|

Earlier this month, the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority of Seattle, Washington, announced the planned removal of an estimated one million pieces of chewing gum from the “gum wall” at Pike Place. Located within one of Seattle’s primary tourist destinations, the wall has become tourist destination in and of itself. In 2009, it was declared the second “germiest” tourist destination in the world – just behind the Blarney Stone.

Prior to 1999, it would have been difficult for a casual tourist to know that part of the “Pike Place experience” was to stick used chewing gum on a wall. To be sure, some visitors accompanied by tour guides may have been regaled with stories of this unusual tradition. But without a tour guide the wall would nary have been touched with tourist gum. Guide books did not even include the gum wall until after 2008 – we checked. Alone, the gum wall doesn’t really illustrate much other than a gross and “quirky” tourist tradition. But seen through a lens of lipstick, locks, and tourism, it illustrates an issue all cities seeking to woo tourism dollars should take into account.

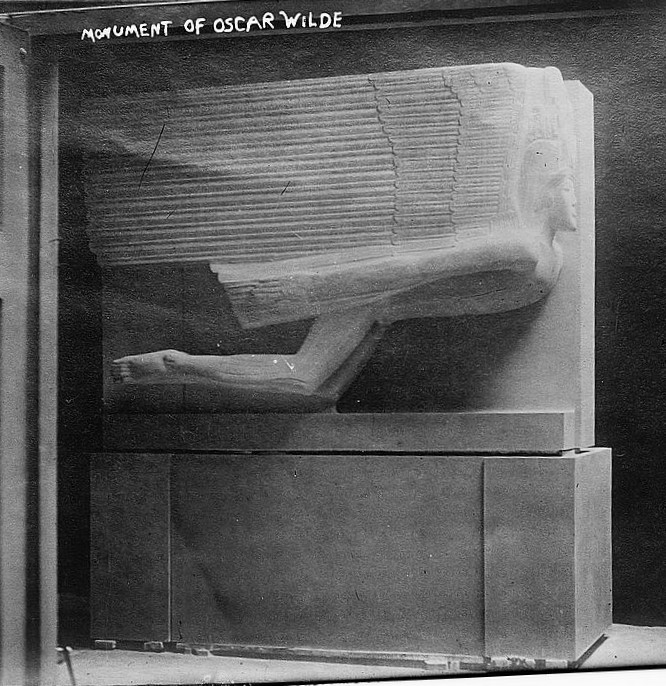

Installed in 1914, the sculpture (by Jacob Epstein, entitled The Sphinx) depicts an angel with male anatomy, which has been the target of mischief for nearly a century. Yet the worst threat to the sculpture arose much more recently. In the 1990s, it is reported, one lipstick kiss was placed upon the limestone marker. In the next twenty years, the load of lipstick marks on limestone became overwhelming, threatening to compromise the piece irreversibly. In 2013, this monument was the third-ranked germiest tourist attraction in the world. Thanks to efforts from the French and Irish governments amounting to more than €50,000, the statue was restored. A plexiglass barrier was installed around the burial place. At present, the plexiglass is inundated regularly with lipstick marks. For New Orleaneans, a lot of these seemingly unrelated local peccadilloes should sound very familiar. Each is a small act executed by tourists involving an easy-to-come-by medium: gum, locks, or lipstick. Many of these things travelers already have in their possession. They each have a somewhat weak background story connecting the tradition to the lure or the romance of the place. They each involve a literal way for an individual to “make a mark” on a place visited - to take part in something larger than themselves. They each began or expanded drastically after the late 1990s. Each of these traditions is innately destructive to historic and cultural resources. However romantic, fun, and exciting these traditions are, they amount to little more than participatory vandalism. All of these traditions have become part of travel-blog echo chambers which have fed the impression that the “tradition” is real and encouraged vandalism far beyond the useful life of click-bait entertainment. We would link to the hundreds of examples of “10 landmarks you must deface while in Paris,” but we work hard not to encourage that type of behavior. For sixty years, New Orleans had its own invented tourist tradition with which to contend. Beginning with a tourist brochure in the mid-1940s, the presumed tomb of voodoo icon Marie Laveau was repeatedly marked in accordance with a contrived wish-making ritual. The majority of these marks were created with similar items to those found in Père Lachaise – lipstick and pens. Although a constant presence in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 for decades, photographic documentation shows that the frequency of vandalism on the tomb increased after the late 1990s. Like Paris and Seattle, this phenomenon is likely related to the widened availability of “off the beaten path” tourism guides and social media resources online. While invented traditions are nothing new, the population of visitors who are likely to participate in them has grown enough that their impact is becoming increasingly difficult to manage. In 2014, New Orleans joined its Parisian counterparts in combating harmful participatory vandalism. The paired efforts of removing vandalism from cemetery property and restricting access to St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 resulted in a measurable decrease in tourist impact. Like Paris, interventions are often costly and can compromise historic resources with the introduction of protective materials (for example, plexiglass is not historic). Intervention can also require an immense investment of resources which may be needed elsewhere. In the moment, it is easy to perceive each incident of tourist “tradition” impact as isolated. Yet the recurrence of this phenomenon in tourism-driven economies proves they do not occur in a vacuum. Little research has been conducted that compares the similarities of such incidents from city to city, or the efficacy of treatment and prevention approaches. New Orleans is unique in so many ways, yet it faces the same difficulties of impact-management and preservation as any other tourism-based economy. It is time to closely examine the impact of perceived “traditions” and other behavioral cues on the preservation of our historic resources. Otherwise, it will not be long before one lipstick kiss snowballs into another expensive debacle. For other great insights on participatory vandalism and invented traditions:

NO LOVE LOCKS™ “No Love Lost on Love Locks,” Laura O’Brien “The Tipping Point Between Vandalism and Art,” Johana Desta, Mashable.com

2 Comments

Part Three of Three Brickmaking in the Late Nineteenth Century Expanding infrastructure and advancing technology led to a number of advances in brickmaking after the Civil War. These processes included dry-pressing, in which denser clay is compressed using steam-powered equipment, and extruding, in which the mold is abandoned for extruded clay cut with wires. In buildings, New Orleans saw entirely new materials like terra cotta and cast-iron storefronts. In New Orleans cemeteries, terra cotta was never established as a structural material. However, cast-iron companies like Wood, Miltenberger & Co. expanded their market by building catalog-ordered iron tombs. New Orleans has more than one dozen of these tombs remaining. In cemeteries, red river brick was almost entirely phased out, although many brickyards still produced them.[1] Many bricks found in tombs of this era show different variations in color, texture, and inclusions, but much are similar to “hard tans,” indicating sources in St. Tammany Parish. This is likely, as even more brickyards developed there after 1865.[2]  from the St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. Image courtesy Library of Congress. from the St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. Image courtesy Library of Congress. Among the St. Tammany brickyards to establish and grow in the late 19th century was St. Joe Brick Company. Founded in 1891, St. Joe Brick used (and still uses) wooden molds for brick manufacture. St. Joe bricks, are found throughout New Orleans cemeteries, where their porousness, dimension, and breathability suited tombs coated in lime stucco. Entire tombs were constructed using exclusively St. Joe Brick. Today, St. Joe bricks can still be purchased from the company’s Pearl River yard and other distributors. Like historic salvaged bricks, they mimic the qualities builders sought in historic building materials.[3] New Materials and Methods From the turn of the century, industrialized building materials inched further and further into the New Orleans cemetery landscape. Most notably, modern cements became more and more available until, after World War II, they were the norm. This meant Portland cement stucco replacing lime. But it also meant the rise of cast concrete, cast stone, and concrete block. A notable example of this was Dognibene Architectural Cast Stone, a company that seems to have dealt primarily with garden features and pottery, but also built tombs. Three Dognibene tombs are known to exist from the 1920s: Two in Hook and Ladder Cemetery (Gretna), and one in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Today, New Orleans bricks are more important to cemetery preservation than ever. Most historic tombs, especially those in need of repair or attention, require brick replacement, a difficult task in a world where traditional brickmaking is all but phased out. The desire for historic brick to be used in walls, paving, and historic buildings also put tombs at risk of brick theft, an incident that is all too common. Even more material is lost to unsympathetic repairs applied to soft brick which can constrict materials and cause cracking, breaking, or even structural failure.

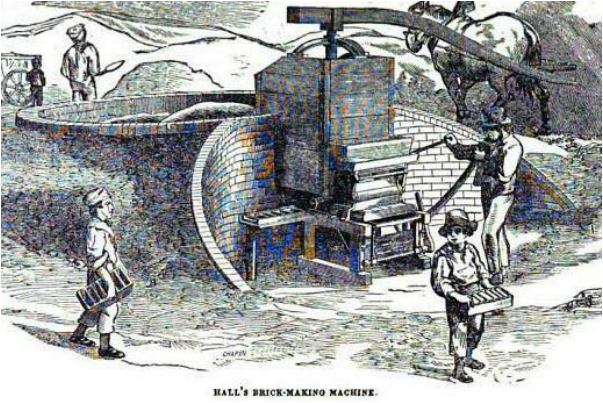

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC only uses historically-appropriate brick for repairs. Where brick must be replaced, brick of similar density and dimension is chosen – we do not salvage bricks from other cemeteries or tombs. You never know who will come back to care for their historic burial place. [1] American Engineer, Vol. 16 (July 1888), 13. [2] “Tammany Steam Brick Yard,” Times Picayune, December 24, 1871, 15; “Lake Brick for Sale,” St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. [3] “History of St. Joe Brick Works,” http://www.stjoebrickworks.com/history.html; Dave Macnamara, “Heart of Louisiana: St. Joe Brick Works,” Fox 8 Live, January 11, 2013, http://www.fox8live.com/story/19517618/heart-of-louisiana-st-joe-brickworks. Part Two of Three The Little Red Row-house in the Cemetery By the 1830s, brickmaking processes were slowly industrializing in the Northeast and along the Eastern Seaboard. The introduction of hand-operated pressing machines led to the production of bricks with smoother edges. Other developments that tempered and cut clay using wires also arose. While these processes would eventually be introduced to New Orleans brickmakers, the clean, dense, fine-edged bricks they produced would be especially associated with northern cities like Philadelphia. In the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the “Protestant Section” is dominated by below-ground burials, a feature attributed to the cultural inclination of non-Catholics toward in-ground burial regardless of circumstances. Those burials which are accommodated by above-ground tombs are distinguished by construction using bricks that would sooner be at home in a northern row-house than a New Orleans tomb. The tombs of the Layton and Johnson families exhibit this brick for tomb construction. The tradition expanded beyond the 1830s, as exhibited by the multiple pressed red-brick tombs associated with Northern-born families in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Unlike traditional New Orleans tombs, these bricks were likely meant to be bare, without stucco. Brick Making Machines and Labor Beginning in the 1840s and likely earlier, brickmaking machines of all different types arose in New Orleans. The first machines were modifications of the “pug mill,” an apparatus by which brickmaking clay is churned and cured in order to make it suitable for molding. In 1848, John Hoey prominently advertised the construction of Hall’s “patent brickmaking machine” on his property near Bayou St. John.[1] This machine was essentially a pug mill in which clay was churned, cured, and extruded into molds. A number of additional brickyards developed along the Carondelet Canal, which ran from Bayou St. John past St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, terminating at Basin Street. Into the 1920s, “Carondelet Walk” featured a great deal of the city’s brick yards, from which bricks could be milled, fired, and transported for sale. Other brick yards thrived along the Mississippi River at Tchoupitoulas Street. In the Riverbend area, a brickyard operated a version of a Hoffman Kiln, another patented machine by which bricks were fired in a rotating sequence. By the 1850s, a number of steam-powered brick-making operations existed along the Gulf Coast in Biloxi, Mobile, and Thibodeaux, which supplied New Orleans markets.[1]

Prior to 1865, most of these operations, as well as smaller brick-making industries on plantation land, were operated by enslaved African Americans who were skilled in trade. In one instance, Gabriel Parker of St. Tammany Parish came to own his own brickyard after emancipation. In many other instances, freed tradesmen passed on their skills to their children.[2] [1] “Biloxi Fire Brick,” Daily Crescent, July 29, 1850, 3; Daily Picayune, June 3, 1866, 3; “Hoffman’s Brick Making Kiln,” Daily Picayune, March 8, 1867, 2; The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans Daily Picayune: 1903), 41; “Brickmaking Machine,” Thibodaux Minerva, January 21, 1854, 3. [2] Ellis, St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac, 159; Crary, J.W., Sixty Years a Brickmaker: A Practical Treatise on Brickmaking and Burning and the Management and Use of Different Kinds of Clays and Kilns for Burning Brick (Indianapolis: T.A. Randall & Co., 1890), 36. Part One of Three “Reds” and “Tans” –hand-molded, wire-cut and pressed: Much can be learned from the bricks that comprise any one tomb. Brick identification can teach us about the construction date of the tomb, later alterations, quality of original construction, and cultural connections of the interred. It can help us understand the process of development in a cemetery, demolition and rebuilding, and where repairs were made. The history of New Orleans brick is as complex as its rich industrial and commercial history. However, the general narrative history of New Orleans brick is simple: “soft reds” were made from the clay of the Mississippi River, otherwise known as “batture,” and “hard tans” were made from the clays found around Lake Pontchartrain.[1] While this narrative is generally true, it belies the greater complexity of masonry in the Crescent City, in which new technologies and new commercial infrastructure compounded available brick types and styles. New Orleans River Brick New Orleans “soft reds” were likely the first masonry units manufactured in the city in the eighteenth century. Using the most basic and common of methods, brickmakers would mine batture from the river’s bank, allow it to dry, temper it, mold it, and fire it. Brick firing prior to the industrial revolution was almost exclusively accomplished without special equipment. Clay was molded in wooden molds, allowed to dry or cure, and then fired. These bricks can be bright or dull red, with soft edges. New Orleans “soft red” or “river brick” continued to be made through the nineteenth century. When we see red river brick in New Orleans cemeteries, their presence alone does not suggest early nineteenth century construction. However, soft reds are much more common in the oldest cemeteries in the city: St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, and to a lesser extent Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. We see them in single-vault step tombs, wall vaults, and other elements of cemetery landscapes that represent the earliest phases of construction. It should be mentioned here that, generally speaking, we should seldom see bricks at all. New Orleans reds are so soft that exposure to the humid elements and temperature cycles of our local climate can cause them to deteriorate. Historic craftsmen were aware of this and typically coated tombs with lime-based stucco, which protected the brick beneath. Stucco coating was also applied to hide the appearance of bricks which were irregular in size and edges and were not considered aesthetically pleasing.[2] “Lake” or St. Tammany Brick

New Orleans “tans,” historically referred to as “lake brick,” were similarly manufactured during the first half of the nineteenth century. Instead of river batture, they were created from clay sourced north and east of New Orleans. Typically, this meant deposits near Lake Pontchartrain, but a number of other sources in St. Tammany parish were also used.[1] The mineral content of St. Tammany clays produced a tan-colored brick, typically with dark inclusions of iron, bauxite, and other impurities. Such bricks were significantly more durable than river bricks.[2] While lake bricks became the standard for a great deal of city construction by the 1850s, there were no requirements for the construction of tombs. Alternately, city ordinance did require that all tombs be “plastered” with protective stucco, which meant that cheaper bricks could be utilized. For this reason it is not surprising that river bricks remained the norm in tomb construction until around the time of the Civil War. Hand-molded lake and river bricks were easily manufactured and acquired locally. Yet the hub of trade and growth that was nineteenth century New Orleans invited a great deal more in the way of building materials and masonry units. Furthermore, cemetery construction typically represents the aesthetic and construction tradition of the memorialized individual or individuals. The best example of this trend can be seen in the Protestant and other Northern-extracted cemeteries of the city.[3] [1] Ellis, Frederick S., St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1981, 108. [2] “An Ordinance to Establish a Ferry near the St. Mary’s Market, and Connected with the City of Lafayette,” True American, November 20, 1838, 1. [3] “Building Material, Bricks, Firewood,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, August 02, 1859, 4. Advertising brick from France, England, and America. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly