|

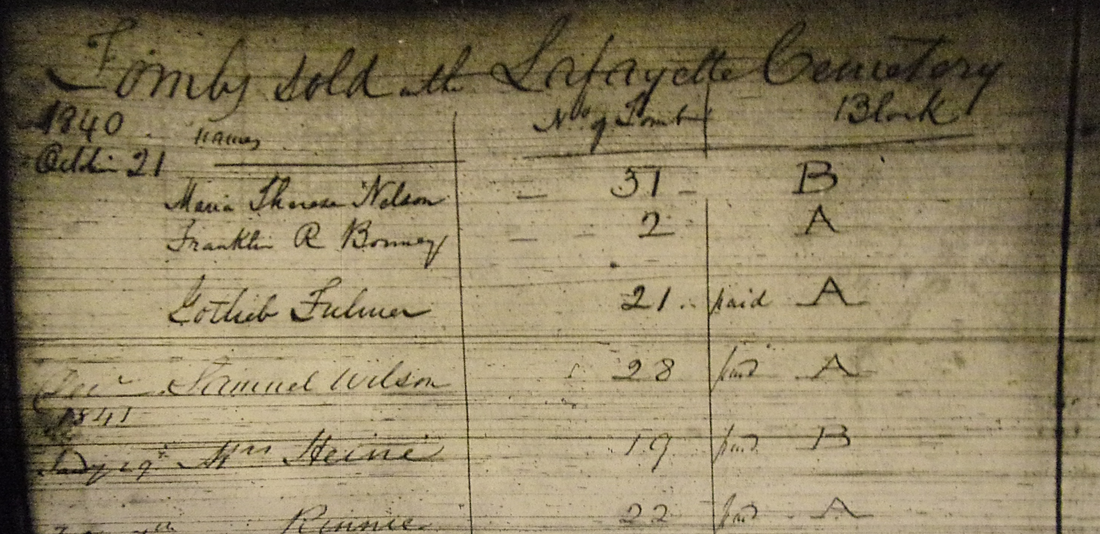

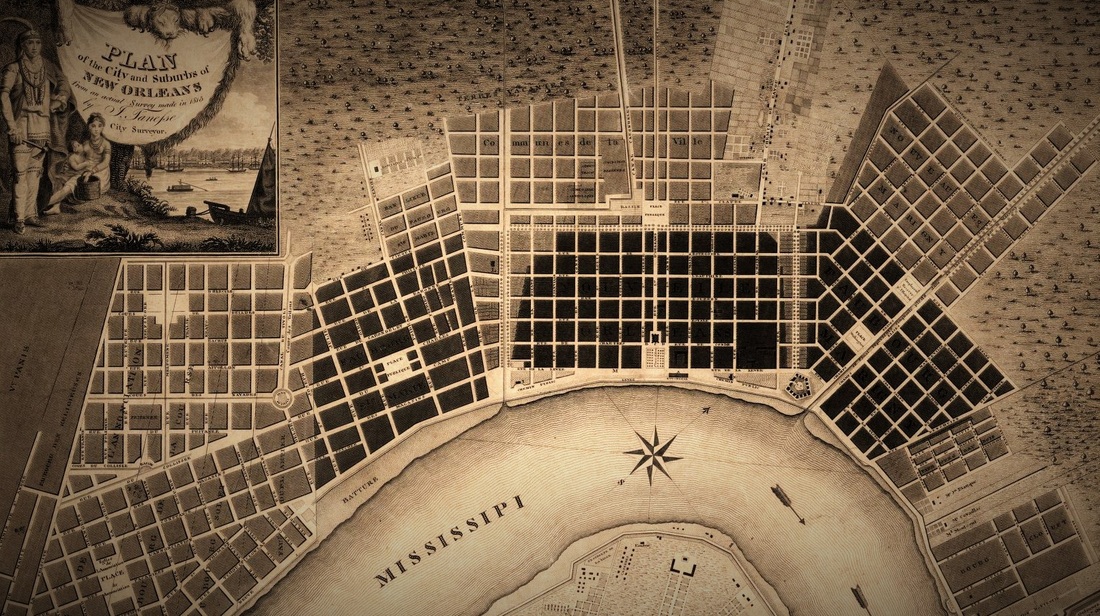

Find your tomb, Research your tomb, Restore your tomb The text below is excerpted from a recent presentation to the 2016 Annual Conference of the Louisiana Historical Association, presented by Emily Ford, MSHP, of Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LL New Orleans cemeteries are so unique that the simple mention of them creates a picture in one’s mind. That picture is likely one of intricate aisles populated by stately, yet crumbling, above-ground tombs; long abandoned, anachronistic cities of the dead which offer up stories through their carved tablets. Traditional histories of New Orleans cemeteries have been static, and ever tied to their place in popular culture. For example, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as part of what is now the Garden District. Over the next century, families built above-ground tombs ranging in style from simple masonry structures to grand Classical revival masterpieces. From this foundation, the interpretation of the cemetery usually branches into famous people buried therein, or a focus on specific architectural gems. These interpretations usually rely on a few primary sources. Some cemetery records, selected newspaper articles, and general contemporary observations of the cemetery as it exists in the moment tend to dominate the narrative. What few critical analyses of cemetery architecture exist tend to be repeated through numerous secondary sources. This tends to amplify their subjects as singularly important. For example, the excellent research of Patricia Brady on the stonecutter Florville Foy published in 1993 has been so revisited that the place of Foy among hundreds of other nineteenth century stonecutters appears paramount, as opposed to part of a larger craft community.[1] Beyond the few comprehensive histories relevant to New Orleans cemeteries lie the bulk of what is currently available – histories that focus on cemetery “residents” (for example, Marie Laveau or Colonel Harry T. Hays), high architecture, or the occult. These histories rely on the basic historiographies previously mentioned and typically add curious second-hand stories or rehashed false reports. For example, the translation of the tablet of André Valsin Labarre in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 has been repeated incorrectly for more than a century, but never once has it been noticed that it is located in the wrong lot.[2] Conversely, more dynamic and critical approaches to writing cemetery history will inevitably stumble upon landscapes which dramatically changed as their stakeholders did. For example, the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was not always one of above-ground tombs. The first stakeholders in this cemetery, predominately German and Irish immigrants, found above-ground burial to be perverse, and instead buried below ground. It was not until the 1850s, when their assimilated children gained control of the family lot, that tombs were constructed to emulate the New Orleans ideal.[3] Facts like this not only present a more accurate history of each cemetery, but also accentuate the changing uses each lot would see over time. Sale of lots, demolition of tombs, changes in materials, adaptive reuse, abandonment, and changes in technology are a constant presence in the history of any New Orleans cemetery. Consideration of these details empowers preservationists, stakeholders, and cemetery authorities to more appropriately care for these resources. By shifting the view of cemeteries from that of static landscapes (“outdoor museums”) to one of functional cultural resources, their history and their preservation are dually served. A critical approach to cemetery history combines a multifaceted catalog of primary resources. Original records vary in their condition and availability. With regard to tomb construction, cultures of craft typically focused on the final product and not on drawings, plans, or specifications. In order to piece together the history of a New Orleans cemetery, some creative and rigorous searching is in order. By pairing what primary resources are available with thorough and educated examination of the landscape itself, it is possible to determine the life story of any city of the dead. Original Cemetery Records There are between 32 and 46 historic cemeteries in New Orleans, depending on the criteria employed. Each one is unique in age, architecture, and culture. They also vary in terms of ownership and, thus, quality and location of records. In general, there are four types of cemetery ownership –

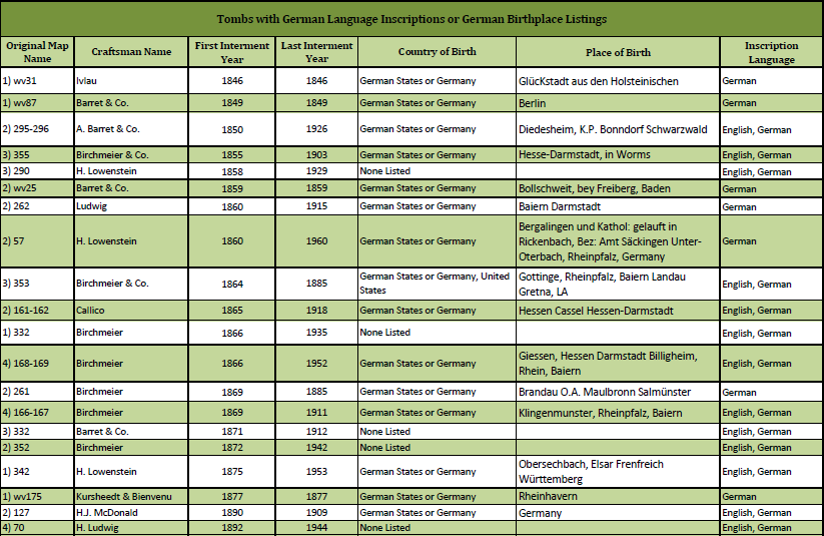

Records of cemetery burials, constructions, demolitions, or demographics were kept by the owning body of each cemetery. Owning bodies vary in their methods of access, preservation, and retention of records. Historic Images What cemetery records cannot contribute to the preservation and documentation of cemeteries is often accessible in a variety of traditional and non-traditional photographic resources. The use of historic photographs in the identification of property and the preservation of individual tombs has not been frequently visited. Furthermore, many photographs which can prove crucial to preservation efforts are difficult to find. When located, however, these photographs can tell the story of an entire cemetery, save a tomb from demolition, or re-unite a family with their property. The photographs of Clarence John Laughlin are an excellent example. Recently digitized by the Historic New Orleans Collection, the photographs date from the 1930s through the 1970s. Laughlin’s prolific hauntings through New Orleans cemeteries prove to be time capsules without compare. Identification of precise location of photographs yields not only histories of specific structures but also entire landscapes. For example, a 1920s postcard showing St. Roch Cemetery and a 1907 photograph of Holt Cemetery show an overwhelming prevalence of wooden markers. Comparison with present-day landscapes indicates enormous changes in the use of cemeteries over time – notably, the industrialization of the monument industry by mid-twentieth century. This shift overwhelmingly transformed cemeteries from highly individualized properties maintained by families to largely mono-stylistic landscapes maintained by cemetery staff – or not maintained at all. As we move into the twenty-first century, the presence of Hollywood in New Orleans cemeteries has created a new type of historiography. Productions like Easy Rider, Love Song for Bobby Long, NCIS, and dozens of others with scenes taking place in New Orleans cemeteries inadvertently document them. Easy Rider is a significant example. Fortunately for historians and preservationists, Peter Fonda’s place in the arms of the statue of “Italia” provides an image taken only years before a heavy-handed “restoration” permanently damaged it. Ephemera and Oral Histories Numerous resources exist beyond photographs and scant cemetery records. These require some amount of supporting evidence, and are best paired with observations of the built environment itself. Some ephemeral records were produced by the purchasers of the tombs themselves. Tomb deeds, once a common part of family papers, are rare, but those that do exist show that many tombs have a chain of title. Such evidence is also present in the notarial archives of tomb builders like Hugh McDonald, Paul Monsseaux, and James Hagan. The full potential of all of these resources is reached when paired with on-site examination of the landscape. This is achieved through painstakingly inspection of tombs for alterations, materials, and inscriptions. Larger-scale data collecting also proves fruitful. For example, while primary resources suggest stonecutter Anthony Barret predominately served a German-speaking market, database compilations of his signed work in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm the breadth of his presence in the German community. These conclusions are additionally supported by oral histories and interviews with the ever-dwindling community of cemetery craftsmen and caretakers, whose potential has rarely been formally tapped. In conclusion, the hidden historical record of New Orleans cemeteries reveals dynamic landscapes that were specific to their community, and constantly shaped by that community. By resurrecting these histories, which highlight stewardship, family involvement, and participation with cemetery authorities, these values can be preserved. Through these means, we can more accurately represent New Orleans heritage and community agency for those who take interest in it and are inheritors of it. Have questions about cemetery interment research or architectural histories of cemetery properties? Contact Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. [1] Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.: Master Marble Cutter and Tomb Builder.” Southern Quarterly 32, no. 2 (Winter 1993): 9-20.

[2] Emily Ford, “André Valsin Labarre: Victime de Son Imprudence,” http://www.oakandlaurel.com/blog/andre-valcin-labarre-victime-de-son-imprudence (January 9, 2016). Based on in situ investigation, Archdiocese records, and 1930s WPA Index (housed at NOPL), this well-known tablet has travelled from Labarre’s actual resting place. [3] “History and Incidents of the Plague in New Orleans,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7 (June-Nov. 1853), 798; Bennet Dowler, Researches upon the necropolis of New Orleans, 22; George Edwin Waring and George Washington Cable, History and Present Condition of New Orleans, Louisiana, and Report on the City of Austin, Texas (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1881), 58; John Frederick Nau, The German People of New Orleans, 1850-1900, 15. Architectural histories within the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm this progression from below-ground burials to above-ground tombs and (eventually) copings.

4 Comments

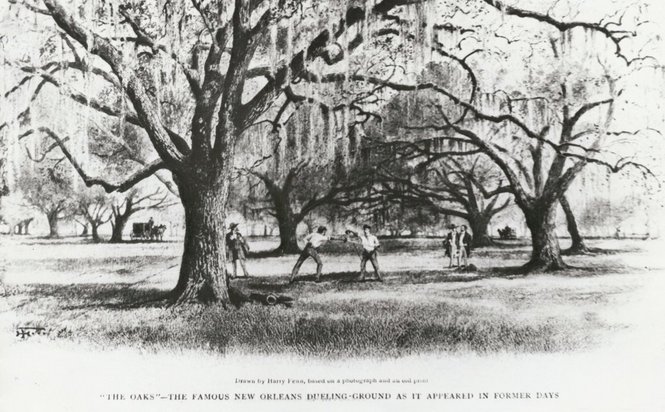

On March 6, 1888, Don José “Pepe” Llulla died in what is now the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans. At the age of 73, Llulla had made himself famous for two things: he was a renowned duelist, and he also owned St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery. Llulla’s life was the kind from which New Orleans legend are spun. He was a valiant Spanish swordsman who frequently took up the mantles of honor and integrity on the field of one-on-one battle. Upon being knighted by the King of Spain, he was gifted a wreath of victory spun from the shining tresses of Spanish women’s hair. He once pulled a machete on a Cuban revolutionary. His legacy, then, is double-edged: Llulla’s contribution to the landscape of New Orleans cemeteries is second only to his impact on the city’s romantic imagination.[1]

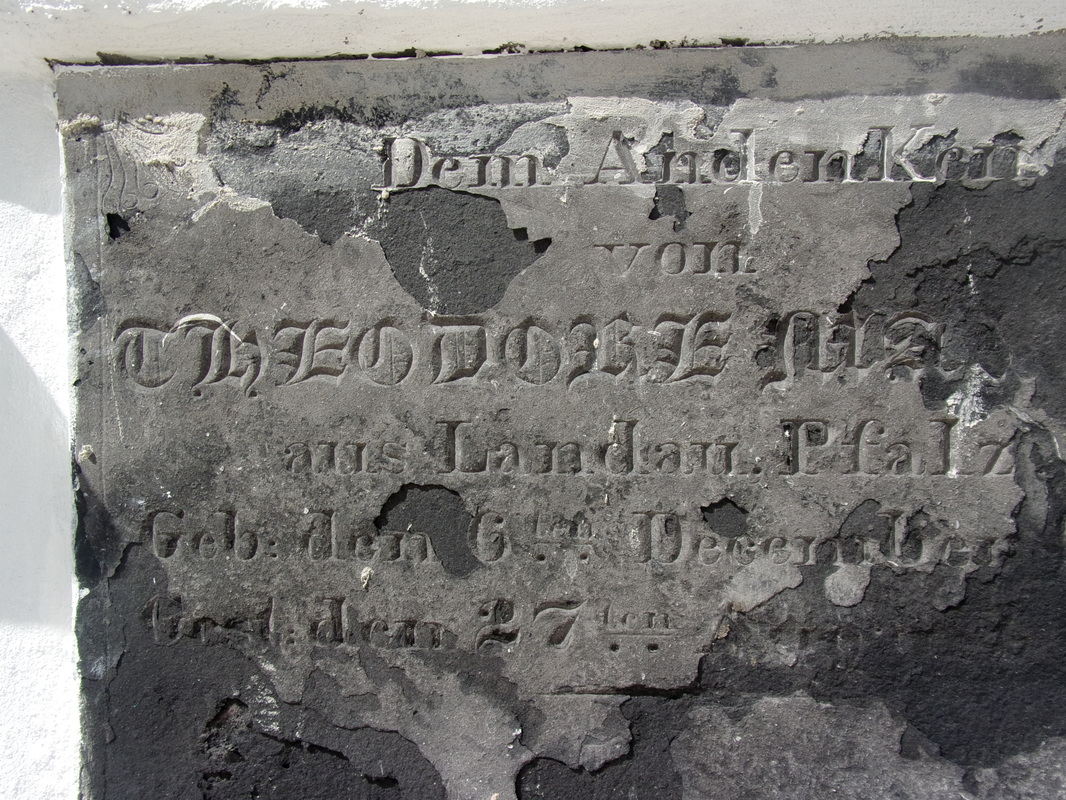

The nature of his work in New Orleans caused Llulla to gravitate toward the art of fencing, which was practiced not only in combat but in private salons. Llulla studied under a local duelist from Alsace named L’Alouiette, whose salon he later took over and became teacher himself. From here, Llulla’s reputation as a witty, cunning, and skilled fencer and duelist only grew. Although additionally skilled with firearms, his weapons of choice were more often swords, foils, and (to a lesser extent) knives. Accounts differ as to how many duels Pepe Llulla actually engaged in (and won), but they generally agree between twenty and thirty matches. Hearn notes that many of these ended not in bloodshed but with the retreat of his opponent. In fact, he suggests that Llulla only actually killed two men. The only match which Pepe had declined was reportedly one in which the opponent chose “poisoned pills” as his weapon of choice – a type of Russian roulette with cyanide – and this only after objection from the duel’s referees. While Llulla’s opponents on the field of honor were of many backgrounds – New Orleans Creoles, Alsatians, Germans, and others – he made special efforts to combat Cubans. The man with the poisoned pills was from Havana. In another instance, a Cuban opponent chose machetes as the weapon of choice, as he believed that such weapons were not available in New Orleans. From the account, it appears as if Llulla instantly produced two matchetes, at which point the Cuban disappeared. Beginning in the 1860s and finally culminating decades after Llulla’s death, the cause of Cuban independence from Spain had a theater in New Orleans. Cuban revolutionaries frequented the Louisiana port and sought support among the Spanish-speaking citizens of the city. Llulla’s passionate Spanish patriotism flared especially against these men, whom he saw as traitors. Reportedly, he posted flyers all over New Orleans in French, English, and Spanish languages, challenging any Cuban revolutionary to duel him personally. Llulla’s reputation and bravado prevented any takers to this challenge, although it did lead to a number of assassination attempts, one of which reportedly occurred in Llulla’s own cemetery, although he escaped unharmed. For his bravery and loyalty, Llulla was formally knighted by Kings Charles III of Spain, who awarded him “a wreath and likeness of himself made from the silken tresses of Spanish ladies’ hair.”[4] Through his lifetime, Pepe Llulla dabbled in many different business ventures. He purchased real estate and ran a logging company. For some time, he staged bull fights in Algiers. Yet he is best remembered as the proprietor of the “Louisa Street cemeteries,” which he likely purchased in the 1840s – although one source states date of purchase as 1857. “One of Our Finest and Best-Managed Burial Grounds” St. Vincent de Paul Cemeteries No. 1 and 2 are located on Louisa Street, near Robertson in the St. Claude neighborhood of New Orleans. Often confused with another set of cemeteries with the same name located Uptown, these cemeteries were likely the parish cemeteries for the Catholic church of St. Vincent de Paul, located on Dauphine Street in the Bywater neighborhood. The exact founding date of this cemetery is quite unclear. Some sources have presumed the property came into use as a burying ground in the 1830s, but an exact citation or primary source is not provided. In fact, the exact year in which Llulla purchased the cemetery remains unclear. On the far periphery of twentieth century studies of New Orleans cemeteries, St. Vincent de Paul experiences the twin historical blows of scant documentation and academic apathy.[5] Despite its present-day low profile, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery flourished under the management of Pepe Llulla. Wall vaults in the cemetery’s oldest sections are galleries for some of the most talented stonecarving of the 1840s and 1850s – the delicate hand-tooled flowers of Florville Foy, ornate German Fraktur by Anthony Barret, inverted torches and wreaths carved by Americo Marozzi and Audré Samonzet are all present. The integrity of these stones surpasses that of even the older, better-known St. Louis Cemeteries, which have been frequently altered over time. Most of these tablets are framed with railings of cast- and wrought-iron, accented with zinc finials. The aisles of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery No. 1 retain the marks of large-scale tomb development. Rows of identically-built structures line the brick-paved walkways, each bearing the alterations and changes in material that would develop over time and use. The society tombs of the United Brethren and Sons of Louisiana (signed by “Joseph Llulla, 1873”) while today faded from their Classical-revival glory, bely the historic grandeur of the landscape. In the 1870s, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery was described as “one of our finest and best-managed burial grounds” by the New Orleans Democrat. By this time, the cemetery had developed into a verdant landscape with reportedly excellent drainage – a constant problem in New Orleans cemeteries. Juniper and cedar trees shaded the aisles, roses and other fragrant flowers grew in the garden lot of the Hermann Lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (no longer present today). Newspapers even took note that families in Uptown New Orleans had begun to purchase lots in St. Vincent de Paul, preferring it to the Lafayette Cemeteries of their home district.[6] Above Left: 1845 tablet in French carved by German carver Vlau. Above Right: 1853 tablet for Cuban native, carved by French carver Florville Foy. Bottom Left: 1862 tablet in German carved by Italian carver Azereto. Bottom Right: 1852 tablet in French carved by Italian carver Parelli. (Photos by Emily Ford) The cultural associations of those who buried loved ones in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery No. 1 and 2 are strikingly diverse. While in other cemeteries it is clear that those with linguistic or national similarities typically utilized the same burying grounds – for example, French-speakers in St. Louis No. 2, Americans in Lafayette No. 1, Italians in St. Roch No. 2 – St. Vincent de Paul represents all walks of life and nations of origin. Tablets in French, English, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and even Chinese line its wall vaults. In addition to the tombs of the French Sons of Louisiana and the Societe Francaise, St. Vincent de Paul was also once home to tombs dedicated to the members of the German Louisiana Wolthatickeits Verein and Italian Tiro al Bersaglio, although both tombs have since disappeared. Pepe Lulla never married, but did have at least three children - Joseph, Jr., Isabella, and Louisa. His two daughters married two brothers - Manuel and Vincente Suarez. Joseph Jr. and Isabella passed away before their father's death in 1888, and he left his estate and cemetery to his daughter Louisa. For the next two decades, the cemetery was under her care and that of her husband Manuel. [8] The landscape of the cemetery shows slowed development and little new tomb construction with the exception of some large, 1920s-style tombs near the Villere Street wall vaults. St. Vincent de Paul No. 2, which sits between Desire and Piety Streets, shows an explosion of coping construction, likely between 1910 and 1930. It was during this period that two of St. Vincent de Paul’s more famous “residents” were buried, the African American spiritualist leader Mother Catherine Seal and the Romany “queen” Marie Boscho.[7] In 1910, ownership of the St. Vincent de Paul Cemeteries transferred to the Stewart family. Stewart Enterprises later became the second-largest funerary corporation in the world, which also owned Metairie-Lakelawn Cemetery and Mount Olivet Cemetery in Gentilly. During this time, St. Vincent de Paul No. 3 was heavily developed, including a large community mausoleum on Villere Street. In 2005, a service building and other property belonging to St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street was damaged in Hurricane Katrina and was demolished. In 2013, Stewart Enterprises was purchased by first-largest funerary corporation Service Corporation International (SCI), who now owns St. Vincent de Paul Nos. 1, 2, and 3. A Threatened Legacy In 2015, SCI announced that it would spend $7.2 million in “improvements” to its recently-acquired cemeteries in New Orleans, including St. Vincent de Paul. Unfortunately, these improvements have dangerously ignored preservation ethics and best practices. For St. Vincent de Paul No. 1, this has meant encasing the Louisa, Urquhart, and Piety-street wall vaults in heavy, inappropriate Portland cement-based stucco, as well as treating its 140 year-old tablets with harsh bleach and pressure washing. Perhaps most troubling, the delicate ironwork rails that once framed each wall vault have been torn out and lay entangled in the cemetery’s aisles. The extent of the damage to these vaults will only be truly visible in decades to come, when material constrictions, lack of ventilation, and material weight will destroy the historic fabric underneath. The legacy of Pepe Llulla is one of romance and anachronistic bravado, of sword fights and burning candles on marble tombs through the night of All Saints’ Day. The place of the cemetery he built in New Orleans’ larger funerary landscape is much more important than it has been given credit for. If this fact is not soon realized, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery will be lost before it is ever truly understood. [1] The vast majority of knowledge regarding Don Pepe Llulla comes from the observations of Lafcadio Hearn, whose documentation of Llulla appears to have influenced all later writing on the man.

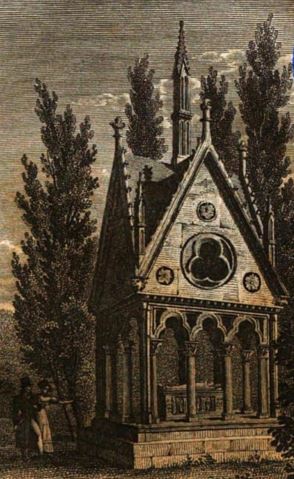

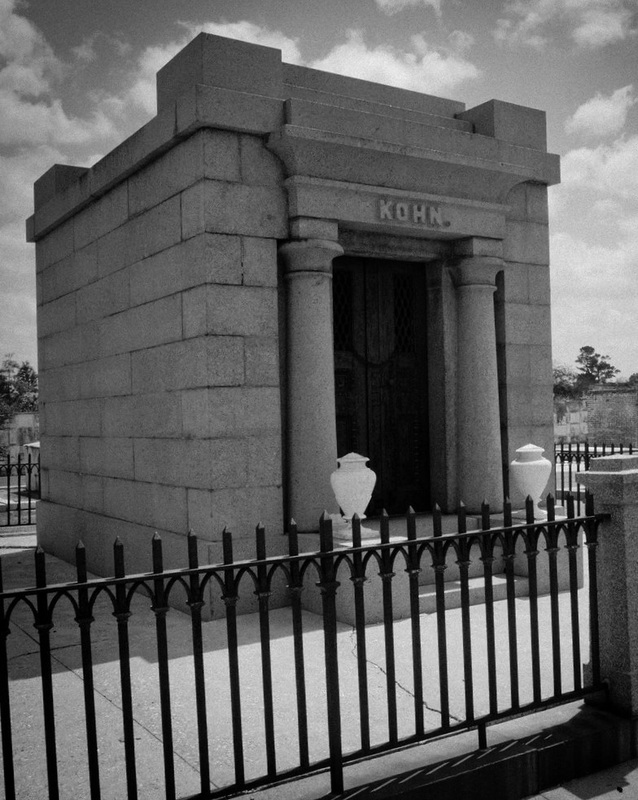

Lafcadio Hearn, and S. Frederick Starr, ed., Inventing New Orleans: The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 49-60. [2] Ciaran Conliffe, “Jose ‘Pepe’ Llulla: The Gravedigging Duelist,” http://www.headstuff.org/2015/03/jose-pepe-llulla-the-gravedigging-duellist/ [3] Hearn, 52. [4] “Death of Senor Don Jose Llulla,” States Item, March 7, 1888, p. 4. [5] Christovich, Huber, et. al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1974), 32. [6] “A Mournful Holiday. How All Saints’ Day Was Celebrated in Our Cemeteries,” New Orleans Democrat, November 2, 1878, p. 8; “All Saints’ Day. An Outpouring of All Our Population to Decorate the Graves,” New Orleans Democrat, Nov. 2, 1878, p. 1. [7] Author Zora Neale Hurston wrote an excellent piece on Mother Catherine, which can be read here: http://www.fiftytwostories.com/?p=1068. [8] Thank you to descendants of Pepe Llulla - Nancy Suarez Gustitus, Linda Suarez Lee - and Marga Llull for correcting and clarifying the succession of Pepe Llulla, Louisa Llulla, and the Suarez brothers. As any narrative on de Pouilly does, this article relies on the groundbreaking research and thesis of Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University thesis, 1992. Which exquisitely analyzed de Pouilly’s work in New Orleans cemeteries. One hundred and forty years ago, on February 21, 1875, Jacques Nicholas Bussiere de Pouilly died in his home on St. Ann Street. In his seventy years of life, de Pouilly had been the harbinger of European neoclassical and revival architecture in New Orleans. We see his touch on our city streets – in St. Augustine Catholic Church, and most notably St. Louis Cathedral. But his influence was arguably greatest in the city’s cemeteries. De Pouilly’s work is present in nearly every viewpoint of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, and much of Cypress Grove Cemetery. The breadth and innovation of his tomb architecture generated uncountable replications and inspirations, the products of which have shaped our burial grounds. J.N.B. de Pouilly was born in July 1804 in Châtel-Censoir, France, southeast of Paris. While much of his early life is unclear, it is assumed that in his architectural training he was influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, if not a student of the school himself.[1] He arrived in New Orleans in 1833, a time in which the French-speaking population of the city hungered for reconnection with Continental styles. He quickly became the architect of note for the city’s First District, designing the St. Louis Exchange Hotel, among many other residential, commercial, and religious projects.

While Père Lachaise and Creole cemeteries like St. Louis may appear stylistically similar, de Pouilly had the significant task of fundamentally shifting the function of his New Orleans tombs from their Parisian prototype. Although the monuments of Père Lachaise appear to be tombs or mausoleums, their design accommodates instead for below-ground burial. That the architect’s designs kept their Parisian aesthetic while having been fundamentally re-worked to allow for above-ground burial is among the more impressive of his professional achievements.[3]

In addition to the French St. Louis Cemeteries, de Pouilly worked also in American-dominated Cypress Grove Cemetery (est. 1840). In Cypress Grove, de Pouilly additionally contracted with granite magnate Newton Richards to build the memorial of fallen firefighter Irad Ferry (died 1837). He relied, too, on Monsseaux and Foy to construct such masterpieces as the Maunsel White tomb. De Pouilly clearly had a strong grasp on the value of trade and materials, based on his choice of craftsmen and his apparent innovations in the world of cast stone. De Pouilly’s career was marred by two construction disasters in the 1850s – first, the collapse of the central tower of St. Louis Cathedral while de Poilly was head architect, and second the collapse of a balcony at the Orleans Theatre. From this point onward, his rising star waned, but it appears never to have faded in New Orleans cemeteries. In 1874, de Pouilly composed the final drawing in his only surviving sketchbook – a tomb he designed for himself and his family. This tomb, like many depicted in his prolific sketches, would never be constructed. Instead, de Pouilly was interred in a family wall vault in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Although the location was surely not intentional, the wall provides a lovely view of a number of de Pouilly-designed tombs. In a nearly-illegible detail to his memorial tablet, the signature of Florville Foy can be detected as the carving hand of de Pouilly's final tablet. De Pouilly’s obituary on February 22nd spoke grandly of a man who lived honestly and in service of his profession:

St. Peter’s lofty dome cenotaphs the name of Michael Angelo [sic]: Sir Christopher Wren’s greatness is sepulchred in the mightiness of St. Paul’s. Mr. De Pouilly fashioned no wonders such as these, but yet a greater, the enduring fabric of an honest life, and will be entombed in the constant remembrance of devoted friends. After a painful and lingering illness, Mr. De Pouilly, hoary with the winters of seventy years, and surrounded by children and other relatives, bade farewell to things of earth. This sad event occurred yesterday, Sunday, 21st.[4] The Daily Picayune made no note of the many cenotaphs de Pouilly himself had helped write, in the tablets and along the aisles of our cemeteries. But if 140 years is a sufficient measure of the timelessness and impact of one’s work, his name certainly engraved upon many more memorials than just his own. Below is a gallery of only a portion of de Pouilly’s work, and a few tombs inspired by his designs. Photos by Emily Ford unless otherwise noted. [1] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” 5-7.

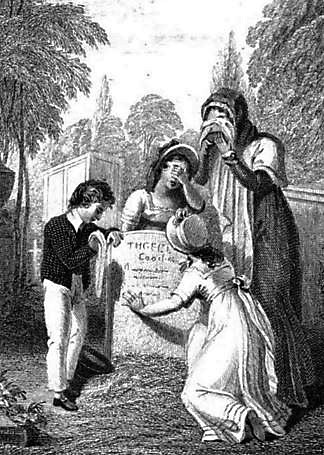

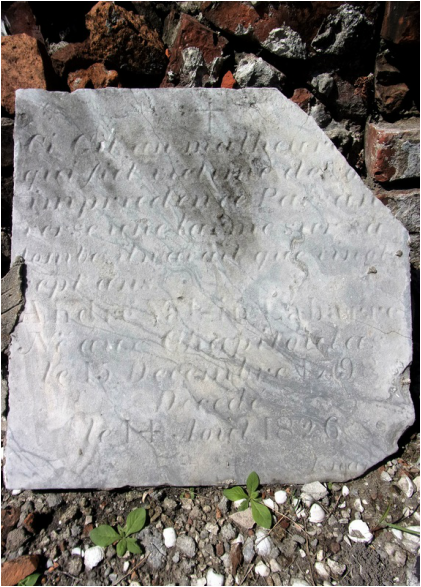

[2] Peggy McDowell and Richard E. Meyer, The Revival Styles in American Mortuary Art (Popular Press, 1994), 59. [3] Masson, 30-35. [4] “In Memoriam – J.N. de Pouilly,” Daily Picayune, February 22, 1875, 2. Special thanks to Mary Lacoste, author of Death Embraced, for drawing our attention and curiosity to Mr. Labarre. On any given day in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, hundreds of people walk down a back alley toward the “Musicians’ Tomb.” Led by tour guides, they may stop at a newly constructed-tomb or point out a newly-restored one. A few point out the tablet of André Valcin Labarre. One tour guide points to the loose-lying, grey-veined little tablet and states, “He was a bad boy,” as they walk past. The tablet is leaned up against a structure that has likely not been tended for nearly two hundred years. Half-collapsed, it is hardly a tomb any longer. Like uncountable burials in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, it is on its way to becoming completely erased. But Labarre’s tablet remains. Now broken and missing a piece, the Labarre tablet has long been referred to as among the most interesting in the cemetery. Its French inscription is difficult to read, let alone translate, but the words “victime de imprudence” remain visible. These three words have made the tablet a sensation, although nearly all accounts of its message have been incorrect. In a way, this is a story of a man who died young and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. But if this was all there was for André Valsin Labarre we wouldn’t be intrigued by him today. Instead, this is also a story of how one man’s epitaph led to a century of confused transcriptons, translations, and misunderstandings. In the nearly two centuries since his death, he continues to sow imprudence.

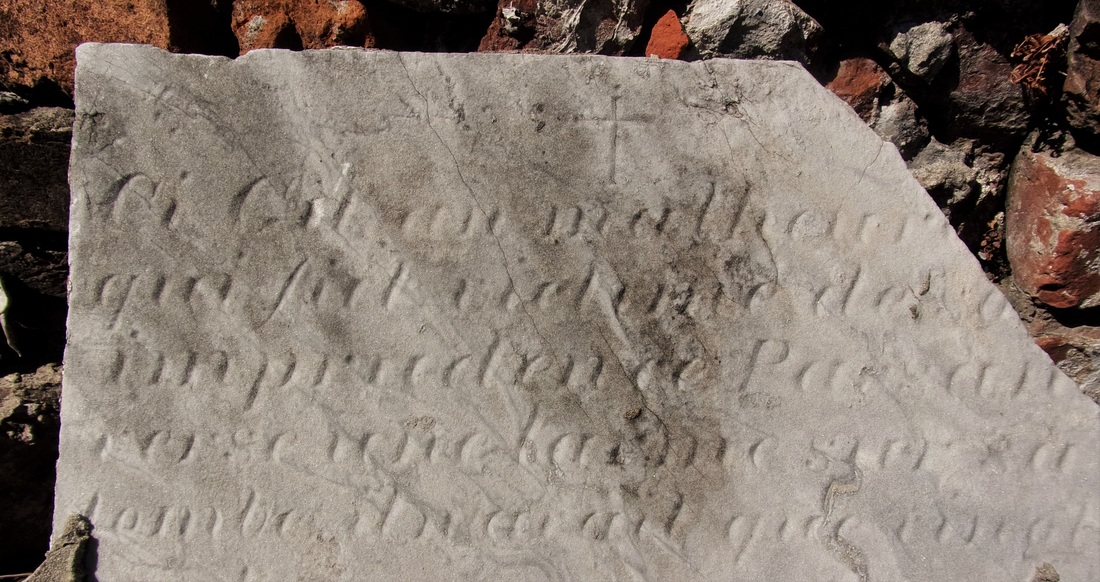

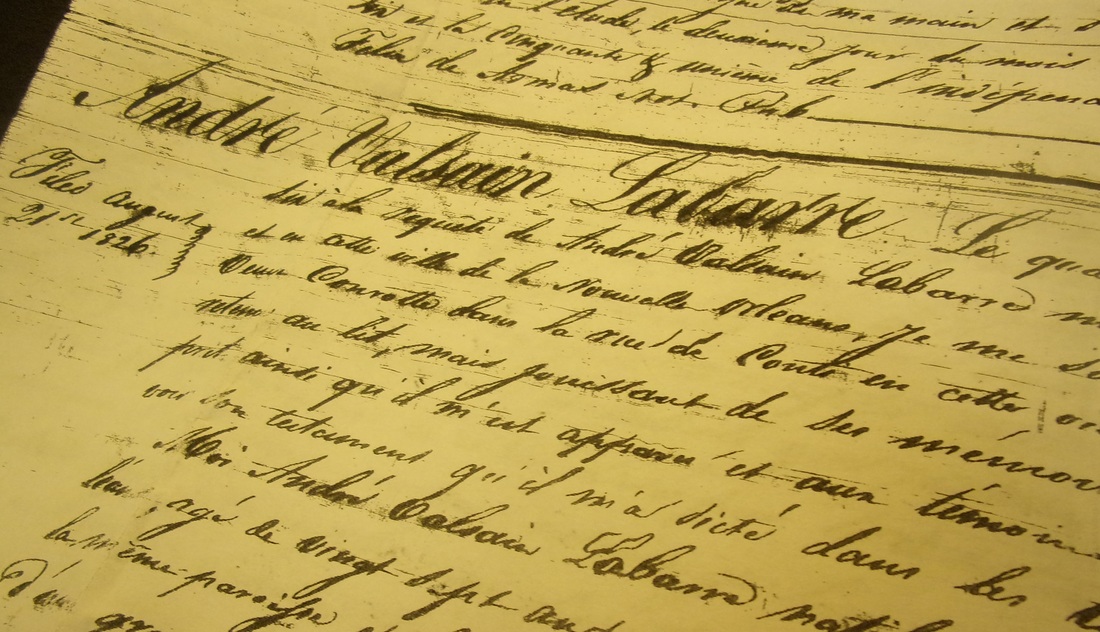

From the mid-1700s, the Labarre family owned significant holdings of land in what would become Jefferson Parish. Beginning with Francois Pascalis de Labarre Sr., who served law enforcement and municipal roles, a number of Labarre men claimed the post of sheriff in Jefferson’s early days.[2] Biographers and genealogists refer to the Labarre family as tied to their land, known as Chapitoulas Plantation or the Chapitoulas Coast.[3] The property line for this plantation is still demarked as Labarre Road in Jefferson. The family’s ancestral home, White Hall, is now home to the Magnolia School. André Valsin Labarre (usually addressed as simply Valsin) was born on December 15, 1798 at Chapitoulas Plantation. He is described as having less attachment to the plantation homestead than his parents, siblings, and cousins. According to one genealogist, Valsin was “the first of the Labarre family to move back to the city” of New Orleans since Franscois Pascalis Sr. purchased the Chapitoulas plantation in 1750.[4] Labarre lived in the Faubourg Marigny in 1822, when he married Virginie Conrotte (c. 1808-1850). The two had only one child, Samuel Placide Labarre, born December 4, 1822.[5] As for what André Valsin Labarre could have possibly done to deserve a tablet that suggests he died of his own imprudence, there is no clear answer. As we will see with later interpretations of his tablet, much is up for conjecture. His will shows a fondness for fine possessions: a “big horse of superior quality,” Spanish saddles and riding gear, a double-barreled hunting gun. He also owned five slaves: Fortune (30 years old), Thom (28), Constant (18), Maria (19), and Eliza (15). Thom and Fortune were “carters,” leading some to assume they “operated a cart and sold goods for their master.[6]” Beyond this means of income, it appears Valsin held no definite occupation, suggesting he may have been a man of leisure who enjoyed fine guns and horses.[7] On July 14, 1826, notary Carlile Pollock visited twenty seven year-old André Valsin Labarre at a home on Conti Street, likely the home of a relative.[8] Pollack was called to the house by Virginie Conrotte. Wrote Pollack: on j'ai trouvé le requerant malade retenir au lit, mais jouissant de memoire et entendement naturels, et bien d'esprit “there I found the sick man confined to his bed, but sound of memory and understanding, and in good spirits.” Pollock had been called to compose the last will and testament of André Valsin Labarre. In this will, Labarre named his oldest brother, Francois Pascalis Labarre II, executor and beneficiary of his property. He also requested that his brother care for his widow and son, Samuel Placide Labarre, and see that his son completed proper schooling.[9] No record documents exactly what had caused his illness. Valsin died on Monday, August 14, 1826, one month after writing his will. His obituary in La Courier de Louisiane only confounds the possible cause of his death, but describes him fondly: Mr. Valcin Labarre est décédé Lundi soir, à l'age de 27 ans, a la suite d'une longue et cruelle maladie. Doué d'une excellence constitution et a fleur de l'age, il semblant devoir fournir une longe carriere dans cette vies mais une entiere negligence de lui-meme a donné prise a la fatale maladie qui l'enleva a une nombreuse et respectable famille, a une interessant et jeune espouse, et un enfant en bas age. Mr. L. avait d'excellentes qualites qui le font regretter d'un nombreux cercle d'amis. “Mr. Valcin Labarre died Monday night at the age of 27, following a long and cruel illness. Endowed with an excellent constitution and in the flower of his age, it seemed he should have had a long career in his life, but a complete negligence of himself gave rise to a fatal sickness which swept him away from a large and respectable family, young and caring wife and a small child. Mr. L’s brilliant qualities will be missed by a large circle of friends.”[10] The Epitaph This sense of wasted potential is echoed in the poignant tablet his family erected at his grave. After close study of the tablet, as well as all past transcriptions of it, this is the epitaph carved for André Valsin Labarre:  Ci Gît un malhereux qui fut victime de son imprudence. Passant, verse une larme sur sa tombe, il n’avant que vingt sept ans. André Valsin Labarre Né aux Chapitoulas le 15 Decembre 1798 Decedé le 14 Aout 1826 Here lies an unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Passerby, shed a tear upon his grave, he was only twenty seven years old. André Valsin Labarre Born at Chapitoulas December 15, 1798 Died August 14, 1826 Labarre’s tablet was carved by Jean Jacques Isnard from gray marble. Isnard (1779-1859) was one of the earliest stonecutters in New Orleans. His prolific work can be found throughout St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Valsin’s death and burial in 1826 was the end of a short, but presumably happy life. His cause of death will likely remain a mystery. “Indiscretion or Excess” The phrase “victim of one’s own imprudence,” appears in rather specific narratives in the nineteenth century. It suggests a negligence of self-care by way of excessive living or failure to treat illness in its preliminary stages. For example, a woman who dies of consumption because she did not treat a cold was a victim of her own imprudence. Alternatively, the term “victim of imprudence” was frequently used in advertisements for men who had contracted venereal disease. In the case of Labarre, others have suggested perhaps the excesses of drink, although no record can confirm. For whatever reason, Valsin’s family requested such language for his tablet. Little would they know that the words they paid Isnard to carve would become somewhat of a legend a century later. A Travelling Tablet Perhaps the greatest mystery of all, however, is where Valsin himself was originally buried. A survey completed in the 1930s notes the tablet to be located in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, Aisle 8-R, although it does not specify lot number. Today, Valsin’s tablet is located in Aisle 7-R. Unfortunately, the original cemetery records for 1826 do not specify lot number. While we may love Valsin’s immortal eulogy, his mortal remains may never be located for sure. One Hundred Years of Mistranslation Nearly 75 years after Valsin’s death, in 1900, the New Orleans Daily Picayune wrote a full-page piece on local cemeteries in honor of All Saints’ Day, November 1. This was a common annual occurrence in which newspapers would describe the scene at each cemetery, noting curious epitaphs or beautiful new tombs. With this article, Valsin’s memory was revived in a very peculiar way: On one old slab, almost defaced with age, is the inscription “Ci git un malhereuse qui fut victim de son imprudence. Verse un larme sur sa tombe, et un ‘De Profundis’ s’il vout plait,” por son ame. Il n’avait que 27 ans, 1798.” The translation reads: “Here lies a poor unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Drop a tear on his tomb and say if you please the Psalm, ‘Out of the Depths I Have Cried unto Thee, Oh, Lord’ for his soul. He was only 27 years old.[11] Three years later, on November 2, 1903, the Picayune printed the exact same paragraph in another All Saints’ Day article. This printing birthed two widely-repeated falsehoods regarding Labarre – that he had died in 1798 (the year he was born), and that the tablet had an additional line regarding a psalm, which it clearly does not. This misunderstanding would perpetuate itself, making scholars and authors truly the victims of their own imprudence. In 1919, a tourist brochure said of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1: “The inscriptions are in French, and many of them tell how he who sleeps beneath ‘fell in a duel, the victim of his own imprudence.[12]’” It is unclear if this is directly inspired by Labarre or perhaps another now-missing tablet. Unfortunately, even the most revered of New Orleans cemetery texts replicate to the Labarre myth. In one seminal 1974 book, the authors suggest again that Labarre’s is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, quoting the Picayune article. The text also muses that perhaps the poor fellow had died in a duel. From 1974 to 2004, three other publications cite this faulty article, each suggesting that it is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, and that the deceased had met his end in a duel. One insists that the tablet is long lost to history. All this time, André Valsin Labarre’s tablet has sit idly by as tour groups wind in and out of the cemetery aisles.

New Orleans cemeteries typically identify the owners of tombs by direct lineage. Through this lens, there are no descendants to claim care of the prodigal son’s tablet. Valsin’s son, Samuel Placide Labarre, married Emma Labranche in 1866. Their union produced one son, who Samuel named after his father, Valsin. Valsin Labarre died around 1890. There is no indication that he married or had children. Additionally, Virginia Conrotte remarried after Valsin’s death. She and her new husband, Daniel Gregoire Borduzat had at least four children. Unfortunately, the surname Borduzat appears nowhere in indexed cemetery records. If indirect relatives to Valsin Labarre remain, they have not reconnected with his burial place. Both the tablet to his memory and Valsin himself have become, in a sense, immortal for the most peculiar of reasons. Yet their fate remains suspended between the aisles of New Orleans' oldest cemetery, awaiting the next chapter in their story. [1] Stanley C. Arthur and George Campbell Huchet de Kernion, Old Families of Louisiana (New Orleans: Harmanson, 131), 98-104.

[2] Arthur and Campbell, 98. [3] William Reeves, De La Barre: Life of a French Creole Family in Louisiana (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1980), 79, 88. [4] Reeves, 88. [5] Reeves, 175. [6] Reeves, 119. [7] Probate inventory of André Valsin Labarre, New Orleans Public Library microfilm KR 308, Old Inventories, Vol. L, 1821-1832. [8] 1821 New Orleans directory, Louis Labarre, No. 14 Conti. [9] New Orleans will documents, New Orleans Public Library, VRD410, 1805-1833, Recorder of Wills, Vol. 4, 106. [10] La Courier de Louisiane, August 16, 1826, 2. Accessed via microfilm, New Orleans Public Library. Translation composite of a number of translations from French speakers, William Reeves, and Emily Ford. [11] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1900, 3. [12] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “In Old New Orleans,” from Travel, Vol. XXXII, No. 4 (Feb. 1919), 26. At the end of the main aisle in Square 1 of St. Louis No. 2 is a simple tomb with a low-pitched gable roof. Coated in modern cement and latex paint, it is difficult to determine much about its original appearance. Perhaps it was once coated in brightly-colored stucco, or its roof tiled in slate or terra cotta. Ironwork may once have enclosed its simple design. Without the fortunate discovery of an historic photograph, which is extremely rare, the elegant past of this tomb may never be known. But the de Armas tomb offers a hint to the scrutinizing eye. Its marble closure tablet is embellished with an ornate relief carving depicting a winged hourglass encircled with a floral wreath. The hourglass is surrounded by a snake eating its tail – the ouroboros – a symbol of immortality. Among the few depictions of the winged hourglass in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, this carving is by far the most detailed. Such a carving is indicative of a level of style and craftsmanship long faded from New Orleans cemeteries. At one time it was not alone in its ornamental beauty, but instead belonged to a rich landscape of beaded wreaths, draped urns, and weeping angels. Even today, the de Armas tomb is not alone in one regard. Nearly three miles away, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2’s younger sister, St. Louis No. 3, stretches along the edge of Bayou St. John in long aisles. Amidst its large lots and photogenic tombs is the tomb of the Depaquier family. Uncompromised by modern repairs, the faded stucco walls bely that the tomb was once limewashed a dark rose color. The pitch of its roof is reminiscent of the de Armas tomb. The closure tablet of Dupaquier tomb is bordered with a carved braided rope. Atop its simply-lettered epitaph is a winged hourglass nearly identical to that found on the de Armas tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Studies of cemetery craftsmanship in New Orleans have shown that few motifs, materials, or methods in cemetery stonecarving are the result of happenstance. Who carved these tablets? What do they symbolize? And why did the Dupaquier and de Armas families end up owning identical tablets? The de Armas and Dupaquier Families The two tombs are the burial places of the patriarchs of their respective families. In St. Louis No. 2, Michel Theodore de Armas (sometimes listed in documents as Michael or Miguel), was a notary and lawyer who was born in New Orleans in 1783 and died in 1823.[1] In St. Louis No. 3, Claude Dupaquier was born in France in 1806, arrived in New Orleans in the 1840s, and died in 1856.[2] Between 1823 and 1856, life expectancy was around 37 years, so that these men died at age 40 and 50 (respectively) is unremarkable. Both de Armas and Dupaquier had children that became important members of New Orleans’ business and social circles after the Civil War. Dr. Auguste Dupaquier, who is buried with his parents, was described as having a “gentle, loving, and kindly temperament, mixed with firmness and rare energy, and he secured the affections of all whom he approached.[3]” Dr. Dupaquier had no discernable interaction with the children of de Armas, and it is unlikely that the families had enough relation to construct matching tombs knowingly. One significant similarity between the Michel de Armas and Claude Dupaqueir was their preference for the French language. Both tablets are carved in French.

In nineteenth century New Orleans, a person’s linguistic and cultural identity often determined who they chose to carve their final epitaph or build their eternal resting place. For de Armas, or his widow, Gertrude St. Cyr Debreuil, it would have been a given that they chose Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. New Orleans cemeteries are populated with the small, often overlooked signatures of local stonecutters. Often these signatures wear away, and craftsmen often neglected to sign their work at all. Many stonecutters began their careers working for other more established cutters, signing the name of their master instead of that of the apprentice. These realities complicate the study of cemetery craftwork. In the case of the de Armas closure tablet, a small, clean-lettered signature is present at its bottom right-hand corner – MONSSEAUX. The Depaquier tomb retains no signature at all. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux Like Claude Depaquier, Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux (1809-1874) was a French native who arrived in New Orleans as an adult.[4] Present in New Orleans by 1842, Monsseaux is best known as the stonecutter who built many tombs designed by architect J.N.B. De Pouilly. These included many famous tombs in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Monsseaux often worked with other stonecutters in either a master/apprentice role or as business partners. In addition to his work for J.N.B. de Pouilly, his signature is often found beside other cutters like Tronchard and Kursheedt & Bienvenu. Through his entire career, Monsseaux held the same marble yard on St. Louis Street at the corner of Robertson Street – directly beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 and New Basin Canal. Through his career, Monsseaux also sold marble to fellow stonecutters; he partnered with others to secure equipment and technology that advanced the trade. Most notably, he owned a steam marble works for some time in the 1870s, the rights to which he lent to other cutters Stroud and Richards.[5] Monsseaux’s accomplishments were many, but his clientele was rather distinct. Most of Monsseaux’s signed tablets are carved in French. In this manner, Monsseaux is a French counterpart for German-speaking stonecutters of the time who served a distinctly German clientele. There are always exceptions – Monsseaux built the DePouilly-designed Iberian Society tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Yet the majority of his work served French-speaking clients who belonged to the upper echelons of New Orleans society. Stylistic Inspirations and Symbolism French speaking upper-class New Orleaneans in the 1830s were enthralled with the style and beauty of tombs found in Paris’ Pere Lachaise Cemetery at the time, and Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux gladly catered to that demand. Sarcophagus-style tombs with corner acroteria and inverted torches appeared in St. Louis No. 2 during this time. These tastes adapted through the 1850s and into the first years of St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. Greek Revival temples and Egyptian Revival tombs rose in the squares of the both cemeteries, mimicking the aisles of the great French burial ground. Often, it was Monsseaux who provided his clients with these romantic sepulchers. Pere Lachaise Cemetery is populated with hundreds of winged hourglasses. In fact, the first image to greet the visitor at the cemetery gate is a pair of such hourglasses. This is also the case at Montparnasse Cemetery, also in Paris. The history of the winged hourglass as a funerary symbol appears to split along linguistic and cultural lines in the United States. In the English-speaking Northeast, it is contemporary with the skull-and-crossbones and death’s head, symbolizing the fleetingness of time. In this context, the winged hourglass was contemporary to the 18th century and faded from popularity by the 1830s. French-speaking New Orleans funerary culture developed more closely to that of Paris than its American cousins, however. The winged hourglass is seldom seen in tombs constructed prior to 1820. It does, however, appear to grow in popularity from 1820 through the 1850s, when the de Armas and Dupaquier tombs were constructed. This inspiration was drawn directly from the Parisian cemeteries. And New Orleans was not alone in this inspiration. Not to be outdone as a European city in the New World, Buenos Aires’ Recoleta Cemetery, founded in 1822, hums with the flutter of winged hourglasses. The de Armas and Dupaquier families may never have known each other, but they are together twin scions of a lost cemetery landscape. Opulent with their floral wreaths and outspread wings, their hourglass tablets were likely carved by Monsseaux himself or an apprentice. It is possible, even, that the Dupaquier tablet was a replica of de Armas’, carved by a student still learning his trade. Or, perhaps, both designs were borrowed from a pattern book imported from Paris. In any case, they endure as silent reminders of the importance of each tomb in the larger landscape of our historic cemeteries. [1] Florence M. Jumonville, Ph.D., ‘Formerly the Property of a Lawyer’: Books that Shaped Louisiana Law. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Library Facility Publications, 2009, 7.

[2] Orleans Death Indices 1804-1876. Vol. 17, 312. [3] “Death of Dr. Dupaquier,” New Orleans Daily Democrat, April 8, 1879, p. 8. [4] Charles LeJ. Mackie, “Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux: Marble Dealer,” printed in SOCGram, Fall 1984, 14-16. [5] Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly