|

Final part in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. November 1945: six months after victory in Europe and three months since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In New Orleans as much as elsewhere, communities recovered from four years of total war. In the weeks leading up to All Saints’ Day, preparations for those who died overseas was a topic of discussion. Many of these soldiers would not come home at all. The American Battle Monuments Commission, which had been founded in 1923, would establish fifteen foreign monuments and cemeteries in Europe, the Pacific, and Tunisia to memorialize fallen soldiers. In April of 1945, the war department announced 5,335,500 newly available burial plots in 79 existing and new cemeteries.[1] This number seems enormous until we remember that 16.1 million Americans served in World War II. About 300,000 died in service.

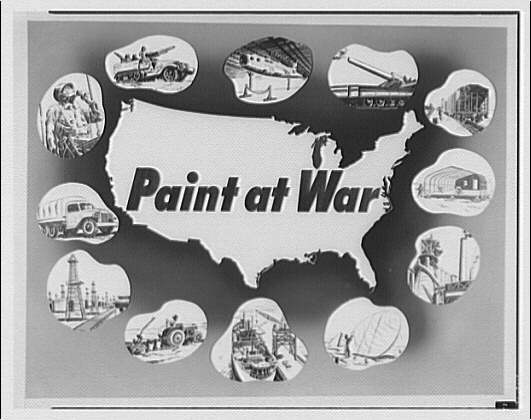

As early as mid-October 1945, hardware stores advertised items specifically for tomb care, including “Rock-Tite cement paint, which…is waterproof, tends to seal tomb corners, and lasts for years.” In many cases these materials were ultimately harmful to soft lime-stucco and brick tombs. Yet 1945 heralded a long (and ongoing) boom of new, strong, and user-friendly materials that would widely be seen in New Orleans cemeteries. This technological and cultural boom contrasted with some of the oldest cemeteries in the city, which were seen as outdated and, at worst, nuisances. Such was the case for Girod Street Cemetery. The Protestant cemetery, founded in 1822, had long been considered an eyesore. As early as the 1880s, the state government of Louisiana considered closing the low-lying cemetery altogether. By the 1940s, its condition was such that cemetery authorities took action. In 1945, officials at Christ Church Cathedral conducted a survey of Girod Street – “the first Protestant burial ground in the Lower Mississippi Valley" – and concluded that “some 1000 of the old vaults and tombs in which many of the city’s prominent and wealthy families were buried are a menace to public health.[4]” Each of these vaults and tombs was marked on All Saints’ Day 1945, and posted with a notice to families that the tombs must be repaired within 60 days. If no action was taken, said the city public health department, the tombs must be demolished. Reports from the sexton of Girod Street Cemetery suggested that as many as forty families did respond to the notices. However, it was too late for Girod Street Cemetery. The burial ground was deconsecrated in 1957 and demolished. The remains of white bodies were re-interred in Hope Mausoleum, and burials of African Americans were interred at Providence Memorial Park. [1] “Move to Return War Dead Begun,” Times-Picayune, April 5, 1945, 27.

[2] “Orleanians Plan Halloween Observance in Usual Style,” Times-Picayune, October 31, 1945, 4. [3] “Up and Down the Street,” Times-Picayune, October 11, 1945, 34. [4] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945, 12; “Girod Cemetery Inspected,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945, 5.

3 Comments

Herman

11/3/2015 04:23:47 pm

A succinct and well thought out history of the war era cemetery. I was especially moved by the last paragraph.Thank you.

Reply

11/3/2015 07:37:20 pm

Herman, thanks so much for the kind words.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly