|

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. Beyond sweeping landscapes and imposing architecture – within the “stories in stone” that are so beloved in New Orleans cemeteries, are the stones themselves. Much like the long-dead people they memorialize, these slabs of honed and carved limestone, marble, and granite journeyed great distances to become part of an irreplaceable cemetery landscape. Whose hands drew that stone from its quarry? Why is the marble found in Greenwood Cemetery drastically different from what we find in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2? Today we share the stories of quarries, infrastructures, and materials that make up New Orleans cemetery stonework. Louisiana Lacks Workable Native Stone The geology of southern Louisiana is similar to that of other states along the Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of mostly sedimentary rock, clay, limestone, and sandstone, Louisiana has few stone resources that would be desirable for cemetery monuments.[1] Furthermore, the stone that is quarried in Louisiana has historically been of poor quality for building. For example, during the 1850s construction of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., requests were made that each state donate a block of native stone to be placed in the interior of the monument. Louisiana sent a block of sandstone that, within the decade, was so crumbling and decayed that it was replaced with a block of Pennsylvania marble.[2] Thus, from the eighteenth century onward, the stone used in New Orleans cemeteries was imported from elsewhere. Various types of slate, marble, and granite were made available as trade routes and quarries opened. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans merchants and dealers offered stone from a number of different places. As time went on, the availability and sources of stone widened.

Arkansas slate was quarried from areas near the towns of Hot Springs, Little Rock, Benton, Malvern, or Mena. This small vein of quality slate, approximately 100 miles long, could produce stone of red, gray, green, or black appearance. Despite the availability of slate from Arkansas, Pennsylvania slate continued to be quarried and shipped to New Orleans. Historic Louisiana newspapers frequently mention the quality and availability of slate from the Bangor quarry in Northampton County. Given the same name as a slate quarry in Wales, the “Old Bangor” quarry had an office in New Orleans by the 1870s. Old Bangor slate is “very dark gray, and to the unaided eye has a fine texture and fine cleavage surface, almost without any luster. The sawn edge shows pyrite.” The Williamstown, Franklin, and Pen Arygl quarries of Pennsylvania also had retail agents in New Orleans, who advertised their slate to be of the same quality as that of Wales.[6]

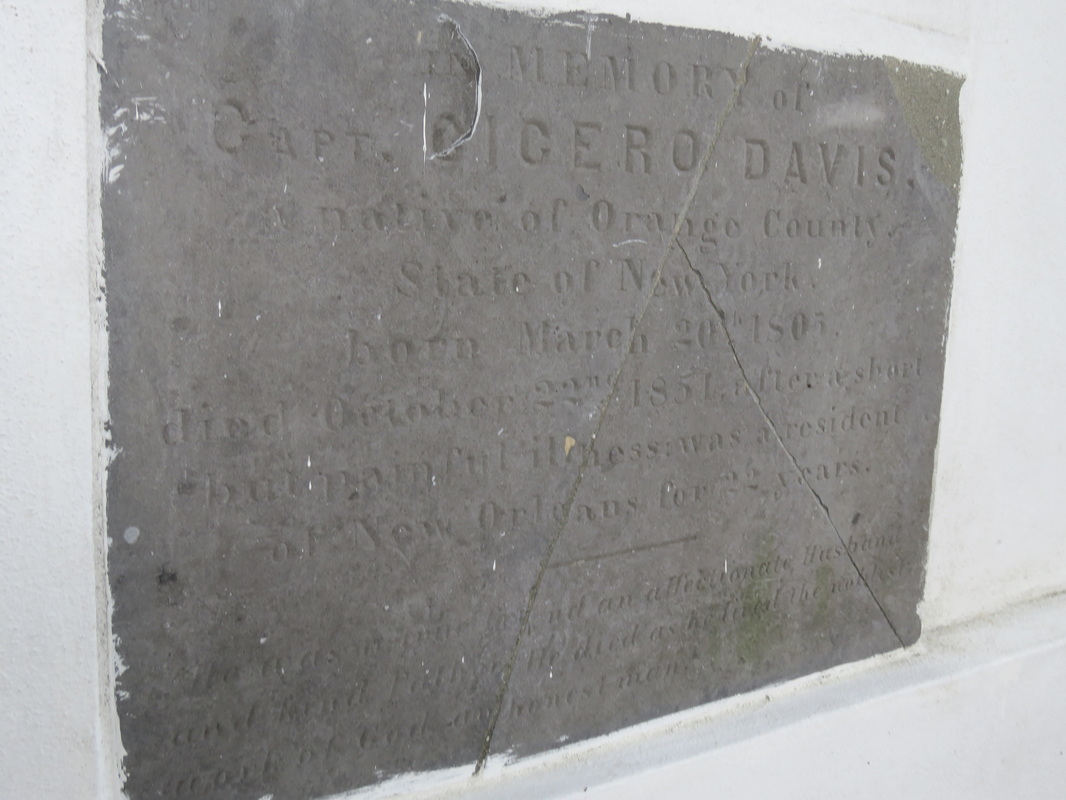

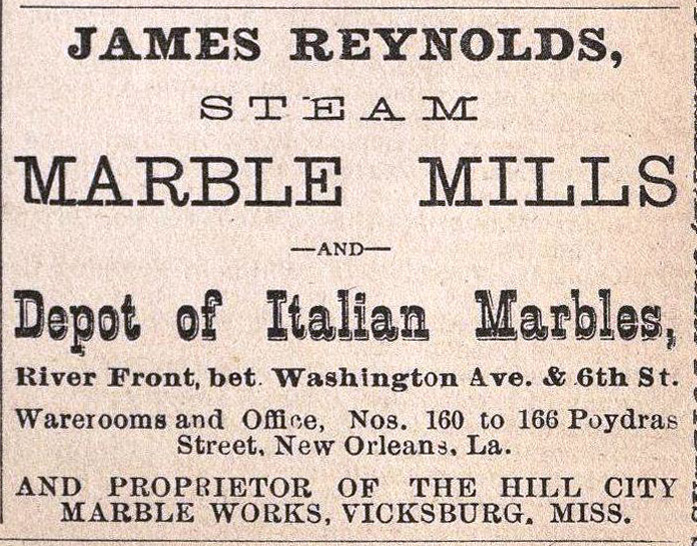

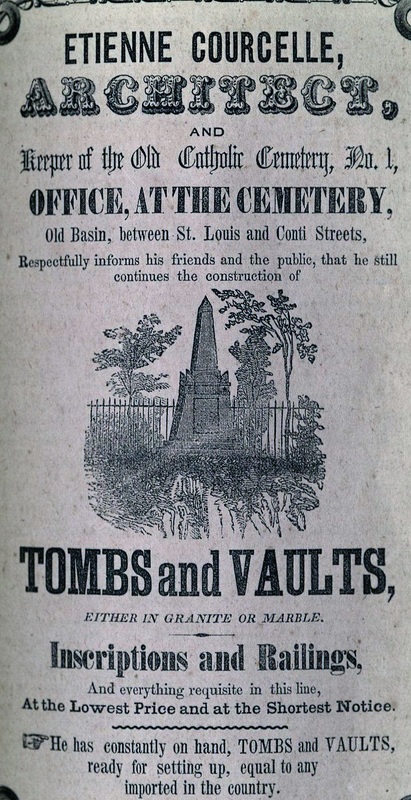

They form by the compression of these sediments, along with all the calcium-rich seashells within. They diverge when these sediments either compress and become sedimentary rock or, alternatively, are subject to higher pressures and become metamorphic. Limestone is sedimentary, marble is metamorphic. Limestone is most prevalent in the oldest remaining New Orleans cemeteries, namely St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, although precious isolated examples are found in other cemeteries. In this context, limestone was used for closure tablets. Limestone closure tablets are usually dark gray (likely quarried in Arkansas or Tennessee) and can be identified by the tiny fossilized shells included in the stone’s matrix. Around the mid-nineteenth century, whiter limestones were used in the same context as marble and are harder to identify. Some rough-faced stones that appear to be marble can be identified as limestone by spotting the shell inclusions within. These rare examples of white limestone were often quarried in Tennessee. Imported Marble: An Italian Commodity New Orleans was a primary hub for the import and export marble from both Europe and the United States. Used for closure tablets, shelves, memorial sculpture, apex sculptures, tomb cladding, and other decorative elements, marble was the medium in which cemetery stonecutters primarily worked throughout the nineteenth century. Based on documentary evidence, the quarries of Italy were the primary source of marble into the 1850s. Italian marble was either directly imported from Italy or arrived via northeastern ports like Boston or New York.[7] Florville Foy, who advertised aggressively throughout his career, frequently promoted his most recent shipment from Carrara or Genoa, cut into one, two, and three inch slabs. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux similarly advertised his Italian marble stock.[8] New Orleans stonecutters dealt in and imported Italian marble through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, stonecutter John Hagan (active 1854 – 1890s) stocked Italian marble “for sale at a small advance on New York prices.” George Stroud (active 1866 – 1899) cut his own Italian marble at Monsseaux’s steam cutting plant. James Reynolds (active 1866 – 1880) not only sold his Italian marble in New Orleans but also in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[9] Italian marble, often vernacularly referred to as “Carrara marble” regardless of its quarry of origin, is a stone of high-grade, consistent quality, and a variety of colors including cream, pure white, and blue. As one Alabama quarry owner conceded in 1909, “Italian marble has long been a standard, not only because the stone is undeniably high grade, but also because the blocks are so uniform in quality that all the slabs or pieces from a block can be used together.”[10] The cost of importing marble in New Orleans varied over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century; at times, it actually cost less to import than marble from Vermont or Tennessee. Protective tariffs helped to stabilize the marble industry during the 1880s and 1890s, but the presence of the famed marble remained a factor among monumental craftsmen into the present. For example, in 1914, before Albert Weiblen purchased his own marble quarry in Georgia, he received a shipment of Italian marble so substantial it took two large derricks to lift the fifteen-ton blocks from the steamship in which it arrived.[11] Domestic Marble: Vermont, Alabama, Georgia, and Others The slow development of infrastructure and quarry technology prevented American quarries from competing with Italian marble in New Orleans until the 1850s. In 1845, one of the first marble quarries opened in Talladega County, Alabama. Five years later, another opened nearby, operated by J.M.N.B. Nix. Using a publicity tactic that would become common among quarry operators in the United States, the New Orleans Daily Picayune announced that “Alabama produces marble equal in fineness – that is, purity or clearness and susceptibility of polish – to any in the world, not excepting the most beautiful Italian, Vermont, or Egyptian.” It was Nix’s quarry that sent Alabama’s contribution to the Washington Monument.[12] Talladega marble can appear white, blue, or cream, and often displays black, green, or grey veins, although it is consistently characterized by the fineness of its grain. Its unpredictability in quality and appearance, however, made it costly to extract.[13] Alabama marble remained a presence among New Orleans cemetery craftsmen well into the twentieth century. One of the most recognizable and imposing monuments within Metairie Cemetery, the ornate sarcophagus of Eugene Lacosst, was crafted by Albert Weiblen from pure white Alabama marble.[14] As always, infrastructure dictated which materials were available in New Orleans at a given time period. In 1851, The Vermont Valley Railroad Company connected towns like Rutland to the greater markets in the East and South.[15] Only two years later, sources in New Orleans commented on the great productivity of the Rutland quarries, remarking that their product had gained “a reputation abroad as well as at home.”[16] Rutland and other Vermont marbles can be white, blue, or black. These quarries also produced pure-white sculpture-grade marble.[17] By 1900, Vermont produced more marble than any other American state, and the Rutland quarry was the highest-yielding quarry. Blocks of Vermont marble were sold for between $1.00 and $3.00 per cubic foot in New Orleans, where agents received shipments and distributed order throughout the South and West.[18] Like Alabama marble, marble quarried in Vermont remained in the stockpiles of New Orleans craftsmen into the mid- and late twentieth century. Vermont not only exported its marble to New Orleans, but its marble cutters as well. One account reflected that the stone cutting yards of New Orleans primarily employed skilled sculptors and polishers from the states of Vermont and Georgia.[19] By 1916, Georgia was second only to Vermont in its production of quarried marble. Although marble quarrying had existed in Georgia long before, it appears to only have gained prevalence in the New Orleans market after the Civil War. By 1888, the Georgia Marble Company in Pickens County claimed to be the largest marble quarry in the world.[20] Georgia marble is typically coarse-grained and appears in blue-gray, black, white, and Creole, which has dramatic sweeping shades of dark gray, black, and white.[21] Ubiquitous Georgia Creole Marble Between 1890 and the 1930s, Georgia Creole marble exploded in the New Orleans cemetery market and made an enormous mark on the landscape. This explosion was the result of expert marketing, improved infrastructure, and enormous supply. Modern monument men during this period utilized Georgia Creole marble in nearly every aspect of their work, from tomb cladding to headstones to vases and urns. The streamlined process of tomb building, now executed in a more “cookie cutter” style than previous generations, allowed many more tombs to be built in a short period of time, and Georgia Creole marble was the medium of choice.

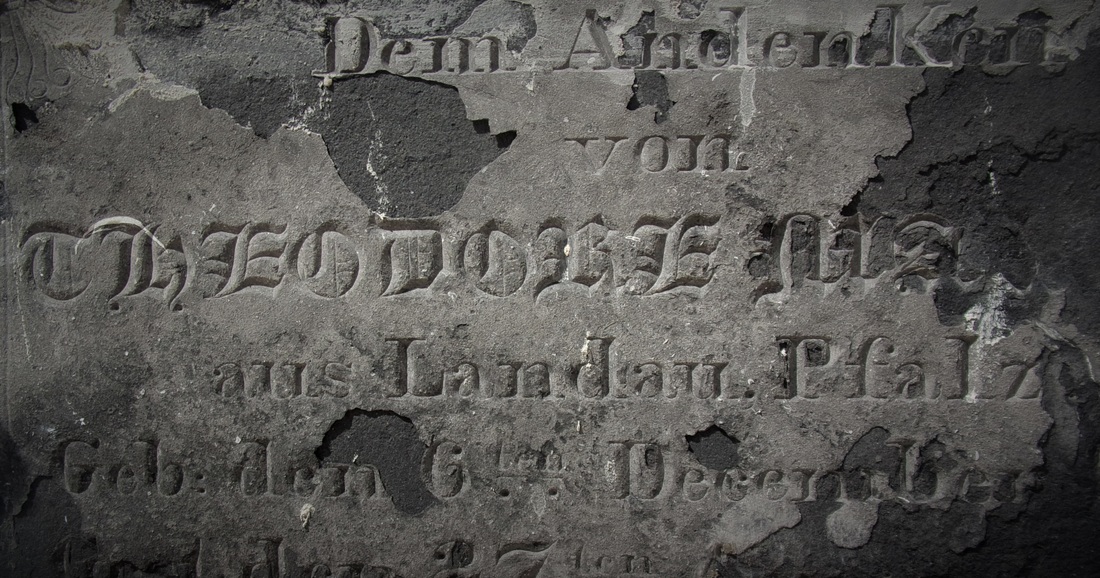

Additionally, as marble is a metamorphosed type of limestone, it is naturally alkaline in quality. Thus, exposure to rain, which is naturally slightly acidic, or any other acidic substance (for example, hydrochloric acid mistakenly intended to clean the stone) will cause marble to granulate and “sugar” over time. An extreme example of marble deterioration can be found in St. Joseph’s Cemetery No. 1. The failure that likely occurred with this stone was related to moisture entrapment within the tomb itself. This, paired with the tight, compressive position of the tablet within the opening, caused the closure tablet to bow and “bubble” outward.

One of the most noticeable granite tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is that of stonecutter and sexton James Hagan. This remarkable tomb was built of red-colored Scotch granite in 1872. Around the same time, Hagan also constructed the monument of Governor Henry Allen, which was also located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 until it was moved to the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the 1880s. This monument, too, was carved from Scotch granite.[24]

[1] Louisiana Geological Survey, Geology and Agriculture: A Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1902), 133-134.

[2] National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Northeast Region, Architectural Preservation Division, The Washington Monument: A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2005), 28. “Washington National Monument,” The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 22, 1850, page 1. The stone is referred to as “freestone,” meaning a soft, friable sedimentary stone. [3] Graham R. Thompson and Jonathan Turk, Introduction to Physical Geology (Rochester, NY: Saunders College Publishers, 1998), 133-137. Slate headstones are found commonly in the Northeast dating to the colonial period. Slate headstones are also present in cemeteries as far south as Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. However, no slate headstones are visible in the cemetery landscapes of New Orleans. [4] Mary Louise Christovich, Roulhac Toledano, and Betsy Swanson, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. I: The American Sector (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 1998), 57. [5] Daily Picayune, September 27, 1850, 2; Daily Picayune, May 2, 1853, 1; Daily Picayune, February 28, 1869, 11. [6] “Alexander Hill, Welsh and American Slates, Slabs, etc.” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 4, 1875, 6. These slates priced from $6.50 to $10 per square; “Slates! Slates! Slates!” Ouachita Telegraph (Monroe, LA), July 22, 1872, 2. [7] “Brig Casket arrives from New York with sundry marble slabs,” Louisiana Advertiser, April 29, 1820, 3. “Barelli & Company, commission merchants, selling blocks of Italian marble,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1845, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 10, 1848, 7; Daily Picayune, February 17, 1848, 3; Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1851 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1851), page AT. [9] Edwards’ Annual Director to the Inhabitants, Institutions….etc., etc., in the City of New Orleans for 1871 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1870), 275; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [10] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. [11] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8. [12] “Alabama Marble,” Daily Picayune, October 1, 1845, page 2; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [13] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. In this year, cost to transport Alabama marble to New Orleans was 32 cents per cubic foot. [14] Leonard V. Huber et. al. New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 54-55. [15] Vermont Railroad Commissioner, Eleventh Biennial Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of Vermont (St. Albans, VT: St. Albans Messenger Co., 1908), 308. [16] Daily Picayune, July 15, 1853, page1; Daily Picayune, June 16, 1855, 1. [17] Thomas Nelson Dale, The Commercial Marbles of Western Vermont (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 117-122. [18] Tariff Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means, Second Session, Fifty-Fourth Congress, 1896-97, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 275-279; “Random Notes,” The Reporter: The First and Only Journal Published in the World Devoted Exclusively to Granite and Marble, No. 1 (January, 1900): 33. [19] David Spence Hill, Industry and Education: Part Two of a Vocational Survey for Isaac Delgado Central Trades School (New Orleans: The Commission Council, 1916), 227. [20] “Science and Industry,” The Colfax Chronicle (Colfax, LA), November 3, 1888, 3. This was not an uncommon claim for many quarries to make. “Georgia Quarries,” The True Democrat (Bayou Sara, LA), January 30, 1897, 7. [21] Memoirs of Georgia, Vol. I (Atlanta: The Southern Historical Association, 1895), 211-217. [22] A. Oakley Hall, “Cities of the Dead,” in Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers Tales and Literary Journeys, Frank de Caro, editor. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998), 532-533; Arthur Wellington Brayley, History of the Granite Industry of New England, Volume I (Boston: National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913), 114. [23] Ibid., 84. [24] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley of Durham University, UK, for his knowledge and expertise in identifying the Hagan tomb as Scottish granite. [25] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1895), 1095. [26] “Notes from the Quarries,” Stone: an Illustrated Magazine Vol. 4 (1892): 496.

17 Comments

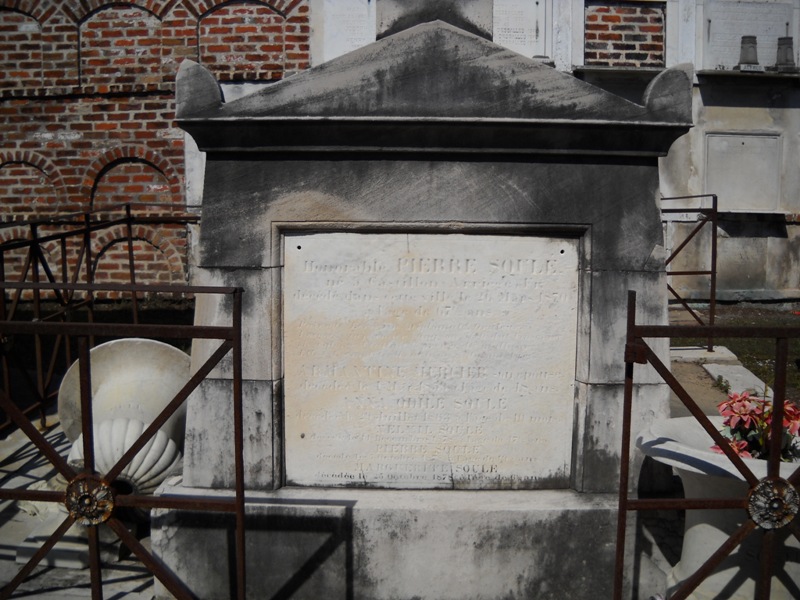

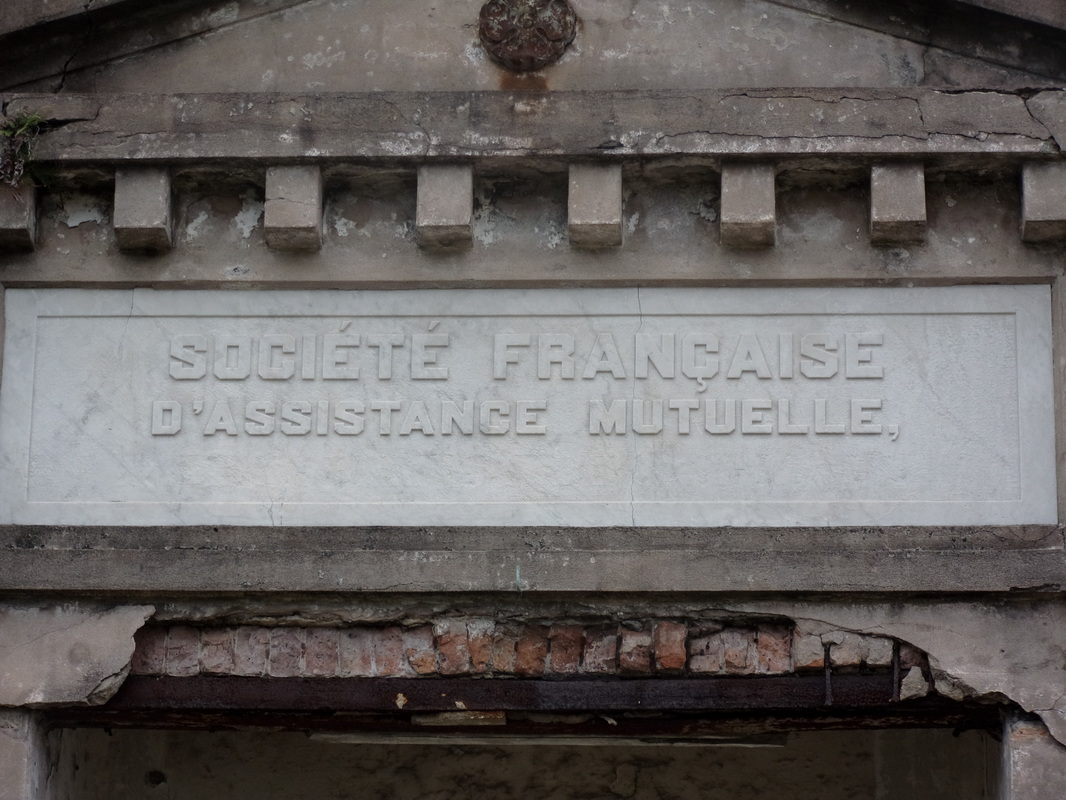

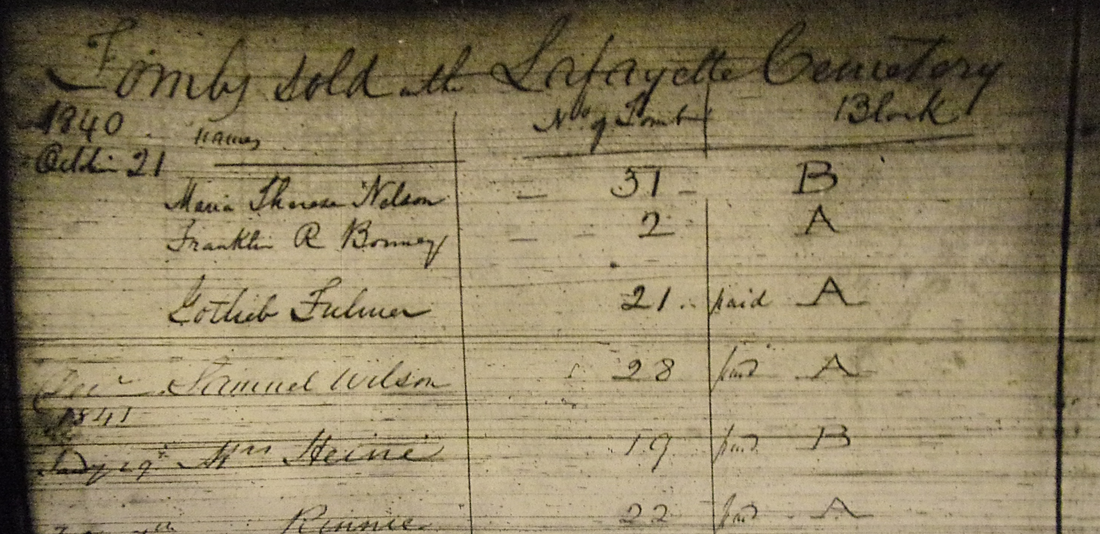

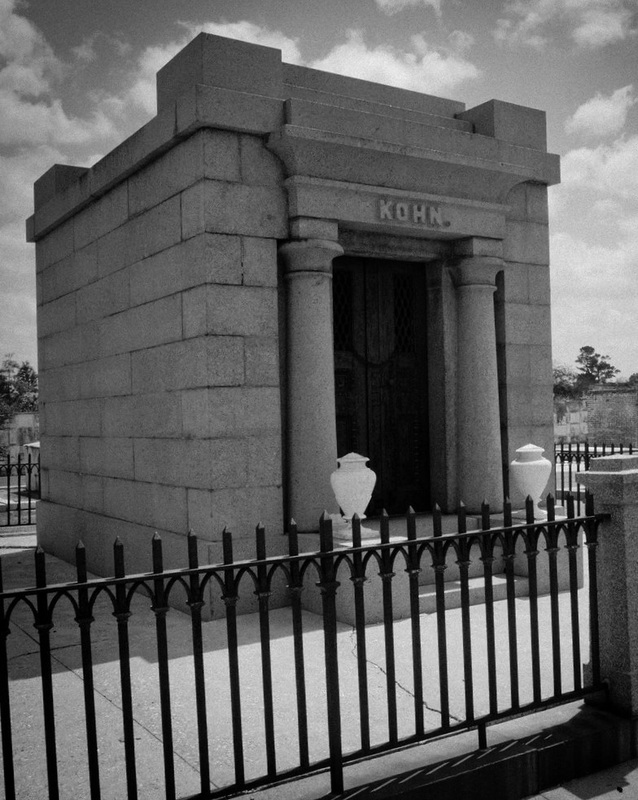

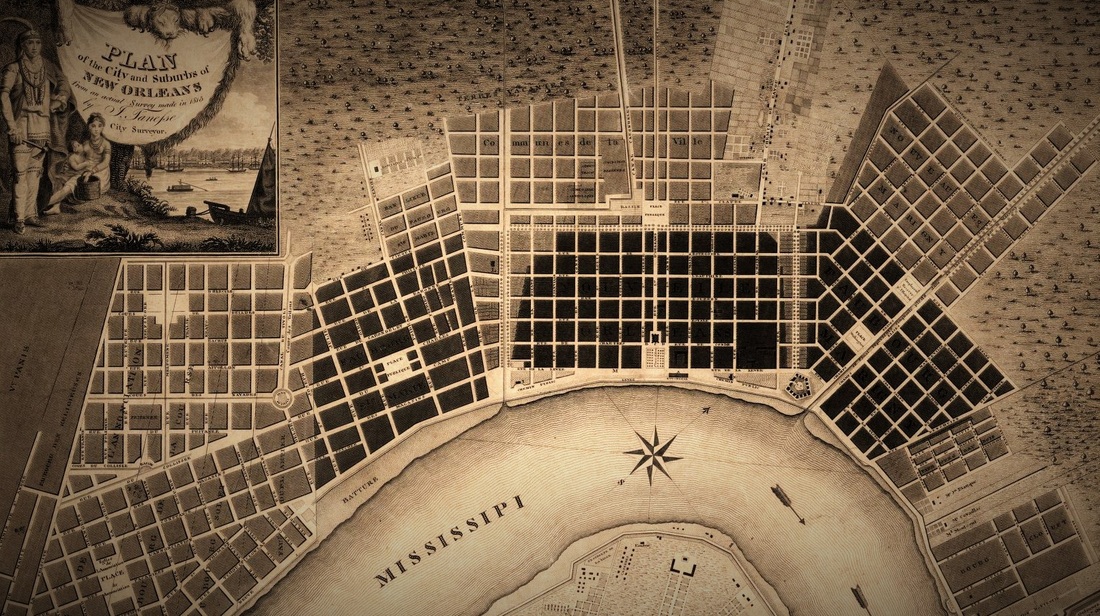

Recently, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC transcribed the burial records of the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, thanks in part to a grant from genealogist Megan Smolenyak. The Society was absorbed by the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans in 1900. Through this research and through extended investigation into the history of the society, its members, predecessors, and descendants, a rich portrait of the life of French-speakers in nineteenth- and twentieth-century New Orleans emerged. Today, we share the history of that society and its many milestones, members, and tombs. ARTICLE I: The association aims to improve physical, moral, and political fitness of its members; to lend each other assistance and relief in misery; to promote each other’s wellbeing, by council and by example; to collectively inspire the rights and freedoms of the home in all countries, and the practice of the duties, which alone can make them worthy; these are the primary obligations as members define them. – from the original constitution of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans, 1843 (translated from French).[1] The First French Benevolent Society in New Orleans On March 14, 1843, after four years of preliminary incorporation, the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (French Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society of New Orleans) was formally established with twenty-seven members. In its own words, the society formed as a result of increasing Americanization of the French colonial city after the Louisiana Purchase and into the Antebellum Era. The Sociètè Française was the first of many organizations in New Orleans with the aim of preserving French language and identity among its members. The Sociètè in New Orleans crafted their organization in the image of fraternal and masonic organizations in France, exemplified by the Grand Orient de France.[2] Similar values were emphasized: brotherhood, charity, social solidarity, and citizenship. The French model of freemasonry also emphasized laicity, or secularism. Among the founding members of the Sociètè in 1843 was a man who himself embodied the political nature of French freemasonry. Pierre Soulé (1801 – 1870) a French native and revolutionary who settled in New Orleans in the 1830s, shaped the early goals and tone of the Sociètè. However, he was elected to the United States Senate in 1847 and thus truncated his involvement. In this year, the Sociètè merged with the French Consulate. Minute books and histories of the Sociètè suggest that after Soulé’s departure, the political aims of the organization were abbreviated in favor of a charitable and social mission.[3] The Sociètè would come to be known for many things – its Bastille Day celebrations, its protection of the French language, its role as the French consulate for some time – but it was likely best known for its Hospital, which was an institution for over a century. French Hospital In the same year as the Sociètè’s founding, a French visitor to New Orleans donated thirty thousand bricks for the construction of a place in which the members could gather. The material was used to build the first French Hospital on Bayou Road near North Robertson Street, described by historians as “a center-hall, gable-sided, double galleried residence.[4]” The hospital, or Asile de la Société Française, cared for Sociètè members and their families. From 1847 to the early 1860s, the organization weathered multiple yellow fever epidemics in which as much as half of the membership was hospitalized.[5] In the early 1860s, the Hospital moved to St. Ann Street, a property donated by then-President Olivier Blineau. Blineau died shortly thereafter and was given the posthumous title of “Father of the French Society.” Originally meant only for society members, French Hospital was opened to all sailors of the French fleet in November 1862, in the event that an illness may require a stay on land.[6] With few exceptions, the Hospital was expressly for the use of members, their families, and those sponsored by members until 1913. In 1913, French Hospital expanded under the decision that “it was finally decided to build a clinic to treat strangers.[7]” Over the next thirty years, the Hospital would include a maternity ward, modern X-ray machines, and operation rooms. The original 1913 building became a well-known edifice on Orleans Street near Claiborne Avenue.[8] Tombs and Burial Benefits Throughout New Orleans history, it was common for societies to form around commonalities of nationality, profession, or background. Most societies would provide benefits similar to those provided by fraternal orders or by modern-day insurance companies. Among these benefits was frequently the option of burial in a society tomb, as well as funereal benefits for survivors. The Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans spared little time in establishing a society tomb for itself. On March 14, 1850, the Sociètè acquired a large lot in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 on Basin Street with the financial aid of the French Consul, M’r Roger. By August of the next year, the first stone of the tomb was laid at a formal ceremony. Beneath this stone, Sociètè officers laid a lead box, in which a copy of the organization’s Constitution, and parchment containing “the names of the President, members of the Consulate, and all members of the society” were placed.[9] The Classically-inspired tomb with an intricate sarcophagus at its apex was completed in the following years. In the early 1850s, the size of the tomb would have overwhelmed the landscape of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. The similarly-imposing Italian Benevolent Society tomb would not be built until 1857. The cross-gable roof of the tomb supported four cast-iron lamps (now missing), in addition to its large sarcophagus, giving it the appearance of a temple. Each corner of the tomb featured an upright torch fashioned of cast plaster. In historic photographs of the tomb, these torches were painted black.[10] In 1853 and 1856, President Blineau donated two additional lots in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 to the Sociètè. Either one of these donations may have been for the purpose of building an addition to the tomb. As is visible in the 1895 Library of Congress photograph, a smaller structure was built to adjoin the original tomb, comprised of fifteen vaults. This expanded the Sociètè’s burial capacity to seventy vaults, all of which could be reused over time.[11] Possibly as a result of a yellow fever epidemic in that year, rumors flew in 1867 that St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 would be permanently closed. In response, the directors of the Sociètè organized a picnic fundraiser to construct a new tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. The nearly $1,000 raised was utilized for the purchase of a lot, which was donated to the Sociètè. Mentions in Sociètè records as well as newspaper resources suggest that a society tomb was in fact built in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 for the use of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans. However, no tomb today bears the society name. The Sociètè maintained and repaired their tombs regularly, as was (and is) necessary with New Orleans tomb structures. In 1897 alone, the organization set aside nearly $500 por le fonds du Tombeau.[12] Regular limewashing, painting of plaster elements, cleaning of lamps and urns, and filling inscriptions with copper-based paint were annual expenses that contributed to the well-kept, beautiful structure seen in the 1895 Library of Congress photograph above. Funeral expenses were also part of member benefits. In an 1897 annual report, the Sociètè outlined these benefits specifically, including:

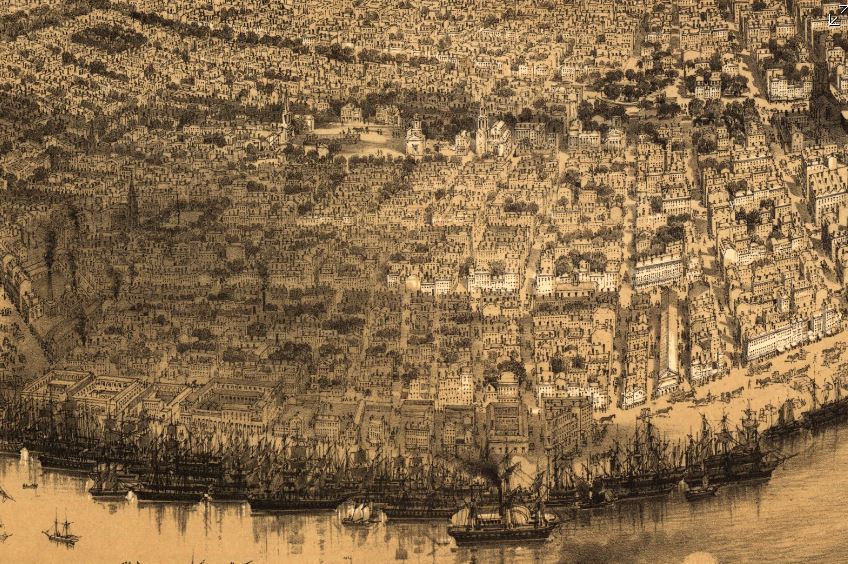

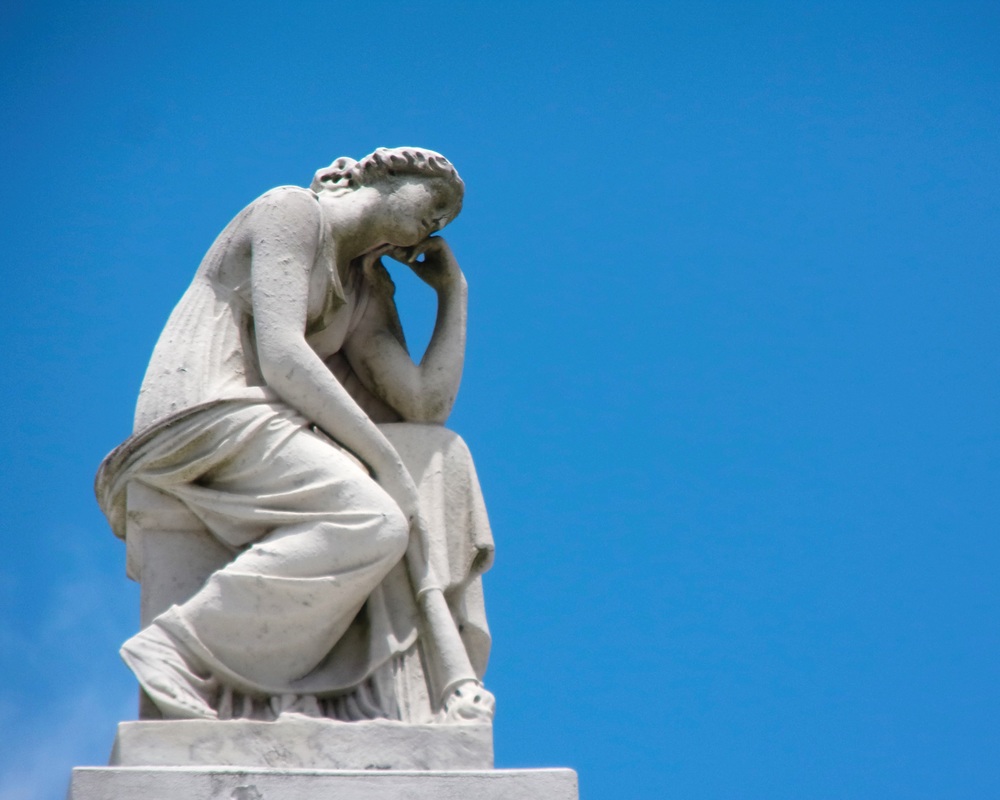

A Sister Society in Jefferson As the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans flourished through the 1850s and 1860s, an additional population of French-speaking people in what was then the City of Jefferson organized their own benevolent society. In the 1850s, the City of New Orleans was much smaller, and bounded on its upriver side by the Faubourg St. Mary and, farther upriver, the City of Lafayette. Over the course of the nineteenth century, New Orleans successively incorporated these municipalities into itself, creating the modern landscape of the city. Between modern-day Toledano and Joseph Streets, and bounded on the downriver side by the former City of Lafayette, the City of Jefferson was incorporated in 1850. Comprised of the Faubourgs Plaisance, Delassize, Bouligny, and others, the city would only remain independent for twenty years before being incorporated into the larger City of New Orleans.[13] It was here that the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson formed in 1868. The French speakers who lived Jefferson Parish and formed the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson were in many ways similar to their counterparts in New Orleans proper. In fact, in many cases they were related. Members of the Tujague and Carerre families joined and served as officers in both societies. Members of each group were often natives of the same departments in France, primarily the Pyrenees and Gers. Many had family in St. Bernard Parish as well as Orleans and Jefferson.[14] The Jefferson Sociètè was comprised of men who lived with their families “near the slaughterhouses,” or who lived on Tchoupitoulas, or near the St. Mary’s Market. They collaborated with and shared members with the Sociètè de Bienfaisance des Bouchers (the Butcher’s Society) who in 1873 brought the famous Slaughterhouse Case to the Supreme Court. A number of Jefferson Sociètè members were buried in the Butcher’s tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. The Jefferson Sociètè built its large, Classically-inspired, forty-vault tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 around 1872. The tomb is of extraordinary height, particularly in the landscape of this cemetery. Its primary gable pediment was carved with the name of the society, which once read “Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Ville de Jefferson,” although the “de la Ville de Jefferson” portion of the inscription appears to have been chiseled away after 1900. Below the pediment are stucco dentils, and on each side are cast-iron florets which likely cover structural tie-rods. The tomb has a number of unique additional features. On each side of its primary façade are niches which were once painted a brilliant Prussian blue, a historic pigment made with iron oxide. In each of these niches were marble statues of kneeling women, one of which had her hands raised in prayer, the other’s hands were crossed on her chest. Both of these statues were stolen between the 1950s and 1980s. The tombs gable-roof side projections hold most of its burial vaults, each enclosed in marble tablets and divided by slate slabs. All tablets of this tomb are uninscribed, leaving the names of those buried within to mystery until the recent transcription of burial books – which revealed the names of at least 150 people buried in this tomb between 1872 and 1900. The Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson participated in the celebrations of a number of French societies in the city. In addition to the New Orleans Sociètè, the Jefferson Sociètè was frequently documented in relationship with the Fourteenth of July Society and the Children of France. 1900: Merging of the Societies By 1896, at its twenty-seventh anniversary, the Jefferson Sociètè had “fifty or sixty” members – a roster that the Daily Picayune regarded as “not quite so large a membership now as at other times in its history.”[15] Officers from the Butcher’s Society and the New Orleans Sociètè, the French Orpheon, and the Fourteenth of July Society raised glasses of wine to the Jefferson officers B. Tujague, O.M. Redon, F. Desschautreaux, T. Abadie, and M. Despaux – most of whom would eventually be buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. It was only four years later that the dwindling numbers of the Jefferson Sociètè merged with their older counterparts at the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans. The merger was completed on January 3, 1901, which records report “brought 41 new members to the society. It also brought to the Society a tomb of forty vaults, nearly new, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2.”[16] The New Orleans Sociètè had merged with other organizations before, beginning with the French Consulate in 1847. In 1895, they also absorbed the Philanthropic Culinary Society of New Orleans, who brought with them an additional burial place: a five-vault tomb located in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street.[17] A Centennial Celebration and Gradual Decline While the New Orleans Sociètè had gained the members of its Jefferson counterpart, its own members were dwindling. This was the case for many benevolent societies in New Orleans after the 1930s. As the need for private hospitals waned, so did French Hospital. In the case of other societies who supported other causes such as orphanages or schools, the need for their ministries decreased with the rise of social services. As insurance corporations developed, private societies no longer fulfilled a necessity. For the French society, decreased interest in the French language likely took a toll, as the New Orleans Sociètè operated exclusively in that language. In 1943, the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (and, by merger, de la Ville de Jefferson) celebrated its 100th Anniversary.[18] A celebration was held at the French Hospital at 1821 Orleans Avenue, with a dance to follow at the American Legion. The festivities appeared to hold true to the organization’s civic dedication. French leader Andre Lefargue addressed the crowd with patriotic notions of the French and Americans once again fighting in a war together. Appeals were made to the crowd to donate to the Red Cross for the war effort. Nine French cadets training at the New Orleans Naval Air Station were special guests of honor.[19] Said society president Henry Bernissan at the centennial celebration, “the first 100 years of the society is merely the initial performance. We expect to improve our methods with every passing day.”[20] Yet the Centennial pamphlet published by the society seemed to suggest a different prescience: The current charter does not expire until the year 1972. Therefore, the Society has 29 years to run. It is hoped that the majority of the current members celebrating our centennial will prosper alongside the society until the end of its charter.[21] On October 31, 1949, only six years after its centennial, the closure of French Hospital on Orleans Avenue was announced.[22] The building was sold to the Knights of Peter Claver, an African-American Catholic Society, who utilized the building until the 1970s, when an adjacent structure was built. The French Hospital/Peter Claverie Building was demolished in 1986. The Knights of Peter Claver buiding remains on this site. The exact year in which the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans formally disbanded is unclear. Unlike their various balls, benefits, picnics and celebrations, this milestone in the organization’s history was not published in newspapers. However, it does not appear as if the Sociètè survived to the end of its charter in 1972. In a 1972 newspaper article, a passing reference was made to the Sociètè, “which for many years maintained the old French hospital on Orleans Street. The French Society folded a number of years ago.”[23] A Legacy of Burial Places Physical evidence of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle is scant in the landscape of modern New Orleans – except for in the cemetery. Each day, hundreds of visitors pass the Sociètè Française tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Without its cast-iron lamps and jet-black torches, it fades into the cemetery scene a little more than it once did, but it remains. For the more than 150 people buried in the Sociètè Française de Jefferson tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, that memory is much more tenuous. A number of trees that began growing in the tomb roof in the 1940s were cut down only this year, leaving a structure in significant need of repair. The brilliant colors of the blue tomb niches, the contrast of its white walls against black slate, its green copper drain pipes, have all faded to flat greys and exposed brick. Without names on the tomb tablets, it has been difficult for families to realize their ancestors are buried within. Yet with this project it is our hope that new resources will supply stakeholders with important information with which to regrow a connection to this remarkable structure, which represents more than a century of French fellowship in New Orleans. In our next blog post, we will share the lives of the people buried in this tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. The full burial rolls of interments into this tomb from 1872 to 1900 (up to the society’s merger with Sociètè Française d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans) have been uploaded to FindaGrave, in hopes their descendants may find them. The burial books are also available as an Excel Spreadsheet , MS Access Database, or PDF Document. Click here for burials listed by vault number. [1] Abrege Historique de la Societe Francaise d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, c. 1903, Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection. This and nearly all documentation of the Jefferson and New Orleans societies are entirely written in French. All translations by Emily Ford, who is by her own admission not fluent in French. Difficult phrases are presented in their original French in [brackets].

[2] Founded in the 18th Century, the Grand Orient de France permitted female membership by 1773. Documents of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans and of Jefferson suggest that neither society permitted female membership at any time. [3] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, published 1943 by the Sociètè, 9. Louisiana State University Special Collections, MSS 318, 1012. [4] Roulhac Toledano, Mary Louise Christovich, and Robin Derbes, New Orleans Architecture: Faubourg Tremé and the Bayou Road (Gretna: Friends of the Cabildo, 2003), 82. [5] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 19-21. [6] Ibid., 21. [7] Ibid., 39. [8] “New French Hospital Dedicated Yesterday,” Times-Picayune, February 24, 1913, 13. [9] Ibid., 15. [10] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 9. [11] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 19. [12] “Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, Rapport annuel, 1897,” Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection. [13] Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2008), 290. [14] From the records of Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson burial books, Louisiana State University Special Collections. [15] “The Old Jefferson Society Celebrates its 27th Birthday,” Daily Picayune, November 16, 1896, 10. [16] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 37. [17] Ibid., 35. [18] “French Unit Will Fete Centennial,” Times-Picayune, March 14, 1943, 11. [19] “Society Marks Centennial Day,” Times Picayune, March 15, 1943, 25. [20] Ibid. [21] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 51. [22] “25 years ago,” Times-Picayune, October 17, 1974, 19. [23] Times Picayune, September 24, 1972, 6. Find your tomb, Research your tomb, Restore your tomb The text below is excerpted from a recent presentation to the 2016 Annual Conference of the Louisiana Historical Association, presented by Emily Ford, MSHP, of Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LL New Orleans cemeteries are so unique that the simple mention of them creates a picture in one’s mind. That picture is likely one of intricate aisles populated by stately, yet crumbling, above-ground tombs; long abandoned, anachronistic cities of the dead which offer up stories through their carved tablets. Traditional histories of New Orleans cemeteries have been static, and ever tied to their place in popular culture. For example, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as part of what is now the Garden District. Over the next century, families built above-ground tombs ranging in style from simple masonry structures to grand Classical revival masterpieces. From this foundation, the interpretation of the cemetery usually branches into famous people buried therein, or a focus on specific architectural gems. These interpretations usually rely on a few primary sources. Some cemetery records, selected newspaper articles, and general contemporary observations of the cemetery as it exists in the moment tend to dominate the narrative. What few critical analyses of cemetery architecture exist tend to be repeated through numerous secondary sources. This tends to amplify their subjects as singularly important. For example, the excellent research of Patricia Brady on the stonecutter Florville Foy published in 1993 has been so revisited that the place of Foy among hundreds of other nineteenth century stonecutters appears paramount, as opposed to part of a larger craft community.[1] Beyond the few comprehensive histories relevant to New Orleans cemeteries lie the bulk of what is currently available – histories that focus on cemetery “residents” (for example, Marie Laveau or Colonel Harry T. Hays), high architecture, or the occult. These histories rely on the basic historiographies previously mentioned and typically add curious second-hand stories or rehashed false reports. For example, the translation of the tablet of André Valsin Labarre in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 has been repeated incorrectly for more than a century, but never once has it been noticed that it is located in the wrong lot.[2] Conversely, more dynamic and critical approaches to writing cemetery history will inevitably stumble upon landscapes which dramatically changed as their stakeholders did. For example, the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was not always one of above-ground tombs. The first stakeholders in this cemetery, predominately German and Irish immigrants, found above-ground burial to be perverse, and instead buried below ground. It was not until the 1850s, when their assimilated children gained control of the family lot, that tombs were constructed to emulate the New Orleans ideal.[3] Facts like this not only present a more accurate history of each cemetery, but also accentuate the changing uses each lot would see over time. Sale of lots, demolition of tombs, changes in materials, adaptive reuse, abandonment, and changes in technology are a constant presence in the history of any New Orleans cemetery. Consideration of these details empowers preservationists, stakeholders, and cemetery authorities to more appropriately care for these resources. By shifting the view of cemeteries from that of static landscapes (“outdoor museums”) to one of functional cultural resources, their history and their preservation are dually served. A critical approach to cemetery history combines a multifaceted catalog of primary resources. Original records vary in their condition and availability. With regard to tomb construction, cultures of craft typically focused on the final product and not on drawings, plans, or specifications. In order to piece together the history of a New Orleans cemetery, some creative and rigorous searching is in order. By pairing what primary resources are available with thorough and educated examination of the landscape itself, it is possible to determine the life story of any city of the dead. Original Cemetery Records There are between 32 and 46 historic cemeteries in New Orleans, depending on the criteria employed. Each one is unique in age, architecture, and culture. They also vary in terms of ownership and, thus, quality and location of records. In general, there are four types of cemetery ownership –

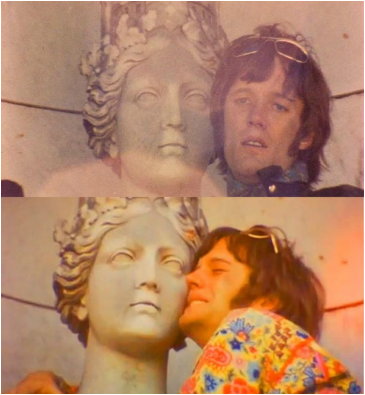

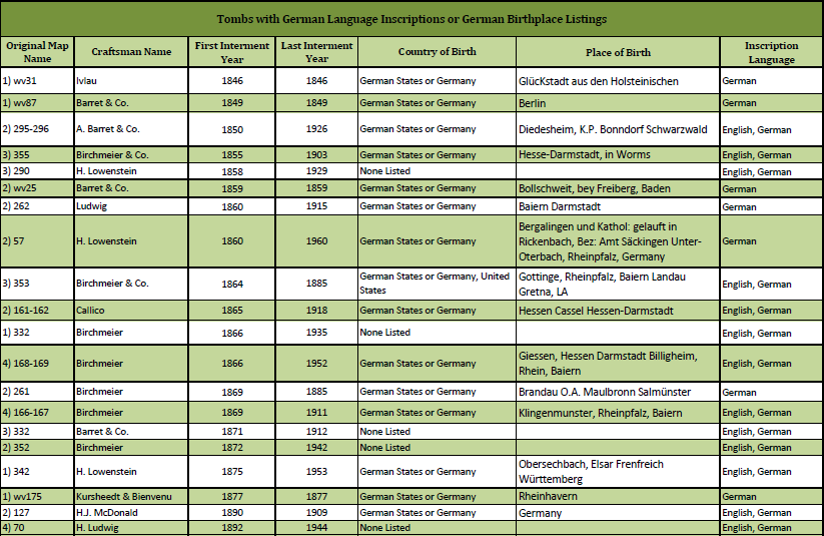

Records of cemetery burials, constructions, demolitions, or demographics were kept by the owning body of each cemetery. Owning bodies vary in their methods of access, preservation, and retention of records. Historic Images What cemetery records cannot contribute to the preservation and documentation of cemeteries is often accessible in a variety of traditional and non-traditional photographic resources. The use of historic photographs in the identification of property and the preservation of individual tombs has not been frequently visited. Furthermore, many photographs which can prove crucial to preservation efforts are difficult to find. When located, however, these photographs can tell the story of an entire cemetery, save a tomb from demolition, or re-unite a family with their property. The photographs of Clarence John Laughlin are an excellent example. Recently digitized by the Historic New Orleans Collection, the photographs date from the 1930s through the 1970s. Laughlin’s prolific hauntings through New Orleans cemeteries prove to be time capsules without compare. Identification of precise location of photographs yields not only histories of specific structures but also entire landscapes. For example, a 1920s postcard showing St. Roch Cemetery and a 1907 photograph of Holt Cemetery show an overwhelming prevalence of wooden markers. Comparison with present-day landscapes indicates enormous changes in the use of cemeteries over time – notably, the industrialization of the monument industry by mid-twentieth century. This shift overwhelmingly transformed cemeteries from highly individualized properties maintained by families to largely mono-stylistic landscapes maintained by cemetery staff – or not maintained at all. As we move into the twenty-first century, the presence of Hollywood in New Orleans cemeteries has created a new type of historiography. Productions like Easy Rider, Love Song for Bobby Long, NCIS, and dozens of others with scenes taking place in New Orleans cemeteries inadvertently document them. Easy Rider is a significant example. Fortunately for historians and preservationists, Peter Fonda’s place in the arms of the statue of “Italia” provides an image taken only years before a heavy-handed “restoration” permanently damaged it. Ephemera and Oral Histories Numerous resources exist beyond photographs and scant cemetery records. These require some amount of supporting evidence, and are best paired with observations of the built environment itself. Some ephemeral records were produced by the purchasers of the tombs themselves. Tomb deeds, once a common part of family papers, are rare, but those that do exist show that many tombs have a chain of title. Such evidence is also present in the notarial archives of tomb builders like Hugh McDonald, Paul Monsseaux, and James Hagan. The full potential of all of these resources is reached when paired with on-site examination of the landscape. This is achieved through painstakingly inspection of tombs for alterations, materials, and inscriptions. Larger-scale data collecting also proves fruitful. For example, while primary resources suggest stonecutter Anthony Barret predominately served a German-speaking market, database compilations of his signed work in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm the breadth of his presence in the German community. These conclusions are additionally supported by oral histories and interviews with the ever-dwindling community of cemetery craftsmen and caretakers, whose potential has rarely been formally tapped. In conclusion, the hidden historical record of New Orleans cemeteries reveals dynamic landscapes that were specific to their community, and constantly shaped by that community. By resurrecting these histories, which highlight stewardship, family involvement, and participation with cemetery authorities, these values can be preserved. Through these means, we can more accurately represent New Orleans heritage and community agency for those who take interest in it and are inheritors of it. Have questions about cemetery interment research or architectural histories of cemetery properties? Contact Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. [1] Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.: Master Marble Cutter and Tomb Builder.” Southern Quarterly 32, no. 2 (Winter 1993): 9-20.

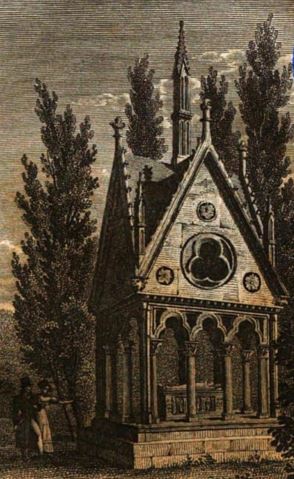

[2] Emily Ford, “André Valsin Labarre: Victime de Son Imprudence,” http://www.oakandlaurel.com/blog/andre-valcin-labarre-victime-de-son-imprudence (January 9, 2016). Based on in situ investigation, Archdiocese records, and 1930s WPA Index (housed at NOPL), this well-known tablet has travelled from Labarre’s actual resting place. [3] “History and Incidents of the Plague in New Orleans,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7 (June-Nov. 1853), 798; Bennet Dowler, Researches upon the necropolis of New Orleans, 22; George Edwin Waring and George Washington Cable, History and Present Condition of New Orleans, Louisiana, and Report on the City of Austin, Texas (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1881), 58; John Frederick Nau, The German People of New Orleans, 1850-1900, 15. Architectural histories within the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm this progression from below-ground burials to above-ground tombs and (eventually) copings. As any narrative on de Pouilly does, this article relies on the groundbreaking research and thesis of Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University thesis, 1992. Which exquisitely analyzed de Pouilly’s work in New Orleans cemeteries. One hundred and forty years ago, on February 21, 1875, Jacques Nicholas Bussiere de Pouilly died in his home on St. Ann Street. In his seventy years of life, de Pouilly had been the harbinger of European neoclassical and revival architecture in New Orleans. We see his touch on our city streets – in St. Augustine Catholic Church, and most notably St. Louis Cathedral. But his influence was arguably greatest in the city’s cemeteries. De Pouilly’s work is present in nearly every viewpoint of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, and much of Cypress Grove Cemetery. The breadth and innovation of his tomb architecture generated uncountable replications and inspirations, the products of which have shaped our burial grounds. J.N.B. de Pouilly was born in July 1804 in Châtel-Censoir, France, southeast of Paris. While much of his early life is unclear, it is assumed that in his architectural training he was influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, if not a student of the school himself.[1] He arrived in New Orleans in 1833, a time in which the French-speaking population of the city hungered for reconnection with Continental styles. He quickly became the architect of note for the city’s First District, designing the St. Louis Exchange Hotel, among many other residential, commercial, and religious projects.

While Père Lachaise and Creole cemeteries like St. Louis may appear stylistically similar, de Pouilly had the significant task of fundamentally shifting the function of his New Orleans tombs from their Parisian prototype. Although the monuments of Père Lachaise appear to be tombs or mausoleums, their design accommodates instead for below-ground burial. That the architect’s designs kept their Parisian aesthetic while having been fundamentally re-worked to allow for above-ground burial is among the more impressive of his professional achievements.[3]

In addition to the French St. Louis Cemeteries, de Pouilly worked also in American-dominated Cypress Grove Cemetery (est. 1840). In Cypress Grove, de Pouilly additionally contracted with granite magnate Newton Richards to build the memorial of fallen firefighter Irad Ferry (died 1837). He relied, too, on Monsseaux and Foy to construct such masterpieces as the Maunsel White tomb. De Pouilly clearly had a strong grasp on the value of trade and materials, based on his choice of craftsmen and his apparent innovations in the world of cast stone. De Pouilly’s career was marred by two construction disasters in the 1850s – first, the collapse of the central tower of St. Louis Cathedral while de Poilly was head architect, and second the collapse of a balcony at the Orleans Theatre. From this point onward, his rising star waned, but it appears never to have faded in New Orleans cemeteries. In 1874, de Pouilly composed the final drawing in his only surviving sketchbook – a tomb he designed for himself and his family. This tomb, like many depicted in his prolific sketches, would never be constructed. Instead, de Pouilly was interred in a family wall vault in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Although the location was surely not intentional, the wall provides a lovely view of a number of de Pouilly-designed tombs. In a nearly-illegible detail to his memorial tablet, the signature of Florville Foy can be detected as the carving hand of de Pouilly's final tablet. De Pouilly’s obituary on February 22nd spoke grandly of a man who lived honestly and in service of his profession:

St. Peter’s lofty dome cenotaphs the name of Michael Angelo [sic]: Sir Christopher Wren’s greatness is sepulchred in the mightiness of St. Paul’s. Mr. De Pouilly fashioned no wonders such as these, but yet a greater, the enduring fabric of an honest life, and will be entombed in the constant remembrance of devoted friends. After a painful and lingering illness, Mr. De Pouilly, hoary with the winters of seventy years, and surrounded by children and other relatives, bade farewell to things of earth. This sad event occurred yesterday, Sunday, 21st.[4] The Daily Picayune made no note of the many cenotaphs de Pouilly himself had helped write, in the tablets and along the aisles of our cemeteries. But if 140 years is a sufficient measure of the timelessness and impact of one’s work, his name certainly engraved upon many more memorials than just his own. Below is a gallery of only a portion of de Pouilly’s work, and a few tombs inspired by his designs. Photos by Emily Ford unless otherwise noted. [1] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” 5-7.

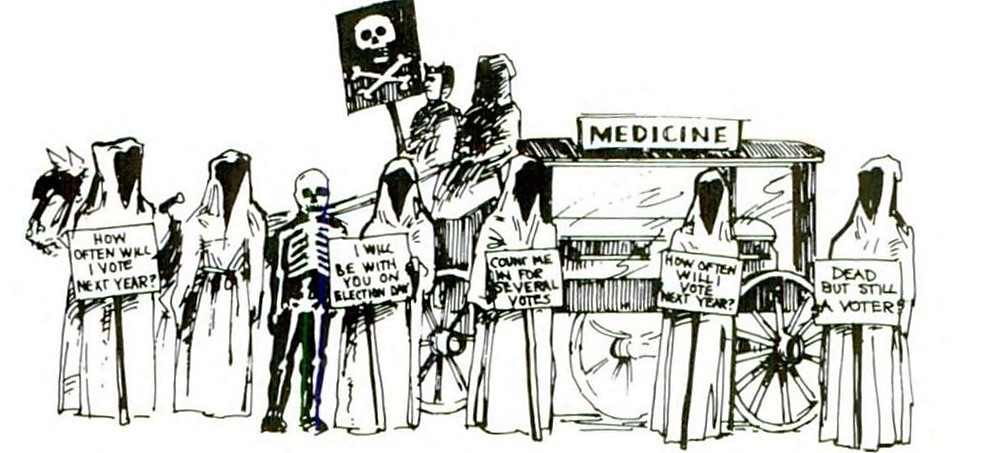

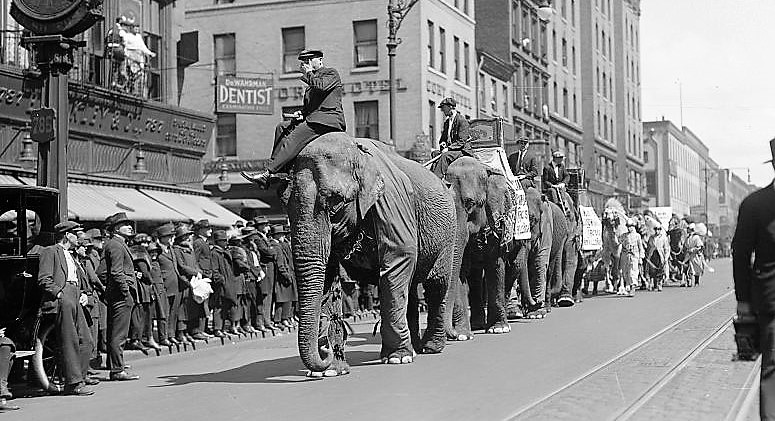

[2] Peggy McDowell and Richard E. Meyer, The Revival Styles in American Mortuary Art (Popular Press, 1994), 59. [3] Masson, 30-35. [4] “In Memoriam – J.N. de Pouilly,” Daily Picayune, February 22, 1875, 2. Over the past week, New Orleaneans have been treated to nightly parades in neighborhoods Uptown and downtown, on the West Bank and in Metairie. Today, Krewe of Thoth will ride down St. Charles Avenue, followed by Bacchus and others this evening. The fever pitch of Mardi Gras is upon us, culminating on Fat Tuesday, Mardi Gras Day. In the spirit of the season, we’ve mused on the place of cemeteries in Mardi Gras traditions – from the last resting places of Dead Rexes to the incorporation of death and cemeteries in costuming and floats. Seldom do Mardi Gras celebrations themselves take place in New Orleans cemeteries. But once or twice in a blue moon, amidst Storyville revelry or between the pages of a Gayarré novel, such things have happened. Today, on this Sunday before Mardi Gras, we explore the few instances of Mardi Gras dancing on the graves. The St. Louis Cemetery Marchers In one of the St. Louis Cemeteries, the dead were entertained by an especially satirical parade in 1911, when maskers dressed as deceased voters processed through the cemetery gates to follow the tail of the parade of Rex. The details of this event are discussed in two New Orleans histories, although primary accounts of the parade are scant. In what James Gill refers to as one of the “drollest examples” of political satire in Mardi Gras parades, marchers dressed as skeletons emerged from the cemetery holding signs marked, “Count me in for several votes,” “I’ll be with you on election day,” and “Dead, but still a voter.”[1] According to Buddy Stall’s New Orleans, the marchers labeled themselves “The Graveyard Pleasure Club,” “Girod Cemetery Voters League,” and “the Tombstone Brigade.”[2] The members of the St. Louis Cemetery Marchers were anonymous, although one marcher later revealed his identity to be Edouard F. Henriques, a local judge. He and other members were members of the Good Government League, part of the Progressive movement in Louisiana and, in the next year, supporters of “Bull Moose” presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt, much against the dominant Democratic "machine" in New Orleans. The Marchers emerged from St. Louis Cemetery (presumably No. 1, or possibly No. 2) after having “entertained the sexton” with their antics. They caught up to Rex and followed along its route, as one parade-goer remarked, “Their silent message is more meaningful than any spoken word I can imagine.” They continued behind the parade until police forces peacefully disbanded them, just before they reached City Hall. The Elks Burlesque Circus In the days leading up to the St. Louis Cemetery Marchers 1911 procession, a bigger, louder ruckus was taking place just blocks away. At Elks Place and Canal Street, a great circus would take place, complete with lion tamers, elephants, and acrobats. On the Friday before Mardi Gras, this circus paraded through the city, marching uptown as far as Felicity Street, and back through the Central Business District.[3] The enormous circus and parade were organized by the New Orleans Lodge No. 30, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, known casually as the Elks Lodge, and for whom Elks Place is named. If you live in New Orleans, you probably know them for their tomb, which looks out on the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The 1911 circus and parade, complete with a petting zoo of baby elks, was held as a fundraiser for an imposing tomb the Elks Lodge hoped to construct in Greenwood Cemetery. Elks members costumed as clowns and even traveled abroad to learn how to care for circus animals – said one article, “Quite a number of the antlered herd are taking corresponding lessons on how to manage elephants and camels.[4] The big top Mardi Gras-season fundraiser was as ambitious as the organization’s tomb plans. The Elks Lodge memorial is a tumulus: a burial chamber which has been covered in earth, making it resemble a hill or burial mound. While New Orleans is no stranger to tumuli – at one point in time, they were quite common in cemetery landscapes – the Elks Lodge tumulus is one of the most iconic of these structures in American cemeteries. The tumulus was constructed by Albert Weiblen at the cost of $10,000 – essentially $250,000 in 2016 dollars.[5] Its subterranean walls were topped with a giant boulder of Alabama granite, on top of which a nine-foot-tall bronze elk was erected. Two years and some minor (but noticeable) foundational issues later, the cemetery landmark was completed. Today, organizations with communal tombs and society burial places often find great difficulty in raising the capital needed to restore their deteriorating cemetery property. Perhaps it’s time once again to bring the circus to town for the benefit of our historic cemeteries. Tintin Calandro: The Mad Musician of the St. Louis Cemetery Our final Mardi Gras cemetery story is exactly that: a story. On this blog, we like to keep things factual, but in the spirit of the prankishness and surreality of Carnival, we recall the tale of Tintin Calandro. Celebrated New Orleans author Charles Gayarré (1805 – 1895) is memorialized in the city as its premiere 19th century historian. A beautiful terra-cotta memorial to him sits at the divergence of Esplanade Avenue and Bayou Road. He is best remembered for his History of Louisiana (1866), but he did write two novels as well, Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction (1872) and Aubert Dubayet (1882). Featured in both of these novels is Augustine Calandrano, more frequently referred to by the narrator as Tintin Calandro, French revolutionary exile, talented violin player, and eccentric sexton of St. Louis Cemetery. In Fernando de Lemos, Tintin Calandro is a “genius of madness,” each night serenading his ghostly charges:

Calandro and Fernando de Lemos have a special relationship in which they spend nights in the cemetery, discussing philosophy, love, ethics, and other profound topics amidst the tombs. Toward the end of Calandro’s life, it appears his fits of insanity worsened. Nearing his own death, the old sexton fought frailty and his better senses in order to go to the cemetery for a final concert, on Shrove Tuesday: He said that the ghosts were going to have a Mardi Gras ball and he wanted to open the event by playing an overture, after which an orchestra of spirits would supply the music… [the narrator] accompanied the musician to the cemetery. There Tintin greeted the ghosts, bade them be silent and seated, and then seating himself and his companion on a tombstone, he began to play. … In the spell which overcame him he saw the ghosts whisking past in the dance, and the mad excitement grew upon him until the sound of the violin was hushed. Then Tintin apologized to his visionary audience, and allowed his friend to escort him home.

[1] James Gill, Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans (University Press of Mississippi: 1997), 166.

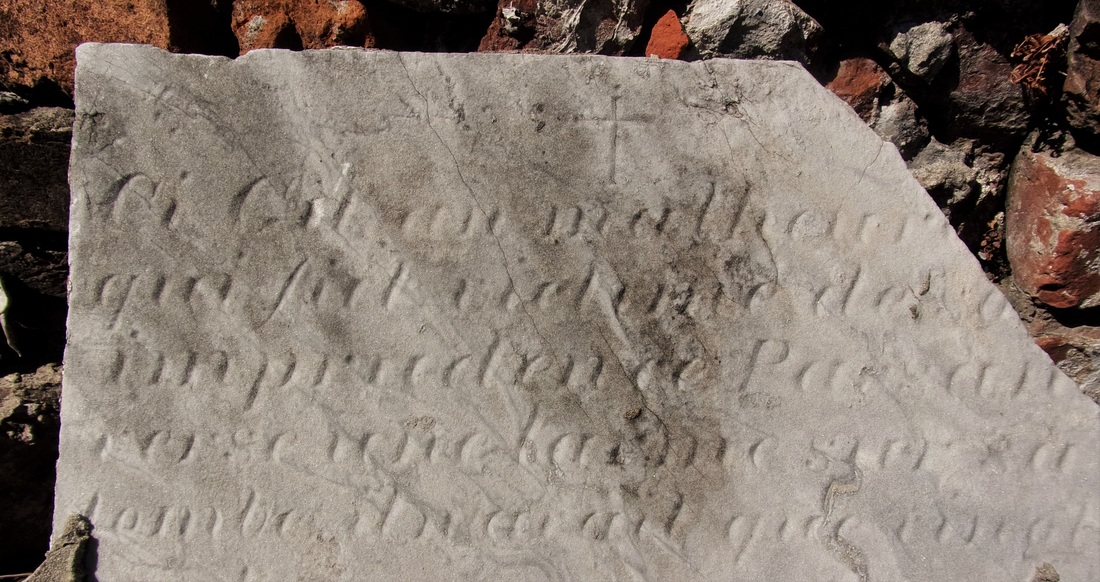

[2] Buddy Stall, Buddy Stall’s New Orleans (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1990), 167-169. [3] “Elks Announce Route of Parade Preceding Burlesque Circus,” Daily Picayune, February 20, 1911, p. 2. [4] “Elks’ Circus to be a Feature During Carnival Week Here: Parade and Performances to be Filled with Features Farcy, Freakish and Funny,” Daily Picayune, January 15, 1911, 30; “Circus Catches: Pokorny’s Little Elks Arrive for Big Show,” Daily Picayune, February 17, 1911, 7. [5] “Elks’ Tomb to be Erected on Fine Greenwood Cemetery Site,” Daily Picayune, August 7, 1911, 7. [6] Excerpt from Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction, featured in The Southern Bivouac, Vol. II, No. 1 (June, 1886), 112-114; James A. Kaser, The New Orleans of Fiction: A Research Guide (Scarecrow Press: 2014), 92. [7] “Tintin Calandro: Judge Gayarré Tells the Story of the Mad Musician of St. Louis Cemetery,” Oachita Telegraph, January 20, 1887, 1. Special thanks to Mary Lacoste, author of Death Embraced, for drawing our attention and curiosity to Mr. Labarre. On any given day in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, hundreds of people walk down a back alley toward the “Musicians’ Tomb.” Led by tour guides, they may stop at a newly constructed-tomb or point out a newly-restored one. A few point out the tablet of André Valcin Labarre. One tour guide points to the loose-lying, grey-veined little tablet and states, “He was a bad boy,” as they walk past. The tablet is leaned up against a structure that has likely not been tended for nearly two hundred years. Half-collapsed, it is hardly a tomb any longer. Like uncountable burials in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, it is on its way to becoming completely erased. But Labarre’s tablet remains. Now broken and missing a piece, the Labarre tablet has long been referred to as among the most interesting in the cemetery. Its French inscription is difficult to read, let alone translate, but the words “victime de imprudence” remain visible. These three words have made the tablet a sensation, although nearly all accounts of its message have been incorrect. In a way, this is a story of a man who died young and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. But if this was all there was for André Valsin Labarre we wouldn’t be intrigued by him today. Instead, this is also a story of how one man’s epitaph led to a century of confused transcriptons, translations, and misunderstandings. In the nearly two centuries since his death, he continues to sow imprudence.

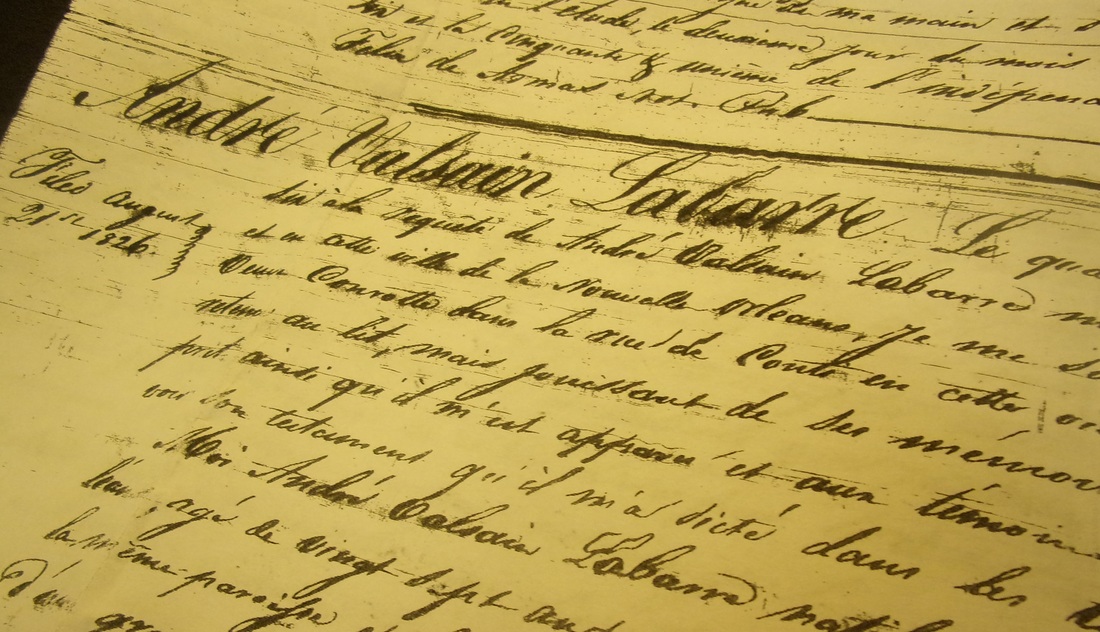

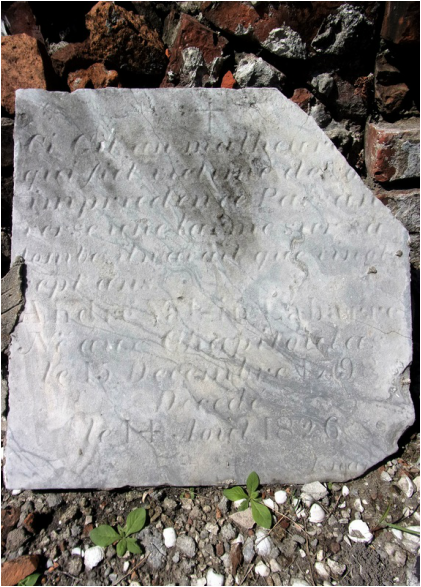

From the mid-1700s, the Labarre family owned significant holdings of land in what would become Jefferson Parish. Beginning with Francois Pascalis de Labarre Sr., who served law enforcement and municipal roles, a number of Labarre men claimed the post of sheriff in Jefferson’s early days.[2] Biographers and genealogists refer to the Labarre family as tied to their land, known as Chapitoulas Plantation or the Chapitoulas Coast.[3] The property line for this plantation is still demarked as Labarre Road in Jefferson. The family’s ancestral home, White Hall, is now home to the Magnolia School. André Valsin Labarre (usually addressed as simply Valsin) was born on December 15, 1798 at Chapitoulas Plantation. He is described as having less attachment to the plantation homestead than his parents, siblings, and cousins. According to one genealogist, Valsin was “the first of the Labarre family to move back to the city” of New Orleans since Franscois Pascalis Sr. purchased the Chapitoulas plantation in 1750.[4] Labarre lived in the Faubourg Marigny in 1822, when he married Virginie Conrotte (c. 1808-1850). The two had only one child, Samuel Placide Labarre, born December 4, 1822.[5] As for what André Valsin Labarre could have possibly done to deserve a tablet that suggests he died of his own imprudence, there is no clear answer. As we will see with later interpretations of his tablet, much is up for conjecture. His will shows a fondness for fine possessions: a “big horse of superior quality,” Spanish saddles and riding gear, a double-barreled hunting gun. He also owned five slaves: Fortune (30 years old), Thom (28), Constant (18), Maria (19), and Eliza (15). Thom and Fortune were “carters,” leading some to assume they “operated a cart and sold goods for their master.[6]” Beyond this means of income, it appears Valsin held no definite occupation, suggesting he may have been a man of leisure who enjoyed fine guns and horses.[7] On July 14, 1826, notary Carlile Pollock visited twenty seven year-old André Valsin Labarre at a home on Conti Street, likely the home of a relative.[8] Pollack was called to the house by Virginie Conrotte. Wrote Pollack: on j'ai trouvé le requerant malade retenir au lit, mais jouissant de memoire et entendement naturels, et bien d'esprit “there I found the sick man confined to his bed, but sound of memory and understanding, and in good spirits.” Pollock had been called to compose the last will and testament of André Valsin Labarre. In this will, Labarre named his oldest brother, Francois Pascalis Labarre II, executor and beneficiary of his property. He also requested that his brother care for his widow and son, Samuel Placide Labarre, and see that his son completed proper schooling.[9] No record documents exactly what had caused his illness. Valsin died on Monday, August 14, 1826, one month after writing his will. His obituary in La Courier de Louisiane only confounds the possible cause of his death, but describes him fondly: Mr. Valcin Labarre est décédé Lundi soir, à l'age de 27 ans, a la suite d'une longue et cruelle maladie. Doué d'une excellence constitution et a fleur de l'age, il semblant devoir fournir une longe carriere dans cette vies mais une entiere negligence de lui-meme a donné prise a la fatale maladie qui l'enleva a une nombreuse et respectable famille, a une interessant et jeune espouse, et un enfant en bas age. Mr. L. avait d'excellentes qualites qui le font regretter d'un nombreux cercle d'amis. “Mr. Valcin Labarre died Monday night at the age of 27, following a long and cruel illness. Endowed with an excellent constitution and in the flower of his age, it seemed he should have had a long career in his life, but a complete negligence of himself gave rise to a fatal sickness which swept him away from a large and respectable family, young and caring wife and a small child. Mr. L’s brilliant qualities will be missed by a large circle of friends.”[10] The Epitaph This sense of wasted potential is echoed in the poignant tablet his family erected at his grave. After close study of the tablet, as well as all past transcriptions of it, this is the epitaph carved for André Valsin Labarre:  Ci Gît un malhereux qui fut victime de son imprudence. Passant, verse une larme sur sa tombe, il n’avant que vingt sept ans. André Valsin Labarre Né aux Chapitoulas le 15 Decembre 1798 Decedé le 14 Aout 1826 Here lies an unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Passerby, shed a tear upon his grave, he was only twenty seven years old. André Valsin Labarre Born at Chapitoulas December 15, 1798 Died August 14, 1826 Labarre’s tablet was carved by Jean Jacques Isnard from gray marble. Isnard (1779-1859) was one of the earliest stonecutters in New Orleans. His prolific work can be found throughout St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Valsin’s death and burial in 1826 was the end of a short, but presumably happy life. His cause of death will likely remain a mystery. “Indiscretion or Excess” The phrase “victim of one’s own imprudence,” appears in rather specific narratives in the nineteenth century. It suggests a negligence of self-care by way of excessive living or failure to treat illness in its preliminary stages. For example, a woman who dies of consumption because she did not treat a cold was a victim of her own imprudence. Alternatively, the term “victim of imprudence” was frequently used in advertisements for men who had contracted venereal disease. In the case of Labarre, others have suggested perhaps the excesses of drink, although no record can confirm. For whatever reason, Valsin’s family requested such language for his tablet. Little would they know that the words they paid Isnard to carve would become somewhat of a legend a century later. A Travelling Tablet Perhaps the greatest mystery of all, however, is where Valsin himself was originally buried. A survey completed in the 1930s notes the tablet to be located in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, Aisle 8-R, although it does not specify lot number. Today, Valsin’s tablet is located in Aisle 7-R. Unfortunately, the original cemetery records for 1826 do not specify lot number. While we may love Valsin’s immortal eulogy, his mortal remains may never be located for sure. One Hundred Years of Mistranslation Nearly 75 years after Valsin’s death, in 1900, the New Orleans Daily Picayune wrote a full-page piece on local cemeteries in honor of All Saints’ Day, November 1. This was a common annual occurrence in which newspapers would describe the scene at each cemetery, noting curious epitaphs or beautiful new tombs. With this article, Valsin’s memory was revived in a very peculiar way: On one old slab, almost defaced with age, is the inscription “Ci git un malhereuse qui fut victim de son imprudence. Verse un larme sur sa tombe, et un ‘De Profundis’ s’il vout plait,” por son ame. Il n’avait que 27 ans, 1798.” The translation reads: “Here lies a poor unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Drop a tear on his tomb and say if you please the Psalm, ‘Out of the Depths I Have Cried unto Thee, Oh, Lord’ for his soul. He was only 27 years old.[11] Three years later, on November 2, 1903, the Picayune printed the exact same paragraph in another All Saints’ Day article. This printing birthed two widely-repeated falsehoods regarding Labarre – that he had died in 1798 (the year he was born), and that the tablet had an additional line regarding a psalm, which it clearly does not. This misunderstanding would perpetuate itself, making scholars and authors truly the victims of their own imprudence. In 1919, a tourist brochure said of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1: “The inscriptions are in French, and many of them tell how he who sleeps beneath ‘fell in a duel, the victim of his own imprudence.[12]’” It is unclear if this is directly inspired by Labarre or perhaps another now-missing tablet. Unfortunately, even the most revered of New Orleans cemetery texts replicate to the Labarre myth. In one seminal 1974 book, the authors suggest again that Labarre’s is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, quoting the Picayune article. The text also muses that perhaps the poor fellow had died in a duel. From 1974 to 2004, three other publications cite this faulty article, each suggesting that it is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, and that the deceased had met his end in a duel. One insists that the tablet is long lost to history. All this time, André Valsin Labarre’s tablet has sit idly by as tour groups wind in and out of the cemetery aisles.

New Orleans cemeteries typically identify the owners of tombs by direct lineage. Through this lens, there are no descendants to claim care of the prodigal son’s tablet. Valsin’s son, Samuel Placide Labarre, married Emma Labranche in 1866. Their union produced one son, who Samuel named after his father, Valsin. Valsin Labarre died around 1890. There is no indication that he married or had children. Additionally, Virginia Conrotte remarried after Valsin’s death. She and her new husband, Daniel Gregoire Borduzat had at least four children. Unfortunately, the surname Borduzat appears nowhere in indexed cemetery records. If indirect relatives to Valsin Labarre remain, they have not reconnected with his burial place. Both the tablet to his memory and Valsin himself have become, in a sense, immortal for the most peculiar of reasons. Yet their fate remains suspended between the aisles of New Orleans' oldest cemetery, awaiting the next chapter in their story. [1] Stanley C. Arthur and George Campbell Huchet de Kernion, Old Families of Louisiana (New Orleans: Harmanson, 131), 98-104.

[2] Arthur and Campbell, 98. [3] William Reeves, De La Barre: Life of a French Creole Family in Louisiana (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1980), 79, 88. [4] Reeves, 88. [5] Reeves, 175. [6] Reeves, 119. [7] Probate inventory of André Valsin Labarre, New Orleans Public Library microfilm KR 308, Old Inventories, Vol. L, 1821-1832. [8] 1821 New Orleans directory, Louis Labarre, No. 14 Conti. [9] New Orleans will documents, New Orleans Public Library, VRD410, 1805-1833, Recorder of Wills, Vol. 4, 106. [10] La Courier de Louisiane, August 16, 1826, 2. Accessed via microfilm, New Orleans Public Library. Translation composite of a number of translations from French speakers, William Reeves, and Emily Ford. [11] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1900, 3. [12] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “In Old New Orleans,” from Travel, Vol. XXXII, No. 4 (Feb. 1919), 26. The third in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. 23,707 infected. Not less than 4,600 dead. Such was the toll of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in New Orleans. The Crescent City was ground zero – the first point of contact in the United States for an epidemic that swelled north and eastward from July through November, taking 20,000 souls in total. Dozens of burials in each cemetery each day led one report to state that, in a sense, each day of the summer of 1878 had been All Saints’ Day. On the day of the holiday itself, many graves still retained the decorations of burial.[1] And the epidemic was not even completely over.

In the days leading up to All Saints’ Day, some health officials even cautioned against the yearly tradition of decorating and caring for loved ones’ graves. Said the Daily Picayune: It should be mentioned… that some physicians are of the opinion that, owing to the extraordinary number of interments during the summer and the prevalence of infectious disease, it would not be safe for a general decking of graves to be carried out as on occasions of the past.[2] |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly