|

Wherever you are in the South this year, there is a living history event in a cemetery near you. It’s that time of year again! The weather is cooling down, the pumpkins are in their patches, and our minds turn toward the ethereal, mysterious landscapes of cemeteries.

It’s also the time of year when a lot of preservation, heritage, and city commerce groups hold annual cemetery fundraising events in the form of living history tours. Events like these connect the public with historic cemeteries in a unique way – visitors walk through the cemetery, often at night or twilight, and meet the “residents” of the cemetery. Through drama (and sometimes music), visitors can connect with the importance of the cemetery to local history and culture. Living history tours are also a whole lot of fun! Wherever you are in the South this year, there is a living history event in a cemetery near you. It might be Natchez City Cemetery’s annual “Angels on the Bluff” tour, a large-scale event that sells out every year, as does Oakland Cemetery’s “Spirits of Oakland” program in Atlanta. But it also might be a smaller event hosted by a local historical society. Check out the listings below to plan your cemetery visit – it makes a great date night or family outing.

1 Comment

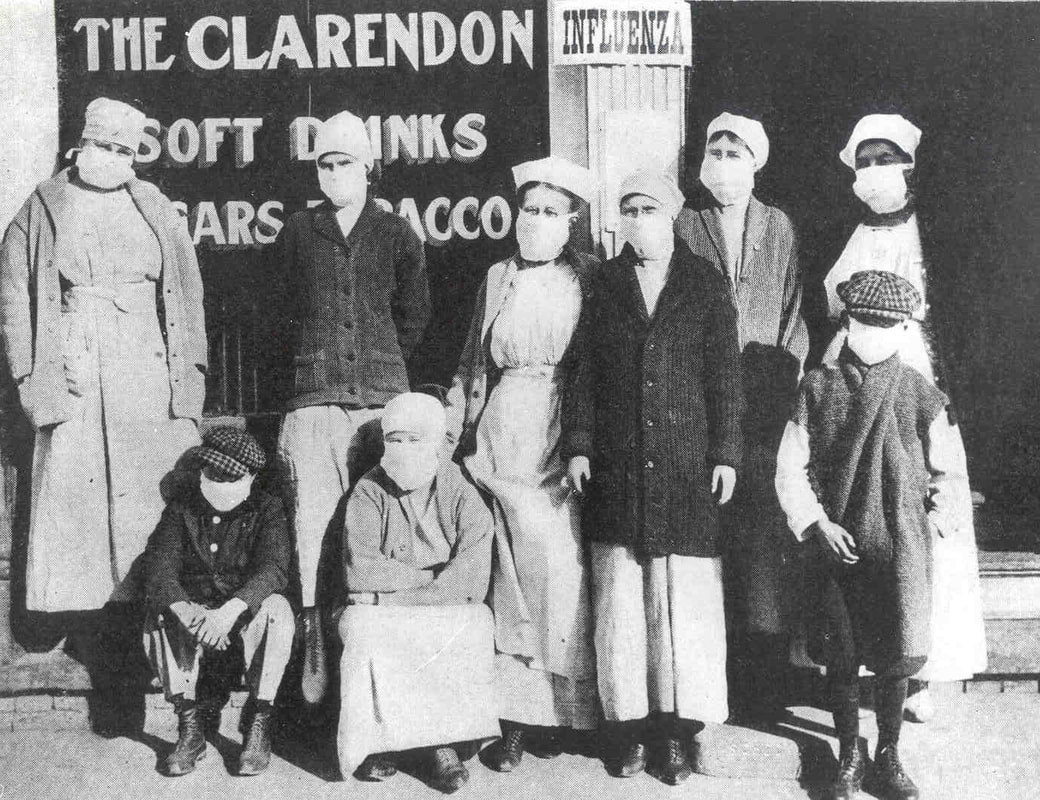

How New Orleans weathered one of the greatest plagues in history. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a worldwide emergency like that which took place in 1918. Modern-day fiction and sci-fi writers have materialized similar fears – there is no shortage of post-pandemic fiction. For example, the HBO series The Leftovers posits a world in which two percent of the world’s population has vanished, the Max Brooks novel World War Z injects zombies into a frighteningly realistic image of how civilization would handle pandemic catastrophe. The list goes on. But we so often forget that something like this did happen. In 1918, a strain of pandemic influenza swept the globe three times, infecting millions and killing five percent of the world’s population. Medical science today cannot pin down exactly where it began. One prominent theory states that H1N1 influenza began with swine farms in Haskell County, Kansas in late January 1918.[1] Like other incidents of mutated influenza virus “jumping” from livestock to humans, it could have fizzled out in the local population. Yet nationwide mobilization in response to the United States’ entry into World War I meant that military camps were ubiquitous and population movement intensified. Influenza was transported to Camp Funston, Kansas, where it spread to other camps, other towns. The first wave of influenza traveled from the United States to Brest, France, in April 1918. Within the next month, it spread to Spain. Spain, neutral during World War I, was less likely to censor press reports of the disease. Hence, although the U.S., Britain, and France saw just as many cases of influenza, such incidents were not reported. The uneven press coverage created the appearance of the disease originating in Spain, giving it the incorrect moniker “Spanish Influenza.[2]” Influenza was documented in China and India by May 1918. The spring wave, however, was comparatively mild. The second wave of Fall 1918 would be devastating. As the summer of 1918 wore on and Allied victories in Europe continued, state and federal medical officials assumed disaster had been averted.

Attempts to quarantine the sick and curb the spread of influenza were often thwarted by the pressures of total war. In one especially salient instance, insistence from upper-crust social circles in Philadelphia caused medical leaders to allow a War Bonds parade to take place, despite the mounting evidence of an influenza epidemic. New cases of the illness soared in the days after this large public gathering. In metropolitan areas, the flu jumped from military to civilian populations, and then spread.

One hundred years ago this month, influenza arrived in New Orleans. Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC maintains an informal database of cemetery vandalism incidents around the world based on news reports. From online journalistic alerts, each report of a vandalism incident is cataloged for location, motivation (if one is identified), number of markers affected, estimated repair costs (if identified) and other factors. The data below is based on this database, cataloged from January to December 2017. It must be noted that cemetery vandalism is often unreported to local press. Our database cannot include unreported vandalism and does not represent the most comprehensive total of vandalism incidents. Instead, it provides a snapshot of some incidents and issues. In 2017, 105 individual incidents of cemetery vandalism were reported to local press across the United States. While the tally of individual incidents, ranging from New York to Hawaii, Florida to Oregon, is significantly less than those reported in 2016 (184 incidents) the total number of headstones and markers affected increased from 1,811 to 2,353, and estimated repair costs reported by cemetery authorities increased from approximately $488,000 in 2016 to approximately $1,766,000 in 2017. Cemetery vandalism is a much more common occurrence than it is commonly understood to be. Each year, hundreds of cemeteries experience loss and damage resulting from stolen grave goods, toppled stones, and graffitied markers. As we noted in our 2016 post on cemetery vandalism, the motivations for such acts vary widely. In many cases, acts of vandalism can be explained by adolescent antisocial behavior – “kids” knocking over headstones for fun or as an expression of control. But in so many other cases, vandalism has a deeper motivation as an expression of political or racial undercurrents. In 2017, racial, religious, and politically motivated cemetery vandalism was pushed to the forefront of American news coverage. In our recap of 2017 in cemetery vandalism, we review incidents of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents, and the community response that helped cemeteries recover. After August protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, incidents of cemetery vandalism targeting Confederate monuments increased. From this point, we will also discuss cemetery vandalism incidents outside the United States with an eye to similarities of motivation. Yet despite 2017’s increases in cemetery vandalism severity, responses from law enforcement may have increased in efficacy. A number of vandals who perpetrated cemetery crimes in 2016 were identified and apprehended this year, and responses have grown more robust. Anti-Semitic Cemetery Vandalism In February 2017, two Jewish cemetery vandalism incidents became national news. Outside St. Louis, Missouri, approximately 175 headstones at the Chesed Shel Emeth Society Cemetery were toppled. Within a week, 100 headstones at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania were also toppled. Vandalism incidents in which more than one hundred headstones are affected are not entirely unusual. However, the two incidents in Philadelphia and St. Louis occurred concurrently with popular malaise around the specter of anti-Semitism – dozens of false bomb threats were made by phone to Jewish community centers around the country in the previous month. When these two cemeteries were vandalized, national and local response was enormous. While the perpetrators in either incident have yet to be apprehended, and the St. Louis incident was not initially pursued as a hate crime, these two cemeteries became rallying points for resistance to anti-Semitism. The incidents also turned the public eye to the larger issue of cemetery vandalism in such a way that affected future responses to such incidents. Unfortunately, these two large-scale incidents were not the only examples of anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism to occur in the United States in 2017. In January, two young women and a young man (ages 19, 16, and 20 years old, respectively) were arrested for anti-Semitic graffiti at a cemetery in Scottsburg, Indiana. Also in January, anti-Semitic and anti-police graffiti was found at Oak Grove Cemetery in Hyannis, Massachusetts – an incident that was investigated as a hate crime. Additional incidents in Rochester, New York, and Melrose, Massachusetts in March and July (respectively) were so investigated. In May, another cemetery in Philadelphia was the victim of what police investigated as an anti-Semitic hate crime.

In fact, money raised to aid Mount Carmel and Chesed Shel Emeth exceeded their needs. Some money raised in Missouri was sent to other St. Louis-area cemeteries to help improve security. Other excess funds were earmarked for other Jewish cemeteries, including Golden Hill Cemetery in Lakewood, Colorado. The state legislatures of New York and Pennsylvania discussed raising criminal penalties against those convicted of cemetery vandalism. While New York did see a threefold rise in cemetery vandalism claims to their state cemetery preservation fund, the state declined to increase penalties. In July 2017, the state of Pennsylvania did increase penalties, including a $2,000 fine and possible 30 days imprisonment. Other Religious and Culturally Motivated Vandalism In general, religious and culturally-motivated cemetery vandalism increased from 2016 to 2017. While in 2016 a number of African-American cemeteries were targeted for race-based vandalism, such crimes appeared to target other groups in 2017. In August, newly-established Al Maghfirah Cemetery outside Minneapolis, Minnesota was vandalized with swastikas and menacing spray-painted messages. The Federal Bureau of Investigation was notified and began investigation. Also in August, Cypress Hills Cemetery in Glendale, Queens, New York was vandalized by three young men who spray painted anti-Muslim, anti-Asian, and anti-African American graffiti on cemetery walls. In this case, the perpetrators were filmed by surveillance cameras. The three men were arrested in October 2017 and charged with hate crimes. Confederate Monuments After the mass murder of nine worshippers at Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015, national dialogue turned to the removal of Confederate monuments throughout the country. The Confederate monuments in question were, in almost all instances, those set in public space and not in cemeteries. For example, New Orleans city council voted to remove four public Confederate monuments in December 2015, but excluded Confederate monuments in cemeteries from discussion. In 2017, public discourse regarding Confederate monuments in New Orleans did include cemeteries, but only as possible locations that removed monuments could be relocated. In 2016, only one incident of vandalism targeting Confederate monuments took place, in Raleigh, North Carolina. After the shocking protests and violence that took place at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017, targeted cemetery vandalism increased. Five incidents of vandalism of Confederate monuments took place in United States cemeteries after Charlottesville, as well as one additional incident involving a Union soldier monument in California. In Los Angeles, California, a Confederate monument placed in Hollywood Forever Cemetery by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1925 was graffitied with the word “NO” in permanent marker. Shortly afterward, the UDC removed the monument and placed it in storage. Other cemeteries increased surveillance and security after the Charlottesville protests in anticipation of targeted vandalism. Such was the case in Springfield National Cemetery in Missouri. However, during a shift change between security details, red paint was splashed across a monument to a Confederate major general. This incident was tied in newspaper reports to a recent statement by Missouri state legislator Warren Love, who stated that those who vandalize monuments should be “hung high with a rope,” prompting calls for Love’s resignation. Other incidents took place in Fairfax, Virginia, and Columbus, Ohio, where a zinc monument placed in 1902 was pushed from its pedestal and shattered. Its detached head was stolen. At Woodlawn Cemetery in West Palm Beach, Florida, a 1941 Confederate monument was tagged with multiple messages in red spray paint. Most recently, Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Rome, Georgia, was targeted when a granite statue was pushed from its pedestal and repeatedly struck with an unknown instrument. Catching Vandals: “Who Does Something Like This?” In our 2016 vandalism blog post, we noted that is extremely unlikely for cemetery vandals to be identified and apprehended. In 2017, arrest of cemetery vandals was slightly more likely than in the year previous. Most notably, the investigation into 2016 anti-Semitic vandalism of Beth Shalom Cemetery in Warwick, New York, came to a close in October when 18 year-old Eric Carbonaro was arrested for the incident. Carbonaro was charged with a hate crime and tampering with physical evidence, after he deleted photographs of the vandalism from his phone. Carbonaro was found to have conspired to commit the vandalism with two other people, one of whom made a meme of Carbonaro’s face under the caption “Secretly spray paints Jewish cemetery and gets away with it.”

The cemetery owners claimed the $15,000 in damage would be covered by the cemetery itself. Moreover, the cemetery held a cookout for families whose property had been damaged, at which they were given new flowers and flags to place on their lots. In September 2017, more than thirty of a total one hundred monuments were toppled in Bohemian Pecenka Cemetery in Marysville, Kansas. The cemetery was cared for by the local high school 4H, whose members overheard their five teenage classmates admitting to the act and turned them in. In October, a Cordova, Alabama man was arrested for vandalizing Mt. Carmel Cemetery. In an interesting attempt at community policing, the vandal, 23 year-old Joshua Hicks, was brought to the cemetery to meet families whose property he’d damaged. Hicks explanation for why he vandalized the cemetery: “… he likes to get intoxicated, gets bored, and likes to vandalize.” Other arrests for cemetery vandalism in 2017 included the June arrest of an adult man who repeatedly vandalized Historic Japanese Cemetery in Oxnard, California. This man was known to the cemetery and was understood to have mental health concerns. The cemetery declined to pursue charges. A 48 year-old man in Kahoka, Missouri was arrested for removing marble closures from a mausoleum. In Schenectady, New York, a 43 year-old man was arrested for scratching his “rapper’s name” into a headstone at Vale Cemetery. International Cemetery Vandalism Oak and Laurel’s cemetery vandalism database includes all cemetery vandalism-related reports written in English. This usually includes the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, where cemetery vandalism is frequently reported. For example, at Berri Cemetery in Riverland, South Australia, three boys aged 9, 10, and 11 were turned in to the cemetery after their mother found out they had been toppling headstones. As in 2016, vandalism in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland continues to be an issue associated with sectarian conflict. In January 2017, a man in his 50s was arrested for vandalizing the monument of Irish politician Éamon de Valera in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. In addition to criminal charges, he was banned from the cemetery. In the April anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, a remembrance wall at Glasnevin was splashed with paint.

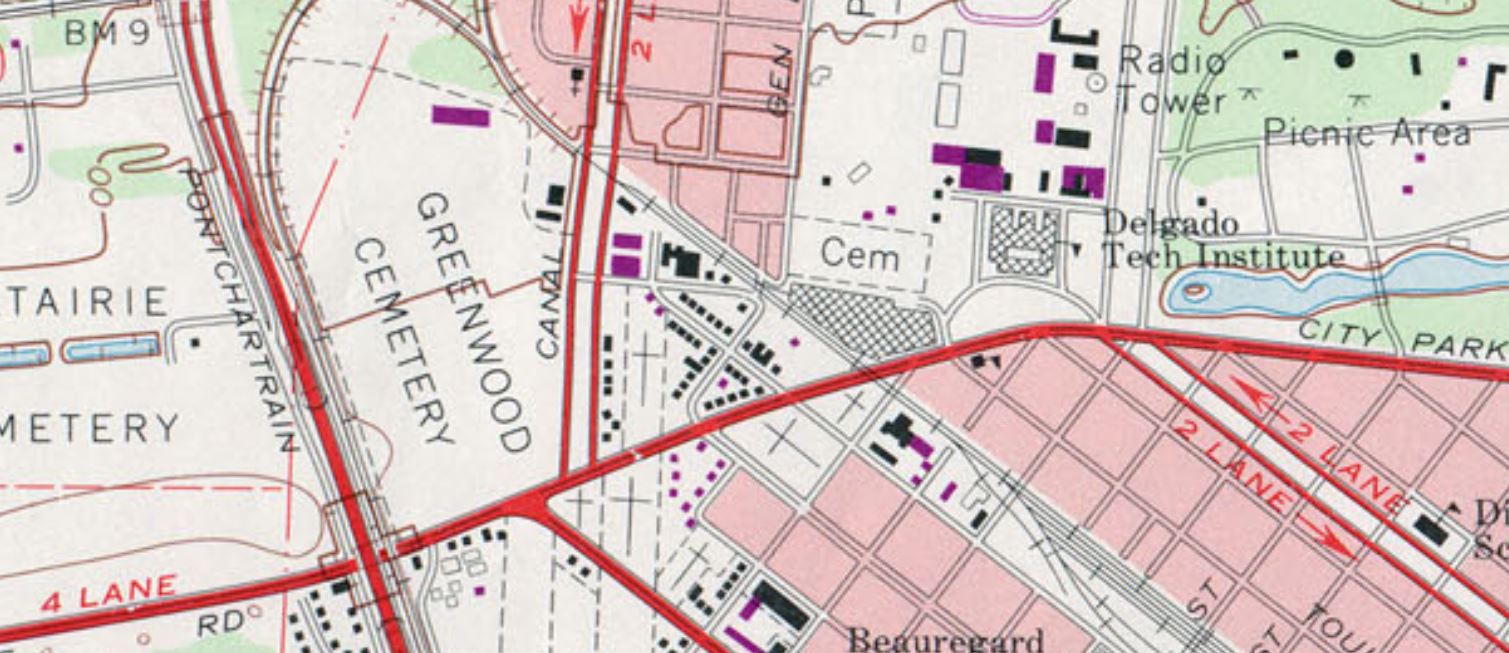

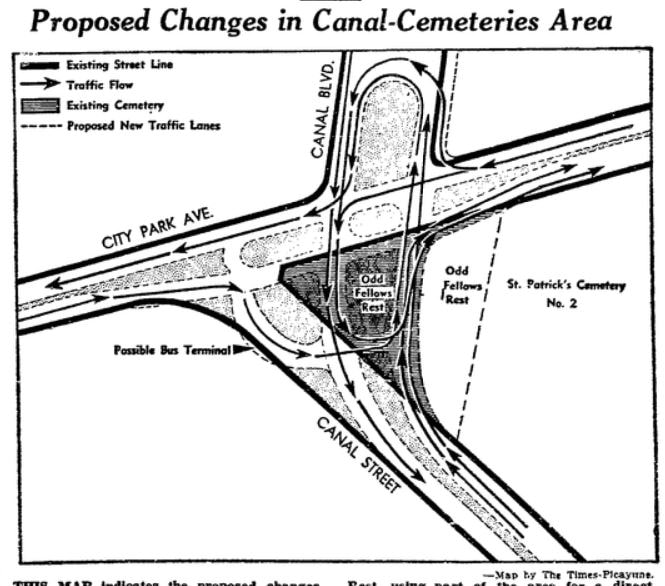

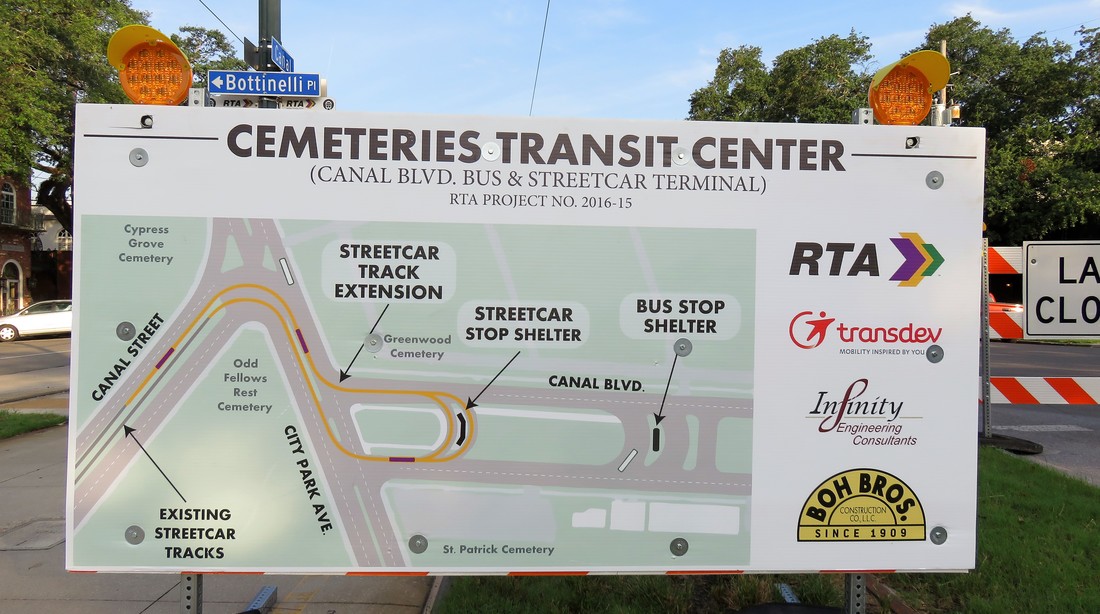

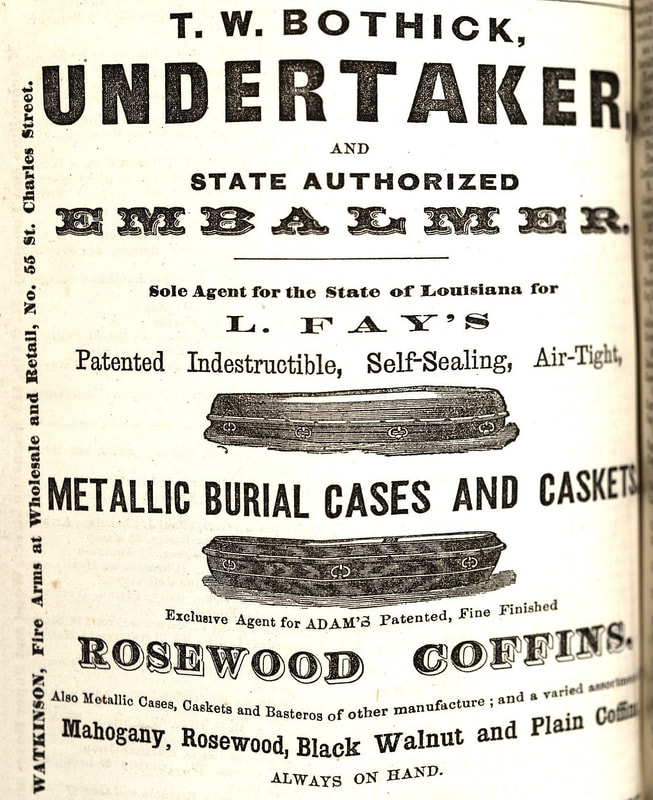

Additional incidents took place in Northern Irish cemeteries, including Belfast City Cemetery and Goldenbridge Cemetery, where the front gate was set on fire. Derry/Londonderry City Cemetery, which was noted in 2016 to have repeated vandalism incidents, did not report any incidents in 2017. In December 2017, two tour guides in Belfast began tours of the city’s cemeteries as a means of combatting vandalism. Other international cemetery vandalism events highlight local and regional political strife. In January, cemeteries in Poland and Ukraine were vandalized with Nazi graffiti and anti-Semitic slurs. Both instances were blamed by local press on Ukrainian nationalists. A Jewish cemetery in Lorraine, France, was vandalized in April in an incident that was seen as anti-Semitic. In Lausanne, Switzerland, the Muslim section of a public cemetery was vandalized with graffiti reading “Muslims out of Switzerland.” Responding to Cemetery Vandalism Cemetery vandalism can be seen as a barometer for political and social unrest. In 2016, we looked at this aspect of cemetery vandalism primarily from an international standpoint – examining vandalism in Ireland and Armenia. In 2017, cemetery vandalism reflected such concerns in the United States more than in the years previous. While this increase in targeted cemetery vandalism is very concerning, it must not be overlooked that heightened attention to cemetery vandalism has had an impact. Recovery from vandalism incidents is slightly more often reported and also includes focus on the communities that use and cherish a cemetery. In 2017, some cemeteries even published press releases asking community members to become involved and vigilant before cemetery vandalism occurs. Criminological theory states that cemeteries which appear cared for and visited tend to experience less vandalism. This understanding appears to have been utilized in vandalism responses in 2017. Closed circuit television, security, and other physical and intangible barriers to antisocial activity have also become more common. Prevention and community involvement are shown time and time again to be the best things to combat cemetery vandalism. Cemetery vandalism is inevitable, but can be mitigated and prevented to an extent. As we move forward into 2018, we hope to see the kind of police follow-through, community response, and enthusiastic recovery that was seen in 2017 despite the discouraging events that precipitated them. This is the fifth and final part in a five-part series on the historic landscape of City Park Avenue and Canal Street, and its associated cemeteries. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. To start at the beginning of this series, find Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here, and Part Four here. By the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue had undergone a century of extraordinary change. Where once Bayou Metairie meandered westward past acacia trees and a pastoral ridge, now City Park Avenue coasted across the New Basin Canal to become Metairie Road, past the grand monuments of Metairie Cemetery, and into Old Metairie. Where once the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove stood tall over an undeveloped landscape, now cars rumbled past the monuments and walls of Greenwood Cemetery and Odd Fellows Rest. Jazz blared from the Halfway House beside the New Basin Canal through the 1920s, until the House was converted into an ice cream parlor in 1930.[1] Bayou Metairie had slowly been filled in to accommodate City Park Avenue. To the east, Delgado Central Trades School (now Delgado Community College) was opened in 1921. Beside Delgado, Holt Cemetery remained the municipal potter’s field for New Orleans, but in 1940 the cemetery gained a new neighbor – the Higgins Boat Plant. PTs, Higgins, and the Cemetery Andrew Higgins (1886-1952) is known today in New Orleans as the man who brought the shallow-bottom PT and “landing craft, vehicles, personnel” or “LCVP” boats to the Allied effort in World War II. LCVP boats were used extensively in the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1945, leading then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower to say in 1964 that Higgins had “won the war for us.” Before World War II, Higgins had gotten his start designing shallow-bottom boats that performed well in the Louisiana bayous and other waterways beset by submerged obstacles. But by the late 1930s, Higgins produced new designs that not only could achieve amphibious landings in shallow waters, but were also equipped with ramps to allow swift disembarkation upon landing. These qualities made Higgins Boats imperative to the war effort. In 1940, Higgins Industries constructed a $1.5 million boat-building facility in the least expected of places: far from water, along City Park Avenue, and beside Holt Cemetery. Ever known for his enterprising spirit, Higgins’ City Park plant became the “world’s largest boat manufacturing plant housed under one roof.”[1] The plant took advantage of the Southern Railway line that cut northwesterly across City Park Avenue, beside Masonic Cemetery No. 2. Boats would be manufactured at the City Park plant, which employed thousands of people, and shipped to Lake Pontchartrain for testing. The booming wartime production of the plant left the operation bursting at the seams. Said historian Jerry Strahan of Higgins’ need to expand: “The back of the shipyard was adjacent to Holt Cemetery. Higgins decided to enlarge the plant ‘knowingly and willingly’ by preempting an unused portion of the cemetery grounds. The plant was increased until 40 percent of the new facility was constructed on property to which Higgins held no title, a problem that was unresolved as late as 1947.”[2] Photos of the plant and adjoining Holt Cemetery can be found here under photographs numbered 14 and 21. As early as November 1945, the loss of massive wartime governmental contracts hit the Higgins plant hard. The property was put up for sale.[3] The building at 501 City Park Avenue would have myriad uses over the next thirty-five years – it was a Piggly Wiggly grocery store in 1948, offices for Georgia Pacific Corporation in 1959, and part of the building was used as an art warehouse in 1964.[4] From the 1960s through the 1970s, a van and storage company conducted business in the old plant. In 1972, the building was demolished - its walls, beams, floors, and other items sold for salvage.[5] Finally, in 1982, Delgado Community College opened the Arthur J. O’Keefe Administration Building at 501 City Park Avenue.[6] The architecturally intriguing building remains in the same capacity to this day. In 1964, Holt Cemetery would cease to serve as New Orleans’ potter’s field. The city of New Orleans, under coroner Frank Minyard instead leased a lot from Resthaven Cemetery in New Orleans East for this purpose. This section of Resthaven continues to serve as New Orleans’ indigent burial ground. The American Way of Death After the close of World War II, industries which had boomed forward industrially and technologically looked inward for domestic uses of their innovations. Higgins Industries attempted to this very thing: selling Higgins-designed watercraft for private uses. While to contemporary readers it may seem strange, the same phenomenon took place in the funeral and cemetery industries. Moreover, the clientele of these industries had changed: they were more prosperous, more mobile, and had different values. For 1950s Americans, death was to be confronted with more discretion, privacy, and modernity than had been the case for previous generations. The cultural boom of the 1950s held an inherent disdain for the old-fashioned. This trend is often best exemplified in the scorn held for Victorian architecture during this period. Modern Americans sought urban renewal to wipe away old landscapes. In New Orleans, such sentiments manifested in the rapid construction of community mausoleums, establishment of “memorial park” style cemeteries like Garden of Memories, and the destruction of Girod Street Cemetery. Girod Street Cemetery was established in 1822 at the foot of Girod Street near Liberty Street. By the mid-1950s, the cemetery was bounded by the New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, part of a neighborhood seen as old, blighted, and an obstruction to progress. After repeated attempts by the cemetery’s owner, Christ Church Cathedral, to resurrect the cemetery both architecturally and functionally, it was expropriated by eminent domain to the federal government and the City of New Orleans. The cemetery was demolished in 1957. Girod Street Cemetery was located far from the Canal Street cemeteries, but it held certain cultural and architectural ties to other Protestant-dominated cemeteries like Cypress Grove and St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery. As the process of demolition began, the Huber family which had assumed ownership of St. John’s Cemetery in the 1920s, jockeyed for the contract to relocate the Girod Street remains. This competition involved multiple cemetery craftsmen-turned-cemetery owners and would not be the last time a cemetery operator competed for business with his peers. At the same time Girod Street Cemetery was being demolished, cemeteries at Canal Street and City Park Avenue were modernizing. The first inklings of cemetery stoneworkers turning to cemetery operation began in the 1910s and 1920s. For example, in 1910, stonecutter Albert Stewart assumed ownership of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street, acquiring it from the Suarez brothers. The Huber family had gained ownership of St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery in the 1920s – and by the 1930s, began construction on Hope Mausoleum, the first community mausoleum in New Orleans. Community mausoleums had gained some traction in the United States beginning in the 1890s and increasingly so in by the time of the Great Depression. In this era, the idea of a large, single-structure facility for burial appealed to cultural ideals of mutual benevolence (indeed, many belonged to fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows) and frugality. In New Orleans, these cultural desires were often met instead with society tombs – large, multi-vault structures within larger cemeteries. Society tombs were New Orleans’ version of community mausoleums, which reflected a more northern aesthetic. It is, then, not surprising that the Huber family gained ownership of German Lutheran St. John’s Cemetery and erected Hope Mausoleum around the historic burial ground. The development almost appears as an extension of St. John’s, Girod, and Cypress Grove Cemetery’s tendency to reflect non-Francophile aesthetics. In the early 1930s, Hope Mausoleum opened, a modestly Art Deco edifice encased in polished marble and touting itself as, “The Modern Way of Burial.”[8] The postwar boom of the 1950s saw a second heyday for community mausoleums, but these mausoleums suited newer cultural norms. The era valued opulence and modernity, sleek, state-of-the-art materials and a dearth of filigree and detail. The funeral and cemetery industries, rising into a new period of lobbying professional organizations, consolidated costs, and property accumulation, responded in kind. Indeed, author Jessica Mitford in her 1963 indictment of the industry, The American Way of Death, compared the contemporary funeral industry to the car industry of the same age: overloaded with space-age fins and baubles.[9] Thus, the new community mausoleum was meant to be an expression of modernity and opulence, and a doing-away with the stodgy funereal rituals and trappings of the past. Into this new market rose the children of Albert Stewart – Frank Sr. and Charles Stewart. Under their business, Acme Marble and Granite Company, the Stewarts purchased land adjoining the north boundary of Metairie Cemetery and set forth to construct a community mausoleum for the age. Completed in 1958, Lake Lawn Mausoleum would be the “the ultimate in modern burial,” with “paneling of rich mahoganies, carpeted floors, custom-built furniture, and rare plants and flowers.”[1] Lake Lawn would be the anti-Girod Street Cemetery. Historic photos suggest that Lake Lawn advertised within the walls of Girod Street, declaring that burials removed from the old Protestant cemetery could be moved to a thoroughly modern location. In fact, the engineer of Girod Street Cemetery’s demolition, Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, did just that. The contents of the Story family mausoleum, relatives of Mayor Morrison, were moved to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum in May of 1956. In the end, though, Hope Mausoleum would gain the contract to re-inter the white burials from Girod Street Cemetery. In accordance with contemporary segregation laws (even in death) Providence Memorial Park in Metairie would receive the African American burials from Girod Street. The torchbearer of urban renewal, Mayor Chep Morrison, would himself in death become part of the struggle between rising cemetery entrepreneurs, and the clash of new and old New Orleans cemetery culture. Shortly before his death in 1957, entrepreneurial monument man Albert Weiblen, who by this time had expanded his business to owning entire quarries in Georgia, purchased the entirety of Metairie Cemetery. His widow Norma maintained this enterprise after Albert’s passing, and when Mayor Chep Morrison perished in a tragic airplane accident in 1964, a standoff ensued between old Metairie Cemetery and modern, neighboring, Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Mayor Morrison had, as mentioned previously, moved his family’s remains from Girod Street Cemetery to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Yet while the new mausoleum was modern, Metairie Cemetery had been the lauded resting place of New Orleans mayors, governors, and Mardi Gras kings (nine, eleven, and more than fifty, respectively[1]). Metairie’s position in New Orleans culture was to be the hallowed resting place of power in all its forms. Presumably to preserve this reputation, Norma Weiblen called Morrison executor William H. Lindsay, Sr. on May 24, 1964, offering the Morrison family very steep discounts on a new tomb in Metairie Cemetery if they would consider moving Mayor Morrison’s burial there from Lake Lawn Park. She added that Lake Lawn Park was a “stinkpot,” and that she “knew [Metairie Cemetery] was where [Morrison] belonged.”[2] Years later, the matter would result in a lawsuit. Morrison was buried in Metairie Cemetery and, in 1969, Stewart Enteprises purchased Metairie Cemetery, renaming the joined properties “Lake Lawn-Metairie Cemetery.” The modernization of historic cemeteries at the end of Canal Street was fueled by the spirit of an era – and a struggle for space. By the 1950s, many of the cemeteries in the area were more than a century old. Furthermore, the city of New Orleans and the suburb of Metairie had grown tightly around them, leaving no room to expand. Community mausoleums were a practical way to capitalize on sellable space. Metairie Cemetery had made such a venture – filling in one of the cemetery’s lagoons to construct Metairie Mausoleum in 1958. In 1964, the various parish-owned Catholic cemeteries in New Orleans would be consolidated under the new New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. Ten years later, the Calvary at the rear of St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1 would be demolished to construct Calvary Mausoleum. In 1969, the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association would open Greenwood Mausoleum. The Jewish cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would also reorganize ownership. In the late 1950s, the Hebrew Burial Association would form to assume ownership of Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. With religious restrictions against above-ground burial, the cemetery instead appears to have expanded toward Bernadotte Street in this time, where today a section of modern, 1950s granite monuments stands. In 1973, conservative congregation Chevra Thilim established Chevra Thilim Memorial Park in a small triangle of land bounded by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, and Iberville Street. In 1999, Chevra Thilim merged with another congregation to form Shir Chadosh congregation, who retains ownership of the memorial park-style cemetery. Canals, Streetcars, and Automobiles Within cemetery walls, local stonecutters became sales agents and marble increasingly gave way to increased use of granite. No longer the city’s potter’s field, Holt Cemetery became a burial ground for the families of those already interred therein. Outside the cemeteries of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, water and soil gave way to concrete and pylons The New Basin Canal, in service since 1838 and arguably the heart of the cemeteries landscape, was by the 1950s no longer fit for industrial use. As with Bayou Metairie before, the canal was filled in and repurposed for automobile use. In 1958, a new overpass was constructed for City Park Avenue traffic to traverse over the canal, but its use would be short lived. By 1962, sections of the canal nearest to Lake Pontchartrain were filled in and became West End Boulevard. At the end of the wide boulevard’s neutral ground, a civil defense bunker was constructed as a station of command for government in the event of nuclear war. The bunker has been abandoned since the late 1990s, but remains present on West End Boulevard near Robert E. Lee Boulevard. Finally, in 1968, plans that had begun in the 1950s with Mayor Morrison came to fruition and a superhighway was constructed to connect Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Pontchartrain Expressway, part of Interstate 10, was constructed above the filled-in New Basin Canal – replacing high levies and deep water with tall pylons and dipping underpasses. Increased automobile traffic was met with increased automobile infrastructure, but one seemed to continually outpace the other. The roadways as they were in 1968 were complex and disconnected: Canal Boulevard met City Park Avenue, which met Canal Street in a dog-leg which already vexed motorists. The triangular lot of Odd Fellows Rest formed this dog-leg, and in the 1960s, civic eyes turned to eliminate the obstacle. The (sort-of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest As early as 1948, New Orleans’ City Planning Commission recognized the “dog-leg” problem.[13] As automobile drivers increasingly used Canal Boulevard and Canal Street as a commuter route to and from the city, the multiple turns needed to achieve this route caused traffic congestion. While the commission desired nothing more than to connect the two streets, Odd Fellows Rest cemetery had sat firmly between them since 1849. By 1963, the plan to “bypass” Odd Fellows Rest was revived. The Planning Commission announced in August of that year that it sought to purchase “the entire Odd Fellows Rest on the downtown river side of the intersection of Canal st. and City Park ave. and a very small portion of the adjoining St. Patrick No. 2 cemetery.”[14] The City would purchase the cemetery, relocate the remains interred therein, and demolish the remainder in order to connect Canal Street and Canal Boulevard. Like its neighboring cemeteries, Odd Fellows Rest had struggled to transition from the nineteenth century to the postwar era. In 1950, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) hired stonecutter Armand Rodehorst, Sr. as the new superintendant of the cemetery.[15] Rodehorst had worked for fifteen years across the street at Greenwood Cemetery, as a laborer for Samuel Gately. In joining Odd Fellows Rest, he was striking out on his own.[16] Rodehorst developed Odd Fellows much in the same way that other cemeteries had done. He built multi-vault tombs to sell piecemeal and constructed modern, cast-concrete tombs. In 1958, however, Rodehorst died in his home at the age of 56.[17] The economic future of Odd Fellows Rest was left without a helmsman. Thus, by 1963, the Louisiana Grand Lodge was positioned to sell the cemetery property, although “not interested in partial relocation, but in total relocation of the cemetery.”[18] City Council, Mayor Victor Schiro, and the Planning Commission agreed to fund the project. Property on City Park Avenue near Delgado Community College was selected, which the City would purchase and gift to the Odd Fellows for transfer of the cemetery’s remains. City Council purchased a lot “bounded by City Park Avenue, Conti Street, Virginia Street, and St. Louis Street” for the purpose.[19] Yet in a twist of fate perhaps unique to New Orleans and its local politics, a private firm learned of the land purchase and beat the City to the punch. The purchaser, Plaza Towers, Inc., bought the property and, in turn, offered to gift it to the City in exchange for another parcel of municipal land located on Howard Avenue and South Rampart. Unlike the City Park Avenue property, which was purchased only as leverage, the Plaza Towers firm needed the Howard Avenue property in their construction project: the forty-five story Plaza Tower building designed by Leonard R. Spangenberg, Jr. & Associates. This obvious power grab left City Council “irate.”[20]

In August of 2005, flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina effected even the cemeteries of Metairie Ridge. Metairie Cemetery lost its administrative building near the cemetery entrance, and untold tombs were damaged. In 2008, state-owned Charity Hospital Cemetery was converted into a memorial to the lives lost in Hurricane Katrina. The property was excavated and analyzed by archaeologists, and large vaults were erected, clad in reflective black granite. The unidentified and unclaimed remains of 86 hurricane victims were interred at this site, which each year is visited and dedicated on the anniversary of Katrina’s landfall. To learn more about the inspiring, harrowing, and touching story of the Katrina Memorial, please read this fantastic piece by Mary LaCoste in the Louisiana Weekly: “Remembering the Katrina Memorial that Almost Wasn’t.” The Last Days of the Halfway House The Halfway House, once positioned tranquilly along the New Basin Canal but by 2005 instead wedged beside the Interstate 10 overpass, was also damaged in the storm. Beginning in the 1840s as a place of rest and refreshment for carriages en route to Lake Pontchartrain, later a restaurant and jazz hall, then an ice cream parlor, the building was purchased in the 1950s by Orkin Pest Control Company. Abandoned by Orkin in the mid-1990s, by 2005 the property was derelict, its roof partially collapsed. The Halfway House was the property of the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association, held by a long-term lease by the city of New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina, plans were set in motion to convert the adjoining property – once Albert Weiblen’s marble shop – into the new 911 Communications Center for the city. It looked as if the Halfway House would be demolished to make way for a parking lot. Even before 2005, an organization called the Jazz Restoration Society worked with the FCBA and City to secure ownership of the Halfway House, with the goal of restoring it to a restaurant and music hall. Years of infighting, pushing and pulling, and negotiations in the city finally ended in 2009, when the building was declared a landmark and the Society was given permission to step in. But, much like the land deal between the City and Odd Fellows Rest, another shoe had to drop. When an environmental assessment was conducted at the Halfway House, soil tests found that forty years of pesticide storage and disposal left the property unsalvageable by even the best intentions. Despite years of fighting to save the Halfway House, it was demolished in 2010. Conclusion As of this writing, the current road construction project at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is on-schedule and should be finished in one week. Streetcar lines are laid, sweeping across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard. Archaeological assessments and relocation of remains from the cemetery beneath Canal Boulevard have taken place. Soon, the intersection will assume its most recent form, in a place that has held so many forms for one hundred and eighty years. In this series, we have seen this place conform to cultural changes, urban expansion, technological innovation, war, and peace. It is a testament to how imperceptibly dynamic New Orleans cemeteries are – that we can walk through them and feel tranquility and stillness, when in reality they’re shifting, conforming, losing and gaining things that will be held precious by future generations. And there’s even so much we’ve left out! Left out was the Perseverance Lodge No. 13 society tomb in Cypress Grove, hit by lightning twice in the late twentieth century and recently reconstructed by FCBA. Left out was the flower shop on Canal Street beside Cypress Grove, once a hub for chrysanthemums and roses shuttled off to the cemeteries, by the 1990s derelict, and demolished in 2016. The merger of Stewart Enterprises, Inc. with Service Corporation International in 2014 merits its own thousand words on the industrialization of funeral and cemetery industries. Uncountable changes have taken place in this tiny colony of cities of the dead. This retrospect, more than anything, then, has been an overture to recognizing how very important those aspects of our cemeteries which have survived all of this. From Cypress Grove to Chevra Thilim Memorial Park, from Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum to Holt Cemetery, it is impossible to appreciate these relics too much. [1] Samuel Charters, A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 257.

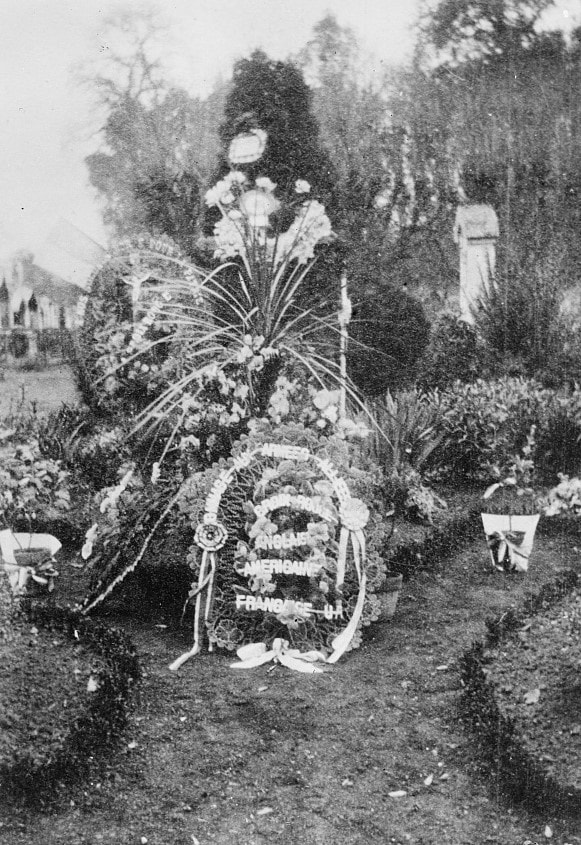

[2] Jerry Strahan, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats that Won World War II (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1994), 49-50. [3] Ibid. [4] “For Sale: Two of the Modern Higgins Industrial Plants and Clinic in New Orleans,” Times-Picayune, November 19, 1945, 17. [5] Times-Picayune, April 11, 19; Times-Picayune, October 6, 1959, 27; Times-Picayune, April 5, 1964, 71; Times-Picayune, February 10, 1964, 45. [6] “Higgins Shipyard,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1972, 44. [7] “Congratulations Delgado,” Times-Picayune, March 4, 1982, 19. [8] “The Modern Way of Burial” was Hope Mausoleum’s official slogan from the 1930s through the 1950s. For example, “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, May 2, 1935, 2; and “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, January 26, 1958, 2. [9] Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 20-21. [10] “Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, October 3, 1954, 15; “Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum – A Report on Progress,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1951, 10. [11] Henri A. Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, Inc., 1981), 108. [12] “Details on Switch of Morrison’s Burial Site Revealed,” Times-Picayune, May 5, 1966. [13] “End to Canal ‘Dog-Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1. I would like to recognize and thank Michael Duplantier for sharing resources and information contained in the (sort of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest section. [14] Ibid. [15] “Odd Fellows Cemetery,” Times-Picayune, December 26, 1950, 41. [16] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1935, Vol. LXI (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1935), 1171; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1938 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1938), 933; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1949 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1949), 1209. [17] “Business, Civic Leader Expires: Rodehorst Rites will be Held Today,” Times-Picayune, September 16, 1958. [18] “Accord on Canal Street ‘Dog Leg’ Plans Possible,” Times-Picayune, November 7, 1963, Section 2, 6; “Lodge to Help on Street Link,” Times-Picayune, August 20, 1963, 7. [19] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [20] “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, June 3, 1964, 1. [21] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [22] Edward J. Branley, New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line (Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 95. Today is All Saints’ Day! In New Orleans, the holiday is spent decorating the graves of loved ones in cemeteries. For some, small repairs and cleaning will be undertaken. Others will bring their children and picnic beside family tombs. Because New Orleans All Saints’ Day tradition is as old as the city itself, we like to reminisce on All Saints’ Days of yesteryear. We’ve looked at All Saints’ Day 1853, 1865, 1878, 1918, and 1945 in the past. This year, we’re time-travelling exactly one century, to November 1, 1917. The text below is from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, November 2, 1917. Some of the text is improperly microfilmed and thus illegible, but we find the reflections of the day to be compelling nonetheless: GRAVES OF DEAD FLOWER COVERED ALL SAINTS’ DAY Cemeteries Thronged with Relatives and Friends of Loved Ones Departed On certain occasions the Latin character of New Orleans comes to the foreground with particular clarity, and vivid examples are given of the French, Spanish, and Roman love of ceremony and custom. The Anglo-Saxon element seems also to have caught the [illeg] by association of culture, for the entire city appeared to have come out for the Feast of All Saints and to pay tribute to the brevity of the world. And it was done in New Orleans own individual way.

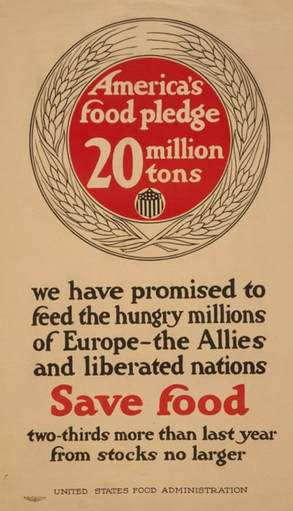

At the gates of Metairie, Greenwood, St. Patrick’s and the Masonic Cemetery sat nuns accompanied by children in the dull blue uniform of asylums who rattled a few coins in tin plates as a reminder of a more pressing duty to the dead than bringing flowers, and repeated in sing-song the plaintive plea: “Help the orphans, mister.” Around some tombs whole families seemed to have congregated for the day; there were chairs and lunch baskets and pillows for the younger members to take siestas during the afternoon. With balloon men, peanut men, vendors of flags, soft drinks and popcorn a most festive atmosphere prevailed among the stream of automobiles that passed continually. Truck loads of picknickers were frequent. Registration booths for the signing of the food pledge had been opened at the larger cemeteries and zealous officials hailed every woman who entered with the query: “Have you signed?” They were met with a variety of replies. Many only smiled and nodded, but occasionally a haughty lady would toss her head in scorn and come back with: “No, and I don’t intend to!” or some mother, harassed by a flock of wailing offspring would answer with a flood of Italian that lost none of its fire by being unintelligible. St. Roch’s Cemetery has a quaint charm all its own on All Saints. The tombs are different, the decorations of shells and wax flowers and embroidered mottoes are different, and there is nothing else in the world quite like the tiny chapel with the crutches, canes and artificial arms and legs laid around the altar as a thank offering to good St. Roch, the healer of infirmities. Special tables are erected for the occasion to hold the candles of those who have made a wish for the saint to fulfill during the next twelve months.

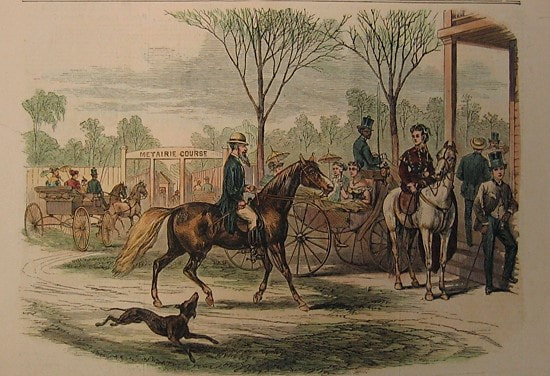

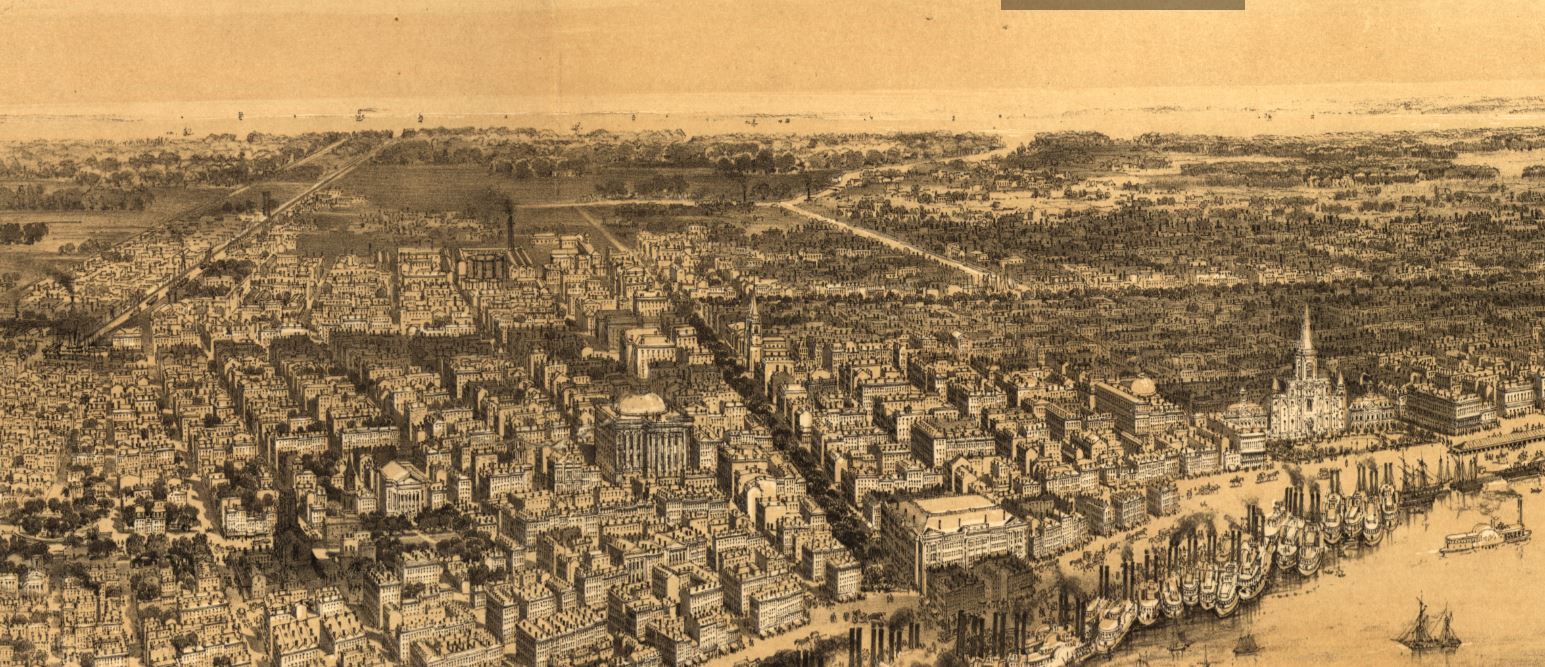

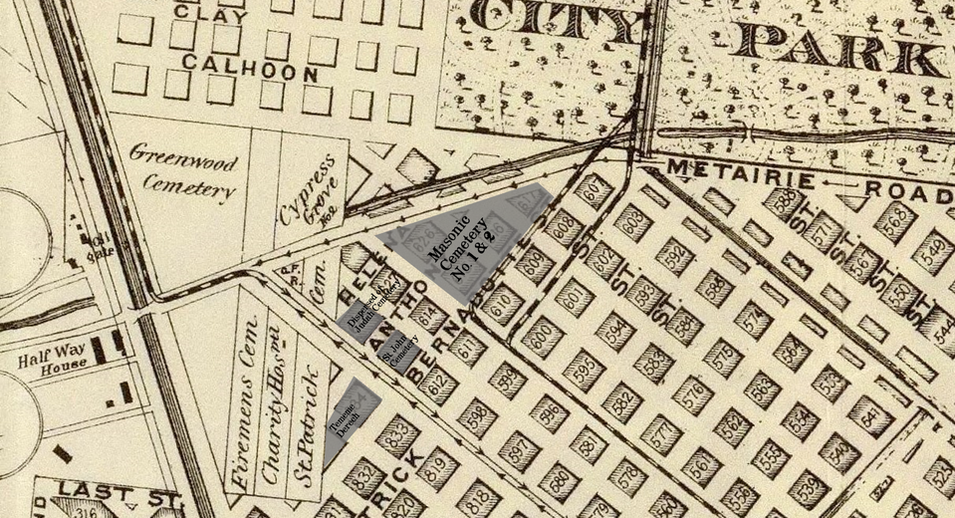

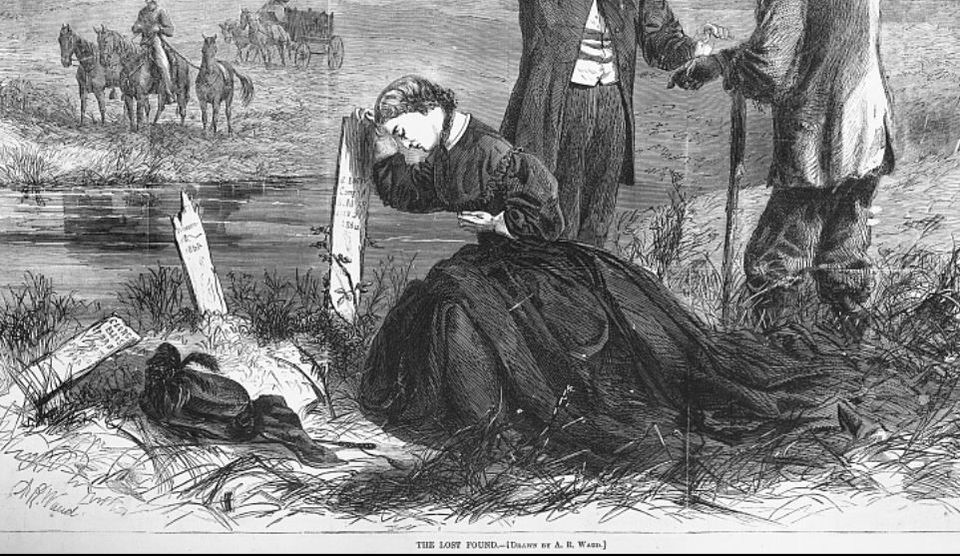

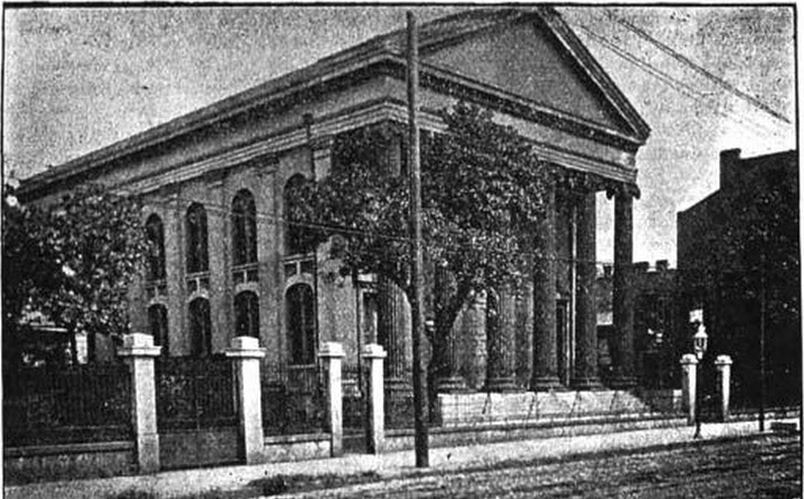

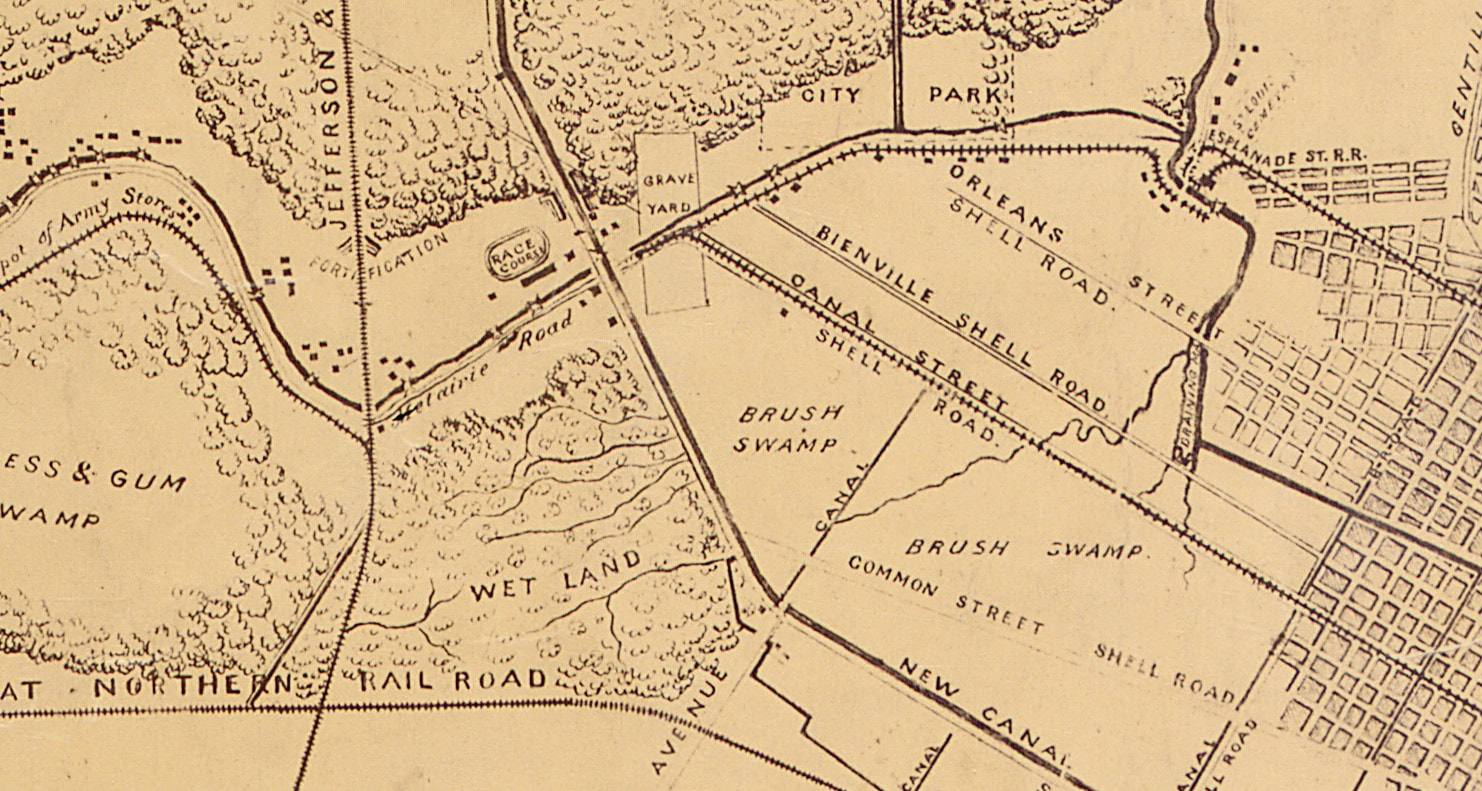

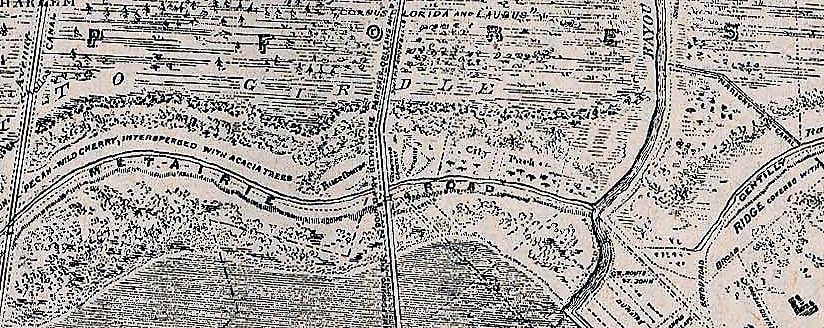

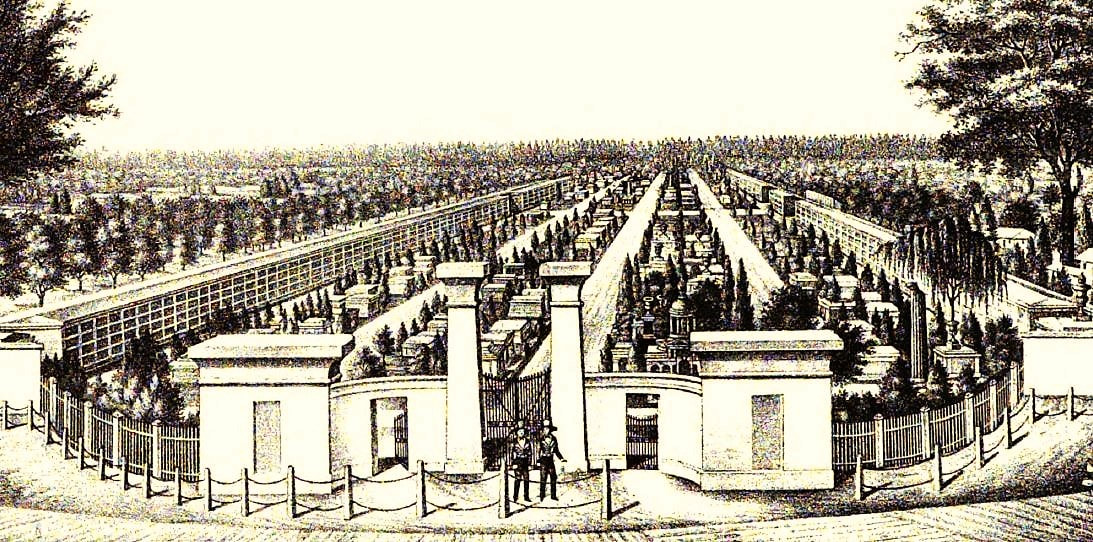

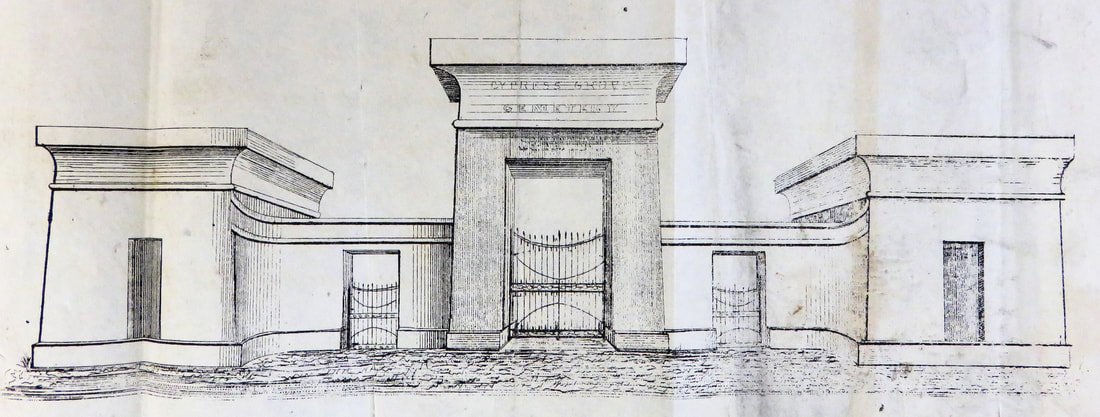

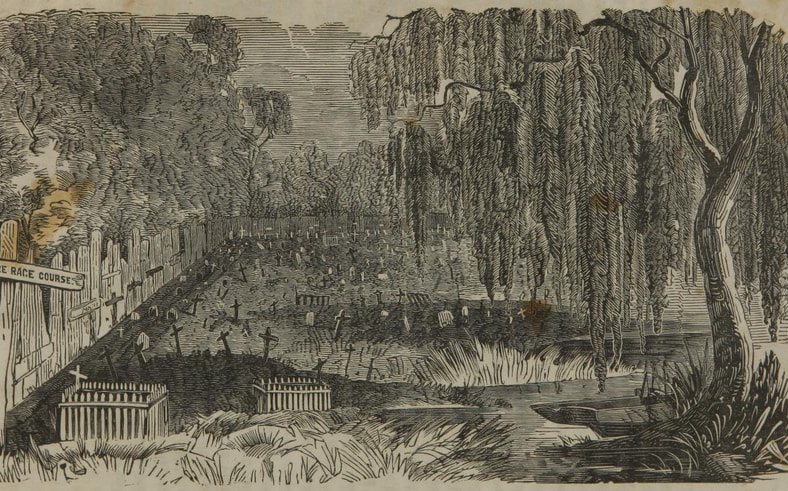

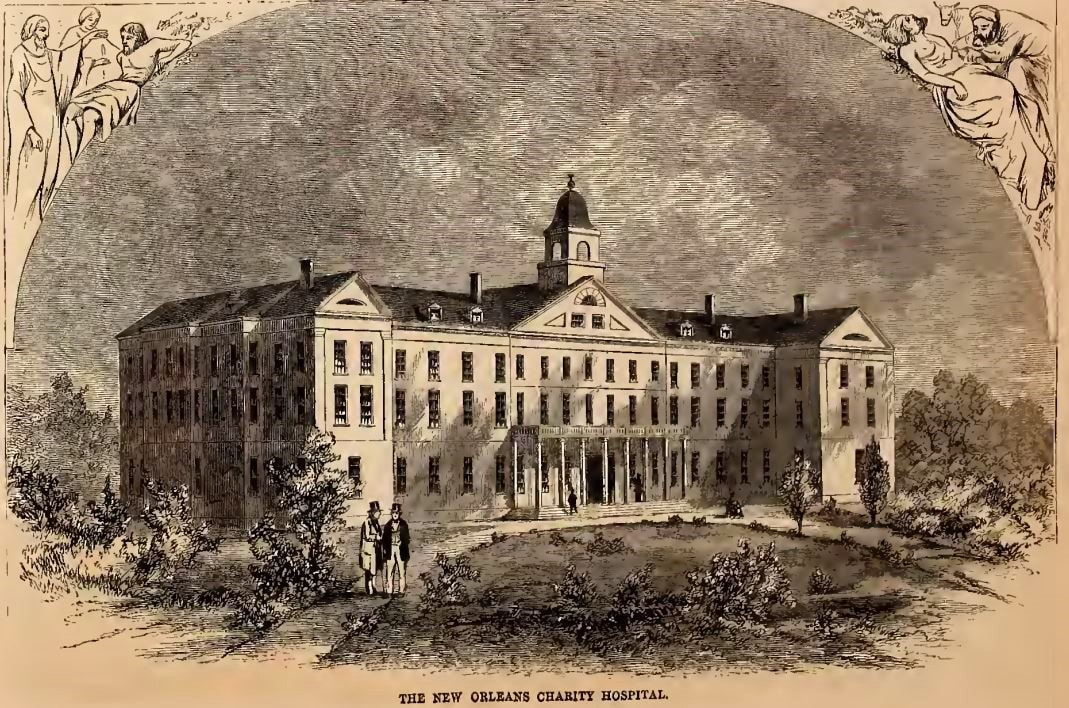

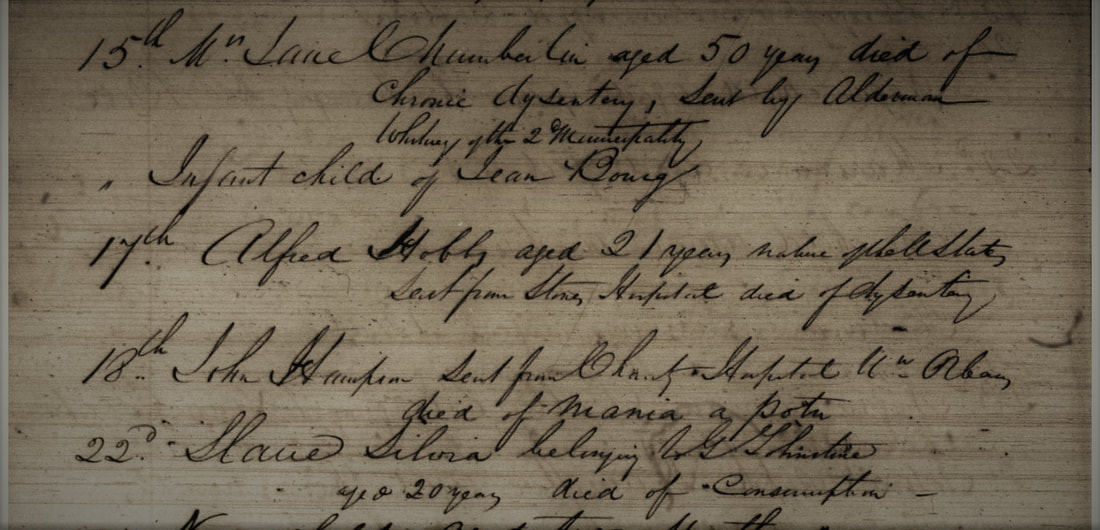

This is Part Four in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here, Part Two here, and Part Three here. To say that New Orleans changed drastically after the Civil War is an understatement. The economic engine of the city, which formerly relied on the institution of slavery, subsequently shifted. The city increased in population and expanded in demographics. Transportation was in the process of revolution. For the cemeteries, this period meant the industrialization of funerary craft. New materials and architectural styles appeared in cemetery landscapes, and a new kind of cemetery stonecutter would evolve. By 1930, the quiet intersection at Metairie Ridge would be transformed. Railroads, automobiles, repurposed land, and the complete disappearance of one cemetery took their effect on the landscape. The most notable monuments of Greenwood Cemetery would be erected atop a filled-in Bayou Metairie, while other sections of the bayou were converted into reflecting lagoons. But before all of this took place, the founding Metairie Cemetery would change how New Orleaneans understood their cemeteries. 1873: Metairie Cemetery Metairie Race Course had operated on the other side of the New Basin Canal from Greenwood Cemetery since the 1830s. Bounded by Bayou Metairie to the south, the race course had capitalized on the Crescent City’s appetite for sport and diversion. Yet the sport of horse racing was economically dependent on the institution of slavery: enslaved people trained racehorses, rode them as jockeys, and were even utilized as chattel in racing wagers. After the Civil War and emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the South, as well as the economic collapse heralded by the war itself, horse racing was no longer a lucrative pastime. The race course declined.[1] The end of the Civil War also enhanced cultural understandings of death nationwide. Victorian culture transformed the budding rural cemetery movement into a much larger “beautification of death” period. Cemeteries became public parks fit for day trips and picnicking. Civic notions of memorialization and mourning had brought forth new zeal for monuments and landscapes to frame them. At the same time, the craft of stonecutting and tomb building was beginning a revolution that would eventually lead to industrialization, new materials, and innovative techniques that could produce larger, more ornate tombs and monuments with less labor. All of these influences likely led to the transformation of Metairie Race Course to Metairie Cemetery in 1873. Conversely, colorful local legend often attributes the founding of Metairie Cemetery instead to the jilting of its founder, Charles T. Howard, by the Metairie Jockey Club. After repeatedly being denied membership, Howard is said to have declared he would buy the property and “make it the deadest place in town.” Yet the economic and cultural realities described above were much more likely to influence the cemetery’s founding: horseracing was no longer economically feasible, and garden cemeteries had become nationally popular. The founding of Metairie Cemetery would likely have been a matter of economic practicality. Furthermore, the founders had but to look across the New Basin Canal to the ten cemeteries nearby for inspiration.[2] Metairie Race Course declared bankruptcy in the early 1870s. In May of 1872, the Metairie Cemetery Association was formed with William S. Pike as president and Charles Howard, D.F. Kenner, W.S. Lipscomb, G.A. Breaux, and J.A. Morris on the Association’s board. By mid-1873, the Association had secured ownership of the land in perpetuity and without taxation by way of an act of the Louisiana legislature; this act also empowered the Association to punish trespassers who harmed tombs, shrubbery, or shot guns in the cemetery.[3] The Association chose architect Benjamin Morgan Harrod to design Metairie Cemetery. By this time, rural garden cemeteries were an institution of the American landscape. New Orleans had welcomed its first rural cemetery in 1840 with Cypress Grove; yet while the old Fireman’s Cemetery incorporated landscaping and horticultural features like its northern sisters, it lacked the ambling roadways and water features that so distinguished rural cemeteries like Mount Auburn, Green-wood and Laurel Hill. Under Harrod’s influence, Metairie Cemetery would emulate the northern rural cemeteries even more than Cypress Grove had. Thousands of trees were planted along the racetrack’s original thoroughfare. New roads were placed within and outside the racetrack itself, but kept with its oblong shape. Metairie Cemetery was also the first cemetery in New Orleans to be owned by a private association. To this point, all cemeteries were owned by either religious organizations (churches, synagogues), fraternal organizations (firemen, Masons, Odd Fellows), or the City of New Orleans. Charity Hospital Cemetery was owned by the state. The concept of the cemetery as a private enterprise had long been familiar outside of New Orleans, and the model of private cemetery ownership would expand in the area as time progressed.[4] Metairie Cemetery quickly became a new venue for leisure travel on the New Shell Road. The concept of the cemetery as a public park, which had been popularized by northern rural cemeteries, would take hold in earnest at Metairie. Carriage rides through the cemetery became part of a day trip to the West End or to the Halfway House. The cemetery was bordered on two sides by water – with Bayou Metairie to the south and the New Basin Canal to the east. As the cemetery was populated with high-style tombs, military tumuli, and grand society tombs, the recreational draw only increased. The founding of Metairie Cemetery was in itself the result of Reconstruction-era economic shifts. The cemetery later would fill with tombs and monuments reminiscent of the era. Confederate burial societies would erect grand tumuli in Metairie Cemetery; those who made their fortunes and gained political power in Reconstruction-era New Orleans would find their last rest there. In 1879, however, another cemetery would iterate an entirely different aspect of the period within its picket-fence boundaries. Less than a mile down Bayou Metairie, Holt Cemetery would be established. 1879: Holt Cemetery The cemeteries of Metairie Ridge each served a specific community: Cypress Grove served mostly northern-born Protestants, Odd Fellows Rest buried Odd Fellows, and so on. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 and Charity Hospital Cemetery both served indigent dead and “strangers” (travelers or the newly-arrived). They were not by any means the only two cemeteries to serve as “potter’s fields.” In the nineteenth century, Protestant Girod Street cemetery held a section for indigent or epidemic burials; the city-owned cemeteries of Lafayette, Jefferson, and Carrollton also buried the indigent “at the expense of the city.[5]” Two additional cemeteries were operated by the City of New Orleans specifically as potter’s fields. They were Locust Grove No. 1 and No. 2. Located near LaSalle Street, at the center of what is now the Harmony Oaks housing complex, Locust Grove No. 1 was opened in 1859, with No. 2 opening in 1877. These cemeteries were located in the “back of town” near the St. Joseph Cemeteries and Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. This area was especially flood-prone, which vexed city health officials and caused much complaint about the condition of the Locust Grove Cemeteries. Furthermore, the city Board of Health often fretted about the transport of remains to this area, which was remote at the time. The state of public health in New Orleans was a topic of much debate in the 1870s. Many administrators of the Civil War Union occupation were proponents of the sanitary movement which valued clean streets, drainage, and sewage as public health concerns – a novel concept at the time. So it was that during Federal occupation special attention was paid to issues like standing water, disposal of slaughterhouse waste, and fresh air. The success of these policies is often measured in the fact that no epidemics took place during the occupation. The cause and effect are debated, but the result was the same. Some sanitarian notions persisted after the Civil War. The Slaughterhouse Case, a public health ordinance that became a landmark Supreme Court ruling, was one result of this new philosophy. However, care to restrict standing water and the breeding of mosquitoes slackened after 1865, and New Orleans saw a yellow fever epidemic in 1867. Eleven years later, the city would experience the worst yellow fever epidemic since 1853. As many as ten thousand people died in the New Orleans epidemic of 1878. The volume of indigent burials at Locust Grove Cemetery in 1878 was enough to exacerbate the cemetery’s already-poor reputation. The president of the Louisiana Board of Health at the time, Dr. Joseph Holt, a sanitarian in his own right, lambasted the condition of the cemetery.[6] In 1879, Locust Grove Cemetery No. 1 and 2 were closed and the City of New Orleans bought a small lot of land near City Park for a new municipal potter’s field. The cemetery was seen as an improvement for a number of reasons. Primarily, it was located on the raised land of Metairie Ridge, making in-ground burial more feasible. Board of Health records also show that the cemetery location was desirable for transportation purposes: remains could be transported down the “various shell roads” (the New Shell Road and the Bienville Shell Road) to the cemetery without too much exposure to primary thoroughfares. Finally, the cemetery was considered remote enough to minimize the chances of the cemetery itself breeding contagion or creating infectious “miasmas,” a concept that persisted into the late nineteenth century.[7] The cemetery was named after Dr. Joseph Holt (1838-1922), a nod to his pioneering studies in epidemiology and quarantine. It was not the first cemetery to be named after a person in New Orleans (McDonoghville Cemetery in Algiers has that claim), but it is certainly the only cemetery named after a person still living. Dr. Holt himself would be aware of his own namesake for forty-three years until his own death. Dr. Holt was buried in Greenwood Cemetery. In 1909, Holt Cemetery would be expanded toward St. Louis Street, nearly doubling its size. Enclosed with a simple picket fence and dominated by wooden markers, Holt succeeded Locust Grove as a cemetery utilized by African Americans, although not exclusively so. Over time, this cultural tie would make Holt Cemetery a place for the practice of African American burial traditions and a venue for folk memorial art. Although the cemetery ceased to be the municipal potter’s field in the 1960s, it remains in use by property owners to this day.[8]

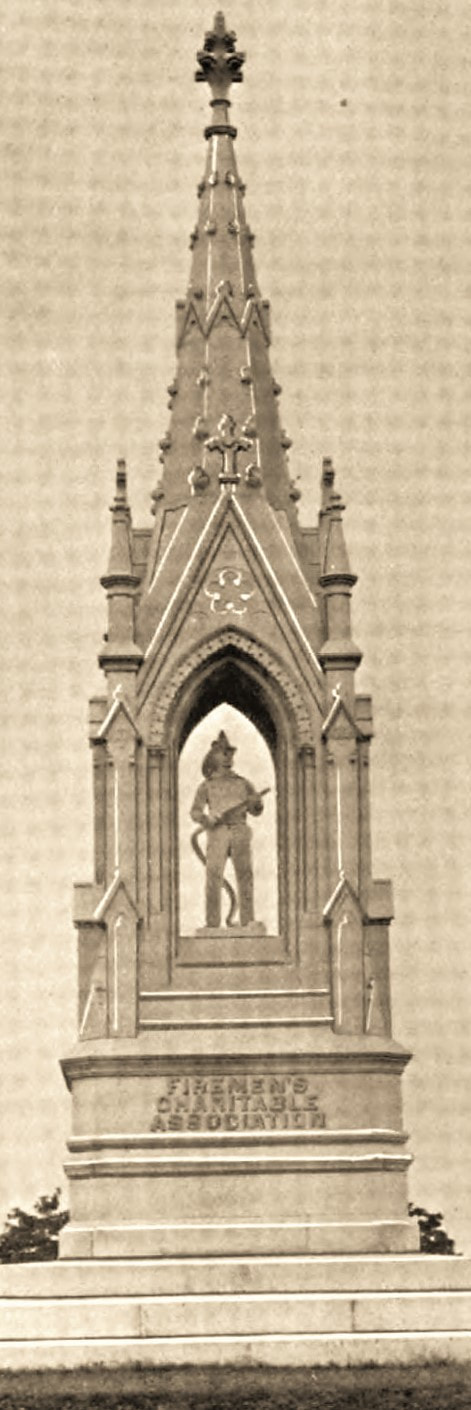

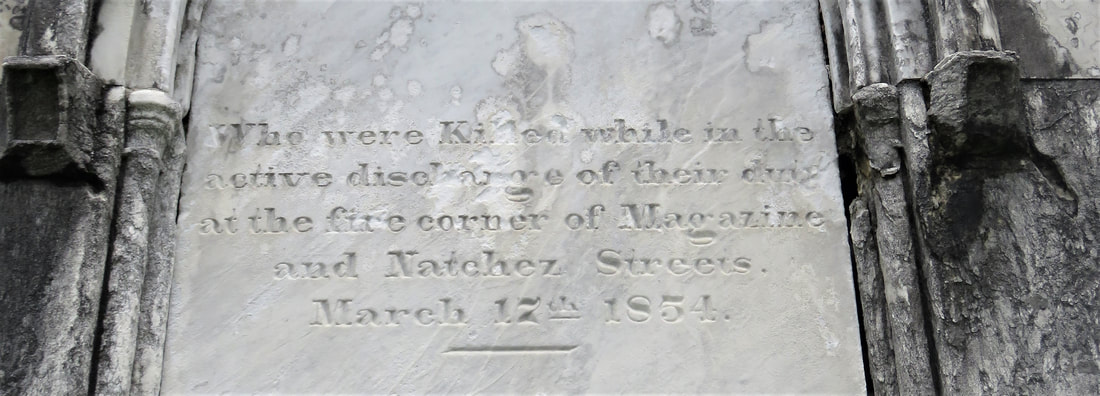

Greenwood had also acted as an extension of its sister cemetery, Cypress Grove, which was also owned by the Firemen’s Charitable Association (FCA). Much like Cypress Grove, the tumulus was a common burial style in Greenwood Cemetery. But for those who look upon Greenwood Cemetery today from the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Greenwood would have been hardly recognizable in the early 1870s. As the bayou ran in front of the cemetery, none of the great monuments that the cemetery is known for had yet been built. This changed in 1874 with the Greenwood Cemetery Confederate monument. As mentioned in Part Three, the Ladies Benevolent Association purchased land at the front of Greenwood Cemetery, beside the Woodruff and Mcleod Monument. A monument was constructed there, designed by Benjamin Harrod of Metairie renown, and constructed by George Stroud, a stonecutter who worked prolifically in Greenwood and Cypress Grove cemeteries. At least one of the four busts mounted to the monument was carved by famed New Orleans sculptor Achille Perelli.[10] The Ladies Benevolent Association Confederate monument marks the mass grave of at least six hundred unidentified soldiers. It was the first of its kind in New Orleans, although the Washington Artillery, Army of Tennessee, Army of Northern Virginia, and the Soldier’s Home would establish similar burial sites for Confederate veterans. The Greenwood monument is the only one of its kind to exclusively memorialize those who died in action and without identification. Far on the southwestern boundary of Greenwood Cemetery and overlooking the New Basin Canal, the Confederate burial site would be among the tallest monuments in the landscape for a little over a decade. In 1887, however, the firemen of New Orleans who had owned and cultivated the cemetery for three decades would finally construct their own grand memorial. The FCA celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 1885. The organization represented the volunteer firemen of New Orleans in both a professional and social capacity, and it functioned as New Orleans’ primary fire response. Dozens of fire companies dotted the city’s landscape, each company serving its neighborhood’s firefighting needs, and most companies provided burial in society tombs. The FCA also provided financial support for widows and orphans of firemen. For fifty years, the FCA had been the organization through which all fire companies functioned.[11]

Twenty years after the Hennessey monument, Albert Weiblen had capitalized on technological and infrastructure developments in the monument industry to such an extent that he purchase an entire Georgia marble quarry in 1911. In this same year, Weiblen was contracted to build the Elk’s Lodge tumulus in Greenwood Cemetery. The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (BPOE) has been present in New Orleans since the nineteenth century. Like many benevolent and fraternal organizations, the New Orleans Elks Lodge No. 30 sought a collective burial place to serve their members. While their aim to construct a society tomb was not unique, the Elks pursued their goal in a few unorthodox ways. For instance, the Elks raised the funds to construct the tomb by hosting a “burlesque circus” complete with elephants, acrobats, and a petting zoo of baby elks over Mardi Gras 1911. Elks members costumed as clowns and even travelled abroad to learn how to care for circus animals. Said one newspaper of the spectacle: “Quite a number of the antlered herd are taking corresponding lessons on how to manage elephants and camels.[13]” For Greenwood Cemetery and Albert Weiblen, however, the Elks defied a different kind of orthodoxy with their new tomb. The Elks lodge tomb would be a tumulus structure built at the very front of the cemetery, beside the Firemen’s monument. It is said that the Greenwood Cemetery property purchased by the Elks for this purpose is situated on the former bank of Bayou Metairie, which was in the process of being filled in by 1911. Weiblen, who would build dozens of remarkable tombs over the course of his career, as well as having a hand in the Stone Mountain monument in Georgia, contested the soggy location as incapable of supporting the tomb’s foundation. Yet the Elk’s Lodge tumulus was constructed despite these objections. Over time, some minor foundational issues have caused the tumulus to tilt toward Canal Street. The monumental mound remains a presiding element of the landscape today, with its bronze elk looking out over the intersection. Segregation in the Canal Street Cemeteries The period between 1873 and 1930 was also marked by Reconstruction and the later institution of Jim Crow laws – a period that began with the New Orleans Separate Cars Act in 1890, leading to Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. For the Canal Street cemeteries and New Orleans cemeteries as a whole, the institution of “separate but equal” services extended to memorialization and burial. Before the Civil War, many of the Canal Street cemeteries were de facto segregated – while burial of African Americans was not explicitly prohibited, such burials simply did not take place. The divide was mostly due to the fact that some cemeteries served primarily white religious communities such as German Lutherans or Irish Catholics. Cypress Grove Cemetery and Greenwood Cemetery were noted in 1881 as each having a section “set apart for colored persons.”[14] Jim Crow nonetheless made its mark on the Canal Street Cemeteries. While Holt Cemetery was not officially racially segregated, it remained the only cemetery in the area to primarily perform burial for African Americans. In some cases, the influence of racial restriction in cemeteries was more stark. In the winter of 1912, a recent burial in Odd Fellows Rest was found by the cemetery sexton to be that of an African American woman. Upon this discovery, the sexton exhumed the elderly woman’s grave and “dragged the casket containing the corpse out of the bounds of the cemetery. It was then conveyed to Cypress Grove.[15]” The incident called into question the understanding of segregation in cemeteries. The owner of the Odd Fellows plot, Mrs. Bowling S. Leathers, had purchased the lot that year for herself, her husband, and her “faithful old negro mammy.” However, the administration of Odd Fellows Rest insisted that the cemetery was for “white people of good character” only, and that Mrs. Leathers had misled the cemetery sexton as to the identity of the interred. The scant documentation of this incident highlights a conundrum for cemeteries that to this point were de facto segregated. The Times-Picayune reports that prior to the burial of Mrs. Leathers’ companion, cemetery sextons would only receive burial certificates from the city board of health after the interments were complete. As burial certificates would be the only official documentation noting the race of the deceased, these records suggest that in most cemeteries, enforcement of segregation would have been performed on a type of honor system, lest more disinterments take place. Mrs. Leathers sued the Odd Fellows for the incident, although the outcome of the suit is unclear. Ten years after the Odd Fellows controversy, Metairie Cemetery met its own segregation controversy. Long the designated burial ground of New Orleans’ political elite, in 1922 former Governor of Louisiana Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback was to be buried on its grounds.

Metairie Road, which paralleled Bayou Metairie, was expanded and would come to accommodate automobile traffic. Possibly in a response to the new traffic patterns, the entrance to Odd Fellows Rest was moved from Canal Street to the corner of Canal and what would become City Park Avenue. A large overarching parapet and awning was built at this corner of the cemetery – a project that necessitated removing a number of burial vaults. Beginning in the 1880s, the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association would advertise intermittently in newspapers that those with loved ones buried in Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (also known as Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2) should remove their kindred’s remains from the property. It is unclear when Cypress Grove No. 2 was officially closed, although it has been suggested that the cemetery had been inactive since the 1860s. By the 1920s, no monuments or traces of the cemetery remained. The property became a landfill.[16] The enterprising spirit of Albert Weiblen would make him an unparalleled success in New Orleans cemeteries. But Weiblen wasn’t alone in his path from local craft stonecutter to intrepid industrialist. By the 1920s, stonecutter Victor Huber was following a similar trajectory. In 1926, he opened his own showroom and workshop at 5055 Canal Street, beside Odd Fellows Rest. Like Weiblen, Huber would go on to orchestrate enormous changes in cemetery management and industry. Stonecutters like the Stewart brothers, who owned Acme Marble and Granite Company, and the Alfortish family, were also beginning to expand their aspirations in the cemeteries. The Halfway House, which had sat at the intersection of Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal since the 1840s, remained a place of diversion for day-trippers between the city and Lake Pontchartrain. By the 1920s, this clientele included riders of a streetcar that extended to the West End as well as automobile drivers along Metairie Road and the Shell Road. In this time, the Halfway House experienced a sort of renaissance. Jazz clubs in suburban neighborhoods saw their heyday in the 1920s, and the Halfway House, though sparsely furnished, was the home of the Halfway House Orchestra led by cornetist Albert “Abbie” Brunies. Multiple recordings of the Halfway House Orchestra are available even today, and the band is seen as a seminal element of 1920s New Orleans jazz.[17] From the 1860s to the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue progressed from a quiet intersection of waterways and cemeteries to a burgeoning place of cemetery commerce, modern culture, and expanded architecture. By 1930, the beginnings of the traffic-choked cemetery intersections had come into view. The rest of the twentieth century would see even greater changes both within and outside of the cemetery walls. [1] Nikki Williams, “Racing and Slavery in Antebellum Louisiana, 1840-1865,” Louisiana Historical Association Conference, March 17, 2017, Shreveport, Louisiana.