|

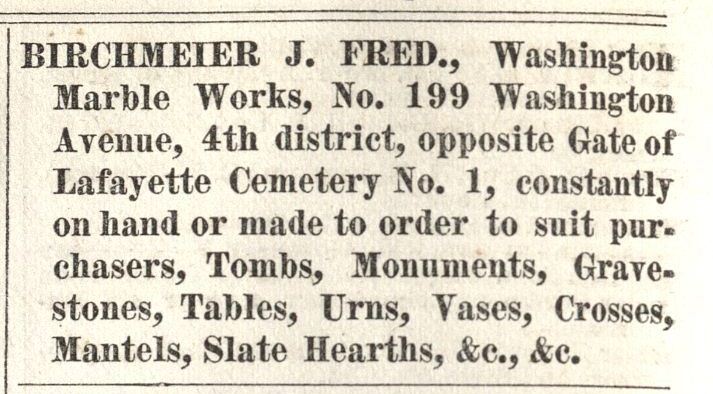

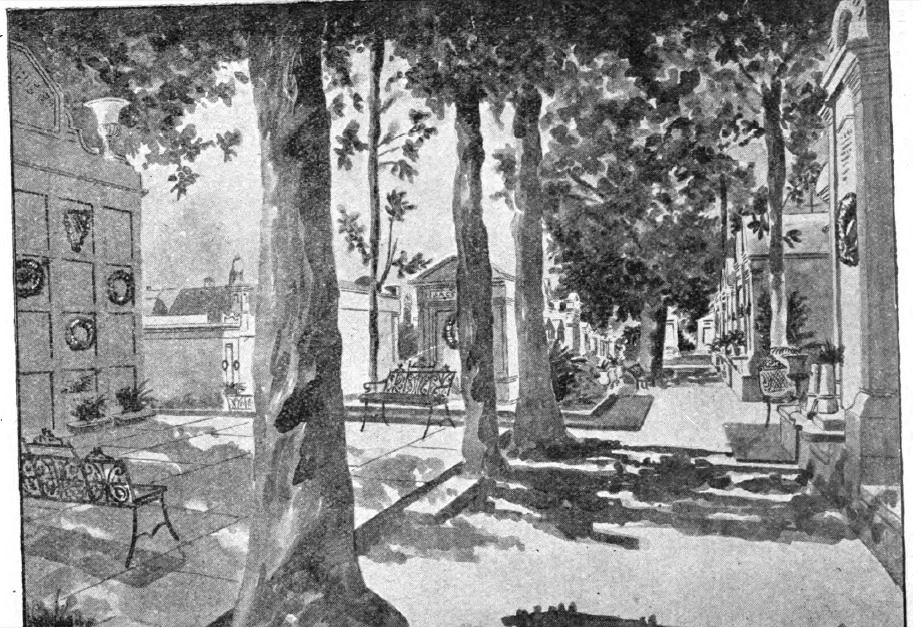

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. Full text here: http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/ The history of sextonship in New Orleans is as old as the city’s cemeteries. The origin of the cemetery sexton derived from European tradition, in which the sexton would care not only for the graveyard surrounding a church sanctuary, but also for the church itself. In New Orleans, the first sextons likely were part of a lay ministry, employed by the Catholic Church to care for St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and, later Saint Louis No. 2. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, however, was not administered by the Church or any other religious group. Instead, it was established in 1833 by the municipality of Lafayette, a suburb of New Orleans. Translating from the ecclesiastical to the secular sphere, the City of Lafayette employed a sexton to care for the cemetery at Washington Avenue and Prytania Street. From the cemetery’s founding into the 1950s, at least twenty-two individuals served as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Many were stonecutters and tomb builders, some were additionally undertakers, politicians, and masons. They cared for the cemetery in times of epidemic, vandalism, and population shifts. Through their stewardship, the landscape of the cemetery was formed. Phil Harty and the First Sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Up to and after the City of Lafayette was incorporated into the City of New Orleans in 1852, the role of the sexton was to perform and record interments, submit interment records to the city council, and maintain the cemetery grounds. It was also his responsibility to enforce the ordinances of the city and state regarding interments and sanitary conditions.[1] These laws included the collection of a certificate of burial (presented by a physician or coroner to the deceased’s family), ensuring the deceased was properly placed in a coffin, and construction regulations regarding tombs. Failure to perform these duties resulted in punishment from City Council.[2] Sextons were additionally paid a fee for each interment based on the deceased’s status as colored or white, child or adult, and whether the interment was to be an act of charity. In the nineteenth century, these fees varied from 50 cents to $1.50, with a $3.00 charge for the opening and closing of tombs and vaults, to be paid by the owner.[3] The first sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was most likely B.S. Quinman, who served from 1832 to 1844.[4] After Quinman, H.G. Hicks served briefly in the position. While many sextons constructed tombs in Lafayette No. 1, no structure or tablet in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 bears either man’s signature. Their successor, however, seems to have made more of an impact on the cemetery. Philip Harty, mostly referred to in documentation as Phil Harty, served as Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 sexton from 1855 to 1861. [5] Only one of his signed works survive amidst the rows and aisles of tombs: the tomb of A. Thomas, located near the rear gate.[6] He lived at 197 Washington Street, across from the main gate of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. This address was utilized by numerous sextons and stonecutters throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Today, the lot is listed as 1427 Washington Avenue. The building is currently utilized as the administrative offices for Commander’s Palace restaurant. Phil Harty died August 14, 1861. His obituary, describing his death as “sudden,” states that Harty was well-known as a sexton and a “hearty, merry fellow up to the very hour of his death. Thousands he has introduced to the narrow house, and now he has gone himself, with scarcely a moment’s warning.”[7] D.F. Simpson, a local stonecutter, followed Harty as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1863 to 1868. He was also a stonecutter and tomb builder – his office was located on Race Street.[8] Examples of his work remain in the cemetery today, including the Stearns tomb and at least three constructed while Simpson was in business with later sexton J. Frederick Birchmeier. Following D.F. Simpson were James Hagan (1830-1908, sexton 1865-1867), and Joseph F. Callico (sexton 1867-1875).[9] James Hagan served as state senator representing Orleans Parish from 1880 to 1884. Based on remaining signed tombs and closure tablets, J.F. Callico was one of the most prolific stonecutters among the sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1: today, nearly thirty tablets in the cemetery bear his signature. 1865 – 1900: A Thriving Craft Community The late 1870s were unusual for the stewards of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in that no one individual served for more than a few years. As had occurred in previous years, especially 1853, yellow fever epidemics were particularly difficult times for sextons. It is possible, then, that the 1878 epidemic, the marks of which are still very visible on the tombs and tablets of Lafayette No. 1, caused an upset in the administration of the cemetery. In quick succession, Dennis Irvin, Cornelius Donovan, John Barret and Patrick Gallagher served as sextons from 1876 to 1880. Patrick Gallagher likely left his office due to accusations against him that he attempted blackmail on an unnamed person.[10] After these men, J. Frederick Birchmeier, a stonecutter who had been active in Lafayette No. 1 for decades, became sexton.[11]

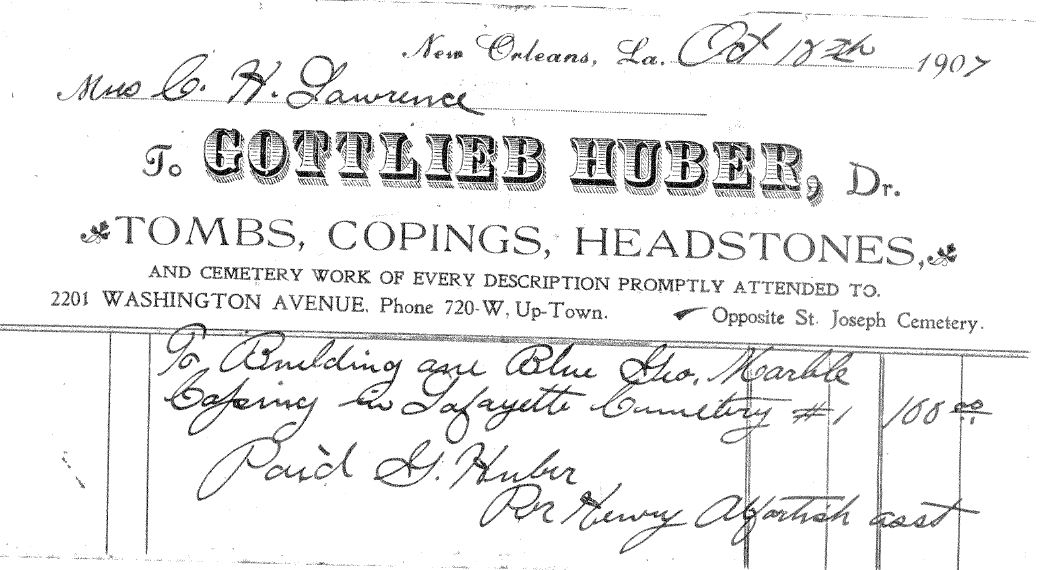

The turn of the twentieth century brought to Lafayette No. 1 a close-knit community of stonecutters and tomb builders, many of whom served as sextons. After J. Frederick Birchmeier retired, his colleague Hugh J. McDonald (1853-1895, sexton 1886-1895) took over stewardship of the cemetery. After McDonald’s death, stonecutter Charles Badger succeeded him. Badger was also the husband of Birchmeier’s daughter, Margaret.[14] Both Badger and McDonald were close colleagues of Gottlieb Huber, who was sexton from 1902 to 1915. The legacy of this community would continue for the next thirty years through another young protégée of these men. 1900 – 1945: The Alfortishes In 1911, Henry Alfortish became assistant to Gottlieb Huber at Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Alfortish also worked with Huber privately, and would absorb Huber’s business after his death in 1926.[15] The influence of Alfortish and, later, his son Edward, would greatly change the cemetery. In the 1920s, Alfortish declared numerous lots abandoned and “open for sale.” He sold these lots and tombs to new clients and, additionally, provided replacement deeds for families who had lost their tomb ownership documents. It was also under the sextonship of Henry Alfortish that the wall vaults once located along Sixth Street were cleared and demolished. Numerous coping tombs located along this wall today bear Alfortish’s signature.[16] Edward Alfortish assumed sextonship of Lafayette No. 1 in 1942. However, the role of sexton was no longer seen as relevant in the city-owned cemetery. Few burials were made compared to the heyday of Lafayette No. 1, and many of the responsibilities of sexton could be carried out by other city officials. By around 1950, no individual would serve as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 again. The caretakers of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1833 to 1950, built the cemetery as it is seen today. They designed and constructed its tombs, removed and replaced landscape features, fostered its dead and their families, and protected the cemetery from harm. Their names are placed alongside the names of Lafayette No. 1’s most famous residents, in the form of carved signatures at the bases of closure tablets and headstones. The story of this National Historic Landmark cemetery is very much their story. [1] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4; State of Louisiana, The Revised Statutes of Louisiana (J. Claiborne, 1853), 386.

[2] “City Intelligence: Board of Health,” Daily Picayune, August 4, 1853, 1. [3] Ibid.; Currency evaluation oriented around historic standards of living, these costs equate to approximately $20-$40 per interment and $81 (2011 dollars) for the opening/closing of a tomb or vault. (www.measuringworth.com) [4] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84 (Baton Rouge: Leon Jastremski, 1884), 40. [5] Daily Picayune, February 15, 1855, 6; Mygatt & Co.’s Directory for New Orleans, 1857, W.H. Rainey Compiler. L. Pessou & B. Simon Lithographers, 23 Royal Street, New Orleans, 1857, 49; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for the Year 1859 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1858), 377; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1860 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1859), xvi. [6] Based on a 2012 survey of all signed craftwork in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. The Isaac Bogart tomb, located in Quadrant Three of Lafayette No. 1, is documented in the 1981 Save Our Cemeteries/Historic New Orleans Collection Survey of Historic Cemeteries as having a tablet signed by Phil Harty. The tablet has since been lost. [7] “Sudden Death,” Daily True Delta, August 15, 1861, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 18, 1866, 3. [9] Based on directories and municipal documents. [10] “An Official Suspended,” Daily Picayune, October 9, 1878, page 2. [11] Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1880 (New Orleans: L. Soard’s Publishing Co., 1880), 456; Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1882 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1882), 142; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1883 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1883), 452. [12] “A Singular Case,” Daily Picayune, June 14, 1868. [13] Receipt from J. Frederick Birchmeier to the widow of John Paul, Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 365. [14] Daily Picayune, February 8, 1891, 1. [15] Times-Picayune, January 20, 1926, 2. [16] Receipts for lots Quadrant Three, Lots 16 and 17, Quadrant 1, Lots 270-275, the Moulin, Gonea, Legien, and Bittenbring tombs. Sexton’s book, page 127. Historic New Orleans Collection, Leonard Victor Huber Collection, MSS 365.

3 Comments

5/8/2016 07:19:58 pm

Of course I like it! I'll recommend it to Gray

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly