|

Earlier this month, the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority of Seattle, Washington, announced the planned removal of an estimated one million pieces of chewing gum from the “gum wall” at Pike Place. Located within one of Seattle’s primary tourist destinations, the wall has become tourist destination in and of itself. In 2009, it was declared the second “germiest” tourist destination in the world – just behind the Blarney Stone.

Prior to 1999, it would have been difficult for a casual tourist to know that part of the “Pike Place experience” was to stick used chewing gum on a wall. To be sure, some visitors accompanied by tour guides may have been regaled with stories of this unusual tradition. But without a tour guide the wall would nary have been touched with tourist gum. Guide books did not even include the gum wall until after 2008 – we checked. Alone, the gum wall doesn’t really illustrate much other than a gross and “quirky” tourist tradition. But seen through a lens of lipstick, locks, and tourism, it illustrates an issue all cities seeking to woo tourism dollars should take into account.

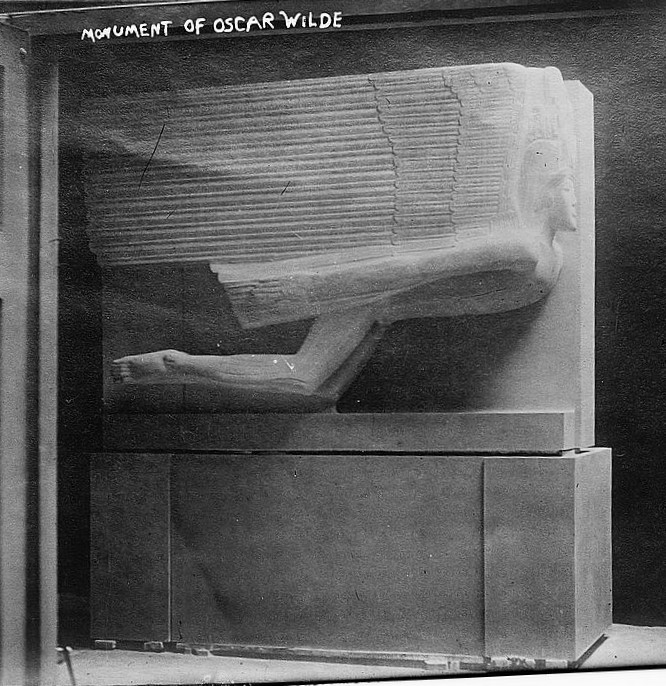

Installed in 1914, the sculpture (by Jacob Epstein, entitled The Sphinx) depicts an angel with male anatomy, which has been the target of mischief for nearly a century. Yet the worst threat to the sculpture arose much more recently. In the 1990s, it is reported, one lipstick kiss was placed upon the limestone marker. In the next twenty years, the load of lipstick marks on limestone became overwhelming, threatening to compromise the piece irreversibly. In 2013, this monument was the third-ranked germiest tourist attraction in the world. Thanks to efforts from the French and Irish governments amounting to more than €50,000, the statue was restored. A plexiglass barrier was installed around the burial place. At present, the plexiglass is inundated regularly with lipstick marks. For New Orleaneans, a lot of these seemingly unrelated local peccadilloes should sound very familiar. Each is a small act executed by tourists involving an easy-to-come-by medium: gum, locks, or lipstick. Many of these things travelers already have in their possession. They each have a somewhat weak background story connecting the tradition to the lure or the romance of the place. They each involve a literal way for an individual to “make a mark” on a place visited - to take part in something larger than themselves. They each began or expanded drastically after the late 1990s. Each of these traditions is innately destructive to historic and cultural resources. However romantic, fun, and exciting these traditions are, they amount to little more than participatory vandalism. All of these traditions have become part of travel-blog echo chambers which have fed the impression that the “tradition” is real and encouraged vandalism far beyond the useful life of click-bait entertainment. We would link to the hundreds of examples of “10 landmarks you must deface while in Paris,” but we work hard not to encourage that type of behavior. For sixty years, New Orleans had its own invented tourist tradition with which to contend. Beginning with a tourist brochure in the mid-1940s, the presumed tomb of voodoo icon Marie Laveau was repeatedly marked in accordance with a contrived wish-making ritual. The majority of these marks were created with similar items to those found in Père Lachaise – lipstick and pens. Although a constant presence in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 for decades, photographic documentation shows that the frequency of vandalism on the tomb increased after the late 1990s. Like Paris and Seattle, this phenomenon is likely related to the widened availability of “off the beaten path” tourism guides and social media resources online. While invented traditions are nothing new, the population of visitors who are likely to participate in them has grown enough that their impact is becoming increasingly difficult to manage. In 2014, New Orleans joined its Parisian counterparts in combating harmful participatory vandalism. The paired efforts of removing vandalism from cemetery property and restricting access to St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 resulted in a measurable decrease in tourist impact. Like Paris, interventions are often costly and can compromise historic resources with the introduction of protective materials (for example, plexiglass is not historic). Intervention can also require an immense investment of resources which may be needed elsewhere. In the moment, it is easy to perceive each incident of tourist “tradition” impact as isolated. Yet the recurrence of this phenomenon in tourism-driven economies proves they do not occur in a vacuum. Little research has been conducted that compares the similarities of such incidents from city to city, or the efficacy of treatment and prevention approaches. New Orleans is unique in so many ways, yet it faces the same difficulties of impact-management and preservation as any other tourism-based economy. It is time to closely examine the impact of perceived “traditions” and other behavioral cues on the preservation of our historic resources. Otherwise, it will not be long before one lipstick kiss snowballs into another expensive debacle. For other great insights on participatory vandalism and invented traditions:

NO LOVE LOCKS™ “No Love Lost on Love Locks,” Laura O’Brien “The Tipping Point Between Vandalism and Art,” Johana Desta, Mashable.com

2 Comments

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly