|

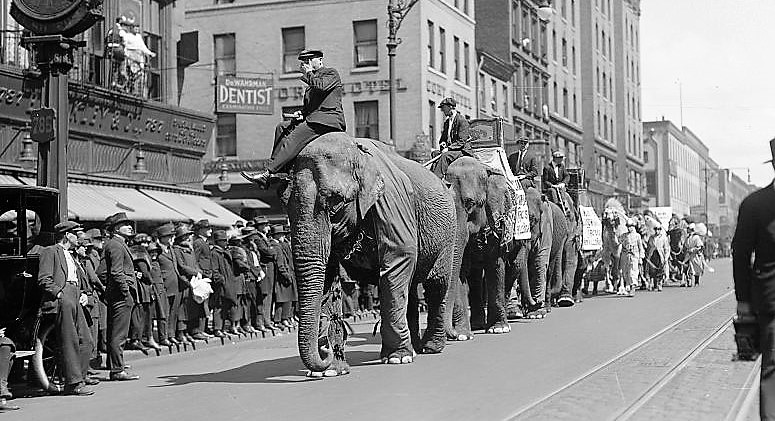

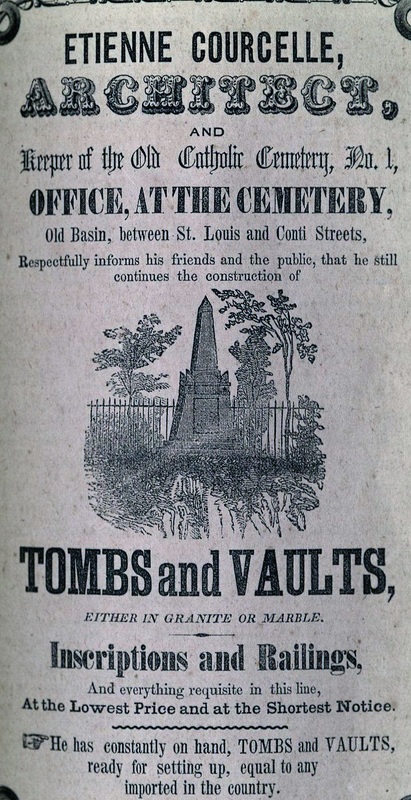

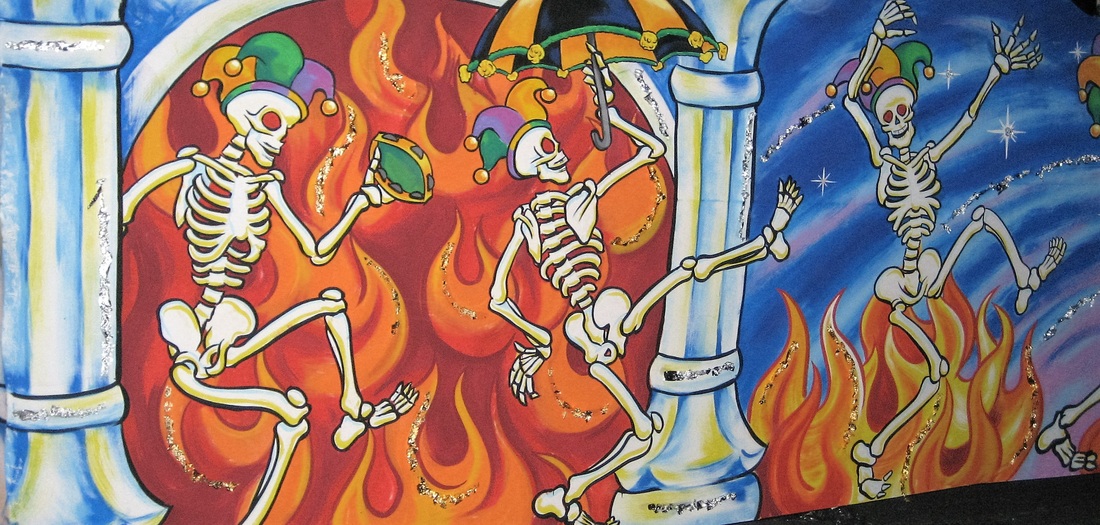

Over the past week, New Orleaneans have been treated to nightly parades in neighborhoods Uptown and downtown, on the West Bank and in Metairie. Today, Krewe of Thoth will ride down St. Charles Avenue, followed by Bacchus and others this evening. The fever pitch of Mardi Gras is upon us, culminating on Fat Tuesday, Mardi Gras Day. In the spirit of the season, we’ve mused on the place of cemeteries in Mardi Gras traditions – from the last resting places of Dead Rexes to the incorporation of death and cemeteries in costuming and floats. Seldom do Mardi Gras celebrations themselves take place in New Orleans cemeteries. But once or twice in a blue moon, amidst Storyville revelry or between the pages of a Gayarré novel, such things have happened. Today, on this Sunday before Mardi Gras, we explore the few instances of Mardi Gras dancing on the graves. The St. Louis Cemetery Marchers In one of the St. Louis Cemeteries, the dead were entertained by an especially satirical parade in 1911, when maskers dressed as deceased voters processed through the cemetery gates to follow the tail of the parade of Rex. The details of this event are discussed in two New Orleans histories, although primary accounts of the parade are scant. In what James Gill refers to as one of the “drollest examples” of political satire in Mardi Gras parades, marchers dressed as skeletons emerged from the cemetery holding signs marked, “Count me in for several votes,” “I’ll be with you on election day,” and “Dead, but still a voter.”[1] According to Buddy Stall’s New Orleans, the marchers labeled themselves “The Graveyard Pleasure Club,” “Girod Cemetery Voters League,” and “the Tombstone Brigade.”[2] The members of the St. Louis Cemetery Marchers were anonymous, although one marcher later revealed his identity to be Edouard F. Henriques, a local judge. He and other members were members of the Good Government League, part of the Progressive movement in Louisiana and, in the next year, supporters of “Bull Moose” presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt, much against the dominant Democratic "machine" in New Orleans. The Marchers emerged from St. Louis Cemetery (presumably No. 1, or possibly No. 2) after having “entertained the sexton” with their antics. They caught up to Rex and followed along its route, as one parade-goer remarked, “Their silent message is more meaningful than any spoken word I can imagine.” They continued behind the parade until police forces peacefully disbanded them, just before they reached City Hall. The Elks Burlesque Circus In the days leading up to the St. Louis Cemetery Marchers 1911 procession, a bigger, louder ruckus was taking place just blocks away. At Elks Place and Canal Street, a great circus would take place, complete with lion tamers, elephants, and acrobats. On the Friday before Mardi Gras, this circus paraded through the city, marching uptown as far as Felicity Street, and back through the Central Business District.[3] The enormous circus and parade were organized by the New Orleans Lodge No. 30, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, known casually as the Elks Lodge, and for whom Elks Place is named. If you live in New Orleans, you probably know them for their tomb, which looks out on the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The 1911 circus and parade, complete with a petting zoo of baby elks, was held as a fundraiser for an imposing tomb the Elks Lodge hoped to construct in Greenwood Cemetery. Elks members costumed as clowns and even traveled abroad to learn how to care for circus animals – said one article, “Quite a number of the antlered herd are taking corresponding lessons on how to manage elephants and camels.[4] The big top Mardi Gras-season fundraiser was as ambitious as the organization’s tomb plans. The Elks Lodge memorial is a tumulus: a burial chamber which has been covered in earth, making it resemble a hill or burial mound. While New Orleans is no stranger to tumuli – at one point in time, they were quite common in cemetery landscapes – the Elks Lodge tumulus is one of the most iconic of these structures in American cemeteries. The tumulus was constructed by Albert Weiblen at the cost of $10,000 – essentially $250,000 in 2016 dollars.[5] Its subterranean walls were topped with a giant boulder of Alabama granite, on top of which a nine-foot-tall bronze elk was erected. Two years and some minor (but noticeable) foundational issues later, the cemetery landmark was completed. Today, organizations with communal tombs and society burial places often find great difficulty in raising the capital needed to restore their deteriorating cemetery property. Perhaps it’s time once again to bring the circus to town for the benefit of our historic cemeteries. Tintin Calandro: The Mad Musician of the St. Louis Cemetery Our final Mardi Gras cemetery story is exactly that: a story. On this blog, we like to keep things factual, but in the spirit of the prankishness and surreality of Carnival, we recall the tale of Tintin Calandro. Celebrated New Orleans author Charles Gayarré (1805 – 1895) is memorialized in the city as its premiere 19th century historian. A beautiful terra-cotta memorial to him sits at the divergence of Esplanade Avenue and Bayou Road. He is best remembered for his History of Louisiana (1866), but he did write two novels as well, Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction (1872) and Aubert Dubayet (1882). Featured in both of these novels is Augustine Calandrano, more frequently referred to by the narrator as Tintin Calandro, French revolutionary exile, talented violin player, and eccentric sexton of St. Louis Cemetery. In Fernando de Lemos, Tintin Calandro is a “genius of madness,” each night serenading his ghostly charges:

Calandro and Fernando de Lemos have a special relationship in which they spend nights in the cemetery, discussing philosophy, love, ethics, and other profound topics amidst the tombs. Toward the end of Calandro’s life, it appears his fits of insanity worsened. Nearing his own death, the old sexton fought frailty and his better senses in order to go to the cemetery for a final concert, on Shrove Tuesday: He said that the ghosts were going to have a Mardi Gras ball and he wanted to open the event by playing an overture, after which an orchestra of spirits would supply the music… [the narrator] accompanied the musician to the cemetery. There Tintin greeted the ghosts, bade them be silent and seated, and then seating himself and his companion on a tombstone, he began to play. … In the spell which overcame him he saw the ghosts whisking past in the dance, and the mad excitement grew upon him until the sound of the violin was hushed. Then Tintin apologized to his visionary audience, and allowed his friend to escort him home.

[1] James Gill, Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans (University Press of Mississippi: 1997), 166.

[2] Buddy Stall, Buddy Stall’s New Orleans (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1990), 167-169. [3] “Elks Announce Route of Parade Preceding Burlesque Circus,” Daily Picayune, February 20, 1911, p. 2. [4] “Elks’ Circus to be a Feature During Carnival Week Here: Parade and Performances to be Filled with Features Farcy, Freakish and Funny,” Daily Picayune, January 15, 1911, 30; “Circus Catches: Pokorny’s Little Elks Arrive for Big Show,” Daily Picayune, February 17, 1911, 7. [5] “Elks’ Tomb to be Erected on Fine Greenwood Cemetery Site,” Daily Picayune, August 7, 1911, 7. [6] Excerpt from Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction, featured in The Southern Bivouac, Vol. II, No. 1 (June, 1886), 112-114; James A. Kaser, The New Orleans of Fiction: A Research Guide (Scarecrow Press: 2014), 92. [7] “Tintin Calandro: Judge Gayarré Tells the Story of the Mad Musician of St. Louis Cemetery,” Oachita Telegraph, January 20, 1887, 1.

1 Comment

Carnival traditions like Mardi Gras and its Old World predecessors originate in Catholic pre-Lenten traditions and even pre-Catholic pagan traditions, each of which focused on the reversal of social and class roles, enjoyment of the senses, and indulgence in the face of repentance and self-denial (be that in the form of the Lenten tradition or the last months of winter without fresh meat and vegetables). In both ancient and modern contexts, Carnival is traditionally a time of celebration of life, focusing on earthly delights in the face of mortality. Yet despite these overarching themes, death and cemeteries still creep in. Beginning in Europe and later thriving in New Orleans, death has a habit of crashing Mardi Gras parties. The Triumph of Death in Florence In 1930, the Times-Picayune related an age-old story of one of the most famous appearances of Death at Carnival, in Florence, Italy, in the early 1500s: Then, suddenly, there came in sight a fiery procession, every member of which carried a torch. Under the torch flame it could be seen that every rider wore a death’s head and a black shroud. The death’s march came closer, and the horrified spectators saw that halfway down the line of parade was a covered cart drawn by four oxen, all four hung with black cloths painted with skulls and crossbones… On a pedestal in the center of the roof [of the float] stood the figure of Death, with the light the torches streaming through his hollow eye-sockets and empty ribs, and in his hand his scythe. At his feet lay six open coffins, within which could be seen six bodies wrapped in shrouds… When the procession reached the public square the skeleton attendants blew a trumped blast, and the shroud-wrapped bodies stood up in the coffins and chanted: “As ye see us, dead we be; Dead like us, ye we’ll see; We have been just as ye, Ye shall be just as we.”[1]

The famous Triumph of Death parade occurred in either 1511 or 1512 – one account states 1506 – and was engineered by the painter Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522). Di Cosimo was recently referred to as “the strangest master of the Florentine Renaissance,” by an author that counted the Triumph of Death parade as one of his accomplishments. Most of this history of di Cosimo’s life comes from 16th century artist and historian Giorio Vasari. Vasari’s account of the parade describes a car (float) decorated by di Cosimo to appear as “a mobile cemetery,” from which the costumed dead would spring from either tombs or caskets, and sing to the spectators of their inevitable mortality. The procession was “designed to terrify, but it also provided shock value and gruesome entertainment.[2]”

Although 1506-1512 represented a lull in the ever-occurring waves of Black Plague epidemics, the presence of death was never too far from the Florentine consciousness. Piero di Cosimo himself is assumed to have died of plague in 1522. That the Times-Picayune revived this four century-old tale for Mardi Gras 1930 is not entirely surprising. By this time, death was already marching in the parade. Beyond a strange 1911 incident in which a parade actually took place in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 (to be discussed in our next blog post), the ranks of Mardi Gras Indians had already, by this time, included a tribe of ghostly marchers. Deathly Maskers The North Side Skull and Bones Gang has its origins in the early 19th century and developed in the early 20th century alongside other African American Mardi Gras traditions like the Baby Dolls and Mardi Gras Indians. In a tradition that continues today, members of the North Side Skull and Bones Gang wake up before dawn on Mardi Gras day and parade from the Backstreet Cultural Museum through the Tremé neighborhood ringing bells, shaking rattles and shouting, dressed as skeletons. Much like the Renaissance parade of Florence, the North Side Skull and Bones Gang reminds us all that “death is always lurking, and sooner or later, it will come knocking at your door.”

The Skeleton Krewe marches on Mardi Gras day down St. Charles Avenue and into the French Quarter. This interview by photographer Julie Dermansky with Skeleton Krewe founder Christopher Kirsch describes the history of the Krewe of black-clad skeletons with enormous papier-maché skull masks. In its classical purpose as a time of celebration and role reversals, Mardi Gras is a time where anyone can be anything they want to be. New Orleans’ great tradition of costuming emerges in full force, and the expression of so many human experiences bursts forth – be it in the form of vivacious parades or celebrations of death. From Renaissance Italy to the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, the grim reaper has frequently had a place at the parade. And dressing as a New Orleans tomb for Mardi Gras? Apparently, that too has been done. Next time we visit New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras traditions, we look at times when the party entered the cemeteries themselves – the St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 Marching Club, and a mad cemetery caretaker. [1] “Mardi Gras Joke Once Placed Ban on Night Parades: Comus Carries on Despite Florentines’ Strange Sense of Humor,” Times-Picayune, February 2, 1930, p. 28.

[2] Landon, William J., Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi and Niccolo Machiavelli: Patron, Client, and the Pistola fatta per la peste (University of Toronto Press, 2013) 49-52. During Mardi Gras season, New Orleans sees increased tourist traffic to one of its most popular attractions: its cemeteries, particularly Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. It nearly seems counterintuitive to visit a place of death and remembrance on a trip so populated with mirth and celebration. Yet the relationship of New Orleans cemeteries to its carnival celebrations is much richer than simply beads on wrought iron or the odd Muses shoe left on a tomb shelf. While the Carnival celebration is one of life and vivacity, the themes of mortality and cemeteries often creep into the mix. From death-themed floats, krewes, and costumes to actual celebrations in the cemeteries themselves, our cities of the dead have been part of the Mardi Gras stage since the 19th century.

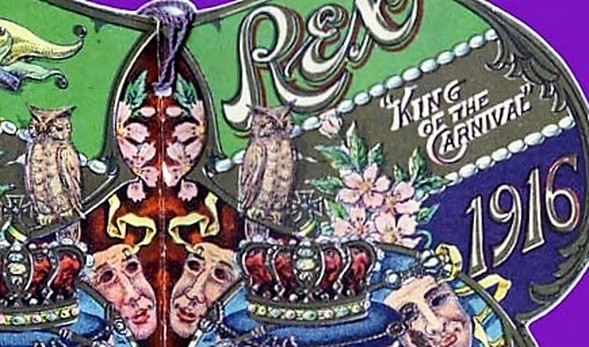

The first (and last) Jewish man to serve as Rex in New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, Salomon later moved to New York, although he visited New Orleans each year for Mardi Gras for decades after his reign. He died in 1925 and, surprisingly, it appears as if no one knows where he was buried. His final resting place seems to remain a mystery. His sister Delia, however, married local liquor dealer Otto Karstendiek and, upon her death in 1866, was buried in the only cast-iron tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Lewis Salomon was remembered as the first Rex for decades after his great parade. And although his final resting place may remain a mystery, it stands to reason that it does, in fact, exist someplace. Unfortunately, neither of these things were true for the third King of Carnival, Rex 1874, A.W. Merriam.

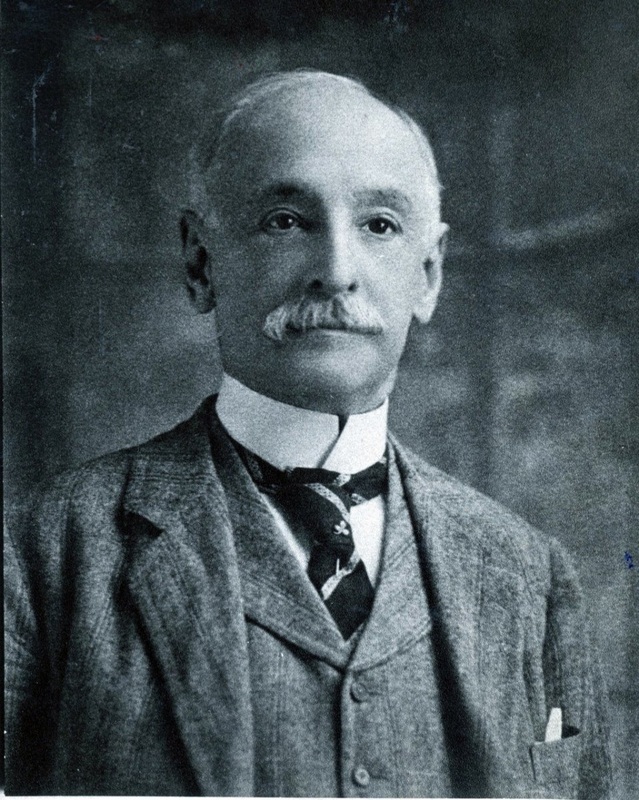

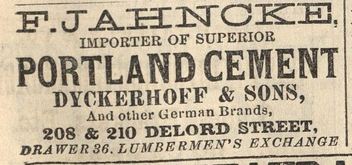

Merriam’s funeral was held days later and, in an even more tragic turn of fortune, his moral remains were paraded to Girod Street Cemetery, where he was interred.[1] While the old king may have rested in peace for as long as seventy years, Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957. Whether the remains of A.W. Merriam were transferred to Hope Mausoleum (as all unclaimed remains of white people reportedly were) or elsewhere, or at all, is anyone’s guess. No record concerning Girod Street Cemetery includes his name. Rex rules his chaotic kingdom for a day. He is emblematic of both disarray and refinement, satire and grace. Upon the close of the evening on Shrove Tuesday, when Rex has met with the Court of Comus and the curtain is drawn on the season, Rex relinquishes his rule until next year, when he returns in the guise of another man. For most of those who served as Rex, death and burial was a rather uneventful affair. Yet one King of Carnival would have a much greater impact on the cemeteries of New Orleans than simply being buried there. The Builder King In 1915, Mardi Gras took place on February 16. Rex this year was Ernest Lee Jahncke, who “headed the procession on a golden chariot of state symbolic of his imperial power… crowned with jewels and wearing a mantle of cloth of gold, [sitting] upon the throne in the center of the car, gracefully acknowledging the plaudits of his subjects.” The theme that year was “Fragments from Sound and Story,” and featured such floats as “The Fatal Kiss of Undine (the water nymph)” and “The Barter of Mephistopheles,” illustrating the bargain of Dr. Faust with the devil.[2] Rear Admiral (USNR) Ernest L. Jahncke (1878-1960) served as assistant secretary of the Navy from 1929 to 1933 and was himself a “renowned yachtsman.[3]” He was the son of Fritz Jahncke (1847-1911), a German immigrant and founder of Jahncke Navigation Company. The elder Jahncke was instrumental in one of the greatest shifts in tomb construction in New Orleans history. Beginning in 1879, Jahncke was one of the first building supply dealers to make Portland cement available for his clients. While Portland cement had been available elsewhere in the country as early as the 1860s, its use was nearly unheard of in New Orleans prior to Jahncke’s business. Since the 1700s, builders in New Orleans cemeteries used mortars, stuccoes, and renders mixed from hydrated lime, a material procured from burning limestone or oyster shells in a kiln. These materials required protection from the elements, usually achieved by limewashing tombs on a regular basis.

The materials which Fritz Jahncke had made available to New Orleans cemetery builders would eventually replace lime-based stuccoes and shift the way tombs were constructed. Just as importantly, Jahncke established himself as a great paver, paving sidewalks and streets using new cement mixes and replacing the brick and shell-lined avenues that once marked neighborhoods and cemeteries. These materials in cemeteries cut down on the need to mow grass or perform other landscaping. An unintentional consequence of this paving process was the exacerbation of drainage issues in cemeteries which continue to this day. The Jahncke family expanded from serving as Mardi Gras royalty a century ago to owning a shipyard and a dry dock in addition to the cement company. Ernest continued these businesses into the twentieth century and long after his reign as Rex. He was, however, the Rex spokesperson who, in 1942, announced that Mardi Gras would be cancelled that year in the spirit of solemnity and frugality in the face of World War II. Both Ernest and Fritz Jahncke are buried in Metairie Cemetery. In the next installment of our examination of New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras history, we bring death to the party itself and check out cemetery and mortality-themed floats, krewes, and costumes.

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly