|

As any narrative on de Pouilly does, this article relies on the groundbreaking research and thesis of Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University thesis, 1992. Which exquisitely analyzed de Pouilly’s work in New Orleans cemeteries. One hundred and forty years ago, on February 21, 1875, Jacques Nicholas Bussiere de Pouilly died in his home on St. Ann Street. In his seventy years of life, de Pouilly had been the harbinger of European neoclassical and revival architecture in New Orleans. We see his touch on our city streets – in St. Augustine Catholic Church, and most notably St. Louis Cathedral. But his influence was arguably greatest in the city’s cemeteries. De Pouilly’s work is present in nearly every viewpoint of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, and much of Cypress Grove Cemetery. The breadth and innovation of his tomb architecture generated uncountable replications and inspirations, the products of which have shaped our burial grounds. J.N.B. de Pouilly was born in July 1804 in Châtel-Censoir, France, southeast of Paris. While much of his early life is unclear, it is assumed that in his architectural training he was influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, if not a student of the school himself.[1] He arrived in New Orleans in 1833, a time in which the French-speaking population of the city hungered for reconnection with Continental styles. He quickly became the architect of note for the city’s First District, designing the St. Louis Exchange Hotel, among many other residential, commercial, and religious projects.

While Père Lachaise and Creole cemeteries like St. Louis may appear stylistically similar, de Pouilly had the significant task of fundamentally shifting the function of his New Orleans tombs from their Parisian prototype. Although the monuments of Père Lachaise appear to be tombs or mausoleums, their design accommodates instead for below-ground burial. That the architect’s designs kept their Parisian aesthetic while having been fundamentally re-worked to allow for above-ground burial is among the more impressive of his professional achievements.[3]

In addition to the French St. Louis Cemeteries, de Pouilly worked also in American-dominated Cypress Grove Cemetery (est. 1840). In Cypress Grove, de Pouilly additionally contracted with granite magnate Newton Richards to build the memorial of fallen firefighter Irad Ferry (died 1837). He relied, too, on Monsseaux and Foy to construct such masterpieces as the Maunsel White tomb. De Pouilly clearly had a strong grasp on the value of trade and materials, based on his choice of craftsmen and his apparent innovations in the world of cast stone. De Pouilly’s career was marred by two construction disasters in the 1850s – first, the collapse of the central tower of St. Louis Cathedral while de Poilly was head architect, and second the collapse of a balcony at the Orleans Theatre. From this point onward, his rising star waned, but it appears never to have faded in New Orleans cemeteries. In 1874, de Pouilly composed the final drawing in his only surviving sketchbook – a tomb he designed for himself and his family. This tomb, like many depicted in his prolific sketches, would never be constructed. Instead, de Pouilly was interred in a family wall vault in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Although the location was surely not intentional, the wall provides a lovely view of a number of de Pouilly-designed tombs. In a nearly-illegible detail to his memorial tablet, the signature of Florville Foy can be detected as the carving hand of de Pouilly's final tablet. De Pouilly’s obituary on February 22nd spoke grandly of a man who lived honestly and in service of his profession:

St. Peter’s lofty dome cenotaphs the name of Michael Angelo [sic]: Sir Christopher Wren’s greatness is sepulchred in the mightiness of St. Paul’s. Mr. De Pouilly fashioned no wonders such as these, but yet a greater, the enduring fabric of an honest life, and will be entombed in the constant remembrance of devoted friends. After a painful and lingering illness, Mr. De Pouilly, hoary with the winters of seventy years, and surrounded by children and other relatives, bade farewell to things of earth. This sad event occurred yesterday, Sunday, 21st.[4] The Daily Picayune made no note of the many cenotaphs de Pouilly himself had helped write, in the tablets and along the aisles of our cemeteries. But if 140 years is a sufficient measure of the timelessness and impact of one’s work, his name certainly engraved upon many more memorials than just his own. Below is a gallery of only a portion of de Pouilly’s work, and a few tombs inspired by his designs. Photos by Emily Ford unless otherwise noted. [1] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” 5-7.

[2] Peggy McDowell and Richard E. Meyer, The Revival Styles in American Mortuary Art (Popular Press, 1994), 59. [3] Masson, 30-35. [4] “In Memoriam – J.N. de Pouilly,” Daily Picayune, February 22, 1875, 2.

7 Comments

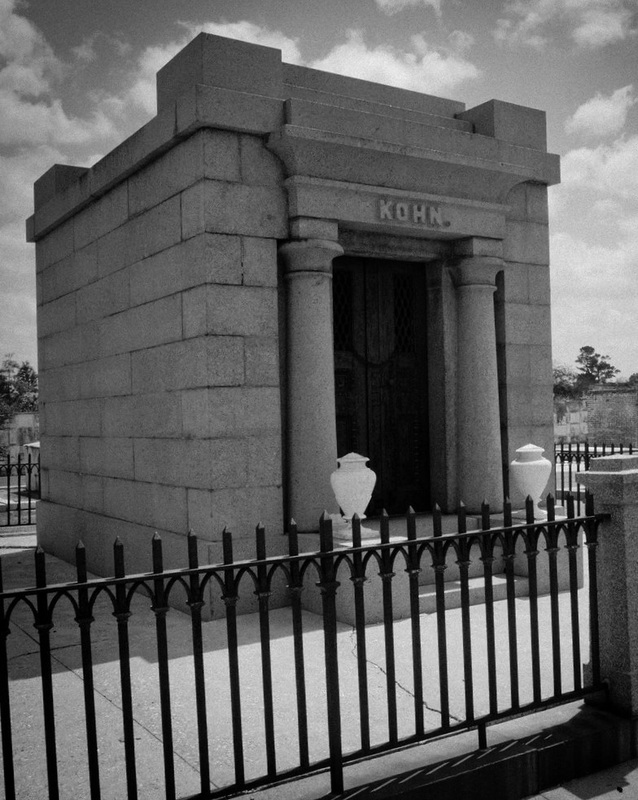

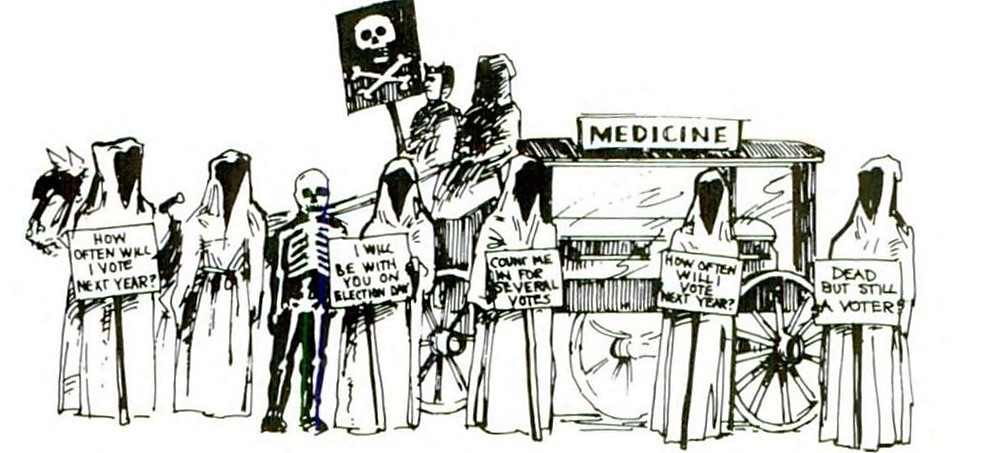

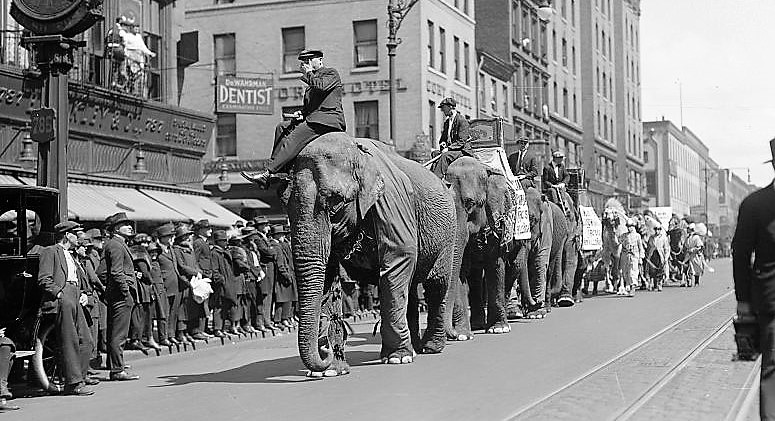

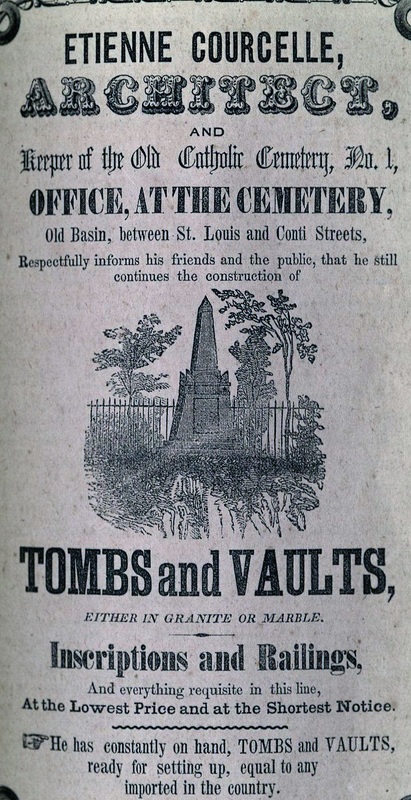

Over the past week, New Orleaneans have been treated to nightly parades in neighborhoods Uptown and downtown, on the West Bank and in Metairie. Today, Krewe of Thoth will ride down St. Charles Avenue, followed by Bacchus and others this evening. The fever pitch of Mardi Gras is upon us, culminating on Fat Tuesday, Mardi Gras Day. In the spirit of the season, we’ve mused on the place of cemeteries in Mardi Gras traditions – from the last resting places of Dead Rexes to the incorporation of death and cemeteries in costuming and floats. Seldom do Mardi Gras celebrations themselves take place in New Orleans cemeteries. But once or twice in a blue moon, amidst Storyville revelry or between the pages of a Gayarré novel, such things have happened. Today, on this Sunday before Mardi Gras, we explore the few instances of Mardi Gras dancing on the graves. The St. Louis Cemetery Marchers In one of the St. Louis Cemeteries, the dead were entertained by an especially satirical parade in 1911, when maskers dressed as deceased voters processed through the cemetery gates to follow the tail of the parade of Rex. The details of this event are discussed in two New Orleans histories, although primary accounts of the parade are scant. In what James Gill refers to as one of the “drollest examples” of political satire in Mardi Gras parades, marchers dressed as skeletons emerged from the cemetery holding signs marked, “Count me in for several votes,” “I’ll be with you on election day,” and “Dead, but still a voter.”[1] According to Buddy Stall’s New Orleans, the marchers labeled themselves “The Graveyard Pleasure Club,” “Girod Cemetery Voters League,” and “the Tombstone Brigade.”[2] The members of the St. Louis Cemetery Marchers were anonymous, although one marcher later revealed his identity to be Edouard F. Henriques, a local judge. He and other members were members of the Good Government League, part of the Progressive movement in Louisiana and, in the next year, supporters of “Bull Moose” presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt, much against the dominant Democratic "machine" in New Orleans. The Marchers emerged from St. Louis Cemetery (presumably No. 1, or possibly No. 2) after having “entertained the sexton” with their antics. They caught up to Rex and followed along its route, as one parade-goer remarked, “Their silent message is more meaningful than any spoken word I can imagine.” They continued behind the parade until police forces peacefully disbanded them, just before they reached City Hall. The Elks Burlesque Circus In the days leading up to the St. Louis Cemetery Marchers 1911 procession, a bigger, louder ruckus was taking place just blocks away. At Elks Place and Canal Street, a great circus would take place, complete with lion tamers, elephants, and acrobats. On the Friday before Mardi Gras, this circus paraded through the city, marching uptown as far as Felicity Street, and back through the Central Business District.[3] The enormous circus and parade were organized by the New Orleans Lodge No. 30, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, known casually as the Elks Lodge, and for whom Elks Place is named. If you live in New Orleans, you probably know them for their tomb, which looks out on the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The 1911 circus and parade, complete with a petting zoo of baby elks, was held as a fundraiser for an imposing tomb the Elks Lodge hoped to construct in Greenwood Cemetery. Elks members costumed as clowns and even traveled abroad to learn how to care for circus animals – said one article, “Quite a number of the antlered herd are taking corresponding lessons on how to manage elephants and camels.[4] The big top Mardi Gras-season fundraiser was as ambitious as the organization’s tomb plans. The Elks Lodge memorial is a tumulus: a burial chamber which has been covered in earth, making it resemble a hill or burial mound. While New Orleans is no stranger to tumuli – at one point in time, they were quite common in cemetery landscapes – the Elks Lodge tumulus is one of the most iconic of these structures in American cemeteries. The tumulus was constructed by Albert Weiblen at the cost of $10,000 – essentially $250,000 in 2016 dollars.[5] Its subterranean walls were topped with a giant boulder of Alabama granite, on top of which a nine-foot-tall bronze elk was erected. Two years and some minor (but noticeable) foundational issues later, the cemetery landmark was completed. Today, organizations with communal tombs and society burial places often find great difficulty in raising the capital needed to restore their deteriorating cemetery property. Perhaps it’s time once again to bring the circus to town for the benefit of our historic cemeteries. Tintin Calandro: The Mad Musician of the St. Louis Cemetery Our final Mardi Gras cemetery story is exactly that: a story. On this blog, we like to keep things factual, but in the spirit of the prankishness and surreality of Carnival, we recall the tale of Tintin Calandro. Celebrated New Orleans author Charles Gayarré (1805 – 1895) is memorialized in the city as its premiere 19th century historian. A beautiful terra-cotta memorial to him sits at the divergence of Esplanade Avenue and Bayou Road. He is best remembered for his History of Louisiana (1866), but he did write two novels as well, Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction (1872) and Aubert Dubayet (1882). Featured in both of these novels is Augustine Calandrano, more frequently referred to by the narrator as Tintin Calandro, French revolutionary exile, talented violin player, and eccentric sexton of St. Louis Cemetery. In Fernando de Lemos, Tintin Calandro is a “genius of madness,” each night serenading his ghostly charges:

Calandro and Fernando de Lemos have a special relationship in which they spend nights in the cemetery, discussing philosophy, love, ethics, and other profound topics amidst the tombs. Toward the end of Calandro’s life, it appears his fits of insanity worsened. Nearing his own death, the old sexton fought frailty and his better senses in order to go to the cemetery for a final concert, on Shrove Tuesday: He said that the ghosts were going to have a Mardi Gras ball and he wanted to open the event by playing an overture, after which an orchestra of spirits would supply the music… [the narrator] accompanied the musician to the cemetery. There Tintin greeted the ghosts, bade them be silent and seated, and then seating himself and his companion on a tombstone, he began to play. … In the spell which overcame him he saw the ghosts whisking past in the dance, and the mad excitement grew upon him until the sound of the violin was hushed. Then Tintin apologized to his visionary audience, and allowed his friend to escort him home.

[1] James Gill, Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans (University Press of Mississippi: 1997), 166.

[2] Buddy Stall, Buddy Stall’s New Orleans (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1990), 167-169. [3] “Elks Announce Route of Parade Preceding Burlesque Circus,” Daily Picayune, February 20, 1911, p. 2. [4] “Elks’ Circus to be a Feature During Carnival Week Here: Parade and Performances to be Filled with Features Farcy, Freakish and Funny,” Daily Picayune, January 15, 1911, 30; “Circus Catches: Pokorny’s Little Elks Arrive for Big Show,” Daily Picayune, February 17, 1911, 7. [5] “Elks’ Tomb to be Erected on Fine Greenwood Cemetery Site,” Daily Picayune, August 7, 1911, 7. [6] Excerpt from Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction, featured in The Southern Bivouac, Vol. II, No. 1 (June, 1886), 112-114; James A. Kaser, The New Orleans of Fiction: A Research Guide (Scarecrow Press: 2014), 92. [7] “Tintin Calandro: Judge Gayarré Tells the Story of the Mad Musician of St. Louis Cemetery,” Oachita Telegraph, January 20, 1887, 1. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly