|

Part Three of Three Brickmaking in the Late Nineteenth Century Expanding infrastructure and advancing technology led to a number of advances in brickmaking after the Civil War. These processes included dry-pressing, in which denser clay is compressed using steam-powered equipment, and extruding, in which the mold is abandoned for extruded clay cut with wires. In buildings, New Orleans saw entirely new materials like terra cotta and cast-iron storefronts. In New Orleans cemeteries, terra cotta was never established as a structural material. However, cast-iron companies like Wood, Miltenberger & Co. expanded their market by building catalog-ordered iron tombs. New Orleans has more than one dozen of these tombs remaining. In cemeteries, red river brick was almost entirely phased out, although many brickyards still produced them.[1] Many bricks found in tombs of this era show different variations in color, texture, and inclusions, but much are similar to “hard tans,” indicating sources in St. Tammany Parish. This is likely, as even more brickyards developed there after 1865.[2]  from the St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. Image courtesy Library of Congress. from the St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. Image courtesy Library of Congress. Among the St. Tammany brickyards to establish and grow in the late 19th century was St. Joe Brick Company. Founded in 1891, St. Joe Brick used (and still uses) wooden molds for brick manufacture. St. Joe bricks, are found throughout New Orleans cemeteries, where their porousness, dimension, and breathability suited tombs coated in lime stucco. Entire tombs were constructed using exclusively St. Joe Brick. Today, St. Joe bricks can still be purchased from the company’s Pearl River yard and other distributors. Like historic salvaged bricks, they mimic the qualities builders sought in historic building materials.[3] New Materials and Methods From the turn of the century, industrialized building materials inched further and further into the New Orleans cemetery landscape. Most notably, modern cements became more and more available until, after World War II, they were the norm. This meant Portland cement stucco replacing lime. But it also meant the rise of cast concrete, cast stone, and concrete block. A notable example of this was Dognibene Architectural Cast Stone, a company that seems to have dealt primarily with garden features and pottery, but also built tombs. Three Dognibene tombs are known to exist from the 1920s: Two in Hook and Ladder Cemetery (Gretna), and one in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Today, New Orleans bricks are more important to cemetery preservation than ever. Most historic tombs, especially those in need of repair or attention, require brick replacement, a difficult task in a world where traditional brickmaking is all but phased out. The desire for historic brick to be used in walls, paving, and historic buildings also put tombs at risk of brick theft, an incident that is all too common. Even more material is lost to unsympathetic repairs applied to soft brick which can constrict materials and cause cracking, breaking, or even structural failure.

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC only uses historically-appropriate brick for repairs. Where brick must be replaced, brick of similar density and dimension is chosen – we do not salvage bricks from other cemeteries or tombs. You never know who will come back to care for their historic burial place. [1] American Engineer, Vol. 16 (July 1888), 13. [2] “Tammany Steam Brick Yard,” Times Picayune, December 24, 1871, 15; “Lake Brick for Sale,” St. Tammany Farmer, October 24, 1908. [3] “History of St. Joe Brick Works,” http://www.stjoebrickworks.com/history.html; Dave Macnamara, “Heart of Louisiana: St. Joe Brick Works,” Fox 8 Live, January 11, 2013, http://www.fox8live.com/story/19517618/heart-of-louisiana-st-joe-brickworks.

1 Comment

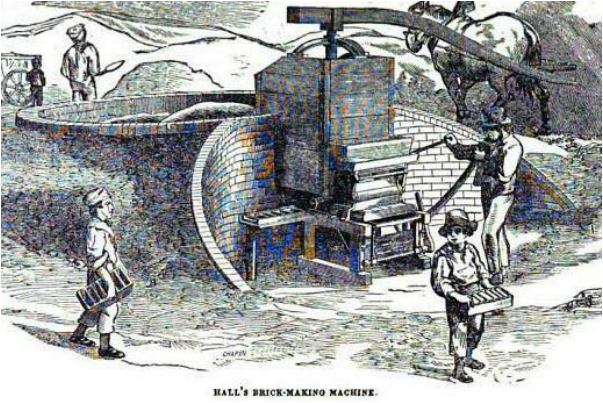

Part Two of Three The Little Red Row-house in the Cemetery By the 1830s, brickmaking processes were slowly industrializing in the Northeast and along the Eastern Seaboard. The introduction of hand-operated pressing machines led to the production of bricks with smoother edges. Other developments that tempered and cut clay using wires also arose. While these processes would eventually be introduced to New Orleans brickmakers, the clean, dense, fine-edged bricks they produced would be especially associated with northern cities like Philadelphia. In the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the “Protestant Section” is dominated by below-ground burials, a feature attributed to the cultural inclination of non-Catholics toward in-ground burial regardless of circumstances. Those burials which are accommodated by above-ground tombs are distinguished by construction using bricks that would sooner be at home in a northern row-house than a New Orleans tomb. The tombs of the Layton and Johnson families exhibit this brick for tomb construction. The tradition expanded beyond the 1830s, as exhibited by the multiple pressed red-brick tombs associated with Northern-born families in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Unlike traditional New Orleans tombs, these bricks were likely meant to be bare, without stucco. Brick Making Machines and Labor Beginning in the 1840s and likely earlier, brickmaking machines of all different types arose in New Orleans. The first machines were modifications of the “pug mill,” an apparatus by which brickmaking clay is churned and cured in order to make it suitable for molding. In 1848, John Hoey prominently advertised the construction of Hall’s “patent brickmaking machine” on his property near Bayou St. John.[1] This machine was essentially a pug mill in which clay was churned, cured, and extruded into molds. A number of additional brickyards developed along the Carondelet Canal, which ran from Bayou St. John past St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, terminating at Basin Street. Into the 1920s, “Carondelet Walk” featured a great deal of the city’s brick yards, from which bricks could be milled, fired, and transported for sale. Other brick yards thrived along the Mississippi River at Tchoupitoulas Street. In the Riverbend area, a brickyard operated a version of a Hoffman Kiln, another patented machine by which bricks were fired in a rotating sequence. By the 1850s, a number of steam-powered brick-making operations existed along the Gulf Coast in Biloxi, Mobile, and Thibodeaux, which supplied New Orleans markets.[1]

Prior to 1865, most of these operations, as well as smaller brick-making industries on plantation land, were operated by enslaved African Americans who were skilled in trade. In one instance, Gabriel Parker of St. Tammany Parish came to own his own brickyard after emancipation. In many other instances, freed tradesmen passed on their skills to their children.[2] [1] “Biloxi Fire Brick,” Daily Crescent, July 29, 1850, 3; Daily Picayune, June 3, 1866, 3; “Hoffman’s Brick Making Kiln,” Daily Picayune, March 8, 1867, 2; The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans Daily Picayune: 1903), 41; “Brickmaking Machine,” Thibodaux Minerva, January 21, 1854, 3. [2] Ellis, St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac, 159; Crary, J.W., Sixty Years a Brickmaker: A Practical Treatise on Brickmaking and Burning and the Management and Use of Different Kinds of Clays and Kilns for Burning Brick (Indianapolis: T.A. Randall & Co., 1890), 36. Labor Day was established in the 1880s as a holiday in which to appreciate and remember the contributions of organized labor in our communities. New Orleans is not always readily associated with labor history, but one walk through a quiet, historic cemetery and the significance of workingmen’s societies is clear. Established in 1850 along Washington Avenue at Saratoga Street, Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 is the site of many different expressions of the drive of individuals to organize and collect for the greater benefit. Social aid societies such as the Société Française de Bienfaisance et D'Assistance Mutuelle built tombs for their members here – tall, wide, multi-vault tombs into which numerous burials could be made at once. Members of these societies paid monthly or yearly dues, the benefits of which included a funeral, tomb burial, and often monetary support for widows and orphans. The most prominent of these societies in both history books and the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 is that of the Butchers’ Benevolent Society, who contracted James Hagan and L.E. Lohes to build their eighty-seven vault tomb in Square 19. It cost $5,000 and was completed in 1868.[1] The Butchers’ Benevolent Society charged its members each $1 in the event of a member’s death, the proceeds of which were given to surviving family. If any member failed to attend the burial of the deceased butcher, he was fined fifty cents (one dollar for board members). Members attending a butcher’s funeral were prohibited from smoking cigars and cigarettes while processing to the tomb, but were allowed to do so when processing away.[2] The Butcher’s association tomb is distinctive, but is not nearly the most significant aspect of the society’s history. Shortly after the dedication of the tomb, the Butchers’ Benevolent Association brought suit against the City of New Orleans in a case that challenged the interpretation of the newly-drafted Fourteenth Amendment. The Slaughterhouse Case became a landmark Supreme Court case in 1873, and continues to be argued and revisited today. The Slaughterhouse Case challenged the language of the Fourteenth Amendment, which was intended to establish the rights of emancipated slaves as the same rights, privileges and immunities of all American citizens. Beyond the Butchers’ tomb, the exercise of these rights by African American laborers is visible in high relief across the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. African-American Labor Societies Along the Sixth Street and Loyola Street fences of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 are numerous society tombs dedicated to the members of African American labor organizations. Many of them were associated with the transport, weighing, and moving of goods along New Orleans’ waterfront: the Coachmen Benevolent Association, the Teamsters and Loaders Union Benevolent Association, the Cotton Yardmen No. 2, and others. In the late 1870s and through the 1880s, these associations formed to protect the rights and opportunities available for African American workingmen. Organizations were racially segregated but frequently worked in tandem with white organizations. The Cotton Yardmen Benevolent Association No. 2 is an example of this. From Eric Arnesen’s Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: “Leading the new union drive was the white Cotton Yardmen’s Benevolent Association formed in December 1879 under the direction of Democratic party ward boss and Administrator of Police, Patrick Mealy; two years later it boasted a membership of 986 and a bank account of $13,000. Black cotton rollers, with the assistance of the leaders of the white yardmen, formed the Cotton Yardmen’s Benevolent Association No. 2, in January 1880, and both organizations agreed to work ‘in full harmony’ with each other. In April 1880, the black teamsters and loaders established their benevolent association, as did coal wheelers the following month…In September 1880, cotton weighers and reweighers formed a mutual aid association that aimed to secure a uniform system for weighing and re-weighing cotton and to regulate wages and arbitrate disputes.[3]” Organizations like those represented in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 navigated the twin hardships of labor injustice and racial prejudice. Yet the establishment of such unions was accomplished, despite acute awareness of the possibility of violence. Events like the 1887 Thibodaux Massacre and other bloody labor conflicts would have surely weighed upon laborers as they worked toward fair treatment.

While these treatments appear to offer a maintenance-free solution to crumbling tombs, such materials can be harmful to the soft brick beneath. Of the twenty-two society tombs of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, only a few are not abandoned, and active decay is the dominant force.

This Labor Day, we take part in the intention of this memorial architecture and appreciate the achievements that the society tombs of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 represent. For further reading: Daniel Rosenberg. New Orleans Dockworkers: Race, Labor, and Unionism 1892-1923. New York: SUNY Press, 1988. Eric Arnesen. Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: Race, Class, and Politics, 1863-1923. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994. Steve Striffler and Thomas Jessen Adams. Working in the Big Easy: The History and Politics of Labor in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: University of Louisiana Press, 2014. Paul D. Moreno. Black Americans and Organized Labor: A New History. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008. PBS: Landmark Supreme Court Cases related to Labor. New Orleans Dockworkers and Unionization, Wikipedia New Orleans 1892 General Strike, Wikipedia [1] New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1868, 1; “The Butchers’ Benevolent Association,” New Orleans Crescent, October 13, 1868.

[2] Butchers’ Benevolent Association, Constitution et règlements de la Société de bienfaisance des bouchers de la Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans: Imprimerie Franco-Americaine), 1883, Articles Fourteen and Sixteen. [3] Arneson, Eric, Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: Race, Class, and Politics, 1863-1923 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 61-63. Part One of Three “Reds” and “Tans” –hand-molded, wire-cut and pressed: Much can be learned from the bricks that comprise any one tomb. Brick identification can teach us about the construction date of the tomb, later alterations, quality of original construction, and cultural connections of the interred. It can help us understand the process of development in a cemetery, demolition and rebuilding, and where repairs were made. The history of New Orleans brick is as complex as its rich industrial and commercial history. However, the general narrative history of New Orleans brick is simple: “soft reds” were made from the clay of the Mississippi River, otherwise known as “batture,” and “hard tans” were made from the clays found around Lake Pontchartrain.[1] While this narrative is generally true, it belies the greater complexity of masonry in the Crescent City, in which new technologies and new commercial infrastructure compounded available brick types and styles. New Orleans River Brick New Orleans “soft reds” were likely the first masonry units manufactured in the city in the eighteenth century. Using the most basic and common of methods, brickmakers would mine batture from the river’s bank, allow it to dry, temper it, mold it, and fire it. Brick firing prior to the industrial revolution was almost exclusively accomplished without special equipment. Clay was molded in wooden molds, allowed to dry or cure, and then fired. These bricks can be bright or dull red, with soft edges. New Orleans “soft red” or “river brick” continued to be made through the nineteenth century. When we see red river brick in New Orleans cemeteries, their presence alone does not suggest early nineteenth century construction. However, soft reds are much more common in the oldest cemeteries in the city: St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, and to a lesser extent Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. We see them in single-vault step tombs, wall vaults, and other elements of cemetery landscapes that represent the earliest phases of construction. It should be mentioned here that, generally speaking, we should seldom see bricks at all. New Orleans reds are so soft that exposure to the humid elements and temperature cycles of our local climate can cause them to deteriorate. Historic craftsmen were aware of this and typically coated tombs with lime-based stucco, which protected the brick beneath. Stucco coating was also applied to hide the appearance of bricks which were irregular in size and edges and were not considered aesthetically pleasing.[2] “Lake” or St. Tammany Brick

New Orleans “tans,” historically referred to as “lake brick,” were similarly manufactured during the first half of the nineteenth century. Instead of river batture, they were created from clay sourced north and east of New Orleans. Typically, this meant deposits near Lake Pontchartrain, but a number of other sources in St. Tammany parish were also used.[1] The mineral content of St. Tammany clays produced a tan-colored brick, typically with dark inclusions of iron, bauxite, and other impurities. Such bricks were significantly more durable than river bricks.[2] While lake bricks became the standard for a great deal of city construction by the 1850s, there were no requirements for the construction of tombs. Alternately, city ordinance did require that all tombs be “plastered” with protective stucco, which meant that cheaper bricks could be utilized. For this reason it is not surprising that river bricks remained the norm in tomb construction until around the time of the Civil War. Hand-molded lake and river bricks were easily manufactured and acquired locally. Yet the hub of trade and growth that was nineteenth century New Orleans invited a great deal more in the way of building materials and masonry units. Furthermore, cemetery construction typically represents the aesthetic and construction tradition of the memorialized individual or individuals. The best example of this trend can be seen in the Protestant and other Northern-extracted cemeteries of the city.[3] [1] Ellis, Frederick S., St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1981, 108. [2] “An Ordinance to Establish a Ferry near the St. Mary’s Market, and Connected with the City of Lafayette,” True American, November 20, 1838, 1. [3] “Building Material, Bricks, Firewood,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, August 02, 1859, 4. Advertising brick from France, England, and America. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly