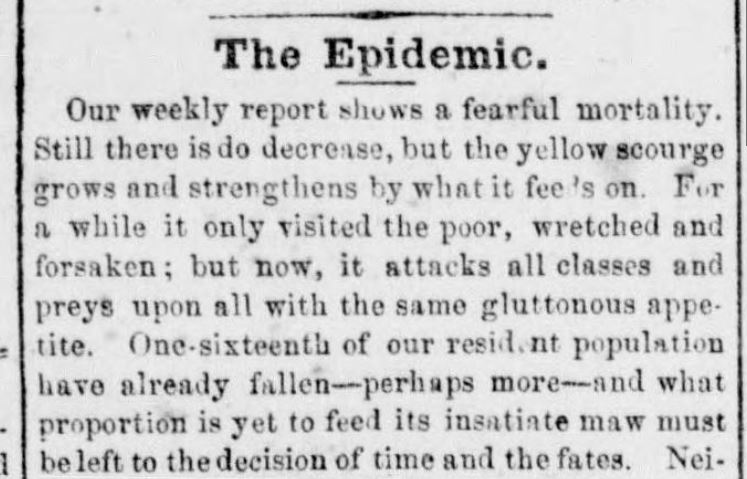

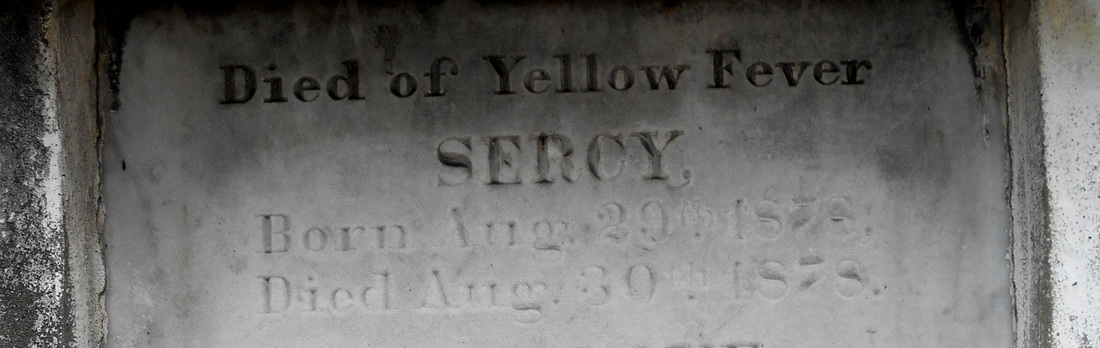

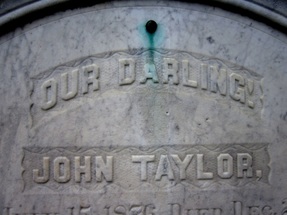

Detail of closure tablet for John Taylor, infant victim of 1878 Yellow Fever epidemic, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Photograph by Emily Ford. Detail of closure tablet for John Taylor, infant victim of 1878 Yellow Fever epidemic, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Photograph by Emily Ford. Yellow Jack, the Saffron Scourge, Bronze John: Yellow fever was a chronic fear, a “fearful ravage” in New Orleans from the time of its founding through the first years of the twentieth century. We often see remnants of the great sweeping epidemics of 1853, 1866, 1878, and other years carved in the stone of our cemeteries. While the silent presence of dozens of July, August, and September death dates that surround one in any corner of a New Orleans cemetery can be striking, the yellow plague carved even more drastic elements into the landscape. Entire sections of cemeteries re-developed by stonecutters and tomb builders to accommodate the incoming deceased are lost to our eye by modification and decay. The “Yellow Fever Mound,” a section of Girod Street Cemetery, was lost altogether with the demolition of that cemetery in 1957.[1] The role of sextons[2], stonecutters and tomb builders in this time was grim. In the summer “sickly season,” when all those who could afford to left the city for drier, cooler climbs, these craftsmen and caretakers were obligated to remain and make their trade available. This meant much more than building tombs as quickly as possible – since many stonecutters were sextons themselves, it meant managing the overwhelming presence of deceased bodies, many of which had no tomb or lot into which they could be interred. In some cases, victims were interred of by way of mass grave. In many more cemeteries beyond Girod, laborers were hired to dig long rows for the burial of simple donated caskets, covered up with small mounds of earth. In other cases, charities could accommodate the cost of burial in wall vaults. Often, families lent the use of their private tombs to friends with deceased spouses or children.

For further reading:

Benjamin H. Trask, Fearful Ravages: Yellow Fever in New Orleans, 1796-1905. Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2005. Jo Ann Carrigan, The Saffron Scourge: A History of Yellow Fever in Louisiana, 1796-1905. Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1994. [1] Huber, Leonard Victor, and Guy F. Bernard, To Glorious Immortality, The Rise and Fall of Girod Street Cemetery, New Orleans’ First Protestant Cemetery, Alblen Books, 1961, 9. [2] Officially-appointed cemetery caretakers. This role originated with church vicars and later extended to municipal, church, and fraternally-appointed positions. [3] New Orleans Public Library, http://nutrias.org/guides/genguide/burialrecords.htm [4] The “Bayou Cemetery” potter’s field was established in 1835; while many references suggest the site was redeveloped and became St. Louis Cemetery No. 3, some sources suggest the site of the cemetery to have been elsewhere. [5] Bennett Dowler, M.D., “Tableaux, Geographical, Commercial, Geological and Sanitary of New Orleans,” printed in Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1852 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1852): 19-20. [6] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” New Orleans Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4. [7] “History and Incidents of the Plague in New Orleans,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7, Issue 39 (August 1853), 800. [8] “The Fever,” Daily Picayune, July 30, 1853, 2.

0 Comments

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly