|

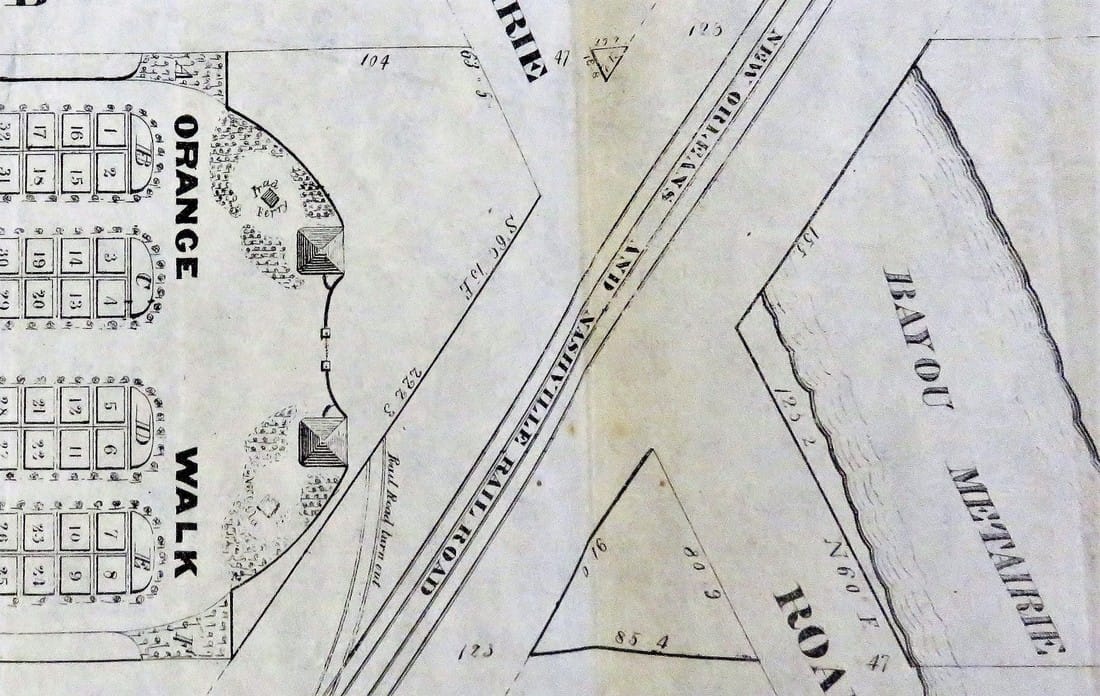

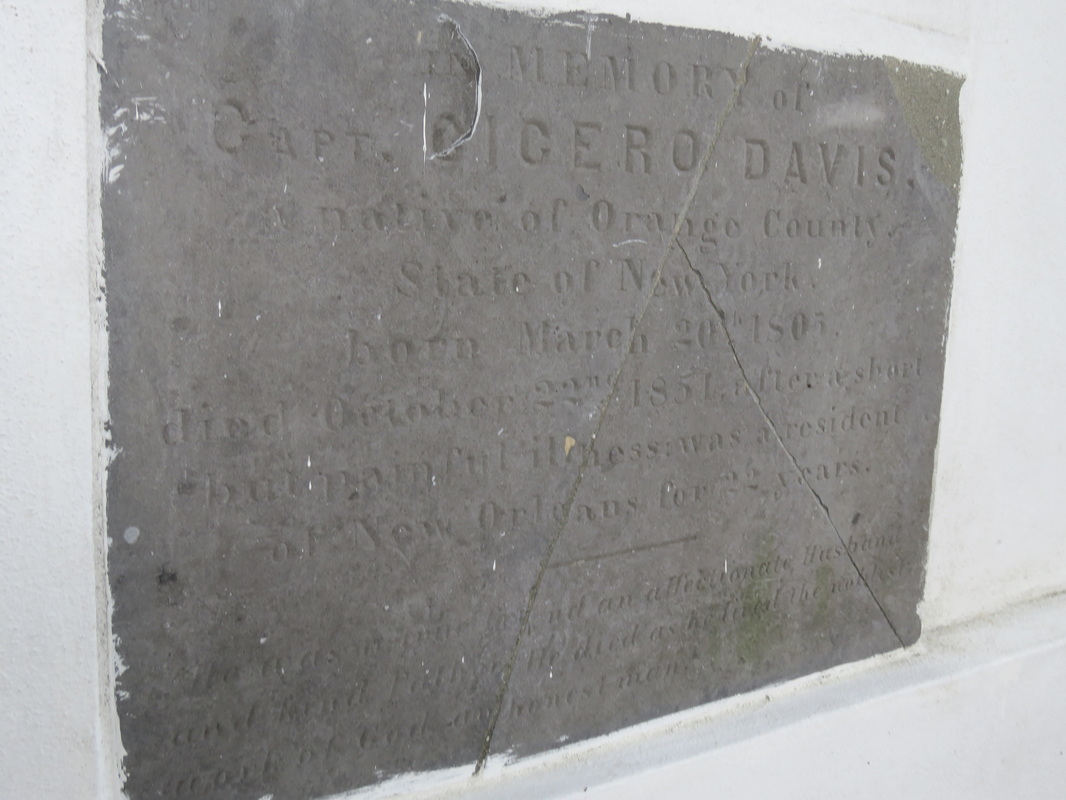

Part Two of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. Find Part One here. In the 1840s, Cypress Grove Cemetery developed into the landscape its founders envisioned: tree-lined and populated with tombs of the finest order. It also gained company as St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest were all established between 1840 and 1850. There at the corner at what is now Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Cypress Grove was part of a pastoral scene: barges floating up Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal, visitors strolling the gardens at the Halfway House, and rail cars pulling up right to the cemetery gates, unloading mourners and the bodies of the mourned.[1] Between its founding in 1840 and the turn of the century, Cypress Grove would become the final resting place of many famous and infamous New Orleans characters. Northern-born transplants to the city would combine New Orleans tomb architecture with the styles and materials they were accustomed to. Firemen would memorialize their fallen brethren within the cemetery’s marble-clad walls. Much of the incremental detail of the cemetery at its height, though, has weathered away from its present-day appearance. It’s easy to miss this historic garden cemetery for its modern lack of trees. But with historic research and a keen eye, it’s possible to rediscover Cypress Grove’s historic grandeur. Firemen, Northerners, and Protestants Cypress Grove was the first fraternal cemetery in New Orleans. All other cemeteries founded up to 1840 belonged either to the Catholic parishes (except Protestant Girod Cemetery, belonging to Christ Church Cathedral) or to each respective municipality (i.e. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1). Many other fraternal organizations, including other firemen’s organizations, would found their own cemeteries over the course of the nineteenth century. Cypress Grove was not intended for the exclusive burial of firemen. It served all New Orleanians seeking burial, if they could purchase a plot, and many who could not. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (present-day Canal Boulevard) was contracted by the City of New Orleans for indigent burial, even after Charity Hospital Cemetery was established in 1848.[2] While Catholics in New Orleans had many cemeteries from which to choose, Protestants had only Girod Street Cemetery and the municipal cemeteries. Perhaps it was simple economics that caused so many Northern-born Protestants to buy property in Cypress Grove. It may also have been caused by cultural interaction between the Firemen (many of whom were also non-native New Orleanians) and others who joined them as newcomers in the Crescent City. In any case, the great majority of historic burials in Cypress Grove denote birth in northern climes such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and others. The Firemen’s Charitable Association fell into this market easily. Stonecutters whose work featured mostly in Girod Street Cemetery, such as long-time Girod Street sexton Horace Gateley, executed tombs and tablets in Cypress Grove as well. Gately himself, who drowned in at Isla del Padre, Texas in 1867, is buried in adjoining Greenwood Cemetery. The FCA even advertised in-ground burial in Cypress Grove. While in-ground burial occurred in nearly every cemetery in the city, FCA was the only cemetery owning body to advertise it – plainly appealing to newcomers with a distaste for Continental-inspired above-ground tombs.[3] When Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957, Cypress Grove became a de facto artifact of what the Protestant cemetery may have looked like. Simpler, sarcophagus-style tombs with accents placed more on great obelisks and sculpture than on Greek acroteria or Baroque scrollwork dotted the aisles of both Girod and Cypress Grove. What few photos of Girod Street Cemetery remain even suggest a few duplicate tombs between both cemeteries: including the now headless and armless tomb statue and tomb of Henrietta Sidle Davidson (died 1881) and another tomb in Girod Street. Philadelphia brick, New Hampshire granite, and other Anglo-inspired tastes contributed to the budding landscape of Cypress Grove.

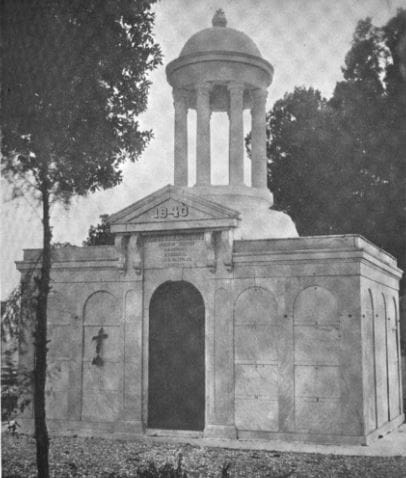

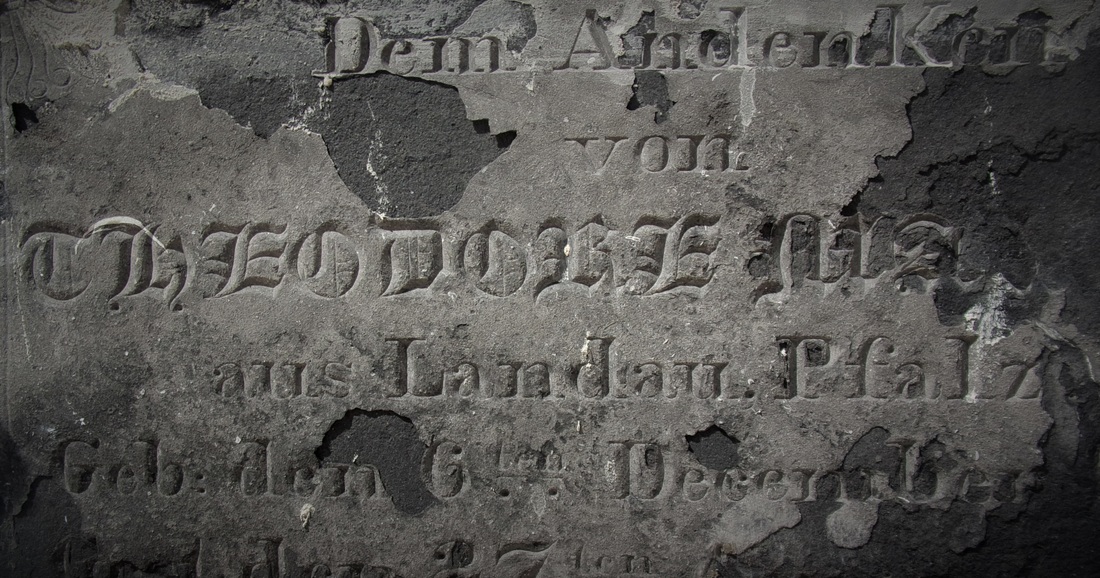

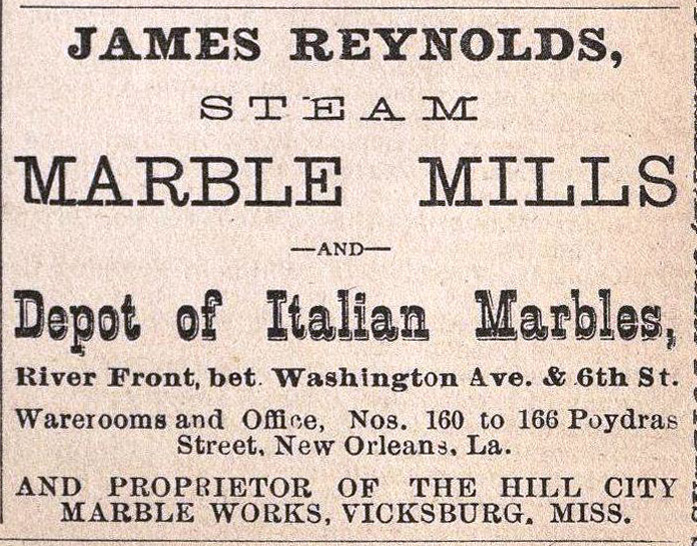

Mr. [S.T.] Jones placed a closely sealed bottle in the box, containing the constitution and list of members of this efflisient [sic] company, the daily newspapers of the city, and the various coins of the country. This was also embedded in mortar, the cover put on, and the whole covered with solid masonry, upon which the corner stone was laid. The beauty of the day, the solemnity of the occasion, and the mournful memories engendered by the scenes around, all contributed to give the ceremony a peculiar interest.[5] The tomb of Perseverance Lodge No. 13 dominated the entrance of Cypress Grove Cemetery then as it does now – a large terra cotta cupola with ionic columns and a cast-iron finial at its dome was constructed atop the tomb roof. At the center of its primary façade, an entrance was likely constructed which was enclosed by cast-iron doors. Above this door were marble brackets and a Classical pediment. The tombs of Philadelphia Fire Engine and Eagle Fire Company were tucked into the front corners of the cemetery. Each built identically, with marble-clad masonry and large urns and finials, they were each enclosed with iron gates, each within the line-of-sight of the Irad Ferry monument. Masterpieces in Marble and Granite Other societies in addition to fire companies would build their tombs in Cypress Grove, most notably the Chinese tomb and Baker’s Benevolent Association tomb. But Cypress Grove would make its mark in the number of great family tombs that populated its aisles. The sarcophagus tomb is one of the most notable artifacts of funerary architecture in New Orleans cemeteries, and in Cypress Grove this was no different. Built of brick and clad in marble pilasters, cornicework, and sculptural elements, the sarcophagus tombs of the McIlhenny, Davidson, Johnston and Walker tombs are examples of the dozens of this burial type found in Cypress Grove. Built by stonecutters like Anthony Barret, James Reynolds, and Newton Richards, they represented the English-speaking stonecutter’s take on a burial style often associated with Creole artisans. The French-speakers were present in Cypress Grove, as well. Sarcophagus tombs by signed by Florville Foy are present beside the work of New Orleans-born Jewish stonecutter Edwin I. Kursheedt. Renowned French-born cemetery architect J.N.B. de Pouilly designed two of the best-known tombs in Cypress Grove: those of Maunsel White and Irad Ferry (constructed by Monsseaux and Richards, respectively).

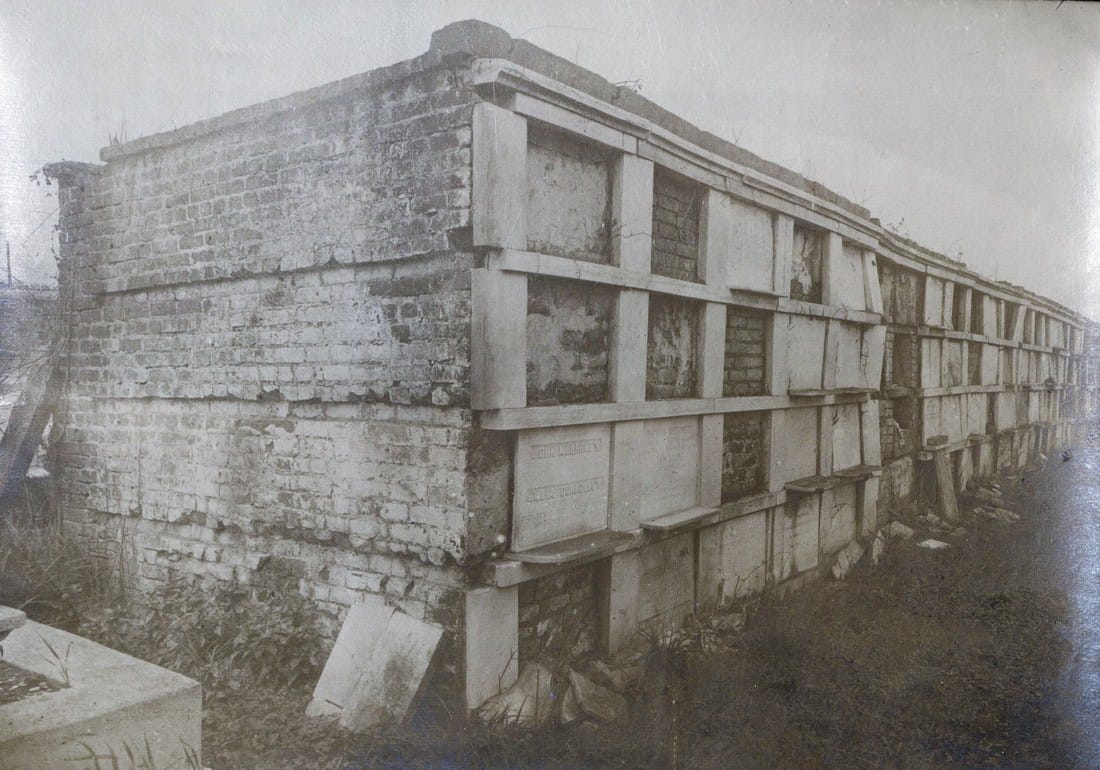

The only remaining example of this style of historic tomb construction lies not in Cypress Grove but in Metairie Cemetery – the Duverje family tomb, constructed between 1808 and 1820 and moved from the family cemetery in Algiers in 1916, retains such acroteria. They are the last of their kind in New Orleans cemeteries. Then and Now After 1945, New Orleans cemeteries underwent a seismic shift in management, industry, and trade. The monument industry had been slowly becoming a national affair managed by large companies – a shift that reached New Orleans after World War II. Over the years, most cemeteries abandoned the employ of the cemetery sexton who traditionally cared for the grounds on a daily basis. Stonecutters, who had often served as sextons, adapted and became cemetery owners and dealers of nationalized products. Technology changed the way tombs were built, repaired, and maintained. This shift affected every cemetery in New Orleans. In the Catholic cemeteries, it led to the consolidation of parish burial grounds into the incorporated New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. In municipal cemeteries, it meant a transfer of management to overstretched city departments that cared for publicly-owned buildings and parks.[7] In the fraternal cemeteries, it meant a consolidation of duties and a new focus on sellable space to accommodate budget shortfalls.[8] With population movement to the suburbs and elsewhere, tombs were less likely to be cared for by their owners. With no sexton to manage the landscape, small issues with tombs became larger problems, often solved in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Storms like Camille, Betsy, and Katrina flooded Cypress Grove Cemetery, killing many of the surviving trees. Those who entered the monument trade after 1950 were much more familiar with new technologies than old materials. Old problems, then, were solved in new ways. In the 1960s, when the marble facing of the extensive wall vaults at Cypress Grove began to sag away from their brick substrate, the decision was made to remove the marble instead of repair it. When landscaping tumuli was too labor intensive, the sod was stripped from their structures, leaving cement-patched, igloo-like bodies behind. Herbicides like RoundUp were selected to replace arduous mowing, damaging masonry and causing grassy root structures to erode, leaving deep ruts which can destabilize walls and tombs. Alternately, trees which lent such a rural feel to Cypress Grove eventually overgrew their root structures, tipping walls and capsizing tombs. All the while, the responsibility of families to care for and repair their own cemetery property became anachronistic in an era of new innovations and perpetual care. The cultural forces that created Cypress Grove had transformed, with the role of the fraternal society somewhat supplanted by the rise of Social Security and insurance companies; the rural cemetery now firmly at the edges of the metropolis. New Orleans cemeteries in general are prized for their historic value, but the value of their maintenance and preservation may exceed that interest from many sides. Yet Cypress Grove remains, its Egyptian columns rising above Canal Street and City Park, where once the bayou and the railroad met. It may be difficult to see it, but with a conscientious eye and a little history, its lost landscapes can be found. [1] “Passenger and Freight Barges on the New Canal,” Daily Picayune, January 1, 1846, 4; Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louis Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Press, 2004), 30-35; At least one duel also took place in front of Cypress Grove’s gates, between former state senator Waggaman and a former New Orleans mayor Prieur, Daily Picayune, March 11, 1843, 2.

[2] Daily Picayune, April 21, 1846, 2. [3] “Cypress Grove Cemetery,” Daily Picayune, September 15, 1842, 2. Full text: “CYPRESS GROVE CEMETERY. A portion of this rural cemetery having been appropriated for interments in GRAVES, application can be made at the Firemen’s Insurance Office; to M.C. Quirk & Sons, or Mr. Monroe, Undertakers. The Superintendent will also receive at the ground any corpse for interment, on payment of $5 for grown persons and $3 for children. GEORGE BEDFORD, President F.C.A.” [4] “Grand Fancy Dress Ball,” Daily Picayune, February 26, 1852, 3; “Fireman’s Funeral,” Daily Picayune, August 14, 1847, 2. [5] “The City: An Interesting Ceremony,” Daily Picayune, January 3, 1854, 1. [6] Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1855 (New Orleans: Printed at the office of the Picayune, 66 Camp Street, 1855), xiv. [7] Pie Dufour, “Old Cemetery Getting New Look,” Times-Picayune, November 10, 1968. [8] In Cypress Grove, sexton and stonecutter Leonard Gately was instrumental in developing sections into sellable space. Daily Picayune, April 12, 1959, 154.

3 Comments

To call any cemetery landscape “eclectic” is usually an understatement. Within cemetery landscapes are the architectural whims of uncountable individuals, families, and craftsmen. And so it goes that in New Orleans cemeteries we pass a Gothic chapel and find a Celtic cross. Our landscapes are amalgams of recollection – Classical Greek, Roman, and Egyptian are at home with the Italianate, the Moorish Revival, and the Art Nouveau. This rich tradition has inspired architects to look backward for inspiration, but there is no farther backward one can reach than the tumulus. Known also as a barrow, the tumulus is a burial structure that rises from the ground as a hill or mound. Often, the tumulus bears a means of access from the side or top of the hill. Its origins span across the ancient world, both Old and New, representing a common type of burial shared between the ancient Norse, Etruscans, Chinese, Native Americans, and many, many more.[1] This type of burial also has its home in New Orleans cemeteries. The Elks Lodge tumulus in Greenwood Cemetery, and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia in Metairie Cemetery are often used as examples for the tumulus in modern cemeteries. Yet they are not alone in their unique appearance. The tumulus once graced many more New Orleans cemetery landscapes than it does today. In this blog post, we explore the origins, proliferation, and eventual disappearance of the tumulus in New Orleans cemeteries. Mounds, Barrows, and Antiquarians In Europe, mound, barrow, or tumulus burial was practiced by pre-Roman and Roman cultures. Tumuli can be found in nearly every European country – today as protected archaeological sites and heritage attractions.[2] The practice of mound burial was abandoned after the rise of Christianity and the development of churchyards in Europe. Until the cemetery landscape was reinvented by the rural cemetery movement in the early 19th century, the tumulus was a thing of ancient history. A number of factors contributed to the reintroduction of the tumulus to cemetery landscapes in Europe and the New World. With the establishment of cemeteries like Pere Lachaise in Paris, the understanding of cemetery landscapes shifted into one of green space and architectural eclecticism. From this cultural development sprang the Greek Revival architecture that proliferated New Orleans thanks in part to J.N.B. de Pouilly. But the gaze of nineteenth century Europeans and Americans did not exclusively look back to Greece. It turned to Egypt and the Middle East. It incorporated Gothic spires into new designs. And it looked even farther back to the mysterious mounds found in the European countryside. By the 1870s, the antiquaries of Europe excavated numerous tumuli in England, Italy, France, and Norway. Such discoveries were commonly featured in New Orleans newspapers.[3] An awareness of the burial mounds of great ancient cultures joined Greek temples and Gothic cathedrals in the consciousness of New Orleaneans. Furthermore, the people of the American South were familiar with mound burial in their own backyards. The presence of seemingly abandoned mounds in the southern and mid-western United States had captured the interest of Europeans since Hernando de Soto reported their existence in 1541. After colonization and into the nineteenth century, some of these mounds in Louisiana were repurposed by Americans for use as their own cemeteries. This was the case in Monroe’s Filhiol-Watkins Cemetery. Fleming Plantation Cemetery is also located on a Native American mound. By the mid-nineteenth century, mound burial was firmly rooted in the imagination of New Orleaneans. From these inspirations, the tumulus made its debut in cemetery landscapes. The Tumulus in New Orleans Like the city itself, New Orleans cemeteries are the product of many layers of community and identity. Each cemetery is a reflection of the people who made it their own. Cemeteries that were built and utilized by Irish, German, or American New Orleaneans developed with a different aesthetic than those shaped by French speakers. Each community drew upon their own culture and style to create their cemetery. The tumulus entered the popular consciousness in part via a new interest in archaeology and ancient architecture.[4] Though tumuli in New Orleans often had Greek Revival motifs, they were utilized by Americans elsewhere in the United States. Great northern cemeteries like Mount Auburn featured tumuli as part of their cultivated agrarian landscapes, as did closer cemeteries in Charleston and Savannah.[5] Thus, it is no surprise that tumuli in New Orleans appeared first in American and not Francophone cemeteries – decades before the Elks, the Army of Tennessee, or the Army of Northern Virginia. Tumuli are found primarily in the Canal Street cemeteries, including Cypress Grove, Masonic, Odd Fellows Rest, and Greenwood. They are also found in American-oriented cemeteries like Lafayette Cemeteries No. 1 and 2. There are dozens of tumuli to be found in our cemeteries, yet the untrained eye will not find one. Hidden Tumuli, or How the Lawnmower Changed Everything Most tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries no longer look like tumuli. Stripped of their grassy hill features, they appear instead simply as unusual tombs with rounded bodies. The Hornor and Holdsworth tumuli in Cypress Grove and Masonic Cemeteries (respectively) are good examples. Both constructed with a marble primary façade featuring relief carvings of cut flowers, they were likely carved by the same craftsperson, although neither structure is signed. Both tumuli have conspicuously rounded structures that seem to contrast with the grandiose style of their primary face. Yet when imagined as they originally appeared, as green hills from which their marble faces projected, their aesthetic comes together. There are many former tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries that have been stripped of their signature mounds. The John P. Richardson tomb, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, was described in 1885 as “enclosed in a tall oval mound of turf, with marble doors set in a stone frame.”[6] The tumulus memorialized Richardson’s young daughters – Ella and Marguerite Callaway or “Calla,” ages six months and four years old. This original appearance could certainly not be deduced from examining the Richardson tomb today: its sweeping marble doors and arched primary face are attached to what appears to simply be a brick-and-mortar tomb. Dozens of former tumuli can be found in New Orleans cemeteries; most are identified by the slightly unusual appearance of the tomb body when compared to its front. Nineteenth century tumuli were designed to appear monumental in both mass and detail, with their entrances featuring sweeping side elements or rounded tops. The massive hill that comprised the tumulus body framed these features. Other examples of former tumuli include:  McIntosh tumulus, Cypress Grove Cemetery. In November 1873, the Nixon (now McIntosh) tomb was described as: "in the form of a mound overgrown with grass, with a large marble front. Along the top of the slab creeps an ivy, which will eventually cover the whole mound. The frontispiece was garnished on each side by a vase of white flowers." (New Orleans Republican) The disappearance of historic tumuli can be explained in the same way many other landscape features have been altered. As cemetery design, economics, and management changed, the tumulus was viewed as far too costly to maintain. Before the 1920s, cemeteries featured cultivated grounds with aisles paved in crushed shells – and they were manicured using manual, spiral-bladed lawn-cutters. Between 1920 and 1945, new lawnmowing equipment was patented with small gas-powered motors, cutting down on the labor required for landscape maintenance. This innovation was later supplemented by the availability of ready-mix concrete with which to pave once shell-strewn aisles. Finally, in the 1940s, industrialization of the monument and funerary industries led to most cemeteries eliminating the position of sexton (caretaker) from their ranks.

Each tumulus memorializes the fallen Confederate soldiers and deceased veterans associated with each division. After the Civil War, veterans of both Confederate and Union armies formed such benevolent associations for the support of their members. In the case of the Armies of Northern Virginia and Tennessee, perhaps the tumulus design was a nod to the military and fraternal connotations many ancient tumuli bear. Each tumulus features a remarkable sculpture at its hillside apex. The Army of Northern Virginia tumulus supports a 38-foot column atop which a sculpture of General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson stands. The Army of Tennessee features an equestrian bronze, sculpted by Alexander Doyle, depicting General Albert Sidney Johnston atop his horse, Fire Eater. Both tumuli are notable features of Metairie Cemetery, included in most histories of the cemetery.[7] The third notable tumulus in New Orleans is viewed daily by many city commuters. The tomb of the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, Lodge 30, features a bronze elk standing atop its grassy summit. The tumulus is located in Greenwood Cemetery at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, where the elk looks out above the traffic. The Elks lodge tumulus was first conceived of in 1911 by the local Elks, who held a great circus in downtown New Orleans to raise funds for the cause. In subsequent years, the Elks would commission monument man Albert Weiblen to construct the tomb at the cost of $10,000 (approximately $250,000 in 2016 currency). The structure was assembled of Alabama granite, shaped with a classical pediment, the center of which features a clock forever frozen at the eleventh hour, a reference to the “Eleventh Hour Toast” held by Elks when gathered together. Local legend has suggested that Albert Weiblen warned the Elks that the lot on which they wished the tumulus be constructed was not suitable for a structure of that size. It is true that, historically, City Park Avenue was once part of a navigation canal, an infill had only partially stabilized the soft earth. The story goes that the Elks decried Weiblen’s warning and enjoined he move ahead with construction. While primary sources for this story are nonexistent, the Elks Lodge tumulus does have a noticeable tilt toward Canal Street. Lessons in Preservation While the tumulus holds its place of honor in cemetery landscapes with the Elks and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia, it has faded from the everyday view of most cemeteries. Such a loss is difficult to quantify. Historic New Orleans cemeteries are dynamic places where features are constantly altered, modified, destroyed, or restored. Yet as we approach the task of preserving these cemeteries as functional landscapes, the tumulus offer some distinct lessons. Stripped-down tumuli confuse the historic appearance of cemeteries like Cypress Grove and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Had these structures been preserved, their green mounds would carry on the tradition of the cemetery as garden space; and they would properly communicate the historic landscape for both grieving family and heritage tourist alike. Stripped-down tumuli are an example of one cardinal rule of cemetery preservation: that once improper treatment has taken place, it’s nearly impossible to reverse. Each blow to responsible and considerate preservation is most likely permanent. Thus, while restoration is important, maintenance, documentation, and planned preservation are much more crucial. When the cemetery landscape is understood and preserved, large-scale restorations are less necessary. Finally, stripped-down tumuli teach us to deeply consider each structure as part of a whole, to read the structure for what isn’t there as much as for what is. Through this consideration, cemetery stewards can preserve these resources of history and heritage in a responsible manner that benefits generations to come. [1] Dan Hicks, et. al. Envisioning Landscape: Situations and Standpoints in Archaeology and Heritage (Routledge, 2016), 167.

[2] James C. Southall, The Recent Origin of Man (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1875), 87-97. [3] “Jackson Mounds,” Daily Crescent, January 16, 1851; “Norwegian tumulus,” New Orleans Bulletin, April 8, 1874, 2; “Norwegian Tumulus,” Opelousas Journal, August 4, 1876, 1. [4] George F. Beyer, “The Mounds of Louisiana,” in Publications of the Louisiana Historical Society (New Orleans: 1895), 12-30. (Link) [5] Gibbes tumulus, Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, SC, and HABS documentation (Library of Congress). [6] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1885, p. 2. [7] Henri Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery, An Historical Memoir: Tales of its statesmen, soldiers, and great families (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, 1981). Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. Beyond sweeping landscapes and imposing architecture – within the “stories in stone” that are so beloved in New Orleans cemeteries, are the stones themselves. Much like the long-dead people they memorialize, these slabs of honed and carved limestone, marble, and granite journeyed great distances to become part of an irreplaceable cemetery landscape. Whose hands drew that stone from its quarry? Why is the marble found in Greenwood Cemetery drastically different from what we find in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2? Today we share the stories of quarries, infrastructures, and materials that make up New Orleans cemetery stonework. Louisiana Lacks Workable Native Stone The geology of southern Louisiana is similar to that of other states along the Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of mostly sedimentary rock, clay, limestone, and sandstone, Louisiana has few stone resources that would be desirable for cemetery monuments.[1] Furthermore, the stone that is quarried in Louisiana has historically been of poor quality for building. For example, during the 1850s construction of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., requests were made that each state donate a block of native stone to be placed in the interior of the monument. Louisiana sent a block of sandstone that, within the decade, was so crumbling and decayed that it was replaced with a block of Pennsylvania marble.[2] Thus, from the eighteenth century onward, the stone used in New Orleans cemeteries was imported from elsewhere. Various types of slate, marble, and granite were made available as trade routes and quarries opened. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans merchants and dealers offered stone from a number of different places. As time went on, the availability and sources of stone widened.

Arkansas slate was quarried from areas near the towns of Hot Springs, Little Rock, Benton, Malvern, or Mena. This small vein of quality slate, approximately 100 miles long, could produce stone of red, gray, green, or black appearance. Despite the availability of slate from Arkansas, Pennsylvania slate continued to be quarried and shipped to New Orleans. Historic Louisiana newspapers frequently mention the quality and availability of slate from the Bangor quarry in Northampton County. Given the same name as a slate quarry in Wales, the “Old Bangor” quarry had an office in New Orleans by the 1870s. Old Bangor slate is “very dark gray, and to the unaided eye has a fine texture and fine cleavage surface, almost without any luster. The sawn edge shows pyrite.” The Williamstown, Franklin, and Pen Arygl quarries of Pennsylvania also had retail agents in New Orleans, who advertised their slate to be of the same quality as that of Wales.[6]

They form by the compression of these sediments, along with all the calcium-rich seashells within. They diverge when these sediments either compress and become sedimentary rock or, alternatively, are subject to higher pressures and become metamorphic. Limestone is sedimentary, marble is metamorphic. Limestone is most prevalent in the oldest remaining New Orleans cemeteries, namely St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, although precious isolated examples are found in other cemeteries. In this context, limestone was used for closure tablets. Limestone closure tablets are usually dark gray (likely quarried in Arkansas or Tennessee) and can be identified by the tiny fossilized shells included in the stone’s matrix. Around the mid-nineteenth century, whiter limestones were used in the same context as marble and are harder to identify. Some rough-faced stones that appear to be marble can be identified as limestone by spotting the shell inclusions within. These rare examples of white limestone were often quarried in Tennessee. Imported Marble: An Italian Commodity New Orleans was a primary hub for the import and export marble from both Europe and the United States. Used for closure tablets, shelves, memorial sculpture, apex sculptures, tomb cladding, and other decorative elements, marble was the medium in which cemetery stonecutters primarily worked throughout the nineteenth century. Based on documentary evidence, the quarries of Italy were the primary source of marble into the 1850s. Italian marble was either directly imported from Italy or arrived via northeastern ports like Boston or New York.[7] Florville Foy, who advertised aggressively throughout his career, frequently promoted his most recent shipment from Carrara or Genoa, cut into one, two, and three inch slabs. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux similarly advertised his Italian marble stock.[8] New Orleans stonecutters dealt in and imported Italian marble through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, stonecutter John Hagan (active 1854 – 1890s) stocked Italian marble “for sale at a small advance on New York prices.” George Stroud (active 1866 – 1899) cut his own Italian marble at Monsseaux’s steam cutting plant. James Reynolds (active 1866 – 1880) not only sold his Italian marble in New Orleans but also in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[9] Italian marble, often vernacularly referred to as “Carrara marble” regardless of its quarry of origin, is a stone of high-grade, consistent quality, and a variety of colors including cream, pure white, and blue. As one Alabama quarry owner conceded in 1909, “Italian marble has long been a standard, not only because the stone is undeniably high grade, but also because the blocks are so uniform in quality that all the slabs or pieces from a block can be used together.”[10] The cost of importing marble in New Orleans varied over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century; at times, it actually cost less to import than marble from Vermont or Tennessee. Protective tariffs helped to stabilize the marble industry during the 1880s and 1890s, but the presence of the famed marble remained a factor among monumental craftsmen into the present. For example, in 1914, before Albert Weiblen purchased his own marble quarry in Georgia, he received a shipment of Italian marble so substantial it took two large derricks to lift the fifteen-ton blocks from the steamship in which it arrived.[11] Domestic Marble: Vermont, Alabama, Georgia, and Others The slow development of infrastructure and quarry technology prevented American quarries from competing with Italian marble in New Orleans until the 1850s. In 1845, one of the first marble quarries opened in Talladega County, Alabama. Five years later, another opened nearby, operated by J.M.N.B. Nix. Using a publicity tactic that would become common among quarry operators in the United States, the New Orleans Daily Picayune announced that “Alabama produces marble equal in fineness – that is, purity or clearness and susceptibility of polish – to any in the world, not excepting the most beautiful Italian, Vermont, or Egyptian.” It was Nix’s quarry that sent Alabama’s contribution to the Washington Monument.[12] Talladega marble can appear white, blue, or cream, and often displays black, green, or grey veins, although it is consistently characterized by the fineness of its grain. Its unpredictability in quality and appearance, however, made it costly to extract.[13] Alabama marble remained a presence among New Orleans cemetery craftsmen well into the twentieth century. One of the most recognizable and imposing monuments within Metairie Cemetery, the ornate sarcophagus of Eugene Lacosst, was crafted by Albert Weiblen from pure white Alabama marble.[14] As always, infrastructure dictated which materials were available in New Orleans at a given time period. In 1851, The Vermont Valley Railroad Company connected towns like Rutland to the greater markets in the East and South.[15] Only two years later, sources in New Orleans commented on the great productivity of the Rutland quarries, remarking that their product had gained “a reputation abroad as well as at home.”[16] Rutland and other Vermont marbles can be white, blue, or black. These quarries also produced pure-white sculpture-grade marble.[17] By 1900, Vermont produced more marble than any other American state, and the Rutland quarry was the highest-yielding quarry. Blocks of Vermont marble were sold for between $1.00 and $3.00 per cubic foot in New Orleans, where agents received shipments and distributed order throughout the South and West.[18] Like Alabama marble, marble quarried in Vermont remained in the stockpiles of New Orleans craftsmen into the mid- and late twentieth century. Vermont not only exported its marble to New Orleans, but its marble cutters as well. One account reflected that the stone cutting yards of New Orleans primarily employed skilled sculptors and polishers from the states of Vermont and Georgia.[19] By 1916, Georgia was second only to Vermont in its production of quarried marble. Although marble quarrying had existed in Georgia long before, it appears to only have gained prevalence in the New Orleans market after the Civil War. By 1888, the Georgia Marble Company in Pickens County claimed to be the largest marble quarry in the world.[20] Georgia marble is typically coarse-grained and appears in blue-gray, black, white, and Creole, which has dramatic sweeping shades of dark gray, black, and white.[21] Ubiquitous Georgia Creole Marble Between 1890 and the 1930s, Georgia Creole marble exploded in the New Orleans cemetery market and made an enormous mark on the landscape. This explosion was the result of expert marketing, improved infrastructure, and enormous supply. Modern monument men during this period utilized Georgia Creole marble in nearly every aspect of their work, from tomb cladding to headstones to vases and urns. The streamlined process of tomb building, now executed in a more “cookie cutter” style than previous generations, allowed many more tombs to be built in a short period of time, and Georgia Creole marble was the medium of choice.

Additionally, as marble is a metamorphosed type of limestone, it is naturally alkaline in quality. Thus, exposure to rain, which is naturally slightly acidic, or any other acidic substance (for example, hydrochloric acid mistakenly intended to clean the stone) will cause marble to granulate and “sugar” over time. An extreme example of marble deterioration can be found in St. Joseph’s Cemetery No. 1. The failure that likely occurred with this stone was related to moisture entrapment within the tomb itself. This, paired with the tight, compressive position of the tablet within the opening, caused the closure tablet to bow and “bubble” outward.

One of the most noticeable granite tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is that of stonecutter and sexton James Hagan. This remarkable tomb was built of red-colored Scotch granite in 1872. Around the same time, Hagan also constructed the monument of Governor Henry Allen, which was also located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 until it was moved to the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the 1880s. This monument, too, was carved from Scotch granite.[24]

[1] Louisiana Geological Survey, Geology and Agriculture: A Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1902), 133-134.

[2] National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Northeast Region, Architectural Preservation Division, The Washington Monument: A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2005), 28. “Washington National Monument,” The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 22, 1850, page 1. The stone is referred to as “freestone,” meaning a soft, friable sedimentary stone. [3] Graham R. Thompson and Jonathan Turk, Introduction to Physical Geology (Rochester, NY: Saunders College Publishers, 1998), 133-137. Slate headstones are found commonly in the Northeast dating to the colonial period. Slate headstones are also present in cemeteries as far south as Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. However, no slate headstones are visible in the cemetery landscapes of New Orleans. [4] Mary Louise Christovich, Roulhac Toledano, and Betsy Swanson, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. I: The American Sector (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 1998), 57. [5] Daily Picayune, September 27, 1850, 2; Daily Picayune, May 2, 1853, 1; Daily Picayune, February 28, 1869, 11. [6] “Alexander Hill, Welsh and American Slates, Slabs, etc.” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 4, 1875, 6. These slates priced from $6.50 to $10 per square; “Slates! Slates! Slates!” Ouachita Telegraph (Monroe, LA), July 22, 1872, 2. [7] “Brig Casket arrives from New York with sundry marble slabs,” Louisiana Advertiser, April 29, 1820, 3. “Barelli & Company, commission merchants, selling blocks of Italian marble,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1845, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 10, 1848, 7; Daily Picayune, February 17, 1848, 3; Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1851 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1851), page AT. [9] Edwards’ Annual Director to the Inhabitants, Institutions….etc., etc., in the City of New Orleans for 1871 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1870), 275; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [10] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. [11] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8. [12] “Alabama Marble,” Daily Picayune, October 1, 1845, page 2; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [13] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. In this year, cost to transport Alabama marble to New Orleans was 32 cents per cubic foot. [14] Leonard V. Huber et. al. New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 54-55. [15] Vermont Railroad Commissioner, Eleventh Biennial Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of Vermont (St. Albans, VT: St. Albans Messenger Co., 1908), 308. [16] Daily Picayune, July 15, 1853, page1; Daily Picayune, June 16, 1855, 1. [17] Thomas Nelson Dale, The Commercial Marbles of Western Vermont (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 117-122. [18] Tariff Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means, Second Session, Fifty-Fourth Congress, 1896-97, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 275-279; “Random Notes,” The Reporter: The First and Only Journal Published in the World Devoted Exclusively to Granite and Marble, No. 1 (January, 1900): 33. [19] David Spence Hill, Industry and Education: Part Two of a Vocational Survey for Isaac Delgado Central Trades School (New Orleans: The Commission Council, 1916), 227. [20] “Science and Industry,” The Colfax Chronicle (Colfax, LA), November 3, 1888, 3. This was not an uncommon claim for many quarries to make. “Georgia Quarries,” The True Democrat (Bayou Sara, LA), January 30, 1897, 7. [21] Memoirs of Georgia, Vol. I (Atlanta: The Southern Historical Association, 1895), 211-217. [22] A. Oakley Hall, “Cities of the Dead,” in Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers Tales and Literary Journeys, Frank de Caro, editor. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998), 532-533; Arthur Wellington Brayley, History of the Granite Industry of New England, Volume I (Boston: National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913), 114. [23] Ibid., 84. [24] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley of Durham University, UK, for his knowledge and expertise in identifying the Hagan tomb as Scottish granite. [25] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1895), 1095. [26] “Notes from the Quarries,” Stone: an Illustrated Magazine Vol. 4 (1892): 496. During Mardi Gras season, New Orleans sees increased tourist traffic to one of its most popular attractions: its cemeteries, particularly Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. It nearly seems counterintuitive to visit a place of death and remembrance on a trip so populated with mirth and celebration. Yet the relationship of New Orleans cemeteries to its carnival celebrations is much richer than simply beads on wrought iron or the odd Muses shoe left on a tomb shelf. While the Carnival celebration is one of life and vivacity, the themes of mortality and cemeteries often creep into the mix. From death-themed floats, krewes, and costumes to actual celebrations in the cemeteries themselves, our cities of the dead have been part of the Mardi Gras stage since the 19th century.

The first (and last) Jewish man to serve as Rex in New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, Salomon later moved to New York, although he visited New Orleans each year for Mardi Gras for decades after his reign. He died in 1925 and, surprisingly, it appears as if no one knows where he was buried. His final resting place seems to remain a mystery. His sister Delia, however, married local liquor dealer Otto Karstendiek and, upon her death in 1866, was buried in the only cast-iron tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Lewis Salomon was remembered as the first Rex for decades after his great parade. And although his final resting place may remain a mystery, it stands to reason that it does, in fact, exist someplace. Unfortunately, neither of these things were true for the third King of Carnival, Rex 1874, A.W. Merriam.

Merriam’s funeral was held days later and, in an even more tragic turn of fortune, his moral remains were paraded to Girod Street Cemetery, where he was interred.[1] While the old king may have rested in peace for as long as seventy years, Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957. Whether the remains of A.W. Merriam were transferred to Hope Mausoleum (as all unclaimed remains of white people reportedly were) or elsewhere, or at all, is anyone’s guess. No record concerning Girod Street Cemetery includes his name. Rex rules his chaotic kingdom for a day. He is emblematic of both disarray and refinement, satire and grace. Upon the close of the evening on Shrove Tuesday, when Rex has met with the Court of Comus and the curtain is drawn on the season, Rex relinquishes his rule until next year, when he returns in the guise of another man. For most of those who served as Rex, death and burial was a rather uneventful affair. Yet one King of Carnival would have a much greater impact on the cemeteries of New Orleans than simply being buried there. The Builder King In 1915, Mardi Gras took place on February 16. Rex this year was Ernest Lee Jahncke, who “headed the procession on a golden chariot of state symbolic of his imperial power… crowned with jewels and wearing a mantle of cloth of gold, [sitting] upon the throne in the center of the car, gracefully acknowledging the plaudits of his subjects.” The theme that year was “Fragments from Sound and Story,” and featured such floats as “The Fatal Kiss of Undine (the water nymph)” and “The Barter of Mephistopheles,” illustrating the bargain of Dr. Faust with the devil.[2] Rear Admiral (USNR) Ernest L. Jahncke (1878-1960) served as assistant secretary of the Navy from 1929 to 1933 and was himself a “renowned yachtsman.[3]” He was the son of Fritz Jahncke (1847-1911), a German immigrant and founder of Jahncke Navigation Company. The elder Jahncke was instrumental in one of the greatest shifts in tomb construction in New Orleans history. Beginning in 1879, Jahncke was one of the first building supply dealers to make Portland cement available for his clients. While Portland cement had been available elsewhere in the country as early as the 1860s, its use was nearly unheard of in New Orleans prior to Jahncke’s business. Since the 1700s, builders in New Orleans cemeteries used mortars, stuccoes, and renders mixed from hydrated lime, a material procured from burning limestone or oyster shells in a kiln. These materials required protection from the elements, usually achieved by limewashing tombs on a regular basis.

The materials which Fritz Jahncke had made available to New Orleans cemetery builders would eventually replace lime-based stuccoes and shift the way tombs were constructed. Just as importantly, Jahncke established himself as a great paver, paving sidewalks and streets using new cement mixes and replacing the brick and shell-lined avenues that once marked neighborhoods and cemeteries. These materials in cemeteries cut down on the need to mow grass or perform other landscaping. An unintentional consequence of this paving process was the exacerbation of drainage issues in cemeteries which continue to this day. The Jahncke family expanded from serving as Mardi Gras royalty a century ago to owning a shipyard and a dry dock in addition to the cement company. Ernest continued these businesses into the twentieth century and long after his reign as Rex. He was, however, the Rex spokesperson who, in 1942, announced that Mardi Gras would be cancelled that year in the spirit of solemnity and frugality in the face of World War II. Both Ernest and Fritz Jahncke are buried in Metairie Cemetery. In the next installment of our examination of New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras history, we bring death to the party itself and check out cemetery and mortality-themed floats, krewes, and costumes.

Earlier this month, the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority of Seattle, Washington, announced the planned removal of an estimated one million pieces of chewing gum from the “gum wall” at Pike Place. Located within one of Seattle’s primary tourist destinations, the wall has become tourist destination in and of itself. In 2009, it was declared the second “germiest” tourist destination in the world – just behind the Blarney Stone.

Prior to 1999, it would have been difficult for a casual tourist to know that part of the “Pike Place experience” was to stick used chewing gum on a wall. To be sure, some visitors accompanied by tour guides may have been regaled with stories of this unusual tradition. But without a tour guide the wall would nary have been touched with tourist gum. Guide books did not even include the gum wall until after 2008 – we checked. Alone, the gum wall doesn’t really illustrate much other than a gross and “quirky” tourist tradition. But seen through a lens of lipstick, locks, and tourism, it illustrates an issue all cities seeking to woo tourism dollars should take into account.

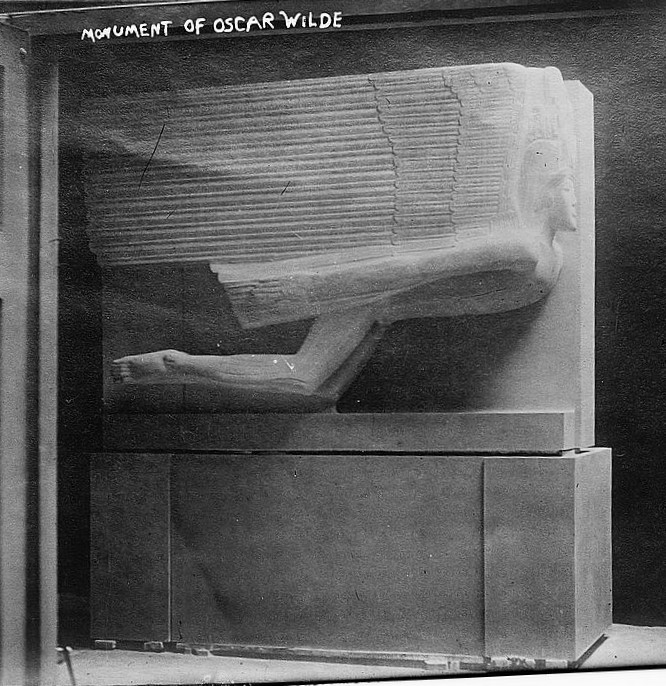

Installed in 1914, the sculpture (by Jacob Epstein, entitled The Sphinx) depicts an angel with male anatomy, which has been the target of mischief for nearly a century. Yet the worst threat to the sculpture arose much more recently. In the 1990s, it is reported, one lipstick kiss was placed upon the limestone marker. In the next twenty years, the load of lipstick marks on limestone became overwhelming, threatening to compromise the piece irreversibly. In 2013, this monument was the third-ranked germiest tourist attraction in the world. Thanks to efforts from the French and Irish governments amounting to more than €50,000, the statue was restored. A plexiglass barrier was installed around the burial place. At present, the plexiglass is inundated regularly with lipstick marks. For New Orleaneans, a lot of these seemingly unrelated local peccadilloes should sound very familiar. Each is a small act executed by tourists involving an easy-to-come-by medium: gum, locks, or lipstick. Many of these things travelers already have in their possession. They each have a somewhat weak background story connecting the tradition to the lure or the romance of the place. They each involve a literal way for an individual to “make a mark” on a place visited - to take part in something larger than themselves. They each began or expanded drastically after the late 1990s. Each of these traditions is innately destructive to historic and cultural resources. However romantic, fun, and exciting these traditions are, they amount to little more than participatory vandalism. All of these traditions have become part of travel-blog echo chambers which have fed the impression that the “tradition” is real and encouraged vandalism far beyond the useful life of click-bait entertainment. We would link to the hundreds of examples of “10 landmarks you must deface while in Paris,” but we work hard not to encourage that type of behavior. For sixty years, New Orleans had its own invented tourist tradition with which to contend. Beginning with a tourist brochure in the mid-1940s, the presumed tomb of voodoo icon Marie Laveau was repeatedly marked in accordance with a contrived wish-making ritual. The majority of these marks were created with similar items to those found in Père Lachaise – lipstick and pens. Although a constant presence in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 for decades, photographic documentation shows that the frequency of vandalism on the tomb increased after the late 1990s. Like Paris and Seattle, this phenomenon is likely related to the widened availability of “off the beaten path” tourism guides and social media resources online. While invented traditions are nothing new, the population of visitors who are likely to participate in them has grown enough that their impact is becoming increasingly difficult to manage. In 2014, New Orleans joined its Parisian counterparts in combating harmful participatory vandalism. The paired efforts of removing vandalism from cemetery property and restricting access to St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 resulted in a measurable decrease in tourist impact. Like Paris, interventions are often costly and can compromise historic resources with the introduction of protective materials (for example, plexiglass is not historic). Intervention can also require an immense investment of resources which may be needed elsewhere. In the moment, it is easy to perceive each incident of tourist “tradition” impact as isolated. Yet the recurrence of this phenomenon in tourism-driven economies proves they do not occur in a vacuum. Little research has been conducted that compares the similarities of such incidents from city to city, or the efficacy of treatment and prevention approaches. New Orleans is unique in so many ways, yet it faces the same difficulties of impact-management and preservation as any other tourism-based economy. It is time to closely examine the impact of perceived “traditions” and other behavioral cues on the preservation of our historic resources. Otherwise, it will not be long before one lipstick kiss snowballs into another expensive debacle. For other great insights on participatory vandalism and invented traditions:

NO LOVE LOCKS™ “No Love Lost on Love Locks,” Laura O’Brien “The Tipping Point Between Vandalism and Art,” Johana Desta, Mashable.com Final part in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. November 1945: six months after victory in Europe and three months since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In New Orleans as much as elsewhere, communities recovered from four years of total war. In the weeks leading up to All Saints’ Day, preparations for those who died overseas was a topic of discussion. Many of these soldiers would not come home at all. The American Battle Monuments Commission, which had been founded in 1923, would establish fifteen foreign monuments and cemeteries in Europe, the Pacific, and Tunisia to memorialize fallen soldiers. In April of 1945, the war department announced 5,335,500 newly available burial plots in 79 existing and new cemeteries.[1] This number seems enormous until we remember that 16.1 million Americans served in World War II. About 300,000 died in service.

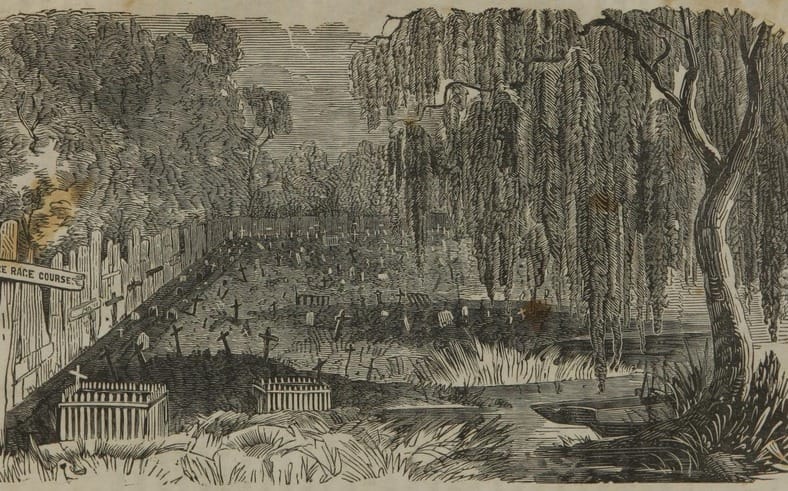

As early as mid-October 1945, hardware stores advertised items specifically for tomb care, including “Rock-Tite cement paint, which…is waterproof, tends to seal tomb corners, and lasts for years.” In many cases these materials were ultimately harmful to soft lime-stucco and brick tombs. Yet 1945 heralded a long (and ongoing) boom of new, strong, and user-friendly materials that would widely be seen in New Orleans cemeteries. This technological and cultural boom contrasted with some of the oldest cemeteries in the city, which were seen as outdated and, at worst, nuisances. Such was the case for Girod Street Cemetery. The Protestant cemetery, founded in 1822, had long been considered an eyesore. As early as the 1880s, the state government of Louisiana considered closing the low-lying cemetery altogether. By the 1940s, its condition was such that cemetery authorities took action. In 1945, officials at Christ Church Cathedral conducted a survey of Girod Street – “the first Protestant burial ground in the Lower Mississippi Valley" – and concluded that “some 1000 of the old vaults and tombs in which many of the city’s prominent and wealthy families were buried are a menace to public health.[4]” Each of these vaults and tombs was marked on All Saints’ Day 1945, and posted with a notice to families that the tombs must be repaired within 60 days. If no action was taken, said the city public health department, the tombs must be demolished. Reports from the sexton of Girod Street Cemetery suggested that as many as forty families did respond to the notices. However, it was too late for Girod Street Cemetery. The burial ground was deconsecrated in 1957 and demolished. The remains of white bodies were re-interred in Hope Mausoleum, and burials of African Americans were interred at Providence Memorial Park. [1] “Move to Return War Dead Begun,” Times-Picayune, April 5, 1945, 27.

[2] “Orleanians Plan Halloween Observance in Usual Style,” Times-Picayune, October 31, 1945, 4. [3] “Up and Down the Street,” Times-Picayune, October 11, 1945, 34. [4] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945, 12; “Girod Cemetery Inspected,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945, 5. Part Three of Three Brickmaking in the Late Nineteenth Century Expanding infrastructure and advancing technology led to a number of advances in brickmaking after the Civil War. These processes included dry-pressing, in which denser clay is compressed using steam-powered equipment, and extruding, in which the mold is abandoned for extruded clay cut with wires. In buildings, New Orleans saw entirely new materials like terra cotta and cast-iron storefronts. In New Orleans cemeteries, terra cotta was never established as a structural material. However, cast-iron companies like Wood, Miltenberger & Co. expanded their market by building catalog-ordered iron tombs. New Orleans has more than one dozen of these tombs remaining. In cemeteries, red river brick was almost entirely phased out, although many brickyards still produced them.[1] Many bricks found in tombs of this era show different variations in color, texture, and inclusions, but much are similar to “hard tans,” indicating sources in St. Tammany Parish. This is likely, as even more brickyards developed there after 1865.[2]  from the St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. Image courtesy Library of Congress. from the St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. Image courtesy Library of Congress. Among the St. Tammany brickyards to establish and grow in the late 19th century was St. Joe Brick Company. Founded in 1891, St. Joe Brick used (and still uses) wooden molds for brick manufacture. St. Joe bricks, are found throughout New Orleans cemeteries, where their porousness, dimension, and breathability suited tombs coated in lime stucco. Entire tombs were constructed using exclusively St. Joe Brick. Today, St. Joe bricks can still be purchased from the company’s Pearl River yard and other distributors. Like historic salvaged bricks, they mimic the qualities builders sought in historic building materials.[3] New Materials and Methods From the turn of the century, industrialized building materials inched further and further into the New Orleans cemetery landscape. Most notably, modern cements became more and more available until, after World War II, they were the norm. This meant Portland cement stucco replacing lime. But it also meant the rise of cast concrete, cast stone, and concrete block. A notable example of this was Dognibene Architectural Cast Stone, a company that seems to have dealt primarily with garden features and pottery, but also built tombs. Three Dognibene tombs are known to exist from the 1920s: Two in Hook and Ladder Cemetery (Gretna), and one in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Today, New Orleans bricks are more important to cemetery preservation than ever. Most historic tombs, especially those in need of repair or attention, require brick replacement, a difficult task in a world where traditional brickmaking is all but phased out. The desire for historic brick to be used in walls, paving, and historic buildings also put tombs at risk of brick theft, an incident that is all too common. Even more material is lost to unsympathetic repairs applied to soft brick which can constrict materials and cause cracking, breaking, or even structural failure.

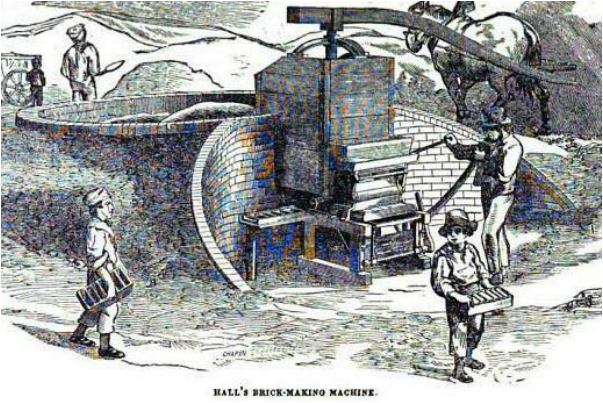

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC only uses historically-appropriate brick for repairs. Where brick must be replaced, brick of similar density and dimension is chosen – we do not salvage bricks from other cemeteries or tombs. You never know who will come back to care for their historic burial place. [1] American Engineer, Vol. 16 (July 1888), 13. [2] “Tammany Steam Brick Yard,” Times Picayune, December 24, 1871, 15; “Lake Brick for Sale,” St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. [3] “History of St. Joe Brick Works,” http://www.stjoebrickworks.com/history.html; Dave Macnamara, “Heart of Louisiana: St. Joe Brick Works,” Fox 8 Live, January 11, 2013, http://www.fox8live.com/story/19517618/heart-of-louisiana-st-joe-brickworks. Part Two of Three The Little Red Row-house in the Cemetery By the 1830s, brickmaking processes were slowly industrializing in the Northeast and along the Eastern Seaboard. The introduction of hand-operated pressing machines led to the production of bricks with smoother edges. Other developments that tempered and cut clay using wires also arose. While these processes would eventually be introduced to New Orleans brickmakers, the clean, dense, fine-edged bricks they produced would be especially associated with northern cities like Philadelphia. In the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the “Protestant Section” is dominated by below-ground burials, a feature attributed to the cultural inclination of non-Catholics toward in-ground burial regardless of circumstances. Those burials which are accommodated by above-ground tombs are distinguished by construction using bricks that would sooner be at home in a northern row-house than a New Orleans tomb. The tombs of the Layton and Johnson families exhibit this brick for tomb construction. The tradition expanded beyond the 1830s, as exhibited by the multiple pressed red-brick tombs associated with Northern-born families in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Unlike traditional New Orleans tombs, these bricks were likely meant to be bare, without stucco. Brick Making Machines and Labor Beginning in the 1840s and likely earlier, brickmaking machines of all different types arose in New Orleans. The first machines were modifications of the “pug mill,” an apparatus by which brickmaking clay is churned and cured in order to make it suitable for molding. In 1848, John Hoey prominently advertised the construction of Hall’s “patent brickmaking machine” on his property near Bayou St. John.[1] This machine was essentially a pug mill in which clay was churned, cured, and extruded into molds. A number of additional brickyards developed along the Carondelet Canal, which ran from Bayou St. John past St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, terminating at Basin Street. Into the 1920s, “Carondelet Walk” featured a great deal of the city’s brick yards, from which bricks could be milled, fired, and transported for sale. Other brick yards thrived along the Mississippi River at Tchoupitoulas Street. In the Riverbend area, a brickyard operated a version of a Hoffman Kiln, another patented machine by which bricks were fired in a rotating sequence. By the 1850s, a number of steam-powered brick-making operations existed along the Gulf Coast in Biloxi, Mobile, and Thibodeaux, which supplied New Orleans markets.[1]

Prior to 1865, most of these operations, as well as smaller brick-making industries on plantation land, were operated by enslaved African Americans who were skilled in trade. In one instance, Gabriel Parker of St. Tammany Parish came to own his own brickyard after emancipation. In many other instances, freed tradesmen passed on their skills to their children.[2] [1] “Biloxi Fire Brick,” Daily Crescent, July 29, 1850, 3; Daily Picayune, June 3, 1866, 3; “Hoffman’s Brick Making Kiln,” Daily Picayune, March 8, 1867, 2; The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans Daily Picayune: 1903), 41; “Brickmaking Machine,” Thibodaux Minerva, January 21, 1854, 3. [2] Ellis, St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac, 159; Crary, J.W., Sixty Years a Brickmaker: A Practical Treatise on Brickmaking and Burning and the Management and Use of Different Kinds of Clays and Kilns for Burning Brick (Indianapolis: T.A. Randall & Co., 1890), 36. Part One of Three “Reds” and “Tans” –hand-molded, wire-cut and pressed: Much can be learned from the bricks that comprise any one tomb. Brick identification can teach us about the construction date of the tomb, later alterations, quality of original construction, and cultural connections of the interred. It can help us understand the process of development in a cemetery, demolition and rebuilding, and where repairs were made. The history of New Orleans brick is as complex as its rich industrial and commercial history. However, the general narrative history of New Orleans brick is simple: “soft reds” were made from the clay of the Mississippi River, otherwise known as “batture,” and “hard tans” were made from the clays found around Lake Pontchartrain.[1] While this narrative is generally true, it belies the greater complexity of masonry in the Crescent City, in which new technologies and new commercial infrastructure compounded available brick types and styles. New Orleans River Brick New Orleans “soft reds” were likely the first masonry units manufactured in the city in the eighteenth century. Using the most basic and common of methods, brickmakers would mine batture from the river’s bank, allow it to dry, temper it, mold it, and fire it. Brick firing prior to the industrial revolution was almost exclusively accomplished without special equipment. Clay was molded in wooden molds, allowed to dry or cure, and then fired. These bricks can be bright or dull red, with soft edges. New Orleans “soft red” or “river brick” continued to be made through the nineteenth century. When we see red river brick in New Orleans cemeteries, their presence alone does not suggest early nineteenth century construction. However, soft reds are much more common in the oldest cemeteries in the city: St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, and to a lesser extent Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. We see them in single-vault step tombs, wall vaults, and other elements of cemetery landscapes that represent the earliest phases of construction. It should be mentioned here that, generally speaking, we should seldom see bricks at all. New Orleans reds are so soft that exposure to the humid elements and temperature cycles of our local climate can cause them to deteriorate. Historic craftsmen were aware of this and typically coated tombs with lime-based stucco, which protected the brick beneath. Stucco coating was also applied to hide the appearance of bricks which were irregular in size and edges and were not considered aesthetically pleasing.[2] “Lake” or St. Tammany Brick

New Orleans “tans,” historically referred to as “lake brick,” were similarly manufactured during the first half of the nineteenth century. Instead of river batture, they were created from clay sourced north and east of New Orleans. Typically, this meant deposits near Lake Pontchartrain, but a number of other sources in St. Tammany parish were also used.[1] The mineral content of St. Tammany clays produced a tan-colored brick, typically with dark inclusions of iron, bauxite, and other impurities. Such bricks were significantly more durable than river bricks.[2] While lake bricks became the standard for a great deal of city construction by the 1850s, there were no requirements for the construction of tombs. Alternately, city ordinance did require that all tombs be “plastered” with protective stucco, which meant that cheaper bricks could be utilized. For this reason it is not surprising that river bricks remained the norm in tomb construction until around the time of the Civil War. Hand-molded lake and river bricks were easily manufactured and acquired locally. Yet the hub of trade and growth that was nineteenth century New Orleans invited a great deal more in the way of building materials and masonry units. Furthermore, cemetery construction typically represents the aesthetic and construction tradition of the memorialized individual or individuals. The best example of this trend can be seen in the Protestant and other Northern-extracted cemeteries of the city.[3] [1] Ellis, Frederick S., St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1981, 108. [2] “An Ordinance to Establish a Ferry near the St. Mary’s Market, and Connected with the City of Lafayette,” True American, November 20, 1838, 1. [3] “Building Material, Bricks, Firewood,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, August 02, 1859, 4. Advertising brick from France, England, and America. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly