|

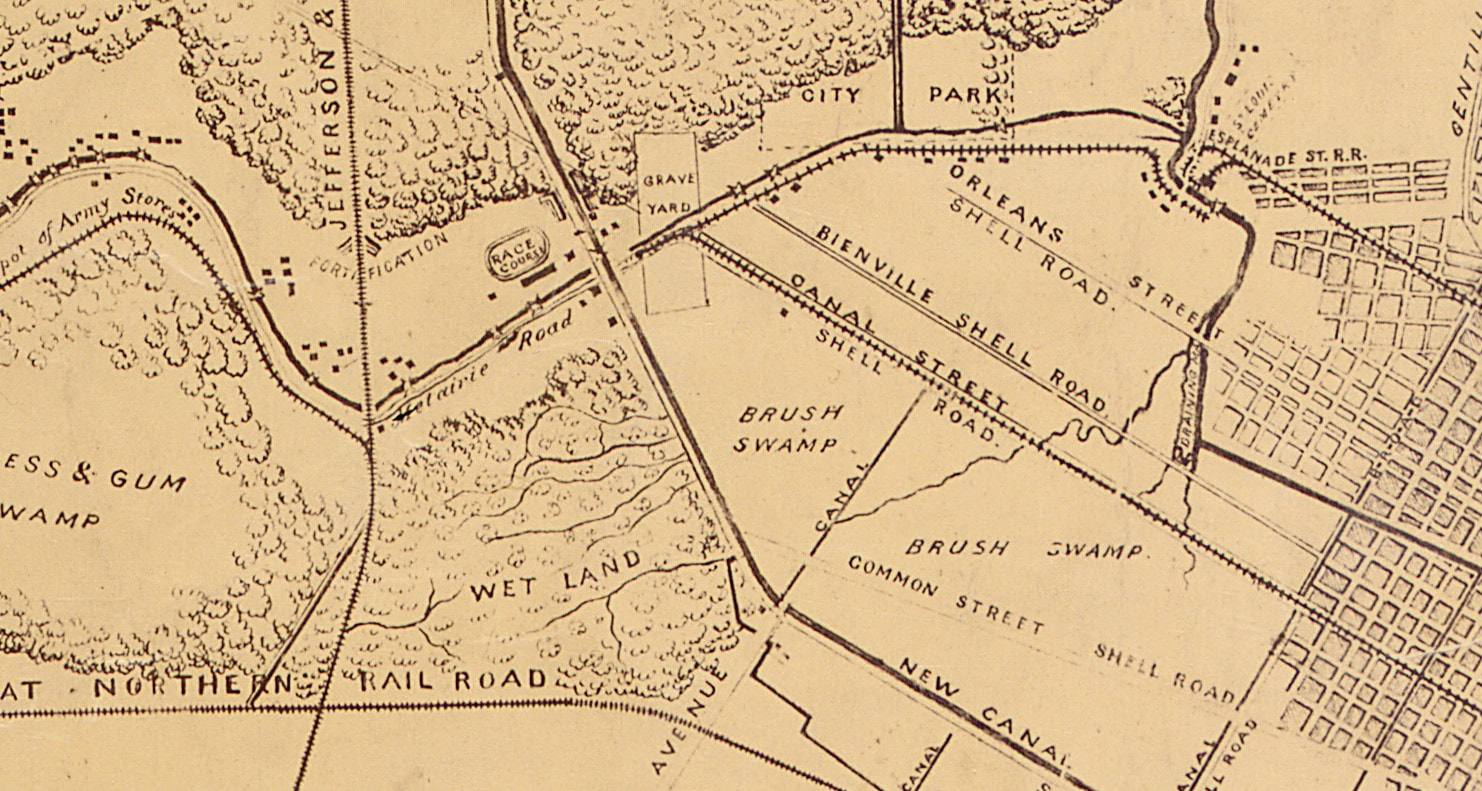

This is Part Two in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here. 1841: St. Patrick’s Cemetery At the same time that Americans from the northeast were moving en masse to New Orleans, a separate wave of immigration from Ireland made a great impact on the city. Immigrants fleeing famine and political unrest in Ireland came to New Orleans and settled mostly in what is now the Faubourg St. Mary neighborhood of New Orleans, abutting the Central Business District and what is now the Crescent City Connection bridge. These immigrants formed what is now Irish Channel, although the boundaries of this neighborhood have changed over time.[1] The neighborhood formed from settlement patterns dependent on the construction of the New Basin Canal. In 1833, the Parish of St. Patrick was founded to accommodate Irish Catholics in the neighborhood. By 1840, St. Patrick’s Church was constructed on Camp Street.

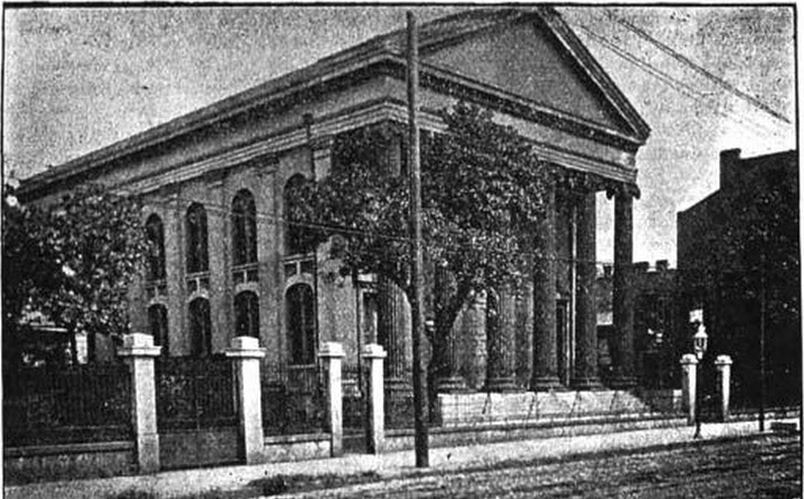

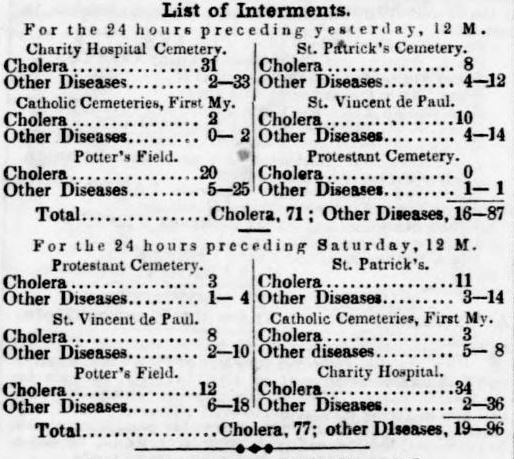

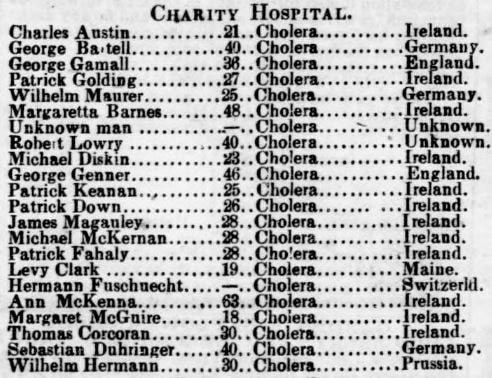

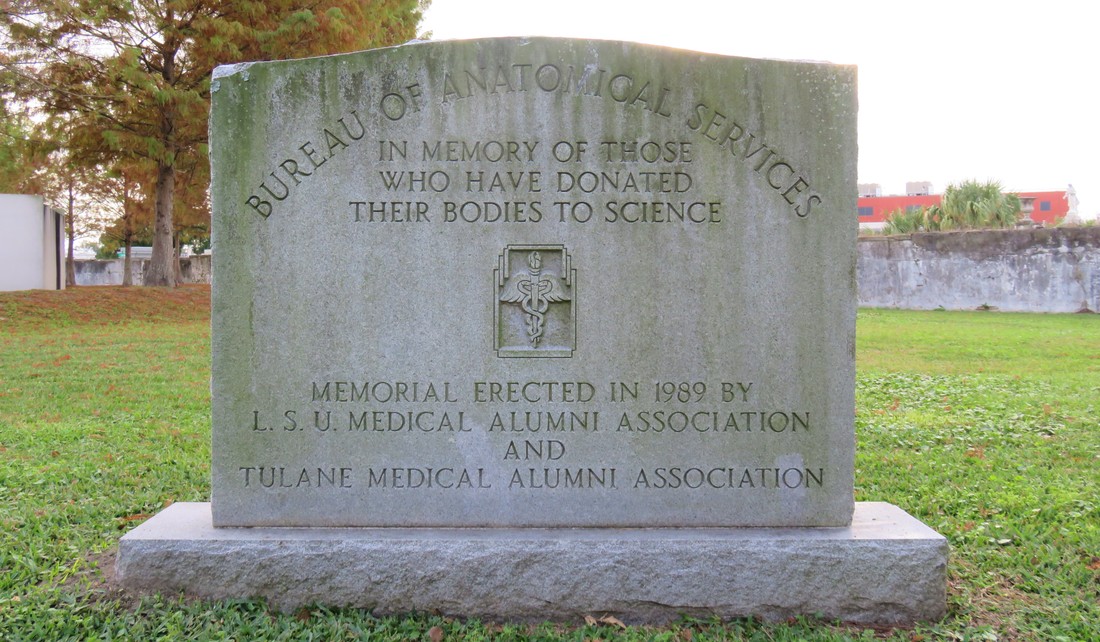

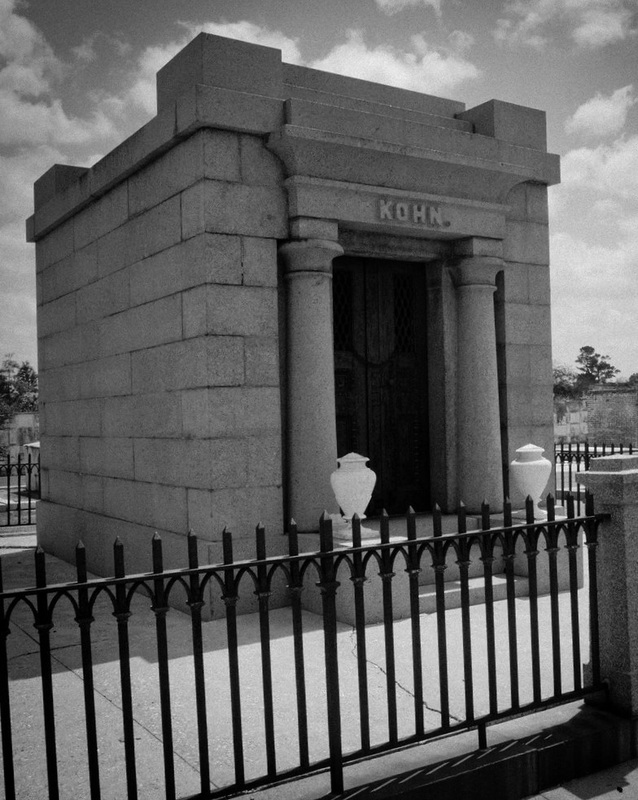

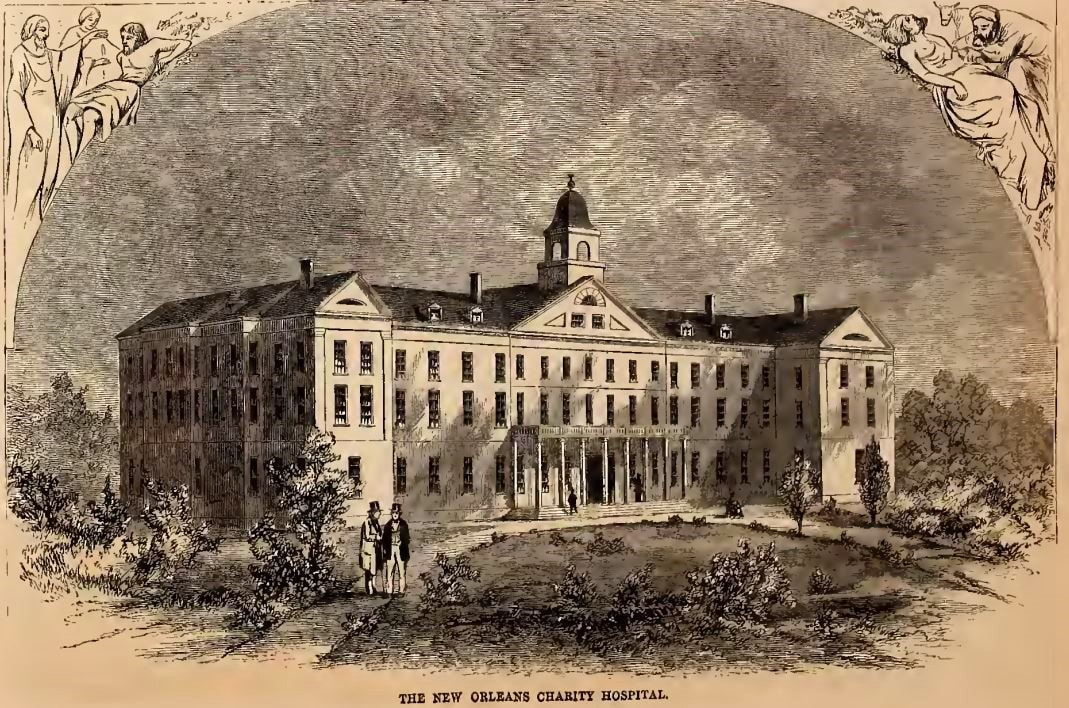

The St. Patrick Cemeteries, so fresh and clean in their snow-white garb and pebbly walks, always attract attention. Here lie the sturdy Irish pioneers who came to New Orleans in the early part of the last century and helped to make her history the proud tale it is… they breathe throughout the spirit of the Catholic faith. Special attention is directed to the beautiful Calvary shrine at the further end of St. Patrick’s No. 1 and the Mater Dolorosa that marks the entrance to St. Patrick’s No. 2.[3] The Calvary statue was designed by then-prominent monument man Charles A. Orleans, consisting of “a wooden cross twenty feet high with life-sized statues of the crucified Christ, Mary Mother of Jesus, His beloved disciple John, and Mary Magdelene. The statues were cast in Paris.”[4] In 1973, in the midst of trends toward community mausoleums, the Calvary was removed to make way for the Calvary Mausoleum. 1846: Dispersed of Judah Cemetery Along with Americans and Irish immigrants to New Orleans, another group of established immigrants and newcomers found their burial place at the end of Canal Street. Jewish people had long lived in New Orleans in small communities, first of primarily Sephardic Jews (of the Spanish-Portuguese tradition) from the Caribbean and England, then later Ashkenazi Jews from Germany and Alsace-Lorraine. These communities first organized in 1828 to found Gates of Mercy congregation, which had a synagogue on Rampart Street near St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Gates of Mercy was an Ashkenazi congregation, and Sephardic Jews in New Orleans sought their own place of worship. This hope was fulfilled in 1846 when organizer Gershom Kursheedt helped aging benefactor Judah Touro found congregation Nefuzoth Yehudah (Dispersed of Judah) in 1846. Dispersed of Judah, a Sephardic congregation, was one of many religious organizations to benefit from Judah Touro’s generous will, which also founded Touro Infirmary, later to become Touro Hospital. In 1881, Dispersed of Judah and Gates of Mercy congregations would merge. The new congregation was eventually renamed Touro Synagogue. In the same year Dispersed of Judah congregation was founded, property adjoining St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2 along Canal Street was purchased for a cemetery. Dispersed of Judah was the second Jewish cemetery in New Orleans. Gates of Mercy had established a cemetery on Jackson Avenue near Saratoga Street in 1828, but this cemetery was demolished in 1957, part of a trend that will be discussed in a later part of this series. Thus, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery is the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. Members of Dispersed of Judah congregation were often tied to English colonial or business interests, arriving in New Orleans from the English-colonized Caribbean or New York. This Anglo-cultural tie, as well as a religious need to bury belowground, allowed Dispersed of Judah to grow into a small version of a northern cemetery. The landscape today retains some elements of this – box tombs and obelisks, trees, and raised monuments. The cemetery is probably best known for the marble monument of Lilla Benjamin Wolf (died 1911), carved into the shape of an empty chair with foot stool. A local story tells the sale of Mrs. Wolf sitting in her chair in life, outside her family’s shop, calling potential customers inside. This may have been a deeply personal choice of monument for the Wolf family, although “the empty chair” was also a common funerary symbol at the turn of the century. 1848: Charity Hospital Cemetery By 1848, Charity Hospital was an institution nearly as old as New Orleans itself. Founded in 1732, the hospital provided care to all patients without regard to race, nationality, religion, or sex. Throughout the nineteenth century, Charity Hospital cared for thousands of newly-arrived immigrants who fell ill after the trans-Atlantic journey, or who were especially susceptible to New Orleans epidemics of yellow fever and cholera.[5]  Charity Hospital's fifth building, in use from 1832 to 1939. Located on Common Street between St. Mary and Girod Streets, it was replaced in the 1930s by "Big Charity," a building designed by Weiss, Dreyfus, and Seiferth, who also designed the Louisiana State Capitol at Baton Rouge. Image from Harper's Weekly, September 3, 1859, via archive.org.

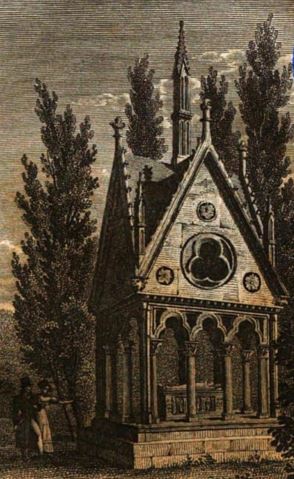

The firemen used axes to demolish the fence to save the [adjoining] St. Patrick’s Cemetery property, but nothing could be done to prevent destruction, and, after the flames had consumed the grass, covered the graves under smoldering ashes, with no crosses or headboards to identify the original plots, nothing was left for the friends or relatives of the dead to distinguish one grave from the other.[7]  Charity Hospital Cemetery in 2003, looking over the fence from St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2 and toward Canal Street. The flags present on the site suggest that it may have recently been mapped using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to identify gravesites. Photo by Dale Boudreaux, via usgenwebarchive.com Charity Hospital Cemetery would receive scores of burials each day during successive yellow fever and cholera epidemics. Later, the cemetery would also receive the bodies of those who had donated their remains in death as medical school cadavers. After Hurricane Katrina, the cemetery would be revised into a new kind of memorial. 1849: Odd Fellows Rest Charity Hospital was the third cemetery to be established at the end of Canal Street. By that time, the land was still overwhelmingly rural, with few structures save the Halfway House and Toll House along the Shell Road, and the towering Egyptian pillars of Cypress Grove. But around the same time Charity Hospital Cemetery was established, another great landmark was in the works. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), a fraternal organization established in England in the 1700s, had founded a local lodge in New Orleans in 1833. The origins of IOOF’s name seem debated; one explanation has been that the “Odd” designation came from the society’s openness to all members despite trade or occupation. The official IOOF website tells a different story: “…it was odd to find people organized for the purpose of giving aid to those in need.” Indeed, the IOOF’s stated purpose is “Visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead and educate the orphan.” The Odd Fellows were also known as the “Three Link Fraternity,” a reference to their motto “Friendship, Love, and Truth,” often symbolized by the three-link chain. By 1858, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana had more than twenty subordinate local lodges, including the Crescent, Teutonia, Howard, Magnolia, Covenant, and Polar Star Lodges, all beneath the IOOF Grand Lodge umbrella. In addition to establishing widows’ and orphans’ assistance, and constructing one, and then another imposing Odd Fellows Hall building, the local Odd Fellows sought to establish their own cemetery by the late 1840s. Odd Fellows cemeteries were a national phenomenon in the nineteenth century, and can still be found in places as disparate as New Jersey, Texas, Nebraska, California, and Oregon. New Orleans Odd Fellows sought to do the same. Previous to this time, the land acquired by respective cemetery owners like St. Patrick’s Church, Charity Hospital, and the Firemen had been allotted using lines of property demarcation corresponded to Lake Pontchartrain and not the Mississippi River, leading to the long lots exemplified best by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1, 2, and 3. These property lines ran across Bayou Metairie at angles, leaving a small triangle of land wedged between St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Bayou Metairie, and Canal Street. In 1848, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana IOOF purchased this small triangle of land for use as their cemetery – the first, but not the last fraternal cemetery at the end of Canal Street.[8] On February 26, 1849, the various Odd Fellows Lodges converged on the Place d’Armes (Jackson Square) to form an “exceedingly beautiful” procession to celebrate the consecration of Odd Fellows Rest.[1] The parade of hundreds was decked in black crape, banners, and emblems of the many symbols recognized by the Odd Fellows. They marched through the French Quarter in a serpentine route, up one street and down another, across Canal Street and through the American Sector (now the Central Business District) where they converged at the New Basin Canal and boarded carriages to proceed up the New Shell Road to the Halfway House.[2] At the Halfway House, the Odd Fellows re-formed their procession, following a carriage drawn by six gray horses and carrying a sarcophagus containing the remains of sixteen Odd Fellows, exhumed from other cemeteries to be re-interred at Odd Fellows Rest. The procession entered through the cemetery’s gate, a granite Egyptian Revival post-and-lintel that mirrored in style if not size the grand entrance of Cypress Grove immediately across Canal Street. Once inside, the parade ended at the center of the cemetery, where a tomb had been prepared. Poems were read and oratories recited, and the remains reburied. The entrance to Odd Fellows Rest would remain at the center of its Canal Street boundary for more than fifty years. The granite entryway was enclosed by two cast-iron gates produced in Spain for the Odd Fellows that portrayed dozens of the Order’s symbols: cornucopia, beehives, globes, books, shepherd’s staffs, stars, axes, and a mother protecting four children. The gates were surmounted by finals depicting the sun and moon, and atop all of this was the perennial Odd Fellows Symbol, the heart-in-hand. In the mid-twentieth century, New Orleans photographer Clarence John Laughlin would capture the gates in their historic context, complete with detail and careful multichromatic paints. By the 1970s, much of the original ironwork had been stolen or lost. Within the walls of Odd Fellows Rest, the cemetery would be populated by hundreds of enclosed wall vaults, belowground burials, high-style tombs, and even a tumulus. In the 1850s, local sculptor and stonecutter Anthony Barret (1803 – 1873) constructed a 48-vault society tomb for the Teutonia Lodge of the Grand Order IOOF. The society tomb, later transferred to Southwestern Lodge No. 42, was designed reminiscent of an Italian loggia, with each arched group of vaults framed by inverted torches carved in marble. The Teutonia Lodge tomb was surmounted by marble urns on each corner of its roof. At the primary façade of the tomb was the piece-de-resistance of the structure: a remarkably ornate marble panel carved with dozens of symbols of the Order, each framed with fine scrollwork carved in relief. At the center of the panel, the protecting mother sits nursing a baby and wrapping her cloak around another child. Anthony Barret was well known for his remarkable stonework, carving some of the finest relief sculptures found in the Lafayette Cemeteries and elsewhere. Even still, the Teutonia Lodge tomb is the greatest artistic accomplishment of Barret’s to survive into the present day. [1] Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma, 172.

[2] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 132-133, 139-140. [3] The New Orleans Picayune, The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: The Picayune, 1904), 152. [4] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 33. [5] John E. Salvaggio, New Orleans’ Charity Hospital: A Story of Physicians, Politics, and Poverty (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1992), 35-45. [6] “Second Municipality Council,” Daily Picayune, May 19, 1847, 2. [7] “A Cemetery Blaze: Flames Sweep the Spot where Charity Hospital Dead are Interred,” Times-Picayune, February 27, 1905, 11. [8] An 1833 map of New Orleans from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain shows the intersection of Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal divided into properties belonging to the New Orleans Banking and Canal Company, and illustrates how the property lines correspond with Lake-oriented parcels. A high-resolution of that map is available here. [9] “Consecration of Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, February 27, 1849, 1. [10] Ibid.

1 Comment

As any narrative on de Pouilly does, this article relies on the groundbreaking research and thesis of Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University thesis, 1992. Which exquisitely analyzed de Pouilly’s work in New Orleans cemeteries. One hundred and forty years ago, on February 21, 1875, Jacques Nicholas Bussiere de Pouilly died in his home on St. Ann Street. In his seventy years of life, de Pouilly had been the harbinger of European neoclassical and revival architecture in New Orleans. We see his touch on our city streets – in St. Augustine Catholic Church, and most notably St. Louis Cathedral. But his influence was arguably greatest in the city’s cemeteries. De Pouilly’s work is present in nearly every viewpoint of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, and much of Cypress Grove Cemetery. The breadth and innovation of his tomb architecture generated uncountable replications and inspirations, the products of which have shaped our burial grounds. J.N.B. de Pouilly was born in July 1804 in Châtel-Censoir, France, southeast of Paris. While much of his early life is unclear, it is assumed that in his architectural training he was influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, if not a student of the school himself.[1] He arrived in New Orleans in 1833, a time in which the French-speaking population of the city hungered for reconnection with Continental styles. He quickly became the architect of note for the city’s First District, designing the St. Louis Exchange Hotel, among many other residential, commercial, and religious projects.

While Père Lachaise and Creole cemeteries like St. Louis may appear stylistically similar, de Pouilly had the significant task of fundamentally shifting the function of his New Orleans tombs from their Parisian prototype. Although the monuments of Père Lachaise appear to be tombs or mausoleums, their design accommodates instead for below-ground burial. That the architect’s designs kept their Parisian aesthetic while having been fundamentally re-worked to allow for above-ground burial is among the more impressive of his professional achievements.[3]

In addition to the French St. Louis Cemeteries, de Pouilly worked also in American-dominated Cypress Grove Cemetery (est. 1840). In Cypress Grove, de Pouilly additionally contracted with granite magnate Newton Richards to build the memorial of fallen firefighter Irad Ferry (died 1837). He relied, too, on Monsseaux and Foy to construct such masterpieces as the Maunsel White tomb. De Pouilly clearly had a strong grasp on the value of trade and materials, based on his choice of craftsmen and his apparent innovations in the world of cast stone. De Pouilly’s career was marred by two construction disasters in the 1850s – first, the collapse of the central tower of St. Louis Cathedral while de Poilly was head architect, and second the collapse of a balcony at the Orleans Theatre. From this point onward, his rising star waned, but it appears never to have faded in New Orleans cemeteries. In 1874, de Pouilly composed the final drawing in his only surviving sketchbook – a tomb he designed for himself and his family. This tomb, like many depicted in his prolific sketches, would never be constructed. Instead, de Pouilly was interred in a family wall vault in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Although the location was surely not intentional, the wall provides a lovely view of a number of de Pouilly-designed tombs. In a nearly-illegible detail to his memorial tablet, the signature of Florville Foy can be detected as the carving hand of de Pouilly's final tablet. De Pouilly’s obituary on February 22nd spoke grandly of a man who lived honestly and in service of his profession:

St. Peter’s lofty dome cenotaphs the name of Michael Angelo [sic]: Sir Christopher Wren’s greatness is sepulchred in the mightiness of St. Paul’s. Mr. De Pouilly fashioned no wonders such as these, but yet a greater, the enduring fabric of an honest life, and will be entombed in the constant remembrance of devoted friends. After a painful and lingering illness, Mr. De Pouilly, hoary with the winters of seventy years, and surrounded by children and other relatives, bade farewell to things of earth. This sad event occurred yesterday, Sunday, 21st.[4] The Daily Picayune made no note of the many cenotaphs de Pouilly himself had helped write, in the tablets and along the aisles of our cemeteries. But if 140 years is a sufficient measure of the timelessness and impact of one’s work, his name certainly engraved upon many more memorials than just his own. Below is a gallery of only a portion of de Pouilly’s work, and a few tombs inspired by his designs. Photos by Emily Ford unless otherwise noted. [1] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” 5-7.

[2] Peggy McDowell and Richard E. Meyer, The Revival Styles in American Mortuary Art (Popular Press, 1994), 59. [3] Masson, 30-35. [4] “In Memoriam – J.N. de Pouilly,” Daily Picayune, February 22, 1875, 2. At the end of the main aisle in Square 1 of St. Louis No. 2 is a simple tomb with a low-pitched gable roof. Coated in modern cement and latex paint, it is difficult to determine much about its original appearance. Perhaps it was once coated in brightly-colored stucco, or its roof tiled in slate or terra cotta. Ironwork may once have enclosed its simple design. Without the fortunate discovery of an historic photograph, which is extremely rare, the elegant past of this tomb may never be known. But the de Armas tomb offers a hint to the scrutinizing eye. Its marble closure tablet is embellished with an ornate relief carving depicting a winged hourglass encircled with a floral wreath. The hourglass is surrounded by a snake eating its tail – the ouroboros – a symbol of immortality. Among the few depictions of the winged hourglass in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, this carving is by far the most detailed. Such a carving is indicative of a level of style and craftsmanship long faded from New Orleans cemeteries. At one time it was not alone in its ornamental beauty, but instead belonged to a rich landscape of beaded wreaths, draped urns, and weeping angels. Even today, the de Armas tomb is not alone in one regard. Nearly three miles away, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2’s younger sister, St. Louis No. 3, stretches along the edge of Bayou St. John in long aisles. Amidst its large lots and photogenic tombs is the tomb of the Depaquier family. Uncompromised by modern repairs, the faded stucco walls bely that the tomb was once limewashed a dark rose color. The pitch of its roof is reminiscent of the de Armas tomb. The closure tablet of Dupaquier tomb is bordered with a carved braided rope. Atop its simply-lettered epitaph is a winged hourglass nearly identical to that found on the de Armas tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Studies of cemetery craftsmanship in New Orleans have shown that few motifs, materials, or methods in cemetery stonecarving are the result of happenstance. Who carved these tablets? What do they symbolize? And why did the Dupaquier and de Armas families end up owning identical tablets? The de Armas and Dupaquier Families The two tombs are the burial places of the patriarchs of their respective families. In St. Louis No. 2, Michel Theodore de Armas (sometimes listed in documents as Michael or Miguel), was a notary and lawyer who was born in New Orleans in 1783 and died in 1823.[1] In St. Louis No. 3, Claude Dupaquier was born in France in 1806, arrived in New Orleans in the 1840s, and died in 1856.[2] Between 1823 and 1856, life expectancy was around 37 years, so that these men died at age 40 and 50 (respectively) is unremarkable. Both de Armas and Dupaquier had children that became important members of New Orleans’ business and social circles after the Civil War. Dr. Auguste Dupaquier, who is buried with his parents, was described as having a “gentle, loving, and kindly temperament, mixed with firmness and rare energy, and he secured the affections of all whom he approached.[3]” Dr. Dupaquier had no discernable interaction with the children of de Armas, and it is unlikely that the families had enough relation to construct matching tombs knowingly. One significant similarity between the Michel de Armas and Claude Dupaqueir was their preference for the French language. Both tablets are carved in French.

In nineteenth century New Orleans, a person’s linguistic and cultural identity often determined who they chose to carve their final epitaph or build their eternal resting place. For de Armas, or his widow, Gertrude St. Cyr Debreuil, it would have been a given that they chose Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. New Orleans cemeteries are populated with the small, often overlooked signatures of local stonecutters. Often these signatures wear away, and craftsmen often neglected to sign their work at all. Many stonecutters began their careers working for other more established cutters, signing the name of their master instead of that of the apprentice. These realities complicate the study of cemetery craftwork. In the case of the de Armas closure tablet, a small, clean-lettered signature is present at its bottom right-hand corner – MONSSEAUX. The Depaquier tomb retains no signature at all. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux Like Claude Depaquier, Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux (1809-1874) was a French native who arrived in New Orleans as an adult.[4] Present in New Orleans by 1842, Monsseaux is best known as the stonecutter who built many tombs designed by architect J.N.B. De Pouilly. These included many famous tombs in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Monsseaux often worked with other stonecutters in either a master/apprentice role or as business partners. In addition to his work for J.N.B. de Pouilly, his signature is often found beside other cutters like Tronchard and Kursheedt & Bienvenu. Through his entire career, Monsseaux held the same marble yard on St. Louis Street at the corner of Robertson Street – directly beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 and New Basin Canal. Through his career, Monsseaux also sold marble to fellow stonecutters; he partnered with others to secure equipment and technology that advanced the trade. Most notably, he owned a steam marble works for some time in the 1870s, the rights to which he lent to other cutters Stroud and Richards.[5] Monsseaux’s accomplishments were many, but his clientele was rather distinct. Most of Monsseaux’s signed tablets are carved in French. In this manner, Monsseaux is a French counterpart for German-speaking stonecutters of the time who served a distinctly German clientele. There are always exceptions – Monsseaux built the DePouilly-designed Iberian Society tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Yet the majority of his work served French-speaking clients who belonged to the upper echelons of New Orleans society. Stylistic Inspirations and Symbolism French speaking upper-class New Orleaneans in the 1830s were enthralled with the style and beauty of tombs found in Paris’ Pere Lachaise Cemetery at the time, and Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux gladly catered to that demand. Sarcophagus-style tombs with corner acroteria and inverted torches appeared in St. Louis No. 2 during this time. These tastes adapted through the 1850s and into the first years of St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. Greek Revival temples and Egyptian Revival tombs rose in the squares of the both cemeteries, mimicking the aisles of the great French burial ground. Often, it was Monsseaux who provided his clients with these romantic sepulchers. Pere Lachaise Cemetery is populated with hundreds of winged hourglasses. In fact, the first image to greet the visitor at the cemetery gate is a pair of such hourglasses. This is also the case at Montparnasse Cemetery, also in Paris. The history of the winged hourglass as a funerary symbol appears to split along linguistic and cultural lines in the United States. In the English-speaking Northeast, it is contemporary with the skull-and-crossbones and death’s head, symbolizing the fleetingness of time. In this context, the winged hourglass was contemporary to the 18th century and faded from popularity by the 1830s. French-speaking New Orleans funerary culture developed more closely to that of Paris than its American cousins, however. The winged hourglass is seldom seen in tombs constructed prior to 1820. It does, however, appear to grow in popularity from 1820 through the 1850s, when the de Armas and Dupaquier tombs were constructed. This inspiration was drawn directly from the Parisian cemeteries. And New Orleans was not alone in this inspiration. Not to be outdone as a European city in the New World, Buenos Aires’ Recoleta Cemetery, founded in 1822, hums with the flutter of winged hourglasses. The de Armas and Dupaquier families may never have known each other, but they are together twin scions of a lost cemetery landscape. Opulent with their floral wreaths and outspread wings, their hourglass tablets were likely carved by Monsseaux himself or an apprentice. It is possible, even, that the Dupaquier tablet was a replica of de Armas’, carved by a student still learning his trade. Or, perhaps, both designs were borrowed from a pattern book imported from Paris. In any case, they endure as silent reminders of the importance of each tomb in the larger landscape of our historic cemeteries. [1] Florence M. Jumonville, Ph.D., ‘Formerly the Property of a Lawyer’: Books that Shaped Louisiana Law. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Library Facility Publications, 2009, 7.

[2] Orleans Death Indices 1804-1876. Vol. 17, 312. [3] “Death of Dr. Dupaquier,” New Orleans Daily Democrat, April 8, 1879, p. 8. [4] Charles LeJ. Mackie, “Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux: Marble Dealer,” printed in SOCGram, Fall 1984, 14-16. [5] Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly