|

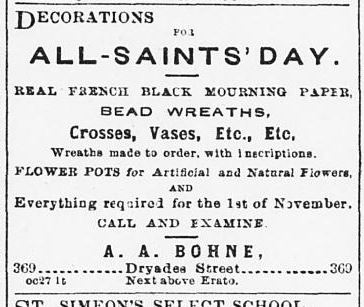

The third in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. 23,707 infected. Not less than 4,600 dead. Such was the toll of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in New Orleans. The Crescent City was ground zero – the first point of contact in the United States for an epidemic that swelled north and eastward from July through November, taking 20,000 souls in total. Dozens of burials in each cemetery each day led one report to state that, in a sense, each day of the summer of 1878 had been All Saints’ Day. On the day of the holiday itself, many graves still retained the decorations of burial.[1] And the epidemic was not even completely over. In the days leading up to All Saints’ Day, some health officials even cautioned against the yearly tradition of decorating and caring for loved ones’ graves. Said the Daily Picayune: It should be mentioned… that some physicians are of the opinion that, owing to the extraordinary number of interments during the summer and the prevalence of infectious disease, it would not be safe for a general decking of graves to be carried out as on occasions of the past.[2]

In most cemeteries, vendors set up outside the gates, selling flowers, candies, and confections. One report notes a woman erecting an outdoor kitchen, selling hot soups to passing mourners. November 1, 1878 was the first All Saints’ Day after an epidemic that completely changed the face of many New Orleans cemeteries. Descriptions of the day paint a cemetery landscape that was irreversibly altered, and yet also completely lost to our eyes in the 21st century. In Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, entire sections of the cemetery had been demolished for the construction of new tombs to accommodate the dead. The constant attention to the cemeteries required in times of epidemic led to new structures, more landscaping, and a greater investment in their care and expansion. Below are the descriptions of selected cemeteries from November 1, 1878 paired with images of their present-day landscapes. The layers of years and variations in use are remarkable. St. Vincent de Paul (Louisa Street) This cemetery is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful in New Orleans… Visitors there will become enamored with death. Roses and violets, cypresses and mournful pines adorn the sad scene, contending with each other for supremacy. There the soft magnolias blow, and by the side of an humble grave with a white marble slab, magnificent mausoleums can be seen, of which Queen Artemisia would be proud. The Daily Democrat also notes that St. Vincent de Paul opened a five-acre Potter’s Field in 1878. It is unclear where this was once located. St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 The grand old monument to the Cazadores de Orleans being almost hidden from view by two immense flags draped with the insignia of mourning… It is in this cemetery also that are erected many of the costliest private tombs in the city… but singularly enough, these tombs of the rich in not a few instances were not decorated with even a single flower or token of remembrance of any kind. This apparent neglect was probably due to the fact that the owners of the majority of these tombs are still absent from the city on account of the epidemic. St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 (“The New St. Louis Cemetery”) … was visited by many thousands of people during the day, many of whom expressed audibly their admiration for the magnificent row of oaks of the main alley, three quarters of a mile long… Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 1 The Potter’s Field had no immortelles. The old fence supported no bouquets of flowers… Row after row ran these beds of quiet and ease to the tired. The suicide slept quietly beside the maniac, the waif beside the fallen merchant… No visitors crowded the narrow paths between the long rows of graves, and not a foot disturbed the old coffin lids lying athwart the alleys. Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 1 is now the site of the Katrina Memorial Cemetery. Learn more here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly