once framed each wall vault have been torn out and lay entangled in the cemetery’s aisles. The extent of the damage to these vaults will only be truly visible in decades to come, when material constrictions, lack of ventilation, and material weight will destroy the historic fabric underneath. The legacy of Pepe Llulla is one of romance and anachronistic bravado, of sword fights and burning candles on marble tombs through the night of All Saints’ Day. The place of the cemetery he built in New Orleans’ larger funerary landscape is much more important than it has been given credit for. If this fact is not soon realized, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery will be lost before it is ever truly understood. [1] The vast majority of knowledge regarding Don Pepe Llulla comes from the observations of Lafcadio Hearn, whose documentation of Llulla appears to have influenced all later writing on the man.

Lafcadio Hearn, and S. Frederick Starr, ed., Inventing New Orleans: The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 49-60. [2] Ciaran Conliffe, “Jose ‘Pepe’ Llulla: The Gravedigging Duelist,” http://www.headstuff.org/2015/03/jose-pepe-llulla-the-gravedigging-duellist/ [3] Hearn, 52. [4] “Death of Senor Don Jose Llulla,” States Item, March 7, 1888, p. 4. [5] Christovich, Huber, et. al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1974), 32. [6] “A Mournful Holiday. How All Saints’ Day Was Celebrated in Our Cemeteries,” New Orleans Democrat, November 2, 1878, p. 8; “All Saints’ Day. An Outpouring of All Our Population to Decorate the Graves,” New Orleans Democrat, Nov. 2, 1878, p. 1. [7] Author Zora Neale Hurston wrote an excellent piece on Mother Catherine, which can be read here: http://www.fiftytwostories.com/?p=1068. [8] Thank you to descendants of Pepe Llulla - Nancy Suarez Gustitus, Linda Suarez Lee - and Marga Llull for correcting and clarifying the succession of Pepe Llulla, Louisa Llulla, and the Suarez brothers.

23 Comments

Janice Broussard Coari

3/23/2016 09:24:12 am

Loved your articles. Well written and great photos. Thanks for your dedication and hard work.

Reply

Linda Suarez Lee

8/4/2016 12:54:44 pm

Loved reading this. Have some additional info if interested. Pepe Llula is my great, great granfather. His daughter Luisa married Manuel Suarez. Manuel, according to an obituary I have, took over as Sexton of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery after the death of Llula in 1888.

Reply

8/5/2016 08:32:28 am

Dear Linda,

Reply

Nancy Suarez Gustitus

10/19/2016 02:37:49 pm

Not to muddy the waters but perhaps the Suarez signature is not just that of Manuel. Manuel's younger brother Vincente also worked for Llulla and was married to his daughter Isabella. So brothers married sisters. Isabella died in 1880 and sometime thereafter Vincente remarried and moved to Chicago. I am the great granddaughter of Vincente. Not sure if you are still researching anything but feel free to contact me.

Nancy Suarez Gustitus

10/19/2016 02:41:25 pm

Linda, your great grandfather and mine (Vincente) were brothers. I am working with two of the Llulla relatives in Spain contributing to a family tree they started. If you are interested, please contact me. I believe you will receive my email address thru this site?

Reply

Emily Ford

10/20/2016 10:04:09 am

Dear Nancy,

Janice Broussard Coari

11/6/2016 03:00:37 pm

Hi and thanks again for your great work on st. Vincent de Paul cemeteries. I have u covered documents that show Pepe llula and my great grandfather were friends and business associates. My great grandfather Juan Preto y Frederick was. Also from Majorca, Spain. Juan died in 1872 and I recently obtained a copy of the original deed for the vault signed by Pepe Llula. I can scan. And send you a Copy if you'd like to see it. I was a.azed to find out I am a part owner of the vault as the deeds were recorded "in perpetuity" so they were passed down to the heirs. Very pleased to know this, but sad to see the historic aspect is disappearing. I have 5 generations buried there, including my brother and father up to my 2 x great grandparents. Sad state of affairs. Thanks for the March 2016 pics. I am afraid to visit there alone. Dangerous area😑live your work, thanks so much.

Reply

Emily Ford

11/7/2016 12:18:24 pm

Dear Janice,

Reply

Daria Felice Palmer

10/19/2018 09:44:56 am

Dear Janice,

Reply

Janice Broussard Coari

4/4/2019 12:04:14 pm

I obtained the original deed to the vaults and tomb in 1991 when my uncle passed away .You can visit the office at greenwood cemetery on Canal Blvd. for copies of deeds. They don't answer their phones the best way is to go down there in person as they have all the records of St . Vincent de Paul. Good luck to you.

Marga Llull Pons

4/9/2023 04:55:59 am

Dear Janice. I am Marga Llull, my cousins Nanci and Linda, attest that I am making a family tree of the Llulls. But it is also true that I am interested in the Menorcans who emigrated to New Orleans. (a tremendous story) Was your ancestor Menorcan? I could help you find your roots. We do it for the love of art and genealogy. If I'm right, your relative Juan Preto Fedelich was born in Es Castell, Menorca,...

Reply

2/16/2017 12:20:46 am

The degree of the harm to these vaults might be genuinely noticeable in decades to come, when material tightening influences, absence of ventilation, and material weight will demolish the notable texture underneath.

Reply

4/4/2019 03:22:18 am

Wonderful article!

Reply

6/9/2020 09:57:43 am

Are burial records available anywhere? My GGrandfather was buried there in 1892, died Jan 4, 1892.

Reply

Emily Ford

9/27/2020 05:21:21 pm

Dear Mr. McLaughlin,

Reply

Michael Edward Hingle

9/25/2020 10:34:40 pm

Thank you for this article. There are Hingle family members spread out throughout number 1 and 2.

Reply

Emily Ford

9/27/2020 05:19:44 pm

Dear Mr. Hingle,

Reply

9/27/2020 11:14:09 am

Could someone tell me where Jose "Pepe" Lulla's tome is located in the cemetary? I plan on visiting, I have an ancestor that was friendly with Pepe Lulla back in the 1850 time era. My Great Grand Father's Uncle was a respected New Orleans Blacksmith and shoed some of Mr. Lulla's horses and repaired his carriage. His shop was near what is today Audobon Park.

Reply

Emily Ford

9/27/2020 05:23:09 pm

Dear Mr. Hill,

Reply

Emily Shamburger

10/11/2020 03:32:18 pm

I live 2 blocks from this cemetery and just walked through today. I will have to go back in light of this article to take note of some of the information you pointed out. This is very interesting and well-written, thank you!

Reply

Bryan W Bordelon

6/26/2023 11:17:29 am

Emily,

Reply

Emily Ford

6/27/2023 06:43:47 pm

Hey Bryan,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly