|

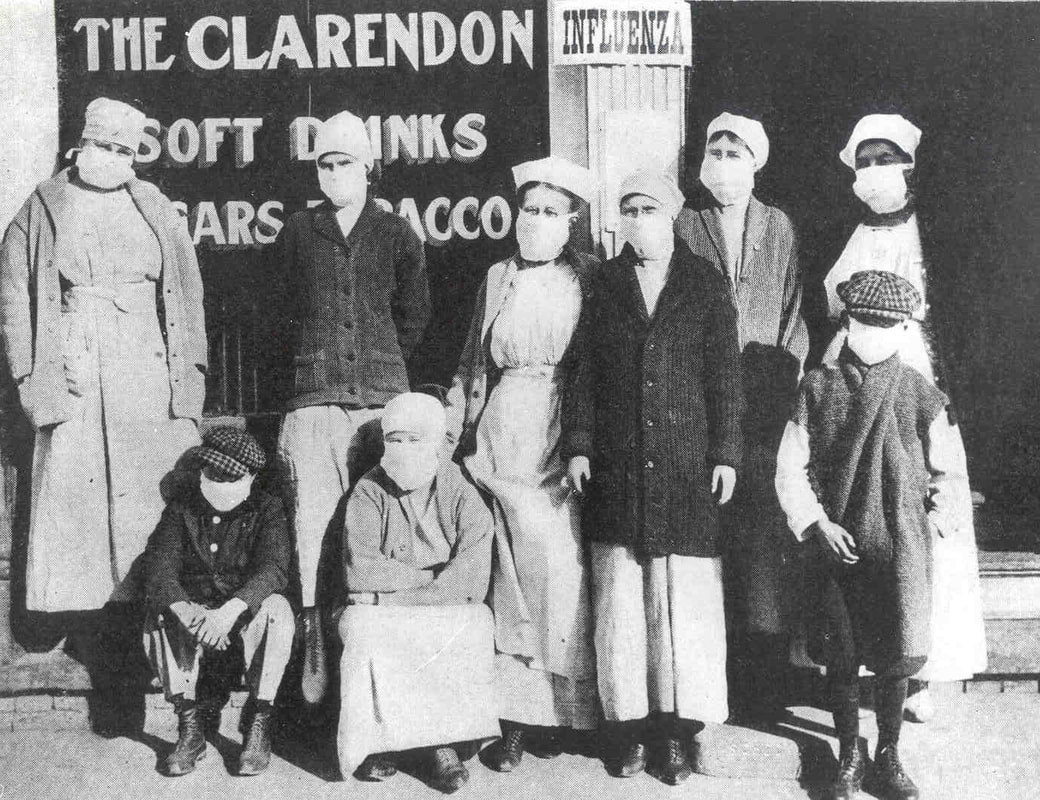

How New Orleans weathered one of the greatest plagues in history. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a worldwide emergency like that which took place in 1918. Modern-day fiction and sci-fi writers have materialized similar fears – there is no shortage of post-pandemic fiction. For example, the HBO series The Leftovers posits a world in which two percent of the world’s population has vanished, the Max Brooks novel World War Z injects zombies into a frighteningly realistic image of how civilization would handle pandemic catastrophe. The list goes on. But we so often forget that something like this did happen. In 1918, a strain of pandemic influenza swept the globe three times, infecting millions and killing five percent of the world’s population. Medical science today cannot pin down exactly where it began. One prominent theory states that H1N1 influenza began with swine farms in Haskell County, Kansas in late January 1918.[1] Like other incidents of mutated influenza virus “jumping” from livestock to humans, it could have fizzled out in the local population. Yet nationwide mobilization in response to the United States’ entry into World War I meant that military camps were ubiquitous and population movement intensified. Influenza was transported to Camp Funston, Kansas, where it spread to other camps, other towns. The first wave of influenza traveled from the United States to Brest, France, in April 1918. Within the next month, it spread to Spain. Spain, neutral during World War I, was less likely to censor press reports of the disease. Hence, although the U.S., Britain, and France saw just as many cases of influenza, such incidents were not reported. The uneven press coverage created the appearance of the disease originating in Spain, giving it the incorrect moniker “Spanish Influenza.[2]” Influenza was documented in China and India by May 1918. The spring wave, however, was comparatively mild. The second wave of Fall 1918 would be devastating. As the summer of 1918 wore on and Allied victories in Europe continued, state and federal medical officials assumed disaster had been averted.

Attempts to quarantine the sick and curb the spread of influenza were often thwarted by the pressures of total war. In one especially salient instance, insistence from upper-crust social circles in Philadelphia caused medical leaders to allow a War Bonds parade to take place, despite the mounting evidence of an influenza epidemic. New cases of the illness soared in the days after this large public gathering. In metropolitan areas, the flu jumped from military to civilian populations, and then spread.

One hundred years ago this month, influenza arrived in New Orleans.

5 Comments

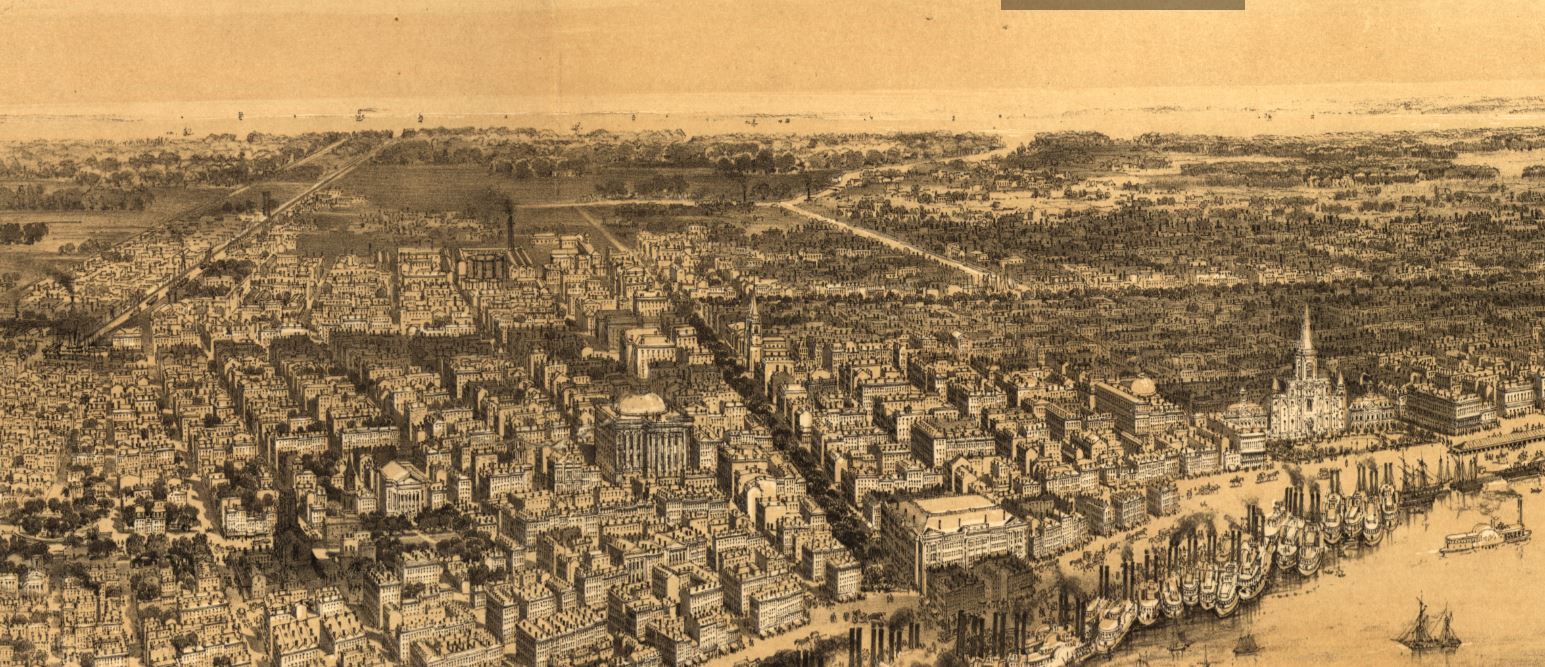

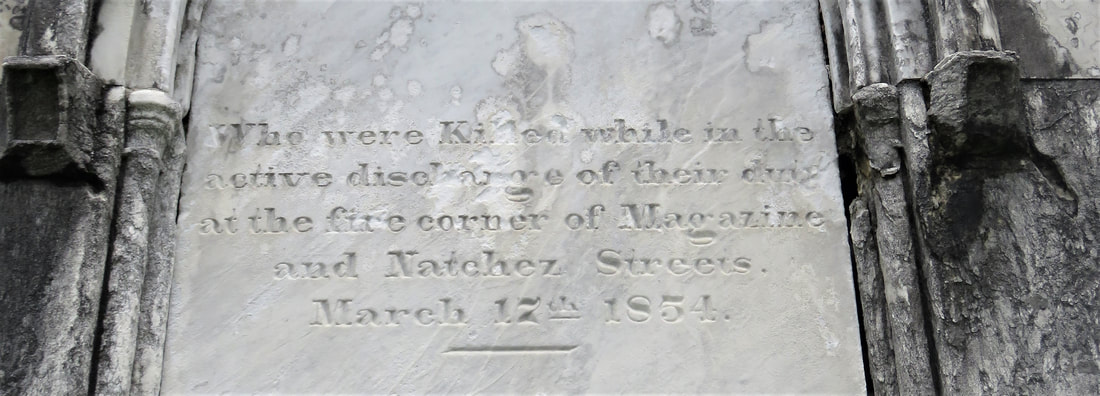

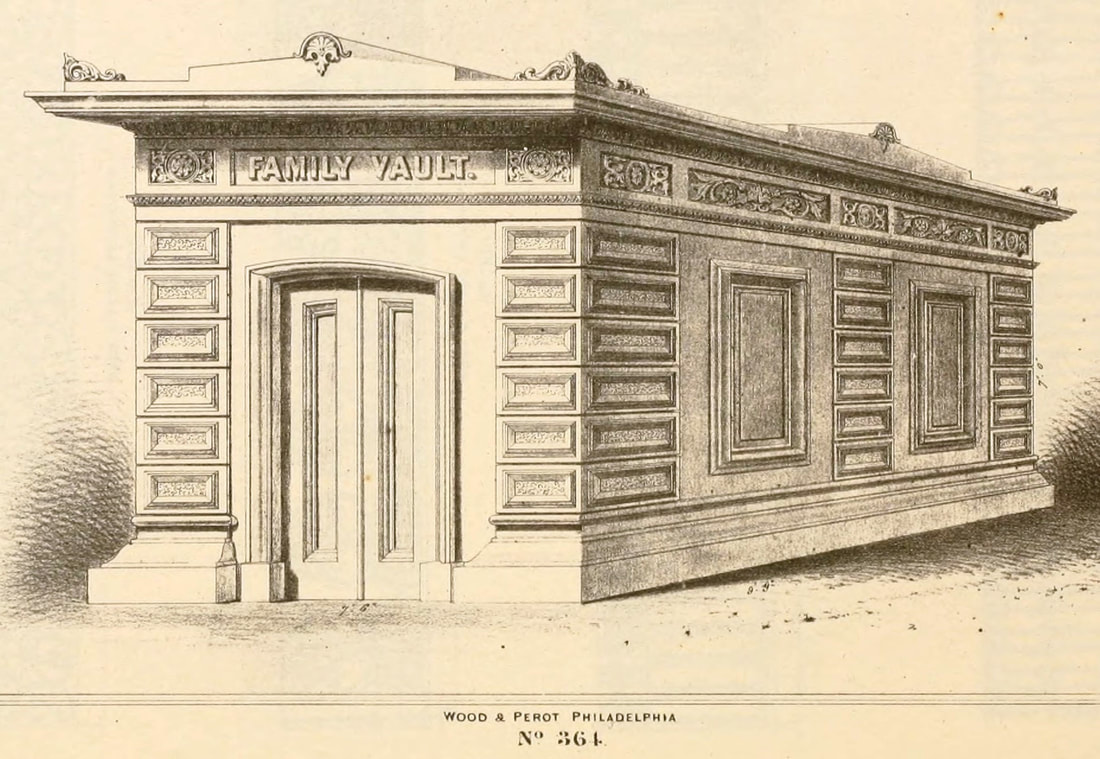

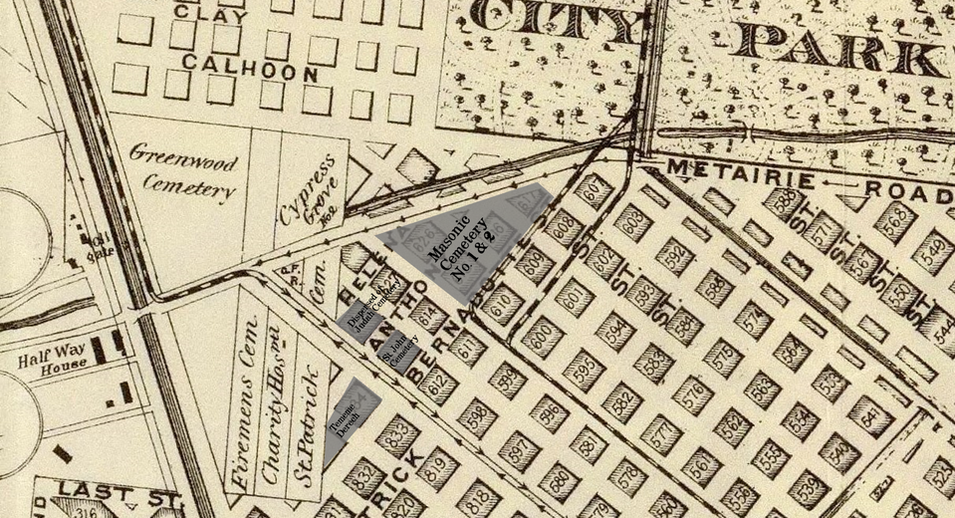

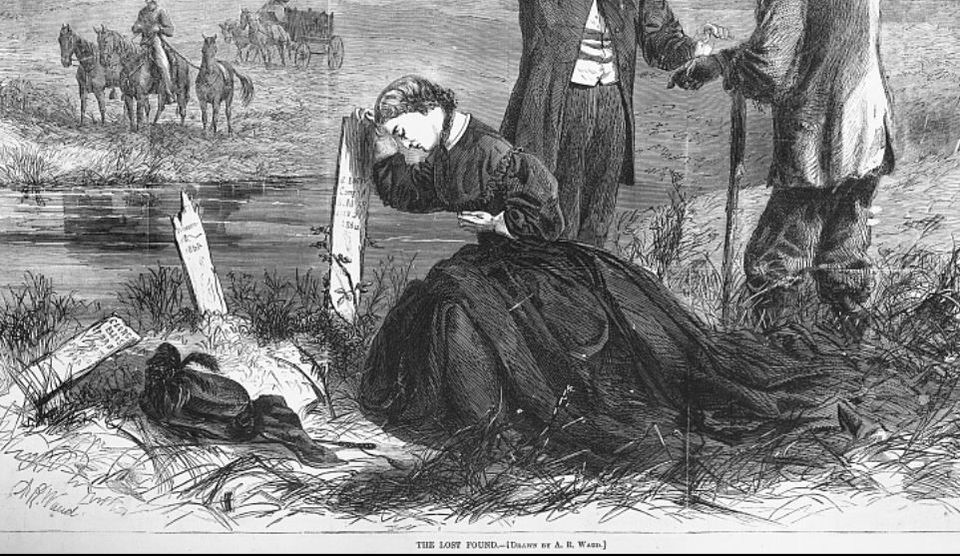

This is Part Three in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here and Part Two here. 1852: Greenwood Cemetery By 1850 the terminus of Canal Street remained mostly undeveloped. On each side of Canal approaching Bayou Metairie were the predominantly belowground Dispersed of Judah, St. Patrick’s, and Charity Hospital Cemeteries, each likely bounded by wooden fences. Improvements like the Halfway House, the Toll House, and the walls of Odd Fellows Rest modestly framed the monumental entryway to Cypress Grove Cemetery. Cypress Grove itself was more than a decade old and flourishing as a garden cemetery full of trees and landscape features – despite a fire in 1848 that destroyed many plantings.[1] The Firemen’s Charitable Association had been quite successful in developing Cypress Grove, so much so that demand for lots overran supply. In 1852, the FCA opened Greenwood Cemetery across Bayou Metairie from both Odd Fellows and Cypress Grove. Its eastern boundary would adjoin Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also known as Charity Hospital No. 2. In some ways, Greenwood Cemetery would be a continuation of Cypress Grove – dedicated to the memorial of fallen firemen and stylistically influenced by Anglo-Protestant aesthetics over those of Creole New Orleaneans. In fact, it’s likely no accident that Greenwood Cemetery shared its name with a famous garden cemetery in New York, founded in 1838. However, Greenwood would not accommodate the landscape features and lofty architecture so well fostered by Cypress Grove. Instead, the new Firemen’s cemetery would be organized in compact, neat rows that mirrored the kind of order seen in contemporary cemeteries like St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 on Esplanade Avenue (est. 1854). A grand dedication ceremony like those seen at Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows Rest would not be held for Greenwood Cemetery. This may have been the result of an almost immediate cholera and yellow fever epidemic following the cemetery’s opening. The 1853 yellow fever epidemic would kill as many as 12,000 people in New Orleans, quickly making Greenwood a vital burial ground. Unlike Cypress Grove or Odd Fellows Rest, Greenwood Cemetery was not enclosed with a masonry wall, but an iron fence. This left the southern boundary of the cemetery visually open to the bayou that meandered in front of it. The grassy space left room for display of more impressive monuments. Decades would pass, however, before the most iconic monuments of Greenwood would appear. The Confederate monument (1873), Firemen’s monument (1887), and Elk’s Lodge tumulus (1911) did not yet rise above the bayou. Instead, one of the first monuments to be erected in Greenwood Cemetery would be that of two martyred firefighters. On March 16, 1854, Daniel Woodruff and William McLeod responded to a fire on Magazine Street as members of Mississippi Fire Company No. 2. In the blaze, a wall fell upon Daniel Woodruff and he was killed in action. Later, William McLeod died of injuries sustained in the fire.[2] Exactly one year after the tragic fire, the FCA laid the cornerstone of the fallen men’s memorial tomb. The Firemen traveled to Greenwood Cemetery in a procession to Metairie Ridge where the cornerstone was laid. In Masonic tradition, the architect of the tomb, Sheppard Reynolds, presented the Grand Master of the FCA with a plumb, square, and level with which to test the cornerstone. After it was pronounced level and plumb, the stone was anointed using vessels of corn, wine, and oil. After an oratory, the procession retreated.[3] The Woodruff-McLeod tomb, similar in style but not size to the Teutonia Lodge tomb, was completed by stonecutter and tomb builder Newton Richards (1805 – 1874), who also constructed the Irad Ferry monument. Each arched loggia-like vault memorializes the life and service of Woodruff and McLeod. Yet only one of the two martyrs are actually buried in this tomb. When the time came to re-inter William McLeod in Greenwood his widow objected. His body remained at Girod Street Cemetery. It is unclear where McLeod may have been re-interred after the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery in 1957.[4] Newton Richards had by 1859 constructed the Irad Ferry monument, the Woodruff-McLeod monument, dozens of other tombs in New Orleans cemeteries, and even the granite pedestal atop which the Andrew Jackson statue is mounted in Jackson Square.[5] A man from New Hampshire who specialized in granite monuments, Richards was especially active in the Anglo-Northern associated cemeteries. In 1859, he would once again shape the budding landscape of Greenwood Cemetery by erecting the memorial of former New Orleans mayor Abidel Daily Crossman in Greenwood Cemetery. A.D. Crossman served four consecutive terms as mayor of New Orleans, weathering the city through natural disasters like Sauve’s Crevasse and the 1853 yellow fever epidemic. He oversaw the re-joining of the city from three separate municipalities into one united city government, and local military response to the Mexican-American War. Crossman was from Massachusetts and had long been a friend of the city’s firefighters – serving as a firefighter himself under Eagle Company No. 7.[6] For Crossman, Richards erected a classical Doric column carved of granite and surmounted with an urn. The granite die and stacked bases atop which the column sits are enclosed with cast iron fencing, the corners of which are each topped with cast iron flaming lamps. The cemeteries at the end of Canal Street were tied not only by geography but, in some cases, mutual origins and culture, specifically that of Northern-born Americans. For this reason, it is no surprise that stonecutters and tomb builders with similar backgrounds tended to concentrate their work in Cypress Grove, Greenwood, and Odd Fellows. In fact, the first sexton of Greenwood Cemetery, Daniel Merritt, also served as sexton in Odd Fellows Rest. Carved tablets signed by Merritt are found in all three cemeteries.[7] Greenwood Cemetery greeted a peculiar new tomb construction in the 1860s – tombs built of brick and mortar but clad in cast-iron panels. This style was not exclusive to Greenwood (Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 had the Karstendiek tomb by 1866, and Cypress Grove famously houses the Leeds cast-iron tomb), but Greenwood gathered the highest concentration of these unique structures. Four of these tombs (Marks, Enberger, Summers, and Hetion) were identical catalog-order tombs from the ironwork firm of Wood, Miltenberger, and Company, which had a branch in New Orleans. The Edwards tomb, also of cast iron, was a custom construction erected in 1861 across the aisle from the Woodruff and McLeod tomb. 1858: Tememe Derech Cemetery Jewish immigration to New Orleans continued through the first half of the nineteenth century. Some Jews emigrated from France, Germany, and the contested territory of Alsace-Lorraine between the two countries. By the 1850s, however, other Jewish people from Eastern Europe began to arrive, fleeing pogroms in their home countries. In 1858, Polish Jews formed the Orthodox congregation of Tememe Derech (“The Right Way”). This congregation was the first Eastern European Jewish congregation to construct a purpose-built synagogue, once on Carondelet Street. Tememe Derech also established its own cemetery across Canal Street from Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, on what is now Botinelli Place.[8] Tememe Derech was not the only Eastern European Jewish congregation in nineteenth century New Orleans. Over time, other congregations formed and merged, and Tememe Derech itself merged with others in 1904 to form Beth Israel Congregation. The new congregation constructed a synagogue on Carondelet Street and designed by Emile Weil. This building is now the New Home Family Worship Center at 1616 Carondelet.[9] As congregations formed and merged among Eastern European Jews in New Orleans, Tememe Derech’s original cemetery would become the burying ground for other congregations, namely Chevra Thilim and later Beth Israel. In 1916, Beth Israel would construct a Metaher house (a traditional chapel for the cleansing of bodies) at the entrance to the Canal Street cemetery. This structure was demolished in the 1960s.[10] The 1860s: A Decade of Change With the addition of Greenwood and Tememe Derech Cemeteries in the 1850s, the confluence of Canal Street, New Basin Canal, and Bayou Metairie had six cemeteries within its bounds. In 1854, New Orleans City Park was founded. Larger than New York’s Central Park and home to the largest concentration of old-growth live oak trees in the world, City Park would add to the character of this area as a place of diversion and rural retreat. A portion of Bayou Metairie running through City Park would eventually be closed off to become a park lagoon. Today, this lagoon is the last remaining vestige of Bayou Metairie. New Orleans as a city was growing in both population and urbanized area. In 1861, the New Orleans City Railroad Company constructed a rail line extending up Canal Street from its foot at the Mississippi River all the way to Bayou Metairie, expanding access and development. The next year, the second fraternal cemetery in the area would arrive when Masonic Cemetery No. 1 and 2 opened at Bienville Street and Bayou Metairie. Despite steady development in the area, it would not escape the humbling effects of natural forces. Metairie Ridge had escaped the flooding of Sauve’s Crevasse in 1849, but would not be so lucky in 1860, when both New Basin and Carondelet Canals overflowed their levies and flooded the area.[11] Another crevasse in 1871 would inundate the cemeteries even more, when the New Basin Canal levy breached at the Halfway House, causing water to flow into the cemeteries.[12] By 1862, additional railroad track was present running alongside Bayou Metairie to the Halfway House. Through the Civil War and into the 1870s, New Orleans’ street grid would encroach toward the cemeteries. Nearby City Park, home to the famous “dueling oaks,” would not be the only venue for such bouts. In 1868, a duel between a Mr. “M” and a Mr. “G” was fought near the Halfway House with swords as the chosen weapon. Although neither man died in the match, neighbors in the vicinity soon afterward requested a police station be placed at the Halfway House – a request that the city council granted.[13] 1867: St. John Cemetery Another cemetery would join the landscape of Canal Street in 1867. Founded by German St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church, St. John Cemetery was the second Protestant cemetery in New Orleans (the first was Episcopal Girod Street Cemetery, founded 1822). St. John Cemetery was owned and managed by the church through the nineteenth century and was religiously restricted. Wrote Leonard Victor Huber, who later co-owned the cemetery with his family, under the church’s ownership “secret societies were not allowed to hold ceremonies in it, and Catholic priests were forbidden by their bishops to officiate services in it.”[14] St. John Cemetery was managed by a sexton who lived on the grounds. The small cemetery at Canal and Bernadotte Streets would develop over time into a typical New Orleans cemetery until the 1920s, when circumstances would transform it into a completely different type of cemetery.[15] The Civil War New Orleans was captured by Union forces in late April 1862, early in the Civil War. The American Civil War was also a time in which the culture and practice of death changed nationwide. Soldiers, accustomed to the concept of a “good death” instead died on battlefields, often buried where they fell. In New Orleans, bodies of both Union and Confederate soldiers were received, transported from elsewhere and buried in places like Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 and Chalmette Cemetery in St. Bernard Parish. After the Civil War, questions of claiming and memorializing the dead dominated conversation. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also referred to as Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2, received the remains of both Federal and Confederate soldiers. In the 1870s, when the remains of Confederate soldiers were relocated from Chalmette Cemetery to Greenwood Cemetery, remains from other cemeteries including Cypress Grove No. 2 were reinterred in the same place. This effort was headed by the Ladies Benevolent Association of New Orleans, who erected the Greenwood Confederate monument atop this mass grave of 600 soldiers in 1873. The “Old Soldier’s Home,” established in 1866 by the State of Louisiana for Confederate veterans, also had a society tomb in Greenwood Cemetery by 1868. Remains of Union soldiers were also removed from Cypress Grove No. 2, as well. In the 1920s, as the old potter’s field was beginning to be redeveloped as a road and dumping ground, Federal soldiers were disinterred from Cypress Grove No. 2 and relocated to Chalmette National Cemetery. On All Saints’ Day, November 1, 1868, New Orleaneans observed the yearly tradition of decorating and visiting graves. The New Orleans Republican offered a glimpse of the Canal Street cemeteries on this day, noting the “noble monuments” of Cypress Grove, and nodding to the society tombs of the Deutscher Louisiana Draymen Verein (now mostly demolished), and the New Orleans Typographical Union in Greenwood Cemetery. Odd Fellows was described as well, “with its specious avenues bordered with trees and lined with the tombs of good and charitable men, is one of the most attractive of the homes of the dead.”[16] The rural cemeteries at Canal and City Park Avenue had matured into landscapes of marble, granite, limewash, and green landscaping. Each cemetery enclosed by masonry walls, picket fences, or painted ironwork, they framed canal and bayou as carriages and barges passed through. As much as the landscape had changed over three decades since the New Basin Canal opened, it was about to transform even further with the founding of an entirely new cemetery, the likes of which the city of New Orleans had yet to see. [1] Thomas O’Conner, editor, History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: Thomas O’Conner, 1891), 75.

[2] O’Conner, 84-85. [3] “Woodruff and McLeod Monument,” Daily Picayune, March 18, 1855. [4] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 39. [5] “Inauguration of the Equestrian Statue of Andrew Jackson,” Daily Picayune, February 9, 1856, 2. [6] O’Connor, 127. [7] “Firemen’s Charitable Association, Cypress Grove and Greenwood Cemeteries,” Daily Picayune, June 17, 1855; “Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, January 21, 1862. [8] Catherine C. Kahn and Irwin Lachoff, Images of America: The Jewish Community of New Orleans (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 24; The Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, “History of Orthodox Congregations in New Orleans.” http://www.msje.org/history/archive/la/HistoryofOrthodoxCongregations.htm [Accessed September 10, 2017] [9] Barry Stiefel and Emily Ford, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012), 47, 77-80. [10] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 22-23. [11] “Overflow of Canals,” Daily Crescent, October 4, 1860, 1. [12] “The Last Great Flood: Rear of the City Submerged,” New Orleans Republican, June 4, 1871, 1. [13] “Dueling,” New Orleans Republican, May 30, 1868, 3; “To the Common Council of the City of New Orleans,” New Orleans Republican, May 31, 1868. [14] Huber, et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol III: The Cemeteries, 47-48. [15] Ibid. [16] “All Saints Day,” New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1868, 1. 2016 is already shaping up to be a great year for Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. More than ever before, we’ve had such exciting opportunities to share our research and knowledge of New Orleans cemetery preservation with others. This week, we presented to the Louisiana Historical Association annual conference in Baton Rouge. If you enjoyed this presentation (or if you missed it) you can catch us at these upcoming speaking events and volunteer opportunities.

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC will also be participating in a number of presentations this year. On June 1-4, we will be participating in the national conference of the Vernacular Architecture Forum (VAF), in Durham, North Carolina. There, with Dr. Peter Dedek of Texas State University, we will present to conference attendees on the contribution of African American labor organizations to the architecture of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. If you can’t make it to North Carolina, you can check out our brief synopsis on the topic here. On September 15, Oak and Laurel will have the great pleasure of presenting to the Italian American Cultural Center. In this lecture, we will discuss the impact of Italian Americans on our New Orleans cemetery landscapes. Learn more here. There are some other events coming up that we can’t wait to attend! On Saturday, April 16, author of recently published New Orleans cemetery opus Death Embraced, Mary Lacoste, will present to the conference of the International Cemetery, Cremation, and Funeral Association in New Orleans. The conference will be a great gathering of professionals in the funerary industry, and we’re excited to see Mary bring some New Orleans flavor to the event. Death Embraced is available at many local New Orleans bookstores, as well.

On April 27, we’re looking forward to seeing Dr. Daniele Maras of Columbia University present at Loyola University in a lecture entitled, “A Way to Immortality: Greek Myths of Divinization and Etruscan Funerary Rituals.” Check out details here. 2016 is going to be a great year for cemetery and funerary scholarship and research in New Orleans. We’ll see you out there among the tombs! |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly