|

Final part in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. November 1945: six months after victory in Europe and three months since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In New Orleans as much as elsewhere, communities recovered from four years of total war. In the weeks leading up to All Saints’ Day, preparations for those who died overseas was a topic of discussion. Many of these soldiers would not come home at all. The American Battle Monuments Commission, which had been founded in 1923, would establish fifteen foreign monuments and cemeteries in Europe, the Pacific, and Tunisia to memorialize fallen soldiers. In April of 1945, the war department announced 5,335,500 newly available burial plots in 79 existing and new cemeteries.[1] This number seems enormous until we remember that 16.1 million Americans served in World War II. About 300,000 died in service.

As early as mid-October 1945, hardware stores advertised items specifically for tomb care, including “Rock-Tite cement paint, which…is waterproof, tends to seal tomb corners, and lasts for years.” In many cases these materials were ultimately harmful to soft lime-stucco and brick tombs. Yet 1945 heralded a long (and ongoing) boom of new, strong, and user-friendly materials that would widely be seen in New Orleans cemeteries. This technological and cultural boom contrasted with some of the oldest cemeteries in the city, which were seen as outdated and, at worst, nuisances. Such was the case for Girod Street Cemetery. The Protestant cemetery, founded in 1822, had long been considered an eyesore. As early as the 1880s, the state government of Louisiana considered closing the low-lying cemetery altogether. By the 1940s, its condition was such that cemetery authorities took action. In 1945, officials at Christ Church Cathedral conducted a survey of Girod Street – “the first Protestant burial ground in the Lower Mississippi Valley" – and concluded that “some 1000 of the old vaults and tombs in which many of the city’s prominent and wealthy families were buried are a menace to public health.[4]” Each of these vaults and tombs was marked on All Saints’ Day 1945, and posted with a notice to families that the tombs must be repaired within 60 days. If no action was taken, said the city public health department, the tombs must be demolished. Reports from the sexton of Girod Street Cemetery suggested that as many as forty families did respond to the notices. However, it was too late for Girod Street Cemetery. The burial ground was deconsecrated in 1957 and demolished. The remains of white bodies were re-interred in Hope Mausoleum, and burials of African Americans were interred at Providence Memorial Park. [1] “Move to Return War Dead Begun,” Times-Picayune, April 5, 1945, 27.

[2] “Orleanians Plan Halloween Observance in Usual Style,” Times-Picayune, October 31, 1945, 4. [3] “Up and Down the Street,” Times-Picayune, October 11, 1945, 34. [4] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945, 12; “Girod Cemetery Inspected,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945, 5.

3 Comments

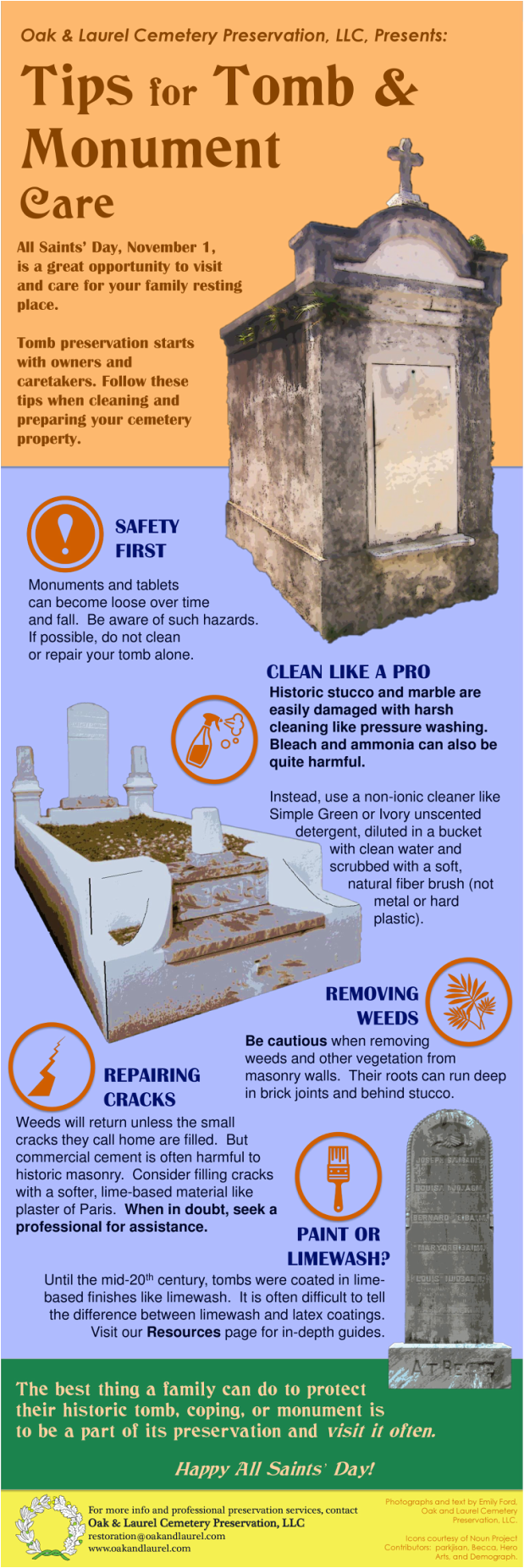

As All Saints' Day approaches, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC would like to share some preservation-friendly tips for tomb and monument cleaning, care, and repair.

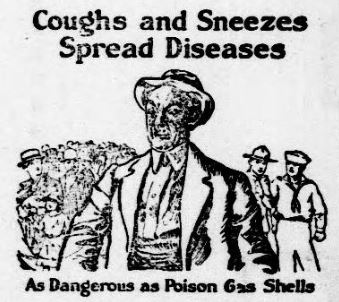

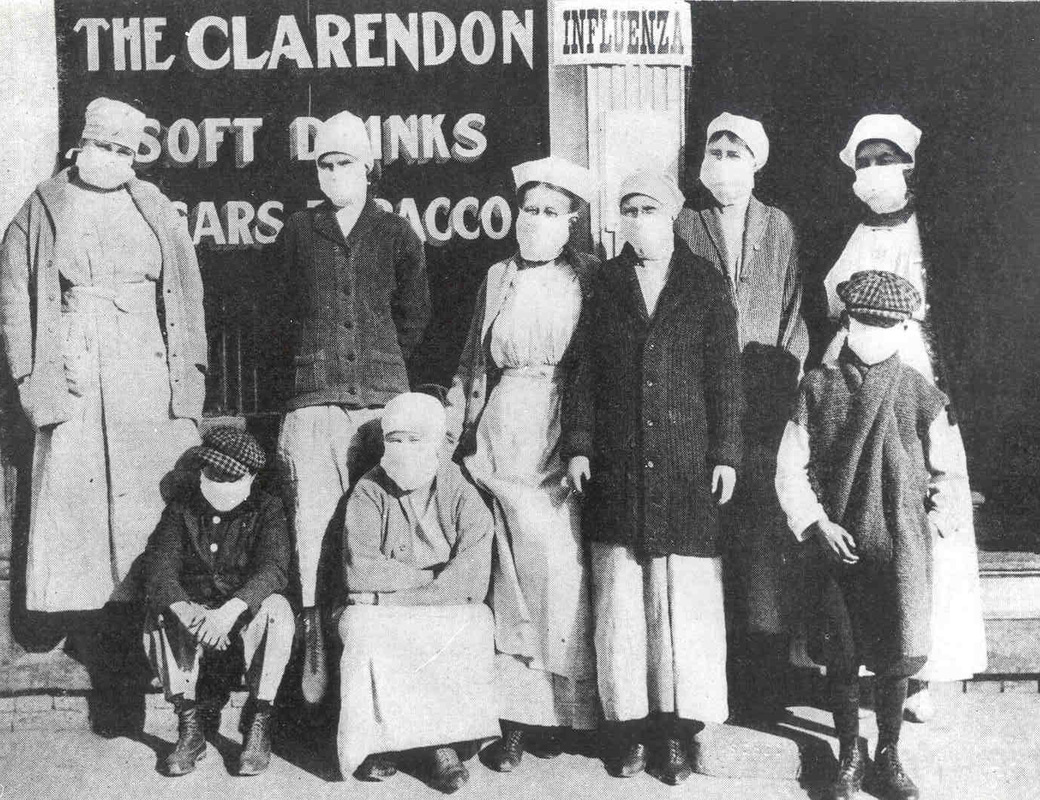

If you are a cemetery property owner, there are so many things you can do to help your tomb or monument last for generations. These are just some basics. As always, visit our Resources page for videos, articles, and other more in-depth information, or Contact Us for guidance with your specific tomb property. If you are ever in doubt, ask a preservationist! Fourth in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. New Orleans, along with the rest of the United States, was at war. The drafts of 1917 and 1918 would send a total of 71,000 officers and enlisted men from Louisiana to Europe to fight in World War I. On the home front, military installations were built, war bonds were purchased, and the economy boomed to meet new agricultural and industrial demands. In May 1918, Berlin Street in New Orleans was re-named General Pershing as a patriotic gesture.[1] Although many of the dark realities of trench warfare in Europe had yet to touch New Orleaneans, some families had already felt the pain of loss. Grayson Hewitt Brown, only nineteen years old, was stationed at Camp Beauregard near Pineville. A volunteer to the 141st Field Artillery, Brown assisted health care workers during an outbreak of spinal meningitis by carrying a stricken comrade out of the camp. Days later he died of the same disease. His parents buried him in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 along the main aisle with the epitaph, “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends.[2]” But the Great War was only one of two world-wide battles in 1918. The great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 swept across the globe in three waves, the most pronounced of which had only begun to wane by November. Indeed, many of the young men drafted to the military in this year died of influenza before even reaching the trenches. Such was the case for Henry Philip Walter Rathke, not even 26 years old, who died in naval service in New York prior to deploying. He was also buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; he left a widow and a young daughter.[3]

Supply of the flowers had been thinned already by families mourning those died of influenza. By late October, chrysanthemums were advertised at $6 to $9 – $100 to $150 in present-day dollars – and sold at twice the price of roses.[5] The chrysanthemum blight was front page news, and florists noted that customers were purchasing red roses and dahlias, as opposed to the usual “dead white.” In the next year, a third and final wave of influenza would cross the United States, as Louisiana’s enlisted men returned home from war. In 1921, a bronze flagpole was erected in Audubon Park to commemorate New Orleans Great War veterans. Yet the commemoration of those lost to war and influenza took place also in the decoration of graves on All Saints’ Days in years to come.  "The floral world will not be outdone by human beings, it would appear, and is plunged in the midst of one of the most widespread outbreaks of disease in history of local greenhouses... following out the example of human beings as closely as possible," from the Times-Picayune, Oct. 27, 1918. Image Dodd, Mead and Company - New International Encyclopedia (1923), Wikimedia Commons. [1] The Weekly Iberian, May 11, 1918, 4.

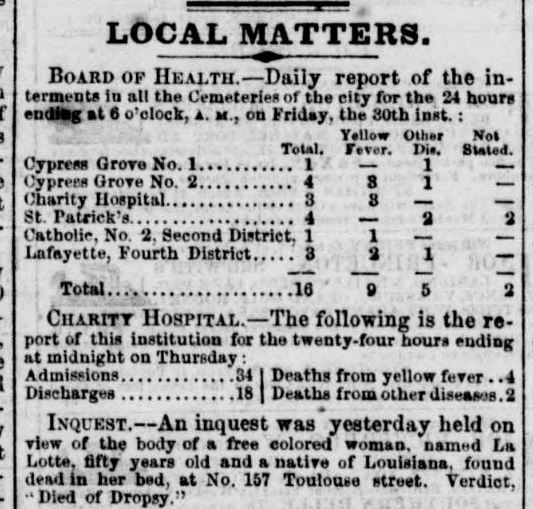

[2] “Grayson H. Brown Dies at Beauregard,” Times-Picayune, January 19, 1918, p. 11; “Armory Fund Gets Soldier’s Earnings,” Times-Picayune, August 24, 1918. [3] http://www.rainedin.net/silbern/i11310.htm [4] Natchitoches Enterprise, October 31, 1918, 3; Times Picayune, November 1, 1918, 10; St. Martinsville Weekly Messenger, October 26, 1918, 2. [5] Advertisement of Frank J. Reyes, florist, 525 Canal Street, Times-Picayune, October 20, 1918, 2; “Blight Attacks Chrysanthemum Crop of the City,” Times-Picayune, October 27, 1918, 1. The third in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. 23,707 infected. Not less than 4,600 dead. Such was the toll of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in New Orleans. The Crescent City was ground zero – the first point of contact in the United States for an epidemic that swelled north and eastward from July through November, taking 20,000 souls in total. Dozens of burials in each cemetery each day led one report to state that, in a sense, each day of the summer of 1878 had been All Saints’ Day. On the day of the holiday itself, many graves still retained the decorations of burial.[1] And the epidemic was not even completely over.

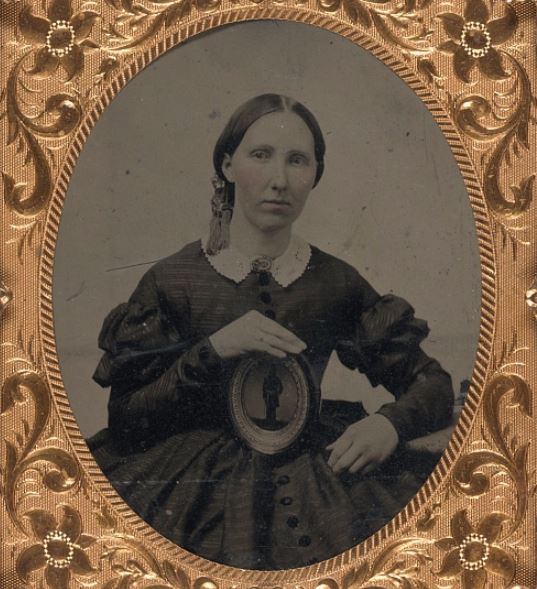

In the days leading up to All Saints’ Day, some health officials even cautioned against the yearly tradition of decorating and caring for loved ones’ graves. Said the Daily Picayune: It should be mentioned… that some physicians are of the opinion that, owing to the extraordinary number of interments during the summer and the prevalence of infectious disease, it would not be safe for a general decking of graves to be carried out as on occasions of the past.[2] The second in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. Need we say whose graves they were? Need we say whose fair hands placed those mementoes there, or whose kind hearts prompted the deed? On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, ending the Civil War. In New Orleans, infrastructure and economy lay in ruin. By November, the observance of All Saints’ Day was fundamentally changed from antebellum celebrations – in fact, the way all Americans interacted with death had changed forever. In general, nineteenth century Western culture was marked by an intimacy with death that would be incomprehensible to most modern-day people. Understanding that death could be swift and sudden, each person hoped only for a “good death” – one in which last words could be uttered, surrounded by loved ones. This ideal was sought even among soldiers, who kept letters in their pockets in case of their death, or who wrote such letters for dying friends. Yet the horrific realities of war – and the bad death that was its companion – were unavoidable. Advances in technology led to extensive photographs of Civil War battlefields, exposing civilians to the carnage of the conflict, and “stripping away much of the Victorian-era romance around warfare.”

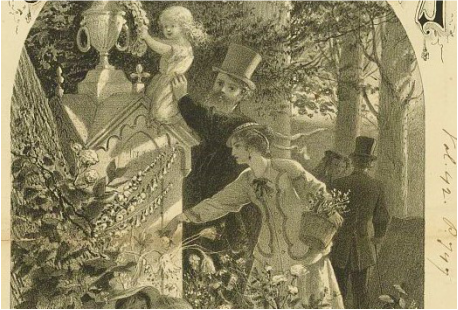

The destruction of the Southern economy in 1865 and 1866 is unlike anything any Americans ever experienced at any other time, at least on our home soil. The writers from Northern newspapers and magazines who went South after the war end up observing open coffins laying all over the place at cemeteries. They end up seeing old men and former slaves going around collecting bones because they could get a dollar for so many pounds of bones off battlefields. Those are the bones of men who died -- without a name, a place, they were never sent back to their families. This is what people would see if they went to those battlefields in 1865 and 1866 -- and for that matter for many years afterward. Most of the Civil War cemetery monuments we know today – the Confederate Army of the Tennessee and Army of Northern Virginia monuments, the Confederate monument at Greenwood Cemetery, the Grand Army of the Republic monument at Chalmette National Cemetery – were not erected until the 1870s and 1880s. In the years between Appomattox and the first official Memorial Day in 1868, efforts by Clara Barton and others to identify and re-locate fallen soldiers on both sides of the conflict resulted in the disinterment and reburial of thousands in New Orleans alone. However, this process would take years. On November 1, 1865, a great many of those who would come home were not yet located or reburied. Documents state that it was a beautiful Wednesday of extremely pleasant weather. Among the notable architecture newspapers chose to highlight in this year were the tomb of the New Lusitanos Benevolent Association and the tomb of W.W.S. Bliss, both located in now-demolished Girod Street Cemetery. They also noted the then-burial site of Albert Sidney Johnston in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. General Johnston was later re-interred in Texas: Several soldiers in tattered gray stood around. “You served under him,” we remarked to one, as we looked at him. Tears started in his eyes as he merely said, “yes,” and pulled a twig from a cedar circlet, hanging on the grave, and handed it to us. Other articles point out the noticeable presence of many more male attendees to ceremonies than in years past. Yet the focus of the holiday in 1865 seemed to be on the women – mothers and spouses who mourned lost soldiers. The Lusitanos tomb is described as attended by wailing women. In another account, women tend to the simple wooden monuments that temporarily marked their loved ones’ resting places: …we came upon a number of graves, very plain and unpretending, with but a wooden foot and head board… Not one was left undecorated – not a single one without a flower, a bouquet, or a wreath to mark that some kind, gentle, amiable feminine heart had stood there to tender a memento to departed valor. Need we say whose graves they were? Need we say whose fair hands placed those mementoes there, or whose kind hearts prompted the deed? They were the same heroic women of our city who, with noiseless step and sad, earnest eye, have treaded the avenues of the hospitals during the last four years, in search of the wounded and dying soldiers… Ten of them had assembled under a lofty oak… and spent almost the entire day in preparing wreaths and decorating those humble graves. Sources:

PBS American Experience: Death and the Civil War “The City,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1862, 1. Army of Northern Virginia tomb erected 1881; Army of the Tennessee tumulus erected 1887; Confederate Monument at Greenwood Cemetery, remains relocated 1868, monument erected 1872; Grand Army of the Republic monument completed 1883. “The City,” Daily Picayune, November 1, 1865, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1865, 1. Daily Picayune, November 5, 1865, 1. First in a five-part series of All Saints' Day through New Orleans history New Orleans heritage is steeped in holidays and celebrations. Amidst the hedonism and mystic antics of Mardi Gras, Twelfth Night, and other festivals is the contrasting solemnity of All Saints’ Day. Part of the Catholic calendar since the fifth century, All Saints’ Day (also known as the Feast of All Saints, Hallowmas, and All Hallows) has its origins in Roman, Germanic, and Celtic celebrations seated in prehistory. Today it is celebrated on November 1, although some Eastern Orthodox and Protestant denominations celebrate it on the first Sunday of November. The feast day began as a holy day in which the lives of the Catholic Saints were remembered and honored. However by the time of the arrival of French and Spanish colonists to New Orleans, the day rather signified the recognition of all saints, “known and unknown,” and more generally the remembrance and communal mourning of the dead by their survivors. By 1853, the oldest above-ground cemetery in New Orleans (St. Louis Cemetery No. 1) was 65 years old, and the imported traditions of above-ground burial and observance of All Saints’s Day enjoyed great significance in the rituals of the Catholic and Protestant communities. From the Catholic St. Louis Cemeteries to Protestant Girod Street, municipal Lafayette, and fraternal Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows’ Rest, the day was observed and reported on – not only as a day of mourning, but one of cultural spectacle, high style, and great charitable expectations.

From the numerous complaints made this morning of the careless manner in which the coffins containing dead bodies are left at the Fourth District cemeteries, it would appear that there are not enough hands employed there to bury the dead. The hearses bringing them place the coffins at the gate of the cemetery, and there, it is stated, numbers of them remain for hours, and in some cases all day and all night, the effluvia given forth reaching houses four and five squares off. … it is a sad enough necessity that we should live in the midst of an unsparing epidemic… But it should be the last reproach a city should receive, that she cannot bury her dead decently and respectably, in accordance with the feelings in which every human being participates.

The devastation of the epidemic lay not only in the cemeteries, but ever more so in the homes for widows and orphans. Benevolent associations, the members of which were bonded by nationality, profession, or religion, incorporated into All Saints’ Day a tradition of charity in which the orphans of various asylums would be present in the cemetery, collecting alms to support their care. Among these asylums was that of the Catholic orphan boys of the Third District, which cared for 300 children in October of 1853, and predicted another 100 within the next month. This institution, among others, stood present at the Catholic cemeteries on November 1, hoping for enough donations to build a new wing to accommodate their new charges.

The Daily Crescent describes a day of crowded cemetery avenues and people of all ages, “singularities of every hue, and representing every nationality… not before midnight were the decorations complete. It was then that thousand tapers and waxen lights everywhere covering the tombs were lit up, and a light flashed over the scene, imparting to it an almost magical brilliancy.” Said one author to the editors of the Baton Rouge Daily Comet of New Orleans’ All Saints’ Day observance: "Now, however, I am so much of a Catholic that I like all Saints day [sic] – I am in favor of the custom of making an annual pilgrimage to the graves of those we loved in life…” this author, signed only as “L,” describes the throngs of people, the “gaudy” decorations, the invocations of beautiful hymns. Yet the pall of epidemic’s devastation burns through even the most endearing recollections of All Saints’ Day 1853. “L.” concludes his letter not with the solemnity of honoring the dead, but with the discussion of the recent suicide of a New Orleans lawyer: He was buried on Sunday [October 30] followed to the grave by a large number of citizens. While the long cortege of carriages which followed his remains were passing slowly down the street to the Protestant Cemetery, another funeral came dashing along Hevia Street [now Lafayette Street], followed by a half dozen empty carriages, and all driven at a smart trot, as if in a hurry to get the dead out of sight as soon as possible. The latter procession had just time to cross the path of the former ere it came up making a forcible contrast in appearance and character between the two. One was a rich man going to lay down in his last resting place, the other was a poor stranger hurried to his final bed. When earth has reclaimed what was of her, who will be able to distinguish the ashes of the one from the other? Sources:

Walter Farquhar Hook, A Church Dictionary (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1852), 16. “Burying the Dead,” Daily Picayune, August 8, 1853, 1. “Female Orphan Asylum,” Daily Picayune, October 23, 1853, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 28, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 31, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, November 2, 1853, 1. “Correspondences,” Baton Rouge Weekly Comet, November 6, 1853, 1. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly