|

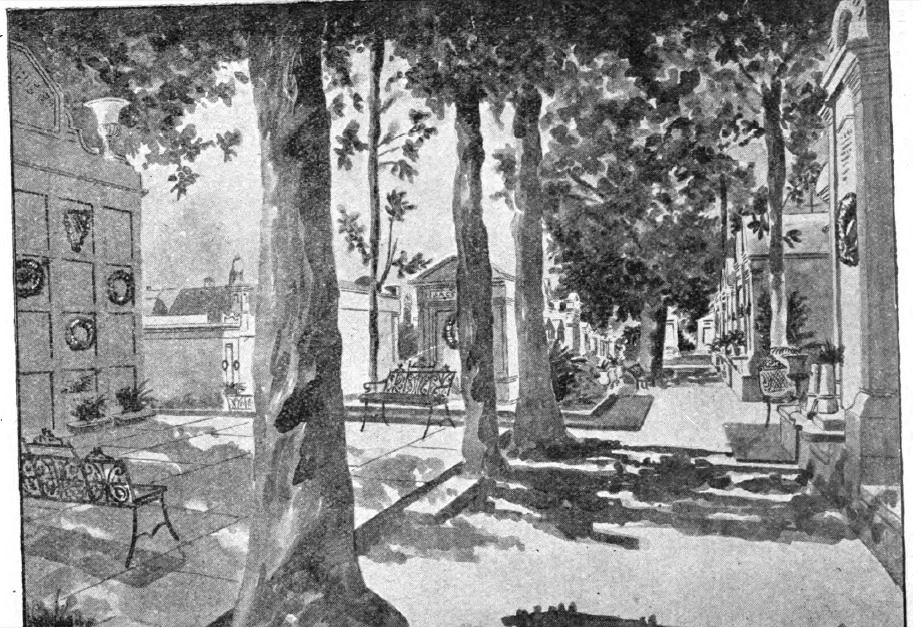

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb.

2 Comments

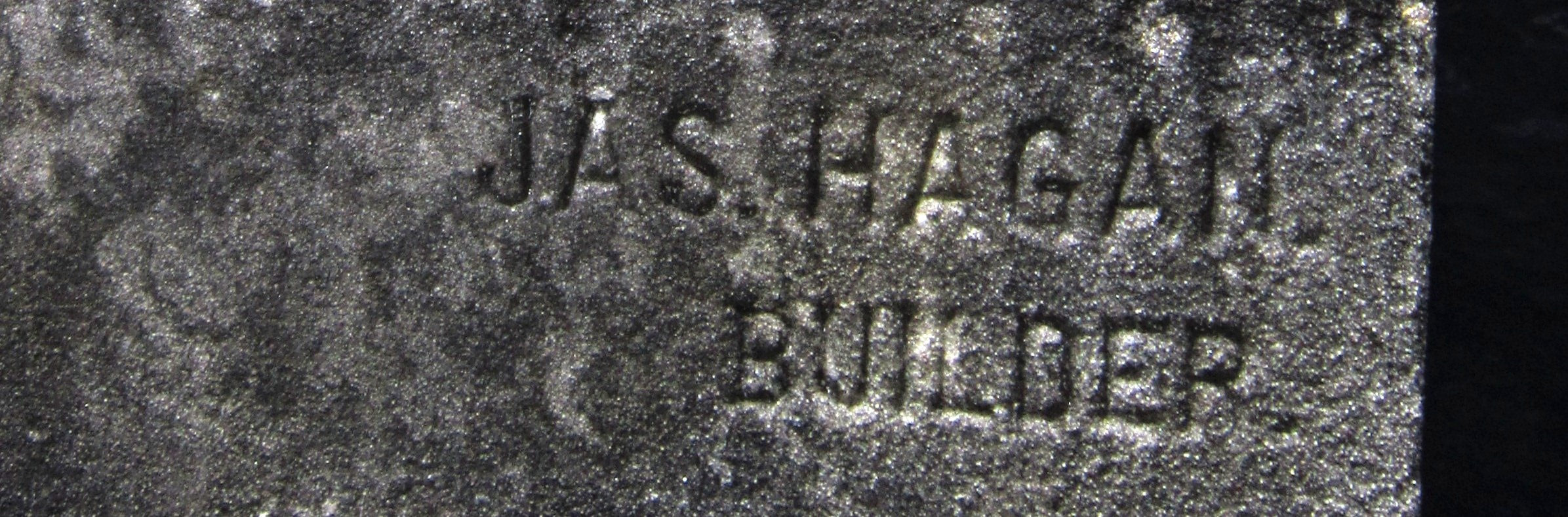

Irish-born Hagan was a state senator, a stonecutter, a real estate developer, and a dock commissioner in his long life, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was deeply shaped by his work. Along the main aisle of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, a pink granite tomb stands out from its lime-washed, marble-clad neighbors. Surrounded by a cast-iron fence, the tomb of James Hagan and John Henderson is often noted as the last resting place of a stonecutter whose work is prominent elsewhere in the cemetery. Yet this note, and the carved name of James Hagan, is only one small detail in the larger story of James Hagan’s life. James Hagan was not only a stonecutter but a real-estate dealer, state senator, community leader, and politician. He lived and worked in New Orleans not only in a time of great social change but a period of high craftwork and architecture in the city’s cemeteries. Among his signed works are some of the most ornate in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, all marked by detailed stonework and expensive marble cladding.[1] Sources suggest that James Hagan built the pink granite tomb not for himself but for his first wife, Mary Henderson, after her death in 1872. Hagan married Mary Henderson in New Orleans shortly after he immigrated from County Armagh or County Antrim, Ireland, in approximately 1852.[2] James Hagan and his brothers John, Peter, and Patrick, as well as their mother, all fled Ireland in the 1850s after famine likely forced them to emigrate. In the Fourth District of New Orleans, formerly the New Orleans suburb of Lafayette, the Hagans joined thousands of other Irish who had formed a community along the banks of the Mississippi River in the neighborhood now known as Irish Channel.

Published 144 years ago today in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, an interview with the assistant sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. It’s unclear how much of this article is speculative or fanciful, but in any case its content is fascinating. The article is presented here in pieces, with background inserted regarding the content. Original Times-Picayune narrative from July 13, 1873 is indicated in italics. Sitting on a Tombstone TALK WITH A GRAVEDIGGER --- “How long wil a man lie i’ the earth ere he rot?” [Hamlet] A reporter of the PICAYUNE, chancing in his peregrinations to stroll into the Washington Cemetery[1] in the cool of early morning, met and engaged in conversation with the assistant sexton. The term “sexton” is given to a person who maintains a cemetery in a professional capacity. It originated with a religious connotation, indicating a man who cared for both the church building and the adjoining cemetery. Later, as more and more cemeteries were established outside parish land, the term “sexton” migrated to the secular sphere. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as a municipal cemetery, and thus was never religiously affiliated. In 1873, the sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and 2 was Joseph F. Callico (1828 – 1885). Callico was a free person of color who worked for most of his career beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, and also beside fellow stonecutter Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. Around 1870, when Monsseaux himself ceased his business, Joseph Callico moved to Washington Avenue to serve as the sexton of the Washington Cemeteries. By 1875, he returned to St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, where his brother Fernand served as sexton.[2]

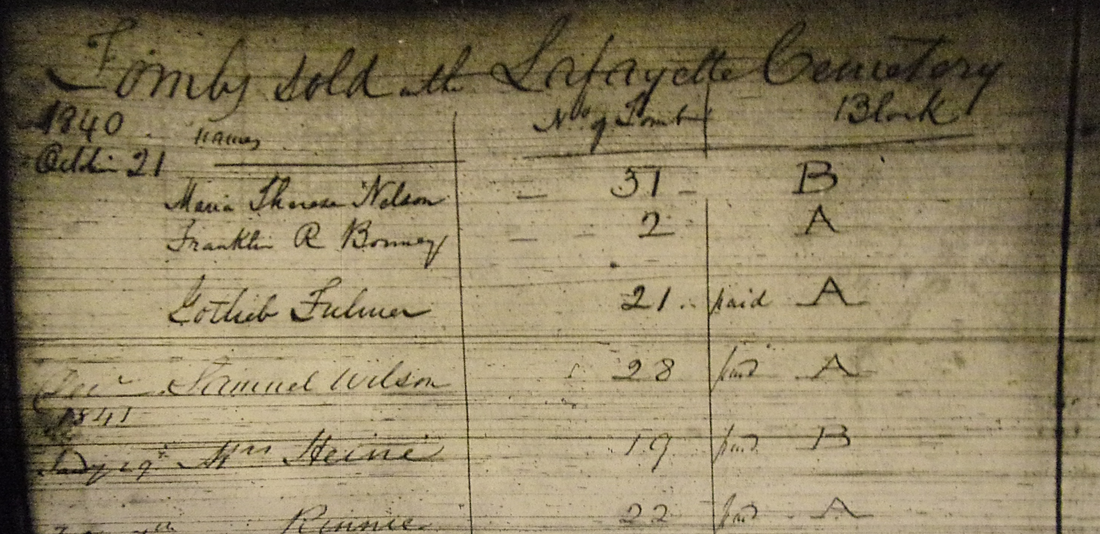

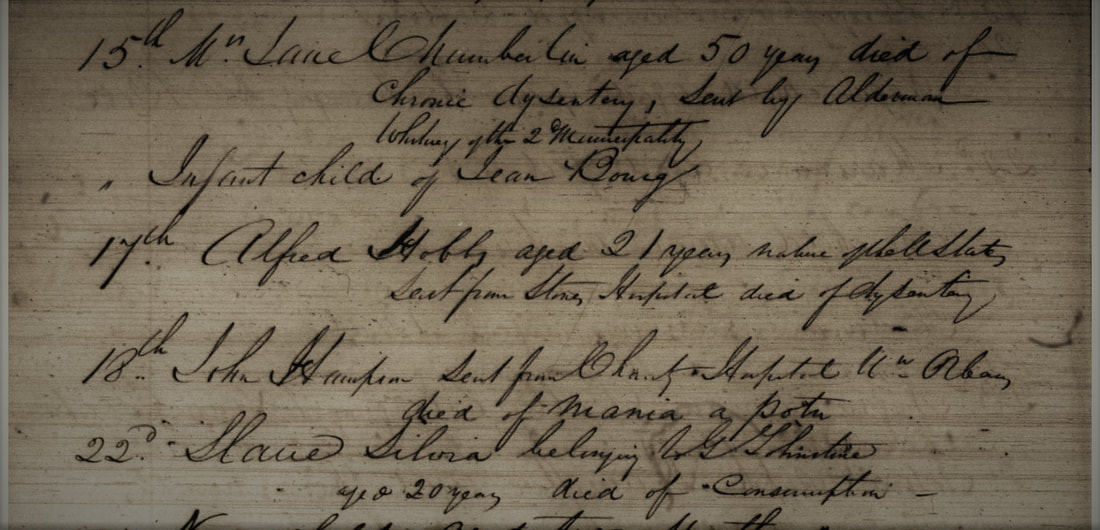

“Well, you know,” said the man, “there is a great difference in them. There are some here who, from their particular situation, keep much longer than others. There’s a man I came across the other day, digging a foundation for a tomb, who had been in the ground for two years, and he was in remarkably good condition. It is true, he was near the wall, and the drainage was good.” This passage offers some confirmation of what the landscape history of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 suggests: that earlier below-ground burials were replaced by above-ground tombs. Dr. Bennett Dowler wrote in 1852 that Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was a primarily a belowground cemetery, owing to the preference of Irish and German immigrants for inhumation over tomb burial.[4] Pre-1850’s burials in Lafayette No. 1 are difficult to find today, but most of which remain show some modification over time, suggesting that the assimilated children and grandchildren of immigrants later converted their family lots to traditional New Orleans tombs. This could be one reason the sexton came upon a burial while constructing a new tomb. The gravedigger expands on this notion in his next answer. “Do they bury many in the ground now in this cemetery?” “No,” said he “in this place most everyone has a tomb. You know, this yard has been buried some ten times over, and people don’t care to put their friends under earth when tombs don’t cost much more.” While “ten times over” may be exaggerated for Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in 1873, the cemetery was declared “full” by Lafayette and New Orleans city councils in 1847 and 1856, respectively.[5] Neither of these ordinances was paid much mind, and burials continued. Furthermore, in the earliest years of the cemetery, between 1833 and 1853, approximately 30% of the individuals listed in interment books are noted as enslaved people. Amounting to thousands if not tens of thousands of burials, records do not indicate their location, although they are unlikely to be in the cemetery wall vaults.[6]  Excerpt of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 interment books for August 1843. Over this week, burials included two deaths from dysentery, a twenty year old enslaved woman who died of consumption, and a death from "mania a potu," an historic term for alcohol-related illness, including delirium tremens. (New Orleans Public Library) From here both gravedigger and journalist get grim: “From your experience, what part of the body is the first to suffer from the effects of decomposition?” “The head goes first always. You see there isn’t so much flesh about it, and it doesn’t take long for it to go. The other parts go after it very soon; they all seem to go together.” While the good taste of asking this question in the first place is suspect, it is interesting to note the anachronism. In 1873, embalming had only recently become a possibility. The widespread practice of embalming starting in the twentieth century certainly affected the decomposition patterns of burials in New Orleans tombs and elsewhere. “In digging about these unoccupied places, do ever meet with the remains of human beings?” asked the reporter. “Oh, yes. The whole of Lafayette Cemetery has been filled, even to the avenues. When this was first a graveyard, it was not laid out regularly, and now when we have to repair the walkways, the bones are always turned up.” Prior to cement paving and other improvements that took place beginning in the 1940s, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1’s aisles were paved with crushed shells, marble pavers, and slate flagstones. Some of these paving materials remain visible. Archaeological test pits executed in the 1980s and 1990s indicated that crushed shells were regularly hauled into the cemetery to repave aisleways. This is likely the “repair to the walkways” the sexton mentions above. [more unnecessary description of decomposition] “Is there any difference between burying in the ovens and in the ground?” “Oh! Yes. In the ovens they don’t last six months, for with the metallic cases it does not take much time to destroy everything. In the ground, metallic cases, if they are good, last twenty years, and wooden ones about three."

"Yes! I have noticed that when they take on most they generally don’t come back to put flowers on the tomb much after the first month. “The widows come every week for about a month or two, fixing up everything. When they cry most they don’t come back at all, but when you see one who looks all the time at the coffin and doesn’t make a fuss you can be sure she will put flowers there for years.”

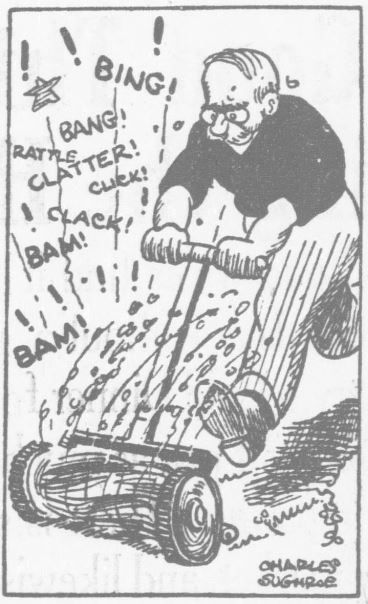

[1] Historically, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is frequently referred to as “the Washington Cemetery.”

[2] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84, 40; Edwards Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1872), 86; Edwards Annual Directory for New Orleans 1873 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1873), 90; United States Census, 1880, New Orleans, Louisiana, Roll 461, Page 234C. [3] “All Saints’ Day – The Living Remember the Dead,” Times-Picayune, November 2, 1873, 1. [4] Bennet Dowler, M.D., “Tableaux, Geographical, Commercial, Geological and Sanitary of New Orleans,” printed in Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1852 (New Orleans: Office of the Daily Delta, 1852), 21. [5] Mayoralty of New Orleans, Common Council, City of New Orleans, “An Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4. [6] New Orleans Public Library, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Interment Records, Vols. 1-5, microfilm. [7] Dowler, 21. To call any cemetery landscape “eclectic” is usually an understatement. Within cemetery landscapes are the architectural whims of uncountable individuals, families, and craftsmen. And so it goes that in New Orleans cemeteries we pass a Gothic chapel and find a Celtic cross. Our landscapes are amalgams of recollection – Classical Greek, Roman, and Egyptian are at home with the Italianate, the Moorish Revival, and the Art Nouveau. This rich tradition has inspired architects to look backward for inspiration, but there is no farther backward one can reach than the tumulus. Known also as a barrow, the tumulus is a burial structure that rises from the ground as a hill or mound. Often, the tumulus bears a means of access from the side or top of the hill. Its origins span across the ancient world, both Old and New, representing a common type of burial shared between the ancient Norse, Etruscans, Chinese, Native Americans, and many, many more.[1] This type of burial also has its home in New Orleans cemeteries. The Elks Lodge tumulus in Greenwood Cemetery, and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia in Metairie Cemetery are often used as examples for the tumulus in modern cemeteries. Yet they are not alone in their unique appearance. The tumulus once graced many more New Orleans cemetery landscapes than it does today. In this blog post, we explore the origins, proliferation, and eventual disappearance of the tumulus in New Orleans cemeteries. Mounds, Barrows, and Antiquarians In Europe, mound, barrow, or tumulus burial was practiced by pre-Roman and Roman cultures. Tumuli can be found in nearly every European country – today as protected archaeological sites and heritage attractions.[2] The practice of mound burial was abandoned after the rise of Christianity and the development of churchyards in Europe. Until the cemetery landscape was reinvented by the rural cemetery movement in the early 19th century, the tumulus was a thing of ancient history. A number of factors contributed to the reintroduction of the tumulus to cemetery landscapes in Europe and the New World. With the establishment of cemeteries like Pere Lachaise in Paris, the understanding of cemetery landscapes shifted into one of green space and architectural eclecticism. From this cultural development sprang the Greek Revival architecture that proliferated New Orleans thanks in part to J.N.B. de Pouilly. But the gaze of nineteenth century Europeans and Americans did not exclusively look back to Greece. It turned to Egypt and the Middle East. It incorporated Gothic spires into new designs. And it looked even farther back to the mysterious mounds found in the European countryside. By the 1870s, the antiquaries of Europe excavated numerous tumuli in England, Italy, France, and Norway. Such discoveries were commonly featured in New Orleans newspapers.[3] An awareness of the burial mounds of great ancient cultures joined Greek temples and Gothic cathedrals in the consciousness of New Orleaneans. Furthermore, the people of the American South were familiar with mound burial in their own backyards. The presence of seemingly abandoned mounds in the southern and mid-western United States had captured the interest of Europeans since Hernando de Soto reported their existence in 1541. After colonization and into the nineteenth century, some of these mounds in Louisiana were repurposed by Americans for use as their own cemeteries. This was the case in Monroe’s Filhiol-Watkins Cemetery. Fleming Plantation Cemetery is also located on a Native American mound. By the mid-nineteenth century, mound burial was firmly rooted in the imagination of New Orleaneans. From these inspirations, the tumulus made its debut in cemetery landscapes. The Tumulus in New Orleans Like the city itself, New Orleans cemeteries are the product of many layers of community and identity. Each cemetery is a reflection of the people who made it their own. Cemeteries that were built and utilized by Irish, German, or American New Orleaneans developed with a different aesthetic than those shaped by French speakers. Each community drew upon their own culture and style to create their cemetery. The tumulus entered the popular consciousness in part via a new interest in archaeology and ancient architecture.[4] Though tumuli in New Orleans often had Greek Revival motifs, they were utilized by Americans elsewhere in the United States. Great northern cemeteries like Mount Auburn featured tumuli as part of their cultivated agrarian landscapes, as did closer cemeteries in Charleston and Savannah.[5] Thus, it is no surprise that tumuli in New Orleans appeared first in American and not Francophone cemeteries – decades before the Elks, the Army of Tennessee, or the Army of Northern Virginia. Tumuli are found primarily in the Canal Street cemeteries, including Cypress Grove, Masonic, Odd Fellows Rest, and Greenwood. They are also found in American-oriented cemeteries like Lafayette Cemeteries No. 1 and 2. There are dozens of tumuli to be found in our cemeteries, yet the untrained eye will not find one. Hidden Tumuli, or How the Lawnmower Changed Everything Most tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries no longer look like tumuli. Stripped of their grassy hill features, they appear instead simply as unusual tombs with rounded bodies. The Hornor and Holdsworth tumuli in Cypress Grove and Masonic Cemeteries (respectively) are good examples. Both constructed with a marble primary façade featuring relief carvings of cut flowers, they were likely carved by the same craftsperson, although neither structure is signed. Both tumuli have conspicuously rounded structures that seem to contrast with the grandiose style of their primary face. Yet when imagined as they originally appeared, as green hills from which their marble faces projected, their aesthetic comes together. There are many former tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries that have been stripped of their signature mounds. The John P. Richardson tomb, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, was described in 1885 as “enclosed in a tall oval mound of turf, with marble doors set in a stone frame.”[6] The tumulus memorialized Richardson’s young daughters – Ella and Marguerite Callaway or “Calla,” ages six months and four years old. This original appearance could certainly not be deduced from examining the Richardson tomb today: its sweeping marble doors and arched primary face are attached to what appears to simply be a brick-and-mortar tomb. Dozens of former tumuli can be found in New Orleans cemeteries; most are identified by the slightly unusual appearance of the tomb body when compared to its front. Nineteenth century tumuli were designed to appear monumental in both mass and detail, with their entrances featuring sweeping side elements or rounded tops. The massive hill that comprised the tumulus body framed these features. Other examples of former tumuli include:  McIntosh tumulus, Cypress Grove Cemetery. In November 1873, the Nixon (now McIntosh) tomb was described as: "in the form of a mound overgrown with grass, with a large marble front. Along the top of the slab creeps an ivy, which will eventually cover the whole mound. The frontispiece was garnished on each side by a vase of white flowers." (New Orleans Republican) The disappearance of historic tumuli can be explained in the same way many other landscape features have been altered. As cemetery design, economics, and management changed, the tumulus was viewed as far too costly to maintain. Before the 1920s, cemeteries featured cultivated grounds with aisles paved in crushed shells – and they were manicured using manual, spiral-bladed lawn-cutters. Between 1920 and 1945, new lawnmowing equipment was patented with small gas-powered motors, cutting down on the labor required for landscape maintenance. This innovation was later supplemented by the availability of ready-mix concrete with which to pave once shell-strewn aisles. Finally, in the 1940s, industrialization of the monument and funerary industries led to most cemeteries eliminating the position of sexton (caretaker) from their ranks.

Each tumulus memorializes the fallen Confederate soldiers and deceased veterans associated with each division. After the Civil War, veterans of both Confederate and Union armies formed such benevolent associations for the support of their members. In the case of the Armies of Northern Virginia and Tennessee, perhaps the tumulus design was a nod to the military and fraternal connotations many ancient tumuli bear. Each tumulus features a remarkable sculpture at its hillside apex. The Army of Northern Virginia tumulus supports a 38-foot column atop which a sculpture of General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson stands. The Army of Tennessee features an equestrian bronze, sculpted by Alexander Doyle, depicting General Albert Sidney Johnston atop his horse, Fire Eater. Both tumuli are notable features of Metairie Cemetery, included in most histories of the cemetery.[7] The third notable tumulus in New Orleans is viewed daily by many city commuters. The tomb of the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, Lodge 30, features a bronze elk standing atop its grassy summit. The tumulus is located in Greenwood Cemetery at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, where the elk looks out above the traffic. The Elks lodge tumulus was first conceived of in 1911 by the local Elks, who held a great circus in downtown New Orleans to raise funds for the cause. In subsequent years, the Elks would commission monument man Albert Weiblen to construct the tomb at the cost of $10,000 (approximately $250,000 in 2016 currency). The structure was assembled of Alabama granite, shaped with a classical pediment, the center of which features a clock forever frozen at the eleventh hour, a reference to the “Eleventh Hour Toast” held by Elks when gathered together. Local legend has suggested that Albert Weiblen warned the Elks that the lot on which they wished the tumulus be constructed was not suitable for a structure of that size. It is true that, historically, City Park Avenue was once part of a navigation canal, an infill had only partially stabilized the soft earth. The story goes that the Elks decried Weiblen’s warning and enjoined he move ahead with construction. While primary sources for this story are nonexistent, the Elks Lodge tumulus does have a noticeable tilt toward Canal Street. Lessons in Preservation While the tumulus holds its place of honor in cemetery landscapes with the Elks and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia, it has faded from the everyday view of most cemeteries. Such a loss is difficult to quantify. Historic New Orleans cemeteries are dynamic places where features are constantly altered, modified, destroyed, or restored. Yet as we approach the task of preserving these cemeteries as functional landscapes, the tumulus offer some distinct lessons. Stripped-down tumuli confuse the historic appearance of cemeteries like Cypress Grove and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Had these structures been preserved, their green mounds would carry on the tradition of the cemetery as garden space; and they would properly communicate the historic landscape for both grieving family and heritage tourist alike. Stripped-down tumuli are an example of one cardinal rule of cemetery preservation: that once improper treatment has taken place, it’s nearly impossible to reverse. Each blow to responsible and considerate preservation is most likely permanent. Thus, while restoration is important, maintenance, documentation, and planned preservation are much more crucial. When the cemetery landscape is understood and preserved, large-scale restorations are less necessary. Finally, stripped-down tumuli teach us to deeply consider each structure as part of a whole, to read the structure for what isn’t there as much as for what is. Through this consideration, cemetery stewards can preserve these resources of history and heritage in a responsible manner that benefits generations to come. [1] Dan Hicks, et. al. Envisioning Landscape: Situations and Standpoints in Archaeology and Heritage (Routledge, 2016), 167.

[2] James C. Southall, The Recent Origin of Man (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1875), 87-97. [3] “Jackson Mounds,” Daily Crescent, January 16, 1851; “Norwegian tumulus,” New Orleans Bulletin, April 8, 1874, 2; “Norwegian Tumulus,” Opelousas Journal, August 4, 1876, 1. [4] George F. Beyer, “The Mounds of Louisiana,” in Publications of the Louisiana Historical Society (New Orleans: 1895), 12-30. (Link) [5] Gibbes tumulus, Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, SC, and HABS documentation (Library of Congress). [6] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1885, p. 2. [7] Henri Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery, An Historical Memoir: Tales of its statesmen, soldiers, and great families (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, 1981). Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. Beyond sweeping landscapes and imposing architecture – within the “stories in stone” that are so beloved in New Orleans cemeteries, are the stones themselves. Much like the long-dead people they memorialize, these slabs of honed and carved limestone, marble, and granite journeyed great distances to become part of an irreplaceable cemetery landscape. Whose hands drew that stone from its quarry? Why is the marble found in Greenwood Cemetery drastically different from what we find in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2? Today we share the stories of quarries, infrastructures, and materials that make up New Orleans cemetery stonework. Louisiana Lacks Workable Native Stone The geology of southern Louisiana is similar to that of other states along the Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of mostly sedimentary rock, clay, limestone, and sandstone, Louisiana has few stone resources that would be desirable for cemetery monuments.[1] Furthermore, the stone that is quarried in Louisiana has historically been of poor quality for building. For example, during the 1850s construction of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., requests were made that each state donate a block of native stone to be placed in the interior of the monument. Louisiana sent a block of sandstone that, within the decade, was so crumbling and decayed that it was replaced with a block of Pennsylvania marble.[2] Thus, from the eighteenth century onward, the stone used in New Orleans cemeteries was imported from elsewhere. Various types of slate, marble, and granite were made available as trade routes and quarries opened. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans merchants and dealers offered stone from a number of different places. As time went on, the availability and sources of stone widened.

Arkansas slate was quarried from areas near the towns of Hot Springs, Little Rock, Benton, Malvern, or Mena. This small vein of quality slate, approximately 100 miles long, could produce stone of red, gray, green, or black appearance. Despite the availability of slate from Arkansas, Pennsylvania slate continued to be quarried and shipped to New Orleans. Historic Louisiana newspapers frequently mention the quality and availability of slate from the Bangor quarry in Northampton County. Given the same name as a slate quarry in Wales, the “Old Bangor” quarry had an office in New Orleans by the 1870s. Old Bangor slate is “very dark gray, and to the unaided eye has a fine texture and fine cleavage surface, almost without any luster. The sawn edge shows pyrite.” The Williamstown, Franklin, and Pen Arygl quarries of Pennsylvania also had retail agents in New Orleans, who advertised their slate to be of the same quality as that of Wales.[6]

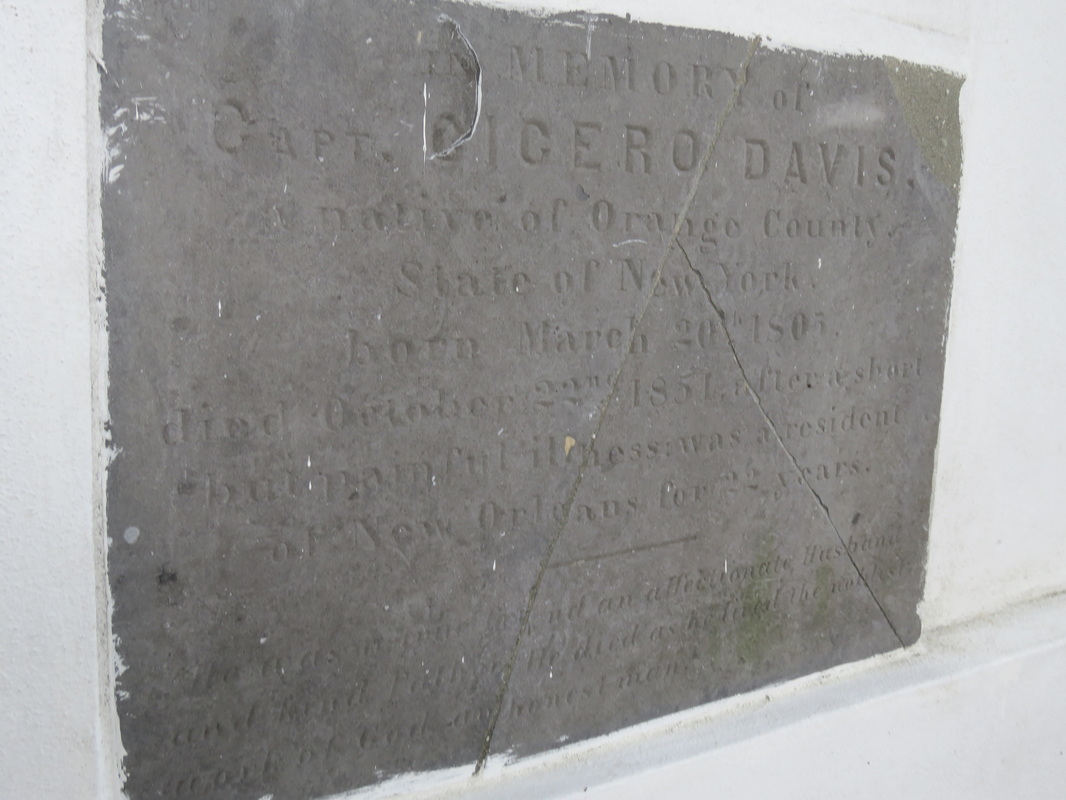

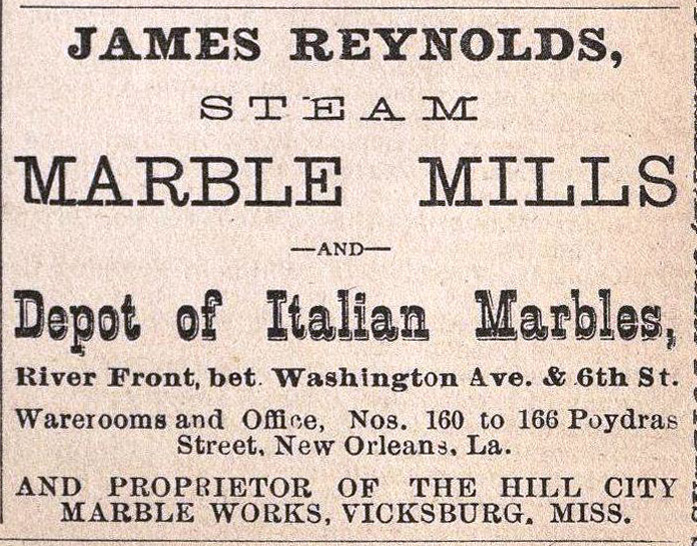

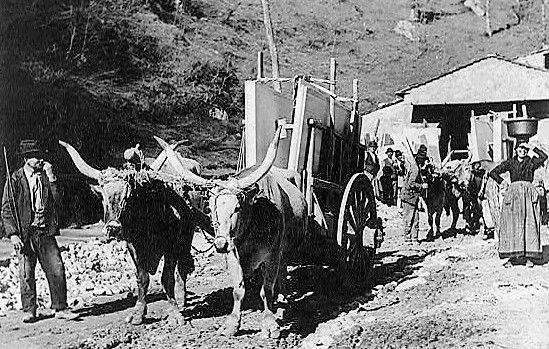

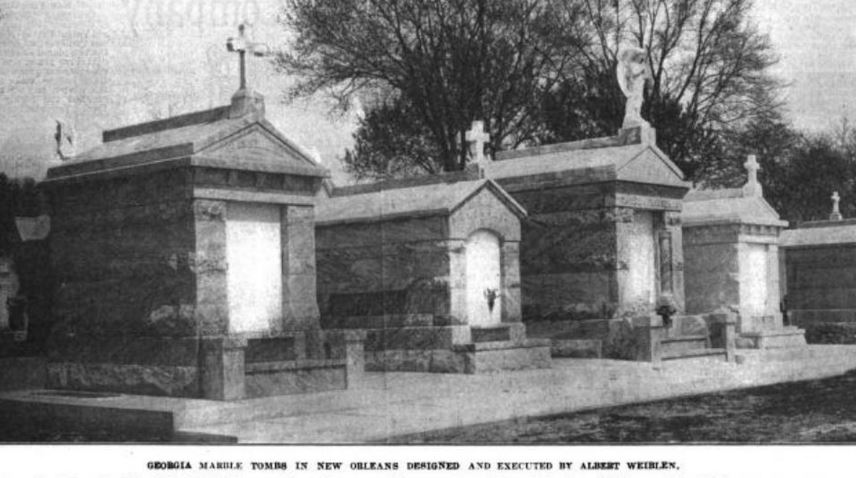

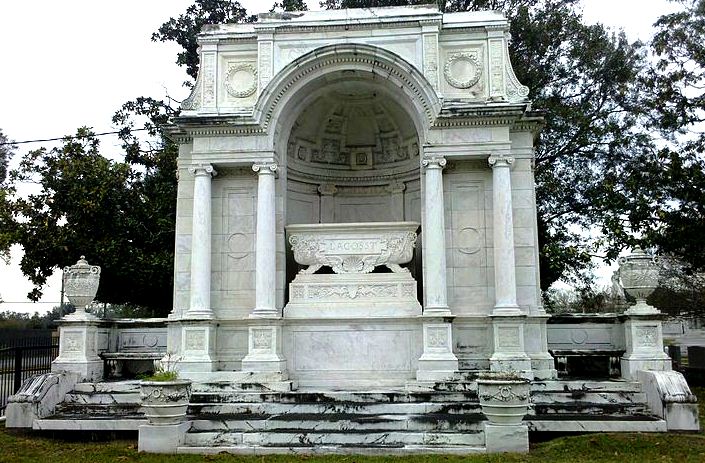

They form by the compression of these sediments, along with all the calcium-rich seashells within. They diverge when these sediments either compress and become sedimentary rock or, alternatively, are subject to higher pressures and become metamorphic. Limestone is sedimentary, marble is metamorphic. Limestone is most prevalent in the oldest remaining New Orleans cemeteries, namely St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, although precious isolated examples are found in other cemeteries. In this context, limestone was used for closure tablets. Limestone closure tablets are usually dark gray (likely quarried in Arkansas or Tennessee) and can be identified by the tiny fossilized shells included in the stone’s matrix. Around the mid-nineteenth century, whiter limestones were used in the same context as marble and are harder to identify. Some rough-faced stones that appear to be marble can be identified as limestone by spotting the shell inclusions within. These rare examples of white limestone were often quarried in Tennessee. Imported Marble: An Italian Commodity New Orleans was a primary hub for the import and export marble from both Europe and the United States. Used for closure tablets, shelves, memorial sculpture, apex sculptures, tomb cladding, and other decorative elements, marble was the medium in which cemetery stonecutters primarily worked throughout the nineteenth century. Based on documentary evidence, the quarries of Italy were the primary source of marble into the 1850s. Italian marble was either directly imported from Italy or arrived via northeastern ports like Boston or New York.[7] Florville Foy, who advertised aggressively throughout his career, frequently promoted his most recent shipment from Carrara or Genoa, cut into one, two, and three inch slabs. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux similarly advertised his Italian marble stock.[8] New Orleans stonecutters dealt in and imported Italian marble through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, stonecutter John Hagan (active 1854 – 1890s) stocked Italian marble “for sale at a small advance on New York prices.” George Stroud (active 1866 – 1899) cut his own Italian marble at Monsseaux’s steam cutting plant. James Reynolds (active 1866 – 1880) not only sold his Italian marble in New Orleans but also in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[9] Italian marble, often vernacularly referred to as “Carrara marble” regardless of its quarry of origin, is a stone of high-grade, consistent quality, and a variety of colors including cream, pure white, and blue. As one Alabama quarry owner conceded in 1909, “Italian marble has long been a standard, not only because the stone is undeniably high grade, but also because the blocks are so uniform in quality that all the slabs or pieces from a block can be used together.”[10] The cost of importing marble in New Orleans varied over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century; at times, it actually cost less to import than marble from Vermont or Tennessee. Protective tariffs helped to stabilize the marble industry during the 1880s and 1890s, but the presence of the famed marble remained a factor among monumental craftsmen into the present. For example, in 1914, before Albert Weiblen purchased his own marble quarry in Georgia, he received a shipment of Italian marble so substantial it took two large derricks to lift the fifteen-ton blocks from the steamship in which it arrived.[11] Domestic Marble: Vermont, Alabama, Georgia, and Others The slow development of infrastructure and quarry technology prevented American quarries from competing with Italian marble in New Orleans until the 1850s. In 1845, one of the first marble quarries opened in Talladega County, Alabama. Five years later, another opened nearby, operated by J.M.N.B. Nix. Using a publicity tactic that would become common among quarry operators in the United States, the New Orleans Daily Picayune announced that “Alabama produces marble equal in fineness – that is, purity or clearness and susceptibility of polish – to any in the world, not excepting the most beautiful Italian, Vermont, or Egyptian.” It was Nix’s quarry that sent Alabama’s contribution to the Washington Monument.[12] Talladega marble can appear white, blue, or cream, and often displays black, green, or grey veins, although it is consistently characterized by the fineness of its grain. Its unpredictability in quality and appearance, however, made it costly to extract.[13] Alabama marble remained a presence among New Orleans cemetery craftsmen well into the twentieth century. One of the most recognizable and imposing monuments within Metairie Cemetery, the ornate sarcophagus of Eugene Lacosst, was crafted by Albert Weiblen from pure white Alabama marble.[14] As always, infrastructure dictated which materials were available in New Orleans at a given time period. In 1851, The Vermont Valley Railroad Company connected towns like Rutland to the greater markets in the East and South.[15] Only two years later, sources in New Orleans commented on the great productivity of the Rutland quarries, remarking that their product had gained “a reputation abroad as well as at home.”[16] Rutland and other Vermont marbles can be white, blue, or black. These quarries also produced pure-white sculpture-grade marble.[17] By 1900, Vermont produced more marble than any other American state, and the Rutland quarry was the highest-yielding quarry. Blocks of Vermont marble were sold for between $1.00 and $3.00 per cubic foot in New Orleans, where agents received shipments and distributed order throughout the South and West.[18] Like Alabama marble, marble quarried in Vermont remained in the stockpiles of New Orleans craftsmen into the mid- and late twentieth century. Vermont not only exported its marble to New Orleans, but its marble cutters as well. One account reflected that the stone cutting yards of New Orleans primarily employed skilled sculptors and polishers from the states of Vermont and Georgia.[19] By 1916, Georgia was second only to Vermont in its production of quarried marble. Although marble quarrying had existed in Georgia long before, it appears to only have gained prevalence in the New Orleans market after the Civil War. By 1888, the Georgia Marble Company in Pickens County claimed to be the largest marble quarry in the world.[20] Georgia marble is typically coarse-grained and appears in blue-gray, black, white, and Creole, which has dramatic sweeping shades of dark gray, black, and white.[21] Ubiquitous Georgia Creole Marble Between 1890 and the 1930s, Georgia Creole marble exploded in the New Orleans cemetery market and made an enormous mark on the landscape. This explosion was the result of expert marketing, improved infrastructure, and enormous supply. Modern monument men during this period utilized Georgia Creole marble in nearly every aspect of their work, from tomb cladding to headstones to vases and urns. The streamlined process of tomb building, now executed in a more “cookie cutter” style than previous generations, allowed many more tombs to be built in a short period of time, and Georgia Creole marble was the medium of choice.

Additionally, as marble is a metamorphosed type of limestone, it is naturally alkaline in quality. Thus, exposure to rain, which is naturally slightly acidic, or any other acidic substance (for example, hydrochloric acid mistakenly intended to clean the stone) will cause marble to granulate and “sugar” over time. An extreme example of marble deterioration can be found in St. Joseph’s Cemetery No. 1. The failure that likely occurred with this stone was related to moisture entrapment within the tomb itself. This, paired with the tight, compressive position of the tablet within the opening, caused the closure tablet to bow and “bubble” outward.

One of the most noticeable granite tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is that of stonecutter and sexton James Hagan. This remarkable tomb was built of red-colored Scotch granite in 1872. Around the same time, Hagan also constructed the monument of Governor Henry Allen, which was also located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 until it was moved to the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the 1880s. This monument, too, was carved from Scotch granite.[24]

[1] Louisiana Geological Survey, Geology and Agriculture: A Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1902), 133-134.

[2] National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Northeast Region, Architectural Preservation Division, The Washington Monument: A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2005), 28. “Washington National Monument,” The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 22, 1850, page 1. The stone is referred to as “freestone,” meaning a soft, friable sedimentary stone. [3] Graham R. Thompson and Jonathan Turk, Introduction to Physical Geology (Rochester, NY: Saunders College Publishers, 1998), 133-137. Slate headstones are found commonly in the Northeast dating to the colonial period. Slate headstones are also present in cemeteries as far south as Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. However, no slate headstones are visible in the cemetery landscapes of New Orleans. [4] Mary Louise Christovich, Roulhac Toledano, and Betsy Swanson, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. I: The American Sector (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 1998), 57. [5] Daily Picayune, September 27, 1850, 2; Daily Picayune, May 2, 1853, 1; Daily Picayune, February 28, 1869, 11. [6] “Alexander Hill, Welsh and American Slates, Slabs, etc.” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 4, 1875, 6. These slates priced from $6.50 to $10 per square; “Slates! Slates! Slates!” Ouachita Telegraph (Monroe, LA), July 22, 1872, 2. [7] “Brig Casket arrives from New York with sundry marble slabs,” Louisiana Advertiser, April 29, 1820, 3. “Barelli & Company, commission merchants, selling blocks of Italian marble,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1845, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 10, 1848, 7; Daily Picayune, February 17, 1848, 3; Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1851 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1851), page AT. [9] Edwards’ Annual Director to the Inhabitants, Institutions….etc., etc., in the City of New Orleans for 1871 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1870), 275; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [10] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. [11] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8. [12] “Alabama Marble,” Daily Picayune, October 1, 1845, page 2; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [13] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. In this year, cost to transport Alabama marble to New Orleans was 32 cents per cubic foot. [14] Leonard V. Huber et. al. New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 54-55. [15] Vermont Railroad Commissioner, Eleventh Biennial Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of Vermont (St. Albans, VT: St. Albans Messenger Co., 1908), 308. [16] Daily Picayune, July 15, 1853, page1; Daily Picayune, June 16, 1855, 1. [17] Thomas Nelson Dale, The Commercial Marbles of Western Vermont (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 117-122. [18] Tariff Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means, Second Session, Fifty-Fourth Congress, 1896-97, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 275-279; “Random Notes,” The Reporter: The First and Only Journal Published in the World Devoted Exclusively to Granite and Marble, No. 1 (January, 1900): 33. [19] David Spence Hill, Industry and Education: Part Two of a Vocational Survey for Isaac Delgado Central Trades School (New Orleans: The Commission Council, 1916), 227. [20] “Science and Industry,” The Colfax Chronicle (Colfax, LA), November 3, 1888, 3. This was not an uncommon claim for many quarries to make. “Georgia Quarries,” The True Democrat (Bayou Sara, LA), January 30, 1897, 7. [21] Memoirs of Georgia, Vol. I (Atlanta: The Southern Historical Association, 1895), 211-217. [22] A. Oakley Hall, “Cities of the Dead,” in Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers Tales and Literary Journeys, Frank de Caro, editor. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998), 532-533; Arthur Wellington Brayley, History of the Granite Industry of New England, Volume I (Boston: National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913), 114. [23] Ibid., 84. [24] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley of Durham University, UK, for his knowledge and expertise in identifying the Hagan tomb as Scottish granite. [25] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1895), 1095. [26] “Notes from the Quarries,” Stone: an Illustrated Magazine Vol. 4 (1892): 496. This blog post is Part Two of a two-part piece on the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. To learn about the history of this French Society, check out Part One here. Recently, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC transcribed the burial records of the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, thanks in part to a grant from genealogist Megan Smolenyak. The Society was absorbed by the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans in 1900. About the Record Books The records of the Sociètè are housed at LSU Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, in Baton Rouge. (MSS 318, 1012) The burial books appear to have been included with the larger collection of papers from the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (French Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society of New Orleans) which absorbed its Jefferson City counterpart in 1900. The collection is comprised of two books, dating from the tomb’s construction in 1872 through 1900. While later interments were certainly made in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb, their record appears to have been incorporated into another, as-yet unstudied document. Within these two books are the burial documents for 186 individuals. Among these records, 142 people were buried in the society tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, 32 were provided formal burial aid by the society and were interred in family tombs throughout the city, and 12 were not specified as to burial location.[1] Each burial record documents the date and place of the individual’s birth, date and place of death, as well as cause of death and information regarding membership. These documents shed light on the lives of hundreds of people. They allude to intricate familial and professional relationships, personal tragedies, and public calamities. They offer a window into a rich community, the vestiges of which stand silent in this stately yet neglected tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Today we share the stories of those buried within. The Foreign French: Founding Members and their Origins The Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson was organized in 1868 by native-born French men – eight of whom are buried in the Lafayette No. 2 tomb. Much like the New Orleans French society, these immigrants sought fraternity among their countrymen. Incidentally (or perhaps not so much so), most of these men were born in the same French provinces (départments), and often in the same village. The majority of adults buried in the Sociètè tomb originated from two primary areas in continental France: the department now known as Midi-Pyrenees, including Gers, Haute-Pyrenees, Haute-Garonne, and Bass Pyrenees (now known as Pyrenees-Atlantiques), and the eastern departments of Alsace-Lorraine, specifically Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin, and Moselle. These two areas are nearly as geographically disparate as can be, with the former nestled along the Pyrenees mountains at the Spanish border, and the latter at the Rhine River beside present-day Germany.

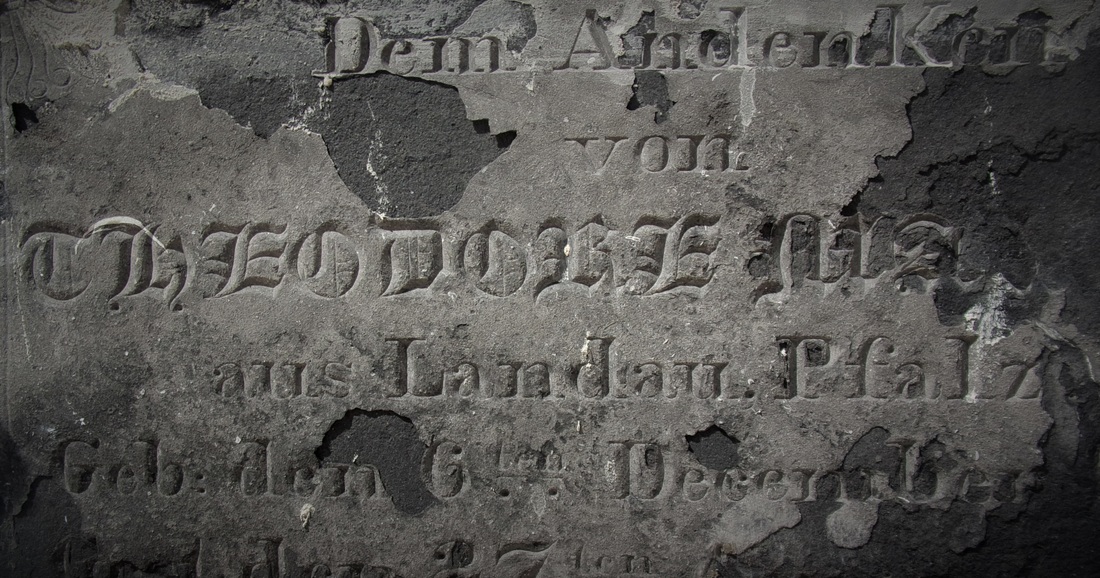

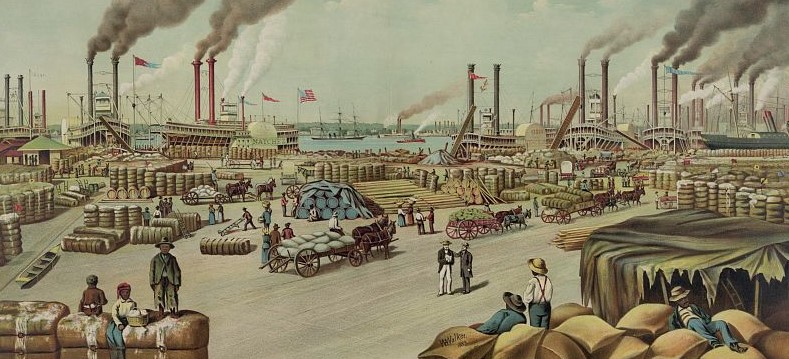

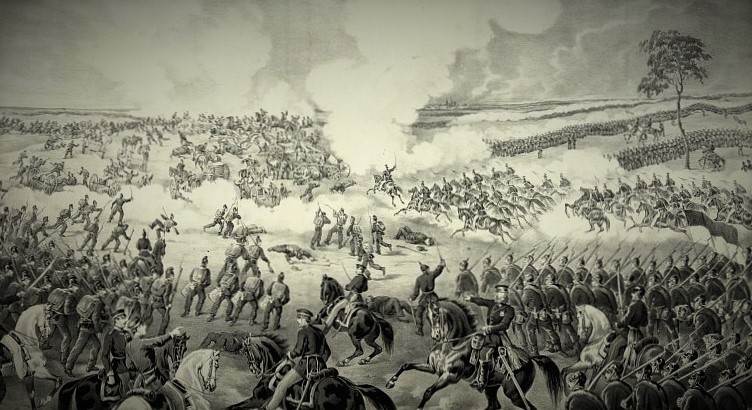

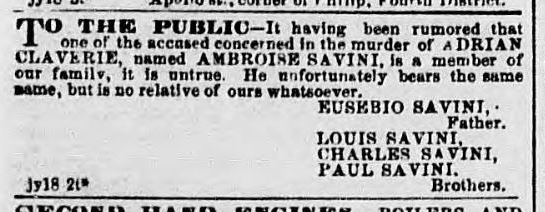

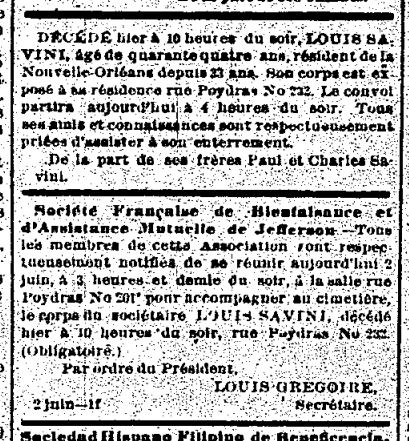

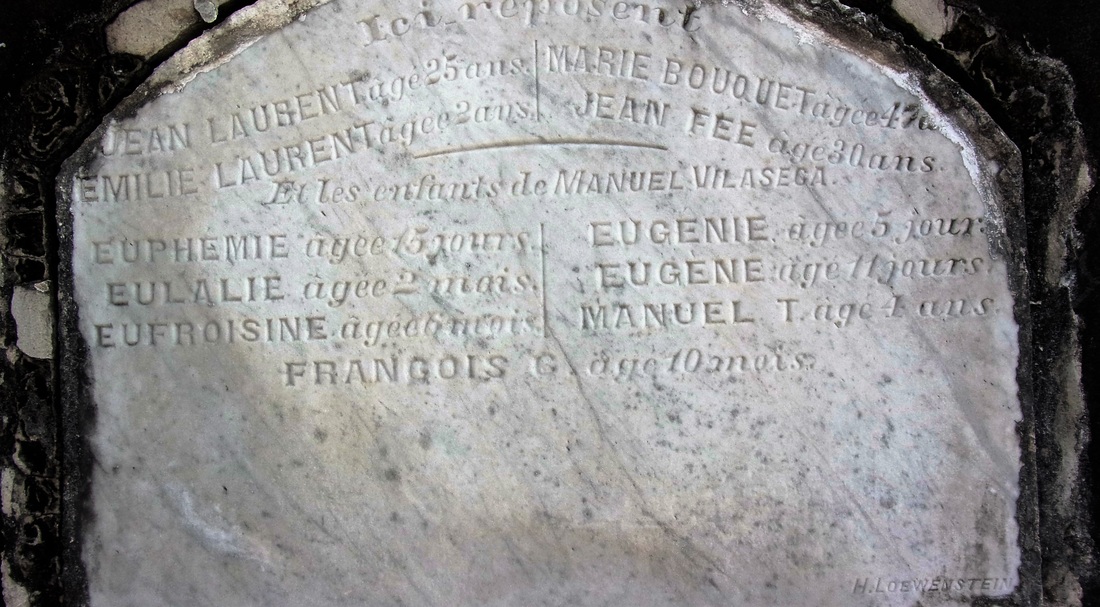

In Alsace-Lorraine, a different climate motivated the eventual members of the Sociètè to emigrate from their homes. The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) forced many Alsatians from their homeland when the controls of the provinces shifted from France to newly-nationalized Germany. For French-speaking Alsatians, both Jewish and gentile, German citizenship was a less than desirable option. New Orleans was an attractive alternative due to its Francophone tradition. Among these Alsatian emigrants were sisters Catherine and Marie Sonntag, both in their early twenties from Altinstadt, Alsace. Nieces of Sociètè member O.M. Redon, they both died of yellow fever within weeks of each other in October 1872. They were buried in vaults 20 and 22 of the Lafayette No. 2 society tomb. While the people buried in this tomb overwhelmingly shared a linguistic and cultural bond, there is no shortage of strangers among the burials in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Although the tomb was built for French society members, those members were not always French. Strangers in a Strange Land: Non-French Buried in the French Tomb A handful of foreign-born non-French people were laid to rest in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. Their stories contribute to the greater narrative of the society which at its heart was thoroughly New Orleanean in its cultural interactions. From Germany, Catherine Deffenback and brothers John and Jacob Schwenck were buried in this tomb at their time of death. The Schwenck brothers owned a saloon together on Magazine Street.[3] Leon Vignes, from Mont-de-Marrast, France, mourned the death of his Irish-born wife, Margaret, in 1884. She is buried in vault 35. Leon died fifteen years later and was buried in vault 38. He was not the only person to join the matrimonial melting pot: The wife of J.M. Gelé was born in England and died in 1872, buried in vault 26. Perhaps the most interesting foreign-born member of the society is not buried in the Lafayette No. 2 tomb but instead only blocks away in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, although no tablet remains to mark his name. Louis Savini was born in 1830 in Mortara, Italy. By the time he was eleven years old, he and his family had taken residence in New Orleans. From the very scant documentation remaining, Savini appears to have led a colorful life. He owned a saloon in what is now the Central Business District on Common Street, near the Mississippi River.[4] For reasons unclear from available records, Savini joined the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson in 1874. Only months after joining the group, however, Savini was struck down by a “cerebral fever,” which could indicate encephalitis, meningitis, or scarlet fever. He died on June 1, 1874 in his home on Poydras Street. The Sociètè not only furnished his burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, but also provided a procession befitting a French society member. Savini was buried in the tomb of his brother, Paul Savini, in Quadrant 2 of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Today, the tomb is in a state of dangerous neglect and has lost the closure tablet bearing Louis Savini’s name. As the Sociètè aged, its members increasingly were New Orleans natives. Over time, both the children of members and other Francophone Louisianans joined, advancing the process of assimilation in a new country. The Family Tomb At least one hundred and forty-two individuals are buried in the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Some were recent immigrants with little or no family left behind. For a striking number of society members, however, the tomb was the final resting place for multiple generations. It has already been noted that Leon and Margaret Vignes rest near each other in this tomb. They are also interred with their son, Joseph, who drowned at the age of 14 in 1891. He is interred in the same vault as his mother. The Fortassin family likely also utilized the society tomb for the interment of multiple generations. In 1870, twenty year-old Gabriel Fortassin, Jr., arrived in New Orleans from Trie, France. His parents joined him as well. In 1882, he married Alexandrine Claverotte.[5] The two would briefly move to San Antonio, Texas before returning to New Orleans. In his lifetime, Gabriel would bury his parents in the society tomb, as well as five of his infant children. When he died in 1927, he was given a French Society burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2.[6] One of Gabriel’s adult sons, Baptiste Fortassin was also buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, in 1929. Two years later, Baptiste’s widow Marie Maille joined him. With no Fortassin tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, it is very likely they joined their relatives in this tomb, making it the last resting place of three generations of one family, with at least nine burials.[7] Other families utilized the society tomb similarly. Surnames such as Tujague[8], Abadie, Mouledous[9], Vignes, and Carrare appear multiple times through the burial books, representing multiple generations. These records also show combinations of the above-mentioned names, linked by intermarriage. Eleanor Vignes Tujague and Pauline Mouledous Tujague are both buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. Society members formed a strong, interdependent community. They even stood at each other’s deathbeds to witness a last will and testament.[10] Death and burial were only the final threads that tied these French-speaking New Orleaneans together. In life, they lived and worked beside one another. As the French Society of Jefferson, members lived predominately within the boundaries of the former Jefferson suburb (portions of present-day Garden District, Irish Channel, Central City, and Uptown neighborhoods). Burial records note the residences of a multitude of members as near the St. Mary’s Market and along Tchoupitoulas Street. Even more records note residence as simply “aux abbatoirs,” or “near the slaughterhouses.” Which is no surprise: the majorit of members were butchers. A Workingman’s Society The Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson shared members and celebrated social events with the Sociètè de Bienfaisance des Bouchers, or the French Butchers Society. Their enormous, eighty-vault society tomb remains also in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Members of each society lived near the Mississippi River, where cattle were unloaded at river docks. Until the late 1860s, the City of New Orleans had little regulation regarding the slaughter of livestock. Butchers were free to practice their trade where they pleased, usually near a market where they could sell their wares. This changed with a municipal law that required butchers slaughter livestock exclusively in a city-owned slaughterhouse, the goal of which was to prevent public health hazards.[11] Opposition to this law among butchers of both French societies led to civil unrest and years of legal battles. The case finally reached the Supreme Court in a landmark ruling known as the Slaughterhouse Case. Among the French and Butchers societies, the butcher’s trade was passed through generations and within a tight-knit community. Members lived in close proximity to each other, with addresses at Louisiana, Camp, Chippewa, Annunciation, Constance, Josephine, St. Mary, Tchoupitoulas, St. Andrew, Washington, Magazine, and Rousseau Streets. The propensity to take on the butcher’s trade among these society members is truly overwhelming. One casual cross reference of members’ names with an 1878 directory revealed nine butcher/members alive and working at the time: Gabriel Fortassin, Jr., Jean Abadie, Joseph Barrere, Pierre Lacaze, Bernard Lacoste, John William Lannes (Lannis), Pierre Sabatte, and Leon Vignes. The other three members searched, Victor Brisbois, Ulysses Mailhes, and Jacob Schwenck, were all listed as saloon owners or bartenders. Causes of Death If cursory research is to be trusted, the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson was populated by close friends who slaughtered animals and served alcohol for a living. When this living ended for each individual, however, the causes varied. It should be noted that 65 of the 142 burials (45%) in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb were for children under six years of age. The Fortassin family, who buried five children in this tomb, were by no means unusual in their parental grief. Joseph Bararre and his wife Amanda Mailhes buried four children as well, all of whom were interred in vault 8. The high concentration of child burials in this tomb has a dual explanation. In addition to the well-understood status of childhood illness and mortality in the late nineteenth century, it was also much more likely for a family to bury a child in a society tomb than one built for a family. Married couples without their own family tomb were unlikely to purchase a lot for the burial of a child or stillborn infant. Instead, it was much more affordable to inter the child in a wall vault or society tomb, if available. Furthermore, the spiritual and emotional benefits of society-supported burial of a child were likely comforting. A significant percentage of the 65 infant/child burials were the stillborn or nonviable infants of society members. The other children of the Sociètè died of many common childhood maladies, including lockjaw (tetanus), cholera, croup, seizures, and whooping cough. Six children were listed as having died either of “bad teething” or a jaw ailment. In the nineteenth century, a range of many ailments was attributed to the process of teething in toddlers, including intestinal disease, seizures, meningitis, or even crib death. About half of the burial records in the Sociètè burial book list a cause of death. Among the adult members, most causes of death of typical of the time period: apoplexy, Bright’s disease, consumption (tuberculosis), and yellow fever. Surprisingly, only four burial certificates mark yellow fever as cause of death. This statistical anomaly may be explained by society members being buried hastily during times of epidemic, either in other tombs or too quickly to fill the burial form completely. “A Mort et Sans Espoir de Guerison” A few members, however, appear to have died in a slightly more unusual manner. Among them are:

All of the above-listed men were members of the Sociètè who were buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb alongside lost children, fellow butchers, and more than a few bartenders, as well as many wives, nieces, and grandchildren. A Community Buried Together Nearly all vestiges of Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson have faded from popular memory. The tomb itself does not have a single carved name on any of its forty marble vault tablets. Yet within the decaying stucco vaults of this tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 are the relics of a great communal history that remains vitally significant to New Orleans cultural heritage. It is the hope that this research might connect the descendants of those buried in this tomb with their ancestors. The full burial rolls of interments into this tomb from 1872 to 1900 (up to the society’s merger with Sociètè Française d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans) have been uploaded to FindaGrave, in hopes their descendants may find them. The burial books are also available as an Excel Spreadsheet , MS Access Database, or PDF Document. Click here for burials listed by vault number. [1] Unless otherwise noted, all content is referenced directly from the original burial books as transcribed and documented by Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Links to these materials can be found at the end of this blog post.

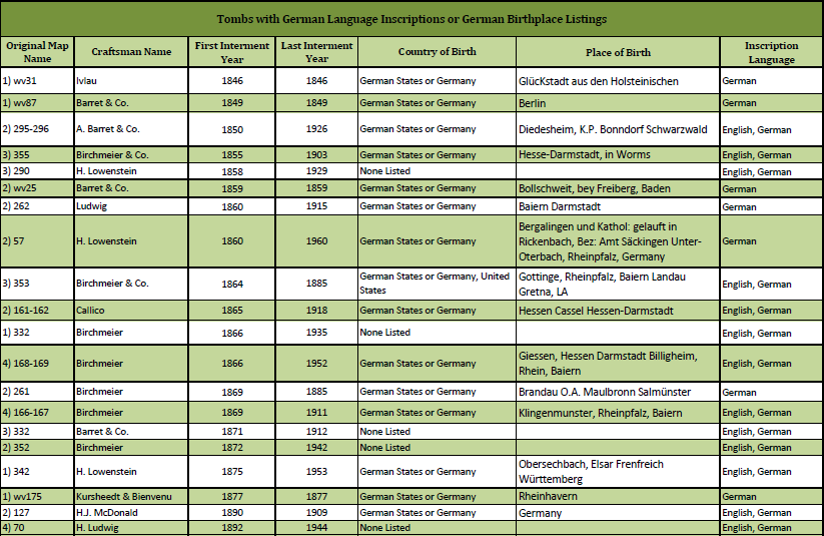

[2] Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon, editors. Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1992), 112. [3] Edwards’ Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans, for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company 1872), 366. [4] New Orleans City Directory 1870, 531. [5] State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History. Vital Records Indices. Baton Rouge, LA, USA. [6] Times-Picayune, August 28, 1927, 2. [7] Times-Picayune, January 18, 1929, 2; [8] To our knowledge, if this family is related to Guillaume Tujague, restauranteur, it is only distantly. [9] Alternately spelled Moledous, Mouledoux, etc. [10] Pierre Lacaze, also from Trie, witnessed Sylvain Tujague’s final will in 1882. Louisiana Will Book, Vol. 21 (1880-1883). [11] “City Litigation,” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, May 30, 1869, 5. In this article regarding the Butchers’ filed injunction against the City, the author notes their injunction as “a string of reasons as clear and cutting as the keenest cleaver could demonstrate.” Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Throughout the course of the nineteenth century, the New Orleans Jewish experience varied among individuals and families, from great successes to great defeats. For some, it was something one was born into: by mid-century, a number of families had developed deep roots in New Orleans commerce and culture. For men like Judah P. Benjamin and other merchants, lawyers, and factors, New Orleans was a place of opportunity among aristocrats and politicians. For others, however, New Orleans was a refuge, only slightly improved from the poverty and exclusion of the homeland from which they had fled. Among the Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who immigrated to New Orleans between 1840 and 1880, many found their new home to be wracked by destitution, disease, and an uncertain future. These immigrants formed their own communities, establishing a familiar cultural norm to ease their transition in the New World.[1] Two New Orleans stonecutters exemplify this wide spectrum of experience. Edwin I. Kursheedt, part of an influential Jewish family, was successful not only professionally but personally. Committed to charity and military service, he inherited his business from his father and carried it into the twentieth century. Alternatively, the carved signature of H. Lowenstein is nearly all that remains of this stonecutter’s legacy. It is likely that his time in New Orleans was brief, cut short by disease, war, or the search for better opportunities.

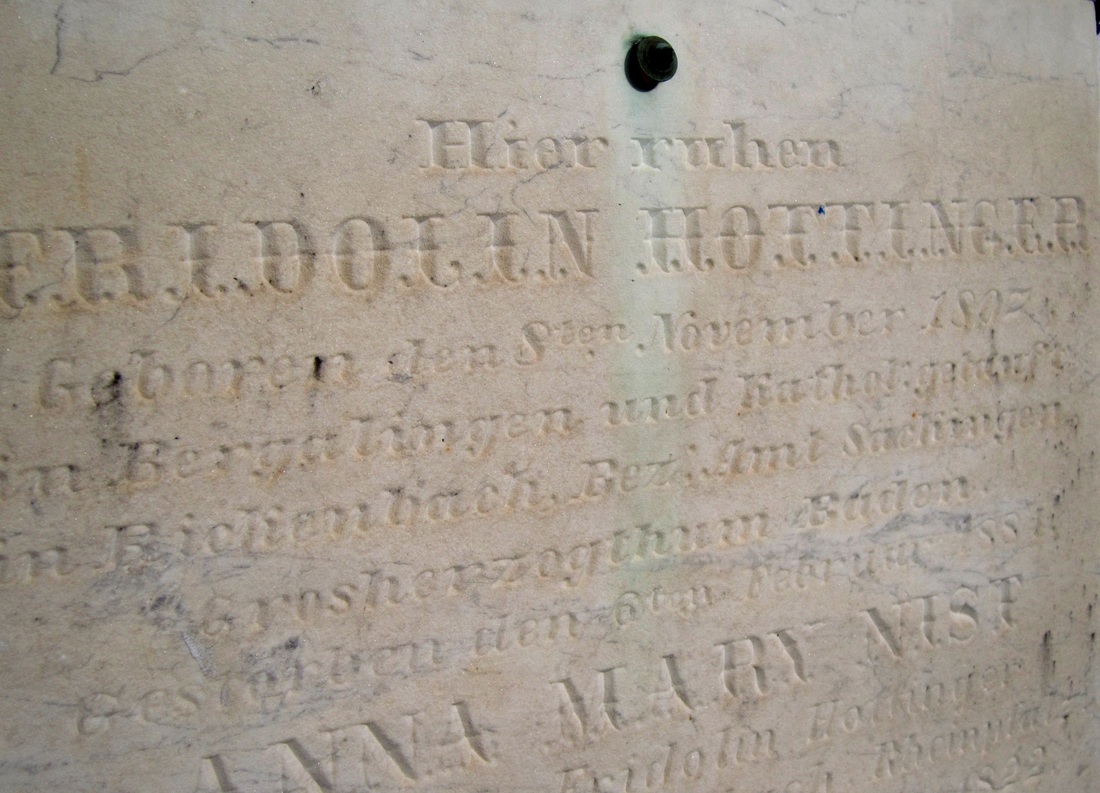

The address of H. Lowenstein’s business is recorded in directories and on his signed tablets as 195 and 197 Washington Avenue, which corresponds to the historic marble yard and shop located across Washington Avenue from Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. During the years Lowenstein held business there, other stonecutters and sextons advertised at the address, namely James Hagan and Philip Harty. Lowenstein also advertised himself as an undertaker at this address. Lowenstein’s carving style bears a resemblance to that of other contemporary German stonecutters, namely the Anthony Barret and his sons Charles and Frederick. These artisans carved in the German Fraktur style, or black-letter, and employed similar imagery of oak and laurel wreaths that are not found among the work of non-German craftsmen in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. These scant traces of Lowenstein in New Orleans indicate that he was likely a German-Jewish immigrant who served the community of the Fourth District, once part of the suburb of Lafayette. A number of German newspapers, including the Deutsche Zeitung and the Louisiana Straatszeitung, may have been the venue for his advertising. Considering he frequently carved closure tablets in German, it is likely that he aided more established craftsmen like Hagan and Harty with their business in the German immigrant community. Yet, after 1869, documentation of H. Lowenstein evaporates completely, suggesting that, like many other Jewish immigrants in the South, he may have moved elsewhere, or possibly died young in New Orleans.

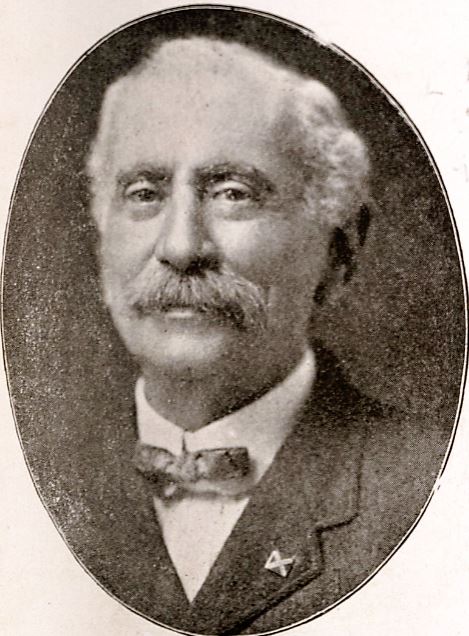

The business of Kursheedt & Bienvenu was among the most successful and prominent merchants of not only cemetery stonework and tombs but also hardware, commercial stonework, mantels, grates, and other items. By the 1880s, they owned not only a large show room on Camp Street but also a marble yard next door, at which at least thirty men were employed.

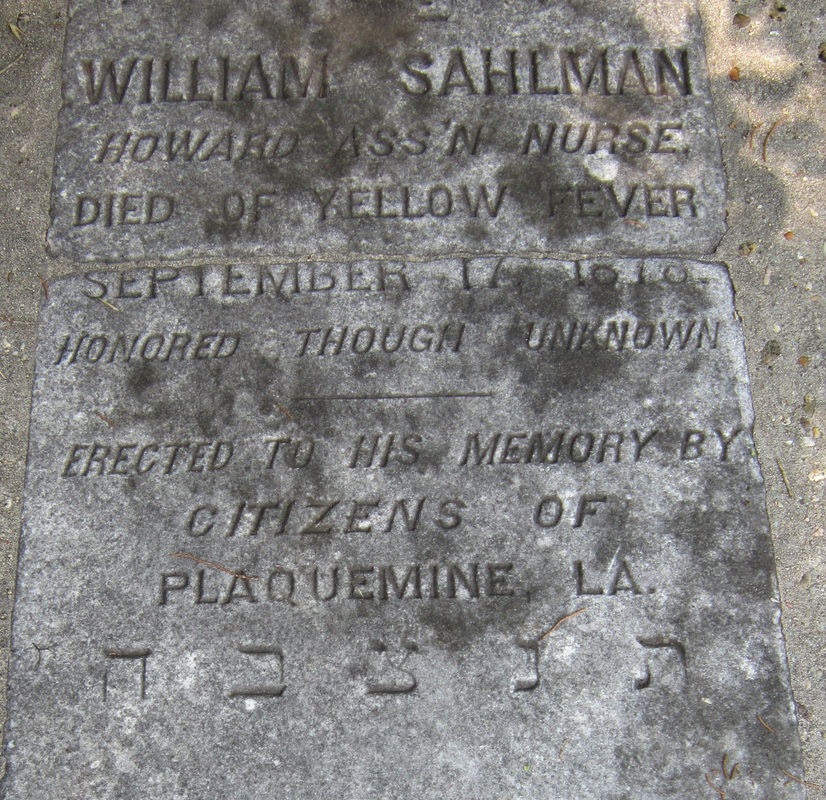

Much of Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s signed work can be found in Jewish cemeteries in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Alexandria, and Plaquemine, among other Louisiana towns. Within Jewish cemeteries, this work consists of headstones, as Jewish tradition prohibits above-ground burial. Yet Kursheedt & Bienvenu served clients of all religions and traditions. Among their most visible commissioned works is the Sercy tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Marked by a stone sarcophagus and located near the Washington Avenue cemetery gate, it is most notable for its epitaph: “Died of Yellow Fever,” a relic of the 1878 epidemic. J.G. Bienvenu left the business after 1888, and Edwin Kursheedt operated Kursheedt’s Marble Works until 1901.[8] Throughout these years, he served on various boards for Jewish Charities, including Touro Infirmary, the Hebrew Benevolent Association, and the Jewish Widows and Orphans Home.[9] He died in on February 21, 1906, at the age of sixty-seven, a veteran, merchant, benefactor, husband and father. He is buried in Dispersed of Judah Cemetery on Canal Street. It is unclear where or when H. Lowenstein died. The only tenuous hint points to an obituary published in the New Orleans Daily Picayune November 3, 1896, reporting the death of Henry Lowenstein, who died at the age of fifty-six in Cincinnati, Ohio. That a New Orleans newspaper reported his death suggests he once lived in the city, and may have been a young stonecarver on Washington Street in 1861, but no definitive documentation can support this possibility.[10] So these two artisans whose work is marked in New Orleans cemeteries died as they lived: one documented and memorialized, one lost in historic thin air, as were many immigrants who came and went from the Crescent City in the nineteenth century. [1] Bobbie Malone, “New Orleans Uptown Jewish Immigrants: The Community of Congregation Gates of Prayer,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 32, No. 3, Summer 1991, 239-287; Ellen C. Merrill, Germans of Louisiana (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2005), 225, 236.

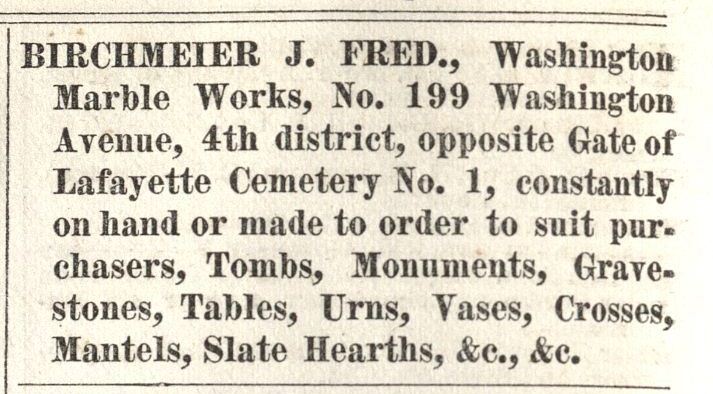

[2] The signature “Löwenstein” can be found on the Fridolin Hottinger tomb, Quadrant 2, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1861 (New Orleans: Charles Gardner, 1861), 282; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1866 (New Orleans: True Delta Book and Job Office, 1866), 279; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1869 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1868), 399. [3] Bertram Wallace Korn, The Early Jews of New Orleans (American Jewish Historical Society: 1969), 247-249; “Mr. Israel Baer Kursheedt,” The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, Vol. X, No. 3, June 1852, 1. [4] Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 111-116. [5] Andrew Morrison, The industries of New Orleans: her rank, resources, advantages, trade, commerce and manufactures, conditions of the past, present and future, representative industrial institutions, etc. (New Orleans: J.M. Elstner & Co., 1885), 144. [6] Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 21, 1880, 5; “The Other Side: The Report Adopted by the State-House Commission Respecting the Work Done,” Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 28, 1880. [7] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1887 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishers, 1887), 513. [8] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1889 (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1889), 532; Soards’ New Orleans City Directory, for 1901, Vol XXVIII (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1901), 501. [9] W.E. Myers, The Israelites of Louisiana: Their Religious, Civic, Charitable and Patriotic Life (New Orleans: W.E. Myers, 1904), 103. [10] Daily Picayune, November 3, 1896, 4. See also, Emily Ford and Barry Stiefel, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (History Press, 2012). Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. Full text here: http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/ The history of sextonship in New Orleans is as old as the city’s cemeteries. The origin of the cemetery sexton derived from European tradition, in which the sexton would care not only for the graveyard surrounding a church sanctuary, but also for the church itself. In New Orleans, the first sextons likely were part of a lay ministry, employed by the Catholic Church to care for St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and, later Saint Louis No. 2. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, however, was not administered by the Church or any other religious group. Instead, it was established in 1833 by the municipality of Lafayette, a suburb of New Orleans. Translating from the ecclesiastical to the secular sphere, the City of Lafayette employed a sexton to care for the cemetery at Washington Avenue and Prytania Street. From the cemetery’s founding into the 1950s, at least twenty-two individuals served as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Many were stonecutters and tomb builders, some were additionally undertakers, politicians, and masons. They cared for the cemetery in times of epidemic, vandalism, and population shifts. Through their stewardship, the landscape of the cemetery was formed. Phil Harty and the First Sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Up to and after the City of Lafayette was incorporated into the City of New Orleans in 1852, the role of the sexton was to perform and record interments, submit interment records to the city council, and maintain the cemetery grounds. It was also his responsibility to enforce the ordinances of the city and state regarding interments and sanitary conditions.[1] These laws included the collection of a certificate of burial (presented by a physician or coroner to the deceased’s family), ensuring the deceased was properly placed in a coffin, and construction regulations regarding tombs. Failure to perform these duties resulted in punishment from City Council.[2] Sextons were additionally paid a fee for each interment based on the deceased’s status as colored or white, child or adult, and whether the interment was to be an act of charity. In the nineteenth century, these fees varied from 50 cents to $1.50, with a $3.00 charge for the opening and closing of tombs and vaults, to be paid by the owner.[3] The first sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was most likely B.S. Quinman, who served from 1832 to 1844.[4] After Quinman, H.G. Hicks served briefly in the position. While many sextons constructed tombs in Lafayette No. 1, no structure or tablet in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 bears either man’s signature. Their successor, however, seems to have made more of an impact on the cemetery. Philip Harty, mostly referred to in documentation as Phil Harty, served as Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 sexton from 1855 to 1861. [5] Only one of his signed works survive amidst the rows and aisles of tombs: the tomb of A. Thomas, located near the rear gate.[6] He lived at 197 Washington Street, across from the main gate of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. This address was utilized by numerous sextons and stonecutters throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Today, the lot is listed as 1427 Washington Avenue. The building is currently utilized as the administrative offices for Commander’s Palace restaurant. Phil Harty died August 14, 1861. His obituary, describing his death as “sudden,” states that Harty was well-known as a sexton and a “hearty, merry fellow up to the very hour of his death. Thousands he has introduced to the narrow house, and now he has gone himself, with scarcely a moment’s warning.”[7] D.F. Simpson, a local stonecutter, followed Harty as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1863 to 1868. He was also a stonecutter and tomb builder – his office was located on Race Street.[8] Examples of his work remain in the cemetery today, including the Stearns tomb and at least three constructed while Simpson was in business with later sexton J. Frederick Birchmeier. Following D.F. Simpson were James Hagan (1830-1908, sexton 1865-1867), and Joseph F. Callico (sexton 1867-1875).[9] James Hagan served as state senator representing Orleans Parish from 1880 to 1884. Based on remaining signed tombs and closure tablets, J.F. Callico was one of the most prolific stonecutters among the sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1: today, nearly thirty tablets in the cemetery bear his signature. 1865 – 1900: A Thriving Craft Community The late 1870s were unusual for the stewards of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in that no one individual served for more than a few years. As had occurred in previous years, especially 1853, yellow fever epidemics were particularly difficult times for sextons. It is possible, then, that the 1878 epidemic, the marks of which are still very visible on the tombs and tablets of Lafayette No. 1, caused an upset in the administration of the cemetery. In quick succession, Dennis Irvin, Cornelius Donovan, John Barret and Patrick Gallagher served as sextons from 1876 to 1880. Patrick Gallagher likely left his office due to accusations against him that he attempted blackmail on an unnamed person.[10] After these men, J. Frederick Birchmeier, a stonecutter who had been active in Lafayette No. 1 for decades, became sexton.[11]

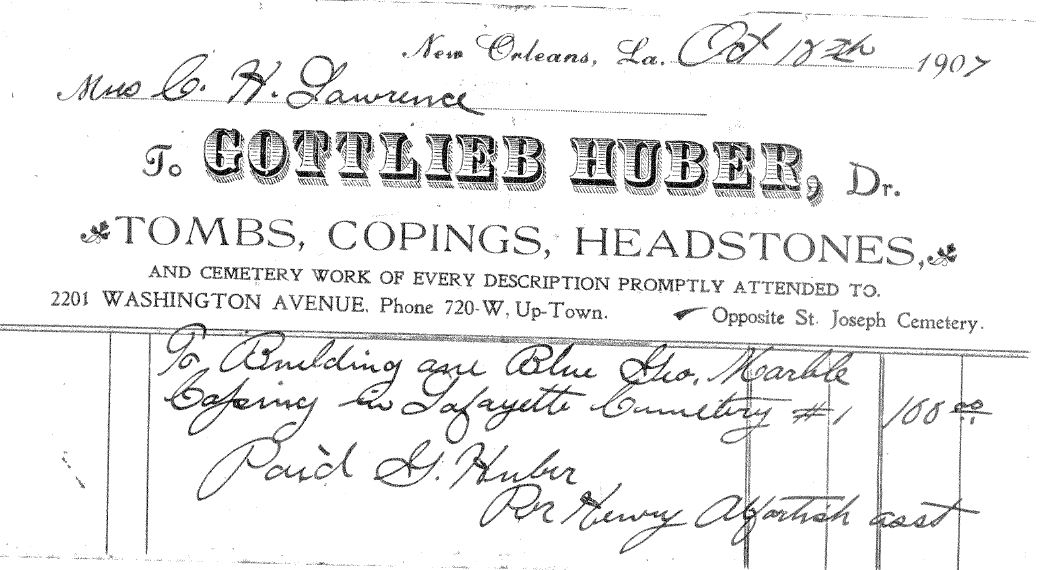

The turn of the twentieth century brought to Lafayette No. 1 a close-knit community of stonecutters and tomb builders, many of whom served as sextons. After J. Frederick Birchmeier retired, his colleague Hugh J. McDonald (1853-1895, sexton 1886-1895) took over stewardship of the cemetery. After McDonald’s death, stonecutter Charles Badger succeeded him. Badger was also the husband of Birchmeier’s daughter, Margaret.[14] Both Badger and McDonald were close colleagues of Gottlieb Huber, who was sexton from 1902 to 1915. The legacy of this community would continue for the next thirty years through another young protégée of these men. 1900 – 1945: The Alfortishes In 1911, Henry Alfortish became assistant to Gottlieb Huber at Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Alfortish also worked with Huber privately, and would absorb Huber’s business after his death in 1926.[15] The influence of Alfortish and, later, his son Edward, would greatly change the cemetery. In the 1920s, Alfortish declared numerous lots abandoned and “open for sale.” He sold these lots and tombs to new clients and, additionally, provided replacement deeds for families who had lost their tomb ownership documents. It was also under the sextonship of Henry Alfortish that the wall vaults once located along Sixth Street were cleared and demolished. Numerous coping tombs located along this wall today bear Alfortish’s signature.[16] Edward Alfortish assumed sextonship of Lafayette No. 1 in 1942. However, the role of sexton was no longer seen as relevant in the city-owned cemetery. Few burials were made compared to the heyday of Lafayette No. 1, and many of the responsibilities of sexton could be carried out by other city officials. By around 1950, no individual would serve as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 again. The caretakers of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1833 to 1950, built the cemetery as it is seen today. They designed and constructed its tombs, removed and replaced landscape features, fostered its dead and their families, and protected the cemetery from harm. Their names are placed alongside the names of Lafayette No. 1’s most famous residents, in the form of carved signatures at the bases of closure tablets and headstones. The story of this National Historic Landmark cemetery is very much their story. [1] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4; State of Louisiana, The Revised Statutes of Louisiana (J. Claiborne, 1853), 386.

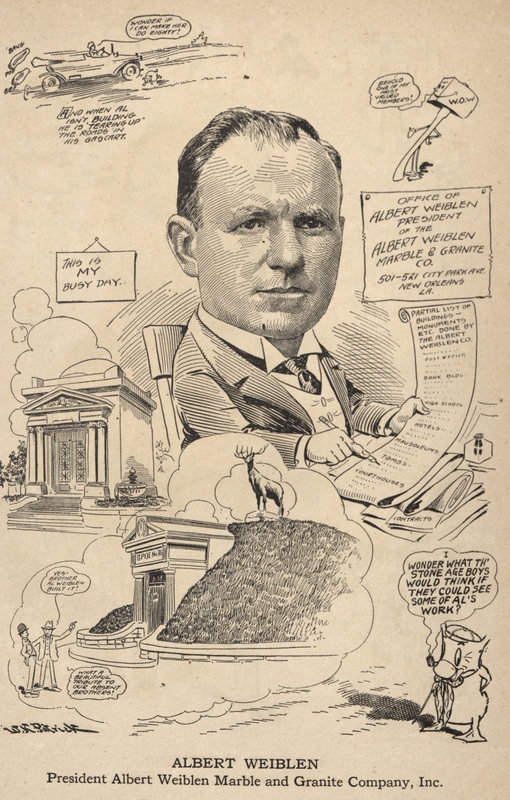

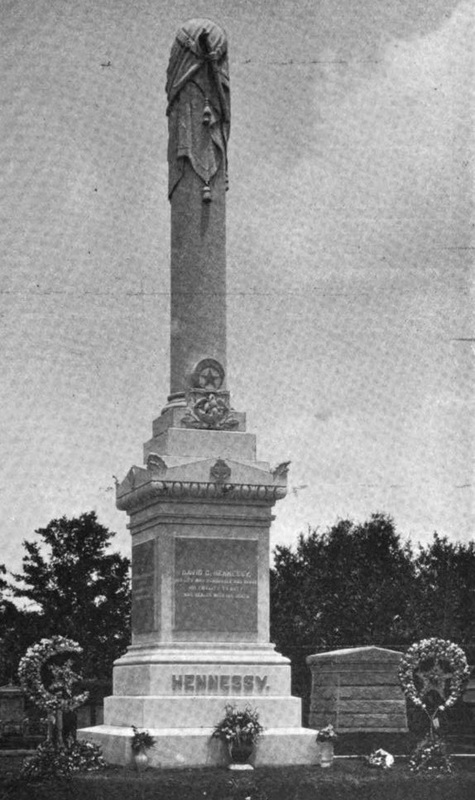

[2] “City Intelligence: Board of Health,” Daily Picayune, August 4, 1853, 1. [3] Ibid.; Currency evaluation oriented around historic standards of living, these costs equate to approximately $20-$40 per interment and $81 (2011 dollars) for the opening/closing of a tomb or vault. (www.measuringworth.com) [4] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84 (Baton Rouge: Leon Jastremski, 1884), 40. [5] Daily Picayune, February 15, 1855, 6; Mygatt & Co.’s Directory for New Orleans, 1857, W.H. Rainey Compiler. L. Pessou & B. Simon Lithographers, 23 Royal Street, New Orleans, 1857, 49; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for the Year 1859 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1858), 377; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1860 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1859), xvi. [6] Based on a 2012 survey of all signed craftwork in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. The Isaac Bogart tomb, located in Quadrant Three of Lafayette No. 1, is documented in the 1981 Save Our Cemeteries/Historic New Orleans Collection Survey of Historic Cemeteries as having a tablet signed by Phil Harty. The tablet has since been lost. [7] “Sudden Death,” Daily True Delta, August 15, 1861, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 18, 1866, 3. [9] Based on directories and municipal documents. [10] “An Official Suspended,” Daily Picayune, October 9, 1878, page 2. [11] Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1880 (New Orleans: L. Soard’s Publishing Co., 1880), 456; Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1882 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1882), 142; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1883 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1883), 452. [12] “A Singular Case,” Daily Picayune, June 14, 1868. [13] Receipt from J. Frederick Birchmeier to the widow of John Paul, Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 365. [14] Daily Picayune, February 8, 1891, 1. [15] Times-Picayune, January 20, 1926, 2. [16] Receipts for lots Quadrant Three, Lots 16 and 17, Quadrant 1, Lots 270-275, the Moulin, Gonea, Legien, and Bittenbring tombs. Sexton’s book, page 127. Historic New Orleans Collection, Leonard Victor Huber Collection, MSS 365. On May 1, 1957, and only a few months shy of his 100th birthday, Albert Weiblen passed away in New Orleans. In his lifetime, Albert Weiblen was a revolutionary figure in New Orleans cemetery architecture. Under his carving hand, the craft of tomb building would expand from a hyper-local, individual cottage profession into a modern industry – spanning the eastern United States and powerfully altering the landscape of New Orleans cemeteries. A German Immigrant in New Orleans Albert Weiblen was born in 1857 in Metzingen, Wurttemberg, Germany. Sources suggest that he began his work as a sculptor in his homeland, apprenticing in the manner that was traditional for the time.[1] Weiblen immigrated to the United States in 1883 and soon afterward began work with local marble company Kursheedt and Bienvenu. Operational from 1867 to 1901, the company was co-owned by Edwin I. Kursheedt, a prolific stonecutter in his own right who, in addition to work in New Orleans’ Jewish cemeteries and other cemetery stonework, supplied the stone for the reconstruction of the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the late 1880s.[2] At this time, New Orleans’ cemetery stonecutting industry was already changing. The florid, individualized Classical-revival tombs popular from the 1840s through the 1860s had given way not only to new styles inspired by Gothic and Italianate revival aesthetics, but also to economies of scale. The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878 galvanized this trend. In this year, the construction of tombs shifted more to “cookie cutter” and slightly simplified styles, replicated by numerous carvers and builders.[3] Weiblen stepped into the cemetery craft scene in New Orleans at a time when this streamlining of tomb construction was in its infancy. New industrial technology, such as saws and machinery to cut granite and marble, new types of stronger hydraulic cements, and stonecutting technology powered by pneumatic chisels and even sandblasting, had been adopted elsewhere in the country, but were a long way off from making their debut in New Orleans cemeteries.[4] When these new tools and methods did arrive, though, it was often Weiblen who spearheaded their use. In 1887, Weiblen left Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s and started his own marble and granite company.[5] His first office and show room was located at 233 Baronne Street, a location he expanded by 1893.[6] Weiblen’s big break came in 1891 when his company won the contract to construct the memorial obelisk to New Orleans Superintendent of Police David Hennessy. Hennessy was murdered on October 15, 1890, an event which sparked riots in New Orleans and led to the lynching of eleven Italian-Americans. The contest had been open to many New Orleans monument men, including Charles A. Orleans, the city’s prominent monument builder at the time.[7] The monument was described by national trade periodical Stone magazine as “one of the handsomest monuments in New Orleans”: