|

Or, how to get rich in cemetery sales without really trying. Community mausoleums – multi-vault, mostly indoor structures that house dozens or hundreds of burials – are ubiquitous in the American cemetery landscape. Today, many that have survived are historic structures. But in their day, they were controversial, revolutionary, modern, and exploitative. In this series, we examine the two periods of community mausoleum construction in the United States, beginning with the 1907-1940 wave of popularity, and revisiting the subject in their mid-twentieth century renaissance. In both parts, we will examine New Orleans’ role in the community mausoleum movement. In their time, they were exalted as sanitary, “better way,” a “civilized” mode of burial, while their opponents in the cemetery and monument industries called them “mud houses,” “menaces,” and even “tenement vaults.[1]” They were Neoclassical, Art Deco, Gothic Revival, and even chimeras of architectural design. They were the objects of sales speculation as well as sources of affordability in American cemeteries. They were community mausoleums, and hundreds if not thousands of them survive in the American cemetery landscape today. Beginning in 1907 in Ganges, Ohio and ending in Atlanta, Georgia in 1943, the community mausoleum movement of the early twentieth century embodied changes in the funeral industry, advertising, economics, and the way Americans understood death itself. In New Orleans, only one cemetery can lay claim to part of this movement. Hope Mausoleum on Canal Street is the Crescent City’s only answer to the early community mausoleum, although its founders may have disputed that label. Yet, like other community mausoleums, Hope Mausoleum offered the public a novel kind of cemetery, one that it may not have even known it wanted.

Once jacks-of-all-funerary-trades who provided funeral carriages, caskets, tombs, and epitaphs, undertakers saw their embalming trade rise from an unusual curiosity to a staple of death care. This increase in embalming demand was augmented by new attitudes in American culture regarding hygiene and sanitation, as well as the increased power of the advertising and cemetery industries. The focus of Americans on sanitation and hygiene at the end of the twentieth century can only seldom be underestimated. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, medical science leapt forward – arcane theories of bad air or “miasmas” causing disease were scrapped for germ theory, which stated to the common person that cleanliness really could mean healthfulness. This belief was translated to the preparation of a deceased body by embalmers: the body was unclean, even contagious, and embalming could wash it free of contaminants.[3] Naturally, demand for embalming increased. In coming decades, the fixation on the cleanliness, free of putrefaction, of the deceased body would establish a ready market for community mausoleums.

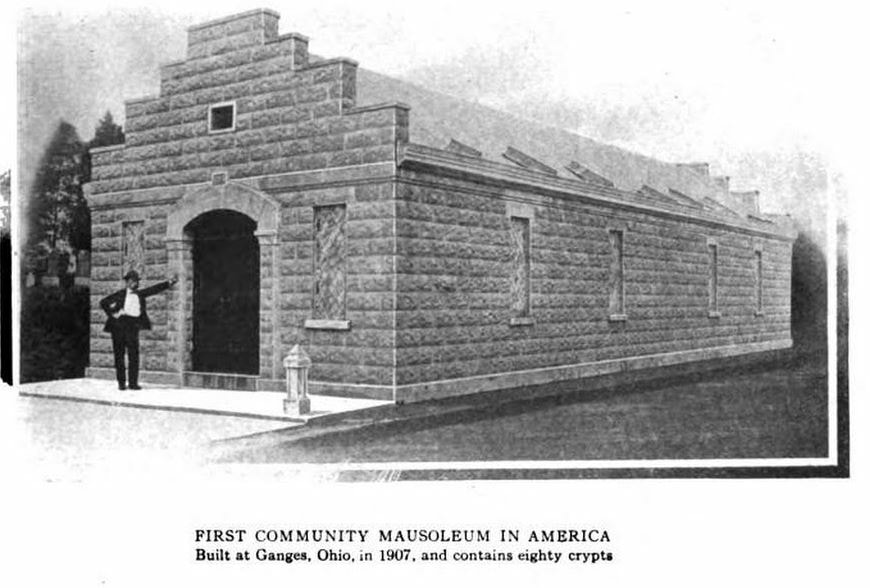

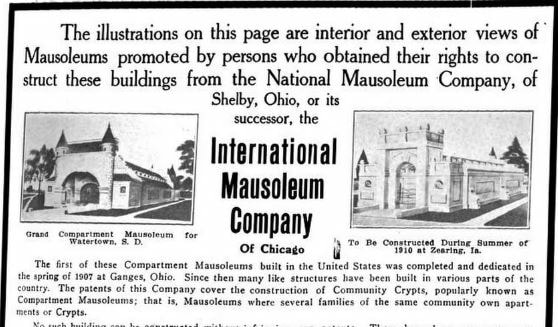

Travelling Salesmen, Speculating Mausoleum Companies, and Midwestern Cemeteries In 1900, William Ira Hood was forty years old, living in Lyme, Ohio with his wife Sarah and their children.[4] He had grown up on a farm but in his adulthood had picked up the professions of travelling salesman and inventor. He moved around a lot, through different counties in Ohio and sometimes travelling to Indiana and Illinois. It’s unclear how William I. Hood got the idea for the first community mausoleum. Given the age in which he lived and his profession, inspiration could have arisen from any number of places. In any case, Hood joined with a number of partners in Shelby, Ohio, to form the National Mausoleum Company of Shelby, Ohio in 1907 and completed the Ganges Mausoleum in Richland County, Ohio, that year. The business model was speculative and designed for profit. National Mausoleum Company would approach a cemetery owner (typically a private association or municipality) and agree to construct a multi-vault mausoleum of the most up-to-date engineering and design. In return, the cemetery association would pay a percentage of the vault sales to the mausoleum company. The company would advertise to the town’s citizens the benefits of above-ground, indoor community sepulture: it was as affordable if not cheaper than traditional in-ground burial; it was civilized and ensured the sanctity and cleanliness of the interred body. Communities throughout the Midwest bought in, hiring National Mausoleum Company to lease its protected patents for community mausoleums, and completing several in its first year. Yet the gimmick of community mausoleum construction and sales only worked if enough vaults were sold, especially those sales that took place before the mausoleum was even completed. Per Hood’s approach, the community mausoleum was a speculative game which, in many cases, left no funding left over for maintenance. Sometimes it left no funding to finish the building at all. In 1908, National Mausoleum Company obtained the contract to build a mausoleum in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois. It had gained the contract using the advertising techniques that stoked fear of the grave and hope for “a better way”: We, a group of men thoroughly convinced of the revolting conditions of ground burial, have started the great movement of “Mausoleum Entombment” throughout our country, that has awakened the people to the dangers and horror of ground burial.. (Quoted from Sangamoncountyhistory.com) Unfortunately, in the case of Oak Ridge Abbey, Hood’s projections of vault sales in the thousand-crypt Oak Ridge Abbey Mausoleum fell short of reality. The strain exacerbated National Mausoleum Company’s debts elsewhere in the Midwest. National Mausoleum Company was near bankruptcy before Oak Ridge Abbey was even completed in 1910, and the cemetery board of managers had to assume ownership without the promised return.[5] Hood and his partners landed on their feet after the bankruptcy by dissolving National Mausoleum Company of Shelby, Ohio, and reorganizing as International Mausoleum Company of Chicago. Hood’s health, however, failed. He died of kidney disease on December 13, 1911. He was buried in a National Mausoleum Company mausoleum in Kankakee, Illinois. Despite the scheme’s apparent volatility, entrepreneurs would follow Hood’s model, often paying National Mausoleum Company tens of thousands of dollars for the use of Hood’s patents.[6] In 1911, the South Dakota Mausoleum Company advertised to the people of Watertown that the modern mausoleum marks the only step that has ever been taken by civilized people to make their care of the dead superior in any way to the customs of uncivilized nations and tribes; in fact the burying of the dead in the damp, unprotected ground is less sanitary than the methods of some of the people whom we are accustomed to consider savages. The time is at hand for a more Christian civilized and conservative era of burial.[7] Mount Hope Cemetery Mausoleum was indeed built and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places today. Another copycat mausoleum company, this time in Iowa, would not have such luck. The Glendale Abbey Mausoleum in Des Moines was built by Waterloo Mausoleum Company in 1912. By 1915, the company had still not recovered its construction expenses, and the city of Des Moines assumed its ownership. As of 2015, preservationists still struggle to save the old mausoleum. As financial issues mounted in Des Moines, Waterloo Mausoleum Company ran into additional trouble in the town of Manchester, Iowa, where construction on its community mausoleum in Oakland Cemetery halted completely. The lumber firm contracted to build the mausoleum had not been paid and sued the company. The half-finished mausoleum was called an eyesore in 1916 when it was sold at a sheriff’s sale and ultimately demolished.[8] Cecil Bryan, the Mausoleum Man The first community mausoleums were not the triumphs of design that later mausoleums would embody. They were vernacular at best, and gaudy at worst. Where later mausoleums would be subtle, even elegant in their design, the mausoleums at Ganges, Watertown, Zearing Iowa, and Morca Illinois, for example, appeared to be overwrought interpretations of ancient artifices. Some looked like Medieval castles. Others were clunkily-understood iterations of the Romanesque revival that architect Henry Hobson Richardson popularized at the time. Around 1913, as community mausoleums spread through the Midwest and into the Pacific Northwest, the architectural ambitions of the movement were advanced by a single man, architect Cecil E. Bryan. In his career with the National Mausoleum Company, he designed at least eighty mausoleums of higher and higher style. His career originated with employment under both Frank Lloyd Wright and Ralph Modjeski, both of which pioneered the utility of reinforced concrete into modern architecture. Bryan brought this knowledge to the cemetery. His designs brought contemporary refinement and an understanding of construction materials to the previously-unwieldy appearance of community mausoleums. Bryan’s architecture furthermore evoked the permanence and romanticism of historic mausoleums – the pyramids, Hadrian’s tomb, the Pantheon. In his brochures, Bryan compared the architecture of the ages with community mausoleums, as well as contemporary feats of funerary design like Grant’s tomb and the McKinley National Memorial.[9] Bryan’s early mausoleums were imposing in their external simplicity. By nature of their function, community mausoleums were long, wide buildings. Bryan designed these buildings with a central entryway that projected from the façade, ornamented with Neoclassical, Egyptian Revival, or Romanesque motifs. To the sides of these central edifices were the mausoleum’s monolithic wings, often devoid of ornament beyond cornicework or fenestration. This phase of Bryan’s designs can be seen in Beecher Mausoleum (1914), Hamilton Mausoleum (1914), Modesto, California’s Pioneer Cemetery/Odd Fellows Mausoleum (1914), and Forest Lawn Mausoleum (1919), among many, many others. As the community mausoleum movement moved westward and found a ready market in California, Bryan adopted Spanish colonial and Gothic revival into his repertoire, with Mountain View Mausoleum in Altadena (1923) among his crowning designs. Bryan, who died in 1951, would design at least eighty community mausoleums in at least nine states. Like William I. Hood, he was buried in one of his own mausoleums – Mountain View in Altadena. His final design, Westview Abbey Mausoleum in Atlanta, Georgia (1943), was a magnum opus of concrete work. Far from simple and monolithic in its edifice, the primary façade of Westview is a cacophony of Moorish and Spanish-revival filigree, turrets, turned columns, porticos, and niches. Mausoleum Versus Monuments While many customers of the mausoleum companies may have been pleased with their investments, there was one group of Americans who thoroughly eschewed the movement – American monument companies. As early as 1911, industry circulars for monument and memorial companies decried community mausoleums as “mud houses” peddled by a “carpet bagger evil.”[10] The Association of American Cemetery Superintendents in 1913 reiterated this opposition, calling community mausoleums exploitative: [there are] grave dangers in a contract between a cemetery association and an outside corporation by which the latter concern agrees to erect and exploit such a structure, reimbursing itself from the first proceeds of the sale of crypts, agreeing to turn over to the cemetery association what is left after it has satisfied its own demands, and is ready to pass on and exploit some other community in the same manner[11]

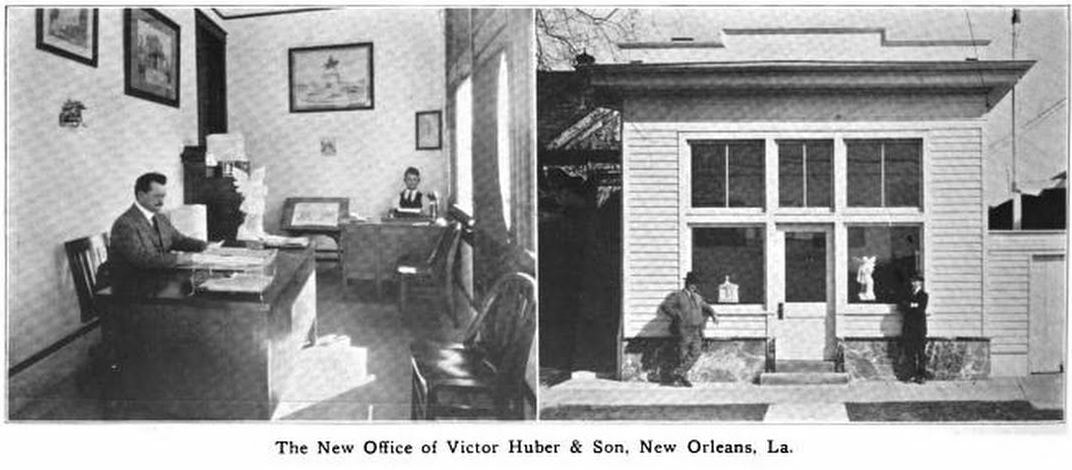

Monument dealers at this time were often cemetery owners or operators themselves. It is no surprise that their understanding of their industry as established, traditional, and safe was disrupted by the community mausoleum. When community mausoleum salesmen came to town, monument dealers advertised against them. One trade magazine suggested monument dealers increase advertisements for private mausoleums. Private mausoleums, the magazine reasoned, were what customers really wanted. If only they were advertised with the same energy as community mausoleums, monument dealers might recapture that share of the market.[14] In an odd turn, the model of the traditional New Orleans tomb had a brief moment of popularity in these discussions. In a ten-part essay series in the trade magazine Design Hints for Memorial Craftsmen running from 1929 to 1930, the New Orleans tomb was pitched as an affordable, sales-lucrative alternative to the public and private mausoleum. Said the authors, New Orleans tombs with their simple design, lack of walk-in vestibules, and affordable building materials, could be the answer to monument dealers’ prayers. They were cheap to make, attractive to sell since they resembled affluent private mausoleums, and could finally combat the “community mausoleum evil.[15]” “The New Orleans Tomb” series covered tomb construction using poured cement and granite enclosure tablets, as well as how to design below-grade ossuary spaces. But possibly its most fascinating discussion is one of ventilation. The New Orleans tomb is self-ventilating, claimed the authors, whereas community mausoleums were vented only by new-fangled innovations which were sure to fail. Said the authors with a sneer and no shortage of late 1920s lingo: … Ventilation of above-ground sepulchral structures is a much argued question. It is a question that has caused our friends the community-vault builders many sleepless nights. You can hardly find a promoter of community vaults who hasn’t at least one patent on the ventilation of vaults and generally the patent is about as impracticable and as perfectly useless as a flagpole sitter’s record. That community vaults present a far greater problem in ventilation than the private mausoleum or a small tomb is a fact; goodness knows that even with the fandangles built into some community vaults they still smell a bit – er – stale, to say the least.[16] Colorful language aside, the authors of “The New Orleans Tomb,” written so passionately against the community mausoleum movement, may have protested too much. They knew the limitations of ventilation in New Orleans tombs when using modern cements. But even moreover, their anti-mausoleum stance was ironic. At that very moment, they themselves were building New Orleans first community mausoleum – Hope Mausoleum Victor Huber and Hope Mausoleum “The New Orleans Tomb” series was written by Leonard V. and Albert R. Huber, two sons of monument dealer Victor Huber (1876-1941). By the time of its publishing (1929-1930), the Huber family had already begun construction on Hope Mausoleum, but their story begins two decades earlier. Victor Huber was a German-born stone cutter who began work in New Orleans in 1909. At this time, New Orleans stonecutting had shifted from a hyper-local cottage industry to a nationwide network of dealers and agents. In New Orleans, Albert Weiblen pioneered this model, but many others followed suit, including Huber. In 1923 Huber moved from his small Mid-City office to a custom building at 136 South Solomon Street which he designed in partnership with his son, Leonard Victor Huber.[17] They wouldn’t stay there for long, though, and moved to 5055 Canal Street in 1926.[18] The new Canal Street building (which now houses the Herb Import Company) was itself a demonstration of what modern concrete could do – the shop was an elegant building with a vaulted parapet with trifoil and quatrefoil inlays. Victor Huber spent most of the decade building tombs primarily in Metairie and Greenwood Cemeteries, selling them to private citizens through his storefront or via newspaper advertisements. In the late 1920s, all religious cemeteries belonged to their respective parishes. The St. Louis cemeteries belonged to St. Louis Church, St. Patrick Cemeteries to St. Patrick Cathedral, and so on. For the Catholic cemeteries, this changed in 1964 with the formation of New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. For the German Evangelical Lutheran church and its cemetery, St. John Cemetery, the transfer of ownership came much earlier. By 1929, St. John Lutheran Church sought to sell its cemetery due to mounting tax bills. According to Leonard Victor Huber, his father purchased the cemetery from the congregation, of which he was a member. Now in possession of a sixty-two-year-old cemetery, Huber sought to turn a profit from the property, mainly by building individual tombs and selling them to families. This was the case until 1930, when construction began on Hope Mausoleum.

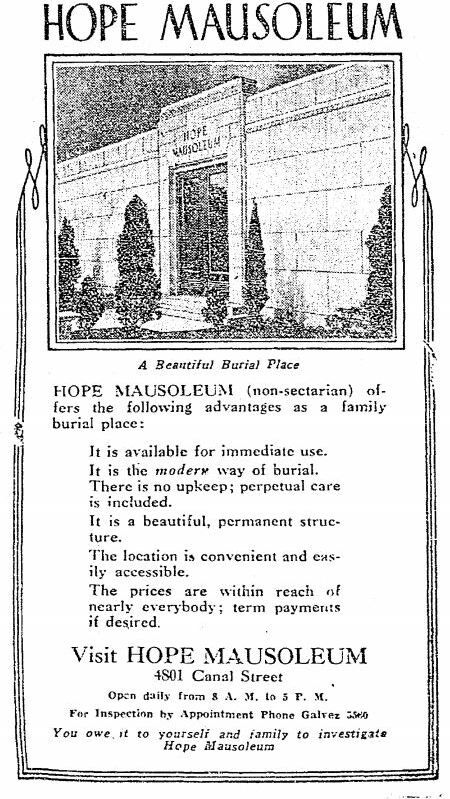

Instead, Hope Mausoleum was advertised as permanent. In nearly daily advertisements in local New Orleans papers, Hope Mausoleum was touted as “The Modern Way,” in which all vaults were under perpetual care, free of any maintenance needs. The maintenance argument may have been the closest the Hubers came to condemning New Orleans’ “old” way: traditional New Orleans tombs required annual maintenance to remain in good shape. Hope Mausoleum promised to relieve families of this burden.[20] Hope Mausoleum was expanded several times and now contains more than 8,000 burial vaults. It also houses the first crematory to be constructed in Louisiana, which opened in 1971.[21] While its exterior travertine walls have weathered over time, its interior remains as pearl-white and well maintained as in its heyday. While access to the mausoleum is unusually restrictive – only family members are permitted to enter and photography is not permitted – the mausoleum has persevered into the present as cared-for and utilized as it was at its inception. Such is the case for many community mausoleums. Many are now on the National Register of Historic Places, treasured as historic sites. Many others, however, did not survive such a test of time. In our next post, we will explore the second half of the community mausoleum movement as well as how community mausoleums are managed and preserved today. [1] “A Mausoleum,” Madison Daily Reader (Madison, South Dakota), August 9, 1911, 3; “Mausoleum,” Daily Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), 7; “Abbey Mausoleum,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), November 12, 1929, 9; Harvey R. Kruse, “Advertise the Private Mausoleum Now, - While the idea is popular,” Design Hints for Memorial Craftsmen, Vol. 6, No. 8 (February 1930), 8; Merrill Schaefer, “When is a Community Mausoleum Not a Community Mausoleum?” Granite, Marble, & Bronze, Vol. XXIV, No. 5 (May 1914), 28; “Cemetery Notes,” Park and Cemetery, Vol. XXIII, No. 2 (April 1913), 125.

[2] Philippe Aries, The Hour of Our Death (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc, 1981), 409. [3] Stephen Wickes, Sepulture: Its History, Methods, and Sanitary Requisites (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co., 1884), 55, 117; Wm. N. Attwood, “The Physician and the Undertaker,” The Annals of Hygiene, Vol. X, No. 1 (January 1895), 480-483. [4] United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900 (Washington, DC: NARA, 1900), T623, 1854 rolls. [5] Edward J. Russo and Curtis R. Mann, Oak Ridge Cemetery (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009), 79. [6] “Note Given for a Patent Right Must be Marked,” The Banking Law Journal, Vol. XXXII (Jan-Dec 1915), 844. [7] “A Mausoleum,” Madison Daily Reader (Madison, South Dakota), August 9, 1911, 3. [8] “Mausoleum is Sold at Sheriff Sale,” Manchester Democrat (Manchester, IA), April 11, 1917, 1. [9] Cecil E. Bryan, Inc., Community Mausoleums (Chicago: Cecil E. Bryan, Inc., 1917), 20-21. [10] Merrill Schaefer, “When is a Community Mausoleum Not a Community Mausoleum?” Granite, Marble & Bronze, Vol. XXIV, No. 5 (May 1914), 28; “Convention of the National Retail Monument Retailers Association of America, Inc., August 18-22,” Granite, Marble & Bronze, Vol. XXIV, No. 5 (May 1914), 14. [11] “Cemetery Men Oppose Community Mausoleums,” Park and Cemetery, Vol. XXIII, No. 2 (April 1913), 159. [12] Harvey R. Kruse, “Advertise the Private Mausoleum Now, - While the idea is popular,” Design Hints for Memorial Craftsmen, Vol. 6, No. 8 (February 1930), 8. [13] Bryan, Inc., Community Mausoleums, 1. [14] Harvey R. Kruse, “Advertise the Private Mausoleum Now, - While the idea is popular,” Design Hints for Memorial Craftsmen, Vol. 6, No. 8 (February 1930), 8. [15] Leonard V. and Albert R. Huber, “The New Orleans Tomb, Part I,” Design Hints for Memorial Craftsmen, Vol. 6, No. 4 (October 1929), 14. [16] Leonard V. and Albert R. Huber, “The New Orleans Tomb, Part VIII,” Design Hints for Memorial Craftsmen, Vol. 6, No. 11 (May 1930), 10. [17] “Modern New Orleans Plant,” American Stone Trade, Vol. XXIII, No. 9 (April 1923), 18. [18] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory 1926, Vol. LIII (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., 1926), 760. [19] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, and Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 47. [20] “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, April 14, 1932, 2. [21] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 48; “Crematory is Installed,” Times-Picayune, January 27, 1971, 16.

2 Comments

10/20/2021 10:37:11 pm

Thanks for sharing such an informative blog. Porous texture with deliberate pin and bug holes. Travertine wall panels create a subtle yet dramatic appeal at indoor and semi indoor spaces. Elements and holes are randomly infused on the texture during the manufacturing process to create an unrefined feel which effortlessly blends into the contemporary style of design. As I came across your blog and found it very useful, I would like you to visit this article and share your valuable comment : https://bit.ly/3aUPO6X

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECTNew Orleans, Louisiana

restoration@oakandlaurel.com (504) 602-9718 |

Proudly powered by Weebly