|

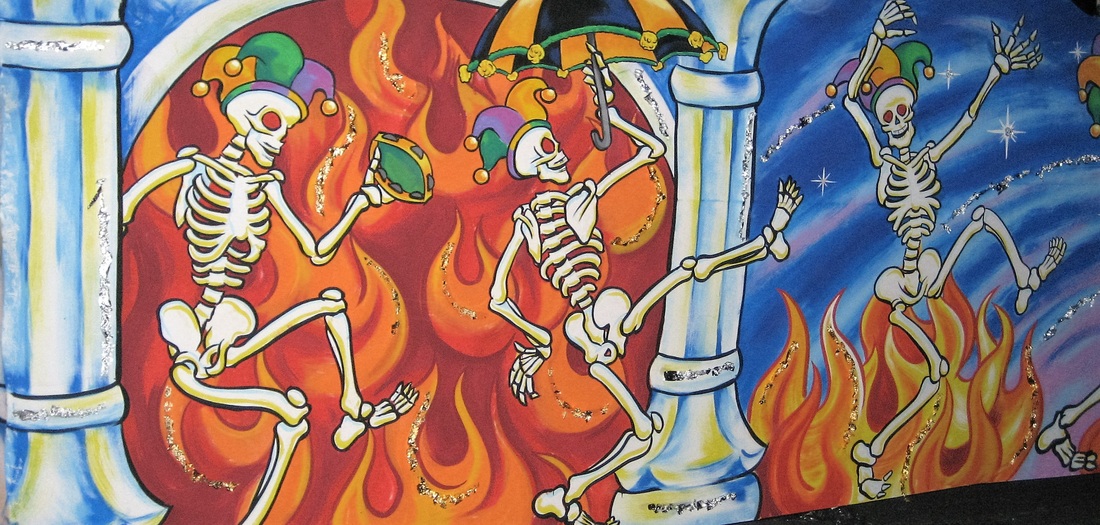

Carnival traditions like Mardi Gras and its Old World predecessors originate in Catholic pre-Lenten traditions and even pre-Catholic pagan traditions, each of which focused on the reversal of social and class roles, enjoyment of the senses, and indulgence in the face of repentance and self-denial (be that in the form of the Lenten tradition or the last months of winter without fresh meat and vegetables). In both ancient and modern contexts, Carnival is traditionally a time of celebration of life, focusing on earthly delights in the face of mortality. Yet despite these overarching themes, death and cemeteries still creep in. Beginning in Europe and later thriving in New Orleans, death has a habit of crashing Mardi Gras parties. The Triumph of Death in Florence In 1930, the Times-Picayune related an age-old story of one of the most famous appearances of Death at Carnival, in Florence, Italy, in the early 1500s: Then, suddenly, there came in sight a fiery procession, every member of which carried a torch. Under the torch flame it could be seen that every rider wore a death’s head and a black shroud. The death’s march came closer, and the horrified spectators saw that halfway down the line of parade was a covered cart drawn by four oxen, all four hung with black cloths painted with skulls and crossbones… On a pedestal in the center of the roof [of the float] stood the figure of Death, with the light the torches streaming through his hollow eye-sockets and empty ribs, and in his hand his scythe. At his feet lay six open coffins, within which could be seen six bodies wrapped in shrouds… When the procession reached the public square the skeleton attendants blew a trumped blast, and the shroud-wrapped bodies stood up in the coffins and chanted: “As ye see us, dead we be; Dead like us, ye we’ll see; We have been just as ye, Ye shall be just as we.”[1]

The famous Triumph of Death parade occurred in either 1511 or 1512 – one account states 1506 – and was engineered by the painter Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522). Di Cosimo was recently referred to as “the strangest master of the Florentine Renaissance,” by an author that counted the Triumph of Death parade as one of his accomplishments. Most of this history of di Cosimo’s life comes from 16th century artist and historian Giorio Vasari. Vasari’s account of the parade describes a car (float) decorated by di Cosimo to appear as “a mobile cemetery,” from which the costumed dead would spring from either tombs or caskets, and sing to the spectators of their inevitable mortality. The procession was “designed to terrify, but it also provided shock value and gruesome entertainment.[2]”

Although 1506-1512 represented a lull in the ever-occurring waves of Black Plague epidemics, the presence of death was never too far from the Florentine consciousness. Piero di Cosimo himself is assumed to have died of plague in 1522. That the Times-Picayune revived this four century-old tale for Mardi Gras 1930 is not entirely surprising. By this time, death was already marching in the parade. Beyond a strange 1911 incident in which a parade actually took place in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 (to be discussed in our next blog post), the ranks of Mardi Gras Indians had already, by this time, included a tribe of ghostly marchers. Deathly Maskers The North Side Skull and Bones Gang has its origins in the early 19th century and developed in the early 20th century alongside other African American Mardi Gras traditions like the Baby Dolls and Mardi Gras Indians. In a tradition that continues today, members of the North Side Skull and Bones Gang wake up before dawn on Mardi Gras day and parade from the Backstreet Cultural Museum through the Tremé neighborhood ringing bells, shaking rattles and shouting, dressed as skeletons. Much like the Renaissance parade of Florence, the North Side Skull and Bones Gang reminds us all that “death is always lurking, and sooner or later, it will come knocking at your door.”

The Skeleton Krewe marches on Mardi Gras day down St. Charles Avenue and into the French Quarter. This interview by photographer Julie Dermansky with Skeleton Krewe founder Christopher Kirsch describes the history of the Krewe of black-clad skeletons with enormous papier-maché skull masks. In its classical purpose as a time of celebration and role reversals, Mardi Gras is a time where anyone can be anything they want to be. New Orleans’ great tradition of costuming emerges in full force, and the expression of so many human experiences bursts forth – be it in the form of vivacious parades or celebrations of death. From Renaissance Italy to the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, the grim reaper has frequently had a place at the parade. And dressing as a New Orleans tomb for Mardi Gras? Apparently, that too has been done. Next time we visit New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras traditions, we look at times when the party entered the cemeteries themselves – the St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 Marching Club, and a mad cemetery caretaker. [1] “Mardi Gras Joke Once Placed Ban on Night Parades: Comus Carries on Despite Florentines’ Strange Sense of Humor,” Times-Picayune, February 2, 1930, p. 28.

[2] Landon, William J., Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi and Niccolo Machiavelli: Patron, Client, and the Pistola fatta per la peste (University of Toronto Press, 2013) 49-52.

2 Comments

During Mardi Gras season, New Orleans sees increased tourist traffic to one of its most popular attractions: its cemeteries, particularly Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. It nearly seems counterintuitive to visit a place of death and remembrance on a trip so populated with mirth and celebration. Yet the relationship of New Orleans cemeteries to its carnival celebrations is much richer than simply beads on wrought iron or the odd Muses shoe left on a tomb shelf. While the Carnival celebration is one of life and vivacity, the themes of mortality and cemeteries often creep into the mix. From death-themed floats, krewes, and costumes to actual celebrations in the cemeteries themselves, our cities of the dead have been part of the Mardi Gras stage since the 19th century.

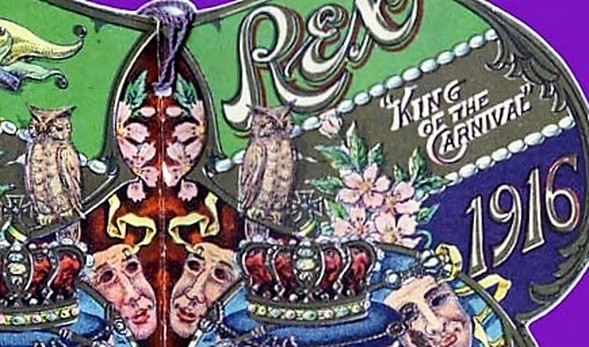

The first (and last) Jewish man to serve as Rex in New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, Salomon later moved to New York, although he visited New Orleans each year for Mardi Gras for decades after his reign. He died in 1925 and, surprisingly, it appears as if no one knows where he was buried. His final resting place seems to remain a mystery. His sister Delia, however, married local liquor dealer Otto Karstendiek and, upon her death in 1866, was buried in the only cast-iron tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Lewis Salomon was remembered as the first Rex for decades after his great parade. And although his final resting place may remain a mystery, it stands to reason that it does, in fact, exist someplace. Unfortunately, neither of these things were true for the third King of Carnival, Rex 1874, A.W. Merriam.

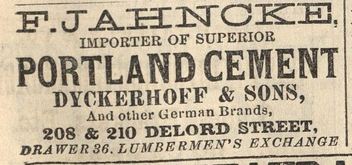

Merriam’s funeral was held days later and, in an even more tragic turn of fortune, his moral remains were paraded to Girod Street Cemetery, where he was interred.[1] While the old king may have rested in peace for as long as seventy years, Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957. Whether the remains of A.W. Merriam were transferred to Hope Mausoleum (as all unclaimed remains of white people reportedly were) or elsewhere, or at all, is anyone’s guess. No record concerning Girod Street Cemetery includes his name. Rex rules his chaotic kingdom for a day. He is emblematic of both disarray and refinement, satire and grace. Upon the close of the evening on Shrove Tuesday, when Rex has met with the Court of Comus and the curtain is drawn on the season, Rex relinquishes his rule until next year, when he returns in the guise of another man. For most of those who served as Rex, death and burial was a rather uneventful affair. Yet one King of Carnival would have a much greater impact on the cemeteries of New Orleans than simply being buried there. The Builder King In 1915, Mardi Gras took place on February 16. Rex this year was Ernest Lee Jahncke, who “headed the procession on a golden chariot of state symbolic of his imperial power… crowned with jewels and wearing a mantle of cloth of gold, [sitting] upon the throne in the center of the car, gracefully acknowledging the plaudits of his subjects.” The theme that year was “Fragments from Sound and Story,” and featured such floats as “The Fatal Kiss of Undine (the water nymph)” and “The Barter of Mephistopheles,” illustrating the bargain of Dr. Faust with the devil.[2] Rear Admiral (USNR) Ernest L. Jahncke (1878-1960) served as assistant secretary of the Navy from 1929 to 1933 and was himself a “renowned yachtsman.[3]” He was the son of Fritz Jahncke (1847-1911), a German immigrant and founder of Jahncke Navigation Company. The elder Jahncke was instrumental in one of the greatest shifts in tomb construction in New Orleans history. Beginning in 1879, Jahncke was one of the first building supply dealers to make Portland cement available for his clients. While Portland cement had been available elsewhere in the country as early as the 1860s, its use was nearly unheard of in New Orleans prior to Jahncke’s business. Since the 1700s, builders in New Orleans cemeteries used mortars, stuccoes, and renders mixed from hydrated lime, a material procured from burning limestone or oyster shells in a kiln. These materials required protection from the elements, usually achieved by limewashing tombs on a regular basis.

The materials which Fritz Jahncke had made available to New Orleans cemetery builders would eventually replace lime-based stuccoes and shift the way tombs were constructed. Just as importantly, Jahncke established himself as a great paver, paving sidewalks and streets using new cement mixes and replacing the brick and shell-lined avenues that once marked neighborhoods and cemeteries. These materials in cemeteries cut down on the need to mow grass or perform other landscaping. An unintentional consequence of this paving process was the exacerbation of drainage issues in cemeteries which continue to this day. The Jahncke family expanded from serving as Mardi Gras royalty a century ago to owning a shipyard and a dry dock in addition to the cement company. Ernest continued these businesses into the twentieth century and long after his reign as Rex. He was, however, the Rex spokesperson who, in 1942, announced that Mardi Gras would be cancelled that year in the spirit of solemnity and frugality in the face of World War II. Both Ernest and Fritz Jahncke are buried in Metairie Cemetery. In the next installment of our examination of New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras history, we bring death to the party itself and check out cemetery and mortality-themed floats, krewes, and costumes.

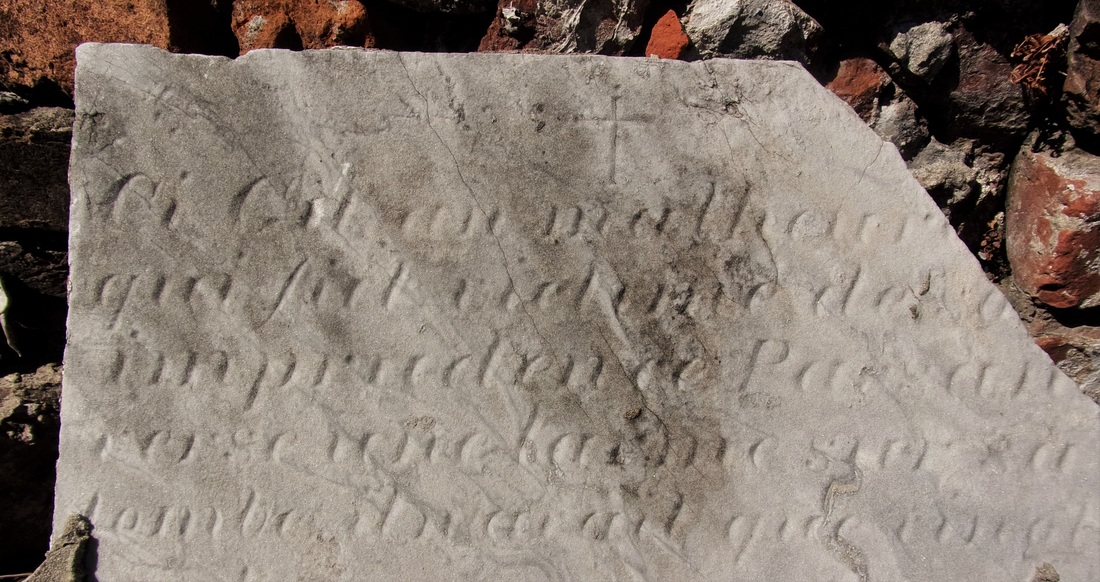

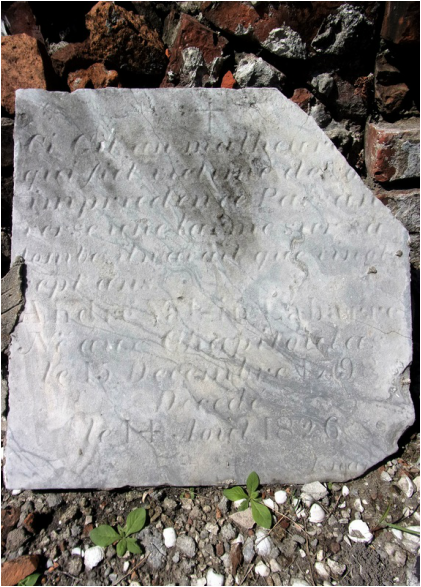

Special thanks to Mary Lacoste, author of Death Embraced, for drawing our attention and curiosity to Mr. Labarre. On any given day in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, hundreds of people walk down a back alley toward the “Musicians’ Tomb.” Led by tour guides, they may stop at a newly constructed-tomb or point out a newly-restored one. A few point out the tablet of André Valcin Labarre. One tour guide points to the loose-lying, grey-veined little tablet and states, “He was a bad boy,” as they walk past. The tablet is leaned up against a structure that has likely not been tended for nearly two hundred years. Half-collapsed, it is hardly a tomb any longer. Like uncountable burials in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, it is on its way to becoming completely erased. But Labarre’s tablet remains. Now broken and missing a piece, the Labarre tablet has long been referred to as among the most interesting in the cemetery. Its French inscription is difficult to read, let alone translate, but the words “victime de imprudence” remain visible. These three words have made the tablet a sensation, although nearly all accounts of its message have been incorrect. In a way, this is a story of a man who died young and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. But if this was all there was for André Valsin Labarre we wouldn’t be intrigued by him today. Instead, this is also a story of how one man’s epitaph led to a century of confused transcriptons, translations, and misunderstandings. In the nearly two centuries since his death, he continues to sow imprudence.

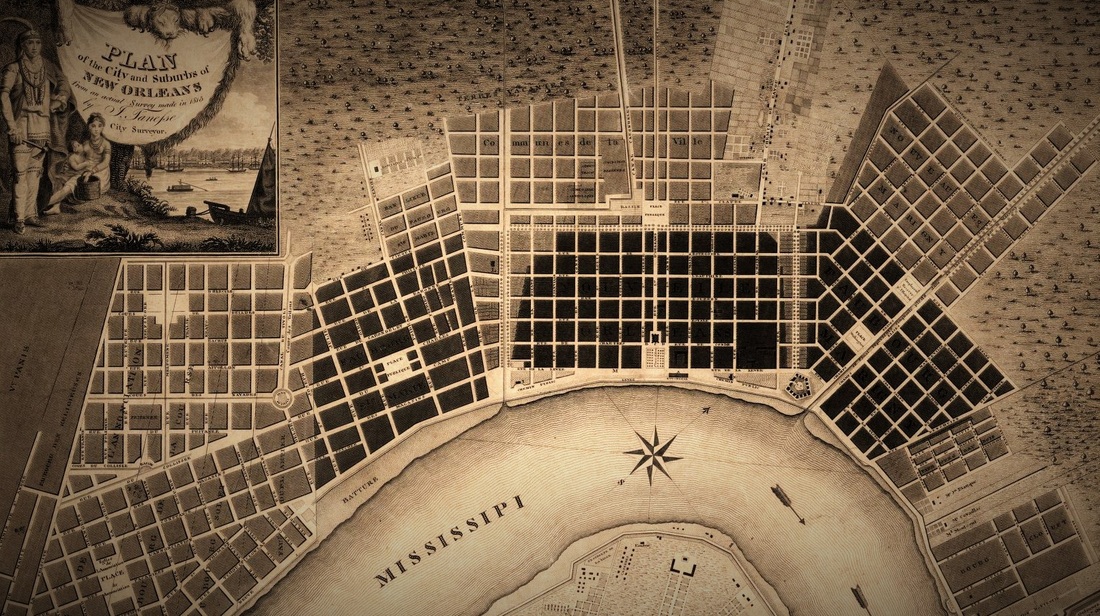

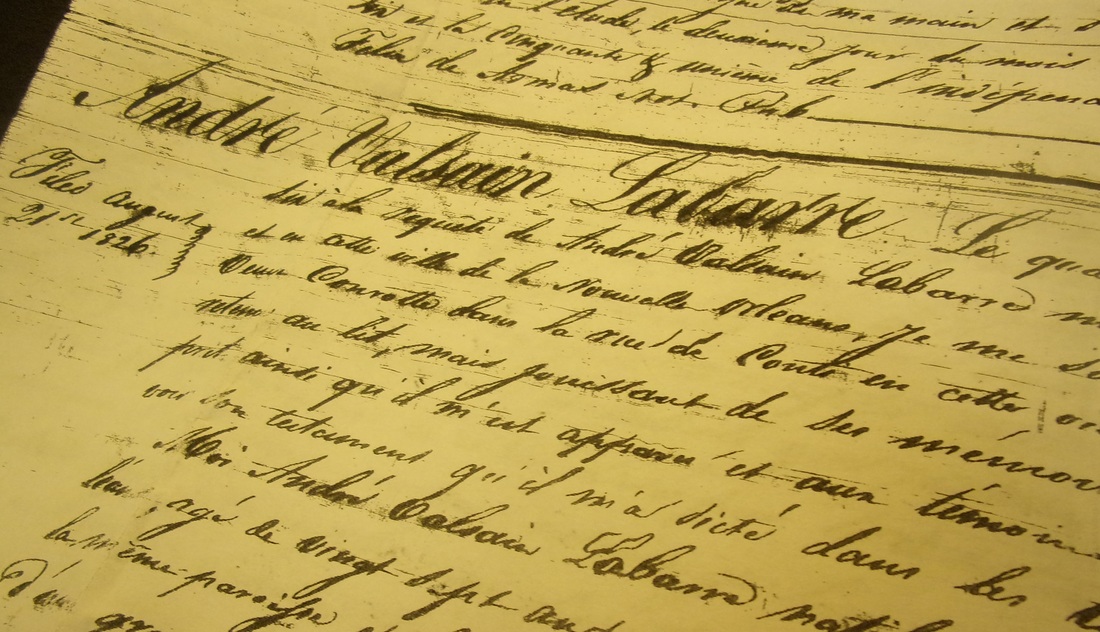

From the mid-1700s, the Labarre family owned significant holdings of land in what would become Jefferson Parish. Beginning with Francois Pascalis de Labarre Sr., who served law enforcement and municipal roles, a number of Labarre men claimed the post of sheriff in Jefferson’s early days.[2] Biographers and genealogists refer to the Labarre family as tied to their land, known as Chapitoulas Plantation or the Chapitoulas Coast.[3] The property line for this plantation is still demarked as Labarre Road in Jefferson. The family’s ancestral home, White Hall, is now home to the Magnolia School. André Valsin Labarre (usually addressed as simply Valsin) was born on December 15, 1798 at Chapitoulas Plantation. He is described as having less attachment to the plantation homestead than his parents, siblings, and cousins. According to one genealogist, Valsin was “the first of the Labarre family to move back to the city” of New Orleans since Franscois Pascalis Sr. purchased the Chapitoulas plantation in 1750.[4] Labarre lived in the Faubourg Marigny in 1822, when he married Virginie Conrotte (c. 1808-1850). The two had only one child, Samuel Placide Labarre, born December 4, 1822.[5] As for what André Valsin Labarre could have possibly done to deserve a tablet that suggests he died of his own imprudence, there is no clear answer. As we will see with later interpretations of his tablet, much is up for conjecture. His will shows a fondness for fine possessions: a “big horse of superior quality,” Spanish saddles and riding gear, a double-barreled hunting gun. He also owned five slaves: Fortune (30 years old), Thom (28), Constant (18), Maria (19), and Eliza (15). Thom and Fortune were “carters,” leading some to assume they “operated a cart and sold goods for their master.[6]” Beyond this means of income, it appears Valsin held no definite occupation, suggesting he may have been a man of leisure who enjoyed fine guns and horses.[7] On July 14, 1826, notary Carlile Pollock visited twenty seven year-old André Valsin Labarre at a home on Conti Street, likely the home of a relative.[8] Pollack was called to the house by Virginie Conrotte. Wrote Pollack: on j'ai trouvé le requerant malade retenir au lit, mais jouissant de memoire et entendement naturels, et bien d'esprit “there I found the sick man confined to his bed, but sound of memory and understanding, and in good spirits.” Pollock had been called to compose the last will and testament of André Valsin Labarre. In this will, Labarre named his oldest brother, Francois Pascalis Labarre II, executor and beneficiary of his property. He also requested that his brother care for his widow and son, Samuel Placide Labarre, and see that his son completed proper schooling.[9] No record documents exactly what had caused his illness. Valsin died on Monday, August 14, 1826, one month after writing his will. His obituary in La Courier de Louisiane only confounds the possible cause of his death, but describes him fondly: Mr. Valcin Labarre est décédé Lundi soir, à l'age de 27 ans, a la suite d'une longue et cruelle maladie. Doué d'une excellence constitution et a fleur de l'age, il semblant devoir fournir une longe carriere dans cette vies mais une entiere negligence de lui-meme a donné prise a la fatale maladie qui l'enleva a une nombreuse et respectable famille, a une interessant et jeune espouse, et un enfant en bas age. Mr. L. avait d'excellentes qualites qui le font regretter d'un nombreux cercle d'amis. “Mr. Valcin Labarre died Monday night at the age of 27, following a long and cruel illness. Endowed with an excellent constitution and in the flower of his age, it seemed he should have had a long career in his life, but a complete negligence of himself gave rise to a fatal sickness which swept him away from a large and respectable family, young and caring wife and a small child. Mr. L’s brilliant qualities will be missed by a large circle of friends.”[10] The Epitaph This sense of wasted potential is echoed in the poignant tablet his family erected at his grave. After close study of the tablet, as well as all past transcriptions of it, this is the epitaph carved for André Valsin Labarre:  Ci Gît un malhereux qui fut victime de son imprudence. Passant, verse une larme sur sa tombe, il n’avant que vingt sept ans. André Valsin Labarre Né aux Chapitoulas le 15 Decembre 1798 Decedé le 14 Aout 1826 Here lies an unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Passerby, shed a tear upon his grave, he was only twenty seven years old. André Valsin Labarre Born at Chapitoulas December 15, 1798 Died August 14, 1826 Labarre’s tablet was carved by Jean Jacques Isnard from gray marble. Isnard (1779-1859) was one of the earliest stonecutters in New Orleans. His prolific work can be found throughout St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Valsin’s death and burial in 1826 was the end of a short, but presumably happy life. His cause of death will likely remain a mystery. “Indiscretion or Excess” The phrase “victim of one’s own imprudence,” appears in rather specific narratives in the nineteenth century. It suggests a negligence of self-care by way of excessive living or failure to treat illness in its preliminary stages. For example, a woman who dies of consumption because she did not treat a cold was a victim of her own imprudence. Alternatively, the term “victim of imprudence” was frequently used in advertisements for men who had contracted venereal disease. In the case of Labarre, others have suggested perhaps the excesses of drink, although no record can confirm. For whatever reason, Valsin’s family requested such language for his tablet. Little would they know that the words they paid Isnard to carve would become somewhat of a legend a century later. A Travelling Tablet Perhaps the greatest mystery of all, however, is where Valsin himself was originally buried. A survey completed in the 1930s notes the tablet to be located in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, Aisle 8-R, although it does not specify lot number. Today, Valsin’s tablet is located in Aisle 7-R. Unfortunately, the original cemetery records for 1826 do not specify lot number. While we may love Valsin’s immortal eulogy, his mortal remains may never be located for sure. One Hundred Years of Mistranslation Nearly 75 years after Valsin’s death, in 1900, the New Orleans Daily Picayune wrote a full-page piece on local cemeteries in honor of All Saints’ Day, November 1. This was a common annual occurrence in which newspapers would describe the scene at each cemetery, noting curious epitaphs or beautiful new tombs. With this article, Valsin’s memory was revived in a very peculiar way: On one old slab, almost defaced with age, is the inscription “Ci git un malhereuse qui fut victim de son imprudence. Verse un larme sur sa tombe, et un ‘De Profundis’ s’il vout plait,” por son ame. Il n’avait que 27 ans, 1798.” The translation reads: “Here lies a poor unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Drop a tear on his tomb and say if you please the Psalm, ‘Out of the Depths I Have Cried unto Thee, Oh, Lord’ for his soul. He was only 27 years old.[11] Three years later, on November 2, 1903, the Picayune printed the exact same paragraph in another All Saints’ Day article. This printing birthed two widely-repeated falsehoods regarding Labarre – that he had died in 1798 (the year he was born), and that the tablet had an additional line regarding a psalm, which it clearly does not. This misunderstanding would perpetuate itself, making scholars and authors truly the victims of their own imprudence. In 1919, a tourist brochure said of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1: “The inscriptions are in French, and many of them tell how he who sleeps beneath ‘fell in a duel, the victim of his own imprudence.[12]’” It is unclear if this is directly inspired by Labarre or perhaps another now-missing tablet. Unfortunately, even the most revered of New Orleans cemetery texts replicate to the Labarre myth. In one seminal 1974 book, the authors suggest again that Labarre’s is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, quoting the Picayune article. The text also muses that perhaps the poor fellow had died in a duel. From 1974 to 2004, three other publications cite this faulty article, each suggesting that it is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, and that the deceased had met his end in a duel. One insists that the tablet is long lost to history. All this time, André Valsin Labarre’s tablet has sit idly by as tour groups wind in and out of the cemetery aisles.

New Orleans cemeteries typically identify the owners of tombs by direct lineage. Through this lens, there are no descendants to claim care of the prodigal son’s tablet. Valsin’s son, Samuel Placide Labarre, married Emma Labranche in 1866. Their union produced one son, who Samuel named after his father, Valsin. Valsin Labarre died around 1890. There is no indication that he married or had children. Additionally, Virginia Conrotte remarried after Valsin’s death. She and her new husband, Daniel Gregoire Borduzat had at least four children. Unfortunately, the surname Borduzat appears nowhere in indexed cemetery records. If indirect relatives to Valsin Labarre remain, they have not reconnected with his burial place. Both the tablet to his memory and Valsin himself have become, in a sense, immortal for the most peculiar of reasons. Yet their fate remains suspended between the aisles of New Orleans' oldest cemetery, awaiting the next chapter in their story. [1] Stanley C. Arthur and George Campbell Huchet de Kernion, Old Families of Louisiana (New Orleans: Harmanson, 131), 98-104.

[2] Arthur and Campbell, 98. [3] William Reeves, De La Barre: Life of a French Creole Family in Louisiana (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1980), 79, 88. [4] Reeves, 88. [5] Reeves, 175. [6] Reeves, 119. [7] Probate inventory of André Valsin Labarre, New Orleans Public Library microfilm KR 308, Old Inventories, Vol. L, 1821-1832. [8] 1821 New Orleans directory, Louis Labarre, No. 14 Conti. [9] New Orleans will documents, New Orleans Public Library, VRD410, 1805-1833, Recorder of Wills, Vol. 4, 106. [10] La Courier de Louisiane, August 16, 1826, 2. Accessed via microfilm, New Orleans Public Library. Translation composite of a number of translations from French speakers, William Reeves, and Emily Ford. [11] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1900, 3. [12] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “In Old New Orleans,” from Travel, Vol. XXXII, No. 4 (Feb. 1919), 26. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

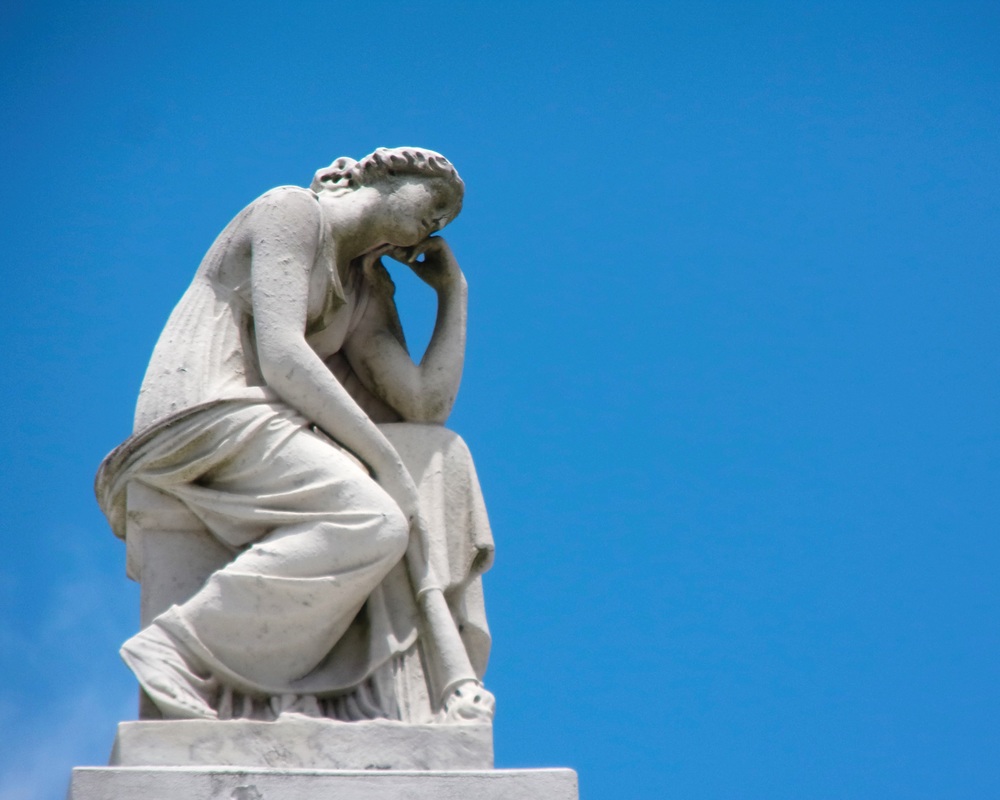

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly