|

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb.

2 Comments

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. Beyond sweeping landscapes and imposing architecture – within the “stories in stone” that are so beloved in New Orleans cemeteries, are the stones themselves. Much like the long-dead people they memorialize, these slabs of honed and carved limestone, marble, and granite journeyed great distances to become part of an irreplaceable cemetery landscape. Whose hands drew that stone from its quarry? Why is the marble found in Greenwood Cemetery drastically different from what we find in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2? Today we share the stories of quarries, infrastructures, and materials that make up New Orleans cemetery stonework. Louisiana Lacks Workable Native Stone The geology of southern Louisiana is similar to that of other states along the Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of mostly sedimentary rock, clay, limestone, and sandstone, Louisiana has few stone resources that would be desirable for cemetery monuments.[1] Furthermore, the stone that is quarried in Louisiana has historically been of poor quality for building. For example, during the 1850s construction of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., requests were made that each state donate a block of native stone to be placed in the interior of the monument. Louisiana sent a block of sandstone that, within the decade, was so crumbling and decayed that it was replaced with a block of Pennsylvania marble.[2] Thus, from the eighteenth century onward, the stone used in New Orleans cemeteries was imported from elsewhere. Various types of slate, marble, and granite were made available as trade routes and quarries opened. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans merchants and dealers offered stone from a number of different places. As time went on, the availability and sources of stone widened.

Arkansas slate was quarried from areas near the towns of Hot Springs, Little Rock, Benton, Malvern, or Mena. This small vein of quality slate, approximately 100 miles long, could produce stone of red, gray, green, or black appearance. Despite the availability of slate from Arkansas, Pennsylvania slate continued to be quarried and shipped to New Orleans. Historic Louisiana newspapers frequently mention the quality and availability of slate from the Bangor quarry in Northampton County. Given the same name as a slate quarry in Wales, the “Old Bangor” quarry had an office in New Orleans by the 1870s. Old Bangor slate is “very dark gray, and to the unaided eye has a fine texture and fine cleavage surface, almost without any luster. The sawn edge shows pyrite.” The Williamstown, Franklin, and Pen Arygl quarries of Pennsylvania also had retail agents in New Orleans, who advertised their slate to be of the same quality as that of Wales.[6]

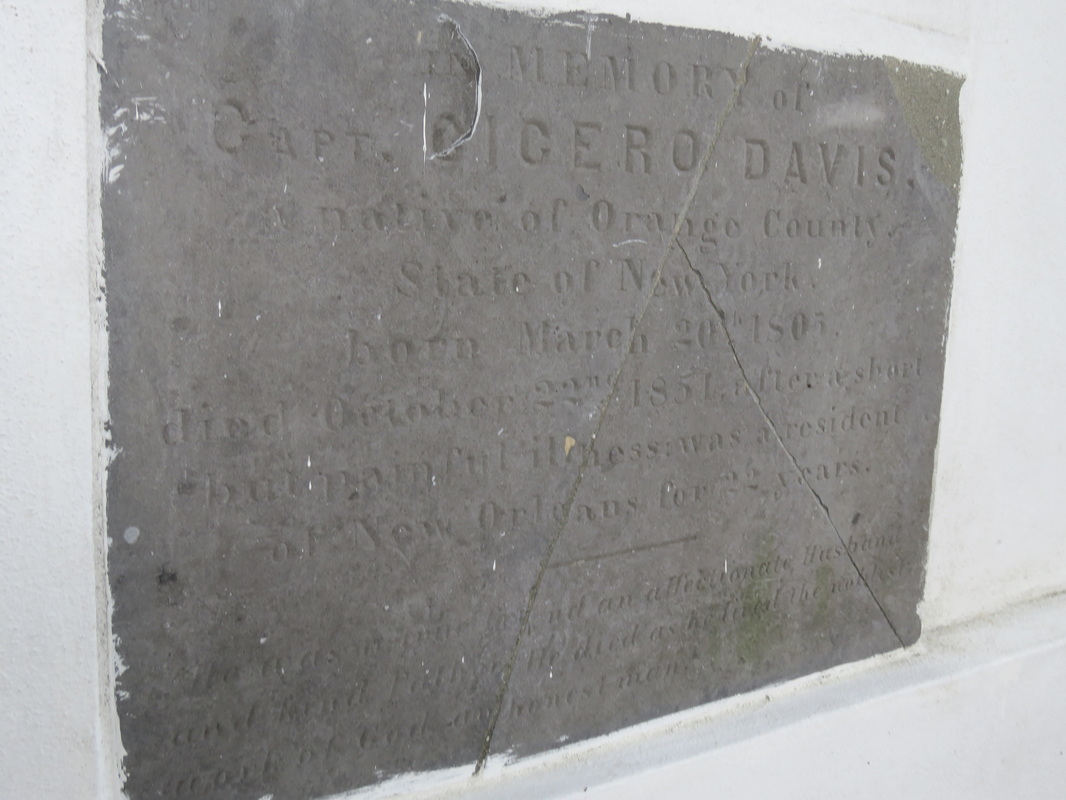

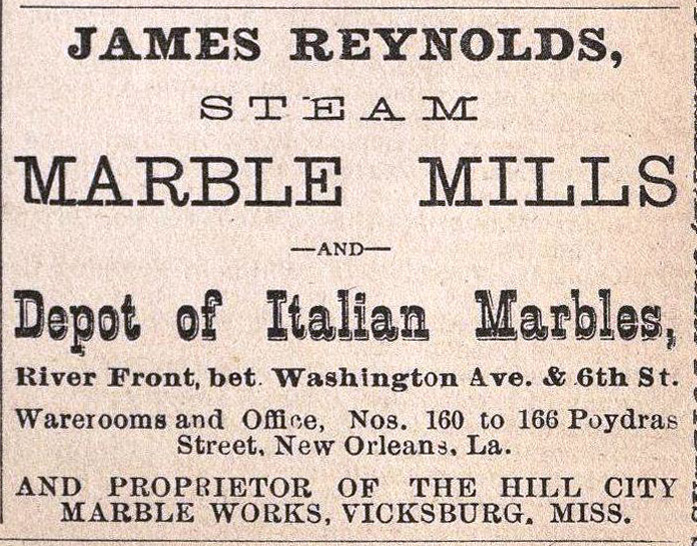

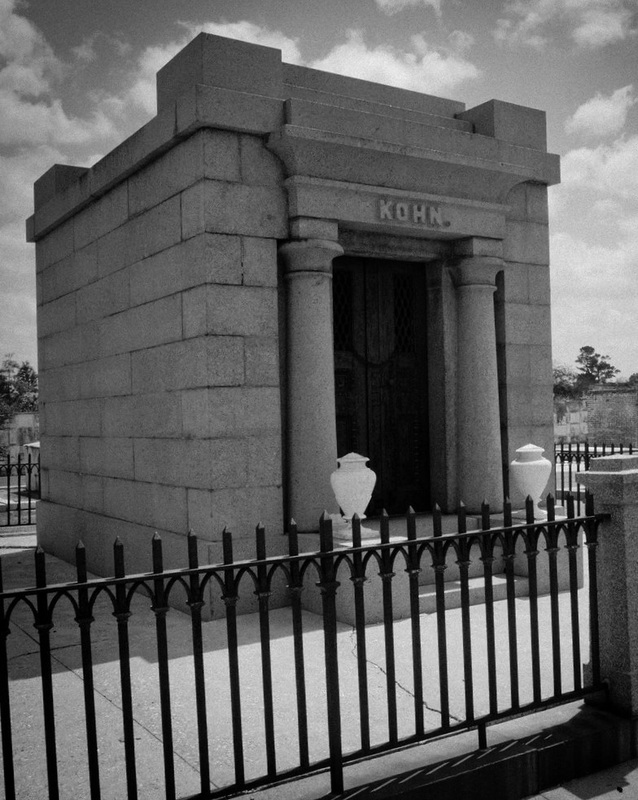

They form by the compression of these sediments, along with all the calcium-rich seashells within. They diverge when these sediments either compress and become sedimentary rock or, alternatively, are subject to higher pressures and become metamorphic. Limestone is sedimentary, marble is metamorphic. Limestone is most prevalent in the oldest remaining New Orleans cemeteries, namely St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, although precious isolated examples are found in other cemeteries. In this context, limestone was used for closure tablets. Limestone closure tablets are usually dark gray (likely quarried in Arkansas or Tennessee) and can be identified by the tiny fossilized shells included in the stone’s matrix. Around the mid-nineteenth century, whiter limestones were used in the same context as marble and are harder to identify. Some rough-faced stones that appear to be marble can be identified as limestone by spotting the shell inclusions within. These rare examples of white limestone were often quarried in Tennessee. Imported Marble: An Italian Commodity New Orleans was a primary hub for the import and export marble from both Europe and the United States. Used for closure tablets, shelves, memorial sculpture, apex sculptures, tomb cladding, and other decorative elements, marble was the medium in which cemetery stonecutters primarily worked throughout the nineteenth century. Based on documentary evidence, the quarries of Italy were the primary source of marble into the 1850s. Italian marble was either directly imported from Italy or arrived via northeastern ports like Boston or New York.[7] Florville Foy, who advertised aggressively throughout his career, frequently promoted his most recent shipment from Carrara or Genoa, cut into one, two, and three inch slabs. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux similarly advertised his Italian marble stock.[8] New Orleans stonecutters dealt in and imported Italian marble through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, stonecutter John Hagan (active 1854 – 1890s) stocked Italian marble “for sale at a small advance on New York prices.” George Stroud (active 1866 – 1899) cut his own Italian marble at Monsseaux’s steam cutting plant. James Reynolds (active 1866 – 1880) not only sold his Italian marble in New Orleans but also in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[9] Italian marble, often vernacularly referred to as “Carrara marble” regardless of its quarry of origin, is a stone of high-grade, consistent quality, and a variety of colors including cream, pure white, and blue. As one Alabama quarry owner conceded in 1909, “Italian marble has long been a standard, not only because the stone is undeniably high grade, but also because the blocks are so uniform in quality that all the slabs or pieces from a block can be used together.”[10] The cost of importing marble in New Orleans varied over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century; at times, it actually cost less to import than marble from Vermont or Tennessee. Protective tariffs helped to stabilize the marble industry during the 1880s and 1890s, but the presence of the famed marble remained a factor among monumental craftsmen into the present. For example, in 1914, before Albert Weiblen purchased his own marble quarry in Georgia, he received a shipment of Italian marble so substantial it took two large derricks to lift the fifteen-ton blocks from the steamship in which it arrived.[11] Domestic Marble: Vermont, Alabama, Georgia, and Others The slow development of infrastructure and quarry technology prevented American quarries from competing with Italian marble in New Orleans until the 1850s. In 1845, one of the first marble quarries opened in Talladega County, Alabama. Five years later, another opened nearby, operated by J.M.N.B. Nix. Using a publicity tactic that would become common among quarry operators in the United States, the New Orleans Daily Picayune announced that “Alabama produces marble equal in fineness – that is, purity or clearness and susceptibility of polish – to any in the world, not excepting the most beautiful Italian, Vermont, or Egyptian.” It was Nix’s quarry that sent Alabama’s contribution to the Washington Monument.[12] Talladega marble can appear white, blue, or cream, and often displays black, green, or grey veins, although it is consistently characterized by the fineness of its grain. Its unpredictability in quality and appearance, however, made it costly to extract.[13] Alabama marble remained a presence among New Orleans cemetery craftsmen well into the twentieth century. One of the most recognizable and imposing monuments within Metairie Cemetery, the ornate sarcophagus of Eugene Lacosst, was crafted by Albert Weiblen from pure white Alabama marble.[14] As always, infrastructure dictated which materials were available in New Orleans at a given time period. In 1851, The Vermont Valley Railroad Company connected towns like Rutland to the greater markets in the East and South.[15] Only two years later, sources in New Orleans commented on the great productivity of the Rutland quarries, remarking that their product had gained “a reputation abroad as well as at home.”[16] Rutland and other Vermont marbles can be white, blue, or black. These quarries also produced pure-white sculpture-grade marble.[17] By 1900, Vermont produced more marble than any other American state, and the Rutland quarry was the highest-yielding quarry. Blocks of Vermont marble were sold for between $1.00 and $3.00 per cubic foot in New Orleans, where agents received shipments and distributed order throughout the South and West.[18] Like Alabama marble, marble quarried in Vermont remained in the stockpiles of New Orleans craftsmen into the mid- and late twentieth century. Vermont not only exported its marble to New Orleans, but its marble cutters as well. One account reflected that the stone cutting yards of New Orleans primarily employed skilled sculptors and polishers from the states of Vermont and Georgia.[19] By 1916, Georgia was second only to Vermont in its production of quarried marble. Although marble quarrying had existed in Georgia long before, it appears to only have gained prevalence in the New Orleans market after the Civil War. By 1888, the Georgia Marble Company in Pickens County claimed to be the largest marble quarry in the world.[20] Georgia marble is typically coarse-grained and appears in blue-gray, black, white, and Creole, which has dramatic sweeping shades of dark gray, black, and white.[21] Ubiquitous Georgia Creole Marble Between 1890 and the 1930s, Georgia Creole marble exploded in the New Orleans cemetery market and made an enormous mark on the landscape. This explosion was the result of expert marketing, improved infrastructure, and enormous supply. Modern monument men during this period utilized Georgia Creole marble in nearly every aspect of their work, from tomb cladding to headstones to vases and urns. The streamlined process of tomb building, now executed in a more “cookie cutter” style than previous generations, allowed many more tombs to be built in a short period of time, and Georgia Creole marble was the medium of choice.

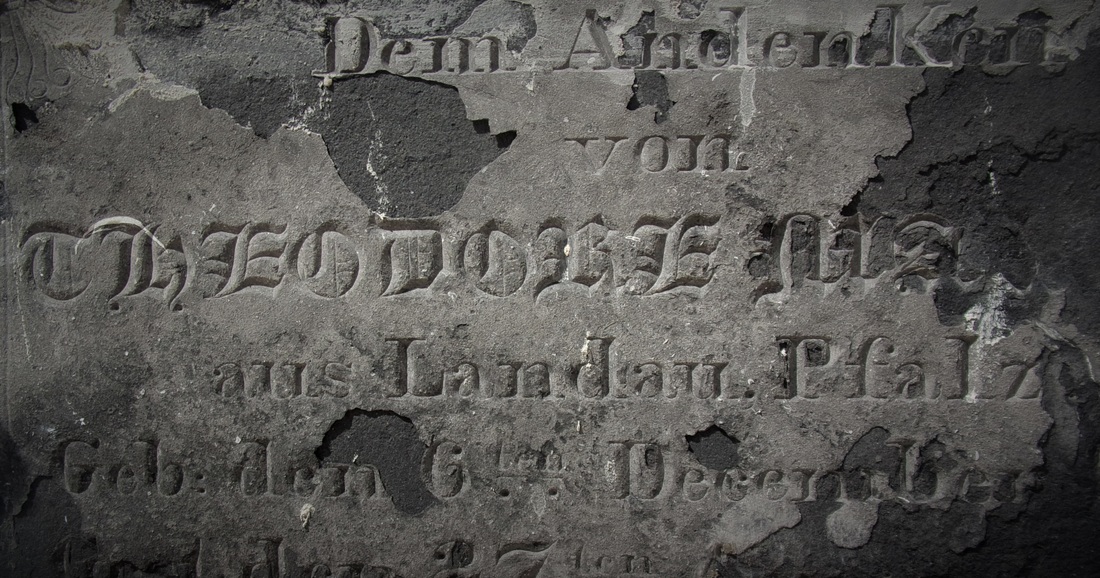

Additionally, as marble is a metamorphosed type of limestone, it is naturally alkaline in quality. Thus, exposure to rain, which is naturally slightly acidic, or any other acidic substance (for example, hydrochloric acid mistakenly intended to clean the stone) will cause marble to granulate and “sugar” over time. An extreme example of marble deterioration can be found in St. Joseph’s Cemetery No. 1. The failure that likely occurred with this stone was related to moisture entrapment within the tomb itself. This, paired with the tight, compressive position of the tablet within the opening, caused the closure tablet to bow and “bubble” outward.

One of the most noticeable granite tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is that of stonecutter and sexton James Hagan. This remarkable tomb was built of red-colored Scotch granite in 1872. Around the same time, Hagan also constructed the monument of Governor Henry Allen, which was also located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 until it was moved to the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the 1880s. This monument, too, was carved from Scotch granite.[24]

[1] Louisiana Geological Survey, Geology and Agriculture: A Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1902), 133-134.

[2] National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Northeast Region, Architectural Preservation Division, The Washington Monument: A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2005), 28. “Washington National Monument,” The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 22, 1850, page 1. The stone is referred to as “freestone,” meaning a soft, friable sedimentary stone. [3] Graham R. Thompson and Jonathan Turk, Introduction to Physical Geology (Rochester, NY: Saunders College Publishers, 1998), 133-137. Slate headstones are found commonly in the Northeast dating to the colonial period. Slate headstones are also present in cemeteries as far south as Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. However, no slate headstones are visible in the cemetery landscapes of New Orleans. [4] Mary Louise Christovich, Roulhac Toledano, and Betsy Swanson, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. I: The American Sector (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 1998), 57. [5] Daily Picayune, September 27, 1850, 2; Daily Picayune, May 2, 1853, 1; Daily Picayune, February 28, 1869, 11. [6] “Alexander Hill, Welsh and American Slates, Slabs, etc.” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 4, 1875, 6. These slates priced from $6.50 to $10 per square; “Slates! Slates! Slates!” Ouachita Telegraph (Monroe, LA), July 22, 1872, 2. [7] “Brig Casket arrives from New York with sundry marble slabs,” Louisiana Advertiser, April 29, 1820, 3. “Barelli & Company, commission merchants, selling blocks of Italian marble,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1845, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 10, 1848, 7; Daily Picayune, February 17, 1848, 3; Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1851 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1851), page AT. [9] Edwards’ Annual Director to the Inhabitants, Institutions….etc., etc., in the City of New Orleans for 1871 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1870), 275; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [10] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. [11] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8. [12] “Alabama Marble,” Daily Picayune, October 1, 1845, page 2; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [13] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. In this year, cost to transport Alabama marble to New Orleans was 32 cents per cubic foot. [14] Leonard V. Huber et. al. New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 54-55. [15] Vermont Railroad Commissioner, Eleventh Biennial Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of Vermont (St. Albans, VT: St. Albans Messenger Co., 1908), 308. [16] Daily Picayune, July 15, 1853, page1; Daily Picayune, June 16, 1855, 1. [17] Thomas Nelson Dale, The Commercial Marbles of Western Vermont (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 117-122. [18] Tariff Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means, Second Session, Fifty-Fourth Congress, 1896-97, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 275-279; “Random Notes,” The Reporter: The First and Only Journal Published in the World Devoted Exclusively to Granite and Marble, No. 1 (January, 1900): 33. [19] David Spence Hill, Industry and Education: Part Two of a Vocational Survey for Isaac Delgado Central Trades School (New Orleans: The Commission Council, 1916), 227. [20] “Science and Industry,” The Colfax Chronicle (Colfax, LA), November 3, 1888, 3. This was not an uncommon claim for many quarries to make. “Georgia Quarries,” The True Democrat (Bayou Sara, LA), January 30, 1897, 7. [21] Memoirs of Georgia, Vol. I (Atlanta: The Southern Historical Association, 1895), 211-217. [22] A. Oakley Hall, “Cities of the Dead,” in Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers Tales and Literary Journeys, Frank de Caro, editor. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998), 532-533; Arthur Wellington Brayley, History of the Granite Industry of New England, Volume I (Boston: National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913), 114. [23] Ibid., 84. [24] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley of Durham University, UK, for his knowledge and expertise in identifying the Hagan tomb as Scottish granite. [25] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1895), 1095. [26] “Notes from the Quarries,” Stone: an Illustrated Magazine Vol. 4 (1892): 496. As any narrative on de Pouilly does, this article relies on the groundbreaking research and thesis of Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University thesis, 1992. Which exquisitely analyzed de Pouilly’s work in New Orleans cemeteries. One hundred and forty years ago, on February 21, 1875, Jacques Nicholas Bussiere de Pouilly died in his home on St. Ann Street. In his seventy years of life, de Pouilly had been the harbinger of European neoclassical and revival architecture in New Orleans. We see his touch on our city streets – in St. Augustine Catholic Church, and most notably St. Louis Cathedral. But his influence was arguably greatest in the city’s cemeteries. De Pouilly’s work is present in nearly every viewpoint of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, and much of Cypress Grove Cemetery. The breadth and innovation of his tomb architecture generated uncountable replications and inspirations, the products of which have shaped our burial grounds. J.N.B. de Pouilly was born in July 1804 in Châtel-Censoir, France, southeast of Paris. While much of his early life is unclear, it is assumed that in his architectural training he was influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, if not a student of the school himself.[1] He arrived in New Orleans in 1833, a time in which the French-speaking population of the city hungered for reconnection with Continental styles. He quickly became the architect of note for the city’s First District, designing the St. Louis Exchange Hotel, among many other residential, commercial, and religious projects.

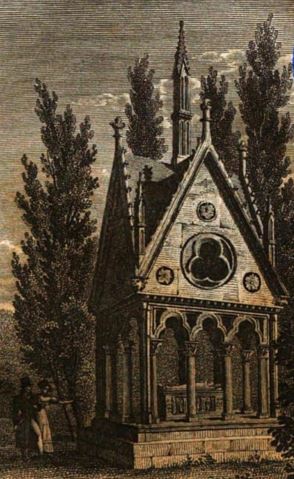

While Père Lachaise and Creole cemeteries like St. Louis may appear stylistically similar, de Pouilly had the significant task of fundamentally shifting the function of his New Orleans tombs from their Parisian prototype. Although the monuments of Père Lachaise appear to be tombs or mausoleums, their design accommodates instead for below-ground burial. That the architect’s designs kept their Parisian aesthetic while having been fundamentally re-worked to allow for above-ground burial is among the more impressive of his professional achievements.[3]

In addition to the French St. Louis Cemeteries, de Pouilly worked also in American-dominated Cypress Grove Cemetery (est. 1840). In Cypress Grove, de Pouilly additionally contracted with granite magnate Newton Richards to build the memorial of fallen firefighter Irad Ferry (died 1837). He relied, too, on Monsseaux and Foy to construct such masterpieces as the Maunsel White tomb. De Pouilly clearly had a strong grasp on the value of trade and materials, based on his choice of craftsmen and his apparent innovations in the world of cast stone. De Pouilly’s career was marred by two construction disasters in the 1850s – first, the collapse of the central tower of St. Louis Cathedral while de Poilly was head architect, and second the collapse of a balcony at the Orleans Theatre. From this point onward, his rising star waned, but it appears never to have faded in New Orleans cemeteries. In 1874, de Pouilly composed the final drawing in his only surviving sketchbook – a tomb he designed for himself and his family. This tomb, like many depicted in his prolific sketches, would never be constructed. Instead, de Pouilly was interred in a family wall vault in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Although the location was surely not intentional, the wall provides a lovely view of a number of de Pouilly-designed tombs. In a nearly-illegible detail to his memorial tablet, the signature of Florville Foy can be detected as the carving hand of de Pouilly's final tablet. De Pouilly’s obituary on February 22nd spoke grandly of a man who lived honestly and in service of his profession:

St. Peter’s lofty dome cenotaphs the name of Michael Angelo [sic]: Sir Christopher Wren’s greatness is sepulchred in the mightiness of St. Paul’s. Mr. De Pouilly fashioned no wonders such as these, but yet a greater, the enduring fabric of an honest life, and will be entombed in the constant remembrance of devoted friends. After a painful and lingering illness, Mr. De Pouilly, hoary with the winters of seventy years, and surrounded by children and other relatives, bade farewell to things of earth. This sad event occurred yesterday, Sunday, 21st.[4] The Daily Picayune made no note of the many cenotaphs de Pouilly himself had helped write, in the tablets and along the aisles of our cemeteries. But if 140 years is a sufficient measure of the timelessness and impact of one’s work, his name certainly engraved upon many more memorials than just his own. Below is a gallery of only a portion of de Pouilly’s work, and a few tombs inspired by his designs. Photos by Emily Ford unless otherwise noted. [1] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” 5-7.

[2] Peggy McDowell and Richard E. Meyer, The Revival Styles in American Mortuary Art (Popular Press, 1994), 59. [3] Masson, 30-35. [4] “In Memoriam – J.N. de Pouilly,” Daily Picayune, February 22, 1875, 2. At the end of the main aisle in Square 1 of St. Louis No. 2 is a simple tomb with a low-pitched gable roof. Coated in modern cement and latex paint, it is difficult to determine much about its original appearance. Perhaps it was once coated in brightly-colored stucco, or its roof tiled in slate or terra cotta. Ironwork may once have enclosed its simple design. Without the fortunate discovery of an historic photograph, which is extremely rare, the elegant past of this tomb may never be known. But the de Armas tomb offers a hint to the scrutinizing eye. Its marble closure tablet is embellished with an ornate relief carving depicting a winged hourglass encircled with a floral wreath. The hourglass is surrounded by a snake eating its tail – the ouroboros – a symbol of immortality. Among the few depictions of the winged hourglass in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, this carving is by far the most detailed. Such a carving is indicative of a level of style and craftsmanship long faded from New Orleans cemeteries. At one time it was not alone in its ornamental beauty, but instead belonged to a rich landscape of beaded wreaths, draped urns, and weeping angels. Even today, the de Armas tomb is not alone in one regard. Nearly three miles away, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2’s younger sister, St. Louis No. 3, stretches along the edge of Bayou St. John in long aisles. Amidst its large lots and photogenic tombs is the tomb of the Depaquier family. Uncompromised by modern repairs, the faded stucco walls bely that the tomb was once limewashed a dark rose color. The pitch of its roof is reminiscent of the de Armas tomb. The closure tablet of Dupaquier tomb is bordered with a carved braided rope. Atop its simply-lettered epitaph is a winged hourglass nearly identical to that found on the de Armas tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Studies of cemetery craftsmanship in New Orleans have shown that few motifs, materials, or methods in cemetery stonecarving are the result of happenstance. Who carved these tablets? What do they symbolize? And why did the Dupaquier and de Armas families end up owning identical tablets? The de Armas and Dupaquier Families The two tombs are the burial places of the patriarchs of their respective families. In St. Louis No. 2, Michel Theodore de Armas (sometimes listed in documents as Michael or Miguel), was a notary and lawyer who was born in New Orleans in 1783 and died in 1823.[1] In St. Louis No. 3, Claude Dupaquier was born in France in 1806, arrived in New Orleans in the 1840s, and died in 1856.[2] Between 1823 and 1856, life expectancy was around 37 years, so that these men died at age 40 and 50 (respectively) is unremarkable. Both de Armas and Dupaquier had children that became important members of New Orleans’ business and social circles after the Civil War. Dr. Auguste Dupaquier, who is buried with his parents, was described as having a “gentle, loving, and kindly temperament, mixed with firmness and rare energy, and he secured the affections of all whom he approached.[3]” Dr. Dupaquier had no discernable interaction with the children of de Armas, and it is unlikely that the families had enough relation to construct matching tombs knowingly. One significant similarity between the Michel de Armas and Claude Dupaqueir was their preference for the French language. Both tablets are carved in French.

In nineteenth century New Orleans, a person’s linguistic and cultural identity often determined who they chose to carve their final epitaph or build their eternal resting place. For de Armas, or his widow, Gertrude St. Cyr Debreuil, it would have been a given that they chose Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. New Orleans cemeteries are populated with the small, often overlooked signatures of local stonecutters. Often these signatures wear away, and craftsmen often neglected to sign their work at all. Many stonecutters began their careers working for other more established cutters, signing the name of their master instead of that of the apprentice. These realities complicate the study of cemetery craftwork. In the case of the de Armas closure tablet, a small, clean-lettered signature is present at its bottom right-hand corner – MONSSEAUX. The Depaquier tomb retains no signature at all. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux Like Claude Depaquier, Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux (1809-1874) was a French native who arrived in New Orleans as an adult.[4] Present in New Orleans by 1842, Monsseaux is best known as the stonecutter who built many tombs designed by architect J.N.B. De Pouilly. These included many famous tombs in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Monsseaux often worked with other stonecutters in either a master/apprentice role or as business partners. In addition to his work for J.N.B. de Pouilly, his signature is often found beside other cutters like Tronchard and Kursheedt & Bienvenu. Through his entire career, Monsseaux held the same marble yard on St. Louis Street at the corner of Robertson Street – directly beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 and New Basin Canal. Through his career, Monsseaux also sold marble to fellow stonecutters; he partnered with others to secure equipment and technology that advanced the trade. Most notably, he owned a steam marble works for some time in the 1870s, the rights to which he lent to other cutters Stroud and Richards.[5] Monsseaux’s accomplishments were many, but his clientele was rather distinct. Most of Monsseaux’s signed tablets are carved in French. In this manner, Monsseaux is a French counterpart for German-speaking stonecutters of the time who served a distinctly German clientele. There are always exceptions – Monsseaux built the DePouilly-designed Iberian Society tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Yet the majority of his work served French-speaking clients who belonged to the upper echelons of New Orleans society. Stylistic Inspirations and Symbolism French speaking upper-class New Orleaneans in the 1830s were enthralled with the style and beauty of tombs found in Paris’ Pere Lachaise Cemetery at the time, and Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux gladly catered to that demand. Sarcophagus-style tombs with corner acroteria and inverted torches appeared in St. Louis No. 2 during this time. These tastes adapted through the 1850s and into the first years of St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. Greek Revival temples and Egyptian Revival tombs rose in the squares of the both cemeteries, mimicking the aisles of the great French burial ground. Often, it was Monsseaux who provided his clients with these romantic sepulchers. Pere Lachaise Cemetery is populated with hundreds of winged hourglasses. In fact, the first image to greet the visitor at the cemetery gate is a pair of such hourglasses. This is also the case at Montparnasse Cemetery, also in Paris. The history of the winged hourglass as a funerary symbol appears to split along linguistic and cultural lines in the United States. In the English-speaking Northeast, it is contemporary with the skull-and-crossbones and death’s head, symbolizing the fleetingness of time. In this context, the winged hourglass was contemporary to the 18th century and faded from popularity by the 1830s. French-speaking New Orleans funerary culture developed more closely to that of Paris than its American cousins, however. The winged hourglass is seldom seen in tombs constructed prior to 1820. It does, however, appear to grow in popularity from 1820 through the 1850s, when the de Armas and Dupaquier tombs were constructed. This inspiration was drawn directly from the Parisian cemeteries. And New Orleans was not alone in this inspiration. Not to be outdone as a European city in the New World, Buenos Aires’ Recoleta Cemetery, founded in 1822, hums with the flutter of winged hourglasses. The de Armas and Dupaquier families may never have known each other, but they are together twin scions of a lost cemetery landscape. Opulent with their floral wreaths and outspread wings, their hourglass tablets were likely carved by Monsseaux himself or an apprentice. It is possible, even, that the Dupaquier tablet was a replica of de Armas’, carved by a student still learning his trade. Or, perhaps, both designs were borrowed from a pattern book imported from Paris. In any case, they endure as silent reminders of the importance of each tomb in the larger landscape of our historic cemeteries. [1] Florence M. Jumonville, Ph.D., ‘Formerly the Property of a Lawyer’: Books that Shaped Louisiana Law. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Library Facility Publications, 2009, 7.

[2] Orleans Death Indices 1804-1876. Vol. 17, 312. [3] “Death of Dr. Dupaquier,” New Orleans Daily Democrat, April 8, 1879, p. 8. [4] Charles LeJ. Mackie, “Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux: Marble Dealer,” printed in SOCGram, Fall 1984, 14-16. [5] Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. The third in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. 23,707 infected. Not less than 4,600 dead. Such was the toll of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in New Orleans. The Crescent City was ground zero – the first point of contact in the United States for an epidemic that swelled north and eastward from July through November, taking 20,000 souls in total. Dozens of burials in each cemetery each day led one report to state that, in a sense, each day of the summer of 1878 had been All Saints’ Day. On the day of the holiday itself, many graves still retained the decorations of burial.[1] And the epidemic was not even completely over.

In the days leading up to All Saints’ Day, some health officials even cautioned against the yearly tradition of decorating and caring for loved ones’ graves. Said the Daily Picayune: It should be mentioned… that some physicians are of the opinion that, owing to the extraordinary number of interments during the summer and the prevalence of infectious disease, it would not be safe for a general decking of graves to be carried out as on occasions of the past.[2] |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly