|

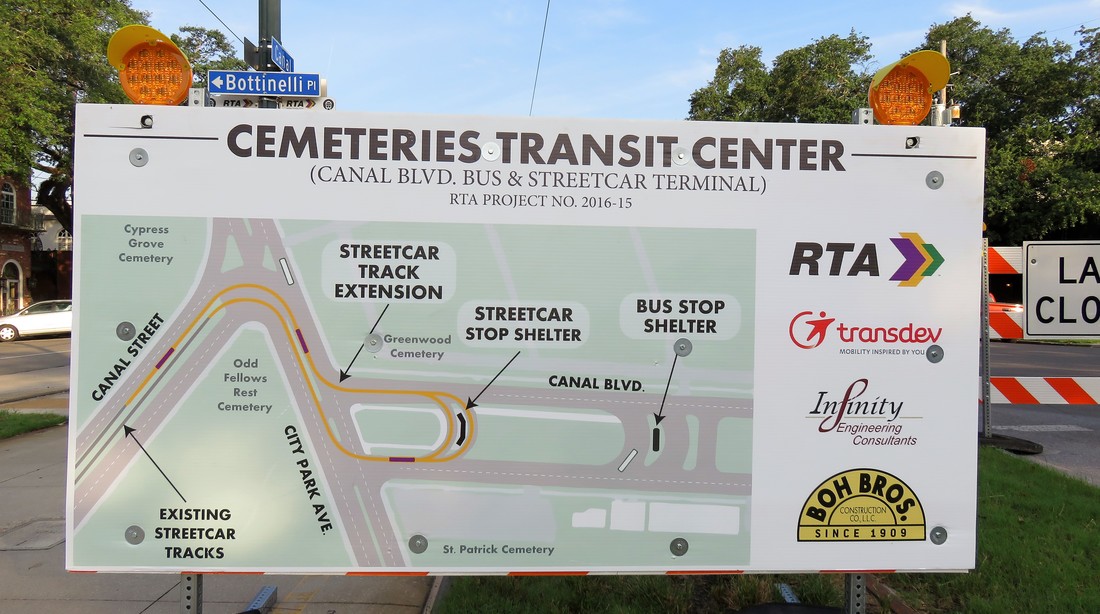

Beginning July 2017, New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) will be executing a significant construction project at the intersections of Canal Street, City Park Avenue, and Canal Boulevard – an area known simply as “the Cemeteries” by streetcar riders and New Orleaneans in general for more than a century. The construction project will extend the Canal Streetcar across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard in a turnaround that will streamline public transportation (see the diagram above). This is first successful attempt at creating a streetcar turnaround at this intersection, which is notoriously confusing and historically jammed with traffic, owing to an odd dog-leg where Canal Boulevard and Canal Street meet City Park Avenue. Fifty years ago, RTA made a similar attempt to connect Canal Boulevard and Canal Street – although that earlier design necessitated the demolition of Odd Fellows Rest Cemetery. Fortunately for New Orleans cemetery heritage, this plan was scrapped and the cemetery was saved.[1] This tangled intersection of New Orleans thoroughfares, joined with the Pontchartrain Expressway (Interstate 10), is the site of a dozen different New Orleans cemeteries ranging in founding dates from 1840 to 1973, and ranging in background from elite city of the dead to humble potter’s field. The intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is an essential crux of New Orleans history in almost every way. It is a heart of metropolitan development and architectural expression without compare. Over the next month, Oak and Laurel is taking a look at the history of the Canal Street cemeteries and their environs, beginning with the history of the land itself.

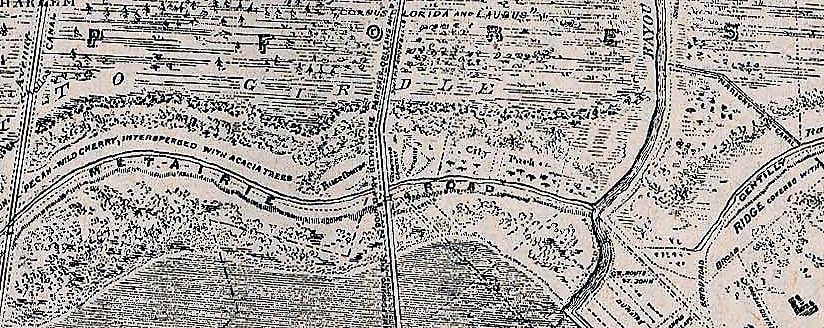

Until this time, commercial navigation between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain utilized Bayou St. John and the Carondelet Canal. The Carondelet Canal was dug in 1794 and extended Bayou St. John to what is now Basin Street – named so for the turning basin located there. The Carondelet or “Old Basin” Canal had disadvantages. Specifically, its age made it less practical, and its location meant its primary beneficiaries were Creoles and other established residents of the former colonial city.[2] Competition between the old French-speaking order and the American interests that populated the city after the Louisiana Purchase motivated investment in a new canal. In 1831, the New Orleans Canal and Banking Company was founded by the Maunsell White and Beverly Chew with the backing of the state of Louisiana. The company was formed with the specific goal of establishing a “canal from some part of the city or suburbs of New Orleans, above Poydras street to the Lake Pontchartrain.”[3] Construction on the New Basin Canal began in 1832, although a terrible cholera epidemic held up its progress that year. The construction of the New Basin Canal was overwhelmingly fueled by the labor of Irish immigrants. Beginning in the 1830s and intensifying in the next decade, migration from Ireland to New Orleans helped make the Crescent City the second-largest port for immigrants in the country. Newly-arrived Irishmen typically came from agricultural backgrounds and sought manual labor in their new city. Tragically, the enormous labor demand and barbaric conditions of hand-digging the New Basin Canal caused thousands of deaths. Sources refer to daily deaths in the trenches from illness and exhaustion, the fallen laborer buried in the soil along the canal as work progressed. The construction of the New Basin Canal defined the Irish experience in New Orleans.[4] The New Basin Canal began at a turning basin along Triton Walk, approximately the present location of the Union Passenger Terminal in the Central Business District. It extended northwest near what is now Carrollton Avenue and turned more northerly from there, meeting Lake Pontchartrain at what is now West End Boulevard. If this route sounds vaguely like the route of Interstate 10 from the Crescent City Connection to the I-10/610 merge, that’s because the Pontchartrain Expressway very closely replaced the New Basin Canal route in the mid-twentieth century.

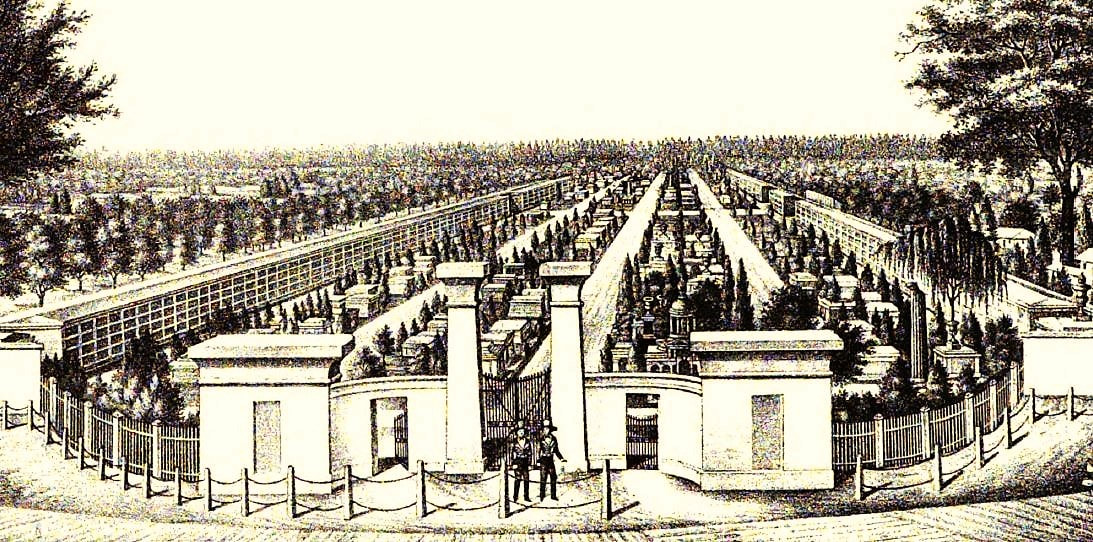

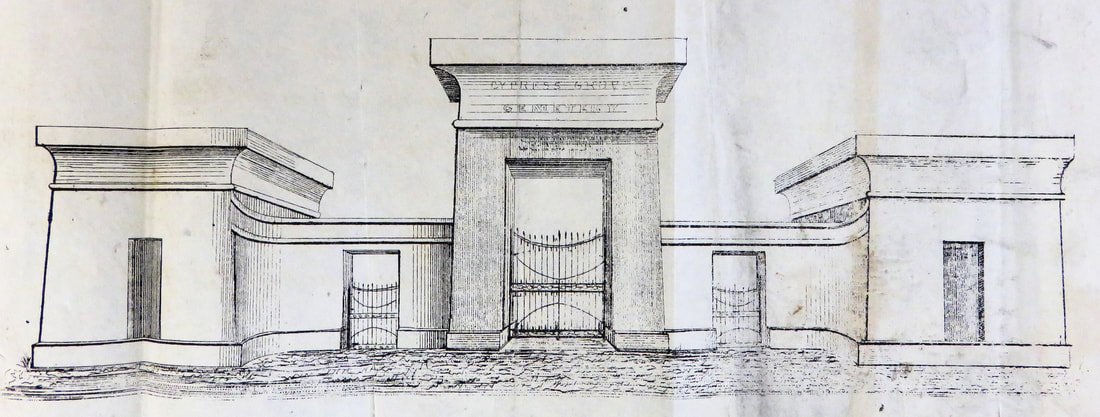

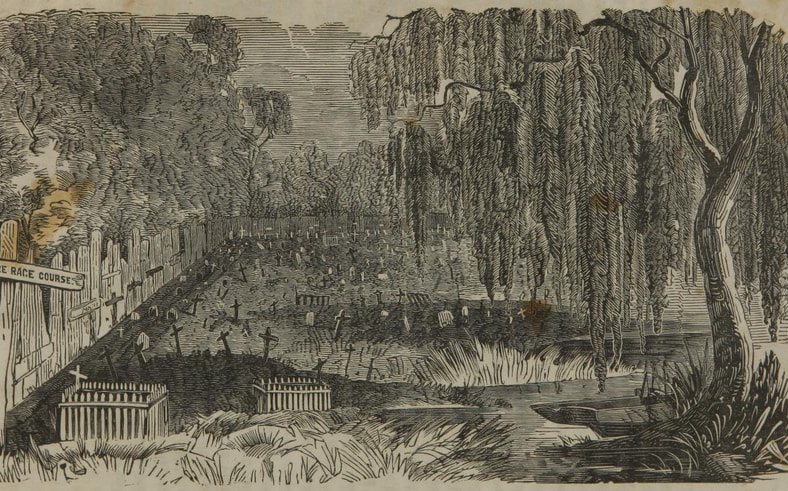

While newcomers to the city found in the Shell Road and New Basin Canal a rural retreat possibly reminiscent of home, these same people from the Northeast, from Ireland, from Germany, and elsewhere, found no cemetery in New Orleans that could be so reminiscent. For the next sixty years, these people would shape this area into such cemeteries.[5] 1840: Cypress Grove Cemetery From the time of the Louisiana Purchase through the 1840s, immigrants from all over poured into New Orleans. As they brought their bodies and livelihoods, they brought their culture and traditions. From Creoles of color from San Domingue, New Orleans gained the shotgun house. As for the thousands of immigrants from the Anglo-Protestant North who came to New Orleans, New Orleans gained from them wire-cut Pennsylvania brick, Anglo-American concepts of landscape design, and the idea of the rural garden cemetery. The rural cemetery movement arose in the northeast in part from the contemporary expansion of cities. Advances in industrialization within the urban landscape created in city-dwellers a longing for the countryside. Furthermore, this same industrialization advanced the American middle class in such a way that recreation was newly defined. Inspired by English landscape design, the rural cemetery was the predecessor to the public park – in fact, Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed one such cemetery in California. This shift in the appearance and purpose of cemeteries coincided with many American cultural movements like Romanticism, the definition of the middle class, and the “beautification of death period.” Northern Americans who moved to New Orleans were inspired by what they saw at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and many more. These were cemeteries that were designed instead of planned, with undulating pathways that strolled past weeping willows and reflecting pools. This was the rural cemetery movement, a great leap in the history of cemeteries that would change the American perception of death forever. This contrasted deeply with the Francophile and Creole cemeteries that had developed in New Orleans to this time – densely packed “cities of the dead” with few if any landscape features. St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 was not planned out by lots or aisles and instead haphazardly developed into the necropolis it became. After St. Louis No. 1, Girod Street Cemetery, St. Louis No. 2, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 (1822, 1823, and 1833, respectively) were planned into square and aisles, but remained cemeteries set in urban landscapes. The cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would be a departure from this context. On April 25, 1840, the first cemetery at the intersection of Canal Street and Metairie Road was officially opened. Cypress Grove was owned and operated by the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association (FCBA) and, although the cemetery would be open to all burials, it would be dedicated to the memory of New Orleans’ volunteer firemen. The dedication ceremony of Cypress Grove included a march of nearly one thousand firemen, clergy, and prominent citizens marching through downtown New Orleans, each wearing mourning bands and a few carrying urns of the ashes of their martyred comrades. The procession boarded the Nashville railroad at the foot of Canal Street and rode to the end, where the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove’s entrance would have stood almost completely alone within the undeveloped landscape. Among the martyrs honored that day was Irad Ferry, the “first martyr,” who perished in the line of duty on New Year’s Day 1837. Originally buried in Girod Street Cemetery, Ferry’s remains were relocated to Cypress Grove as the cemetery’s first burial, beneath a marble sarcophagus topped with a broken column which was designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and constructed by stonecutter Newton Richards. In a nearby tomb constructed for this purpose, the remains of eleven additional firemen were buried.[6]

It would seem almost superfluous to set for the advantages of this rural cemetery. The rapid growth of our city has already encroached upon the tombs of its fathers, and the sacred relics of the dead have been compelled to give way to the cold and selfish policy of speculators, and the intrusion of business; and the solemnity of the grave yard is disturbed by discordant shouts of merriment, and the baleful proximity of the dissolute.[8] (To learn more about Cypress Grove’s history, check out our blog post “Lost Landscapes of Cypress Grove,” Part 1 and Part 2) Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 or Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2 Cypress Grove Cemetery may have extended across Bayou Metairie and through what is now Canal Boulevard. It is true that a cemetery was once present in this space. However, the cemetery is referred to in records as both “Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2” and “Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2.” This potter’s field, which records suggest was dominated only by below-ground burials of the indigent, is referred to in at least one record as belonging to the Firemen’s Benevolent Association, but leased by Charity Hospital for the burial of deceased patients.[9] Over the next century, Cypress Grove No. 2 would accept thousands of indigent burials and become an on-again, off-again bone of contention in this funerary landscape.[10] Next week, we will explore the 1840s as new cemeteries are founded, namely St. Patrick’s, Dispersed of Judah, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest. [1] “End to Canal ‘Dog Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1; “Planners Revive Canal St. Cut-off,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1963, 17; “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, July 3, 1964; “City Abandons Cemetery Suit,” Times-Picayune, December 12, 1972, 9.

[2] Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2008), 30, 135. [3] T.P. Thompson, “Early Financing in New Orleans: Being the Story of the Canal Bank, 1831-1915,” Publications of the Louisiana Historical Society, Vol. VII (1913-1914), 24. [4] Laura D. Kelley, The Irish in New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2014), 32-36. [5] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 132-133, 139-140; David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 44-46. [6] Thomas O’Connor, ed. History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FMBA, 1890), 70-71. [7] “Firemen’s Celebration in New Orleans,” Galveston Daily News, March 6, 1869, 1. [8] Firemen’s Charitable Association, Report of the Committee of the Firemen’s Charitable Association, on the Cypress Grove Cemetery (New Orleans: McKean, 1840), 4. [9] Henry Rightor, Standard History of New Orleans, Louisiana (New Orleans: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900), 265. Rightor’s 1900 history refers to this cemetery as Charity Hospital No. 2. [10] Peter Dedek, The Cemeteries of New Orleans: A Cultural History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 61, 77.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly