|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC maintains an informal database of cemetery vandalism incidents around the world based on news reports. From online journalistic alerts, each report of a vandalism incident is cataloged for location, motivation (if one is identified), number of markers affected, estimated repair costs (if identified) and other factors. The data below is based on this database, cataloged from January to December 2017. It must be noted that cemetery vandalism is often unreported to local press. Our database cannot include unreported vandalism and does not represent the most comprehensive total of vandalism incidents. Instead, it provides a snapshot of some incidents and issues. In 2017, 105 individual incidents of cemetery vandalism were reported to local press across the United States. While the tally of individual incidents, ranging from New York to Hawaii, Florida to Oregon, is significantly less than those reported in 2016 (184 incidents) the total number of headstones and markers affected increased from 1,811 to 2,353, and estimated repair costs reported by cemetery authorities increased from approximately $488,000 in 2016 to approximately $1,766,000 in 2017. Cemetery vandalism is a much more common occurrence than it is commonly understood to be. Each year, hundreds of cemeteries experience loss and damage resulting from stolen grave goods, toppled stones, and graffitied markers. As we noted in our 2016 post on cemetery vandalism, the motivations for such acts vary widely. In many cases, acts of vandalism can be explained by adolescent antisocial behavior – “kids” knocking over headstones for fun or as an expression of control. But in so many other cases, vandalism has a deeper motivation as an expression of political or racial undercurrents. In 2017, racial, religious, and politically motivated cemetery vandalism was pushed to the forefront of American news coverage. In our recap of 2017 in cemetery vandalism, we review incidents of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents, and the community response that helped cemeteries recover. After August protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, incidents of cemetery vandalism targeting Confederate monuments increased. From this point, we will also discuss cemetery vandalism incidents outside the United States with an eye to similarities of motivation. Yet despite 2017’s increases in cemetery vandalism severity, responses from law enforcement may have increased in efficacy. A number of vandals who perpetrated cemetery crimes in 2016 were identified and apprehended this year, and responses have grown more robust. Anti-Semitic Cemetery Vandalism In February 2017, two Jewish cemetery vandalism incidents became national news. Outside St. Louis, Missouri, approximately 175 headstones at the Chesed Shel Emeth Society Cemetery were toppled. Within a week, 100 headstones at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania were also toppled. Vandalism incidents in which more than one hundred headstones are affected are not entirely unusual. However, the two incidents in Philadelphia and St. Louis occurred concurrently with popular malaise around the specter of anti-Semitism – dozens of false bomb threats were made by phone to Jewish community centers around the country in the previous month. When these two cemeteries were vandalized, national and local response was enormous. While the perpetrators in either incident have yet to be apprehended, and the St. Louis incident was not initially pursued as a hate crime, these two cemeteries became rallying points for resistance to anti-Semitism. The incidents also turned the public eye to the larger issue of cemetery vandalism in such a way that affected future responses to such incidents. Unfortunately, these two large-scale incidents were not the only examples of anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism to occur in the United States in 2017. In January, two young women and a young man (ages 19, 16, and 20 years old, respectively) were arrested for anti-Semitic graffiti at a cemetery in Scottsburg, Indiana. Also in January, anti-Semitic and anti-police graffiti was found at Oak Grove Cemetery in Hyannis, Massachusetts – an incident that was investigated as a hate crime. Additional incidents in Rochester, New York, and Melrose, Massachusetts in March and July (respectively) were so investigated. In May, another cemetery in Philadelphia was the victim of what police investigated as an anti-Semitic hate crime.

In fact, money raised to aid Mount Carmel and Chesed Shel Emeth exceeded their needs. Some money raised in Missouri was sent to other St. Louis-area cemeteries to help improve security. Other excess funds were earmarked for other Jewish cemeteries, including Golden Hill Cemetery in Lakewood, Colorado. The state legislatures of New York and Pennsylvania discussed raising criminal penalties against those convicted of cemetery vandalism. While New York did see a threefold rise in cemetery vandalism claims to their state cemetery preservation fund, the state declined to increase penalties. In July 2017, the state of Pennsylvania did increase penalties, including a $2,000 fine and possible 30 days imprisonment. Other Religious and Culturally Motivated Vandalism In general, religious and culturally-motivated cemetery vandalism increased from 2016 to 2017. While in 2016 a number of African-American cemeteries were targeted for race-based vandalism, such crimes appeared to target other groups in 2017. In August, newly-established Al Maghfirah Cemetery outside Minneapolis, Minnesota was vandalized with swastikas and menacing spray-painted messages. The Federal Bureau of Investigation was notified and began investigation. Also in August, Cypress Hills Cemetery in Glendale, Queens, New York was vandalized by three young men who spray painted anti-Muslim, anti-Asian, and anti-African American graffiti on cemetery walls. In this case, the perpetrators were filmed by surveillance cameras. The three men were arrested in October 2017 and charged with hate crimes. Confederate Monuments After the mass murder of nine worshippers at Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015, national dialogue turned to the removal of Confederate monuments throughout the country. The Confederate monuments in question were, in almost all instances, those set in public space and not in cemeteries. For example, New Orleans city council voted to remove four public Confederate monuments in December 2015, but excluded Confederate monuments in cemeteries from discussion. In 2017, public discourse regarding Confederate monuments in New Orleans did include cemeteries, but only as possible locations that removed monuments could be relocated. In 2016, only one incident of vandalism targeting Confederate monuments took place, in Raleigh, North Carolina. After the shocking protests and violence that took place at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017, targeted cemetery vandalism increased. Five incidents of vandalism of Confederate monuments took place in United States cemeteries after Charlottesville, as well as one additional incident involving a Union soldier monument in California. In Los Angeles, California, a Confederate monument placed in Hollywood Forever Cemetery by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1925 was graffitied with the word “NO” in permanent marker. Shortly afterward, the UDC removed the monument and placed it in storage. Other cemeteries increased surveillance and security after the Charlottesville protests in anticipation of targeted vandalism. Such was the case in Springfield National Cemetery in Missouri. However, during a shift change between security details, red paint was splashed across a monument to a Confederate major general. This incident was tied in newspaper reports to a recent statement by Missouri state legislator Warren Love, who stated that those who vandalize monuments should be “hung high with a rope,” prompting calls for Love’s resignation. Other incidents took place in Fairfax, Virginia, and Columbus, Ohio, where a zinc monument placed in 1902 was pushed from its pedestal and shattered. Its detached head was stolen. At Woodlawn Cemetery in West Palm Beach, Florida, a 1941 Confederate monument was tagged with multiple messages in red spray paint. Most recently, Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Rome, Georgia, was targeted when a granite statue was pushed from its pedestal and repeatedly struck with an unknown instrument. Catching Vandals: “Who Does Something Like This?” In our 2016 vandalism blog post, we noted that is extremely unlikely for cemetery vandals to be identified and apprehended. In 2017, arrest of cemetery vandals was slightly more likely than in the year previous. Most notably, the investigation into 2016 anti-Semitic vandalism of Beth Shalom Cemetery in Warwick, New York, came to a close in October when 18 year-old Eric Carbonaro was arrested for the incident. Carbonaro was charged with a hate crime and tampering with physical evidence, after he deleted photographs of the vandalism from his phone. Carbonaro was found to have conspired to commit the vandalism with two other people, one of whom made a meme of Carbonaro’s face under the caption “Secretly spray paints Jewish cemetery and gets away with it.”

The cemetery owners claimed the $15,000 in damage would be covered by the cemetery itself. Moreover, the cemetery held a cookout for families whose property had been damaged, at which they were given new flowers and flags to place on their lots. In September 2017, more than thirty of a total one hundred monuments were toppled in Bohemian Pecenka Cemetery in Marysville, Kansas. The cemetery was cared for by the local high school 4H, whose members overheard their five teenage classmates admitting to the act and turned them in. In October, a Cordova, Alabama man was arrested for vandalizing Mt. Carmel Cemetery. In an interesting attempt at community policing, the vandal, 23 year-old Joshua Hicks, was brought to the cemetery to meet families whose property he’d damaged. Hicks explanation for why he vandalized the cemetery: “… he likes to get intoxicated, gets bored, and likes to vandalize.” Other arrests for cemetery vandalism in 2017 included the June arrest of an adult man who repeatedly vandalized Historic Japanese Cemetery in Oxnard, California. This man was known to the cemetery and was understood to have mental health concerns. The cemetery declined to pursue charges. A 48 year-old man in Kahoka, Missouri was arrested for removing marble closures from a mausoleum. In Schenectady, New York, a 43 year-old man was arrested for scratching his “rapper’s name” into a headstone at Vale Cemetery. International Cemetery Vandalism Oak and Laurel’s cemetery vandalism database includes all cemetery vandalism-related reports written in English. This usually includes the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, where cemetery vandalism is frequently reported. For example, at Berri Cemetery in Riverland, South Australia, three boys aged 9, 10, and 11 were turned in to the cemetery after their mother found out they had been toppling headstones. As in 2016, vandalism in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland continues to be an issue associated with sectarian conflict. In January 2017, a man in his 50s was arrested for vandalizing the monument of Irish politician Éamon de Valera in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. In addition to criminal charges, he was banned from the cemetery. In the April anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, a remembrance wall at Glasnevin was splashed with paint.

Additional incidents took place in Northern Irish cemeteries, including Belfast City Cemetery and Goldenbridge Cemetery, where the front gate was set on fire. Derry/Londonderry City Cemetery, which was noted in 2016 to have repeated vandalism incidents, did not report any incidents in 2017. In December 2017, two tour guides in Belfast began tours of the city’s cemeteries as a means of combatting vandalism. Other international cemetery vandalism events highlight local and regional political strife. In January, cemeteries in Poland and Ukraine were vandalized with Nazi graffiti and anti-Semitic slurs. Both instances were blamed by local press on Ukrainian nationalists. A Jewish cemetery in Lorraine, France, was vandalized in April in an incident that was seen as anti-Semitic. In Lausanne, Switzerland, the Muslim section of a public cemetery was vandalized with graffiti reading “Muslims out of Switzerland.” Responding to Cemetery Vandalism Cemetery vandalism can be seen as a barometer for political and social unrest. In 2016, we looked at this aspect of cemetery vandalism primarily from an international standpoint – examining vandalism in Ireland and Armenia. In 2017, cemetery vandalism reflected such concerns in the United States more than in the years previous. While this increase in targeted cemetery vandalism is very concerning, it must not be overlooked that heightened attention to cemetery vandalism has had an impact. Recovery from vandalism incidents is slightly more often reported and also includes focus on the communities that use and cherish a cemetery. In 2017, some cemeteries even published press releases asking community members to become involved and vigilant before cemetery vandalism occurs. Criminological theory states that cemeteries which appear cared for and visited tend to experience less vandalism. This understanding appears to have been utilized in vandalism responses in 2017. Closed circuit television, security, and other physical and intangible barriers to antisocial activity have also become more common. Prevention and community involvement are shown time and time again to be the best things to combat cemetery vandalism. Cemetery vandalism is inevitable, but can be mitigated and prevented to an extent. As we move forward into 2018, we hope to see the kind of police follow-through, community response, and enthusiastic recovery that was seen in 2017 despite the discouraging events that precipitated them.

5 Comments

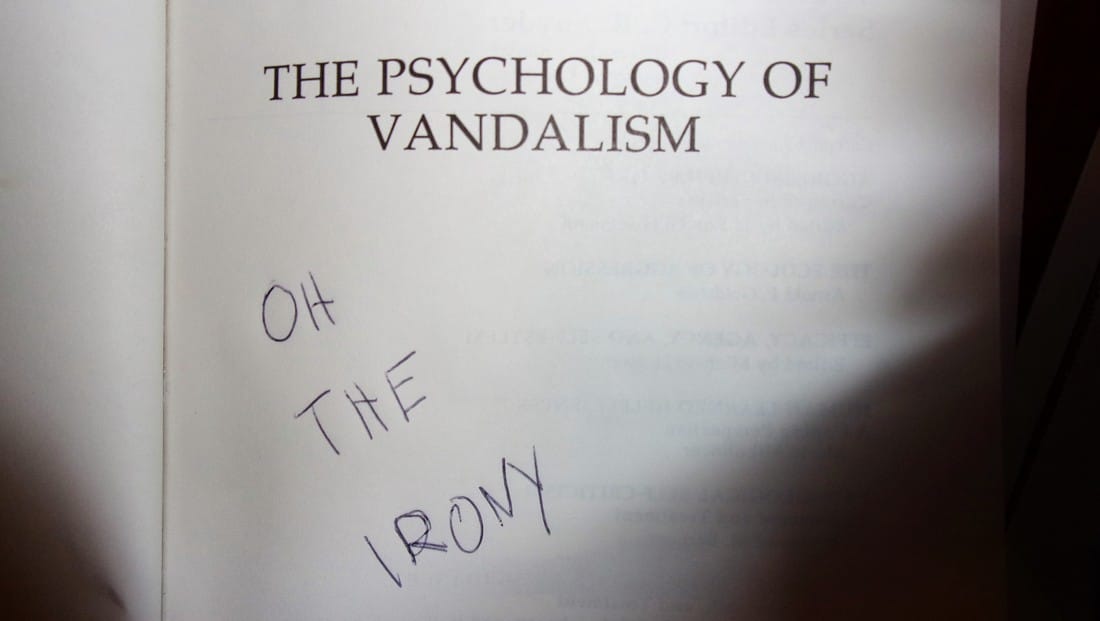

2016 was a momentous year – but in cemeteries worldwide, it was more or less average for incidences of vandalism. Every year, hundreds of cemeteries suffer crimes of toppled stones, graffiti, desecration of remains, and outright demolition. In the United States, this year at least 1,811 individual markers were affected, costing at least $488,000.[1] Cemetery vandalism is not rare or unusual. Its causes vary from adolescent antisocial behavior to politically, racially, or religiously motivated crimes. The only commonality among most instances of cemetery vandalism is the process through which the crime may have been prevented, and how its effects can be mitigated. While Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a New Orleans-based cemetery preservation company, worldwide cemetery vandalism is a special research interest. This blog post is based on an ongoing data collection project based on news reports of cemetery vandalism throughout the year. We catalog each incident, indexing for motivation, type of vandalism (knocked-over headstones, graffiti, theft of grave decorations, etc.), location, and whether an offender is identified and prosecuted. Reports originate primarily in the English-speaking world (United States, Canada, UK, Ireland), but often include English-language reports from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Through compiling the entire year’s reports of cemetery vandalism, it is possible to identify some patterns in criminology, reporting, and recovery. So, prepare to get your headstones toppled, this is 2016 in cemetery vandalism. The Psychology of Vandalism Psychological and sociological theories regarding the motivation of vandalism offenders describe the “typical” vandal as a white male, aged 14 to 20, with a background in petty crime.[2] For these offenders, vandalism can be a means of exerting control on a world in which they feel they have little agency (“equity-control theory”). Other explanations include enjoyment theory, which views vandalism as a source of “flow” for an offender inhabiting an otherwise stifled existence, and aesthetic theory, which simply states that vandals tend to target more complex targets than simple ones.[3] Vandalism in cemeteries tends to add a layer of complexity to psychological theory. The significance of the cemetery in any culture is tangible – the cemetery represents overarching themes of death, remembrance, and identity. When a cemetery is vandalized, it can be perceived as a symbolic attack on death itself, or the entire culture represented by the cemetery. This perception goes both ways – both offenders and victims recognize this meaning. To date, no psychological studies have addressed whether the teenager knocking over markers in his neighborhood cemetery is, on some deep Freudian level, attacking the very concept of death. But perhaps someday such research will be conducted. Politically, Racially, and Religiously Motivated Vandalism The notion that cemeteries represent communities both symbolically and functionally is so often visited that it risks becoming cliché. Yet in no other context is this idea more vital and tragic as in incidents of large-scale vandalism. The cemetery as embodiment of group identity is a global concept. In 2016, international conflicts repeatedly manifested in cemeteries. In Poland, cemeteries of fallen Soviet World War II soldiers were vandalized, representing a clash between historic and contemporary perceptions of the Soviet Union. Baha’i cemeteries in Iran were systemically destroyed. And the ongoing border conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia yielded accusations of cemetery desecration from both sides. Case Study: Derry City Cemetery In Northern Ireland, cemetery vandalism, regardless of motivation, is associated with socio-political sectarianism. Between 2015 and 2016, City Cemetery in Derry/Londonderry was vandalized at least five times, including an arson event. Simultaneously reported as a crime of adolescent perniciousness and motivated by lingering sectarianism, these incidents tie in to the erection of a paramilitary monument in the same cemetery. In nearby Belfast, the vandalism of a Jewish cemetery was viewed as much as an iteration of loyalist/unionist strife as it was an act of anti-Semitism. Derry City Cemetery did not install surveillance cameras until the fifth reported vandalism incident in two years. Presently, the cemetery seeks the draw of tourism as prevention of vandalism, citing the approach taken by Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. While Glasnevin may have mitigated incidents of antisocial behavior in this manner, the comprehensive management of Glasnevin Cemetery only partially relies on tourism. The cemetery clearly benefits from intensive public and private investment. In this light, Derry City Cemetery has more in common with Dublin’s Goldenbridge Cemetery, which was vandalized three times in 2014-2016. In the United States Politically, racially, and religiously-motivated vandalism is no stranger to cemeteries in the United States, either. In 2016, amidst national discussions regarding Confederate monuments in public spaces and in the wake of the murders at the Emanual A.M.E. Church in Charleston, Oakwood Cemetery in Raleigh, North Carolina experienced a large-scale vandalism event. In this case, the “well researched” anti-racist graffiti tagged the graves of Confederate and Lost Cause figures. The Raleigh incident was the only reported instance of anti-Confederate vandalism in cemeteries. However, racially-motivated attacks on African American cemeteries took place more commonly in 2016. In June, the African-American section of Greenwood Union Cemetery in Rye, New York was stripped of its Memorial Day flags. In August, a Wagoner County, Oklahoma cemetery was vandalized with racial slurs. In this case, a passerby noticed the graffiti and covered it with sheets before notifying the police. Many more cemetery vandalism incidents occurred at African American cemeteries but were determined not to be hate crimes. Anti-Semitic Vandalism The perception of the cemetery as manifestation of cultural identity is especially pertinent in the case of Jewish cemeteries. Cemeteries, along with places of worship, are symbolic of the community itself and are targeted by anti-Semitic vandals in a nearly pathological manner. Anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism is something to which New Orleans itself is quite familiar: Hebrew Rest Cemetery in Gentilly and Dispersed of Judah Cemetery on Canal street were vandalized with anti-Semitic and Nazi slurs repeatedly in the 1960s.[4] In 2016, three Jewish cemeteries in the United States were subject to this type of hate crime. Within one week in February, Zion Hill and Dreyfus Lodge Cemeteries were both targeted, resulting in forty total headstones toppled. The Hartford, Connecticut incidents were both investigated by police as hate crimes. Although no report suggests a culprit was identified, Dreyfus Lodge Cemetery restored the damage and held a rededication ceremony after repairs. Beth Shalom Cemetery in Warwick, New York, was attacked with anti-Semitic graffiti in October 2016. The exterior wall of the cemetery was marked with swastikas and “SS” insignia, days before its congregation observed Yom Kippur. The historic and systemic use of cemetery vandalism to intimidate and attack Jewish communities was clearly recognized by members of Temple Beth Shalom. In an interview with local Times Herald-Record, Rabbi Rebecca Shinder stated the vandalism “represents hatred and persecution of the Jewish people throughout the centuries. It’s a symbol of hatred and intimidation.” Days after the incident at Warwick, hundreds of community members arrived at Beth Shalom Cemetery to help remove the graffiti. Incidents of anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism were also reported this year in the United Kingdom and Germany. Many other incidents likely occurred but were not reported, or were not pursued as hate crimes. There is a frequently-used and oft-misattributed quote among cemetery people, to the effect of “Show me a civilization’s cemeteries and I will show you how civilized they actually are.[5]” The quote is usually utilized when discussing the cost of funerals or the frequency of maintenance. But it has an alternate relevance in the sphere of criminology – political vandalism, hate crimes, and other identity-targeted cemetery crime is itself a barometer for larger socio-political trends. Show someone a graffitied 9/11 memorial, a broken police memorial, or a defaced Jewish cemetery, and they will see the evidence of something much larger. Adolescent Vandalism: Joyriding, Robo-tripping, and Satanism Identity-based cemetery vandalism is extremely serious and too often falls between cracks. Yet the vast majority (90%) of the 127 specific vandalism incidents in the United States in 2016 were untargeted incidents involving toppled stones, graffiti, and joyriding. In these untargeted instances, 18% resulted in the arrest or identification of an offender, usually within one week of the incident itself. Identified offenders were typically juveniles – mostly boys but frequently girls. Adults were apprehended for more complex crimes than stone-toppling. In Hickory, North Carolina, a municipal cemetery was collateral damage as a 47 year-old man under the influence of alcohol attempted to evade police by cutting through the graveyard, mowing over 20 headstones in the process before crashing into a veterans’ memorial flagpole. In Douglas, Arizona, a 53 year-old man was caught in the act of stealing more than 70 brass memorial plaques which he intended to sell at a scrapyard.

“Kid”-associated vandalism also seems to bring with it a deliberate “shock” value. In Tennessee and Arizona, cemeteries were tagged with “satanic” graffiti – pentagrams, “666” and other insignia associated with the occult. In the case of San Xavier del Bac Mission cemetery in Arizona, the local Satanic church was contacted for comment and repudiated the act as something unassociated with their group. It should also be noted that this behavior is not restricted to juveniles: a 56 year-old man in Yorkshire, England was arrested in June 2016 for spray painting a cemetery with similar markings.

Some observations of the 184 reports of cemetery vandalism in 2016 offer these suggestive do’s and don’ts: DON’T:

DO:

Preventing and Recovering from Vandalism Most cemeteries, and especially historic ones, are managed by companies or groups with extremely meager funds. Even cemeteries with considerable endowments often operate with high overhead and little left over after basic maintenance costs. Cemetery vandalism is costly to reverse. The cheapest way to recover from cemetery vandalism is to prevent it. If there ever was a “spike” in cemetery vandalism, it happened in the 1960s, coinciding shifts by cemetery authorities to remove full-time staffing from their properties. Full-time staffing permits cemeteries to control the landscape in a way no other management practice can. Secondly, documentation of any cemetery’s current condition is of utmost importance if vandalism is to be identified in the future. Regular photographs of any property (taken either by the property owner or the cemetery authority) are invaluable in controlling vandalism. Maps, measured drawings, and databases are the armor that can protect a cemetery from tens of thousands of dollars in damage. When cemetery vandalism occurs, it must be reported to local law enforcement. Most law enforcement agencies are unaware that cemetery vandalism is an issue. While filing a police report may not produce an arrest, it does produce an important record for the cemetery authority and (where applicable) insurance responses.[6] When the time comes to make repairs, don’t hurry at the expense of quality. Cemetery preservation is a professional discipline populated by experts who have studied methods and materials for years. Sparing expense to make repairs can result in damage that is much more harmful to markers and headstones than the vandalism may have caused in the first place. Proper repairs can facilitate insurance claims, as well. Direct public interest. Take control of the cemetery’s story. Public interest in the preservation of any cemetery is important even before vandalism occurs. After it takes place, enjoining the cooperation of the public can spell the difference between success and failure. It can even prevent vandalism from taking place again. Many cemetery authorities invite volunteers, hold fundraisers, and fun events that introduce the potential vandal to a welcoming, important place. The fifteen year-old that comes to your cemetery movie night might even be the one who stops his friends from tipping a headstone in years to come.[7] Cemetery vandalism is a cultural occurrence which will never be entirely eradicated. But it can be better understood and studied. That way, in 2017, perhaps prevention may be more robust and recovery swifter. [1] Based on 184 news reports from January 2016 to December 2016, only some of which reported the exact number of markers effected and an exact estimation of repair costs. As many instances of cemetery vandalism are never reported, and most costs are not reported, it is reasonable to assume these statistics are much greater.

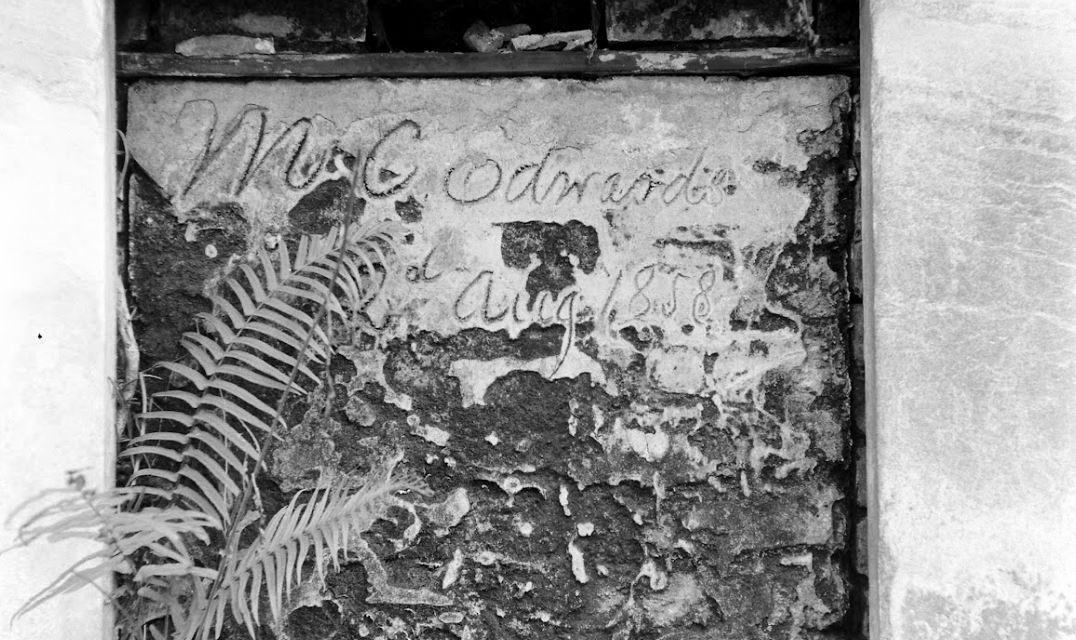

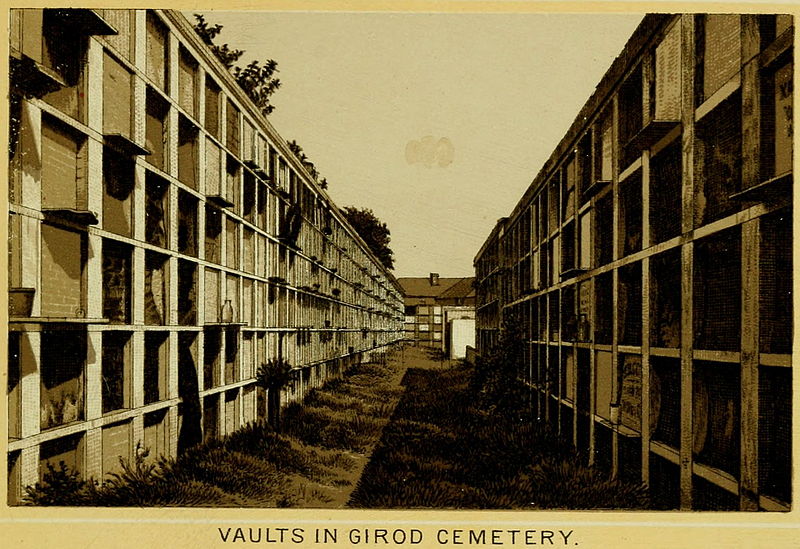

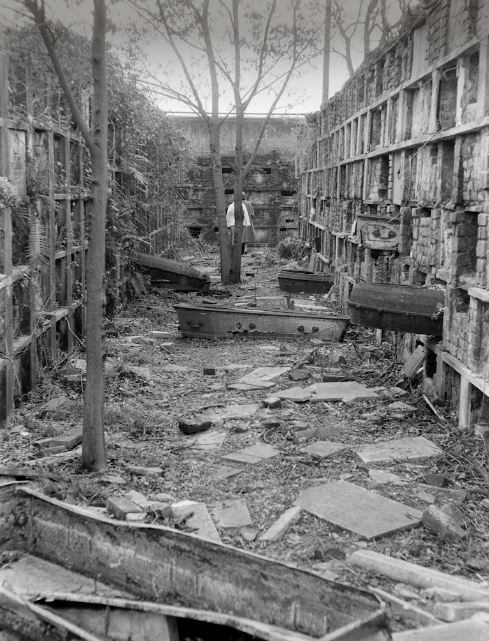

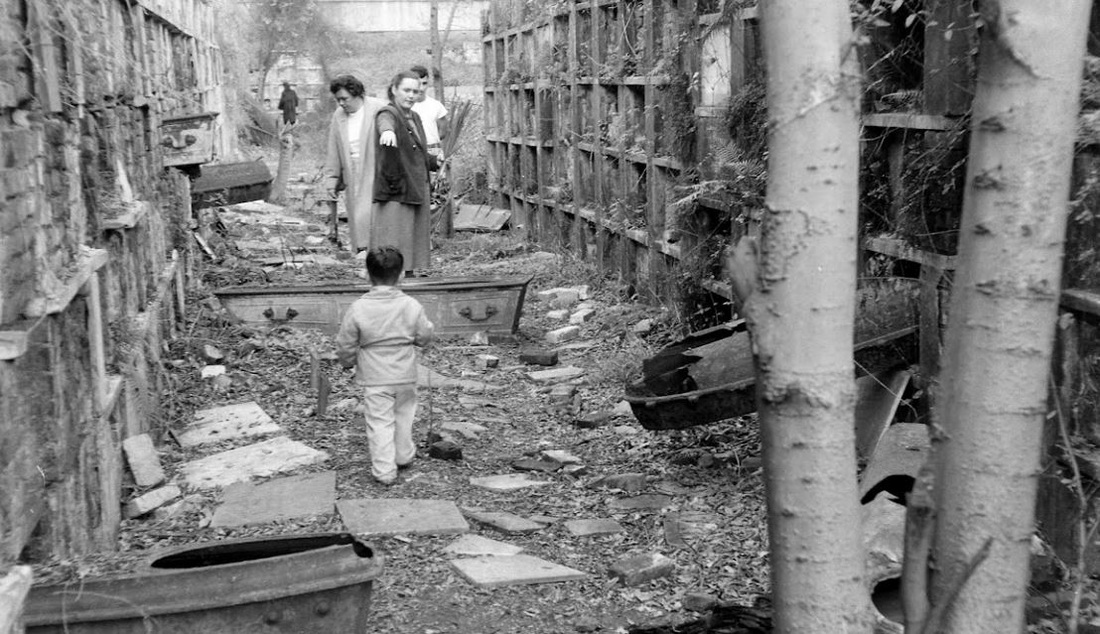

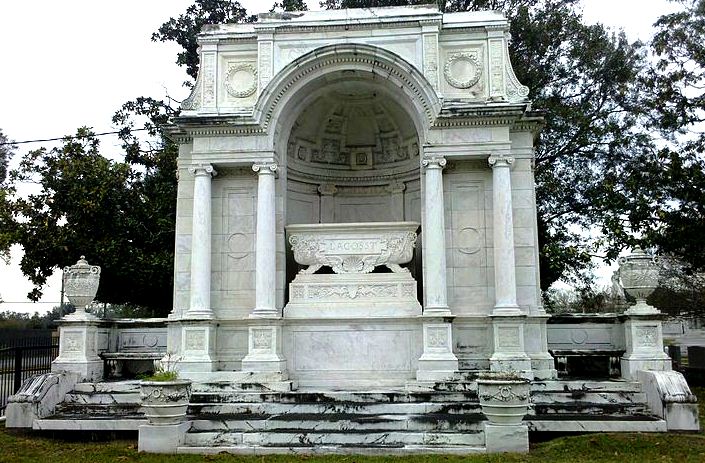

[2] Arnold P. Goldstein, The Psychology of Vandalism (New York: Plenum Press, 1996), 24. [3] Ibid. [4] Emile Lafourcade, “Vandals Strike Jewish Graves: Headstones are Painted with Swastikas,” Times Picayune, July 2, 1967, 1; “Cemetery Vandalism,” Times Picayune, January 21, 1967, 10 (this incident also involved swastikas); “Vandals Paint Gravestones: Hit Dispersed of Judah Cemetery,” Times Picayune, October 27, 1965, 22 (also swastikas). [5] Other variations: “Show me the cemeteries of a country, and I will tell you of its culture, its civilization” (attributed to Tallyrand), “Show me your cemeteries and I will tell you what I think of your people,” (attributed to Benjamin Franklin), and “Show me the manner in which a nation cares for its dead and I will measure with mathematical exactness the tender mercies of its people, their respect for the laws of the land and their loyalty to high ideals” (attributed to Sir William Gladstone). [6] John Eck, “Preventing Theft and Vandalism in Cemeteries,” Annual Conference of the Association for Gravestone Studies, Salem, OR, 2013. [7] Kuri Gill, “Preventing Vandalism,” Annual Conference of the Association for Gravestone Studies, Salem, OR, 2013. This blog post was inspired by the photos within, most of which were taken by Robert W. Kelley of LIFE Magazine in 1957. These images show Girod Street Cemetery in its final moments, as well-dressed adults and children mill around its collapsed tombs and open vaults, with newly-built New Orleans City Hall present in the background of many shots. Mis-labeled “Gerard” Street Cemetery, they offer a vignette of what has long since disappeared from the New Orleans landscape. The full album can be found via Google Cultural Commons here. The topic of Girod Street Cemetery is one that comes up in a few varieties of conversation among New Orleaneans, most often related to the charming notion that the Louisiana Superdome was built atop the burial ground (it wasn’t, per se). The relationship of the old cemetery, known also as the Protestant Cemetery, to the New Orleans Saints football team is one that has been described many times over, best by Richard Campanella and Doc Boudin of Canal Street Chronicles. Check them out to see why you can’t blame the vengeful dead for a losing season. The Protestant Cemetery, 1822 – 1940 The former footprint of the cemetery, however, was indeed quite close to the present-day Superdome. Originally bounded by Liberty, and the former Cypress and Perillat Streets, the cemetery once stood beneath where Superdome parking garages and the Champions Square complex now rise. Founded in 1822, this once-distinctive cemetery lay at the terminus of Girod Street. Previous to that date, non-Catholics were buried in the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. The narrow “Protestants Section” in St. Louis No. 1 was once much longer, but was truncated after construction to Treme Street in 1820. Shortly afterward, Episcopal Christ Church was awarded the land that became Girod Street Cemetery. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Girod Street Cemetery developed into a landscape distinct from its New Orleans cemetery sisters. As the second-oldest cemetery in the city, it amassed the vestiges of early cemetery architecture, from single-vault, stepped-roof structures to more ambitious marble-clad and Classically inspired sarcophagus tombs. The tomb of Angelica Monsanto Dow, who died in 1821, reflected this aesthetic well. Girod Street Cemetery furthermore was an “American” cemetery, in that it became the final resting place for many New Orleans residents who had travelled from elsewhere, particularly the Anglo-American north and Midwest. From these outsiders came tombs and materials inspired by northern cemetery designs – clean, wire-cut Philadelphia brick, liberal use of stone urns and many, many obelisks. Girod Street Cemetery kept within its walls a tableau of cemetery artisanship that stood out from the landscapes of its sister Catholic, municipal, and fraternal cemeteries. Through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, Girod Street Cemetery would become the final resting place for many New Orleaneans of distinction. Heroes of the Mexican American War, civic leaders, and prominent families utilized the burial ground. One estimate suggested that the cemetery was once home to 100 society tombs. For comparison, Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, which is usually noted for its society tombs, has just twenty. In Girod Street Cemetery, the tomb of the New Lusitanos Benevolent Society was likely the most notable. Designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and erected in 1869, the tomb had 100 vaults and a walk-in vestibule framed with a Classical portico. Being somewhat centrally located, Girod Street Cemetery was also heavily utilized as a public burying ground in times of epidemic. It seems as though nearly every major epidemic of the nineteenth century involved a terrible debacle at Girod Street Cemetery, in which bodies were stacked beyond capacity with no one to bury them. This may have also been due to the presence of a de facto Potter’s Field adjoining the cemetery, which was described as early as 1837: “This latter receptacle of the dead [the Protestant cemetery] has for many years been a disgrace to New Orleans. Once the Potters’ Field, it soon became the public burying ground, provided you were able to pay for a vault – otherwise you had to be sent further out into the swamp.”[1] The 1833 cholera epidemic in New Orleans proved especially tragic for Girod Street Cemetery, although it was not necessarily the last time the cemetery fell prey to insufficient manpower in the face of great loss of life: … the unshrouded dead dumped at the gateway of the Girod Street Cemetery accumulated in such numbers that the entrance to its precincts was so obstructed that arriving bodies had to be deposited on the outside; no graves at this time could be dug; no coffins were procurable, for there were neither grave diggers to be had nor undertakers to be found. The City Council was forced to order out the chain gang ‘prisoners’ from the city jails, to dig a trench the whole length of the lower side of the cemetery. It was dug some twelve or fifteen feet wide, and as deep as the filtering water soil would permit, into this receptacle the decomposing bodies were dragged by hooks from the fire companies, without the formality of precedence or order of any kind. As a part of the trench was filled, the earth taken from it was heaped upon the remains of the rich and the poor, the aged and the young.[2] This mass grave would eventually be erroneously referred to as the “yellow fever mound” in later years. In the late 1940s, historians would determine that this feature was in fact the burial of 1833 cholera victims.[3] The Back of the Swamp Girod Street Cemetery, for its stately obelisks and high society residents, would be plagued with issues surrounding its management and topography for most of its existence. In the 1830s, only years into its functional life as a cemetery, it would be noted that its vaults were built with only one brick thickness to their walls, which permitted the “escape of unhealthy odors.”[4] However this was not an issue exclusive to Girod Street – City ordinance did not regulate the quality of tomb construction until the 1850s. What did afflict Girod Street perhaps more than other cemeteries was its location in significantly low-lying land. Girod Street Cemetery swelled with feet of water in Sauve’s Cravasse of 1849, and frequently took on water in other instances, owing to its place on swampy land. In 1880, a special commission of Louisiana state representatives assessed the condition of New Orleans cemeteries and found them all to be in “proper” condition – with the exception of Girod Street Cemetery. Noting, “in the event of rain [Girod Street Cemetery] is always flooded to such an extent that it will affect the sanitary precautions necessary to prevent the contracting or spreading of any diseases,” the commission recommended the cemetery be closed. This recommendation was apparently declined.[5] Girod Street Cemetery’s troubles would not end there. The Fall of Girod Street Cemetery Through the course of its existence, Girod Street Cemetery was owned and operated by Christ Church Cathedral. Until the mid-twentieth century, most religiously-affiliated cemeteries were managed by the respective congregation that owned them. These congregations appointed a sexton or caretaker to manage them by performing burials, building tombs, and keeping records. Although city law required sextons to compile records to be submitted to the Board of Health, the interment records of each cemetery were kept by each sexton to varying degrees of organization. At the turn of the century, increasing industrialization of the monument trade shifted the role of sexton away from groundskeeper and toward that of a sales agent. In some cases, this meant a decline in peripheral duties. This shift is often credited for the lessening of care for the cemetery, as is the inclination of families to move their loved ones remains to newer cemeteries (namely Metairie Cemetery, established 1872). Lack of sellable space and changing racial demographics in the neighborhood of Girod Street Cemetery are also noted as causes for decline. For any combination of these reasons, or others, the administration of Christ Church found themselves in a difficult bind with their cemetery.[6] By the early 1940s, reports on the condition of Girod Street Cemetery appear to have drastically worsened. Wrote one reader in a 1943 letter to the Times-Picayune: … I was horrified to find many of the tombs broken open and others completely destroyed. There was a large fire burning at the top of one of the tombs. I saw what looked like wooden boxes burning. The cemetery looks more like a poultry farm. Atop the tombs are a number of chicken coops, and chickens wandering everywhere, and some of the lovely trees are completely or nearly burned down. Where are the owners of these tombs, that such desecration is allowed? And who cares for this unfortunate burying place?[7]

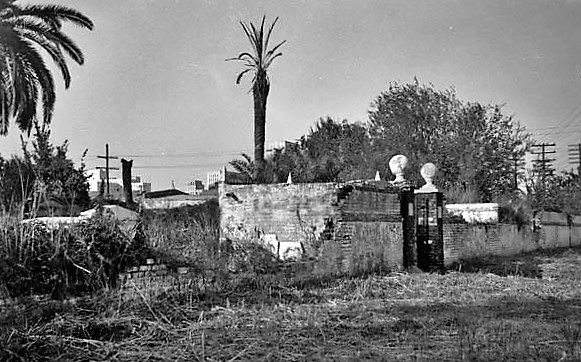

By the time of this announcement in 1947, Girod Street was merely joining in a much larger phenomenon in which cemetery management was drastically changing. In 1945, the City of New Orleans eliminated the position of sexton from the six municipal cemeteries. In the years following, former sextons and stonecutters would go into business for themselves as cemetery owners, profiting primarily from streamlined materials and low overhead costs. This process was best accomplished by Albert Weiblen, who eventually purchased Metairie Cemetery, and the Stewart family, who built Lake Lawn Park in the 1950s. However, this approach relied on the cemetery having lots available for sale. The last sexton of Girod Street Cemetery, Eugene Watson, died in 1950. In 1948, Christ Church ran multiple notices enjoining tomb owners to repair their property. However, as the cemetery owners pushed to bring the burial ground into the twentieth century, they would stumble over technicalities of property ownership, prohibitive costs, and a booming, modernizing world slowly encroaching on the Girod Street walls. “An Eyesore in the Midst of Progress” The Post-World War II era brought huge changes to nearly every facet of American life. In the cemeteries, everything from materials to business models to the funeral industry transformed. In the American city, revolutionary ideas of urban renewal swept through downtowns, destroying historic districts and erecting aggressively modern new landscapes. In New Orleans this urban renewal took place with mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison, and it took place along Loyola Avenue, where historic buildings were swept away for a new library, city hall, and train depot. The intersection of Liberty and Girod Street, at the boundary of the cemetery, was awkward and could not adequately accommodate recently increased truck traffic volumes. By the late 1940s, even the federal government eyed the Girod Street property as a potential site for a new post office and federal building. In the light of rapidly encroaching superhighways and new urban landscapes, Girod Street Cemetery became even more anachronistic. Perceived as an affront to the bright future of the city’s civic heart, plans to renovate the cemetery fizzled into outright demolition by neglect, aided by the agenda of modern city leaders. Lack of care led to vandalism, which led to inevitable decries that the cemetery was too broken to be fixed. In June 1948, city workers arrived at Girod Street Cemetery and knocked enormous holes in the perimeter wall, hauling away five truckloads of bricks. After protests from Christ Church, Mayor Morrison simply responded that he didn’t realize there would be an objection.[12] In 1954, the City of New Orleans successfully expropriated more than twenty thousand square feet of the cemetery for the purposes of widening Liberty Street. In addition to this seizure of land, city council furthermore requested the mass removal of all remains from the cemetery entirely, and that they be removed to newly-finished Lake Lawn Park, a for-profit venture of the Stewart family.[13] Girod Cemetery is Calling Days after the announcement of the expropriation, city attorneys placed ads in newspaper enjoining any person with family buried in Girod Street to contact the City. Attempt to salvage burials, tombs, sculpture, and any other remaining resource of the cemetery were launched. Many of these reburials had already taken place in years previous by families who suspected the cemetery’s demise. In 1955, the remains, tomb, and monument of Lt. Col. William Wallace Smith Bliss was removed to namesake Fort Bliss in Texas. The Louisiana Landmarks Society led this effort, as it did other efforts to locate families associated with the cemetery. In June of 1955, the city officially purchased the cemetery. In January 1957, it was deconsecrated. Only months later, Louisiana Landmarks member and remarkable cemetery historian Leonard Victor Huber decried the demolition process at the cemetery: “Another 60 days and there will be nothing left of Girod Street cemetery but a memory. Tombs are being broken up… I was in a garden recently with its walls built of marble slabs from the cemetery.[14]” Through the course of demolition, remains of white descent were reinterred at Hope Mausoleum, owned by Leonard V. Huber. African American burials were removed to Providence Memorial Park. In October 1958, Christ Church sold 96,000 remaining square feet of the cemetery to the federal government for nearly $300,000. This sale would transform sections of the cemetery into a parking garage for a planned post office and federal building on Loyola Avenue. Said Frank Schneider of the Times-Picayune, “Girod became an eye sore in the midst of progress but now it will contribute something to New Orleans’ changing skyline. The 14-level post office structure will be the largest federal building in the Deep South.”[15] Learning from Girod Street Although certainly accelerated by ambitions of new urbanism, the issues that led to the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery are the same issues that regularly appear in discussions of historic cemetery management today. The power of the cemetery authority to manage abandoned tombs and lots is a topic of constant contention. Cemetery owning bodies today can write off issues of abandonment by appealing to private property rights, and nearly in the same breath demolish lots that become hazardous or inconvenient to redevelopment. The ability to be conveniently selective regarding Louisiana cemetery law has, in many cases, enabled neglect. This neglect, of course, contributes to cyclical issues of cemetery vandalism, which often goes unabated until conditions are perceived as unsalvageable. The sweeping demolitions that took place across the United States during the 1940s through the 1960s spawned a revitalization of the American historic preservation movement. Iconized by the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in New York in 1963, fatigue over the loss of entire historic districts led to the passing of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 which, among other things, would have likely prevented the Federal government from purchasing portions of Girod Street Cemetery. The tale of Girod Street Cemetery is comprised of much more than a haunted sports arena. For cemetery preservationists in New Orleans, it is a cautionary tale that should never be too far from one’s mind. The stunted successes and disappointing failures could easily revisit any of our burial grounds. [1] “New Orleans Grave Yards,” The Picayune, September 19, 1837, 2.

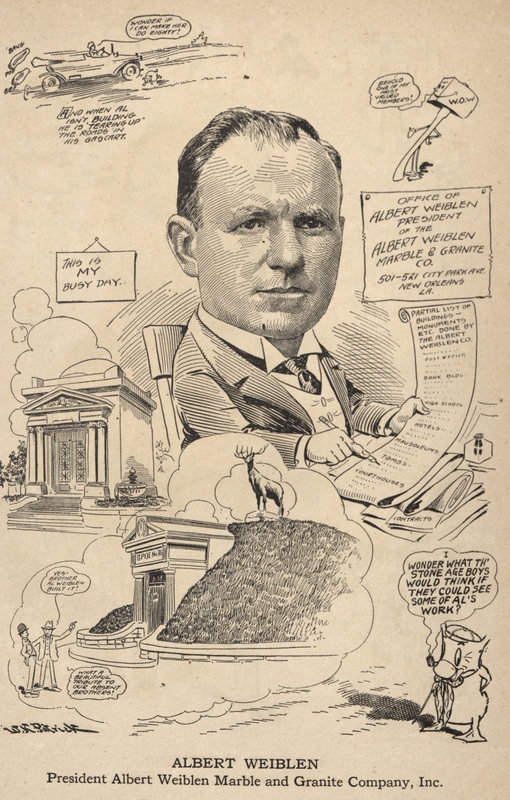

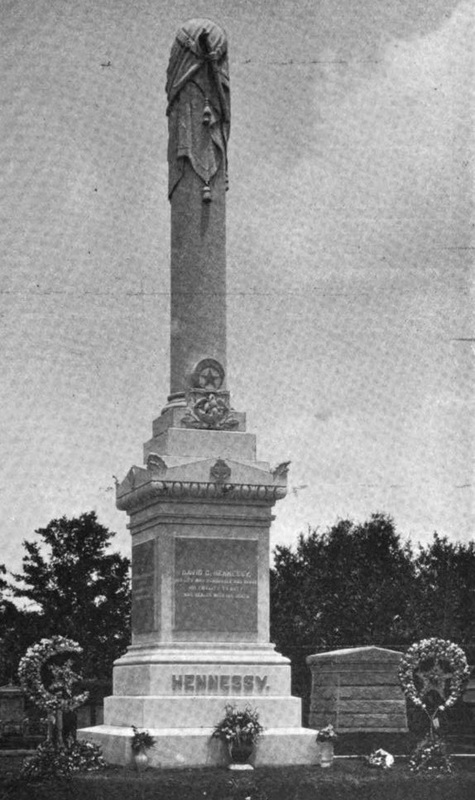

[2] Daily Picayune, August 21, 1885, 2. [3] Leonard Victor Huber and Guy F. Bernard, To Glorious Immortality: The Rise and Fall of Girod Street Cemetery, New Orleans’ First Protestant Cemetery, 1822-1957 (New Orleans: Ablen Books, 1961). [4] “New Orleans Grave Yards,” The Picayune, September 19, 1837, 2. [5] Louisiana State House of Representatives, Official Journal of the Proceedings of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana (New Orleans: The New Orleans Democrat Office, 1880), 285. [6] “The Crumbling World of Girod Cemetery,” Dixie: Times-Picayune States Roto Magazine, August 29, 1954, 6-7. [7] “Historic Cemetery Neglected,” Times-Picayune, June 23, 1945, 10. [8] “Old Cemetery to be Rebuilt,” Times-Picayune, December 21, 1947, 3. [9] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs, Fate of Old Cemetery to Rest with Lot Owners,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945; “Girod Cemetery Inspection Made,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945. [10] “Zulu Chief’s Wish to be Buried with Pomp and Ceremony Fulfilled,” Times-Picayune, August 23, 1948, 24. [11] “Old Cemetery to be Rebuilt,” Times-Picayune, December 21, 1947, 3. [12] “The Crumbling World of Girod Cemetery,” Dixie: Times-Picayune States Roto Magazine, August 29, 1954, 6-7. [13] “Girod Cemetery Strip is Sought,” Times-Picayune, November 12, 1954, 1. [14] “Up and Down the Street: Book on Girod Cemetery Needs Help,” Times-Picayune, August 15, 1957, 19. [15] “Old Burial Spot is Sold as Site for U.S. Garage,” Times Picayune, October 4, 1958, 11. On May 1, 1957, and only a few months shy of his 100th birthday, Albert Weiblen passed away in New Orleans. In his lifetime, Albert Weiblen was a revolutionary figure in New Orleans cemetery architecture. Under his carving hand, the craft of tomb building would expand from a hyper-local, individual cottage profession into a modern industry – spanning the eastern United States and powerfully altering the landscape of New Orleans cemeteries. A German Immigrant in New Orleans Albert Weiblen was born in 1857 in Metzingen, Wurttemberg, Germany. Sources suggest that he began his work as a sculptor in his homeland, apprenticing in the manner that was traditional for the time.[1] Weiblen immigrated to the United States in 1883 and soon afterward began work with local marble company Kursheedt and Bienvenu. Operational from 1867 to 1901, the company was co-owned by Edwin I. Kursheedt, a prolific stonecutter in his own right who, in addition to work in New Orleans’ Jewish cemeteries and other cemetery stonework, supplied the stone for the reconstruction of the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the late 1880s.[2] At this time, New Orleans’ cemetery stonecutting industry was already changing. The florid, individualized Classical-revival tombs popular from the 1840s through the 1860s had given way not only to new styles inspired by Gothic and Italianate revival aesthetics, but also to economies of scale. The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878 galvanized this trend. In this year, the construction of tombs shifted more to “cookie cutter” and slightly simplified styles, replicated by numerous carvers and builders.[3] Weiblen stepped into the cemetery craft scene in New Orleans at a time when this streamlining of tomb construction was in its infancy. New industrial technology, such as saws and machinery to cut granite and marble, new types of stronger hydraulic cements, and stonecutting technology powered by pneumatic chisels and even sandblasting, had been adopted elsewhere in the country, but were a long way off from making their debut in New Orleans cemeteries.[4] When these new tools and methods did arrive, though, it was often Weiblen who spearheaded their use. In 1887, Weiblen left Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s and started his own marble and granite company.[5] His first office and show room was located at 233 Baronne Street, a location he expanded by 1893.[6] Weiblen’s big break came in 1891 when his company won the contract to construct the memorial obelisk to New Orleans Superintendent of Police David Hennessy. Hennessy was murdered on October 15, 1890, an event which sparked riots in New Orleans and led to the lynching of eleven Italian-Americans. The contest had been open to many New Orleans monument men, including Charles A. Orleans, the city’s prominent monument builder at the time.[7] The monument was described by national trade periodical Stone magazine as “one of the handsomest monuments in New Orleans”:

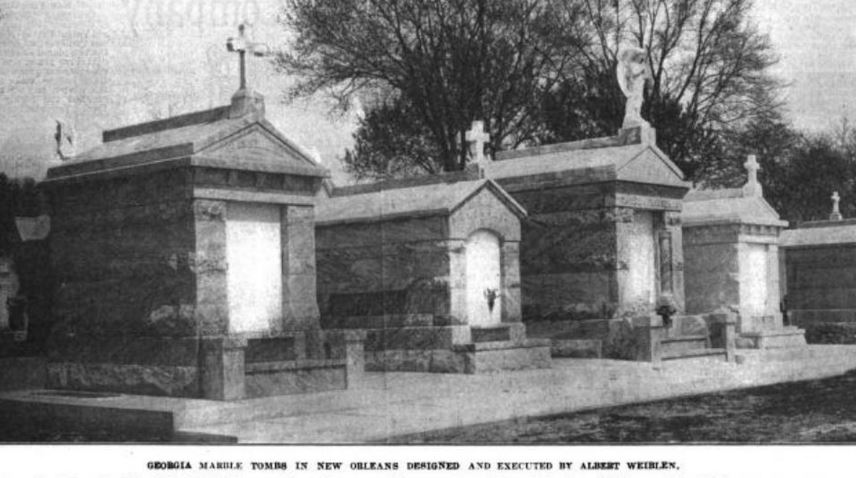

From this location, Weiblen had a workshop complete with powerful equipment to cut, shape, polish, and engrave marble and granite slabs. At the turn of the century, Weiblen’s equipment was not only state of the art (the largest in the South), but was also one-of-a-kind in New Orleans, where technologies were relatively slow to catch on.[10] A skilled marketer and self-advertiser, Weiblen described this equipment in detail in his advertisements, spending nearly half of one circa 1900 advertising booklet explaining its advantages over “the old-time and very laborious manner of cutting by hand.”[11] That Weiblen frequently looked outside of New Orleans for materials and technologies made him, in general, a man of his time. By 1900, the monument industry in the United States was galvanizing as a national trade. Periodicals and trade magazines illustrating the newest and best quarries, saws, cutting methods, and others flourished. Even in New Orleans, Charles Orleans and others had begun to reach outward to peers in the east, newly accessible by infrastructure. Yet Weiblen certainly had a flare for this type of resourcefulness. In 1905, he recruited stonecutters directly from Barre, Vermont, for his shop in New Orleans.[12] The stonecutting shop on City Park Avenue holds in itself a history as visible as any of Weiblen’s tombs. Expanded into the company’s primary sales office in 1907, by the 1920s Weiblen came into possession of five marble sculptures that were once part of the old New Orleans Cotton Exchange. Two of these sculptures, caryatids from the Exchange entranceway, were incorporated into the showroom entrance. The other three, representing Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture, were scrapped for their marble, fell victim to vandalism, or were used as road fill, respectively. The caryatids, however, remain in the Weiblen building, which now houses the Orleans Parish Communication District.[13] The Quarry Man In 1911, Albert Weiblen and his son George leased an interest in a quarry at Stone Mountain, Georgia, from the Venable Brothers company. This was one of a number of savvy moves by the elder Weiblen that helped him cut down his supply chain. By the 1930s, Weiblen would lease another quarry in Elberton, Georgia. His sons, George, Frederick, and John, would all live at the Georgia quarries.[14] In the 1920s, the Weiblens – specifically George and Frederick (who died in 1927) – would begin a long journey of involvement in the carving of the Confederate monument at Stone Mountain, which would not be completed until 1970, the year of George’s death. At these quarries, Weiblen further expanded his infrastructural advantage. By 1936, Weiblen had constructed a full-service carving shop on-site at his Elberton quarry – complete with one of the largest air compressors in the country.[15] Paired with the rail spur he had also built, this permitted Weiblen Marble and Granite to streamline its orders directly from the source. In 1940, Weiblen moved all of his manufacturing operations to Elberton. From this point on, tombs, monuments, and other orders would be ordered from catalogs by customers in New Orleans, manufactured in Elberton, and sent direct by rail to Louisiana, ready for assembly.[16] This advantage also allowed Weiblen to flood the New Orleans market with the products of his quarries, directly transported by rail from their source. Between 1900 and 1940, Weiblen's activities bolstered a stylistic and material shift in New Orleans cemetery architecture. Granite was much more accessible than in the past, and led to new uses as facing and coping material. Georgia marble overtook other sources for new closure tablets, copings, tomb claddings, and other elements. Ever on the marketing edge, Weiblen Marble and Granite even coined a new name for a specific type of Georgia marble, distinguished by sweeping gray and white color patterns: Georgia “Creole” marble (now called “solar gray”). Other burgeoning New Orleans suppliers took up the source, leading Creole marble to be found in large sections of cemeteries like Greenwood, Masonic, and Metairie. Weiblen also attached his name to the granite his company supplied, which is known even today in some circles as “Weiblen gray.” A Cemetery Family Weiblen’s success was passed on to his surviving sons, George and John. George Weiblen operated the Stone Mountain and Elberton interests until his death in 1970. John Weiblen, alternately, assumed his father’s mantle as president of Weiblen Marble and Granite, after Albert Weiblen’s retirement. It was at this time, between 1948 and 1951, that the family company assumed controlling interest in Metairie Cemetery Association. While the purchase of arguably the most prestigious cemetery in New Orleans would have been a grand accomplishment, it also coincided with a larger trend among New Orleans stonecutters in the 1940s.[17] With the monument industry widening to a national scale, and paired with other factors surrounding cemetery management and use, the traditional model of the New Orleans stonecutter that once suited in the nineteenth century was no longer adequate after World War II. This trend was present across all New Orleans cemeteries. In Protestant Girod Street Cemetery, the position of sexton (caretaker), historically held by a stonecutter, was eliminated. This was true also of City-owned cemeteries like Lafayette, Carrollton, Holt, and Valence, in which the position of sexton was eliminated and the management of cemeteries delegated to the City Department of Property Management. The role of the stonecutter, then, was no longer supported by specific cemeteries.[18] Across New Orleans, it became more economically feasible for stonecutters and monument men to shift paradigms from being caretakers of cemeteries to owning the cemeteries outright. Sextons of the Lafayette Cemeteries for three generations, the Alfortish family moved to Gretna and opened Westlawn Cemetery. Victor Huber, monument dealer and caretaker of St. John Cemetery, assumed controlling interest of that burial ground and opened Hope Mausoleum. In 1951, the Stewart family purchased property adjoining Metairie Cemetery and opened Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum.[19] In this sense, Weiblen’s shift from producer of Metairie’s monuments to owner of Metairie’s business was a natural one. John Weiblen preceded his father in death in 1956, leaving his widow, Norma Merritt Weiblen, to manage Metairie Cemetery, which she did so until the property was purchased by Stewart Enterprises, Inc., in 1968.[20] Passing the Torch According to son George, on the morning of May 1, 1957, Albert Weiblen “said he wanted to lie down before breakfast… took one deep breath and he was gone.” At the age of 99 years, Albert Weiblen died, leaving a legacy of innumerable monuments, buildings, statutes, and sculptures behind him. Still working on the Stone Mountain sculpture in the 1960s, George Weiblen noted that he wanted to find a way to carve his father’s name into the stone, “I don’t know how I will work his name in, but there is a way.” Long after Weiblen’s death, the cemeteries of New Orleans bear the mark of his work at nearly every turn. One estimate suggests that nearly half the tombs and monuments in Metairie Cemetery were constructed by Weiblen’s company.[21] In fact, a street off of Canal Boulevard near Greenwood Cemetery is even named after the great monument man. Albert Weiblen was buried in Metairie Cemetery, under a red granite monument. Weiblen's monuments, tombs, buildings, and other projects are innumerable. Weiblen even designed and built the Cuban capitol at Havana. The collection of images below is only a small example of the work of his lifetime.

[1] Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, and Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 55, 62; “Time Marches On, but Weiblen Memorials Remain to Remind,” Times-Picayune, January 25, 1937, 170.

[2] Emily Ford, The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana (MS Thesis, Clemson University, 2013), http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/, 96. [3] Ibid. 121-132. [4] Ibid. 164-181. [5] “Time Marches On, but Weiblen Memorials Remain to Remind,” Times-Picayune, January 25, 1937, 170; Soards’ New Orleans Directories, 1885-1910, these directories discourage the notion that Weiblen actually purchased Kursheedt & Bienvenu, which continued until 1901. [6] “Albert Weiblen Marble and Granite Co., Inc.” Times-Picayune, January 25, 1937, 170. [7] Huber et. al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 61-62. [8] “The Hennessy Monument,” Stone – An Illustrated Magazine, Vol. V (June-November 1892), 142. [9] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8; “A Big New Orleans Plant,” Rock Products, Vol. VII, No. 7 (January 1908), 23. [10] “A Prominent Southern Establishment,” The Reporter, Vol. 32 (August 1899), 7. [11] c. 1900 advertising pamphlet, Weiblen Marble and Granite Company, from Tulane University Southeastern Architectural Archive, Collection 39. [12] “Wanted,” Barre Daily Times, July 26-30, 1905, 7. [13] “More about the caryatids,” Times-Picayune, November 17, 1987, 12. [14] “Fred. E. Weiblen Succumbs Here: Was Executor of Granite Work on Confederate Monument,” Times-Picayune, April 12, 1927, 3. [15] 1936 advertising brochure, Tulane University Southeastern Architectural Archive, Collection 36. [16] 1946 advertising brochure, Tulane University Southeastern Architectural Archive, Collection 36; “Marble Works as New Policy,” Times-Picayune, October 2, 1940, 11. [17] “Stone Company Executive Dies,” Times-Picayune, March 23, 1956, 5; Huber, et. al., 59. [18] “Girod Cemetery Vandals Hunted,” Times-Picayune, June 7, 1952, 3; “A Strong Fund,” Times-Picayune, August 23, 1942, 10; Ford, 116. [19] “Lake Lawn Park Plans Revealed: One of Largest Mausoleums in US Promised,” Times-Picatune, March 8, 1950, 42. [20] “He brings city of dead to life,” Times-Picayune, April 14, 1985, B-8. [21] Huber, et. al., 55. Earlier this month, the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority of Seattle, Washington, announced the planned removal of an estimated one million pieces of chewing gum from the “gum wall” at Pike Place. Located within one of Seattle’s primary tourist destinations, the wall has become tourist destination in and of itself. In 2009, it was declared the second “germiest” tourist destination in the world – just behind the Blarney Stone.

Prior to 1999, it would have been difficult for a casual tourist to know that part of the “Pike Place experience” was to stick used chewing gum on a wall. To be sure, some visitors accompanied by tour guides may have been regaled with stories of this unusual tradition. But without a tour guide the wall would nary have been touched with tourist gum. Guide books did not even include the gum wall until after 2008 – we checked. Alone, the gum wall doesn’t really illustrate much other than a gross and “quirky” tourist tradition. But seen through a lens of lipstick, locks, and tourism, it illustrates an issue all cities seeking to woo tourism dollars should take into account.

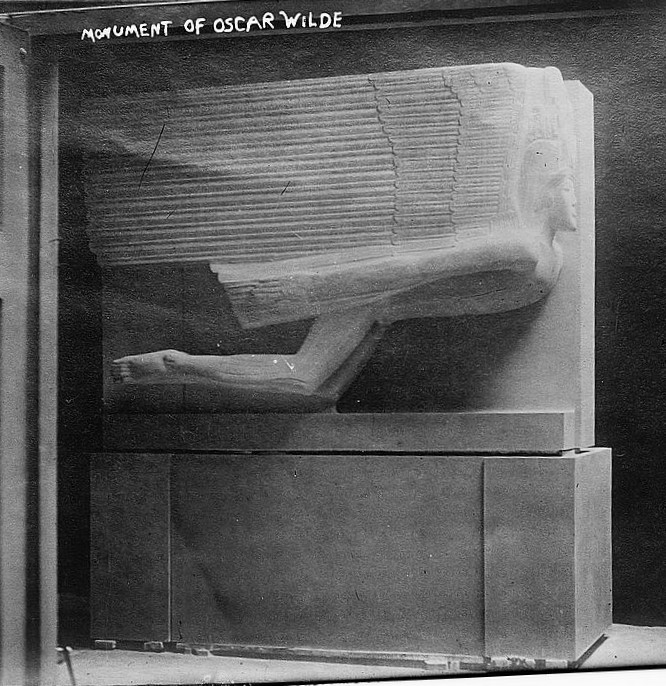

Installed in 1914, the sculpture (by Jacob Epstein, entitled The Sphinx) depicts an angel with male anatomy, which has been the target of mischief for nearly a century. Yet the worst threat to the sculpture arose much more recently. In the 1990s, it is reported, one lipstick kiss was placed upon the limestone marker. In the next twenty years, the load of lipstick marks on limestone became overwhelming, threatening to compromise the piece irreversibly. In 2013, this monument was the third-ranked germiest tourist attraction in the world. Thanks to efforts from the French and Irish governments amounting to more than €50,000, the statue was restored. A plexiglass barrier was installed around the burial place. At present, the plexiglass is inundated regularly with lipstick marks. For New Orleaneans, a lot of these seemingly unrelated local peccadilloes should sound very familiar. Each is a small act executed by tourists involving an easy-to-come-by medium: gum, locks, or lipstick. Many of these things travelers already have in their possession. They each have a somewhat weak background story connecting the tradition to the lure or the romance of the place. They each involve a literal way for an individual to “make a mark” on a place visited - to take part in something larger than themselves. They each began or expanded drastically after the late 1990s. Each of these traditions is innately destructive to historic and cultural resources. However romantic, fun, and exciting these traditions are, they amount to little more than participatory vandalism. All of these traditions have become part of travel-blog echo chambers which have fed the impression that the “tradition” is real and encouraged vandalism far beyond the useful life of click-bait entertainment. We would link to the hundreds of examples of “10 landmarks you must deface while in Paris,” but we work hard not to encourage that type of behavior. For sixty years, New Orleans had its own invented tourist tradition with which to contend. Beginning with a tourist brochure in the mid-1940s, the presumed tomb of voodoo icon Marie Laveau was repeatedly marked in accordance with a contrived wish-making ritual. The majority of these marks were created with similar items to those found in Père Lachaise – lipstick and pens. Although a constant presence in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 for decades, photographic documentation shows that the frequency of vandalism on the tomb increased after the late 1990s. Like Paris and Seattle, this phenomenon is likely related to the widened availability of “off the beaten path” tourism guides and social media resources online. While invented traditions are nothing new, the population of visitors who are likely to participate in them has grown enough that their impact is becoming increasingly difficult to manage. In 2014, New Orleans joined its Parisian counterparts in combating harmful participatory vandalism. The paired efforts of removing vandalism from cemetery property and restricting access to St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 resulted in a measurable decrease in tourist impact. Like Paris, interventions are often costly and can compromise historic resources with the introduction of protective materials (for example, plexiglass is not historic). Intervention can also require an immense investment of resources which may be needed elsewhere. In the moment, it is easy to perceive each incident of tourist “tradition” impact as isolated. Yet the recurrence of this phenomenon in tourism-driven economies proves they do not occur in a vacuum. Little research has been conducted that compares the similarities of such incidents from city to city, or the efficacy of treatment and prevention approaches. New Orleans is unique in so many ways, yet it faces the same difficulties of impact-management and preservation as any other tourism-based economy. It is time to closely examine the impact of perceived “traditions” and other behavioral cues on the preservation of our historic resources. Otherwise, it will not be long before one lipstick kiss snowballs into another expensive debacle. For other great insights on participatory vandalism and invented traditions:

NO LOVE LOCKS™ “No Love Lost on Love Locks,” Laura O’Brien “The Tipping Point Between Vandalism and Art,” Johana Desta, Mashable.com |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly