|

Published 144 years ago today in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, an interview with the assistant sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. It’s unclear how much of this article is speculative or fanciful, but in any case its content is fascinating. The article is presented here in pieces, with background inserted regarding the content. Original Times-Picayune narrative from July 13, 1873 is indicated in italics. Sitting on a Tombstone TALK WITH A GRAVEDIGGER --- “How long wil a man lie i’ the earth ere he rot?” [Hamlet] A reporter of the PICAYUNE, chancing in his peregrinations to stroll into the Washington Cemetery[1] in the cool of early morning, met and engaged in conversation with the assistant sexton. The term “sexton” is given to a person who maintains a cemetery in a professional capacity. It originated with a religious connotation, indicating a man who cared for both the church building and the adjoining cemetery. Later, as more and more cemeteries were established outside parish land, the term “sexton” migrated to the secular sphere. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as a municipal cemetery, and thus was never religiously affiliated. In 1873, the sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and 2 was Joseph F. Callico (1828 – 1885). Callico was a free person of color who worked for most of his career beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, and also beside fellow stonecutter Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. Around 1870, when Monsseaux himself ceased his business, Joseph Callico moved to Washington Avenue to serve as the sexton of the Washington Cemeteries. By 1875, he returned to St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, where his brother Fernand served as sexton.[2]

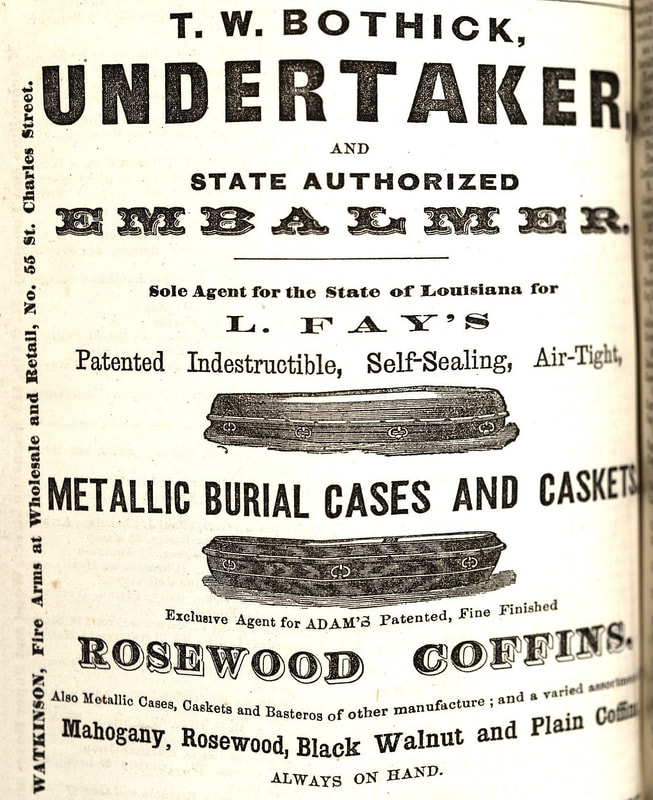

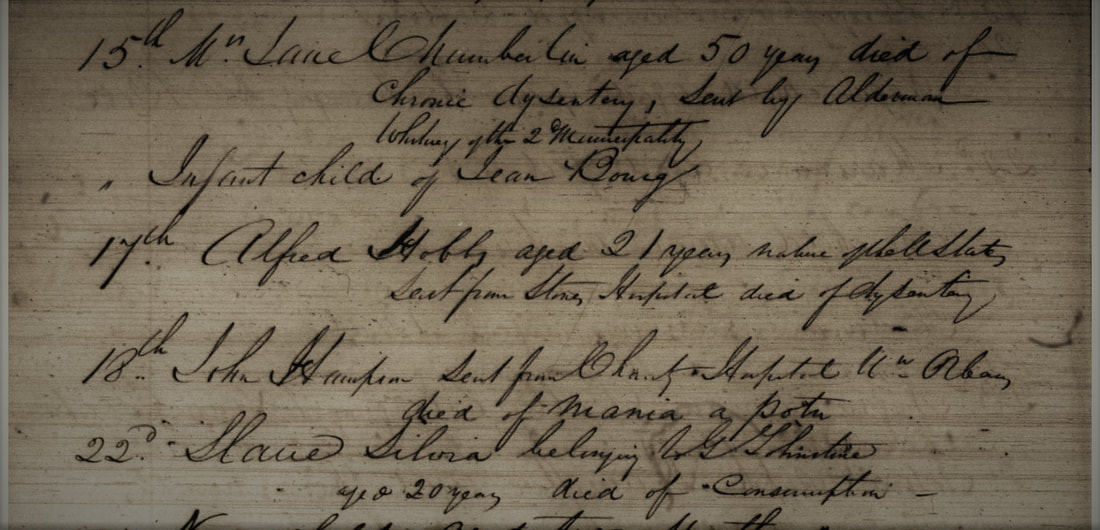

“Well, you know,” said the man, “there is a great difference in them. There are some here who, from their particular situation, keep much longer than others. There’s a man I came across the other day, digging a foundation for a tomb, who had been in the ground for two years, and he was in remarkably good condition. It is true, he was near the wall, and the drainage was good.” This passage offers some confirmation of what the landscape history of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 suggests: that earlier below-ground burials were replaced by above-ground tombs. Dr. Bennett Dowler wrote in 1852 that Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was a primarily a belowground cemetery, owing to the preference of Irish and German immigrants for inhumation over tomb burial.[4] Pre-1850’s burials in Lafayette No. 1 are difficult to find today, but most of which remain show some modification over time, suggesting that the assimilated children and grandchildren of immigrants later converted their family lots to traditional New Orleans tombs. This could be one reason the sexton came upon a burial while constructing a new tomb. The gravedigger expands on this notion in his next answer. “Do they bury many in the ground now in this cemetery?” “No,” said he “in this place most everyone has a tomb. You know, this yard has been buried some ten times over, and people don’t care to put their friends under earth when tombs don’t cost much more.” While “ten times over” may be exaggerated for Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in 1873, the cemetery was declared “full” by Lafayette and New Orleans city councils in 1847 and 1856, respectively.[5] Neither of these ordinances was paid much mind, and burials continued. Furthermore, in the earliest years of the cemetery, between 1833 and 1853, approximately 30% of the individuals listed in interment books are noted as enslaved people. Amounting to thousands if not tens of thousands of burials, records do not indicate their location, although they are unlikely to be in the cemetery wall vaults.[6]  Excerpt of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 interment books for August 1843. Over this week, burials included two deaths from dysentery, a twenty year old enslaved woman who died of consumption, and a death from "mania a potu," an historic term for alcohol-related illness, including delirium tremens. (New Orleans Public Library) From here both gravedigger and journalist get grim: “From your experience, what part of the body is the first to suffer from the effects of decomposition?” “The head goes first always. You see there isn’t so much flesh about it, and it doesn’t take long for it to go. The other parts go after it very soon; they all seem to go together.” While the good taste of asking this question in the first place is suspect, it is interesting to note the anachronism. In 1873, embalming had only recently become a possibility. The widespread practice of embalming starting in the twentieth century certainly affected the decomposition patterns of burials in New Orleans tombs and elsewhere. “In digging about these unoccupied places, do ever meet with the remains of human beings?” asked the reporter. “Oh, yes. The whole of Lafayette Cemetery has been filled, even to the avenues. When this was first a graveyard, it was not laid out regularly, and now when we have to repair the walkways, the bones are always turned up.” Prior to cement paving and other improvements that took place beginning in the 1940s, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1’s aisles were paved with crushed shells, marble pavers, and slate flagstones. Some of these paving materials remain visible. Archaeological test pits executed in the 1980s and 1990s indicated that crushed shells were regularly hauled into the cemetery to repave aisleways. This is likely the “repair to the walkways” the sexton mentions above. [more unnecessary description of decomposition] “Is there any difference between burying in the ovens and in the ground?” “Oh! Yes. In the ovens they don’t last six months, for with the metallic cases it does not take much time to destroy everything. In the ground, metallic cases, if they are good, last twenty years, and wooden ones about three."

"Yes! I have noticed that when they take on most they generally don’t come back to put flowers on the tomb much after the first month. “The widows come every week for about a month or two, fixing up everything. When they cry most they don’t come back at all, but when you see one who looks all the time at the coffin and doesn’t make a fuss you can be sure she will put flowers there for years.”

[1] Historically, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is frequently referred to as “the Washington Cemetery.”

[2] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84, 40; Edwards Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1872), 86; Edwards Annual Directory for New Orleans 1873 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1873), 90; United States Census, 1880, New Orleans, Louisiana, Roll 461, Page 234C. [3] “All Saints’ Day – The Living Remember the Dead,” Times-Picayune, November 2, 1873, 1. [4] Bennet Dowler, M.D., “Tableaux, Geographical, Commercial, Geological and Sanitary of New Orleans,” printed in Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1852 (New Orleans: Office of the Daily Delta, 1852), 21. [5] Mayoralty of New Orleans, Common Council, City of New Orleans, “An Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4. [6] New Orleans Public Library, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Interment Records, Vols. 1-5, microfilm. [7] Dowler, 21.

9 Comments

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly