|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC maintains an informal database of cemetery vandalism incidents around the world based on news reports. From online journalistic alerts, each report of a vandalism incident is cataloged for location, motivation (if one is identified), number of markers affected, estimated repair costs (if identified) and other factors. The data below is based on this database, cataloged from January to December 2017. It must be noted that cemetery vandalism is often unreported to local press. Our database cannot include unreported vandalism and does not represent the most comprehensive total of vandalism incidents. Instead, it provides a snapshot of some incidents and issues. In 2017, 105 individual incidents of cemetery vandalism were reported to local press across the United States. While the tally of individual incidents, ranging from New York to Hawaii, Florida to Oregon, is significantly less than those reported in 2016 (184 incidents) the total number of headstones and markers affected increased from 1,811 to 2,353, and estimated repair costs reported by cemetery authorities increased from approximately $488,000 in 2016 to approximately $1,766,000 in 2017. Cemetery vandalism is a much more common occurrence than it is commonly understood to be. Each year, hundreds of cemeteries experience loss and damage resulting from stolen grave goods, toppled stones, and graffitied markers. As we noted in our 2016 post on cemetery vandalism, the motivations for such acts vary widely. In many cases, acts of vandalism can be explained by adolescent antisocial behavior – “kids” knocking over headstones for fun or as an expression of control. But in so many other cases, vandalism has a deeper motivation as an expression of political or racial undercurrents. In 2017, racial, religious, and politically motivated cemetery vandalism was pushed to the forefront of American news coverage. In our recap of 2017 in cemetery vandalism, we review incidents of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents, and the community response that helped cemeteries recover. After August protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, incidents of cemetery vandalism targeting Confederate monuments increased. From this point, we will also discuss cemetery vandalism incidents outside the United States with an eye to similarities of motivation. Yet despite 2017’s increases in cemetery vandalism severity, responses from law enforcement may have increased in efficacy. A number of vandals who perpetrated cemetery crimes in 2016 were identified and apprehended this year, and responses have grown more robust. Anti-Semitic Cemetery Vandalism In February 2017, two Jewish cemetery vandalism incidents became national news. Outside St. Louis, Missouri, approximately 175 headstones at the Chesed Shel Emeth Society Cemetery were toppled. Within a week, 100 headstones at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania were also toppled. Vandalism incidents in which more than one hundred headstones are affected are not entirely unusual. However, the two incidents in Philadelphia and St. Louis occurred concurrently with popular malaise around the specter of anti-Semitism – dozens of false bomb threats were made by phone to Jewish community centers around the country in the previous month. When these two cemeteries were vandalized, national and local response was enormous. While the perpetrators in either incident have yet to be apprehended, and the St. Louis incident was not initially pursued as a hate crime, these two cemeteries became rallying points for resistance to anti-Semitism. The incidents also turned the public eye to the larger issue of cemetery vandalism in such a way that affected future responses to such incidents. Unfortunately, these two large-scale incidents were not the only examples of anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism to occur in the United States in 2017. In January, two young women and a young man (ages 19, 16, and 20 years old, respectively) were arrested for anti-Semitic graffiti at a cemetery in Scottsburg, Indiana. Also in January, anti-Semitic and anti-police graffiti was found at Oak Grove Cemetery in Hyannis, Massachusetts – an incident that was investigated as a hate crime. Additional incidents in Rochester, New York, and Melrose, Massachusetts in March and July (respectively) were so investigated. In May, another cemetery in Philadelphia was the victim of what police investigated as an anti-Semitic hate crime.

In fact, money raised to aid Mount Carmel and Chesed Shel Emeth exceeded their needs. Some money raised in Missouri was sent to other St. Louis-area cemeteries to help improve security. Other excess funds were earmarked for other Jewish cemeteries, including Golden Hill Cemetery in Lakewood, Colorado. The state legislatures of New York and Pennsylvania discussed raising criminal penalties against those convicted of cemetery vandalism. While New York did see a threefold rise in cemetery vandalism claims to their state cemetery preservation fund, the state declined to increase penalties. In July 2017, the state of Pennsylvania did increase penalties, including a $2,000 fine and possible 30 days imprisonment. Other Religious and Culturally Motivated Vandalism In general, religious and culturally-motivated cemetery vandalism increased from 2016 to 2017. While in 2016 a number of African-American cemeteries were targeted for race-based vandalism, such crimes appeared to target other groups in 2017. In August, newly-established Al Maghfirah Cemetery outside Minneapolis, Minnesota was vandalized with swastikas and menacing spray-painted messages. The Federal Bureau of Investigation was notified and began investigation. Also in August, Cypress Hills Cemetery in Glendale, Queens, New York was vandalized by three young men who spray painted anti-Muslim, anti-Asian, and anti-African American graffiti on cemetery walls. In this case, the perpetrators were filmed by surveillance cameras. The three men were arrested in October 2017 and charged with hate crimes. Confederate Monuments After the mass murder of nine worshippers at Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015, national dialogue turned to the removal of Confederate monuments throughout the country. The Confederate monuments in question were, in almost all instances, those set in public space and not in cemeteries. For example, New Orleans city council voted to remove four public Confederate monuments in December 2015, but excluded Confederate monuments in cemeteries from discussion. In 2017, public discourse regarding Confederate monuments in New Orleans did include cemeteries, but only as possible locations that removed monuments could be relocated. In 2016, only one incident of vandalism targeting Confederate monuments took place, in Raleigh, North Carolina. After the shocking protests and violence that took place at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017, targeted cemetery vandalism increased. Five incidents of vandalism of Confederate monuments took place in United States cemeteries after Charlottesville, as well as one additional incident involving a Union soldier monument in California. In Los Angeles, California, a Confederate monument placed in Hollywood Forever Cemetery by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1925 was graffitied with the word “NO” in permanent marker. Shortly afterward, the UDC removed the monument and placed it in storage. Other cemeteries increased surveillance and security after the Charlottesville protests in anticipation of targeted vandalism. Such was the case in Springfield National Cemetery in Missouri. However, during a shift change between security details, red paint was splashed across a monument to a Confederate major general. This incident was tied in newspaper reports to a recent statement by Missouri state legislator Warren Love, who stated that those who vandalize monuments should be “hung high with a rope,” prompting calls for Love’s resignation. Other incidents took place in Fairfax, Virginia, and Columbus, Ohio, where a zinc monument placed in 1902 was pushed from its pedestal and shattered. Its detached head was stolen. At Woodlawn Cemetery in West Palm Beach, Florida, a 1941 Confederate monument was tagged with multiple messages in red spray paint. Most recently, Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Rome, Georgia, was targeted when a granite statue was pushed from its pedestal and repeatedly struck with an unknown instrument. Catching Vandals: “Who Does Something Like This?” In our 2016 vandalism blog post, we noted that is extremely unlikely for cemetery vandals to be identified and apprehended. In 2017, arrest of cemetery vandals was slightly more likely than in the year previous. Most notably, the investigation into 2016 anti-Semitic vandalism of Beth Shalom Cemetery in Warwick, New York, came to a close in October when a suspect was arrested for the incident. The minor was charged with a hate crime and tampering with physical evidence, after he deleted photographs of the vandalism from his phone. The minor was found to have conspired to commit the vandalism with two other people, one of whom made a meme of the suspect's face under the caption “Secretly spray paints Jewish cemetery and gets away with it.”

The cemetery owners claimed the $15,000 in damage would be covered by the cemetery itself. Moreover, the cemetery held a cookout for families whose property had been damaged, at which they were given new flowers and flags to place on their lots. In September 2017, more than thirty of a total one hundred monuments were toppled in Bohemian Pecenka Cemetery in Marysville, Kansas. The cemetery was cared for by the local high school 4H, whose members overheard their five teenage classmates admitting to the act and turned them in. In October, a Cordova, Alabama man was arrested for vandalizing Mt. Carmel Cemetery. In an interesting attempt at community policing, the vandal, 23 year-old Joshua Hicks, was brought to the cemetery to meet families whose property he’d damaged. Hicks explanation for why he vandalized the cemetery: “… he likes to get intoxicated, gets bored, and likes to vandalize.” Other arrests for cemetery vandalism in 2017 included the June arrest of an adult man who repeatedly vandalized Historic Japanese Cemetery in Oxnard, California. This man was known to the cemetery and was understood to have mental health concerns. The cemetery declined to pursue charges. A 48 year-old man in Kahoka, Missouri was arrested for removing marble closures from a mausoleum. In Schenectady, New York, a 43 year-old man was arrested for scratching his “rapper’s name” into a headstone at Vale Cemetery. International Cemetery Vandalism Oak and Laurel’s cemetery vandalism database includes all cemetery vandalism-related reports written in English. This usually includes the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, where cemetery vandalism is frequently reported. For example, at Berri Cemetery in Riverland, South Australia, three boys aged 9, 10, and 11 were turned in to the cemetery after their mother found out they had been toppling headstones. As in 2016, vandalism in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland continues to be an issue associated with sectarian conflict. In January 2017, a man in his 50s was arrested for vandalizing the monument of Irish politician Éamon de Valera in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. In addition to criminal charges, he was banned from the cemetery. In the April anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, a remembrance wall at Glasnevin was splashed with paint.

Additional incidents took place in Northern Irish cemeteries, including Belfast City Cemetery and Goldenbridge Cemetery, where the front gate was set on fire. Derry/Londonderry City Cemetery, which was noted in 2016 to have repeated vandalism incidents, did not report any incidents in 2017. In December 2017, two tour guides in Belfast began tours of the city’s cemeteries as a means of combatting vandalism. Other international cemetery vandalism events highlight local and regional political strife. In January, cemeteries in Poland and Ukraine were vandalized with Nazi graffiti and anti-Semitic slurs. Both instances were blamed by local press on Ukrainian nationalists. A Jewish cemetery in Lorraine, France, was vandalized in April in an incident that was seen as anti-Semitic. In Lausanne, Switzerland, the Muslim section of a public cemetery was vandalized with graffiti reading “Muslims out of Switzerland.” Responding to Cemetery Vandalism Cemetery vandalism can be seen as a barometer for political and social unrest. In 2016, we looked at this aspect of cemetery vandalism primarily from an international standpoint – examining vandalism in Ireland and Armenia. In 2017, cemetery vandalism reflected such concerns in the United States more than in the years previous. While this increase in targeted cemetery vandalism is very concerning, it must not be overlooked that heightened attention to cemetery vandalism has had an impact. Recovery from vandalism incidents is slightly more often reported and also includes focus on the communities that use and cherish a cemetery. In 2017, some cemeteries even published press releases asking community members to become involved and vigilant before cemetery vandalism occurs. Criminological theory states that cemeteries which appear cared for and visited tend to experience less vandalism. This understanding appears to have been utilized in vandalism responses in 2017. Closed circuit television, security, and other physical and intangible barriers to antisocial activity have also become more common. Prevention and community involvement are shown time and time again to be the best things to combat cemetery vandalism. Cemetery vandalism is inevitable, but can be mitigated and prevented to an extent. As we move forward into 2018, we hope to see the kind of police follow-through, community response, and enthusiastic recovery that was seen in 2017 despite the discouraging events that precipitated them.

5 Comments

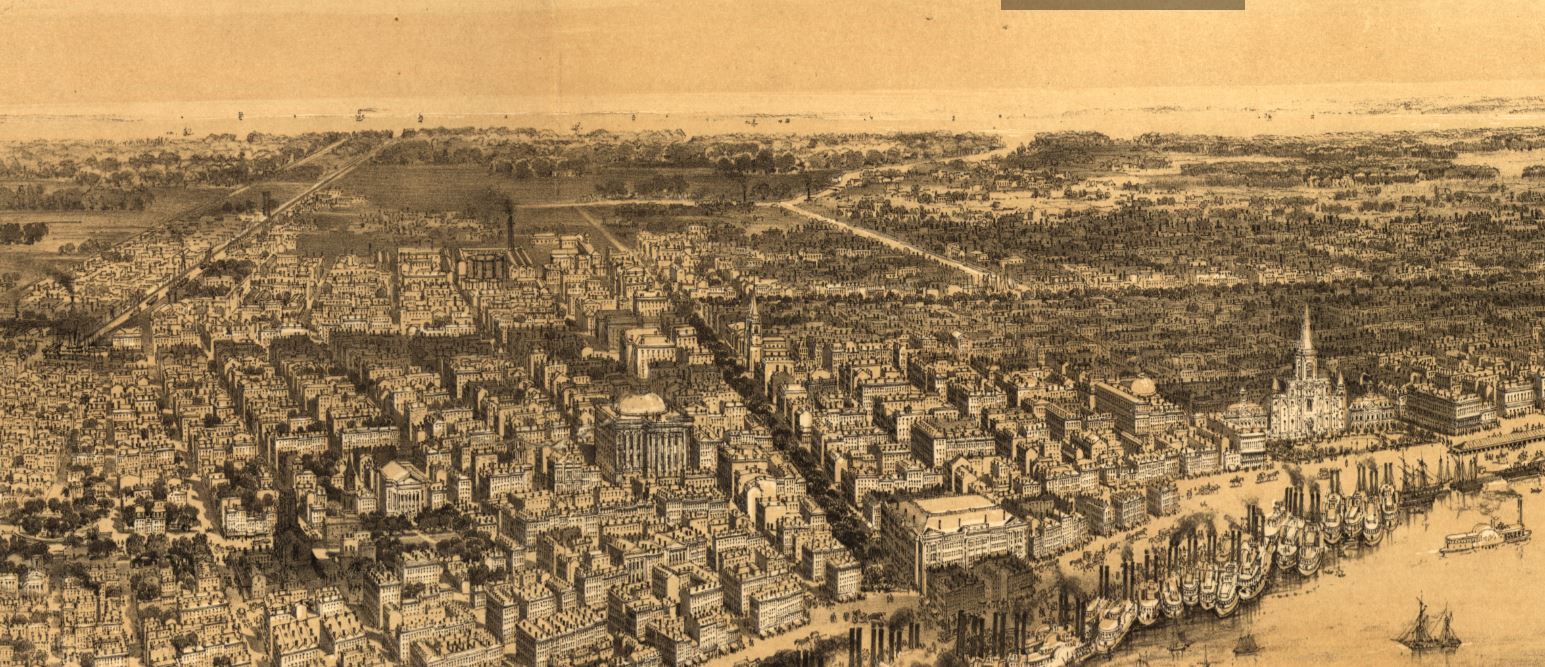

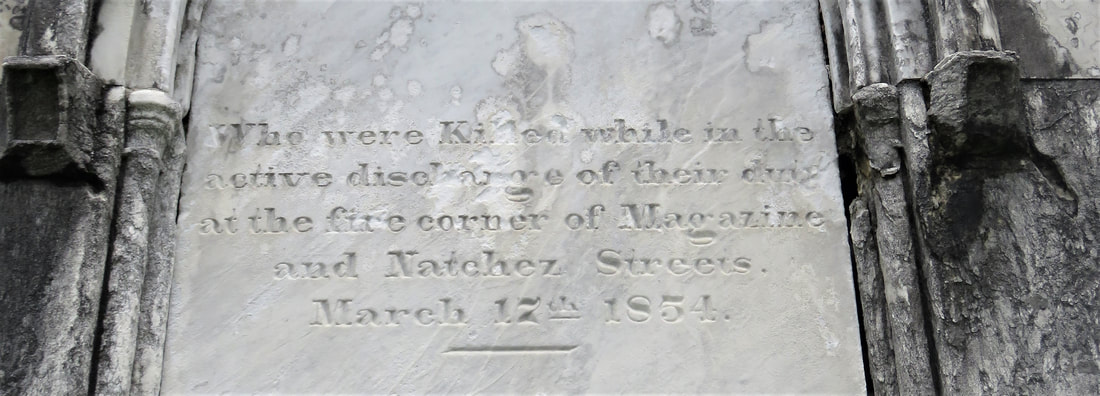

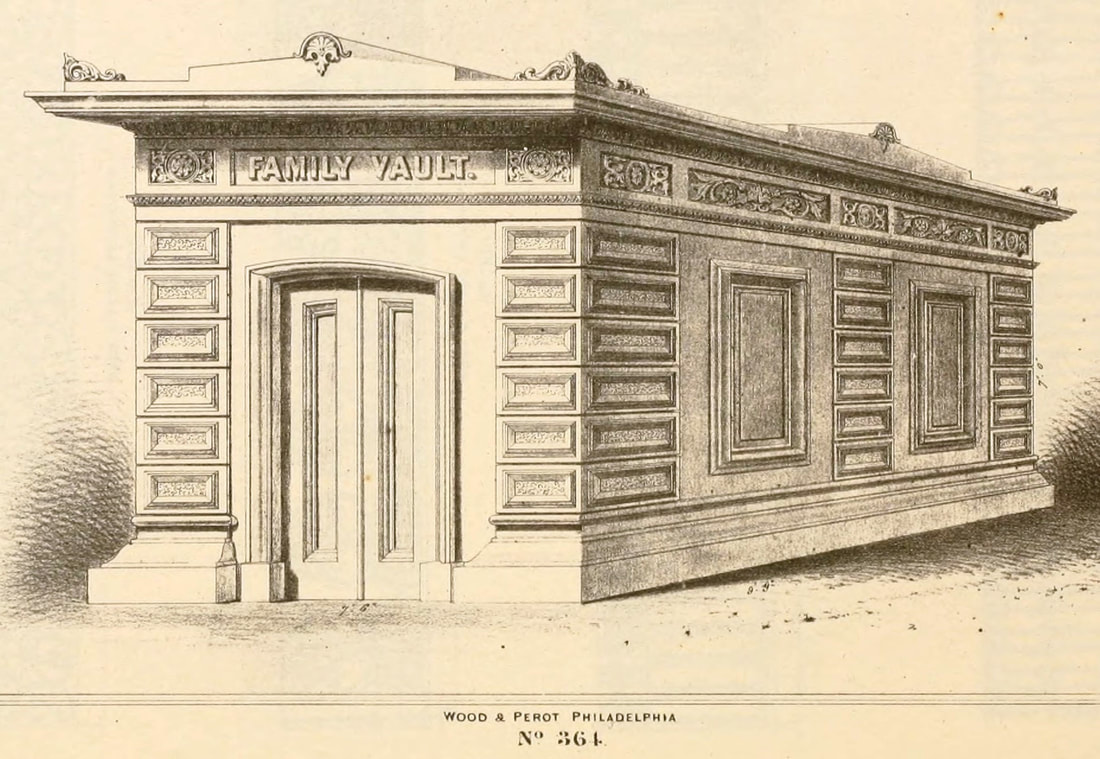

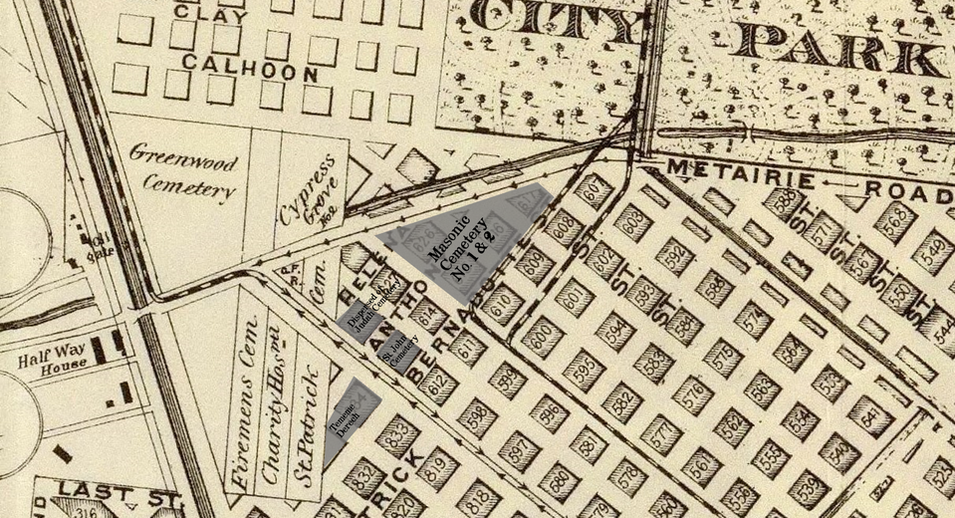

This is Part Three in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here and Part Two here. 1852: Greenwood Cemetery By 1850 the terminus of Canal Street remained mostly undeveloped. On each side of Canal approaching Bayou Metairie were the predominantly belowground Dispersed of Judah, St. Patrick’s, and Charity Hospital Cemeteries, each likely bounded by wooden fences. Improvements like the Halfway House, the Toll House, and the walls of Odd Fellows Rest modestly framed the monumental entryway to Cypress Grove Cemetery. Cypress Grove itself was more than a decade old and flourishing as a garden cemetery full of trees and landscape features – despite a fire in 1848 that destroyed many plantings.[1] The Firemen’s Charitable Association had been quite successful in developing Cypress Grove, so much so that demand for lots overran supply. In 1852, the FCA opened Greenwood Cemetery across Bayou Metairie from both Odd Fellows and Cypress Grove. Its eastern boundary would adjoin Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also known as Charity Hospital No. 2. In some ways, Greenwood Cemetery would be a continuation of Cypress Grove – dedicated to the memorial of fallen firemen and stylistically influenced by Anglo-Protestant aesthetics over those of Creole New Orleaneans. In fact, it’s likely no accident that Greenwood Cemetery shared its name with a famous garden cemetery in New York, founded in 1838. However, Greenwood would not accommodate the landscape features and lofty architecture so well fostered by Cypress Grove. Instead, the new Firemen’s cemetery would be organized in compact, neat rows that mirrored the kind of order seen in contemporary cemeteries like St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 on Esplanade Avenue (est. 1854). A grand dedication ceremony like those seen at Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows Rest would not be held for Greenwood Cemetery. This may have been the result of an almost immediate cholera and yellow fever epidemic following the cemetery’s opening. The 1853 yellow fever epidemic would kill as many as 12,000 people in New Orleans, quickly making Greenwood a vital burial ground. Unlike Cypress Grove or Odd Fellows Rest, Greenwood Cemetery was not enclosed with a masonry wall, but an iron fence. This left the southern boundary of the cemetery visually open to the bayou that meandered in front of it. The grassy space left room for display of more impressive monuments. Decades would pass, however, before the most iconic monuments of Greenwood would appear. The Confederate monument (1873), Firemen’s monument (1887), and Elk’s Lodge tumulus (1911) did not yet rise above the bayou. Instead, one of the first monuments to be erected in Greenwood Cemetery would be that of two martyred firefighters. On March 16, 1854, Daniel Woodruff and William McLeod responded to a fire on Magazine Street as members of Mississippi Fire Company No. 2. In the blaze, a wall fell upon Daniel Woodruff and he was killed in action. Later, William McLeod died of injuries sustained in the fire.[2] Exactly one year after the tragic fire, the FCA laid the cornerstone of the fallen men’s memorial tomb. The Firemen traveled to Greenwood Cemetery in a procession to Metairie Ridge where the cornerstone was laid. In Masonic tradition, the architect of the tomb, Sheppard Reynolds, presented the Grand Master of the FCA with a plumb, square, and level with which to test the cornerstone. After it was pronounced level and plumb, the stone was anointed using vessels of corn, wine, and oil. After an oratory, the procession retreated.[3] The Woodruff-McLeod tomb, similar in style but not size to the Teutonia Lodge tomb, was completed by stonecutter and tomb builder Newton Richards (1805 – 1874), who also constructed the Irad Ferry monument. Each arched loggia-like vault memorializes the life and service of Woodruff and McLeod. Yet only one of the two martyrs are actually buried in this tomb. When the time came to re-inter William McLeod in Greenwood his widow objected. His body remained at Girod Street Cemetery. It is unclear where McLeod may have been re-interred after the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery in 1957.[4] Newton Richards had by 1859 constructed the Irad Ferry monument, the Woodruff-McLeod monument, dozens of other tombs in New Orleans cemeteries, and even the granite pedestal atop which the Andrew Jackson statue is mounted in Jackson Square.[5] A man from New Hampshire who specialized in granite monuments, Richards was especially active in the Anglo-Northern associated cemeteries. In 1859, he would once again shape the budding landscape of Greenwood Cemetery by erecting the memorial of former New Orleans mayor Abidel Daily Crossman in Greenwood Cemetery. A.D. Crossman served four consecutive terms as mayor of New Orleans, weathering the city through natural disasters like Sauve’s Crevasse and the 1853 yellow fever epidemic. He oversaw the re-joining of the city from three separate municipalities into one united city government, and local military response to the Mexican-American War. Crossman was from Massachusetts and had long been a friend of the city’s firefighters – serving as a firefighter himself under Eagle Company No. 7.[6] For Crossman, Richards erected a classical Doric column carved of granite and surmounted with an urn. The granite die and stacked bases atop which the column sits are enclosed with cast iron fencing, the corners of which are each topped with cast iron flaming lamps. The cemeteries at the end of Canal Street were tied not only by geography but, in some cases, mutual origins and culture, specifically that of Northern-born Americans. For this reason, it is no surprise that stonecutters and tomb builders with similar backgrounds tended to concentrate their work in Cypress Grove, Greenwood, and Odd Fellows. In fact, the first sexton of Greenwood Cemetery, Daniel Merritt, also served as sexton in Odd Fellows Rest. Carved tablets signed by Merritt are found in all three cemeteries.[7] Greenwood Cemetery greeted a peculiar new tomb construction in the 1860s – tombs built of brick and mortar but clad in cast-iron panels. This style was not exclusive to Greenwood (Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 had the Karstendiek tomb by 1866, and Cypress Grove famously houses the Leeds cast-iron tomb), but Greenwood gathered the highest concentration of these unique structures. Four of these tombs (Marks, Enberger, Summers, and Hetion) were identical catalog-order tombs from the ironwork firm of Wood, Miltenberger, and Company, which had a branch in New Orleans. The Edwards tomb, also of cast iron, was a custom construction erected in 1861 across the aisle from the Woodruff and McLeod tomb. 1858: Tememe Derech Cemetery Jewish immigration to New Orleans continued through the first half of the nineteenth century. Some Jews emigrated from France, Germany, and the contested territory of Alsace-Lorraine between the two countries. By the 1850s, however, other Jewish people from Eastern Europe began to arrive, fleeing pogroms in their home countries. In 1858, Polish Jews formed the Orthodox congregation of Tememe Derech (“The Right Way”). This congregation was the first Eastern European Jewish congregation to construct a purpose-built synagogue, once on Carondelet Street. Tememe Derech also established its own cemetery across Canal Street from Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, on what is now Botinelli Place.[8] Tememe Derech was not the only Eastern European Jewish congregation in nineteenth century New Orleans. Over time, other congregations formed and merged, and Tememe Derech itself merged with others in 1904 to form Beth Israel Congregation. The new congregation constructed a synagogue on Carondelet Street and designed by Emile Weil. This building is now the New Home Family Worship Center at 1616 Carondelet.[9] As congregations formed and merged among Eastern European Jews in New Orleans, Tememe Derech’s original cemetery would become the burying ground for other congregations, namely Chevra Thilim and later Beth Israel. In 1916, Beth Israel would construct a Metaher house (a traditional chapel for the cleansing of bodies) at the entrance to the Canal Street cemetery. This structure was demolished in the 1960s.[10] The 1860s: A Decade of Change With the addition of Greenwood and Tememe Derech Cemeteries in the 1850s, the confluence of Canal Street, New Basin Canal, and Bayou Metairie had six cemeteries within its bounds. In 1854, New Orleans City Park was founded. Larger than New York’s Central Park and home to the largest concentration of old-growth live oak trees in the world, City Park would add to the character of this area as a place of diversion and rural retreat. A portion of Bayou Metairie running through City Park would eventually be closed off to become a park lagoon. Today, this lagoon is the last remaining vestige of Bayou Metairie. New Orleans as a city was growing in both population and urbanized area. In 1861, the New Orleans City Railroad Company constructed a rail line extending up Canal Street from its foot at the Mississippi River all the way to Bayou Metairie, expanding access and development. The next year, the second fraternal cemetery in the area would arrive when Masonic Cemetery No. 1 and 2 opened at Bienville Street and Bayou Metairie. Despite steady development in the area, it would not escape the humbling effects of natural forces. Metairie Ridge had escaped the flooding of Sauve’s Crevasse in 1849, but would not be so lucky in 1860, when both New Basin and Carondelet Canals overflowed their levies and flooded the area.[11] Another crevasse in 1871 would inundate the cemeteries even more, when the New Basin Canal levy breached at the Halfway House, causing water to flow into the cemeteries.[12] By 1862, additional railroad track was present running alongside Bayou Metairie to the Halfway House. Through the Civil War and into the 1870s, New Orleans’ street grid would encroach toward the cemeteries. Nearby City Park, home to the famous “dueling oaks,” would not be the only venue for such bouts. In 1868, a duel between a Mr. “M” and a Mr. “G” was fought near the Halfway House with swords as the chosen weapon. Although neither man died in the match, neighbors in the vicinity soon afterward requested a police station be placed at the Halfway House – a request that the city council granted.[13] 1867: St. John Cemetery Another cemetery would join the landscape of Canal Street in 1867. Founded by German St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church, St. John Cemetery was the second Protestant cemetery in New Orleans (the first was Episcopal Girod Street Cemetery, founded 1822). St. John Cemetery was owned and managed by the church through the nineteenth century and was religiously restricted. Wrote Leonard Victor Huber, who later co-owned the cemetery with his family, under the church’s ownership “secret societies were not allowed to hold ceremonies in it, and Catholic priests were forbidden by their bishops to officiate services in it.”[14] St. John Cemetery was managed by a sexton who lived on the grounds. The small cemetery at Canal and Bernadotte Streets would develop over time into a typical New Orleans cemetery until the 1920s, when circumstances would transform it into a completely different type of cemetery.[15] The Civil War New Orleans was captured by Union forces in late April 1862, early in the Civil War. The American Civil War was also a time in which the culture and practice of death changed nationwide. Soldiers, accustomed to the concept of a “good death” instead died on battlefields, often buried where they fell. In New Orleans, bodies of both Union and Confederate soldiers were received, transported from elsewhere and buried in places like Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 and Chalmette Cemetery in St. Bernard Parish. After the Civil War, questions of claiming and memorializing the dead dominated conversation. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also referred to as Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2, received the remains of both Federal and Confederate soldiers. In the 1870s, when the remains of Confederate soldiers were relocated from Chalmette Cemetery to Greenwood Cemetery, remains from other cemeteries including Cypress Grove No. 2 were reinterred in the same place. This effort was headed by the Ladies Benevolent Association of New Orleans, who erected the Greenwood Confederate monument atop this mass grave of 600 soldiers in 1873. The “Old Soldier’s Home,” established in 1866 by the State of Louisiana for Confederate veterans, also had a society tomb in Greenwood Cemetery by 1868. Remains of Union soldiers were also removed from Cypress Grove No. 2, as well. In the 1920s, as the old potter’s field was beginning to be redeveloped as a road and dumping ground, Federal soldiers were disinterred from Cypress Grove No. 2 and relocated to Chalmette National Cemetery. On All Saints’ Day, November 1, 1868, New Orleaneans observed the yearly tradition of decorating and visiting graves. The New Orleans Republican offered a glimpse of the Canal Street cemeteries on this day, noting the “noble monuments” of Cypress Grove, and nodding to the society tombs of the Deutscher Louisiana Draymen Verein (now mostly demolished), and the New Orleans Typographical Union in Greenwood Cemetery. Odd Fellows was described as well, “with its specious avenues bordered with trees and lined with the tombs of good and charitable men, is one of the most attractive of the homes of the dead.”[16] The rural cemeteries at Canal and City Park Avenue had matured into landscapes of marble, granite, limewash, and green landscaping. Each cemetery enclosed by masonry walls, picket fences, or painted ironwork, they framed canal and bayou as carriages and barges passed through. As much as the landscape had changed over three decades since the New Basin Canal opened, it was about to transform even further with the founding of an entirely new cemetery, the likes of which the city of New Orleans had yet to see. [1] Thomas O’Conner, editor, History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: Thomas O’Conner, 1891), 75.

[2] O’Conner, 84-85. [3] “Woodruff and McLeod Monument,” Daily Picayune, March 18, 1855. [4] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 39. [5] “Inauguration of the Equestrian Statue of Andrew Jackson,” Daily Picayune, February 9, 1856, 2. [6] O’Connor, 127. [7] “Firemen’s Charitable Association, Cypress Grove and Greenwood Cemeteries,” Daily Picayune, June 17, 1855; “Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, January 21, 1862. [8] Catherine C. Kahn and Irwin Lachoff, Images of America: The Jewish Community of New Orleans (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 24; The Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, “History of Orthodox Congregations in New Orleans.” http://www.msje.org/history/archive/la/HistoryofOrthodoxCongregations.htm [Accessed September 10, 2017] [9] Barry Stiefel and Emily Ford, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012), 47, 77-80. [10] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 22-23. [11] “Overflow of Canals,” Daily Crescent, October 4, 1860, 1. [12] “The Last Great Flood: Rear of the City Submerged,” New Orleans Republican, June 4, 1871, 1. [13] “Dueling,” New Orleans Republican, May 30, 1868, 3; “To the Common Council of the City of New Orleans,” New Orleans Republican, May 31, 1868. [14] Huber, et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol III: The Cemeteries, 47-48. [15] Ibid. [16] “All Saints Day,” New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1868, 1. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly