|

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. Beyond sweeping landscapes and imposing architecture – within the “stories in stone” that are so beloved in New Orleans cemeteries, are the stones themselves. Much like the long-dead people they memorialize, these slabs of honed and carved limestone, marble, and granite journeyed great distances to become part of an irreplaceable cemetery landscape. Whose hands drew that stone from its quarry? Why is the marble found in Greenwood Cemetery drastically different from what we find in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2? Today we share the stories of quarries, infrastructures, and materials that make up New Orleans cemetery stonework. Louisiana Lacks Workable Native Stone The geology of southern Louisiana is similar to that of other states along the Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of mostly sedimentary rock, clay, limestone, and sandstone, Louisiana has few stone resources that would be desirable for cemetery monuments.[1] Furthermore, the stone that is quarried in Louisiana has historically been of poor quality for building. For example, during the 1850s construction of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., requests were made that each state donate a block of native stone to be placed in the interior of the monument. Louisiana sent a block of sandstone that, within the decade, was so crumbling and decayed that it was replaced with a block of Pennsylvania marble.[2] Thus, from the eighteenth century onward, the stone used in New Orleans cemeteries was imported from elsewhere. Various types of slate, marble, and granite were made available as trade routes and quarries opened. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans merchants and dealers offered stone from a number of different places. As time went on, the availability and sources of stone widened.

Arkansas slate was quarried from areas near the towns of Hot Springs, Little Rock, Benton, Malvern, or Mena. This small vein of quality slate, approximately 100 miles long, could produce stone of red, gray, green, or black appearance. Despite the availability of slate from Arkansas, Pennsylvania slate continued to be quarried and shipped to New Orleans. Historic Louisiana newspapers frequently mention the quality and availability of slate from the Bangor quarry in Northampton County. Given the same name as a slate quarry in Wales, the “Old Bangor” quarry had an office in New Orleans by the 1870s. Old Bangor slate is “very dark gray, and to the unaided eye has a fine texture and fine cleavage surface, almost without any luster. The sawn edge shows pyrite.” The Williamstown, Franklin, and Pen Arygl quarries of Pennsylvania also had retail agents in New Orleans, who advertised their slate to be of the same quality as that of Wales.[6]

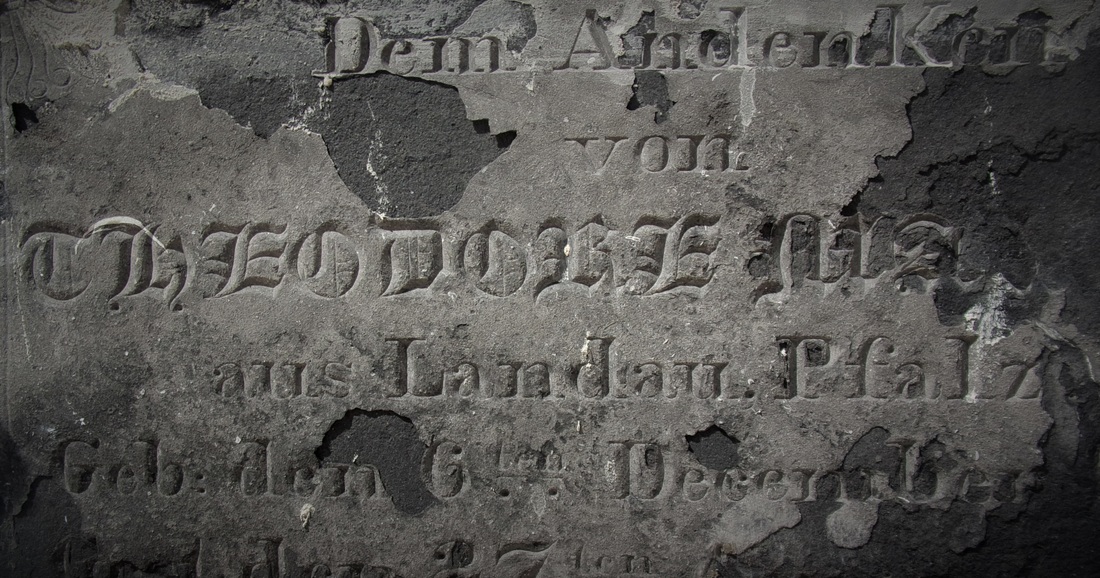

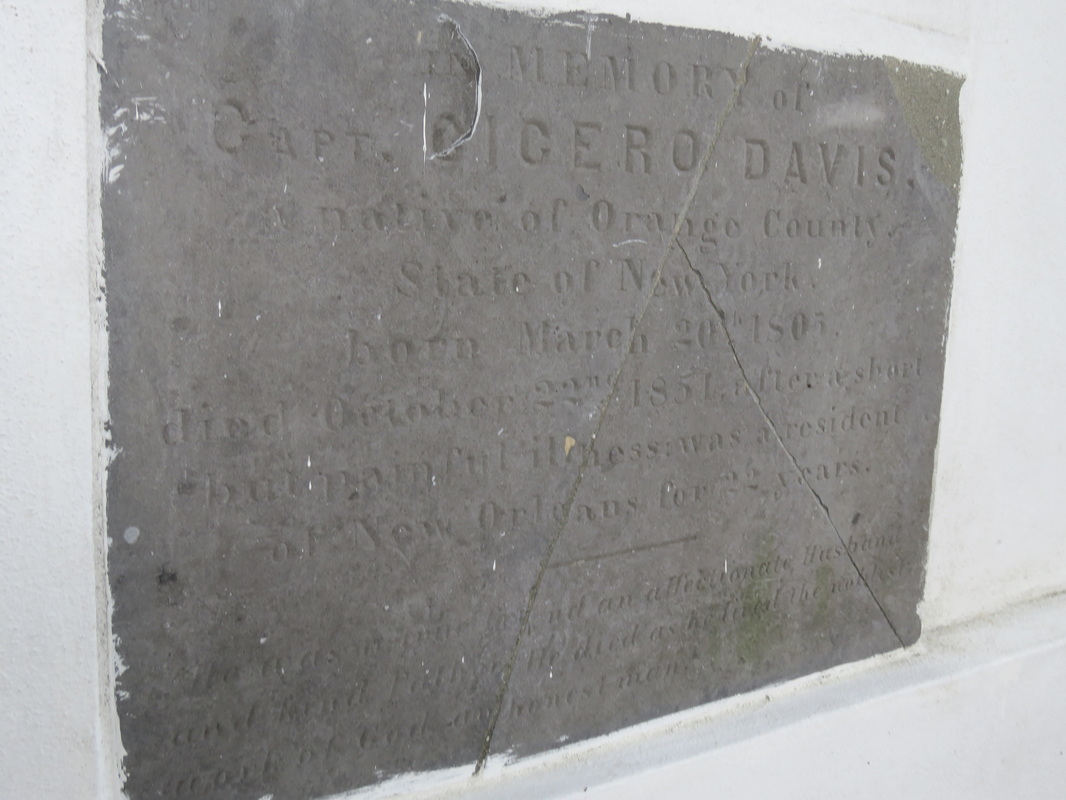

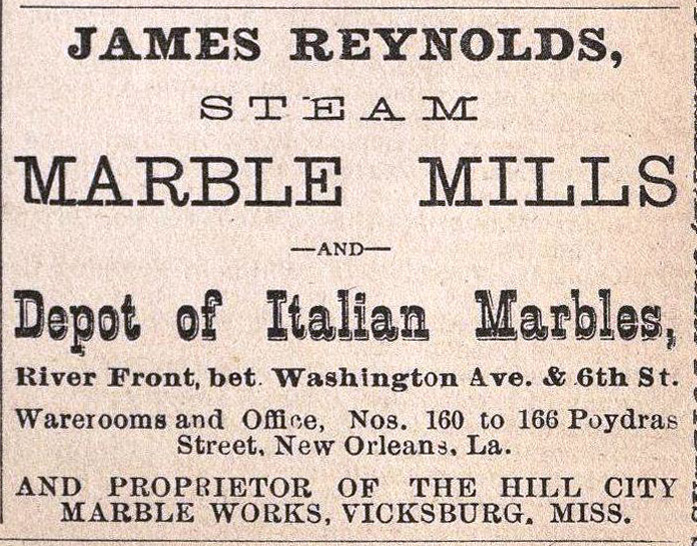

They form by the compression of these sediments, along with all the calcium-rich seashells within. They diverge when these sediments either compress and become sedimentary rock or, alternatively, are subject to higher pressures and become metamorphic. Limestone is sedimentary, marble is metamorphic. Limestone is most prevalent in the oldest remaining New Orleans cemeteries, namely St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, although precious isolated examples are found in other cemeteries. In this context, limestone was used for closure tablets. Limestone closure tablets are usually dark gray (likely quarried in Arkansas or Tennessee) and can be identified by the tiny fossilized shells included in the stone’s matrix. Around the mid-nineteenth century, whiter limestones were used in the same context as marble and are harder to identify. Some rough-faced stones that appear to be marble can be identified as limestone by spotting the shell inclusions within. These rare examples of white limestone were often quarried in Tennessee. Imported Marble: An Italian Commodity New Orleans was a primary hub for the import and export marble from both Europe and the United States. Used for closure tablets, shelves, memorial sculpture, apex sculptures, tomb cladding, and other decorative elements, marble was the medium in which cemetery stonecutters primarily worked throughout the nineteenth century. Based on documentary evidence, the quarries of Italy were the primary source of marble into the 1850s. Italian marble was either directly imported from Italy or arrived via northeastern ports like Boston or New York.[7] Florville Foy, who advertised aggressively throughout his career, frequently promoted his most recent shipment from Carrara or Genoa, cut into one, two, and three inch slabs. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux similarly advertised his Italian marble stock.[8] New Orleans stonecutters dealt in and imported Italian marble through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, stonecutter John Hagan (active 1854 – 1890s) stocked Italian marble “for sale at a small advance on New York prices.” George Stroud (active 1866 – 1899) cut his own Italian marble at Monsseaux’s steam cutting plant. James Reynolds (active 1866 – 1880) not only sold his Italian marble in New Orleans but also in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[9] Italian marble, often vernacularly referred to as “Carrara marble” regardless of its quarry of origin, is a stone of high-grade, consistent quality, and a variety of colors including cream, pure white, and blue. As one Alabama quarry owner conceded in 1909, “Italian marble has long been a standard, not only because the stone is undeniably high grade, but also because the blocks are so uniform in quality that all the slabs or pieces from a block can be used together.”[10] The cost of importing marble in New Orleans varied over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century; at times, it actually cost less to import than marble from Vermont or Tennessee. Protective tariffs helped to stabilize the marble industry during the 1880s and 1890s, but the presence of the famed marble remained a factor among monumental craftsmen into the present. For example, in 1914, before Albert Weiblen purchased his own marble quarry in Georgia, he received a shipment of Italian marble so substantial it took two large derricks to lift the fifteen-ton blocks from the steamship in which it arrived.[11] Domestic Marble: Vermont, Alabama, Georgia, and Others The slow development of infrastructure and quarry technology prevented American quarries from competing with Italian marble in New Orleans until the 1850s. In 1845, one of the first marble quarries opened in Talladega County, Alabama. Five years later, another opened nearby, operated by J.M.N.B. Nix. Using a publicity tactic that would become common among quarry operators in the United States, the New Orleans Daily Picayune announced that “Alabama produces marble equal in fineness – that is, purity or clearness and susceptibility of polish – to any in the world, not excepting the most beautiful Italian, Vermont, or Egyptian.” It was Nix’s quarry that sent Alabama’s contribution to the Washington Monument.[12] Talladega marble can appear white, blue, or cream, and often displays black, green, or grey veins, although it is consistently characterized by the fineness of its grain. Its unpredictability in quality and appearance, however, made it costly to extract.[13] Alabama marble remained a presence among New Orleans cemetery craftsmen well into the twentieth century. One of the most recognizable and imposing monuments within Metairie Cemetery, the ornate sarcophagus of Eugene Lacosst, was crafted by Albert Weiblen from pure white Alabama marble.[14] As always, infrastructure dictated which materials were available in New Orleans at a given time period. In 1851, The Vermont Valley Railroad Company connected towns like Rutland to the greater markets in the East and South.[15] Only two years later, sources in New Orleans commented on the great productivity of the Rutland quarries, remarking that their product had gained “a reputation abroad as well as at home.”[16] Rutland and other Vermont marbles can be white, blue, or black. These quarries also produced pure-white sculpture-grade marble.[17] By 1900, Vermont produced more marble than any other American state, and the Rutland quarry was the highest-yielding quarry. Blocks of Vermont marble were sold for between $1.00 and $3.00 per cubic foot in New Orleans, where agents received shipments and distributed order throughout the South and West.[18] Like Alabama marble, marble quarried in Vermont remained in the stockpiles of New Orleans craftsmen into the mid- and late twentieth century. Vermont not only exported its marble to New Orleans, but its marble cutters as well. One account reflected that the stone cutting yards of New Orleans primarily employed skilled sculptors and polishers from the states of Vermont and Georgia.[19] By 1916, Georgia was second only to Vermont in its production of quarried marble. Although marble quarrying had existed in Georgia long before, it appears to only have gained prevalence in the New Orleans market after the Civil War. By 1888, the Georgia Marble Company in Pickens County claimed to be the largest marble quarry in the world.[20] Georgia marble is typically coarse-grained and appears in blue-gray, black, white, and Creole, which has dramatic sweeping shades of dark gray, black, and white.[21] Ubiquitous Georgia Creole Marble Between 1890 and the 1930s, Georgia Creole marble exploded in the New Orleans cemetery market and made an enormous mark on the landscape. This explosion was the result of expert marketing, improved infrastructure, and enormous supply. Modern monument men during this period utilized Georgia Creole marble in nearly every aspect of their work, from tomb cladding to headstones to vases and urns. The streamlined process of tomb building, now executed in a more “cookie cutter” style than previous generations, allowed many more tombs to be built in a short period of time, and Georgia Creole marble was the medium of choice.

Additionally, as marble is a metamorphosed type of limestone, it is naturally alkaline in quality. Thus, exposure to rain, which is naturally slightly acidic, or any other acidic substance (for example, hydrochloric acid mistakenly intended to clean the stone) will cause marble to granulate and “sugar” over time. An extreme example of marble deterioration can be found in St. Joseph’s Cemetery No. 1. The failure that likely occurred with this stone was related to moisture entrapment within the tomb itself. This, paired with the tight, compressive position of the tablet within the opening, caused the closure tablet to bow and “bubble” outward.

One of the most noticeable granite tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is that of stonecutter and sexton James Hagan. This remarkable tomb was built of red-colored Scotch granite in 1872. Around the same time, Hagan also constructed the monument of Governor Henry Allen, which was also located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 until it was moved to the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the 1880s. This monument, too, was carved from Scotch granite.[24]

[1] Louisiana Geological Survey, Geology and Agriculture: A Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1902), 133-134.

[2] National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Northeast Region, Architectural Preservation Division, The Washington Monument: A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2005), 28. “Washington National Monument,” The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 22, 1850, page 1. The stone is referred to as “freestone,” meaning a soft, friable sedimentary stone. [3] Graham R. Thompson and Jonathan Turk, Introduction to Physical Geology (Rochester, NY: Saunders College Publishers, 1998), 133-137. Slate headstones are found commonly in the Northeast dating to the colonial period. Slate headstones are also present in cemeteries as far south as Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. However, no slate headstones are visible in the cemetery landscapes of New Orleans. [4] Mary Louise Christovich, Roulhac Toledano, and Betsy Swanson, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. I: The American Sector (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 1998), 57. [5] Daily Picayune, September 27, 1850, 2; Daily Picayune, May 2, 1853, 1; Daily Picayune, February 28, 1869, 11. [6] “Alexander Hill, Welsh and American Slates, Slabs, etc.” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 4, 1875, 6. These slates priced from $6.50 to $10 per square; “Slates! Slates! Slates!” Ouachita Telegraph (Monroe, LA), July 22, 1872, 2. [7] “Brig Casket arrives from New York with sundry marble slabs,” Louisiana Advertiser, April 29, 1820, 3. “Barelli & Company, commission merchants, selling blocks of Italian marble,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1845, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 10, 1848, 7; Daily Picayune, February 17, 1848, 3; Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1851 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1851), page AT. [9] Edwards’ Annual Director to the Inhabitants, Institutions….etc., etc., in the City of New Orleans for 1871 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1870), 275; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [10] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. [11] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8. [12] “Alabama Marble,” Daily Picayune, October 1, 1845, page 2; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [13] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. In this year, cost to transport Alabama marble to New Orleans was 32 cents per cubic foot. [14] Leonard V. Huber et. al. New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 54-55. [15] Vermont Railroad Commissioner, Eleventh Biennial Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of Vermont (St. Albans, VT: St. Albans Messenger Co., 1908), 308. [16] Daily Picayune, July 15, 1853, page1; Daily Picayune, June 16, 1855, 1. [17] Thomas Nelson Dale, The Commercial Marbles of Western Vermont (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 117-122. [18] Tariff Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means, Second Session, Fifty-Fourth Congress, 1896-97, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 275-279; “Random Notes,” The Reporter: The First and Only Journal Published in the World Devoted Exclusively to Granite and Marble, No. 1 (January, 1900): 33. [19] David Spence Hill, Industry and Education: Part Two of a Vocational Survey for Isaac Delgado Central Trades School (New Orleans: The Commission Council, 1916), 227. [20] “Science and Industry,” The Colfax Chronicle (Colfax, LA), November 3, 1888, 3. This was not an uncommon claim for many quarries to make. “Georgia Quarries,” The True Democrat (Bayou Sara, LA), January 30, 1897, 7. [21] Memoirs of Georgia, Vol. I (Atlanta: The Southern Historical Association, 1895), 211-217. [22] A. Oakley Hall, “Cities of the Dead,” in Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers Tales and Literary Journeys, Frank de Caro, editor. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998), 532-533; Arthur Wellington Brayley, History of the Granite Industry of New England, Volume I (Boston: National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913), 114. [23] Ibid., 84. [24] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley of Durham University, UK, for his knowledge and expertise in identifying the Hagan tomb as Scottish granite. [25] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1895), 1095. [26] “Notes from the Quarries,” Stone: an Illustrated Magazine Vol. 4 (1892): 496.

17 Comments

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly