|

New Orleans is home to dozens of cemeteries, each with its own character and history. Among these many burial and interment grounds are the influences of world cultures, human expressions of grief, and iterations of architecture that, in one way or another, are recognized as significant on small and large scales. Some are more appreciated than others. Some have been lost entirely from the landscape, such as St. Peter Street Cemetery, Girod Street Cemetery, or Gates of Prayer Cemetery on Jackson Avenue. Yet among these recognized and unrecognized burial grounds, there is one nearly always omitted, even though people walk by it and photograph it every day. Tucked behind St. Louis Cathedral and often overshadowed by the looming statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, is the final resting place of nineteen French navy men who died in 1857 and were re-interred at this place in 1914.

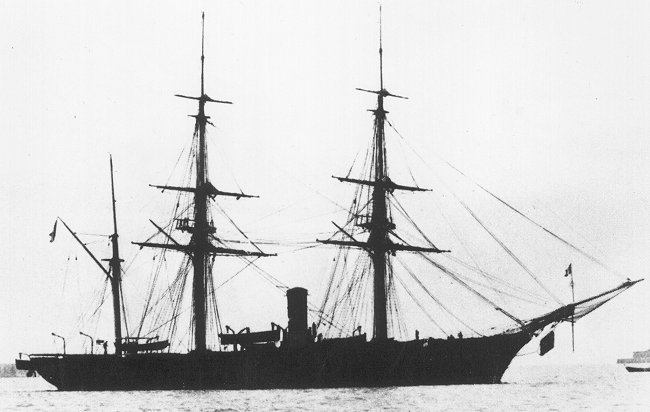

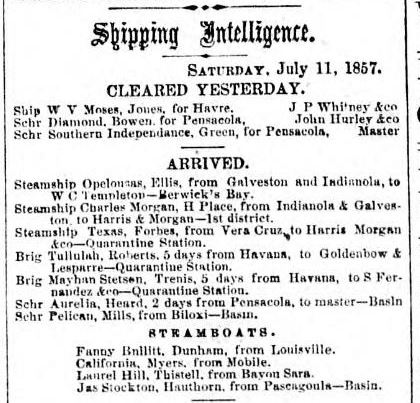

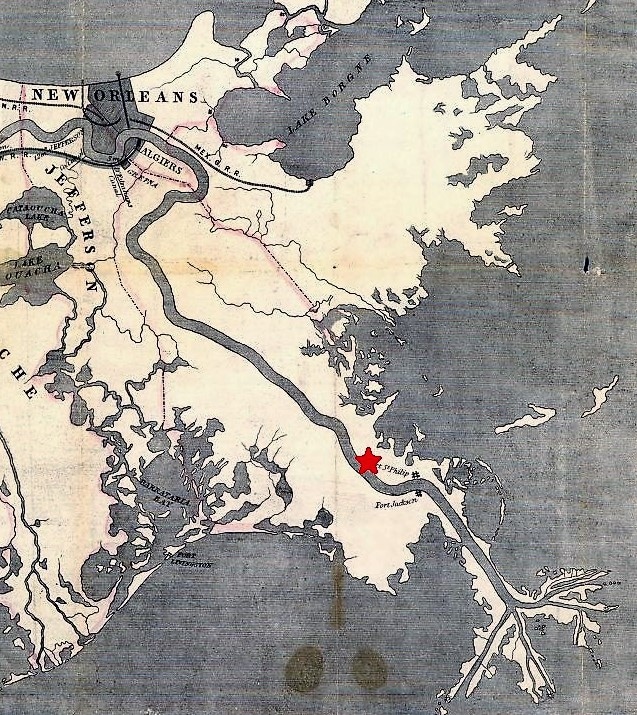

In the years following this harrowing incident, the surviving crew of the Tonnerre and their families in France, as well as French naval authorities, sought to memorialize the lost sailors. A monument was erected in the Quarantine Station cemetery in August 1859. The marble obelisk would not be seen for long, however. The Quarantine Station was soon relocated, with the former site abandoned. The monument would not be rediscovered until 1914, when Andre Lafargue endeavored to reclaim it.[3] The tale of the Tonnerre, its crew, and its monument, highlights so many historical aspects of the mid-nineteenth Caribbean and Atlantic world. It is a story of memorialization and reclamation, of the interactions between cultures and nations, and of the management of public health in this time. In this post, we seek to unpack some of these curious aspects of the monument that rises so subtly from behind St. Louis Cathedral. The Ship Tonnerre The Tonnerre is referred to in historical documents as both a corvette and an aviso or “advice ship.” While there appears to be some distinction between the two (and we don’t presume to call ourselves naval historians) – for example, avisos are customarily smaller than corvettes – documents consistently refer to the Tonnerre as a ship assigned the duty of relaying messages between larger naval commands. The four-gun Tonnerre was a steam-powered vessel, propelled by a paddle, and was inducted into service by the French Navy at Indret in 1838.[4] By 1850, the French Navy had about a dozen such first class “advice boats,” including five constructed of iron (Le Mouette, Le Heron, Le Eclaireur, Le Requin, and L’Epervier), although the Tonnerre was not constructed of iron. By 1857, the Tonnerre and its crew had already completed service in the Crimean War (1853-1856) in which an alliance of European powers fought Russia for influence over the Black Sea and Middle Eastern. Lieutenant Clement Maudet, who came to command the Tonnerre, fought with the French Foreign Legion in Crimea, earning a medal for his bravery. Many of the other sailors aboard the Tonnerre served in this conflict before being dispatched to the Caribbean. The presence of the Tonnerre in the Caribbean also highlights the colonial and military interactions in the Caribbean and Atlantic world at the time. The Tonnerre was charged with relaying messages between Vera Cruz and Havana (a role the ship would serve through the late 1850s).[5] The ship’s mission likely related to French economic and political interests in Mexico, which Emperor Napoleon III viewed as critical to Latin American trade access. French intervention would escalate to full on invasion in 1861, and later the unsuccessful installation of Hapsburg emperor Maximilian I. It was in this conflict in 1863, that Lieutenant Clement Maudet would die of wounds acquired in the Battle of Camerone.[6] The Tonnerre was the fifth ship of the French navy to bear this name. The first French Naval Tonnerre was the British HMS Thunder, captured in 1696. The Tonnerre under Maudet’s command in 1857 was retired in 1878. The French Navy currently operates the eighth Tonnerre, placed into active service in 2006. The Crew The Tonnerre had an original crew of eighty sailors, including a doctor (who died of yellow fever at the Quarantine Station), sailors, ensigns, stokers (steam engine operators), chefs, and mates. Eighty of whom contracted yellow fever either in Mexico, Louisiana, or Cuba. Thirty of these seamen died. Two of the chefs aboard the Tonnerre who perished in 1857 appear to have been of Italian descent: Giovanni Carletto and Jean Janotti. Ages of the men who died aboard the Tonnerre are not listed.

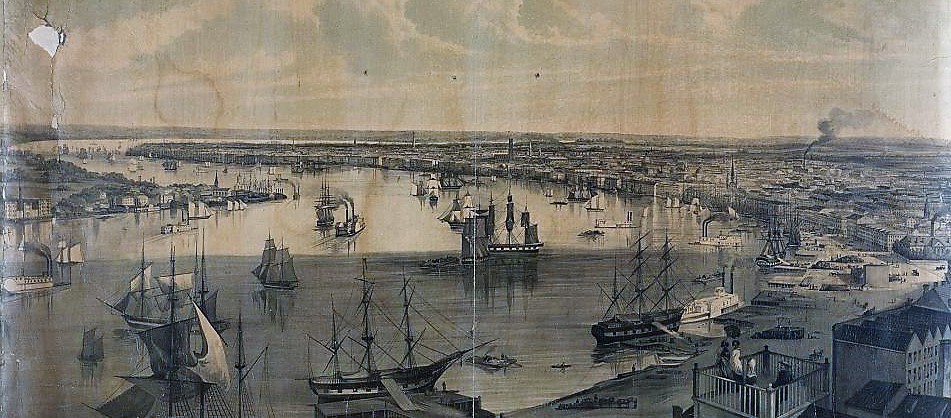

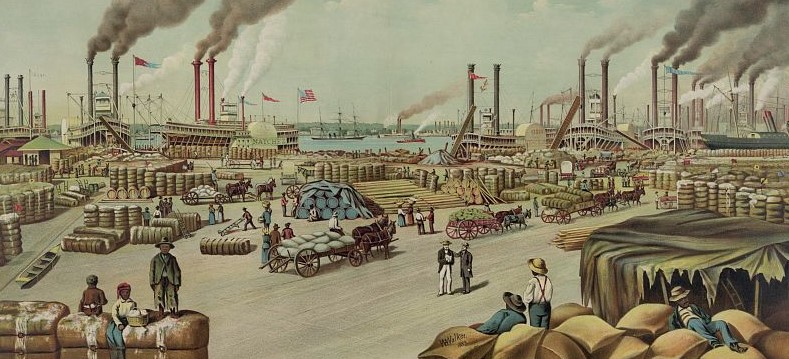

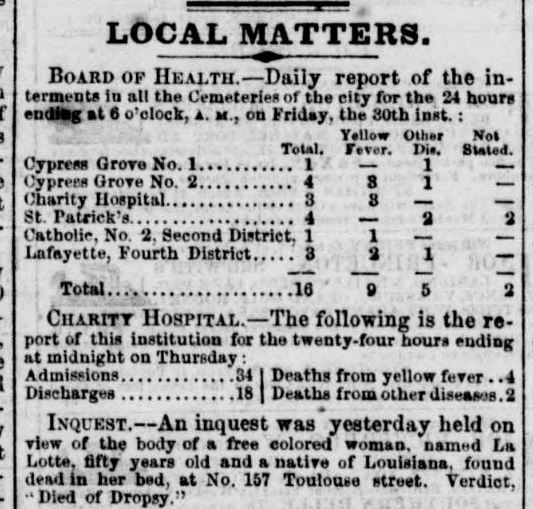

In 1853, for example, the fever was presumed to be caused by “miasmas” or “bad air” (a theory derived from Enlightenment thought), and thus the City burned torches of pitch and discharged cannons in order to disperse airborne maladies. By the 1850s, the Sanitarian movement had begun to marginally influence public health, focusing on cleanliness of public spaces and the removal of fetid water. Quarantine Stations were present in most eastern seaboard cities by the early 1800s. In New Orleans, the necessity of such stations was frequently debated and they were often decommissioned. In many cases, New Orleans merchants were staunch opponents of quarantine. Such systems, they said, disrupted commerce and were thus unacceptable. Their arguments appeared validated when, on occasion, epidemics broke out despite the presence of quarantine stations – likely due to the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti)’s fondness for sheltering in ship cargo holds. Incidentally, however, 1857 was not a significant epidemic year for New Orleans. As the Tonnerre had no intention of docking in the City en route to Havana, the condition of this one ship’s crew posed little danger of epidemic to the Crescent City.

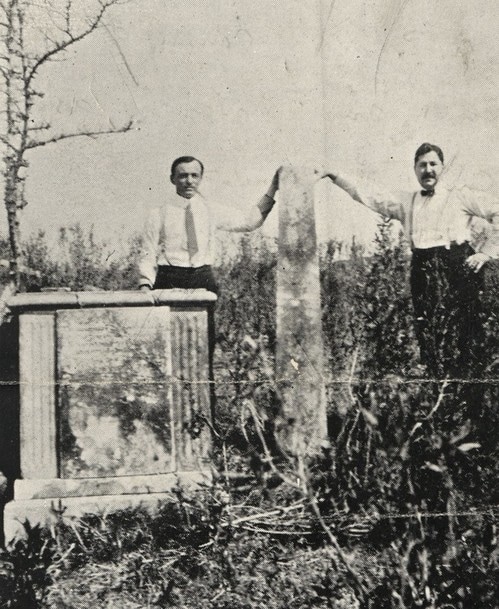

The Quarantine Station would be abandoned after the 1860s, after the US Government established an additional Quarantine Station at Ship Island, Mississippi. In 1880, the Louisiana Board of Health reported on the condition of the Ostrica-area Station, the grounds “open and roamed over by cattle.[10]” It described a complex of several buildings: a fever hospital, a pox hospital, a medical residence, a boatmen’s quarters, and a warehouse. Said the board of the process of disinfection at the hospitals: The process of disinfection now employed consists of burning sulphur in iron pots. These pots are placed in tubs containing water. This method is liable to the grave objection that there is, in many cases, and especially during rough weather, danger of firing the ship.[11] In this report, the Board of Health appears to be investigating the feasibility of placing the Station back into service, although no evidence suggests this happened. However, the report documented the enduring presence of the Tonnerre monument: The graveyard of the Quarantine Station is located about 200 feet to the rear of the Fever Hospital, and is surrounded by a rude fence and covers about three-fourths of an acre. Marks of about one-hundred graves can be discerned by the inclosure [sic], which are thickly covered with tall grass, brambles, and shrubs. There is only a solitary marble monument, which bears the following inscription: "A la mémoire de Trente Marins, faisant partie de l'équipage de l'avito vaisseau de la Marine Imperiale le Tonnerre, décède à la Quarantaine de la Nouvelle Orléans en Août, 1857. Erige par l'Odre de S.E. L'amiral Hamelin, ministre de la Marine de l'Empereur Napoléon III.”[12] The Monument Thanks to donations from the families of surviving Tonnerre crewmen, a marble monument was installed at the Quarantine Station in 1859. Unfortunately, the craftsperson that designed and built it is unknown. Photos from the monument’s recovery indicate that it was originally a marble-clad box tomb, with fluted corner pieces and a marble slab atop which the monument’s obelisk and urn were fixed. This style of memorial was typical of 1850s high-style cemetery architecture in both New Orleans and France. Derived from sarcophagus designs, similar monuments can be found in the cemeteries of Montparnasse (France) and St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, although less modified versions are visible in the upriver parishes. The Tonnerre monument was described intact by the Louisiana Board of Health in 1880, even though the Quarantine Station cemetery had become derelict. Andre Lafargue shares a similar recollection from his youth, seeing the monument ascending from the brush as he traveled the river. Lafargue notes that at some time between 1880 and 1914 the obelisk fell in a hurricane.[13] The Quarantine Station long abandoned, without intervention the Tonnerre monument would have sunken beneath overgrowth and debris. Yet in 1914, Andre Lafargue, who at that time served as the attorney for the Comité du Souvenir Francais, came across in the French Society records documentation of the Tonnerre monument. In an effort that proved fruitful if not also tremendous and risky, Lafargue chartered a boat from Buras to Ostrica, bringing with him the vice French consul general at the time, Andre Lacaze, and their wives.[14] Trudging through the brush with only a vague recollection of where the cemetery and Quarantine Station once stood, the party discovered the remains of the monument: We finally came to a spot, near a tree of greater dimensions than the others, and there found traces of former habitations, and all of a sudden our feet struck a pile of bricks and pieces of marble and we knew, after examination of the fragments, that we had finally found the spot where the cemetery stood long years before and where the monument had been built. The ladies, highly elated by the discovery, were very helpful in picking up various pieces of the pedestal and we finally located the obelisk, the main section of the most important part of the monument, and the gracefully draped urn. The urn had been wrenched from the top of the obelisk and the latter had broken into two pieces in its fall to the ground, after the pedestal and the foundation had been undermined by the elements and the rough usage of time.[15] Over the course of subsequent trips to the site and through partnerships with groups like the Societe de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle, the monument was packed away and sent upriver to New Orleans. Despite the contestations of local undertakers that recovery of the remains of the 19 seamen who died at the Quarantine Station would be impossible, Lafargue and his crew set out to disinter each one. Each body was laid beneath the flag of France during disinterment, then shrouded and placed together in a metallic casket, where a single French flag was draped across them. In an additional gesture of reverence, the party uprooted a small tree from the cemetery and placed it in the coffin with the remains, to be re-planted at the new monument site.[16] The monument was reconstructed by New Orleans stonecutter and tomb builder Albert Weiblen. Weiblen built a burial vault atop which the monument would sit and bordered with a Georgia Creole marble coping wall. This vault forms a tumulus structure and simultaneously elevates the monument. Weiblen’s skill in reconstructing the monument is remarkably evident: it is difficult to determine which elements of the monument are replacements and which are original. But some clues are visible: one inscribed tablet is of a slightly different type of marble, and is inscribed with a pneumatic tool, whereas the other inscribed faces of the pedestal have smaller, hand-carved lettering. It appears as if the monument itself may have been slightly downsized, it’s dimensions shaved away to remove damaged or unsalvageable elements. A small bronze plaque was installed at the front of the coping by De Lucas Monument Company at the cost of $13.[17] Since its rededication, the Tonnerre monument has survived a few more hurricanes, and an instance in the 1930s in which an inebriated driver crashed through the gates of the Cathedral garden and toppled the obelisk. But for the most part the monument (and the remains therein) have known peaceful repose, quietly situated between St. Louis Cathedral and Royal Street, so often escaping notice. [1] Andre Lafargue, “The Little Obelisk in the Cathedral Square in New Orleans,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan. 1945), 329.

[2] Every history of the Tonnerre’s trials at the Louisiana quarantine station omits the commander’s first name. Based on other histories of the French Navy in the Baltic and Mexico, and other statistical data, the commander of the Tonnerre was most likely Clement Maudet (1829-1863), French Legionnaire, who would die later in Mexico during the Battle of Camarone, part of the Second French Intervention. [3] Ibid., 333-336. [4] John Fincham, A History of Naval Architecture, to which is prefixed an introductory dissertation on the application of mathematical science to the art of naval construction (London: Whittaker and Co., 1851), 408. [5] French war steamer Tonnerre embarks from Havana to Mexico, Daily Picayune, October 21, 1857; French war steamer Tonnerre returns to Havana, Daily Picayune, December 14, 1857. [6] This is an extremely generalized recapitulation of colonialism in the Caribbean in the 1850s. For further reading see: The Second French Intervention in Mexico, The French Intervention in Mexico and the American Civil War, and if all of this is too complicated or frustrating, just check out this fun comic. [7] Henry Rightor, Standard History of New Orleans, Louisiana (New Orleans: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900), 211-213. [8] John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 60; Joy J. Jackson, Where the River Runs Deep: The Story of a Mississippi River Pilot (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1993), 55; Alcee Fortier, Louisiana: Comprising Sketches of Parishes, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form, Vol. 2 (Century Historical Association, 1914), 337. Jackson notes quarantine stations located at Cubit’s Gap (around 1910) and a post-1920 station at the lower end of Algiers. Andre Lafargue describes a quarantine station at Pilot Town, twenty miles downriver from Ostrica, by 1914. [9] John Duffy, ed. The Rudolph Matas History of Medicine in Louisiana, Vol. II (Binghamton, New York: Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., 1962), 185-186. [10] Joseph Jones, M.D. Report of the President of the Board of Health of the State of Louisiana for the Year 1880, 14. The report also notes the success of quarantine measures for that year, including the removal of the bark Excelsior, bound from Rio de Janiero, to Quarantine, which “certainly freed the city of New Orleans from the infected crew, and in the opinion of a portion of at least of the medical profession, preserved the citizens from an epidemic.” [11] Ibid., 18. [12] Ibid., 15. [13] Andre Lafargue, “The Little Obelisk in the Cathedral Square in New Orleans,” 336. [14] John Smith Kendall, A.M., History of New Orleans, Vol. III (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1922), 1149. [15] Ibid., 338. [16] Ibid., 336-342. There is no indication that this tree remains in the garden behind St. Louis Cathedral. [17] Receipt from De Lucas Monument company to Comite Francaise, Andre Lafargue papers, MSS 552, Folder 10, Tulane Louisiana Research Collection.

5 Comments

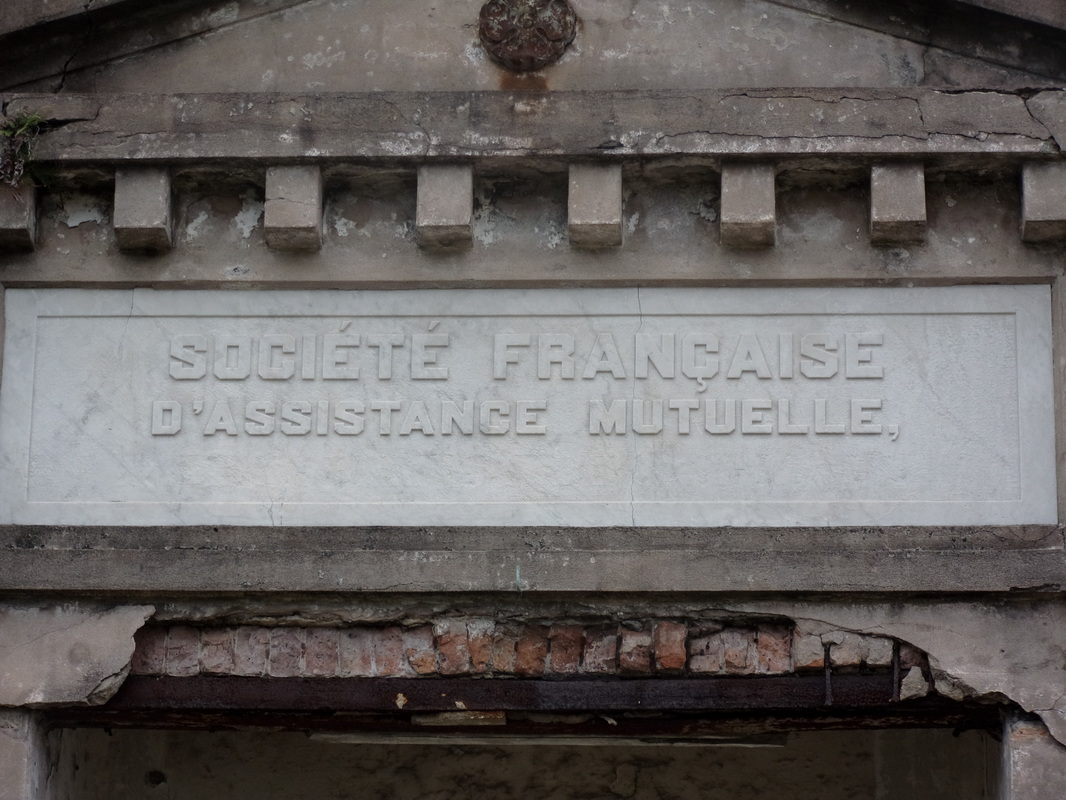

This blog post is Part Two of a two-part piece on the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. To learn about the history of this French Society, check out Part One here. Recently, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC transcribed the burial records of the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, thanks in part to a grant from genealogist Megan Smolenyak. The Society was absorbed by the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans in 1900. About the Record Books The records of the Sociètè are housed at LSU Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, in Baton Rouge. (MSS 318, 1012) The burial books appear to have been included with the larger collection of papers from the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (French Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society of New Orleans) which absorbed its Jefferson City counterpart in 1900. The collection is comprised of two books, dating from the tomb’s construction in 1872 through 1900. While later interments were certainly made in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb, their record appears to have been incorporated into another, as-yet unstudied document. Within these two books are the burial documents for 186 individuals. Among these records, 142 people were buried in the society tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, 32 were provided formal burial aid by the society and were interred in family tombs throughout the city, and 12 were not specified as to burial location.[1] Each burial record documents the date and place of the individual’s birth, date and place of death, as well as cause of death and information regarding membership. These documents shed light on the lives of hundreds of people. They allude to intricate familial and professional relationships, personal tragedies, and public calamities. They offer a window into a rich community, the vestiges of which stand silent in this stately yet neglected tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Today we share the stories of those buried within. The Foreign French: Founding Members and their Origins The Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson was organized in 1868 by native-born French men – eight of whom are buried in the Lafayette No. 2 tomb. Much like the New Orleans French society, these immigrants sought fraternity among their countrymen. Incidentally (or perhaps not so much so), most of these men were born in the same French provinces (départments), and often in the same village. The majority of adults buried in the Sociètè tomb originated from two primary areas in continental France: the department now known as Midi-Pyrenees, including Gers, Haute-Pyrenees, Haute-Garonne, and Bass Pyrenees (now known as Pyrenees-Atlantiques), and the eastern departments of Alsace-Lorraine, specifically Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin, and Moselle. These two areas are nearly as geographically disparate as can be, with the former nestled along the Pyrenees mountains at the Spanish border, and the latter at the Rhine River beside present-day Germany.

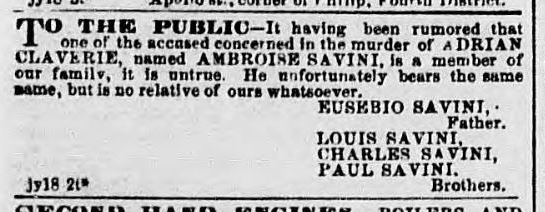

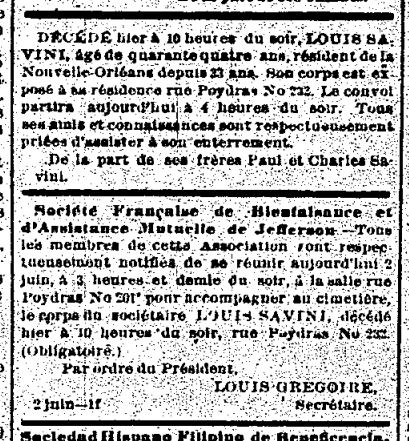

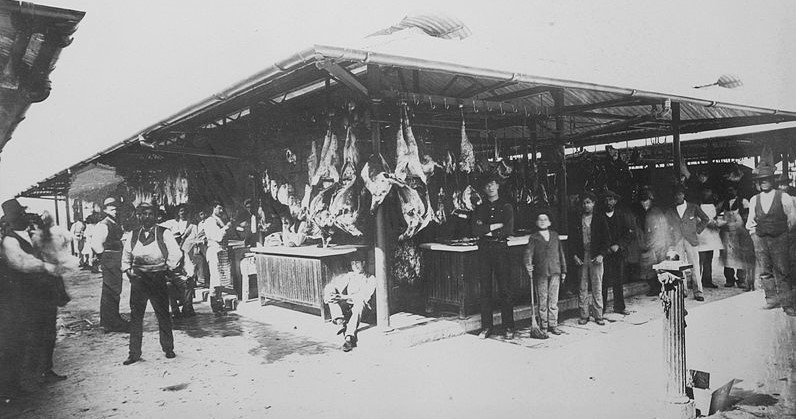

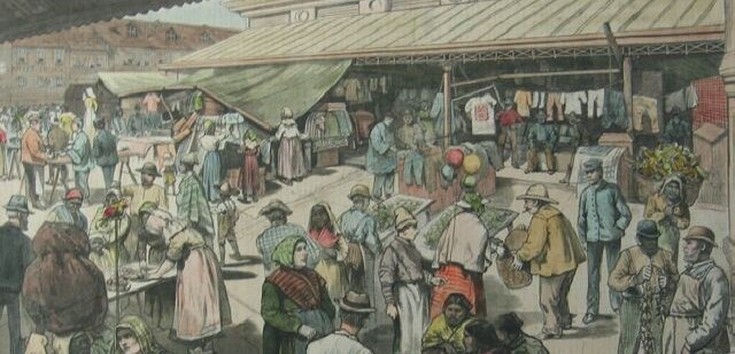

In Alsace-Lorraine, a different climate motivated the eventual members of the Sociètè to emigrate from their homes. The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) forced many Alsatians from their homeland when the controls of the provinces shifted from France to newly-nationalized Germany. For French-speaking Alsatians, both Jewish and gentile, German citizenship was a less than desirable option. New Orleans was an attractive alternative due to its Francophone tradition. Among these Alsatian emigrants were sisters Catherine and Marie Sonntag, both in their early twenties from Altinstadt, Alsace. Nieces of Sociètè member O.M. Redon, they both died of yellow fever within weeks of each other in October 1872. They were buried in vaults 20 and 22 of the Lafayette No. 2 society tomb. While the people buried in this tomb overwhelmingly shared a linguistic and cultural bond, there is no shortage of strangers among the burials in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Although the tomb was built for French society members, those members were not always French. Strangers in a Strange Land: Non-French Buried in the French Tomb A handful of foreign-born non-French people were laid to rest in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. Their stories contribute to the greater narrative of the society which at its heart was thoroughly New Orleanean in its cultural interactions. From Germany, Catherine Deffenback and brothers John and Jacob Schwenck were buried in this tomb at their time of death. The Schwenck brothers owned a saloon together on Magazine Street.[3] Leon Vignes, from Mont-de-Marrast, France, mourned the death of his Irish-born wife, Margaret, in 1884. She is buried in vault 35. Leon died fifteen years later and was buried in vault 38. He was not the only person to join the matrimonial melting pot: The wife of J.M. Gelé was born in England and died in 1872, buried in vault 26. Perhaps the most interesting foreign-born member of the society is not buried in the Lafayette No. 2 tomb but instead only blocks away in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, although no tablet remains to mark his name. Louis Savini was born in 1830 in Mortara, Italy. By the time he was eleven years old, he and his family had taken residence in New Orleans. From the very scant documentation remaining, Savini appears to have led a colorful life. He owned a saloon in what is now the Central Business District on Common Street, near the Mississippi River.[4] For reasons unclear from available records, Savini joined the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson in 1874. Only months after joining the group, however, Savini was struck down by a “cerebral fever,” which could indicate encephalitis, meningitis, or scarlet fever. He died on June 1, 1874 in his home on Poydras Street. The Sociètè not only furnished his burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, but also provided a procession befitting a French society member. Savini was buried in the tomb of his brother, Paul Savini, in Quadrant 2 of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Today, the tomb is in a state of dangerous neglect and has lost the closure tablet bearing Louis Savini’s name. As the Sociètè aged, its members increasingly were New Orleans natives. Over time, both the children of members and other Francophone Louisianans joined, advancing the process of assimilation in a new country. The Family Tomb At least one hundred and forty-two individuals are buried in the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Some were recent immigrants with little or no family left behind. For a striking number of society members, however, the tomb was the final resting place for multiple generations. It has already been noted that Leon and Margaret Vignes rest near each other in this tomb. They are also interred with their son, Joseph, who drowned at the age of 14 in 1891. He is interred in the same vault as his mother. The Fortassin family likely also utilized the society tomb for the interment of multiple generations. In 1870, twenty year-old Gabriel Fortassin, Jr., arrived in New Orleans from Trie, France. His parents joined him as well. In 1882, he married Alexandrine Claverotte.[5] The two would briefly move to San Antonio, Texas before returning to New Orleans. In his lifetime, Gabriel would bury his parents in the society tomb, as well as five of his infant children. When he died in 1927, he was given a French Society burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2.[6] One of Gabriel’s adult sons, Baptiste Fortassin was also buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, in 1929. Two years later, Baptiste’s widow Marie Maille joined him. With no Fortassin tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, it is very likely they joined their relatives in this tomb, making it the last resting place of three generations of one family, with at least nine burials.[7] Other families utilized the society tomb similarly. Surnames such as Tujague[8], Abadie, Mouledous[9], Vignes, and Carrare appear multiple times through the burial books, representing multiple generations. These records also show combinations of the above-mentioned names, linked by intermarriage. Eleanor Vignes Tujague and Pauline Mouledous Tujague are both buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. Society members formed a strong, interdependent community. They even stood at each other’s deathbeds to witness a last will and testament.[10] Death and burial were only the final threads that tied these French-speaking New Orleaneans together. In life, they lived and worked beside one another. As the French Society of Jefferson, members lived predominately within the boundaries of the former Jefferson suburb (portions of present-day Garden District, Irish Channel, Central City, and Uptown neighborhoods). Burial records note the residences of a multitude of members as near the St. Mary’s Market and along Tchoupitoulas Street. Even more records note residence as simply “aux abbatoirs,” or “near the slaughterhouses.” Which is no surprise: the majorit of members were butchers. A Workingman’s Society The Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson shared members and celebrated social events with the Sociètè de Bienfaisance des Bouchers, or the French Butchers Society. Their enormous, eighty-vault society tomb remains also in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Members of each society lived near the Mississippi River, where cattle were unloaded at river docks. Until the late 1860s, the City of New Orleans had little regulation regarding the slaughter of livestock. Butchers were free to practice their trade where they pleased, usually near a market where they could sell their wares. This changed with a municipal law that required butchers slaughter livestock exclusively in a city-owned slaughterhouse, the goal of which was to prevent public health hazards.[11] Opposition to this law among butchers of both French societies led to civil unrest and years of legal battles. The case finally reached the Supreme Court in a landmark ruling known as the Slaughterhouse Case. Among the French and Butchers societies, the butcher’s trade was passed through generations and within a tight-knit community. Members lived in close proximity to each other, with addresses at Louisiana, Camp, Chippewa, Annunciation, Constance, Josephine, St. Mary, Tchoupitoulas, St. Andrew, Washington, Magazine, and Rousseau Streets. The propensity to take on the butcher’s trade among these society members is truly overwhelming. One casual cross reference of members’ names with an 1878 directory revealed nine butcher/members alive and working at the time: Gabriel Fortassin, Jr., Jean Abadie, Joseph Barrere, Pierre Lacaze, Bernard Lacoste, John William Lannes (Lannis), Pierre Sabatte, and Leon Vignes. The other three members searched, Victor Brisbois, Ulysses Mailhes, and Jacob Schwenck, were all listed as saloon owners or bartenders. Causes of Death If cursory research is to be trusted, the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson was populated by close friends who slaughtered animals and served alcohol for a living. When this living ended for each individual, however, the causes varied. It should be noted that 65 of the 142 burials (45%) in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb were for children under six years of age. The Fortassin family, who buried five children in this tomb, were by no means unusual in their parental grief. Joseph Bararre and his wife Amanda Mailhes buried four children as well, all of whom were interred in vault 8. The high concentration of child burials in this tomb has a dual explanation. In addition to the well-understood status of childhood illness and mortality in the late nineteenth century, it was also much more likely for a family to bury a child in a society tomb than one built for a family. Married couples without their own family tomb were unlikely to purchase a lot for the burial of a child or stillborn infant. Instead, it was much more affordable to inter the child in a wall vault or society tomb, if available. Furthermore, the spiritual and emotional benefits of society-supported burial of a child were likely comforting. A significant percentage of the 65 infant/child burials were the stillborn or nonviable infants of society members. The other children of the Sociètè died of many common childhood maladies, including lockjaw (tetanus), cholera, croup, seizures, and whooping cough. Six children were listed as having died either of “bad teething” or a jaw ailment. In the nineteenth century, a range of many ailments was attributed to the process of teething in toddlers, including intestinal disease, seizures, meningitis, or even crib death. About half of the burial records in the Sociètè burial book list a cause of death. Among the adult members, most causes of death of typical of the time period: apoplexy, Bright’s disease, consumption (tuberculosis), and yellow fever. Surprisingly, only four burial certificates mark yellow fever as cause of death. This statistical anomaly may be explained by society members being buried hastily during times of epidemic, either in other tombs or too quickly to fill the burial form completely. “A Mort et Sans Espoir de Guerison” A few members, however, appear to have died in a slightly more unusual manner. Among them are:

All of the above-listed men were members of the Sociètè who were buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb alongside lost children, fellow butchers, and more than a few bartenders, as well as many wives, nieces, and grandchildren. A Community Buried Together Nearly all vestiges of Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson have faded from popular memory. The tomb itself does not have a single carved name on any of its forty marble vault tablets. Yet within the decaying stucco vaults of this tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 are the relics of a great communal history that remains vitally significant to New Orleans cultural heritage. It is the hope that this research might connect the descendants of those buried in this tomb with their ancestors. The full burial rolls of interments into this tomb from 1872 to 1900 (up to the society’s merger with Sociètè Française d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans) have been uploaded to FindaGrave, in hopes their descendants may find them. The burial books are also available as an Excel Spreadsheet , MS Access Database, or PDF Document. Click here for burials listed by vault number. [1] Unless otherwise noted, all content is referenced directly from the original burial books as transcribed and documented by Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Links to these materials can be found at the end of this blog post.

[2] Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon, editors. Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1992), 112. [3] Edwards’ Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans, for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company 1872), 366. [4] New Orleans City Directory 1870, 531. [5] State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History. Vital Records Indices. Baton Rouge, LA, USA. [6] Times-Picayune, August 28, 1927, 2. [7] Times-Picayune, January 18, 1929, 2; [8] To our knowledge, if this family is related to Guillaume Tujague, restauranteur, it is only distantly. [9] Alternately spelled Moledous, Mouledoux, etc. [10] Pierre Lacaze, also from Trie, witnessed Sylvain Tujague’s final will in 1882. Louisiana Will Book, Vol. 21 (1880-1883). [11] “City Litigation,” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, May 30, 1869, 5. In this article regarding the Butchers’ filed injunction against the City, the author notes their injunction as “a string of reasons as clear and cutting as the keenest cleaver could demonstrate.” Recently, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC transcribed the burial records of the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, thanks in part to a grant from genealogist Megan Smolenyak. The Society was absorbed by the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans in 1900. Through this research and through extended investigation into the history of the society, its members, predecessors, and descendants, a rich portrait of the life of French-speakers in nineteenth- and twentieth-century New Orleans emerged. Today, we share the history of that society and its many milestones, members, and tombs. ARTICLE I: The association aims to improve physical, moral, and political fitness of its members; to lend each other assistance and relief in misery; to promote each other’s wellbeing, by council and by example; to collectively inspire the rights and freedoms of the home in all countries, and the practice of the duties, which alone can make them worthy; these are the primary obligations as members define them. – from the original constitution of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans, 1843 (translated from French).[1] The First French Benevolent Society in New Orleans On March 14, 1843, after four years of preliminary incorporation, the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (French Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society of New Orleans) was formally established with twenty-seven members. In its own words, the society formed as a result of increasing Americanization of the French colonial city after the Louisiana Purchase and into the Antebellum Era. The Sociètè Française was the first of many organizations in New Orleans with the aim of preserving French language and identity among its members. The Sociètè in New Orleans crafted their organization in the image of fraternal and masonic organizations in France, exemplified by the Grand Orient de France.[2] Similar values were emphasized: brotherhood, charity, social solidarity, and citizenship. The French model of freemasonry also emphasized laicity, or secularism. Among the founding members of the Sociètè in 1843 was a man who himself embodied the political nature of French freemasonry. Pierre Soulé (1801 – 1870) a French native and revolutionary who settled in New Orleans in the 1830s, shaped the early goals and tone of the Sociètè. However, he was elected to the United States Senate in 1847 and thus truncated his involvement. In this year, the Sociètè merged with the French Consulate. Minute books and histories of the Sociètè suggest that after Soulé’s departure, the political aims of the organization were abbreviated in favor of a charitable and social mission.[3] The Sociètè would come to be known for many things – its Bastille Day celebrations, its protection of the French language, its role as the French consulate for some time – but it was likely best known for its Hospital, which was an institution for over a century. French Hospital In the same year as the Sociètè’s founding, a French visitor to New Orleans donated thirty thousand bricks for the construction of a place in which the members could gather. The material was used to build the first French Hospital on Bayou Road near North Robertson Street, described by historians as “a center-hall, gable-sided, double galleried residence.[4]” The hospital, or Asile de la Société Française, cared for Sociètè members and their families. From 1847 to the early 1860s, the organization weathered multiple yellow fever epidemics in which as much as half of the membership was hospitalized.[5] In the early 1860s, the Hospital moved to St. Ann Street, a property donated by then-President Olivier Blineau. Blineau died shortly thereafter and was given the posthumous title of “Father of the French Society.” Originally meant only for society members, French Hospital was opened to all sailors of the French fleet in November 1862, in the event that an illness may require a stay on land.[6] With few exceptions, the Hospital was expressly for the use of members, their families, and those sponsored by members until 1913. In 1913, French Hospital expanded under the decision that “it was finally decided to build a clinic to treat strangers.[7]” Over the next thirty years, the Hospital would include a maternity ward, modern X-ray machines, and operation rooms. The original 1913 building became a well-known edifice on Orleans Street near Claiborne Avenue.[8] Tombs and Burial Benefits Throughout New Orleans history, it was common for societies to form around commonalities of nationality, profession, or background. Most societies would provide benefits similar to those provided by fraternal orders or by modern-day insurance companies. Among these benefits was frequently the option of burial in a society tomb, as well as funereal benefits for survivors. The Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans spared little time in establishing a society tomb for itself. On March 14, 1850, the Sociètè acquired a large lot in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 on Basin Street with the financial aid of the French Consul, M’r Roger. By August of the next year, the first stone of the tomb was laid at a formal ceremony. Beneath this stone, Sociètè officers laid a lead box, in which a copy of the organization’s Constitution, and parchment containing “the names of the President, members of the Consulate, and all members of the society” were placed.[9] The Classically-inspired tomb with an intricate sarcophagus at its apex was completed in the following years. In the early 1850s, the size of the tomb would have overwhelmed the landscape of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. The similarly-imposing Italian Benevolent Society tomb would not be built until 1857. The cross-gable roof of the tomb supported four cast-iron lamps (now missing), in addition to its large sarcophagus, giving it the appearance of a temple. Each corner of the tomb featured an upright torch fashioned of cast plaster. In historic photographs of the tomb, these torches were painted black.[10] In 1853 and 1856, President Blineau donated two additional lots in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 to the Sociètè. Either one of these donations may have been for the purpose of building an addition to the tomb. As is visible in the 1895 Library of Congress photograph, a smaller structure was built to adjoin the original tomb, comprised of fifteen vaults. This expanded the Sociètè’s burial capacity to seventy vaults, all of which could be reused over time.[11] Possibly as a result of a yellow fever epidemic in that year, rumors flew in 1867 that St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 would be permanently closed. In response, the directors of the Sociètè organized a picnic fundraiser to construct a new tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. The nearly $1,000 raised was utilized for the purchase of a lot, which was donated to the Sociètè. Mentions in Sociètè records as well as newspaper resources suggest that a society tomb was in fact built in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 for the use of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans. However, no tomb today bears the society name. The Sociètè maintained and repaired their tombs regularly, as was (and is) necessary with New Orleans tomb structures. In 1897 alone, the organization set aside nearly $500 por le fonds du Tombeau.[12] Regular limewashing, painting of plaster elements, cleaning of lamps and urns, and filling inscriptions with copper-based paint were annual expenses that contributed to the well-kept, beautiful structure seen in the 1895 Library of Congress photograph above. Funeral expenses were also part of member benefits. In an 1897 annual report, the Sociètè outlined these benefits specifically, including:

A Sister Society in Jefferson As the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans flourished through the 1850s and 1860s, an additional population of French-speaking people in what was then the City of Jefferson organized their own benevolent society. In the 1850s, the City of New Orleans was much smaller, and bounded on its upriver side by the Faubourg St. Mary and, farther upriver, the City of Lafayette. Over the course of the nineteenth century, New Orleans successively incorporated these municipalities into itself, creating the modern landscape of the city. Between modern-day Toledano and Joseph Streets, and bounded on the downriver side by the former City of Lafayette, the City of Jefferson was incorporated in 1850. Comprised of the Faubourgs Plaisance, Delassize, Bouligny, and others, the city would only remain independent for twenty years before being incorporated into the larger City of New Orleans.[13] It was here that the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson formed in 1868. The French speakers who lived Jefferson Parish and formed the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson were in many ways similar to their counterparts in New Orleans proper. In fact, in many cases they were related. Members of the Tujague and Carerre families joined and served as officers in both societies. Members of each group were often natives of the same departments in France, primarily the Pyrenees and Gers. Many had family in St. Bernard Parish as well as Orleans and Jefferson.[14] The Jefferson Sociètè was comprised of men who lived with their families “near the slaughterhouses,” or who lived on Tchoupitoulas, or near the St. Mary’s Market. They collaborated with and shared members with the Sociètè de Bienfaisance des Bouchers (the Butcher’s Society) who in 1873 brought the famous Slaughterhouse Case to the Supreme Court. A number of Jefferson Sociètè members were buried in the Butcher’s tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. The Jefferson Sociètè built its large, Classically-inspired, forty-vault tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 around 1872. The tomb is of extraordinary height, particularly in the landscape of this cemetery. Its primary gable pediment was carved with the name of the society, which once read “Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Ville de Jefferson,” although the “de la Ville de Jefferson” portion of the inscription appears to have been chiseled away after 1900. Below the pediment are stucco dentils, and on each side are cast-iron florets which likely cover structural tie-rods. The tomb has a number of unique additional features. On each side of its primary façade are niches which were once painted a brilliant Prussian blue, a historic pigment made with iron oxide. In each of these niches were marble statues of kneeling women, one of which had her hands raised in prayer, the other’s hands were crossed on her chest. Both of these statues were stolen between the 1950s and 1980s. The tombs gable-roof side projections hold most of its burial vaults, each enclosed in marble tablets and divided by slate slabs. All tablets of this tomb are uninscribed, leaving the names of those buried within to mystery until the recent transcription of burial books – which revealed the names of at least 150 people buried in this tomb between 1872 and 1900. The Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson participated in the celebrations of a number of French societies in the city. In addition to the New Orleans Sociètè, the Jefferson Sociètè was frequently documented in relationship with the Fourteenth of July Society and the Children of France. 1900: Merging of the Societies By 1896, at its twenty-seventh anniversary, the Jefferson Sociètè had “fifty or sixty” members – a roster that the Daily Picayune regarded as “not quite so large a membership now as at other times in its history.”[15] Officers from the Butcher’s Society and the New Orleans Sociètè, the French Orpheon, and the Fourteenth of July Society raised glasses of wine to the Jefferson officers B. Tujague, O.M. Redon, F. Desschautreaux, T. Abadie, and M. Despaux – most of whom would eventually be buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. It was only four years later that the dwindling numbers of the Jefferson Sociètè merged with their older counterparts at the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans. The merger was completed on January 3, 1901, which records report “brought 41 new members to the society. It also brought to the Society a tomb of forty vaults, nearly new, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2.”[16] The New Orleans Sociètè had merged with other organizations before, beginning with the French Consulate in 1847. In 1895, they also absorbed the Philanthropic Culinary Society of New Orleans, who brought with them an additional burial place: a five-vault tomb located in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street.[17] A Centennial Celebration and Gradual Decline While the New Orleans Sociètè had gained the members of its Jefferson counterpart, its own members were dwindling. This was the case for many benevolent societies in New Orleans after the 1930s. As the need for private hospitals waned, so did French Hospital. In the case of other societies who supported other causes such as orphanages or schools, the need for their ministries decreased with the rise of social services. As insurance corporations developed, private societies no longer fulfilled a necessity. For the French society, decreased interest in the French language likely took a toll, as the New Orleans Sociètè operated exclusively in that language. In 1943, the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (and, by merger, de la Ville de Jefferson) celebrated its 100th Anniversary.[18] A celebration was held at the French Hospital at 1821 Orleans Avenue, with a dance to follow at the American Legion. The festivities appeared to hold true to the organization’s civic dedication. French leader Andre Lefargue addressed the crowd with patriotic notions of the French and Americans once again fighting in a war together. Appeals were made to the crowd to donate to the Red Cross for the war effort. Nine French cadets training at the New Orleans Naval Air Station were special guests of honor.[19] Said society president Henry Bernissan at the centennial celebration, “the first 100 years of the society is merely the initial performance. We expect to improve our methods with every passing day.”[20] Yet the Centennial pamphlet published by the society seemed to suggest a different prescience: The current charter does not expire until the year 1972. Therefore, the Society has 29 years to run. It is hoped that the majority of the current members celebrating our centennial will prosper alongside the society until the end of its charter.[21] On October 31, 1949, only six years after its centennial, the closure of French Hospital on Orleans Avenue was announced.[22] The building was sold to the Knights of Peter Claver, an African-American Catholic Society, who utilized the building until the 1970s, when an adjacent structure was built. The French Hospital/Peter Claverie Building was demolished in 1986. The Knights of Peter Claver buiding remains on this site. The exact year in which the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans formally disbanded is unclear. Unlike their various balls, benefits, picnics and celebrations, this milestone in the organization’s history was not published in newspapers. However, it does not appear as if the Sociètè survived to the end of its charter in 1972. In a 1972 newspaper article, a passing reference was made to the Sociètè, “which for many years maintained the old French hospital on Orleans Street. The French Society folded a number of years ago.”[23] A Legacy of Burial Places Physical evidence of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle is scant in the landscape of modern New Orleans – except for in the cemetery. Each day, hundreds of visitors pass the Sociètè Française tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Without its cast-iron lamps and jet-black torches, it fades into the cemetery scene a little more than it once did, but it remains. For the more than 150 people buried in the Sociètè Française de Jefferson tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, that memory is much more tenuous. A number of trees that began growing in the tomb roof in the 1940s were cut down only this year, leaving a structure in significant need of repair. The brilliant colors of the blue tomb niches, the contrast of its white walls against black slate, its green copper drain pipes, have all faded to flat greys and exposed brick. Without names on the tomb tablets, it has been difficult for families to realize their ancestors are buried within. Yet with this project it is our hope that new resources will supply stakeholders with important information with which to regrow a connection to this remarkable structure, which represents more than a century of French fellowship in New Orleans. In our next blog post, we will share the lives of the people buried in this tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. The full burial rolls of interments into this tomb from 1872 to 1900 (up to the society’s merger with Sociètè Française d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans) have been uploaded to FindaGrave, in hopes their descendants may find them. The burial books are also available as an Excel Spreadsheet , MS Access Database, or PDF Document. Click here for burials listed by vault number. [1] Abrege Historique de la Societe Francaise d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, c. 1903, Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection. This and nearly all documentation of the Jefferson and New Orleans societies are entirely written in French. All translations by Emily Ford, who is by her own admission not fluent in French. Difficult phrases are presented in their original French in [brackets].

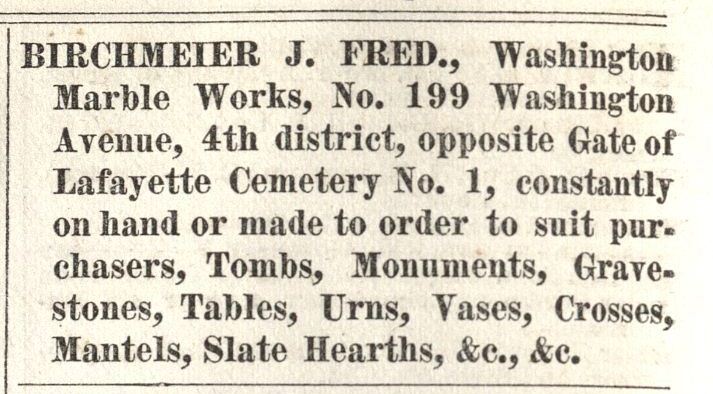

[2] Founded in the 18th Century, the Grand Orient de France permitted female membership by 1773. Documents of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans and of Jefferson suggest that neither society permitted female membership at any time. [3] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, published 1943 by the Sociètè, 9. Louisiana State University Special Collections, MSS 318, 1012. [4] Roulhac Toledano, Mary Louise Christovich, and Robin Derbes, New Orleans Architecture: Faubourg Tremé and the Bayou Road (Gretna: Friends of the Cabildo, 2003), 82. [5] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 19-21. [6] Ibid., 21. [7] Ibid., 39. [8] “New French Hospital Dedicated Yesterday,” Times-Picayune, February 24, 1913, 13. [9] Ibid., 15. [10] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 9. [11] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 19. [12] “Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, Rapport annuel, 1897,” Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection. [13] Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2008), 290. [14] From the records of Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson burial books, Louisiana State University Special Collections. [15] “The Old Jefferson Society Celebrates its 27th Birthday,” Daily Picayune, November 16, 1896, 10. [16] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 37. [17] Ibid., 35. [18] “French Unit Will Fete Centennial,” Times-Picayune, March 14, 1943, 11. [19] “Society Marks Centennial Day,” Times Picayune, March 15, 1943, 25. [20] Ibid. [21] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 51. [22] “25 years ago,” Times-Picayune, October 17, 1974, 19. [23] Times Picayune, September 24, 1972, 6. Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. Full text here: http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/ The history of sextonship in New Orleans is as old as the city’s cemeteries. The origin of the cemetery sexton derived from European tradition, in which the sexton would care not only for the graveyard surrounding a church sanctuary, but also for the church itself. In New Orleans, the first sextons likely were part of a lay ministry, employed by the Catholic Church to care for St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and, later Saint Louis No. 2. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, however, was not administered by the Church or any other religious group. Instead, it was established in 1833 by the municipality of Lafayette, a suburb of New Orleans. Translating from the ecclesiastical to the secular sphere, the City of Lafayette employed a sexton to care for the cemetery at Washington Avenue and Prytania Street. From the cemetery’s founding into the 1950s, at least twenty-two individuals served as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Many were stonecutters and tomb builders, some were additionally undertakers, politicians, and masons. They cared for the cemetery in times of epidemic, vandalism, and population shifts. Through their stewardship, the landscape of the cemetery was formed. Phil Harty and the First Sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Up to and after the City of Lafayette was incorporated into the City of New Orleans in 1852, the role of the sexton was to perform and record interments, submit interment records to the city council, and maintain the cemetery grounds. It was also his responsibility to enforce the ordinances of the city and state regarding interments and sanitary conditions.[1] These laws included the collection of a certificate of burial (presented by a physician or coroner to the deceased’s family), ensuring the deceased was properly placed in a coffin, and construction regulations regarding tombs. Failure to perform these duties resulted in punishment from City Council.[2] Sextons were additionally paid a fee for each interment based on the deceased’s status as colored or white, child or adult, and whether the interment was to be an act of charity. In the nineteenth century, these fees varied from 50 cents to $1.50, with a $3.00 charge for the opening and closing of tombs and vaults, to be paid by the owner.[3] The first sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was most likely B.S. Quinman, who served from 1832 to 1844.[4] After Quinman, H.G. Hicks served briefly in the position. While many sextons constructed tombs in Lafayette No. 1, no structure or tablet in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 bears either man’s signature. Their successor, however, seems to have made more of an impact on the cemetery. Philip Harty, mostly referred to in documentation as Phil Harty, served as Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 sexton from 1855 to 1861. [5] Only one of his signed works survive amidst the rows and aisles of tombs: the tomb of A. Thomas, located near the rear gate.[6] He lived at 197 Washington Street, across from the main gate of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. This address was utilized by numerous sextons and stonecutters throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Today, the lot is listed as 1427 Washington Avenue. The building is currently utilized as the administrative offices for Commander’s Palace restaurant. Phil Harty died August 14, 1861. His obituary, describing his death as “sudden,” states that Harty was well-known as a sexton and a “hearty, merry fellow up to the very hour of his death. Thousands he has introduced to the narrow house, and now he has gone himself, with scarcely a moment’s warning.”[7] D.F. Simpson, a local stonecutter, followed Harty as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1863 to 1868. He was also a stonecutter and tomb builder – his office was located on Race Street.[8] Examples of his work remain in the cemetery today, including the Stearns tomb and at least three constructed while Simpson was in business with later sexton J. Frederick Birchmeier. Following D.F. Simpson were James Hagan (1830-1908, sexton 1865-1867), and Joseph F. Callico (sexton 1867-1875).[9] James Hagan served as state senator representing Orleans Parish from 1880 to 1884. Based on remaining signed tombs and closure tablets, J.F. Callico was one of the most prolific stonecutters among the sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1: today, nearly thirty tablets in the cemetery bear his signature. 1865 – 1900: A Thriving Craft Community The late 1870s were unusual for the stewards of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in that no one individual served for more than a few years. As had occurred in previous years, especially 1853, yellow fever epidemics were particularly difficult times for sextons. It is possible, then, that the 1878 epidemic, the marks of which are still very visible on the tombs and tablets of Lafayette No. 1, caused an upset in the administration of the cemetery. In quick succession, Dennis Irvin, Cornelius Donovan, John Barret and Patrick Gallagher served as sextons from 1876 to 1880. Patrick Gallagher likely left his office due to accusations against him that he attempted blackmail on an unnamed person.[10] After these men, J. Frederick Birchmeier, a stonecutter who had been active in Lafayette No. 1 for decades, became sexton.[11]

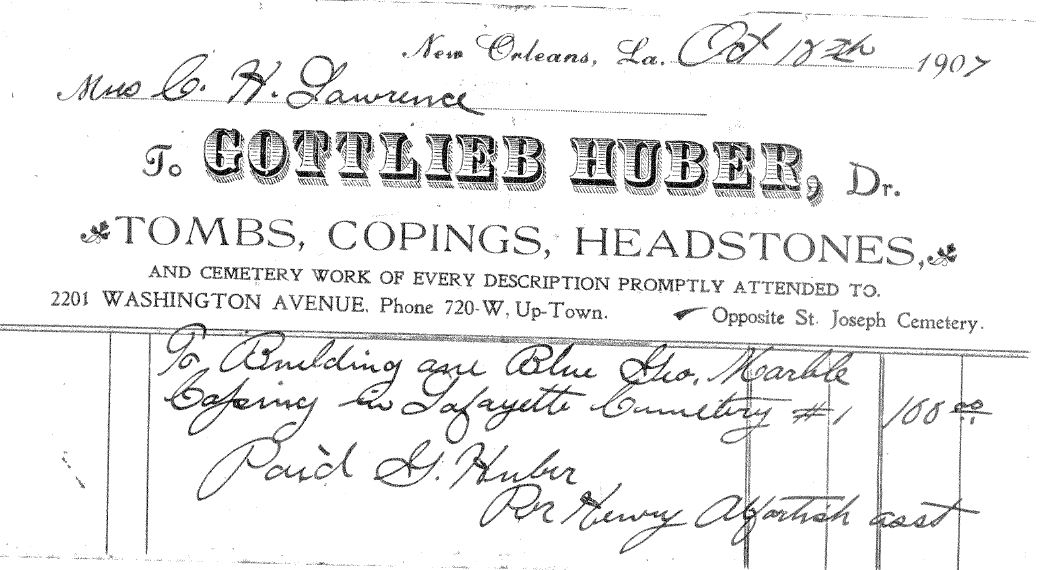

The turn of the twentieth century brought to Lafayette No. 1 a close-knit community of stonecutters and tomb builders, many of whom served as sextons. After J. Frederick Birchmeier retired, his colleague Hugh J. McDonald (1853-1895, sexton 1886-1895) took over stewardship of the cemetery. After McDonald’s death, stonecutter Charles Badger succeeded him. Badger was also the husband of Birchmeier’s daughter, Margaret.[14] Both Badger and McDonald were close colleagues of Gottlieb Huber, who was sexton from 1902 to 1915. The legacy of this community would continue for the next thirty years through another young protégée of these men. 1900 – 1945: The Alfortishes In 1911, Henry Alfortish became assistant to Gottlieb Huber at Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Alfortish also worked with Huber privately, and would absorb Huber’s business after his death in 1926.[15] The influence of Alfortish and, later, his son Edward, would greatly change the cemetery. In the 1920s, Alfortish declared numerous lots abandoned and “open for sale.” He sold these lots and tombs to new clients and, additionally, provided replacement deeds for families who had lost their tomb ownership documents. It was also under the sextonship of Henry Alfortish that the wall vaults once located along Sixth Street were cleared and demolished. Numerous coping tombs located along this wall today bear Alfortish’s signature.[16] Edward Alfortish assumed sextonship of Lafayette No. 1 in 1942. However, the role of sexton was no longer seen as relevant in the city-owned cemetery. Few burials were made compared to the heyday of Lafayette No. 1, and many of the responsibilities of sexton could be carried out by other city officials. By around 1950, no individual would serve as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 again. The caretakers of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1833 to 1950, built the cemetery as it is seen today. They designed and constructed its tombs, removed and replaced landscape features, fostered its dead and their families, and protected the cemetery from harm. Their names are placed alongside the names of Lafayette No. 1’s most famous residents, in the form of carved signatures at the bases of closure tablets and headstones. The story of this National Historic Landmark cemetery is very much their story. [1] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4; State of Louisiana, The Revised Statutes of Louisiana (J. Claiborne, 1853), 386.

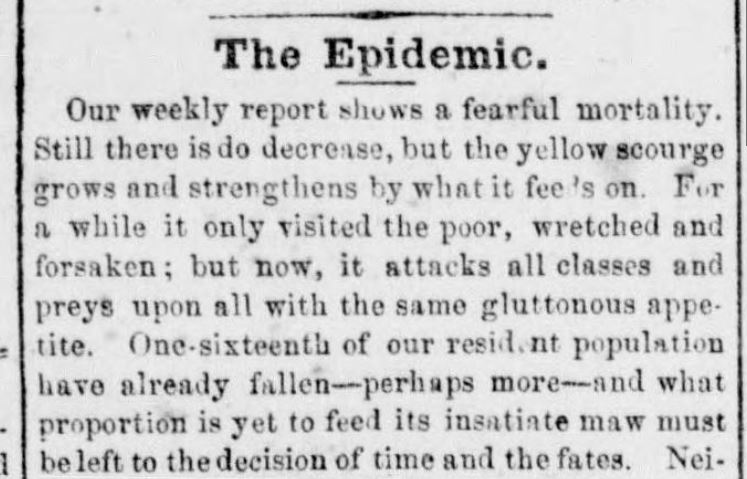

[2] “City Intelligence: Board of Health,” Daily Picayune, August 4, 1853, 1. [3] Ibid.; Currency evaluation oriented around historic standards of living, these costs equate to approximately $20-$40 per interment and $81 (2011 dollars) for the opening/closing of a tomb or vault. (www.measuringworth.com) [4] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84 (Baton Rouge: Leon Jastremski, 1884), 40. [5] Daily Picayune, February 15, 1855, 6; Mygatt & Co.’s Directory for New Orleans, 1857, W.H. Rainey Compiler. L. Pessou & B. Simon Lithographers, 23 Royal Street, New Orleans, 1857, 49; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for the Year 1859 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1858), 377; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1860 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1859), xvi. [6] Based on a 2012 survey of all signed craftwork in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. The Isaac Bogart tomb, located in Quadrant Three of Lafayette No. 1, is documented in the 1981 Save Our Cemeteries/Historic New Orleans Collection Survey of Historic Cemeteries as having a tablet signed by Phil Harty. The tablet has since been lost. [7] “Sudden Death,” Daily True Delta, August 15, 1861, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 18, 1866, 3. [9] Based on directories and municipal documents. [10] “An Official Suspended,” Daily Picayune, October 9, 1878, page 2. [11] Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1880 (New Orleans: L. Soard’s Publishing Co., 1880), 456; Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1882 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1882), 142; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1883 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1883), 452. [12] “A Singular Case,” Daily Picayune, June 14, 1868. [13] Receipt from J. Frederick Birchmeier to the widow of John Paul, Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 365. [14] Daily Picayune, February 8, 1891, 1. [15] Times-Picayune, January 20, 1926, 2. [16] Receipts for lots Quadrant Three, Lots 16 and 17, Quadrant 1, Lots 270-275, the Moulin, Gonea, Legien, and Bittenbring tombs. Sexton’s book, page 127. Historic New Orleans Collection, Leonard Victor Huber Collection, MSS 365. The third in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. 23,707 infected. Not less than 4,600 dead. Such was the toll of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in New Orleans. The Crescent City was ground zero – the first point of contact in the United States for an epidemic that swelled north and eastward from July through November, taking 20,000 souls in total. Dozens of burials in each cemetery each day led one report to state that, in a sense, each day of the summer of 1878 had been All Saints’ Day. On the day of the holiday itself, many graves still retained the decorations of burial.[1] And the epidemic was not even completely over.

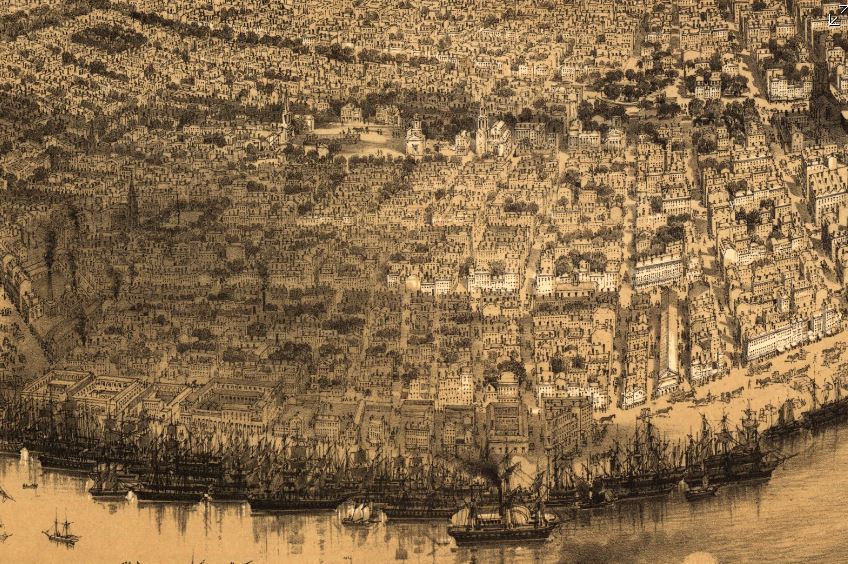

In the days leading up to All Saints’ Day, some health officials even cautioned against the yearly tradition of decorating and caring for loved ones’ graves. Said the Daily Picayune: It should be mentioned… that some physicians are of the opinion that, owing to the extraordinary number of interments during the summer and the prevalence of infectious disease, it would not be safe for a general decking of graves to be carried out as on occasions of the past.[2] First in a five-part series of All Saints' Day through New Orleans history New Orleans heritage is steeped in holidays and celebrations. Amidst the hedonism and mystic antics of Mardi Gras, Twelfth Night, and other festivals is the contrasting solemnity of All Saints’ Day. Part of the Catholic calendar since the fifth century, All Saints’ Day (also known as the Feast of All Saints, Hallowmas, and All Hallows) has its origins in Roman, Germanic, and Celtic celebrations seated in prehistory. Today it is celebrated on November 1, although some Eastern Orthodox and Protestant denominations celebrate it on the first Sunday of November. The feast day began as a holy day in which the lives of the Catholic Saints were remembered and honored. However by the time of the arrival of French and Spanish colonists to New Orleans, the day rather signified the recognition of all saints, “known and unknown,” and more generally the remembrance and communal mourning of the dead by their survivors. By 1853, the oldest above-ground cemetery in New Orleans (St. Louis Cemetery No. 1) was 65 years old, and the imported traditions of above-ground burial and observance of All Saints’s Day enjoyed great significance in the rituals of the Catholic and Protestant communities. From the Catholic St. Louis Cemeteries to Protestant Girod Street, municipal Lafayette, and fraternal Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows’ Rest, the day was observed and reported on – not only as a day of mourning, but one of cultural spectacle, high style, and great charitable expectations.

From the numerous complaints made this morning of the careless manner in which the coffins containing dead bodies are left at the Fourth District cemeteries, it would appear that there are not enough hands employed there to bury the dead. The hearses bringing them place the coffins at the gate of the cemetery, and there, it is stated, numbers of them remain for hours, and in some cases all day and all night, the effluvia given forth reaching houses four and five squares off. … it is a sad enough necessity that we should live in the midst of an unsparing epidemic… But it should be the last reproach a city should receive, that she cannot bury her dead decently and respectably, in accordance with the feelings in which every human being participates.

The devastation of the epidemic lay not only in the cemeteries, but ever more so in the homes for widows and orphans. Benevolent associations, the members of which were bonded by nationality, profession, or religion, incorporated into All Saints’ Day a tradition of charity in which the orphans of various asylums would be present in the cemetery, collecting alms to support their care. Among these asylums was that of the Catholic orphan boys of the Third District, which cared for 300 children in October of 1853, and predicted another 100 within the next month. This institution, among others, stood present at the Catholic cemeteries on November 1, hoping for enough donations to build a new wing to accommodate their new charges.

The Daily Crescent describes a day of crowded cemetery avenues and people of all ages, “singularities of every hue, and representing every nationality… not before midnight were the decorations complete. It was then that thousand tapers and waxen lights everywhere covering the tombs were lit up, and a light flashed over the scene, imparting to it an almost magical brilliancy.” Said one author to the editors of the Baton Rouge Daily Comet of New Orleans’ All Saints’ Day observance: "Now, however, I am so much of a Catholic that I like all Saints day [sic] – I am in favor of the custom of making an annual pilgrimage to the graves of those we loved in life…” this author, signed only as “L,” describes the throngs of people, the “gaudy” decorations, the invocations of beautiful hymns. Yet the pall of epidemic’s devastation burns through even the most endearing recollections of All Saints’ Day 1853. “L.” concludes his letter not with the solemnity of honoring the dead, but with the discussion of the recent suicide of a New Orleans lawyer: He was buried on Sunday [October 30] followed to the grave by a large number of citizens. While the long cortege of carriages which followed his remains were passing slowly down the street to the Protestant Cemetery, another funeral came dashing along Hevia Street [now Lafayette Street], followed by a half dozen empty carriages, and all driven at a smart trot, as if in a hurry to get the dead out of sight as soon as possible. The latter procession had just time to cross the path of the former ere it came up making a forcible contrast in appearance and character between the two. One was a rich man going to lay down in his last resting place, the other was a poor stranger hurried to his final bed. When earth has reclaimed what was of her, who will be able to distinguish the ashes of the one from the other? Sources:

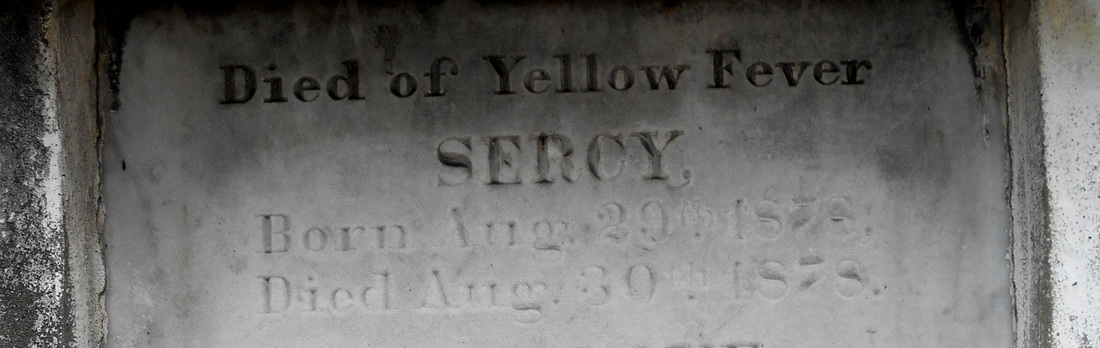

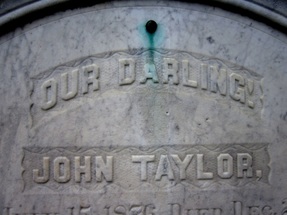

Walter Farquhar Hook, A Church Dictionary (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1852), 16. “Burying the Dead,” Daily Picayune, August 8, 1853, 1. “Female Orphan Asylum,” Daily Picayune, October 23, 1853, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 28, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 31, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, November 2, 1853, 1. “Correspondences,” Baton Rouge Weekly Comet, November 6, 1853, 1.  Detail of closure tablet for John Taylor, infant victim of 1878 Yellow Fever epidemic, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Photograph by Emily Ford. Detail of closure tablet for John Taylor, infant victim of 1878 Yellow Fever epidemic, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Photograph by Emily Ford. Yellow Jack, the Saffron Scourge, Bronze John: Yellow fever was a chronic fear, a “fearful ravage” in New Orleans from the time of its founding through the first years of the twentieth century. We often see remnants of the great sweeping epidemics of 1853, 1866, 1878, and other years carved in the stone of our cemeteries. While the silent presence of dozens of July, August, and September death dates that surround one in any corner of a New Orleans cemetery can be striking, the yellow plague carved even more drastic elements into the landscape. Entire sections of cemeteries re-developed by stonecutters and tomb builders to accommodate the incoming deceased are lost to our eye by modification and decay. The “Yellow Fever Mound,” a section of Girod Street Cemetery, was lost altogether with the demolition of that cemetery in 1957.[1] The role of sextons[2], stonecutters and tomb builders in this time was grim. In the summer “sickly season,” when all those who could afford to left the city for drier, cooler climbs, these craftsmen and caretakers were obligated to remain and make their trade available. This meant much more than building tombs as quickly as possible – since many stonecutters were sextons themselves, it meant managing the overwhelming presence of deceased bodies, many of which had no tomb or lot into which they could be interred. In some cases, victims were interred of by way of mass grave. In many more cemeteries beyond Girod, laborers were hired to dig long rows for the burial of simple donated caskets, covered up with small mounds of earth. In other cases, charities could accommodate the cost of burial in wall vaults. Often, families lent the use of their private tombs to friends with deceased spouses or children.

For further reading:

Benjamin H. Trask, Fearful Ravages: Yellow Fever in New Orleans, 1796-1905. Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2005. Jo Ann Carrigan, The Saffron Scourge: A History of Yellow Fever in Louisiana, 1796-1905. Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1994. [1] Huber, Leonard Victor, and Guy F. Bernard, To Glorious Immortality, The Rise and Fall of Girod Street Cemetery, New Orleans’ First Protestant Cemetery, Alblen Books, 1961, 9. [2] Officially-appointed cemetery caretakers. This role originated with church vicars and later extended to municipal, church, and fraternally-appointed positions. [3] New Orleans Public Library, http://nutrias.org/guides/genguide/burialrecords.htm [4] The “Bayou Cemetery” potter’s field was established in 1835; while many references suggest the site was redeveloped and became St. Louis Cemetery No. 3, some sources suggest the site of the cemetery to have been elsewhere. [5] Bennett Dowler, M.D., “Tableaux, Geographical, Commercial, Geological and Sanitary of New Orleans,” printed in Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1852 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1852): 19-20. [6] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” New Orleans Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4. [7] “History and Incidents of the Plague in New Orleans,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7, Issue 39 (August 1853), 800. [8] “The Fever,” Daily Picayune, July 30, 1853, 2. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly