|

As the weather cools down, cemetery managers and community groups look to living history performances to inspire support and interest in their historic landscapes. It’s that time of year again! The weather is cooling down, the pumpkins are in their patches, and our minds turn toward the ethereal, mysterious landscapes of cemeteries.

It’s also the time of year when a lot of preservation, heritage, and municipal groups hold annual cemetery fundraising events in the form of living history tours. Events like these connect the public with historic cemeteries in a unique way – visitors walk through the cemetery, often at night or twilight, and meet the “residents” of the cemetery. Through drama (and sometimes music), visitors can connect with the importance of the cemetery to local history and culture. Living history tours are also a whole lot of fun! Wherever you are in the South this year, there is a living history event in a cemetery near you. It might be Natchez City Cemetery’s annual “Angels on the Bluff” tour, a large-scale event that sells out every year, as does Oakland Cemetery’s “Spirits of Oakland” program in Atlanta. But it also might be a smaller event hosted by a local historical society. Check out the listings below to plan your cemetery visit – it makes a great date night or family outing.

0 Comments

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

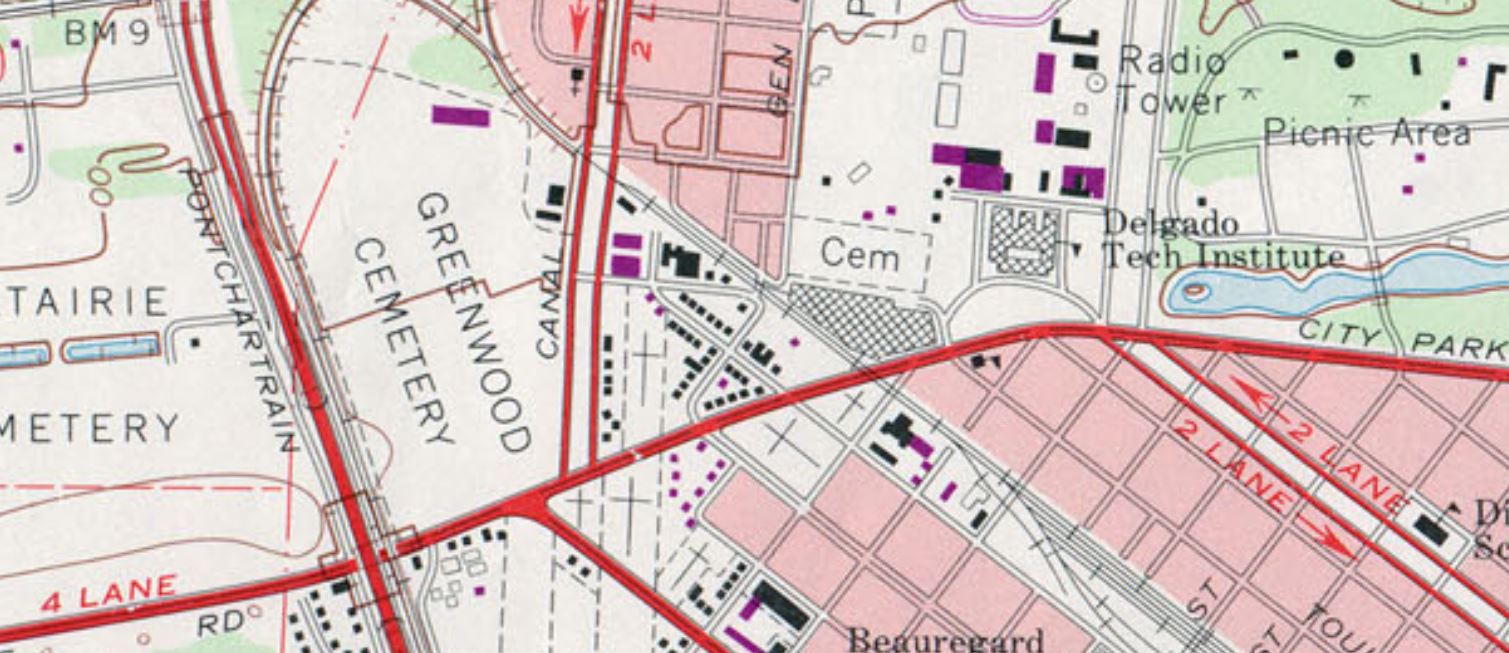

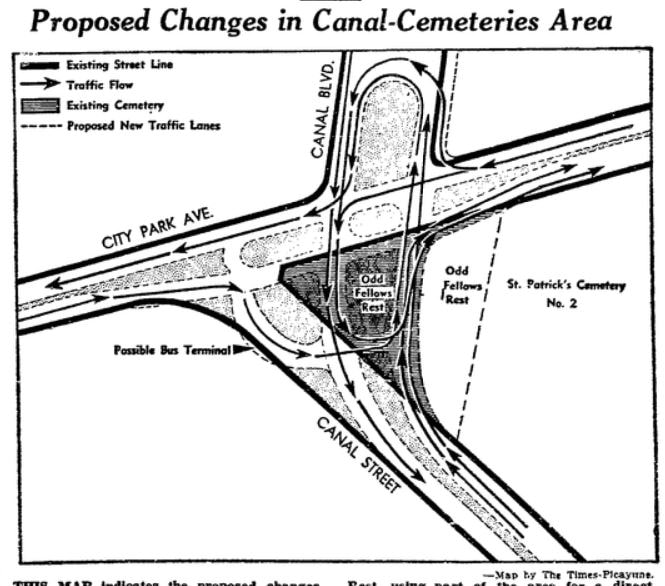

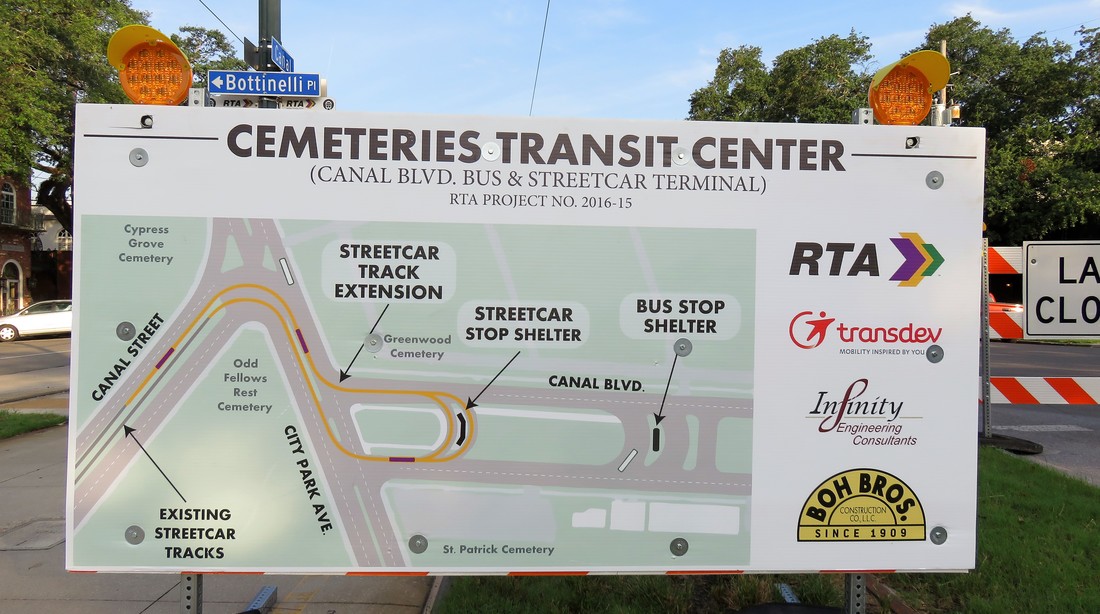

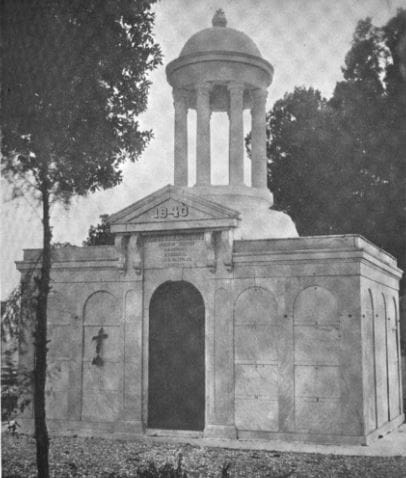

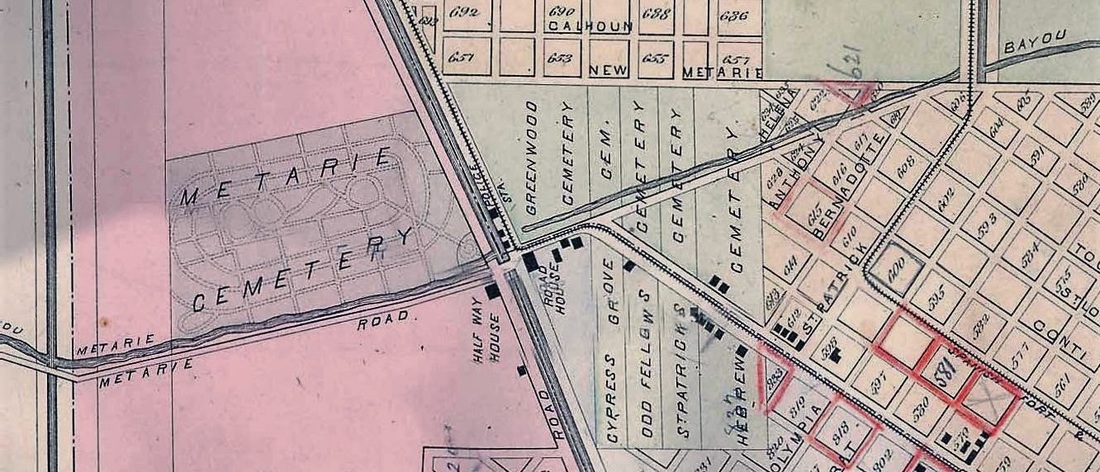

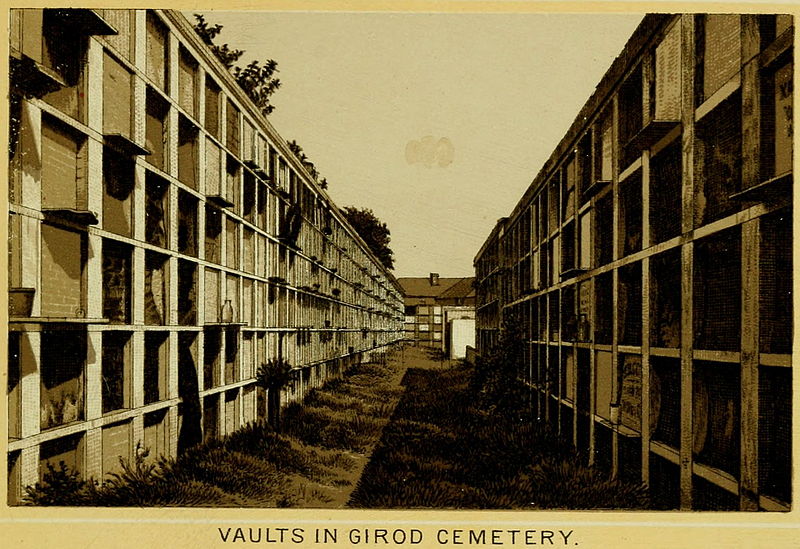

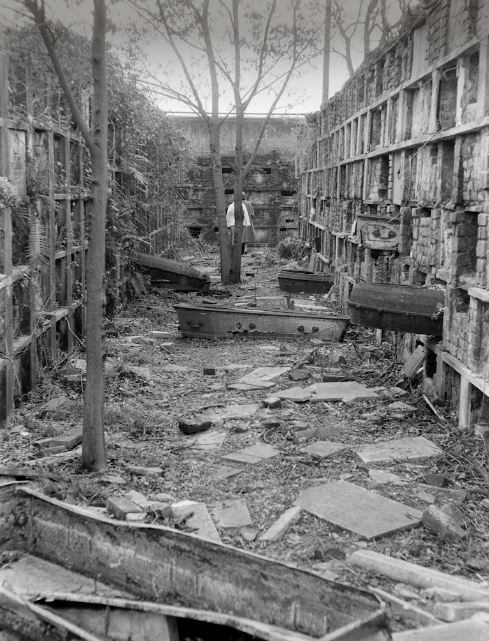

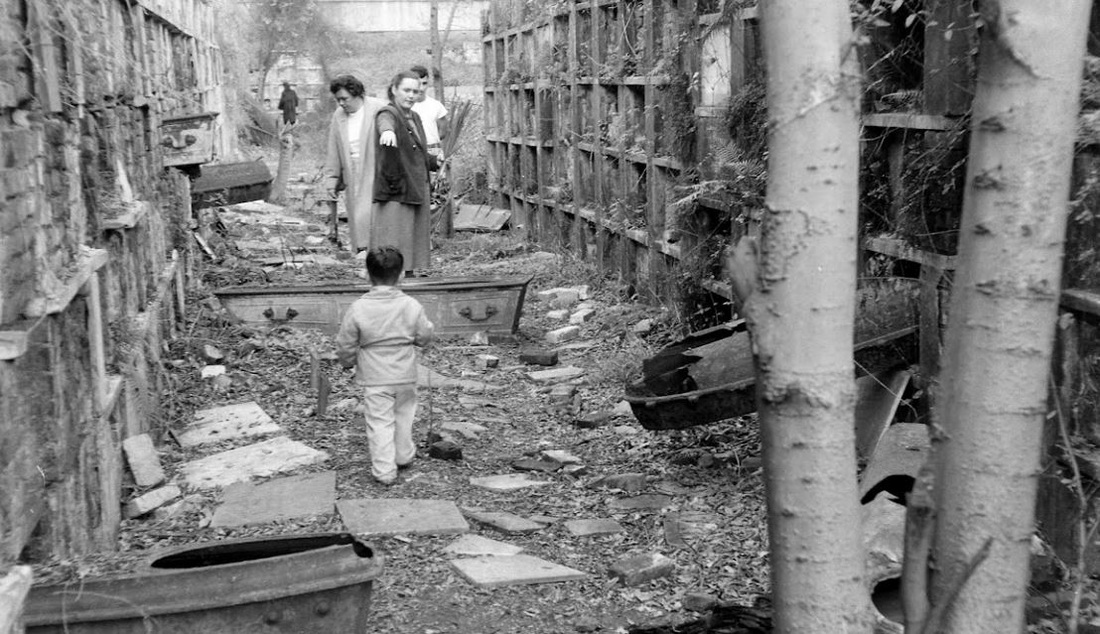

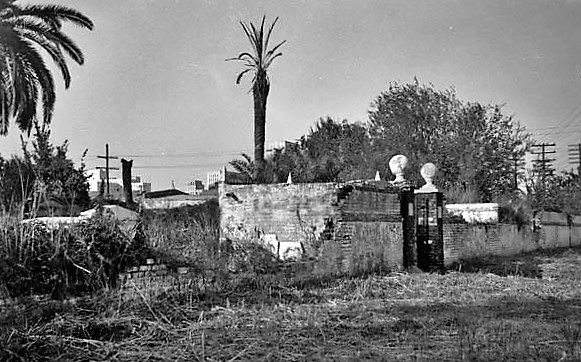

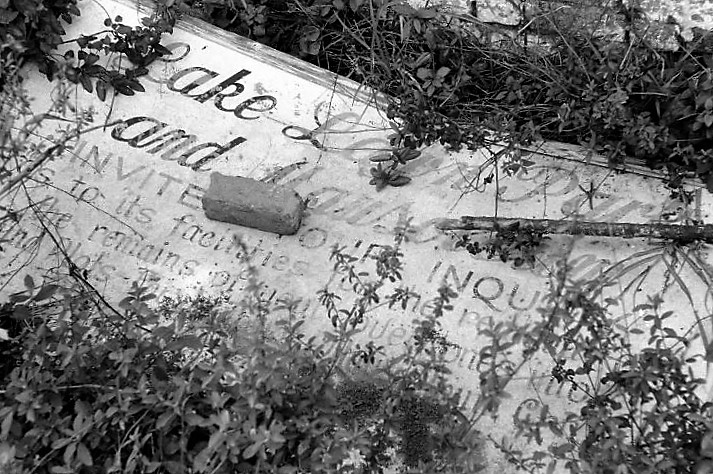

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb. This is the fifth and final part in a five-part series on the historic landscape of City Park Avenue and Canal Street, and its associated cemeteries. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. To start at the beginning of this series, find Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here, and Part Four here. By the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue had undergone a century of extraordinary change. Where once Bayou Metairie meandered westward past acacia trees and a pastoral ridge, now City Park Avenue coasted across the New Basin Canal to become Metairie Road, past the grand monuments of Metairie Cemetery, and into Old Metairie. Where once the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove stood tall over an undeveloped landscape, now cars rumbled past the monuments and walls of Greenwood Cemetery and Odd Fellows Rest. Jazz blared from the Halfway House beside the New Basin Canal through the 1920s, until the House was converted into an ice cream parlor in 1930.[1] Bayou Metairie had slowly been filled in to accommodate City Park Avenue. To the east, Delgado Central Trades School (now Delgado Community College) was opened in 1921. Beside Delgado, Holt Cemetery remained the municipal potter’s field for New Orleans, but in 1940 the cemetery gained a new neighbor – the Higgins Boat Plant. PTs, Higgins, and the Cemetery Andrew Higgins (1886-1952) is known today in New Orleans as the man who brought the shallow-bottom PT and “landing craft, vehicles, personnel” or “LCVP” boats to the Allied effort in World War II. LCVP boats were used extensively in the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1945, leading then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower to say in 1964 that Higgins had “won the war for us.” Before World War II, Higgins had gotten his start designing shallow-bottom boats that performed well in the Louisiana bayous and other waterways beset by submerged obstacles. But by the late 1930s, Higgins produced new designs that not only could achieve amphibious landings in shallow waters, but were also equipped with ramps to allow swift disembarkation upon landing. These qualities made Higgins Boats imperative to the war effort. In 1940, Higgins Industries constructed a $1.5 million boat-building facility in the least expected of places: far from water, along City Park Avenue, and beside Holt Cemetery. Ever known for his enterprising spirit, Higgins’ City Park plant became the “world’s largest boat manufacturing plant housed under one roof.”[1] The plant took advantage of the Southern Railway line that cut northwesterly across City Park Avenue, beside Masonic Cemetery No. 2. Boats would be manufactured at the City Park plant, which employed thousands of people, and shipped to Lake Pontchartrain for testing. The booming wartime production of the plant left the operation bursting at the seams. Said historian Jerry Strahan of Higgins’ need to expand: “The back of the shipyard was adjacent to Holt Cemetery. Higgins decided to enlarge the plant ‘knowingly and willingly’ by preempting an unused portion of the cemetery grounds. The plant was increased until 40 percent of the new facility was constructed on property to which Higgins held no title, a problem that was unresolved as late as 1947.”[2] Photos of the plant and adjoining Holt Cemetery can be found here under photographs numbered 14 and 21. As early as November 1945, the loss of massive wartime governmental contracts hit the Higgins plant hard. The property was put up for sale.[3] The building at 501 City Park Avenue would have myriad uses over the next thirty-five years – it was a Piggly Wiggly grocery store in 1948, offices for Georgia Pacific Corporation in 1959, and part of the building was used as an art warehouse in 1964.[4] From the 1960s through the 1970s, a van and storage company conducted business in the old plant. In 1972, the building was demolished - its walls, beams, floors, and other items sold for salvage.[5] Finally, in 1982, Delgado Community College opened the Arthur J. O’Keefe Administration Building at 501 City Park Avenue.[6] The architecturally intriguing building remains in the same capacity to this day. In 1964, Holt Cemetery would cease to serve as New Orleans’ potter’s field. The city of New Orleans, under coroner Frank Minyard instead leased a lot from Resthaven Cemetery in New Orleans East for this purpose. This section of Resthaven continues to serve as New Orleans’ indigent burial ground. The American Way of Death After the close of World War II, industries which had boomed forward industrially and technologically looked inward for domestic uses of their innovations. Higgins Industries attempted to this very thing: selling Higgins-designed watercraft for private uses. While to contemporary readers it may seem strange, the same phenomenon took place in the funeral and cemetery industries. Moreover, the clientele of these industries had changed: they were more prosperous, more mobile, and had different values. For 1950s Americans, death was to be confronted with more discretion, privacy, and modernity than had been the case for previous generations. The cultural boom of the 1950s held an inherent disdain for the old-fashioned. This trend is often best exemplified in the scorn held for Victorian architecture during this period. Modern Americans sought urban renewal to wipe away old landscapes. In New Orleans, such sentiments manifested in the rapid construction of community mausoleums, establishment of “memorial park” style cemeteries like Garden of Memories, and the destruction of Girod Street Cemetery. Girod Street Cemetery was established in 1822 at the foot of Girod Street near Liberty Street. By the mid-1950s, the cemetery was bounded by the New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, part of a neighborhood seen as old, blighted, and an obstruction to progress. After repeated attempts by the cemetery’s owner, Christ Church Cathedral, to resurrect the cemetery both architecturally and functionally, it was expropriated by eminent domain to the federal government and the City of New Orleans. The cemetery was demolished in 1957. Girod Street Cemetery was located far from the Canal Street cemeteries, but it held certain cultural and architectural ties to other Protestant-dominated cemeteries like Cypress Grove and St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery. As the process of demolition began, the Huber family which had assumed ownership of St. John’s Cemetery in the 1920s, jockeyed for the contract to relocate the Girod Street remains. This competition involved multiple cemetery craftsmen-turned-cemetery owners and would not be the last time a cemetery operator competed for business with his peers. At the same time Girod Street Cemetery was being demolished, cemeteries at Canal Street and City Park Avenue were modernizing. The first inklings of cemetery stoneworkers turning to cemetery operation began in the 1910s and 1920s. For example, in 1910, stonecutter Albert Stewart assumed ownership of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street, acquiring it from the Suarez brothers. The Huber family had gained ownership of St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery in the 1920s – and by the 1930s, began construction on Hope Mausoleum, the first community mausoleum in New Orleans. Community mausoleums had gained some traction in the United States beginning in the 1890s and increasingly so in by the time of the Great Depression. In this era, the idea of a large, single-structure facility for burial appealed to cultural ideals of mutual benevolence (indeed, many belonged to fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows) and frugality. In New Orleans, these cultural desires were often met instead with society tombs – large, multi-vault structures within larger cemeteries. Society tombs were New Orleans’ version of community mausoleums, which reflected a more northern aesthetic. It is, then, not surprising that the Huber family gained ownership of German Lutheran St. John’s Cemetery and erected Hope Mausoleum around the historic burial ground. The development almost appears as an extension of St. John’s, Girod, and Cypress Grove Cemetery’s tendency to reflect non-Francophile aesthetics. In the early 1930s, Hope Mausoleum opened, a modestly Art Deco edifice encased in polished marble and touting itself as, “The Modern Way of Burial.”[8] The postwar boom of the 1950s saw a second heyday for community mausoleums, but these mausoleums suited newer cultural norms. The era valued opulence and modernity, sleek, state-of-the-art materials and a dearth of filigree and detail. The funeral and cemetery industries, rising into a new period of lobbying professional organizations, consolidated costs, and property accumulation, responded in kind. Indeed, author Jessica Mitford in her 1963 indictment of the industry, The American Way of Death, compared the contemporary funeral industry to the car industry of the same age: overloaded with space-age fins and baubles.[9] Thus, the new community mausoleum was meant to be an expression of modernity and opulence, and a doing-away with the stodgy funereal rituals and trappings of the past. Into this new market rose the children of Albert Stewart – Frank Sr. and Charles Stewart. Under their business, Acme Marble and Granite Company, the Stewarts purchased land adjoining the north boundary of Metairie Cemetery and set forth to construct a community mausoleum for the age. Completed in 1958, Lake Lawn Mausoleum would be the “the ultimate in modern burial,” with “paneling of rich mahoganies, carpeted floors, custom-built furniture, and rare plants and flowers.”[1] Lake Lawn would be the anti-Girod Street Cemetery. Historic photos suggest that Lake Lawn advertised within the walls of Girod Street, declaring that burials removed from the old Protestant cemetery could be moved to a thoroughly modern location. In fact, the engineer of Girod Street Cemetery’s demolition, Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, did just that. The contents of the Story family mausoleum, relatives of Mayor Morrison, were moved to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum in May of 1956. In the end, though, Hope Mausoleum would gain the contract to re-inter the white burials from Girod Street Cemetery. In accordance with contemporary segregation laws (even in death) Providence Memorial Park in Metairie would receive the African American burials from Girod Street. The torchbearer of urban renewal, Mayor Chep Morrison, would himself in death become part of the struggle between rising cemetery entrepreneurs, and the clash of new and old New Orleans cemetery culture. Shortly before his death in 1957, entrepreneurial monument man Albert Weiblen, who by this time had expanded his business to owning entire quarries in Georgia, purchased the entirety of Metairie Cemetery. His widow Norma maintained this enterprise after Albert’s passing, and when Mayor Chep Morrison perished in a tragic airplane accident in 1964, a standoff ensued between old Metairie Cemetery and modern, neighboring, Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Mayor Morrison had, as mentioned previously, moved his family’s remains from Girod Street Cemetery to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Yet while the new mausoleum was modern, Metairie Cemetery had been the lauded resting place of New Orleans mayors, governors, and Mardi Gras kings (nine, eleven, and more than fifty, respectively[1]). Metairie’s position in New Orleans culture was to be the hallowed resting place of power in all its forms. Presumably to preserve this reputation, Norma Weiblen called Morrison executor William H. Lindsay, Sr. on May 24, 1964, offering the Morrison family very steep discounts on a new tomb in Metairie Cemetery if they would consider moving Mayor Morrison’s burial there from Lake Lawn Park. She added that Lake Lawn Park was a “stinkpot,” and that she “knew [Metairie Cemetery] was where [Morrison] belonged.”[2] Years later, the matter would result in a lawsuit. Morrison was buried in Metairie Cemetery and, in 1969, Stewart Enteprises purchased Metairie Cemetery, renaming the joined properties “Lake Lawn-Metairie Cemetery.” The modernization of historic cemeteries at the end of Canal Street was fueled by the spirit of an era – and a struggle for space. By the 1950s, many of the cemeteries in the area were more than a century old. Furthermore, the city of New Orleans and the suburb of Metairie had grown tightly around them, leaving no room to expand. Community mausoleums were a practical way to capitalize on sellable space. Metairie Cemetery had made such a venture – filling in one of the cemetery’s lagoons to construct Metairie Mausoleum in 1958. In 1964, the various parish-owned Catholic cemeteries in New Orleans would be consolidated under the new New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. Ten years later, the Calvary at the rear of St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1 would be demolished to construct Calvary Mausoleum. In 1969, the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association would open Greenwood Mausoleum. The Jewish cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would also reorganize ownership. In the late 1950s, the Hebrew Burial Association would form to assume ownership of Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. With religious restrictions against above-ground burial, the cemetery instead appears to have expanded toward Bernadotte Street in this time, where today a section of modern, 1950s granite monuments stands. In 1973, conservative congregation Chevra Thilim established Chevra Thilim Memorial Park in a small triangle of land bounded by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, and Iberville Street. In 1999, Chevra Thilim merged with another congregation to form Shir Chadosh congregation, who retains ownership of the memorial park-style cemetery. Canals, Streetcars, and Automobiles Within cemetery walls, local stonecutters became sales agents and marble increasingly gave way to increased use of granite. No longer the city’s potter’s field, Holt Cemetery became a burial ground for the families of those already interred therein. Outside the cemeteries of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, water and soil gave way to concrete and pylons The New Basin Canal, in service since 1838 and arguably the heart of the cemeteries landscape, was by the 1950s no longer fit for industrial use. As with Bayou Metairie before, the canal was filled in and repurposed for automobile use. In 1958, a new overpass was constructed for City Park Avenue traffic to traverse over the canal, but its use would be short lived. By 1962, sections of the canal nearest to Lake Pontchartrain were filled in and became West End Boulevard. At the end of the wide boulevard’s neutral ground, a civil defense bunker was constructed as a station of command for government in the event of nuclear war. The bunker has been abandoned since the late 1990s, but remains present on West End Boulevard near Robert E. Lee Boulevard. Finally, in 1968, plans that had begun in the 1950s with Mayor Morrison came to fruition and a superhighway was constructed to connect Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Pontchartrain Expressway, part of Interstate 10, was constructed above the filled-in New Basin Canal – replacing high levies and deep water with tall pylons and dipping underpasses. Increased automobile traffic was met with increased automobile infrastructure, but one seemed to continually outpace the other. The roadways as they were in 1968 were complex and disconnected: Canal Boulevard met City Park Avenue, which met Canal Street in a dog-leg which already vexed motorists. The triangular lot of Odd Fellows Rest formed this dog-leg, and in the 1960s, civic eyes turned to eliminate the obstacle. The (sort-of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest As early as 1948, New Orleans’ City Planning Commission recognized the “dog-leg” problem.[13] As automobile drivers increasingly used Canal Boulevard and Canal Street as a commuter route to and from the city, the multiple turns needed to achieve this route caused traffic congestion. While the commission desired nothing more than to connect the two streets, Odd Fellows Rest cemetery had sat firmly between them since 1849. By 1963, the plan to “bypass” Odd Fellows Rest was revived. The Planning Commission announced in August of that year that it sought to purchase “the entire Odd Fellows Rest on the downtown river side of the intersection of Canal st. and City Park ave. and a very small portion of the adjoining St. Patrick No. 2 cemetery.”[14] The City would purchase the cemetery, relocate the remains interred therein, and demolish the remainder in order to connect Canal Street and Canal Boulevard. Like its neighboring cemeteries, Odd Fellows Rest had struggled to transition from the nineteenth century to the postwar era. In 1950, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) hired stonecutter Armand Rodehorst, Sr. as the new superintendant of the cemetery.[15] Rodehorst had worked for fifteen years across the street at Greenwood Cemetery, as a laborer for Samuel Gately. In joining Odd Fellows Rest, he was striking out on his own.[16] Rodehorst developed Odd Fellows much in the same way that other cemeteries had done. He built multi-vault tombs to sell piecemeal and constructed modern, cast-concrete tombs. In 1958, however, Rodehorst died in his home at the age of 56.[17] The economic future of Odd Fellows Rest was left without a helmsman. Thus, by 1963, the Louisiana Grand Lodge was positioned to sell the cemetery property, although “not interested in partial relocation, but in total relocation of the cemetery.”[18] City Council, Mayor Victor Schiro, and the Planning Commission agreed to fund the project. Property on City Park Avenue near Delgado Community College was selected, which the City would purchase and gift to the Odd Fellows for transfer of the cemetery’s remains. City Council purchased a lot “bounded by City Park Avenue, Conti Street, Virginia Street, and St. Louis Street” for the purpose.[19] Yet in a twist of fate perhaps unique to New Orleans and its local politics, a private firm learned of the land purchase and beat the City to the punch. The purchaser, Plaza Towers, Inc., bought the property and, in turn, offered to gift it to the City in exchange for another parcel of municipal land located on Howard Avenue and South Rampart. Unlike the City Park Avenue property, which was purchased only as leverage, the Plaza Towers firm needed the Howard Avenue property in their construction project: the forty-five story Plaza Tower building designed by Leonard R. Spangenberg, Jr. & Associates. This obvious power grab left City Council “irate.”[20]

In August of 2005, flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina effected even the cemeteries of Metairie Ridge. Metairie Cemetery lost its administrative building near the cemetery entrance, and untold tombs were damaged. In 2008, state-owned Charity Hospital Cemetery was converted into a memorial to the lives lost in Hurricane Katrina. The property was excavated and analyzed by archaeologists, and large vaults were erected, clad in reflective black granite. The unidentified and unclaimed remains of 86 hurricane victims were interred at this site, which each year is visited and dedicated on the anniversary of Katrina’s landfall. To learn more about the inspiring, harrowing, and touching story of the Katrina Memorial, please read this fantastic piece by Mary LaCoste in the Louisiana Weekly: “Remembering the Katrina Memorial that Almost Wasn’t.” The Last Days of the Halfway House The Halfway House, once positioned tranquilly along the New Basin Canal but by 2005 instead wedged beside the Interstate 10 overpass, was also damaged in the storm. Beginning in the 1840s as a place of rest and refreshment for carriages en route to Lake Pontchartrain, later a restaurant and jazz hall, then an ice cream parlor, the building was purchased in the 1950s by Orkin Pest Control Company. Abandoned by Orkin in the mid-1990s, by 2005 the property was derelict, its roof partially collapsed. The Halfway House was the property of the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association, held by a long-term lease by the city of New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina, plans were set in motion to convert the adjoining property – once Albert Weiblen’s marble shop – into the new 911 Communications Center for the city. It looked as if the Halfway House would be demolished to make way for a parking lot. Even before 2005, an organization called the Jazz Restoration Society worked with the FCBA and City to secure ownership of the Halfway House, with the goal of restoring it to a restaurant and music hall. Years of infighting, pushing and pulling, and negotiations in the city finally ended in 2009, when the building was declared a landmark and the Society was given permission to step in. But, much like the land deal between the City and Odd Fellows Rest, another shoe had to drop. When an environmental assessment was conducted at the Halfway House, soil tests found that forty years of pesticide storage and disposal left the property unsalvageable by even the best intentions. Despite years of fighting to save the Halfway House, it was demolished in 2010. Conclusion As of this writing, the current road construction project at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is on-schedule and should be finished in one week. Streetcar lines are laid, sweeping across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard. Archaeological assessments and relocation of remains from the cemetery beneath Canal Boulevard have taken place. Soon, the intersection will assume its most recent form, in a place that has held so many forms for one hundred and eighty years. In this series, we have seen this place conform to cultural changes, urban expansion, technological innovation, war, and peace. It is a testament to how imperceptibly dynamic New Orleans cemeteries are – that we can walk through them and feel tranquility and stillness, when in reality they’re shifting, conforming, losing and gaining things that will be held precious by future generations. And there’s even so much we’ve left out! Left out was the Perseverance Lodge No. 13 society tomb in Cypress Grove, hit by lightning twice in the late twentieth century and recently reconstructed by FCBA. Left out was the flower shop on Canal Street beside Cypress Grove, once a hub for chrysanthemums and roses shuttled off to the cemeteries, by the 1990s derelict, and demolished in 2016. The merger of Stewart Enterprises, Inc. with Service Corporation International in 2014 merits its own thousand words on the industrialization of funeral and cemetery industries. Uncountable changes have taken place in this tiny colony of cities of the dead. This retrospect, more than anything, then, has been an overture to recognizing how very important those aspects of our cemeteries which have survived all of this. From Cypress Grove to Chevra Thilim Memorial Park, from Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum to Holt Cemetery, it is impossible to appreciate these relics too much. [1] Samuel Charters, A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 257.

[2] Jerry Strahan, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats that Won World War II (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1994), 49-50. [3] Ibid. [4] “For Sale: Two of the Modern Higgins Industrial Plants and Clinic in New Orleans,” Times-Picayune, November 19, 1945, 17. [5] Times-Picayune, April 11, 19; Times-Picayune, October 6, 1959, 27; Times-Picayune, April 5, 1964, 71; Times-Picayune, February 10, 1964, 45. [6] “Higgins Shipyard,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1972, 44. [7] “Congratulations Delgado,” Times-Picayune, March 4, 1982, 19. [8] “The Modern Way of Burial” was Hope Mausoleum’s official slogan from the 1930s through the 1950s. For example, “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, May 2, 1935, 2; and “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, January 26, 1958, 2. [9] Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 20-21. [10] “Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, October 3, 1954, 15; “Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum – A Report on Progress,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1951, 10. [11] Henri A. Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, Inc., 1981), 108. [12] “Details on Switch of Morrison’s Burial Site Revealed,” Times-Picayune, May 5, 1966. [13] “End to Canal ‘Dog-Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1. I would like to recognize and thank Michael Duplantier for sharing resources and information contained in the (sort of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest section. [14] Ibid. [15] “Odd Fellows Cemetery,” Times-Picayune, December 26, 1950, 41. [16] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1935, Vol. LXI (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1935), 1171; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1938 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1938), 933; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1949 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1949), 1209. [17] “Business, Civic Leader Expires: Rodehorst Rites will be Held Today,” Times-Picayune, September 16, 1958. [18] “Accord on Canal Street ‘Dog Leg’ Plans Possible,” Times-Picayune, November 7, 1963, Section 2, 6; “Lodge to Help on Street Link,” Times-Picayune, August 20, 1963, 7. [19] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [20] “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, June 3, 1964, 1. [21] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [22] Edward J. Branley, New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line (Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 95. Beginning July 2017, New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) will be executing a significant construction project at the intersections of Canal Street, City Park Avenue, and Canal Boulevard – an area known simply as “the Cemeteries” by streetcar riders and New Orleaneans in general for more than a century. The construction project will extend the Canal Streetcar across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard in a turnaround that will streamline public transportation (see the diagram above). This is first successful attempt at creating a streetcar turnaround at this intersection, which is notoriously confusing and historically jammed with traffic, owing to an odd dog-leg where Canal Boulevard and Canal Street meet City Park Avenue. Fifty years ago, RTA made a similar attempt to connect Canal Boulevard and Canal Street – although that earlier design necessitated the demolition of Odd Fellows Rest Cemetery. Fortunately for New Orleans cemetery heritage, this plan was scrapped and the cemetery was saved.[1] This tangled intersection of New Orleans thoroughfares, joined with the Pontchartrain Expressway (Interstate 10), is the site of a dozen different New Orleans cemeteries ranging in founding dates from 1840 to 1973, and ranging in background from elite city of the dead to humble potter’s field. The intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is an essential crux of New Orleans history in almost every way. It is a heart of metropolitan development and architectural expression without compare. Over the next month, Oak and Laurel is taking a look at the history of the Canal Street cemeteries and their environs, beginning with the history of the land itself.

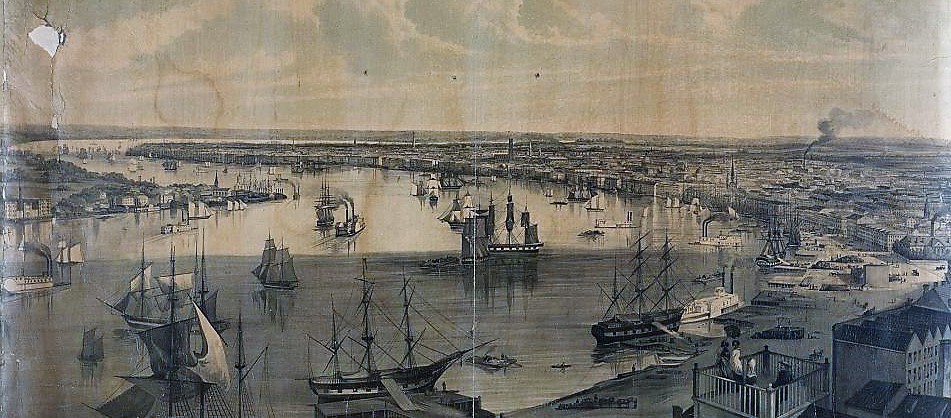

Until this time, commercial navigation between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain utilized Bayou St. John and the Carondelet Canal. The Carondelet Canal was dug in 1794 and extended Bayou St. John to what is now Basin Street – named so for the turning basin located there. The Carondelet or “Old Basin” Canal had disadvantages. Specifically, its age made it less practical, and its location meant its primary beneficiaries were Creoles and other established residents of the former colonial city.[2] Competition between the old French-speaking order and the American interests that populated the city after the Louisiana Purchase motivated investment in a new canal. In 1831, the New Orleans Canal and Banking Company was founded by the Maunsell White and Beverly Chew with the backing of the state of Louisiana. The company was formed with the specific goal of establishing a “canal from some part of the city or suburbs of New Orleans, above Poydras street to the Lake Pontchartrain.”[3] Construction on the New Basin Canal began in 1832, although a terrible cholera epidemic held up its progress that year. The construction of the New Basin Canal was overwhelmingly fueled by the labor of Irish immigrants. Beginning in the 1830s and intensifying in the next decade, migration from Ireland to New Orleans helped make the Crescent City the second-largest port for immigrants in the country. Newly-arrived Irishmen typically came from agricultural backgrounds and sought manual labor in their new city. Tragically, the enormous labor demand and barbaric conditions of hand-digging the New Basin Canal caused thousands of deaths. Sources refer to daily deaths in the trenches from illness and exhaustion, the fallen laborer buried in the soil along the canal as work progressed. The construction of the New Basin Canal defined the Irish experience in New Orleans.[4] The New Basin Canal began at a turning basin along Triton Walk, approximately the present location of the Union Passenger Terminal in the Central Business District. It extended northwest near what is now Carrollton Avenue and turned more northerly from there, meeting Lake Pontchartrain at what is now West End Boulevard. If this route sounds vaguely like the route of Interstate 10 from the Crescent City Connection to the I-10/610 merge, that’s because the Pontchartrain Expressway very closely replaced the New Basin Canal route in the mid-twentieth century.

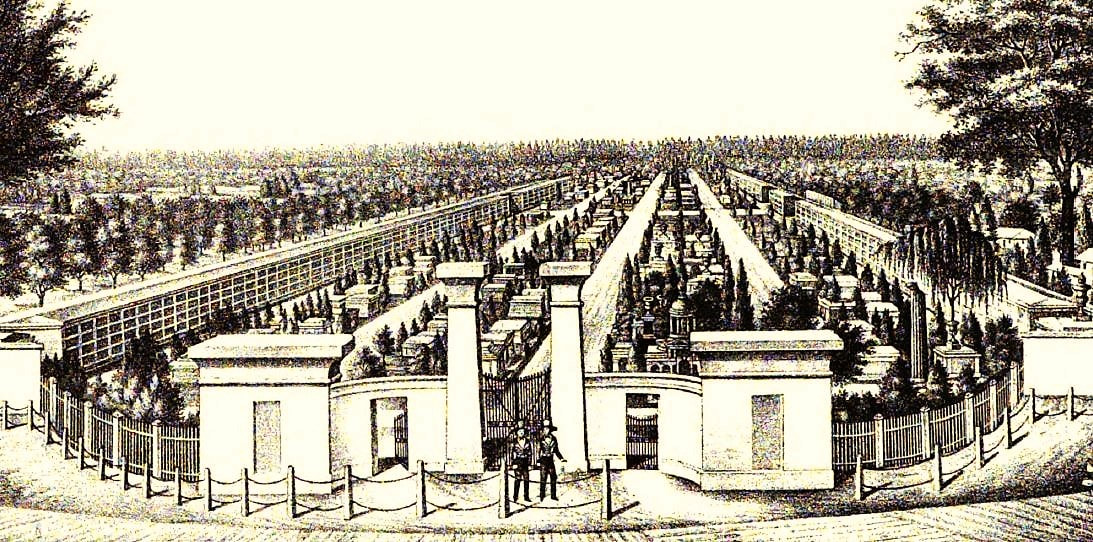

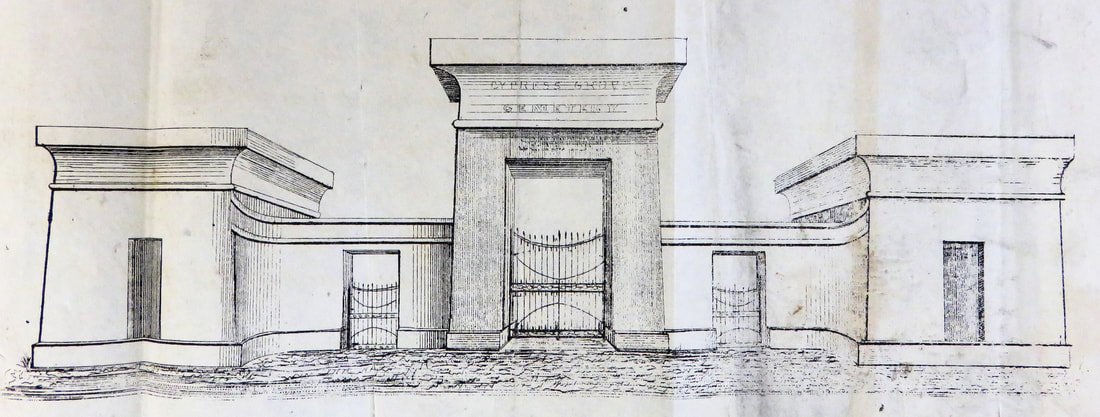

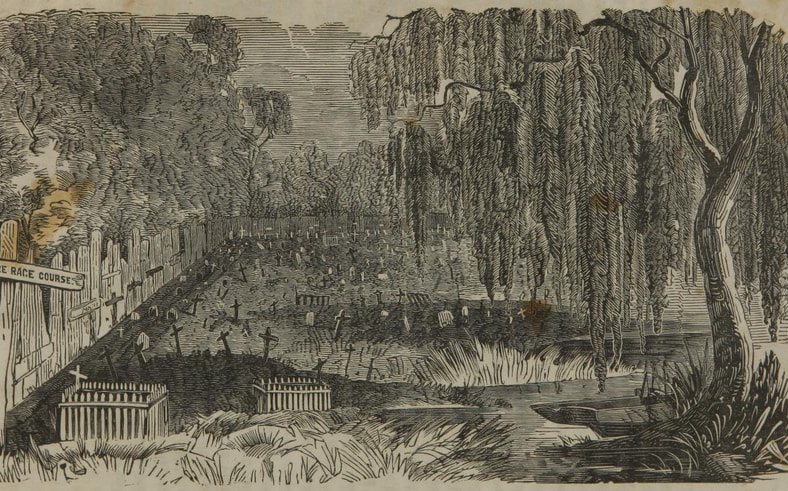

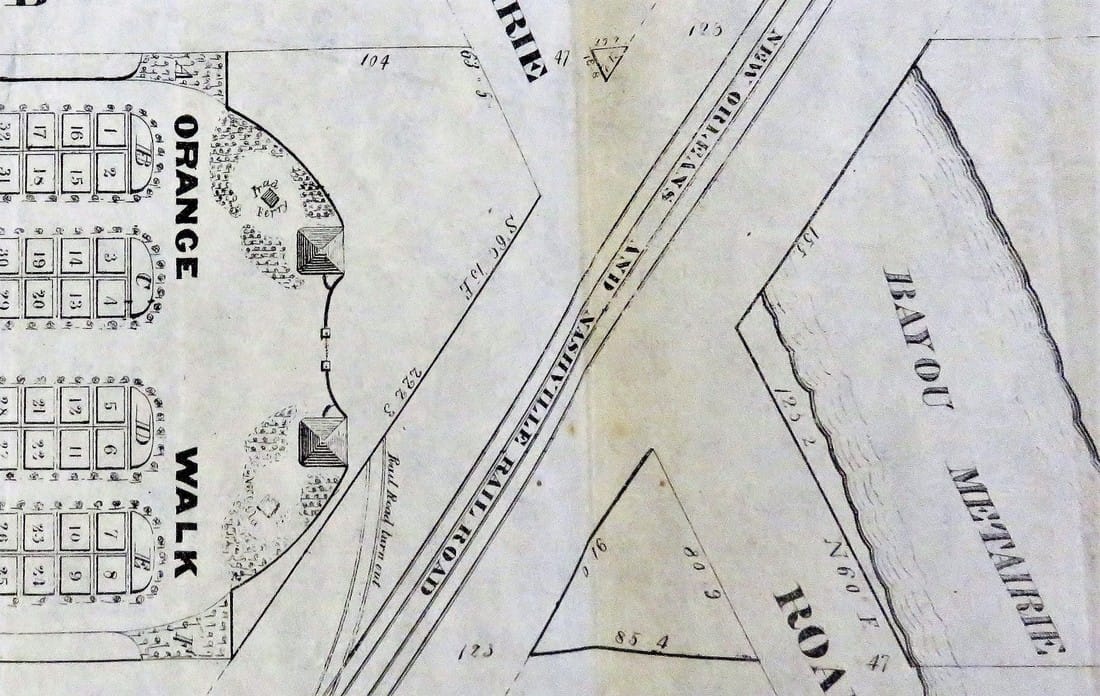

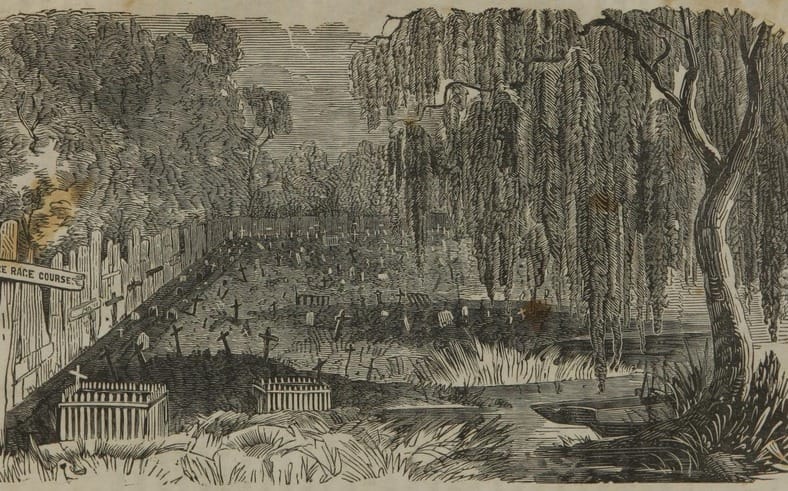

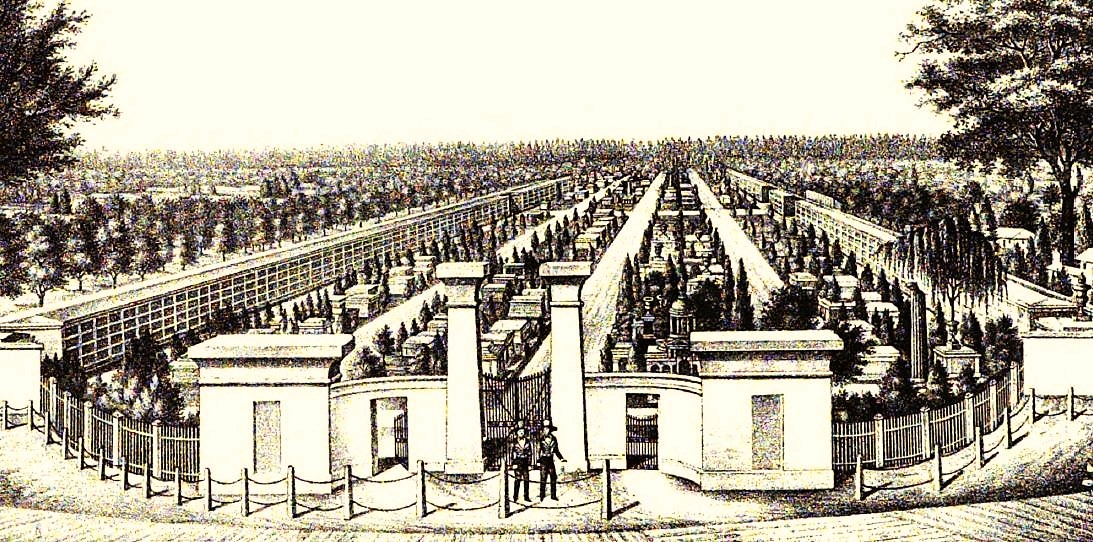

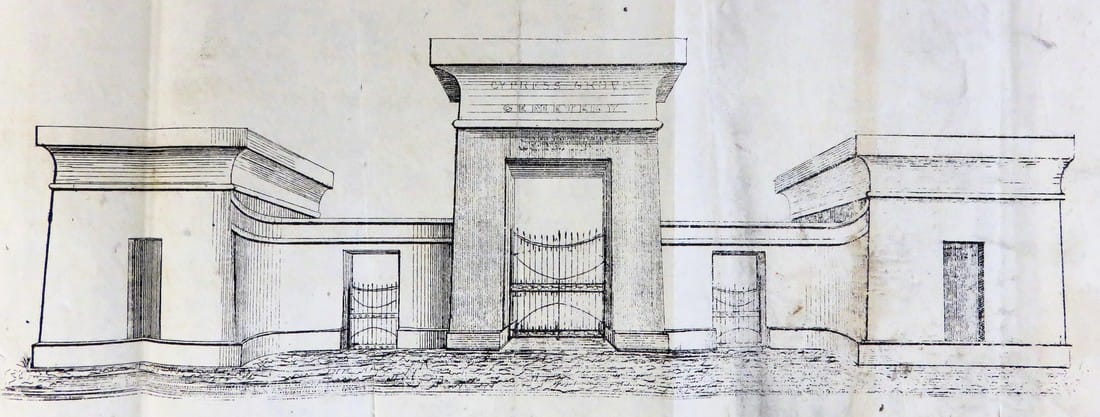

While newcomers to the city found in the Shell Road and New Basin Canal a rural retreat possibly reminiscent of home, these same people from the Northeast, from Ireland, from Germany, and elsewhere, found no cemetery in New Orleans that could be so reminiscent. For the next sixty years, these people would shape this area into such cemeteries.[5] 1840: Cypress Grove Cemetery From the time of the Louisiana Purchase through the 1840s, immigrants from all over poured into New Orleans. As they brought their bodies and livelihoods, they brought their culture and traditions. From Creoles of color from San Domingue, New Orleans gained the shotgun house. As for the thousands of immigrants from the Anglo-Protestant North who came to New Orleans, New Orleans gained from them wire-cut Pennsylvania brick, Anglo-American concepts of landscape design, and the idea of the rural garden cemetery. The rural cemetery movement arose in the northeast in part from the contemporary expansion of cities. Advances in industrialization within the urban landscape created in city-dwellers a longing for the countryside. Furthermore, this same industrialization advanced the American middle class in such a way that recreation was newly defined. Inspired by English landscape design, the rural cemetery was the predecessor to the public park – in fact, Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed one such cemetery in California. This shift in the appearance and purpose of cemeteries coincided with many American cultural movements like Romanticism, the definition of the middle class, and the “beautification of death period.” Northern Americans who moved to New Orleans were inspired by what they saw at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and many more. These were cemeteries that were designed instead of planned, with undulating pathways that strolled past weeping willows and reflecting pools. This was the rural cemetery movement, a great leap in the history of cemeteries that would change the American perception of death forever. This contrasted deeply with the Francophile and Creole cemeteries that had developed in New Orleans to this time – densely packed “cities of the dead” with few if any landscape features. St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 was not planned out by lots or aisles and instead haphazardly developed into the necropolis it became. After St. Louis No. 1, Girod Street Cemetery, St. Louis No. 2, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 (1822, 1823, and 1833, respectively) were planned into square and aisles, but remained cemeteries set in urban landscapes. The cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would be a departure from this context. On April 25, 1840, the first cemetery at the intersection of Canal Street and Metairie Road was officially opened. Cypress Grove was owned and operated by the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association (FCBA) and, although the cemetery would be open to all burials, it would be dedicated to the memory of New Orleans’ volunteer firemen. The dedication ceremony of Cypress Grove included a march of nearly one thousand firemen, clergy, and prominent citizens marching through downtown New Orleans, each wearing mourning bands and a few carrying urns of the ashes of their martyred comrades. The procession boarded the Nashville railroad at the foot of Canal Street and rode to the end, where the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove’s entrance would have stood almost completely alone within the undeveloped landscape. Among the martyrs honored that day was Irad Ferry, the “first martyr,” who perished in the line of duty on New Year’s Day 1837. Originally buried in Girod Street Cemetery, Ferry’s remains were relocated to Cypress Grove as the cemetery’s first burial, beneath a marble sarcophagus topped with a broken column which was designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and constructed by stonecutter Newton Richards. In a nearby tomb constructed for this purpose, the remains of eleven additional firemen were buried.[6]

It would seem almost superfluous to set for the advantages of this rural cemetery. The rapid growth of our city has already encroached upon the tombs of its fathers, and the sacred relics of the dead have been compelled to give way to the cold and selfish policy of speculators, and the intrusion of business; and the solemnity of the grave yard is disturbed by discordant shouts of merriment, and the baleful proximity of the dissolute.[8] (To learn more about Cypress Grove’s history, check out our blog post “Lost Landscapes of Cypress Grove,” Part 1 and Part 2) Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 or Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2 Cypress Grove Cemetery may have extended across Bayou Metairie and through what is now Canal Boulevard. It is true that a cemetery was once present in this space. However, the cemetery is referred to in records as both “Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2” and “Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2.” This potter’s field, which records suggest was dominated only by below-ground burials of the indigent, is referred to in at least one record as belonging to the Firemen’s Benevolent Association, but leased by Charity Hospital for the burial of deceased patients.[9] Over the next century, Cypress Grove No. 2 would accept thousands of indigent burials and become an on-again, off-again bone of contention in this funerary landscape.[10] Next week, we will explore the 1840s as new cemeteries are founded, namely St. Patrick’s, Dispersed of Judah, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest. [1] “End to Canal ‘Dog Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1; “Planners Revive Canal St. Cut-off,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1963, 17; “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, July 3, 1964; “City Abandons Cemetery Suit,” Times-Picayune, December 12, 1972, 9.

[2] Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2008), 30, 135. [3] T.P. Thompson, “Early Financing in New Orleans: Being the Story of the Canal Bank, 1831-1915,” Publications of the Louisiana Historical Society, Vol. VII (1913-1914), 24. [4] Laura D. Kelley, The Irish in New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2014), 32-36. [5] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 132-133, 139-140; David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 44-46. [6] Thomas O’Connor, ed. History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FMBA, 1890), 70-71. [7] “Firemen’s Celebration in New Orleans,” Galveston Daily News, March 6, 1869, 1. [8] Firemen’s Charitable Association, Report of the Committee of the Firemen’s Charitable Association, on the Cypress Grove Cemetery (New Orleans: McKean, 1840), 4. [9] Henry Rightor, Standard History of New Orleans, Louisiana (New Orleans: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900), 265. Rightor’s 1900 history refers to this cemetery as Charity Hospital No. 2. [10] Peter Dedek, The Cemeteries of New Orleans: A Cultural History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 61, 77. New Orleans is home to dozens of cemeteries, each with its own character and history. Among these many burial and interment grounds are the influences of world cultures, human expressions of grief, and iterations of architecture that, in one way or another, are recognized as significant on small and large scales. Some are more appreciated than others. Some have been lost entirely from the landscape, such as St. Peter Street Cemetery, Girod Street Cemetery, or Gates of Prayer Cemetery on Jackson Avenue. Yet among these recognized and unrecognized burial grounds, there is one nearly always omitted, even though people walk by it and photograph it every day. Tucked behind St. Louis Cathedral and often overshadowed by the looming statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, is the final resting place of nineteen French navy men who died in 1857 and were re-interred at this place in 1914.

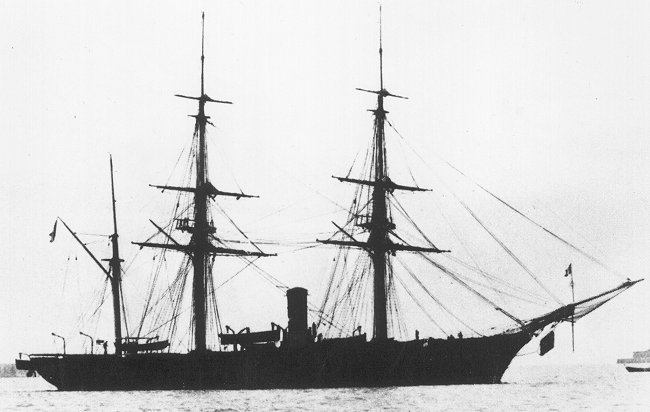

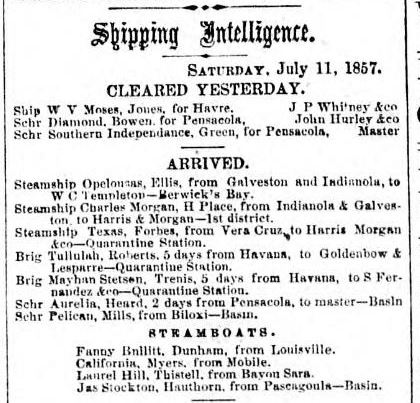

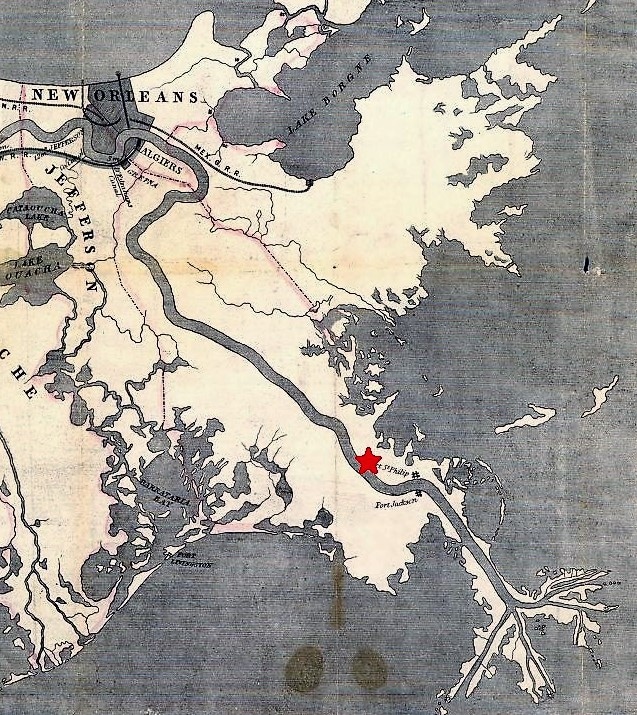

In the years following this harrowing incident, the surviving crew of the Tonnerre and their families in France, as well as French naval authorities, sought to memorialize the lost sailors. A monument was erected in the Quarantine Station cemetery in August 1859. The marble obelisk would not be seen for long, however. The Quarantine Station was soon relocated, with the former site abandoned. The monument would not be rediscovered until 1914, when Andre Lafargue endeavored to reclaim it.[3] The tale of the Tonnerre, its crew, and its monument, highlights so many historical aspects of the mid-nineteenth Caribbean and Atlantic world. It is a story of memorialization and reclamation, of the interactions between cultures and nations, and of the management of public health in this time. In this post, we seek to unpack some of these curious aspects of the monument that rises so subtly from behind St. Louis Cathedral. The Ship Tonnerre The Tonnerre is referred to in historical documents as both a corvette and an aviso or “advice ship.” While there appears to be some distinction between the two (and we don’t presume to call ourselves naval historians) – for example, avisos are customarily smaller than corvettes – documents consistently refer to the Tonnerre as a ship assigned the duty of relaying messages between larger naval commands. The four-gun Tonnerre was a steam-powered vessel, propelled by a paddle, and was inducted into service by the French Navy at Indret in 1838.[4] By 1850, the French Navy had about a dozen such first class “advice boats,” including five constructed of iron (Le Mouette, Le Heron, Le Eclaireur, Le Requin, and L’Epervier), although the Tonnerre was not constructed of iron. By 1857, the Tonnerre and its crew had already completed service in the Crimean War (1853-1856) in which an alliance of European powers fought Russia for influence over the Black Sea and Middle Eastern. Lieutenant Clement Maudet, who came to command the Tonnerre, fought with the French Foreign Legion in Crimea, earning a medal for his bravery. Many of the other sailors aboard the Tonnerre served in this conflict before being dispatched to the Caribbean. The presence of the Tonnerre in the Caribbean also highlights the colonial and military interactions in the Caribbean and Atlantic world at the time. The Tonnerre was charged with relaying messages between Vera Cruz and Havana (a role the ship would serve through the late 1850s).[5] The ship’s mission likely related to French economic and political interests in Mexico, which Emperor Napoleon III viewed as critical to Latin American trade access. French intervention would escalate to full on invasion in 1861, and later the unsuccessful installation of Hapsburg emperor Maximilian I. It was in this conflict in 1863, that Lieutenant Clement Maudet would die of wounds acquired in the Battle of Camerone.[6] The Tonnerre was the fifth ship of the French navy to bear this name. The first French Naval Tonnerre was the British HMS Thunder, captured in 1696. The Tonnerre under Maudet’s command in 1857 was retired in 1878. The French Navy currently operates the eighth Tonnerre, placed into active service in 2006. The Crew The Tonnerre had an original crew of eighty sailors, including a doctor (who died of yellow fever at the Quarantine Station), sailors, ensigns, stokers (steam engine operators), chefs, and mates. Eighty of whom contracted yellow fever either in Mexico, Louisiana, or Cuba. Thirty of these seamen died. Two of the chefs aboard the Tonnerre who perished in 1857 appear to have been of Italian descent: Giovanni Carletto and Jean Janotti. Ages of the men who died aboard the Tonnerre are not listed.

In 1853, for example, the fever was presumed to be caused by “miasmas” or “bad air” (a theory derived from Enlightenment thought), and thus the City burned torches of pitch and discharged cannons in order to disperse airborne maladies. By the 1850s, the Sanitarian movement had begun to marginally influence public health, focusing on cleanliness of public spaces and the removal of fetid water. Quarantine Stations were present in most eastern seaboard cities by the early 1800s. In New Orleans, the necessity of such stations was frequently debated and they were often decommissioned. In many cases, New Orleans merchants were staunch opponents of quarantine. Such systems, they said, disrupted commerce and were thus unacceptable. Their arguments appeared validated when, on occasion, epidemics broke out despite the presence of quarantine stations – likely due to the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti)’s fondness for sheltering in ship cargo holds. Incidentally, however, 1857 was not a significant epidemic year for New Orleans. As the Tonnerre had no intention of docking in the City en route to Havana, the condition of this one ship’s crew posed little danger of epidemic to the Crescent City.

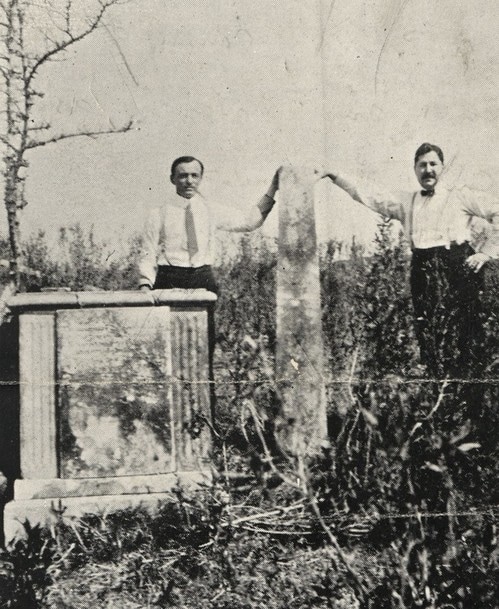

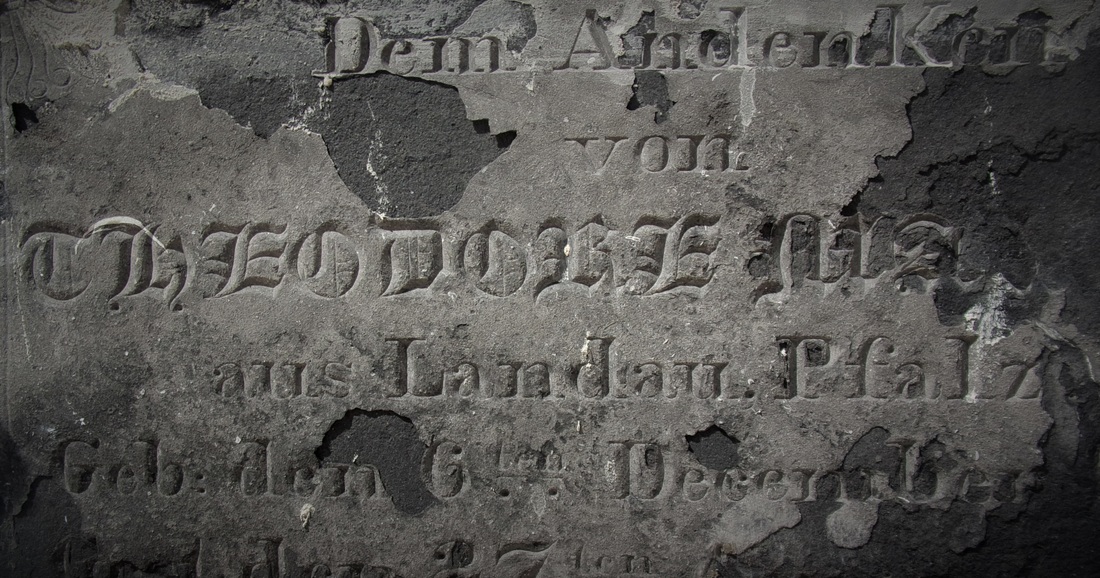

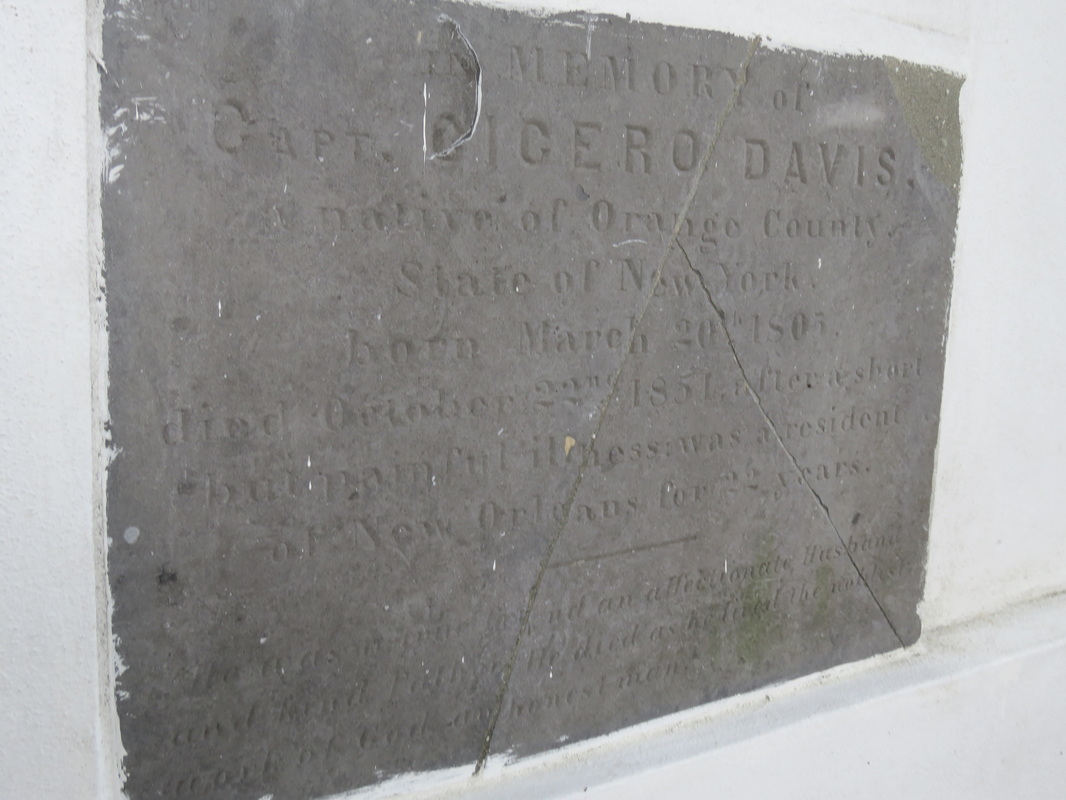

The Quarantine Station would be abandoned after the 1860s, after the US Government established an additional Quarantine Station at Ship Island, Mississippi. In 1880, the Louisiana Board of Health reported on the condition of the Ostrica-area Station, the grounds “open and roamed over by cattle.[10]” It described a complex of several buildings: a fever hospital, a pox hospital, a medical residence, a boatmen’s quarters, and a warehouse. Said the board of the process of disinfection at the hospitals: The process of disinfection now employed consists of burning sulphur in iron pots. These pots are placed in tubs containing water. This method is liable to the grave objection that there is, in many cases, and especially during rough weather, danger of firing the ship.[11] In this report, the Board of Health appears to be investigating the feasibility of placing the Station back into service, although no evidence suggests this happened. However, the report documented the enduring presence of the Tonnerre monument: The graveyard of the Quarantine Station is located about 200 feet to the rear of the Fever Hospital, and is surrounded by a rude fence and covers about three-fourths of an acre. Marks of about one-hundred graves can be discerned by the inclosure [sic], which are thickly covered with tall grass, brambles, and shrubs. There is only a solitary marble monument, which bears the following inscription: "A la mémoire de Trente Marins, faisant partie de l'équipage de l'avito vaisseau de la Marine Imperiale le Tonnerre, décède à la Quarantaine de la Nouvelle Orléans en Août, 1857. Erige par l'Odre de S.E. L'amiral Hamelin, ministre de la Marine de l'Empereur Napoléon III.”[12] The Monument Thanks to donations from the families of surviving Tonnerre crewmen, a marble monument was installed at the Quarantine Station in 1859. Unfortunately, the craftsperson that designed and built it is unknown. Photos from the monument’s recovery indicate that it was originally a marble-clad box tomb, with fluted corner pieces and a marble slab atop which the monument’s obelisk and urn were fixed. This style of memorial was typical of 1850s high-style cemetery architecture in both New Orleans and France. Derived from sarcophagus designs, similar monuments can be found in the cemeteries of Montparnasse (France) and St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, although less modified versions are visible in the upriver parishes. The Tonnerre monument was described intact by the Louisiana Board of Health in 1880, even though the Quarantine Station cemetery had become derelict. Andre Lafargue shares a similar recollection from his youth, seeing the monument ascending from the brush as he traveled the river. Lafargue notes that at some time between 1880 and 1914 the obelisk fell in a hurricane.[13] The Quarantine Station long abandoned, without intervention the Tonnerre monument would have sunken beneath overgrowth and debris. Yet in 1914, Andre Lafargue, who at that time served as the attorney for the Comité du Souvenir Francais, came across in the French Society records documentation of the Tonnerre monument. In an effort that proved fruitful if not also tremendous and risky, Lafargue chartered a boat from Buras to Ostrica, bringing with him the vice French consul general at the time, Andre Lacaze, and their wives.[14] Trudging through the brush with only a vague recollection of where the cemetery and Quarantine Station once stood, the party discovered the remains of the monument: We finally came to a spot, near a tree of greater dimensions than the others, and there found traces of former habitations, and all of a sudden our feet struck a pile of bricks and pieces of marble and we knew, after examination of the fragments, that we had finally found the spot where the cemetery stood long years before and where the monument had been built. The ladies, highly elated by the discovery, were very helpful in picking up various pieces of the pedestal and we finally located the obelisk, the main section of the most important part of the monument, and the gracefully draped urn. The urn had been wrenched from the top of the obelisk and the latter had broken into two pieces in its fall to the ground, after the pedestal and the foundation had been undermined by the elements and the rough usage of time.[15] Over the course of subsequent trips to the site and through partnerships with groups like the Societe de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle, the monument was packed away and sent upriver to New Orleans. Despite the contestations of local undertakers that recovery of the remains of the 19 seamen who died at the Quarantine Station would be impossible, Lafargue and his crew set out to disinter each one. Each body was laid beneath the flag of France during disinterment, then shrouded and placed together in a metallic casket, where a single French flag was draped across them. In an additional gesture of reverence, the party uprooted a small tree from the cemetery and placed it in the coffin with the remains, to be re-planted at the new monument site.[16] The monument was reconstructed by New Orleans stonecutter and tomb builder Albert Weiblen. Weiblen built a burial vault atop which the monument would sit and bordered with a Georgia Creole marble coping wall. This vault forms a tumulus structure and simultaneously elevates the monument. Weiblen’s skill in reconstructing the monument is remarkably evident: it is difficult to determine which elements of the monument are replacements and which are original. But some clues are visible: one inscribed tablet is of a slightly different type of marble, and is inscribed with a pneumatic tool, whereas the other inscribed faces of the pedestal have smaller, hand-carved lettering. It appears as if the monument itself may have been slightly downsized, it’s dimensions shaved away to remove damaged or unsalvageable elements. A small bronze plaque was installed at the front of the coping by De Lucas Monument Company at the cost of $13.[17] Since its rededication, the Tonnerre monument has survived a few more hurricanes, and an instance in the 1930s in which an inebriated driver crashed through the gates of the Cathedral garden and toppled the obelisk. But for the most part the monument (and the remains therein) have known peaceful repose, quietly situated between St. Louis Cathedral and Royal Street, so often escaping notice. [1] Andre Lafargue, “The Little Obelisk in the Cathedral Square in New Orleans,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan. 1945), 329.

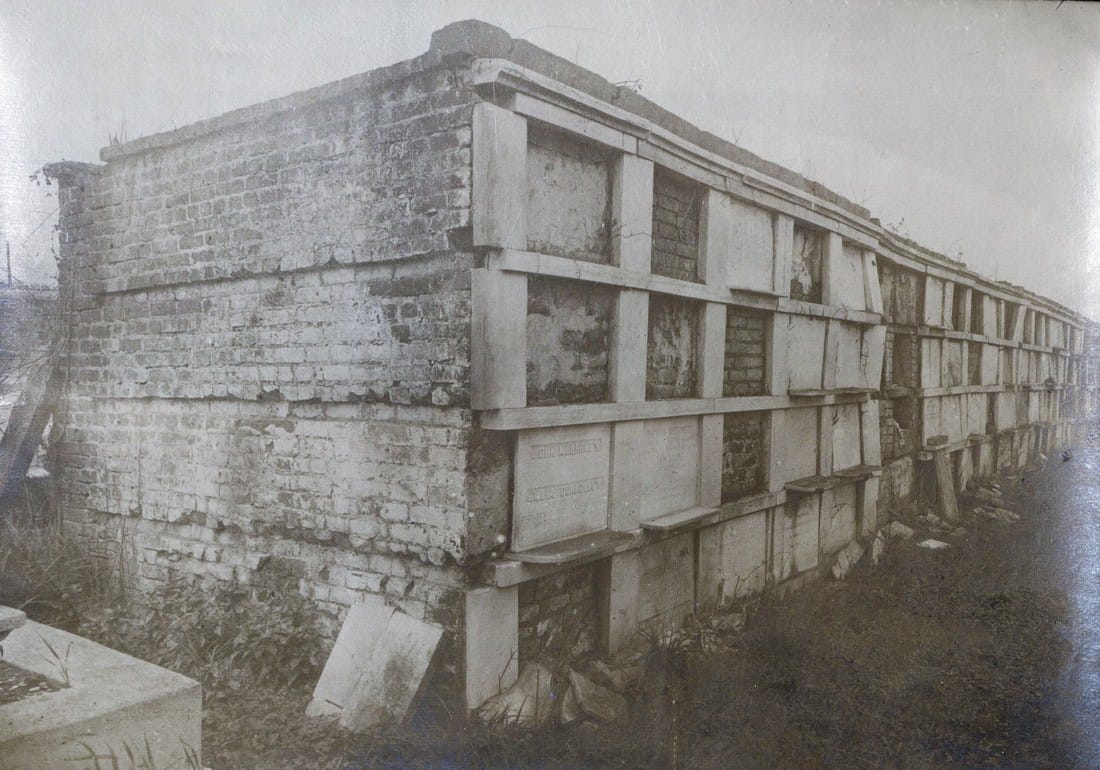

[2] Every history of the Tonnerre’s trials at the Louisiana quarantine station omits the commander’s first name. Based on other histories of the French Navy in the Baltic and Mexico, and other statistical data, the commander of the Tonnerre was most likely Clement Maudet (1829-1863), French Legionnaire, who would die later in Mexico during the Battle of Camarone, part of the Second French Intervention. [3] Ibid., 333-336. [4] John Fincham, A History of Naval Architecture, to which is prefixed an introductory dissertation on the application of mathematical science to the art of naval construction (London: Whittaker and Co., 1851), 408. [5] French war steamer Tonnerre embarks from Havana to Mexico, Daily Picayune, October 21, 1857; French war steamer Tonnerre returns to Havana, Daily Picayune, December 14, 1857. [6] This is an extremely generalized recapitulation of colonialism in the Caribbean in the 1850s. For further reading see: The Second French Intervention in Mexico, The French Intervention in Mexico and the American Civil War, and if all of this is too complicated or frustrating, just check out this fun comic. [7] Henry Rightor, Standard History of New Orleans, Louisiana (New Orleans: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900), 211-213. [8] John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 60; Joy J. Jackson, Where the River Runs Deep: The Story of a Mississippi River Pilot (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1993), 55; Alcee Fortier, Louisiana: Comprising Sketches of Parishes, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form, Vol. 2 (Century Historical Association, 1914), 337. Jackson notes quarantine stations located at Cubit’s Gap (around 1910) and a post-1920 station at the lower end of Algiers. Andre Lafargue describes a quarantine station at Pilot Town, twenty miles downriver from Ostrica, by 1914. [9] John Duffy, ed. The Rudolph Matas History of Medicine in Louisiana, Vol. II (Binghamton, New York: Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., 1962), 185-186. [10] Joseph Jones, M.D. Report of the President of the Board of Health of the State of Louisiana for the Year 1880, 14. The report also notes the success of quarantine measures for that year, including the removal of the bark Excelsior, bound from Rio de Janiero, to Quarantine, which “certainly freed the city of New Orleans from the infected crew, and in the opinion of a portion of at least of the medical profession, preserved the citizens from an epidemic.” [11] Ibid., 18. [12] Ibid., 15. [13] Andre Lafargue, “The Little Obelisk in the Cathedral Square in New Orleans,” 336. [14] John Smith Kendall, A.M., History of New Orleans, Vol. III (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1922), 1149. [15] Ibid., 338. [16] Ibid., 336-342. There is no indication that this tree remains in the garden behind St. Louis Cathedral. [17] Receipt from De Lucas Monument company to Comite Francaise, Andre Lafargue papers, MSS 552, Folder 10, Tulane Louisiana Research Collection. Part Two of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. Find Part One here. In the 1840s, Cypress Grove Cemetery developed into the landscape its founders envisioned: tree-lined and populated with tombs of the finest order. It also gained company as St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest were all established between 1840 and 1850. There at the corner at what is now Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Cypress Grove was part of a pastoral scene: barges floating up Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal, visitors strolling the gardens at the Halfway House, and rail cars pulling up right to the cemetery gates, unloading mourners and the bodies of the mourned.[1] Between its founding in 1840 and the turn of the century, Cypress Grove would become the final resting place of many famous and infamous New Orleans characters. Northern-born transplants to the city would combine New Orleans tomb architecture with the styles and materials they were accustomed to. Firemen would memorialize their fallen brethren within the cemetery’s marble-clad walls. Much of the incremental detail of the cemetery at its height, though, has weathered away from its present-day appearance. It’s easy to miss this historic garden cemetery for its modern lack of trees. But with historic research and a keen eye, it’s possible to rediscover Cypress Grove’s historic grandeur. Firemen, Northerners, and Protestants Cypress Grove was the first fraternal cemetery in New Orleans. All other cemeteries founded up to 1840 belonged either to the Catholic parishes (except Protestant Girod Cemetery, belonging to Christ Church Cathedral) or to each respective municipality (i.e. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1). Many other fraternal organizations, including other firemen’s organizations, would found their own cemeteries over the course of the nineteenth century. Cypress Grove was not intended for the exclusive burial of firemen. It served all New Orleanians seeking burial, if they could purchase a plot, and many who could not. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (present-day Canal Boulevard) was contracted by the City of New Orleans for indigent burial, even after Charity Hospital Cemetery was established in 1848.[2] While Catholics in New Orleans had many cemeteries from which to choose, Protestants had only Girod Street Cemetery and the municipal cemeteries. Perhaps it was simple economics that caused so many Northern-born Protestants to buy property in Cypress Grove. It may also have been caused by cultural interaction between the Firemen (many of whom were also non-native New Orleanians) and others who joined them as newcomers in the Crescent City. In any case, the great majority of historic burials in Cypress Grove denote birth in northern climes such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and others. The Firemen’s Charitable Association fell into this market easily. Stonecutters whose work featured mostly in Girod Street Cemetery, such as long-time Girod Street sexton Horace Gateley, executed tombs and tablets in Cypress Grove as well. Gately himself, who drowned in at Isla del Padre, Texas in 1867, is buried in adjoining Greenwood Cemetery. The FCA even advertised in-ground burial in Cypress Grove. While in-ground burial occurred in nearly every cemetery in the city, FCA was the only cemetery owning body to advertise it – plainly appealing to newcomers with a distaste for Continental-inspired above-ground tombs.[3] When Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957, Cypress Grove became a de facto artifact of what the Protestant cemetery may have looked like. Simpler, sarcophagus-style tombs with accents placed more on great obelisks and sculpture than on Greek acroteria or Baroque scrollwork dotted the aisles of both Girod and Cypress Grove. What few photos of Girod Street Cemetery remain even suggest a few duplicate tombs between both cemeteries: including the now headless and armless tomb statue and tomb of Henrietta Sidle Davidson (died 1881) and another tomb in Girod Street. Philadelphia brick, New Hampshire granite, and other Anglo-inspired tastes contributed to the budding landscape of Cypress Grove.

Mr. [S.T.] Jones placed a closely sealed bottle in the box, containing the constitution and list of members of this efflisient [sic] company, the daily newspapers of the city, and the various coins of the country. This was also embedded in mortar, the cover put on, and the whole covered with solid masonry, upon which the corner stone was laid. The beauty of the day, the solemnity of the occasion, and the mournful memories engendered by the scenes around, all contributed to give the ceremony a peculiar interest.[5] The tomb of Perseverance Lodge No. 13 dominated the entrance of Cypress Grove Cemetery then as it does now – a large terra cotta cupola with ionic columns and a cast-iron finial at its dome was constructed atop the tomb roof. At the center of its primary façade, an entrance was likely constructed which was enclosed by cast-iron doors. Above this door were marble brackets and a Classical pediment. The tombs of Philadelphia Fire Engine and Eagle Fire Company were tucked into the front corners of the cemetery. Each built identically, with marble-clad masonry and large urns and finials, they were each enclosed with iron gates, each within the line-of-sight of the Irad Ferry monument. Masterpieces in Marble and Granite Other societies in addition to fire companies would build their tombs in Cypress Grove, most notably the Chinese tomb and Baker’s Benevolent Association tomb. But Cypress Grove would make its mark in the number of great family tombs that populated its aisles. The sarcophagus tomb is one of the most notable artifacts of funerary architecture in New Orleans cemeteries, and in Cypress Grove this was no different. Built of brick and clad in marble pilasters, cornicework, and sculptural elements, the sarcophagus tombs of the McIlhenny, Davidson, Johnston and Walker tombs are examples of the dozens of this burial type found in Cypress Grove. Built by stonecutters like Anthony Barret, James Reynolds, and Newton Richards, they represented the English-speaking stonecutter’s take on a burial style often associated with Creole artisans. The French-speakers were present in Cypress Grove, as well. Sarcophagus tombs by signed by Florville Foy are present beside the work of New Orleans-born Jewish stonecutter Edwin I. Kursheedt. Renowned French-born cemetery architect J.N.B. de Pouilly designed two of the best-known tombs in Cypress Grove: those of Maunsel White and Irad Ferry (constructed by Monsseaux and Richards, respectively).

The only remaining example of this style of historic tomb construction lies not in Cypress Grove but in Metairie Cemetery – the Duverje family tomb, constructed between 1808 and 1820 and moved from the family cemetery in Algiers in 1916, retains such acroteria. They are the last of their kind in New Orleans cemeteries. Then and Now After 1945, New Orleans cemeteries underwent a seismic shift in management, industry, and trade. The monument industry had been slowly becoming a national affair managed by large companies – a shift that reached New Orleans after World War II. Over the years, most cemeteries abandoned the employ of the cemetery sexton who traditionally cared for the grounds on a daily basis. Stonecutters, who had often served as sextons, adapted and became cemetery owners and dealers of nationalized products. Technology changed the way tombs were built, repaired, and maintained. This shift affected every cemetery in New Orleans. In the Catholic cemeteries, it led to the consolidation of parish burial grounds into the incorporated New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. In municipal cemeteries, it meant a transfer of management to overstretched city departments that cared for publicly-owned buildings and parks.[7] In the fraternal cemeteries, it meant a consolidation of duties and a new focus on sellable space to accommodate budget shortfalls.[8] With population movement to the suburbs and elsewhere, tombs were less likely to be cared for by their owners. With no sexton to manage the landscape, small issues with tombs became larger problems, often solved in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Storms like Camille, Betsy, and Katrina flooded Cypress Grove Cemetery, killing many of the surviving trees. Those who entered the monument trade after 1950 were much more familiar with new technologies than old materials. Old problems, then, were solved in new ways. In the 1960s, when the marble facing of the extensive wall vaults at Cypress Grove began to sag away from their brick substrate, the decision was made to remove the marble instead of repair it. When landscaping tumuli was too labor intensive, the sod was stripped from their structures, leaving cement-patched, igloo-like bodies behind. Herbicides like RoundUp were selected to replace arduous mowing, damaging masonry and causing grassy root structures to erode, leaving deep ruts which can destabilize walls and tombs. Alternately, trees which lent such a rural feel to Cypress Grove eventually overgrew their root structures, tipping walls and capsizing tombs. All the while, the responsibility of families to care for and repair their own cemetery property became anachronistic in an era of new innovations and perpetual care. The cultural forces that created Cypress Grove had transformed, with the role of the fraternal society somewhat supplanted by the rise of Social Security and insurance companies; the rural cemetery now firmly at the edges of the metropolis. New Orleans cemeteries in general are prized for their historic value, but the value of their maintenance and preservation may exceed that interest from many sides. Yet Cypress Grove remains, its Egyptian columns rising above Canal Street and City Park, where once the bayou and the railroad met. It may be difficult to see it, but with a conscientious eye and a little history, its lost landscapes can be found. [1] “Passenger and Freight Barges on the New Canal,” Daily Picayune, January 1, 1846, 4; Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louis Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Press, 2004), 30-35; At least one duel also took place in front of Cypress Grove’s gates, between former state senator Waggaman and a former New Orleans mayor Prieur, Daily Picayune, March 11, 1843, 2.

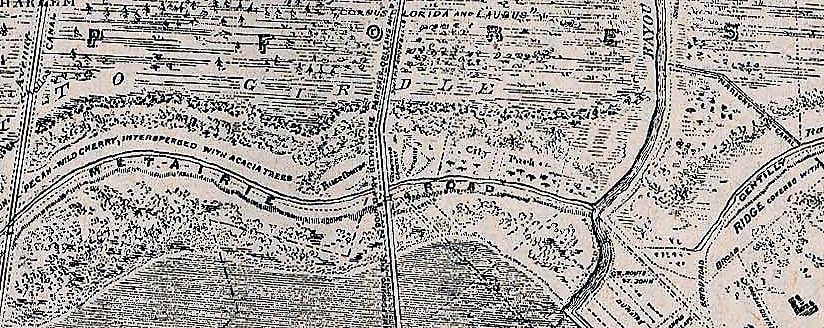

[2] Daily Picayune, April 21, 1846, 2. [3] “Cypress Grove Cemetery,” Daily Picayune, September 15, 1842, 2. Full text: “CYPRESS GROVE CEMETERY. A portion of this rural cemetery having been appropriated for interments in GRAVES, application can be made at the Firemen’s Insurance Office; to M.C. Quirk & Sons, or Mr. Monroe, Undertakers. The Superintendent will also receive at the ground any corpse for interment, on payment of $5 for grown persons and $3 for children. GEORGE BEDFORD, President F.C.A.” [4] “Grand Fancy Dress Ball,” Daily Picayune, February 26, 1852, 3; “Fireman’s Funeral,” Daily Picayune, August 14, 1847, 2. [5] “The City: An Interesting Ceremony,” Daily Picayune, January 3, 1854, 1. [6] Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1855 (New Orleans: Printed at the office of the Picayune, 66 Camp Street, 1855), xiv. [7] Pie Dufour, “Old Cemetery Getting New Look,” Times-Picayune, November 10, 1968. [8] In Cypress Grove, sexton and stonecutter Leonard Gately was instrumental in developing sections into sellable space. Daily Picayune, April 12, 1959, 154. Part One of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. The foot of Canal Street at City Park Avenue is surrounded by cemeteries. At one end, the bronze statue of the Elks Lodge tumulus presides over ever-bustling traffic - right now, in December, the Elk has been decorated with a festive red nose. Facing the intersection from another side is the tall edifice of Odd Fellows Rest. The entrance gate of Cypress Grove stands out even in the grandiose company of these monuments. Comprised of two gatehouses and towering Egyptian Revival pillars, the gate has stood longer than the Elk, the Odd Fellows, or any other cemetery in the area. Within these gates is the oldest rural cemetery in New Orleans. Cypress Grove’s significance is self-evident – its wide avenues showcase example after example of high funeral architecture, of stories that strike the heart of the New Orleans history. But there’s another story among the thousands of tombs in the cemetery. It’s the story of a landscape now obscured by time, of what it used to mean to walk through these aisles. Beyond the mowed grass and paved paths is evidence of what once was a lush, tree-lined landscape on par with the garden cemeteries of the northeast. If you look hard, you can still find it there. The Firemen’s Cemetery Cypress Grove was founded in 1840 by the Firemen’s Charitable Association (FCA), now known as the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association (FCBA). The Association was organized in 1834, about five years after the first New Orleans volunteer fire companies formed. Originally, the Association served in a manner similar to other mutual aid societies: providing social and financial support to the city’s volunteer firemen. Within its first decades, however, the Association became the fire department itself. Until the city switched to a paid fire department in 1892, the Association was responsible for all firefighters in New Orleans – and all firefighters were volunteers.[1] The tale of the founding of Cypress Grove is one well-known to cemetery lovers in New Orleans. On New Year’s Day 1837 while carrying out his duty with Mississippi Fire Company No. 2, thirty-five year-old Irad Ferry perished in a fire on Camp Street. Dubbed the “the first martyr” of the newly-formed fire department, Ferry was venerated with a public funeral and a large memorial march. He was originally laid to rest in Girod Street Cemetery. Along with relief services for their members, benevolent societies of this time provided burial benefits to their members. The Firemen’s Charitable Association was no different, and considered purchasing a section of Girod Street Cemetery for that purpose with plans for Ferry’s monument to be built at its center. But in 1838 the death of Destrehan plantation owner Stephen Henderson widened the Association's prospects. In addition to multiple provisions regarding people enslaved by Henderson, the will specified large bequeaths to religious and social charities, and $500 per annum to the Firemen’s Charitable Association.[2] On Sunday, April 25, 1840, a nearly one thousand firemen, clergy, and prominent citizens marched through downtown New Orleans, each wearing mourning bands and a few carrying urns representing the ashes of their martyred comrades. At Canal Street, they boarded train cars and traveled to Cypress Grove Cemetery, where they re-interred the remains of Irad Ferry beneath a great monument designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and constructed by stonecutter Newton Richards. In a nearby tomb constructed for this purpose, the remains of eleven additional firemen were buried.[3] The Rural Cemetery At its founding in 1840, Cypress Grove became the sixth active cemetery in New Orleans, and the only cemetery at the lake-side foot of Canal Street.[4] Its predecessors were decidedly urban in design: dense, utilitarian though beautiful, and without significant landscaping. A possible exception to this rule was Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, located in what would become the Garden District. Lafayette No. 1 has been referred to as a “transition” cemetery between urban and rural model cemeteries. But even this cemetery was squeezed into a single city block, with no room for the rolling greenery that had become popular in American cemetery design by 1840.[5] Cypress Grove was destined to become something different. Enormous in land area by contemporary New Orleans standards, it was conceived by relative newcomers to the New Orleans Francophile aesthetic. Members of the FCA were often northern-born – for example, Irad Ferry was from Connecticut – and thus influenced by English sensibilities. The Americans brought with them new ideas for cemeteries. They were inspired by what they saw at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and many more. These were cemeteries that were designed instead of planned, with undulating pathways that strolled past weeping willows and reflecting pools. This was the rural cemetery movement, a great shift in the history of cemeteries that would change the American perception of death forever. The rural cemetery movement arose in the northeastern United States as a result of the expansion of cities. Advances in industrialization within the urban landscape created in city-dwellers a longing for the countryside. Furthermore, this same industrialization advanced the American middle class in such a way that recreation was newly defined. Inspired by English landscape design, the rural cemetery was the predecessor to the public park – in fact, Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed one such cemetery in California. This shift in the appearance and purpose of cemeteries coincided with many American cultural movements like Romanticism and the “beautification of death period.” The Firemen’s Charitable Association was certainly aware of this trend. In addition to the explicit use of the term “rural cemetery” in FCA planning documents, the Association expressed a disdain for contrasting urban cemeteries: It would seem almost superfluous to set for the advantages of this rural cemetery. The rapid growth of our city has already encroached upon the tombs of its fathers, and the sacred relics of the dead have been compelled to give way to the cold and selfish policy of speculators, and the intrusion of business; and the solemnity of the grave yard is disturbed by discordant shouts of merriment, and the baleful proximity of the dissolute.[6] If there was any question as to whether the FCA was directly influenced by the rural cemetery movement, one must note that the iconic Cypress Grove entrance gate is a near-exact facsimile of the gate at Mount Auburn. The Cemetery at the Half-Way House For those in FCA who wished Cypress Grove to be a truly rural cemetery, a better location could not have been chosen. The new cemetery was situated at the confluence of vital infrastructure lines: the New Basin Canal and Shell Road, Bayou Metairie, and rail lines at Canal Street. Although the area was an important checkpoint in travel through the area, it was largely undeveloped. One map from 1849 describes the area as a “ridge covered with live oak, persimmon, liriodendron, pecan, wild cherry, interspersed with acacia trees.” The cemetery itself would have, in its own way, water features much like the rural cemeteries it emulated. Early descriptions of the cemetery plan boast “frontage” on both the New Basin Canal and Bayou Metairie. In fact, Cypress Grove Cemetery once straddled Bayou Metairie (today City Park Avenue). The bayou divided Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 1 (present-day Cypress Grove) and Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, a potter’s field now covered by Canal Boulevard. The location of the cemetery not only suited the rural aesthetic but also the new role of the cemetery as a venue for picnics and outings. The Shell Road, which ran alongside the New Basin Canal toward Lake Pontchartrain, was a popular day trip for visitors and locals alike.[7] The Half-Way House and Road House were located at the meeting of the Shell Road and Bayou Metairie – both places of rest, refreshment, and entertainment located at the midway point between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, further cementing Cypress Grove’s destiny as a park-like destination. Growth and Change Those who were drawn to own tombs and lots after 1840 chose Cypress Grove for its bucolic location, wide aisles, and landscaping. In its first twenty years, the cemetery would be filled with some of the grandest architecture New Orleans craftsmen could offer. Its aisles, all named after trees and plants, would bristle with their namesakes shading each pathway. The finest cast iron fences would encircle family tombs clad in marble and Pennsylvania brick. Cypress Grove became, in some ways, an extension of Girod Street Cemetery. Protestants and other non-Catholics sought property within its walls, bringing their taste in obelisks and urns with them. Cypress Grove became home to the second tomb for traditional Chinese burials in New Orleans. The Slark and Letchford families built two tombs inspired by stately Gothic spires along the cemetery’s marble-clad side wall vaults. Cypress Grove would not be alone at the confluence of bayou, canal, and railroad for long. In the same year Cypress Grove was founded, St. Patrick’s Cemetery No. 1 was established. Cypress Grove would be joined by Greenwood Cemetery, Odd Fellows Rest, Dispersed of Judah and other Jewish cemeteries, Charity Hospital Cemetery (now Katrina Memorial), and Masonic Cemetery No. 1. In 1872, Metairie Racetrack would be converted to Metairie Cemetery, and Cypress Grove would be supplanted as the great rural cemetery of New Orleans. One hundred seventy-five years after Cypress Grove’s dedication, there are twelve cemeteries clustered near the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The New Basin Canal was filled in the 1960s and replaced by the Pontchartrain Expressway. Metairie Bayou has been filled and City Park Avenue widened atop it. The Half-Way House and other former New Basin Canal structures were demolished in recent decades. Today, the New Orleans Emergency Communication District buildings are located at the site. Cypress Grove may not be so easily recognized for what it once was. Its trees are mostly missing, replaced by deep ruts in sod where herbicide has taken hold. Many of its great structures have changed or completely disappeared – tumuli stripped of their grassy knolls, wall vaults stripped of their marble facing. Next blog post, we dive deeper into the architectural history of specific tombs and structures in Cypress Grove Cemetery and how they have changed over time. [1] Thomas O’Connor, ed. History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FMBA, 1890), 54-57.