|

Irish-born Hagan was a state senator, a stonecutter, a real estate developer, and a dock commissioner in his long life, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was deeply shaped by his work. Along the main aisle of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, a pink granite tomb stands out from its lime-washed, marble-clad neighbors. Surrounded by a cast-iron fence, the tomb of James Hagan and John Henderson is often noted as the last resting place of a stonecutter whose work is prominent elsewhere in the cemetery. Yet this note, and the carved name of James Hagan, is only one small detail in the larger story of James Hagan’s life. James Hagan was not only a stonecutter but a real-estate dealer, state senator, community leader, and politician. He lived and worked in New Orleans not only in a time of great social change but a period of high craftwork and architecture in the city’s cemeteries. Among his signed works are some of the most ornate in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, all marked by detailed stonework and expensive marble cladding.[1] Sources suggest that James Hagan built the pink granite tomb not for himself but for his first wife, Mary Henderson, after her death in 1872. Hagan married Mary Henderson in New Orleans shortly after he immigrated from County Armagh or County Antrim, Ireland, in approximately 1852.[2] James Hagan and his brothers John, Peter, and Patrick, as well as their mother, all fled Ireland in the 1850s after famine likely forced them to emigrate. In the Fourth District of New Orleans, formerly the New Orleans suburb of Lafayette, the Hagans joined thousands of other Irish who had formed a community along the banks of the Mississippi River in the neighborhood now known as Irish Channel.

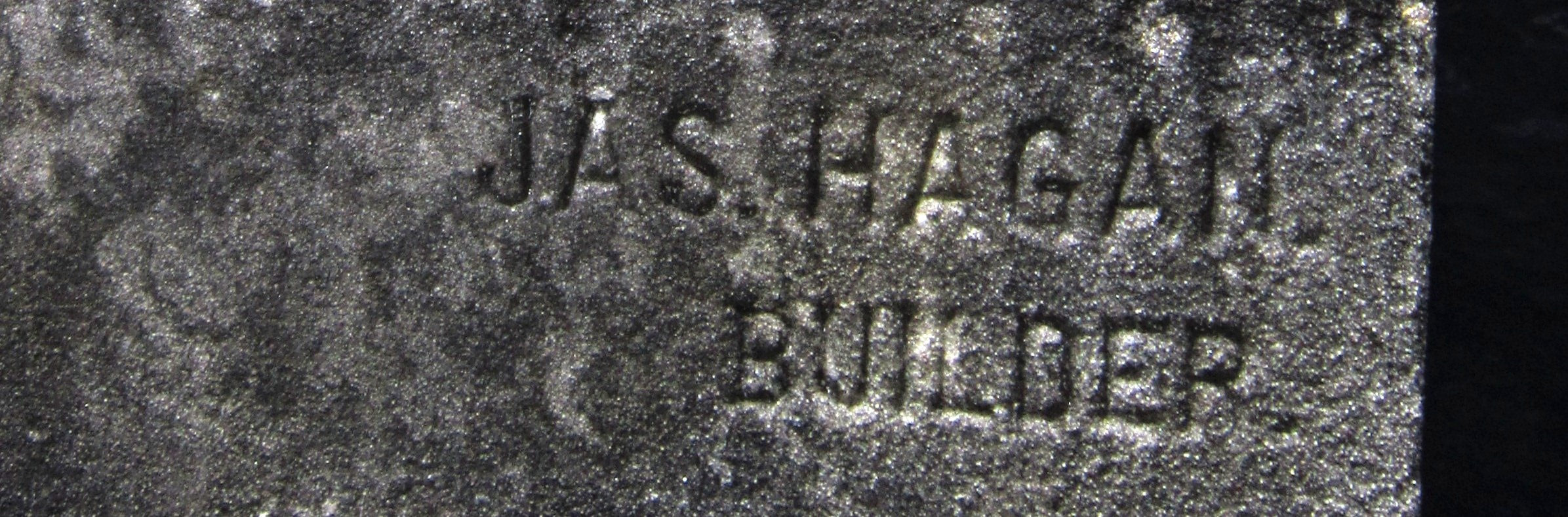

Builders and others interested will find at Mr. Hagan’s Marble Works, corner of Prytania and Washington Streets, marble of every description, German and North river flagging, cement, lime, plaster, fire and lake brick, sand, shells, etc., etc., at the lowest market price and of the very best quality. Mr. Hagan has constantly employed the most competent workmen, and is prepared to make, to order, in the most artistic manner, any style of tomb, mantle or grate.[7] The community of funerary craftsmen to which James Hagan belonged was tied to the stylistic period of the 1850s to 1860s, an age in which high-style motifs were borrowed from European cemeteries such as Père Lachaise in Paris. Hagan and his contemporaries D.F. Simpson, Anthony Barret, H. Lowenstein, and Creole/French stonecutters Florville Foy and Paul Hyppolyte Monsseaux, borrowed design attributes from their French counterparts.[8] Sarcophagus tombs with canted sides, massive cross-gable roofs, inverted torch symbolism, scrollwork, and acroteria signified their work. This style is directly attributed to New Orleans architect Jacques Nicolas Bussière de Pouilly, who designed many such tombs in St. Louis Cemeteries Nos. 1 and 2.[9] Hagan’s more distinctive tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 – the VanBenthuysen, Sewell, Peirce, Randolph, and Auch tombs – exemplify this style. By the mid-1870s, the classical style of tomb would give way to a new aesthetic that ignored the Greek Revival-inspired, labor-intensive artisanship of previous decades. In the 1850s and 1860s, even the simplest tomb was built with a Classical, triangular pediment and gable roof. By the late 1870s, artisans like J. Frederick Birchmeier, Joseph F. Callico, and Hugh J. McDonald were constructing double-vaulted tombs with barrel roofs or Gothic-inspired wall-gable parapets. It appears that James Hagan kept in step with this transition. On All Saints Day, 1878, the Daily City Item referred to his late wife’s tomb as a “new departure in style and design in construction,” although the granite tomb was a departure even from the new stylistic norm.[10] Like many other stonecutters and tomb builders in New Orleans, James Hagan additionally sold building supplies like flagstone, lime, cement, and plaster from his marble yard. He became, as many of his contemporaries did, a contractor for new building projects. In 1874, he oversaw the construction of St. Patrick’s Hall on Lafayette Square, where he eventually moved his marble office.[11] In 1880, he was elected the Democratic state senator for Orleans Parish.[12] Over the course of his single term of service, he mostly served on committees concerning the restoration of the state Capitol at Baton Rouge. He is remembered in documentation as having fought obstinately against nearly all decisions made on the project; he eventually completely abstained from voting.[13] By 1898, James Hagan ceased advertising his marble business. He was appointed Deputy Dock Commissioner by 1900, a token political appointment given to a nearly seventy year-old man. Although he had remarried in 1874, his new wife, Mary Rebecca Randolph, died in 1904. She was interred into James Hagan’s Lafayette No. 1 tomb, beside Hagan’s first wife Mary Henderson.[14] In his last years, James Hagan suffered a long illness and was cared for by his daughter, Mary Clara, who appears never to have married. He died on February 27, 1908, at the age of seventy-eight, having survived his two wives, his brothers (Patrick died of yellow fever in 1878, John died in Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1891), and one of his sons. His son by Mary Rebecca, named Randolph, returned from his home in New York to handle James Hagan's funeral and burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, where he rejoined many of his family members that went before him. At some time in the 1920s, the closure tablet that bears his name was re-carved and replaced by then-sexton Edward Alfortish.[15] James Hagan’s life was an illustration of the Irish immigrant experience in New Orleans, representing aspects of Reconstruction politics and the development of the city’s geography and cultural identity in the second half of the nineteenth century. His work remains as some of the most visually stunning in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. That his own tomb remains so distinctive within the cemetery’s landscape is fitting. It represents the end of a long and productive life of service to the city and its cemeteries. [1] A total of sixteen tombs and tablets in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 retain the signatures of James Hagan. An additional two lots bear signatures of his brother, John Hagan. Based on a 2012 survey of all signed craftwork in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1.

[2] “James Hagan’s Death,” Times-Picayune, February 28, 1908; Frank Bordelon, Descendants of John Hagan (n.p. 2013). [3] Parish of Orleans, Office of Conveyances and Mortgages, Abstract Book 118, Page 818; City of New Orleans, Notarial Archives Division, Bendernagle, Vol. 15, Act 297; Parish of Orleans, Office of Conveyances and Mortgages, Abstract Book 135, Page 521; Book 122, Page 736; Book 99, Pages 648-649; Book 103, Page 287; Book 104, Page 311; Book 103, Page 325; Book 129, Page 289; Book 135, Page 521, to cite a few of Hagan and Henderson’s transactions. [4] Gardener & Wharton’s New Orleans Directory for the Year 1858 (New Orleans: Wharton’s Steam Book and Job Printing, 1858), 143. In this year, James and John lived together on First Street, between Dryades and St. Denis (present day Danneel Street). [5] “Names of the Drafted,” Daily Picayune, April 29, 1865, 6. [6] Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1866 (New Orleans: True Delta Book and Job Office, 1866), 210; Parish of Orleans, Office of Conveyances and Mortgages, Abstract Book 91, Page 75; Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84, 40; Graham’s Crescent City Directory for 1867 (New Orleans: A. Graham, 1866), 571. [7] “Lafayette Marble Works,” New Orleans Crescent, January 9, 1869, 2. [8] D.F. Simpson was active as a craftsman in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from 1863-1868; Anthony Barret 1855-1874; H. Lowenstein 1861-1869; Florville Foy 1841-1902; P.H. Monsseaux 1851-1873. Based on a survey of historic directories. [9] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly” (MA Thesis, Tulane University, 1992), 48-52. [10] “All Saints Day,” Daily City Item, November 1, 1878, 1. [11] “Laying of the Corner Stone of St. Patrick’s Hall,” The Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, March 22, 1874, 5; “St Patrick’s Hall, Opening Night – General Description, the Founders and Builders of the Hall,” The New Orleans Times, December 12, 1874, 3; Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1879 (New Orleans: L. Soards Publishing Co., 1879), 329; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1880 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1880), 362; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1882 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co., Publishing, 1882), 302. [12] Arthur E. McEnany, Membership in the Louisiana Senate, 1880-Present (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Senate, January 2012), 66. [13] “The Other Side: The Report Adopted by the State-House Commission Respecting the Work Done,” Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 28, 1880; Carol K. Haase, Louisiana’s Old State Capitol (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2009), 18, 22-23; Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 21, 1880, 5. [14] Times-Picayune, March 16, 1904. [15] “James Hagan’s Death,” Times-Picayune, February 28, 1908.

7 Comments

corey douglas

2/5/2019 09:16:37 pm

Loved the article!

Reply

7/22/2019 03:48:15 am

Thanks for informative share! I have never been to New Orleans Stonecutter. Hope to be there someday..

Reply

12/21/2019 04:32:45 am

Thank you Emily for sharing about such personality from the past. There are many names in the history who are not prominent but they certainly did a great work. James Hagan is one of those. I am glad you researched and informed all about him.

Reply

12/7/2021 12:36:05 am

I found this article very informative about "Capitol in Baton Rouge". Looking forward for more informative articles like this related to <b><a href="https://advanceddrivewaysolutions.co.uk/" rel="dofollow">Fencing & Resin Drives Solutions Blackpool

Reply

8/29/2022 10:34:18 pm

I just found your article about James Hagan. I'm a descendent of the Henderson side of the crypt. If you have any information about John Henderson, Jr. I'd love to hear it.

Reply

6/8/2023 10:10:11 am

"I found this article very informative about ""Resin driveways"". Looking forward for more informative articles like this related to <b><a href=""https://advanceddrivewaysolutions.co.uk/"" rel=""dofollow"">Advanced Driveway Solutions

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly