|

2016 was a momentous year – but in cemeteries worldwide, it was more or less average for incidences of vandalism. Every year, hundreds of cemeteries suffer crimes of toppled stones, graffiti, desecration of remains, and outright demolition. In the United States, this year at least 1,811 individual markers were affected, costing at least $488,000.[1] Cemetery vandalism is not rare or unusual. Its causes vary from adolescent antisocial behavior to politically, racially, or religiously motivated crimes. The only commonality among most instances of cemetery vandalism is the process through which the crime may have been prevented, and how its effects can be mitigated. While Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a New Orleans-based cemetery preservation company, worldwide cemetery vandalism is a special research interest. This blog post is based on an ongoing data collection project based on news reports of cemetery vandalism throughout the year. We catalog each incident, indexing for motivation, type of vandalism (knocked-over headstones, graffiti, theft of grave decorations, etc.), location, and whether an offender is identified and prosecuted. Reports originate primarily in the English-speaking world (United States, Canada, UK, Ireland), but often include English-language reports from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Through compiling the entire year’s reports of cemetery vandalism, it is possible to identify some patterns in criminology, reporting, and recovery. So, prepare to get your headstones toppled, this is 2016 in cemetery vandalism. The Psychology of Vandalism Psychological and sociological theories regarding the motivation of vandalism offenders describe the “typical” vandal as a white male, aged 14 to 20, with a background in petty crime.[2] For these offenders, vandalism can be a means of exerting control on a world in which they feel they have little agency (“equity-control theory”). Other explanations include enjoyment theory, which views vandalism as a source of “flow” for an offender inhabiting an otherwise stifled existence, and aesthetic theory, which simply states that vandals tend to target more complex targets than simple ones.[3] Vandalism in cemeteries tends to add a layer of complexity to psychological theory. The significance of the cemetery in any culture is tangible – the cemetery represents overarching themes of death, remembrance, and identity. When a cemetery is vandalized, it can be perceived as a symbolic attack on death itself, or the entire culture represented by the cemetery. This perception goes both ways – both offenders and victims recognize this meaning. To date, no psychological studies have addressed whether the teenager knocking over markers in his neighborhood cemetery is, on some deep Freudian level, attacking the very concept of death. But perhaps someday such research will be conducted. Politically, Racially, and Religiously Motivated Vandalism The notion that cemeteries represent communities both symbolically and functionally is so often visited that it risks becoming cliché. Yet in no other context is this idea more vital and tragic as in incidents of large-scale vandalism. The cemetery as embodiment of group identity is a global concept. In 2016, international conflicts repeatedly manifested in cemeteries. In Poland, cemeteries of fallen Soviet World War II soldiers were vandalized, representing a clash between historic and contemporary perceptions of the Soviet Union. Baha’i cemeteries in Iran were systemically destroyed. And the ongoing border conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia yielded accusations of cemetery desecration from both sides. Case Study: Derry City Cemetery In Northern Ireland, cemetery vandalism, regardless of motivation, is associated with socio-political sectarianism. Between 2015 and 2016, City Cemetery in Derry/Londonderry was vandalized at least five times, including an arson event. Simultaneously reported as a crime of adolescent perniciousness and motivated by lingering sectarianism, these incidents tie in to the erection of a paramilitary monument in the same cemetery. In nearby Belfast, the vandalism of a Jewish cemetery was viewed as much as an iteration of loyalist/unionist strife as it was an act of anti-Semitism. Derry City Cemetery did not install surveillance cameras until the fifth reported vandalism incident in two years. Presently, the cemetery seeks the draw of tourism as prevention of vandalism, citing the approach taken by Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. While Glasnevin may have mitigated incidents of antisocial behavior in this manner, the comprehensive management of Glasnevin Cemetery only partially relies on tourism. The cemetery clearly benefits from intensive public and private investment. In this light, Derry City Cemetery has more in common with Dublin’s Goldenbridge Cemetery, which was vandalized three times in 2014-2016. In the United States Politically, racially, and religiously-motivated vandalism is no stranger to cemeteries in the United States, either. In 2016, amidst national discussions regarding Confederate monuments in public spaces and in the wake of the murders at the Emanual A.M.E. Church in Charleston, Oakwood Cemetery in Raleigh, North Carolina experienced a large-scale vandalism event. In this case, the “well researched” anti-racist graffiti tagged the graves of Confederate and Lost Cause figures. The Raleigh incident was the only reported instance of anti-Confederate vandalism in cemeteries. However, racially-motivated attacks on African American cemeteries took place more commonly in 2016. In June, the African-American section of Greenwood Union Cemetery in Rye, New York was stripped of its Memorial Day flags. In August, a Wagoner County, Oklahoma cemetery was vandalized with racial slurs. In this case, a passerby noticed the graffiti and covered it with sheets before notifying the police. Many more cemetery vandalism incidents occurred at African American cemeteries but were determined not to be hate crimes. Anti-Semitic Vandalism The perception of the cemetery as manifestation of cultural identity is especially pertinent in the case of Jewish cemeteries. Cemeteries, along with places of worship, are symbolic of the community itself and are targeted by anti-Semitic vandals in a nearly pathological manner. Anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism is something to which New Orleans itself is quite familiar: Hebrew Rest Cemetery in Gentilly and Dispersed of Judah Cemetery on Canal street were vandalized with anti-Semitic and Nazi slurs repeatedly in the 1960s.[4] In 2016, three Jewish cemeteries in the United States were subject to this type of hate crime. Within one week in February, Zion Hill and Dreyfus Lodge Cemeteries were both targeted, resulting in forty total headstones toppled. The Hartford, Connecticut incidents were both investigated by police as hate crimes. Although no report suggests a culprit was identified, Dreyfus Lodge Cemetery restored the damage and held a rededication ceremony after repairs. Beth Shalom Cemetery in Warwick, New York, was attacked with anti-Semitic graffiti in October 2016. The exterior wall of the cemetery was marked with swastikas and “SS” insignia, days before its congregation observed Yom Kippur. The historic and systemic use of cemetery vandalism to intimidate and attack Jewish communities was clearly recognized by members of Temple Beth Shalom. In an interview with local Times Herald-Record, Rabbi Rebecca Shinder stated the vandalism “represents hatred and persecution of the Jewish people throughout the centuries. It’s a symbol of hatred and intimidation.” Days after the incident at Warwick, hundreds of community members arrived at Beth Shalom Cemetery to help remove the graffiti. Incidents of anti-Semitic cemetery vandalism were also reported this year in the United Kingdom and Germany. Many other incidents likely occurred but were not reported, or were not pursued as hate crimes. There is a frequently-used and oft-misattributed quote among cemetery people, to the effect of “Show me a civilization’s cemeteries and I will show you how civilized they actually are.[5]” The quote is usually utilized when discussing the cost of funerals or the frequency of maintenance. But it has an alternate relevance in the sphere of criminology – political vandalism, hate crimes, and other identity-targeted cemetery crime is itself a barometer for larger socio-political trends. Show someone a graffitied 9/11 memorial, a broken police memorial, or a defaced Jewish cemetery, and they will see the evidence of something much larger. Adolescent Vandalism: Joyriding, Robo-tripping, and Satanism Identity-based cemetery vandalism is extremely serious and too often falls between cracks. Yet the vast majority (90%) of the 127 specific vandalism incidents in the United States in 2016 were untargeted incidents involving toppled stones, graffiti, and joyriding. In these untargeted instances, 18% resulted in the arrest or identification of an offender, usually within one week of the incident itself. Identified offenders were typically juveniles – mostly boys but frequently girls. Adults were apprehended for more complex crimes than stone-toppling. In Hickory, North Carolina, a municipal cemetery was collateral damage as a 47 year-old man under the influence of alcohol attempted to evade police by cutting through the graveyard, mowing over 20 headstones in the process before crashing into a veterans’ memorial flagpole. In Douglas, Arizona, a 53 year-old man was caught in the act of stealing more than 70 brass memorial plaques which he intended to sell at a scrapyard.

“Kid”-associated vandalism also seems to bring with it a deliberate “shock” value. In Tennessee and Arizona, cemeteries were tagged with “satanic” graffiti – pentagrams, “666” and other insignia associated with the occult. In the case of San Xavier del Bac Mission cemetery in Arizona, the local Satanic church was contacted for comment and repudiated the act as something unassociated with their group. It should also be noted that this behavior is not restricted to juveniles: a 56 year-old man in Yorkshire, England was arrested in June 2016 for spray painting a cemetery with similar markings.

Some observations of the 184 reports of cemetery vandalism in 2016 offer these suggestive do’s and don’ts: DON’T:

DO:

Preventing and Recovering from Vandalism Most cemeteries, and especially historic ones, are managed by companies or groups with extremely meager funds. Even cemeteries with considerable endowments often operate with high overhead and little left over after basic maintenance costs. Cemetery vandalism is costly to reverse. The cheapest way to recover from cemetery vandalism is to prevent it. If there ever was a “spike” in cemetery vandalism, it happened in the 1960s, coinciding shifts by cemetery authorities to remove full-time staffing from their properties. Full-time staffing permits cemeteries to control the landscape in a way no other management practice can. Secondly, documentation of any cemetery’s current condition is of utmost importance if vandalism is to be identified in the future. Regular photographs of any property (taken either by the property owner or the cemetery authority) are invaluable in controlling vandalism. Maps, measured drawings, and databases are the armor that can protect a cemetery from tens of thousands of dollars in damage. When cemetery vandalism occurs, it must be reported to local law enforcement. Most law enforcement agencies are unaware that cemetery vandalism is an issue. While filing a police report may not produce an arrest, it does produce an important record for the cemetery authority and (where applicable) insurance responses.[6] When the time comes to make repairs, don’t hurry at the expense of quality. Cemetery preservation is a professional discipline populated by experts who have studied methods and materials for years. Sparing expense to make repairs can result in damage that is much more harmful to markers and headstones than the vandalism may have caused in the first place. Proper repairs can facilitate insurance claims, as well. Direct public interest. Take control of the cemetery’s story. Public interest in the preservation of any cemetery is important even before vandalism occurs. After it takes place, enjoining the cooperation of the public can spell the difference between success and failure. It can even prevent vandalism from taking place again. Many cemetery authorities invite volunteers, hold fundraisers, and fun events that introduce the potential vandal to a welcoming, important place. The fifteen year-old that comes to your cemetery movie night might even be the one who stops his friends from tipping a headstone in years to come.[7] Cemetery vandalism is a cultural occurrence which will never be entirely eradicated. But it can be better understood and studied. That way, in 2017, perhaps prevention may be more robust and recovery swifter. [1] Based on 184 news reports from January 2016 to December 2016, only some of which reported the exact number of markers effected and an exact estimation of repair costs. As many instances of cemetery vandalism are never reported, and most costs are not reported, it is reasonable to assume these statistics are much greater.

[2] Arnold P. Goldstein, The Psychology of Vandalism (New York: Plenum Press, 1996), 24. [3] Ibid. [4] Emile Lafourcade, “Vandals Strike Jewish Graves: Headstones are Painted with Swastikas,” Times Picayune, July 2, 1967, 1; “Cemetery Vandalism,” Times Picayune, January 21, 1967, 10 (this incident also involved swastikas); “Vandals Paint Gravestones: Hit Dispersed of Judah Cemetery,” Times Picayune, October 27, 1965, 22 (also swastikas). [5] Other variations: “Show me the cemeteries of a country, and I will tell you of its culture, its civilization” (attributed to Tallyrand), “Show me your cemeteries and I will tell you what I think of your people,” (attributed to Benjamin Franklin), and “Show me the manner in which a nation cares for its dead and I will measure with mathematical exactness the tender mercies of its people, their respect for the laws of the land and their loyalty to high ideals” (attributed to Sir William Gladstone). [6] John Eck, “Preventing Theft and Vandalism in Cemeteries,” Annual Conference of the Association for Gravestone Studies, Salem, OR, 2013. [7] Kuri Gill, “Preventing Vandalism,” Annual Conference of the Association for Gravestone Studies, Salem, OR, 2013.

7 Comments

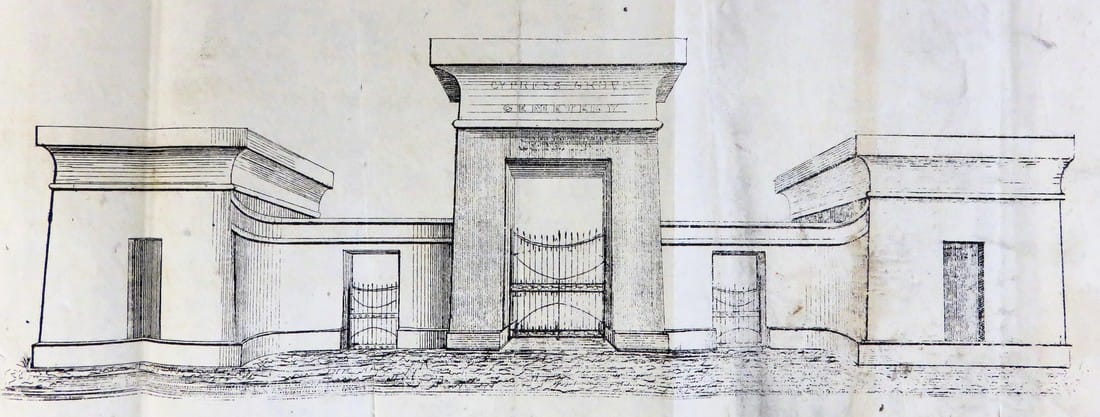

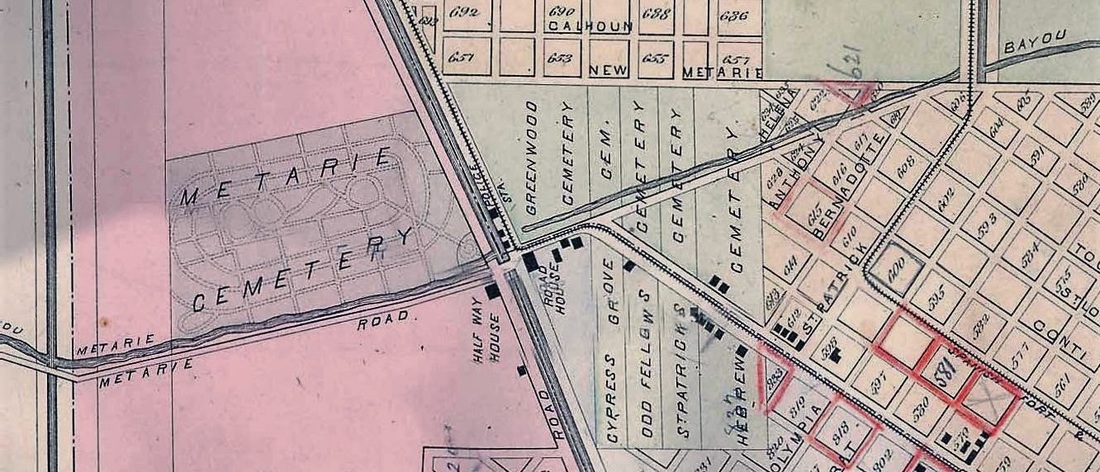

Part Two of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. Find Part One here. In the 1840s, Cypress Grove Cemetery developed into the landscape its founders envisioned: tree-lined and populated with tombs of the finest order. It also gained company as St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest were all established between 1840 and 1850. There at the corner at what is now Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Cypress Grove was part of a pastoral scene: barges floating up Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal, visitors strolling the gardens at the Halfway House, and rail cars pulling up right to the cemetery gates, unloading mourners and the bodies of the mourned.[1] Between its founding in 1840 and the turn of the century, Cypress Grove would become the final resting place of many famous and infamous New Orleans characters. Northern-born transplants to the city would combine New Orleans tomb architecture with the styles and materials they were accustomed to. Firemen would memorialize their fallen brethren within the cemetery’s marble-clad walls. Much of the incremental detail of the cemetery at its height, though, has weathered away from its present-day appearance. It’s easy to miss this historic garden cemetery for its modern lack of trees. But with historic research and a keen eye, it’s possible to rediscover Cypress Grove’s historic grandeur. Firemen, Northerners, and Protestants Cypress Grove was the first fraternal cemetery in New Orleans. All other cemeteries founded up to 1840 belonged either to the Catholic parishes (except Protestant Girod Cemetery, belonging to Christ Church Cathedral) or to each respective municipality (i.e. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1). Many other fraternal organizations, including other firemen’s organizations, would found their own cemeteries over the course of the nineteenth century. Cypress Grove was not intended for the exclusive burial of firemen. It served all New Orleanians seeking burial, if they could purchase a plot, and many who could not. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (present-day Canal Boulevard) was contracted by the City of New Orleans for indigent burial, even after Charity Hospital Cemetery was established in 1848.[2] While Catholics in New Orleans had many cemeteries from which to choose, Protestants had only Girod Street Cemetery and the municipal cemeteries. Perhaps it was simple economics that caused so many Northern-born Protestants to buy property in Cypress Grove. It may also have been caused by cultural interaction between the Firemen (many of whom were also non-native New Orleanians) and others who joined them as newcomers in the Crescent City. In any case, the great majority of historic burials in Cypress Grove denote birth in northern climes such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and others. The Firemen’s Charitable Association fell into this market easily. Stonecutters whose work featured mostly in Girod Street Cemetery, such as long-time Girod Street sexton Horace Gateley, executed tombs and tablets in Cypress Grove as well. Gately himself, who drowned in at Isla del Padre, Texas in 1867, is buried in adjoining Greenwood Cemetery. The FCA even advertised in-ground burial in Cypress Grove. While in-ground burial occurred in nearly every cemetery in the city, FCA was the only cemetery owning body to advertise it – plainly appealing to newcomers with a distaste for Continental-inspired above-ground tombs.[3] When Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957, Cypress Grove became a de facto artifact of what the Protestant cemetery may have looked like. Simpler, sarcophagus-style tombs with accents placed more on great obelisks and sculpture than on Greek acroteria or Baroque scrollwork dotted the aisles of both Girod and Cypress Grove. What few photos of Girod Street Cemetery remain even suggest a few duplicate tombs between both cemeteries: including the now headless and armless tomb statue and tomb of Henrietta Sidle Davidson (died 1881) and another tomb in Girod Street. Philadelphia brick, New Hampshire granite, and other Anglo-inspired tastes contributed to the budding landscape of Cypress Grove.

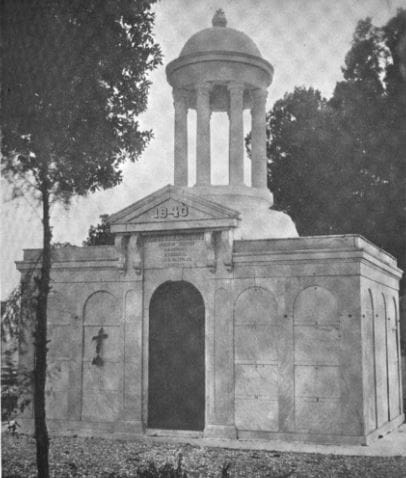

Mr. [S.T.] Jones placed a closely sealed bottle in the box, containing the constitution and list of members of this efflisient [sic] company, the daily newspapers of the city, and the various coins of the country. This was also embedded in mortar, the cover put on, and the whole covered with solid masonry, upon which the corner stone was laid. The beauty of the day, the solemnity of the occasion, and the mournful memories engendered by the scenes around, all contributed to give the ceremony a peculiar interest.[5] The tomb of Perseverance Lodge No. 13 dominated the entrance of Cypress Grove Cemetery then as it does now – a large terra cotta cupola with ionic columns and a cast-iron finial at its dome was constructed atop the tomb roof. At the center of its primary façade, an entrance was likely constructed which was enclosed by cast-iron doors. Above this door were marble brackets and a Classical pediment. The tombs of Philadelphia Fire Engine and Eagle Fire Company were tucked into the front corners of the cemetery. Each built identically, with marble-clad masonry and large urns and finials, they were each enclosed with iron gates, each within the line-of-sight of the Irad Ferry monument. Masterpieces in Marble and Granite Other societies in addition to fire companies would build their tombs in Cypress Grove, most notably the Chinese tomb and Baker’s Benevolent Association tomb. But Cypress Grove would make its mark in the number of great family tombs that populated its aisles. The sarcophagus tomb is one of the most notable artifacts of funerary architecture in New Orleans cemeteries, and in Cypress Grove this was no different. Built of brick and clad in marble pilasters, cornicework, and sculptural elements, the sarcophagus tombs of the McIlhenny, Davidson, Johnston and Walker tombs are examples of the dozens of this burial type found in Cypress Grove. Built by stonecutters like Anthony Barret, James Reynolds, and Newton Richards, they represented the English-speaking stonecutter’s take on a burial style often associated with Creole artisans. The French-speakers were present in Cypress Grove, as well. Sarcophagus tombs by signed by Florville Foy are present beside the work of New Orleans-born Jewish stonecutter Edwin I. Kursheedt. Renowned French-born cemetery architect J.N.B. de Pouilly designed two of the best-known tombs in Cypress Grove: those of Maunsel White and Irad Ferry (constructed by Monsseaux and Richards, respectively).

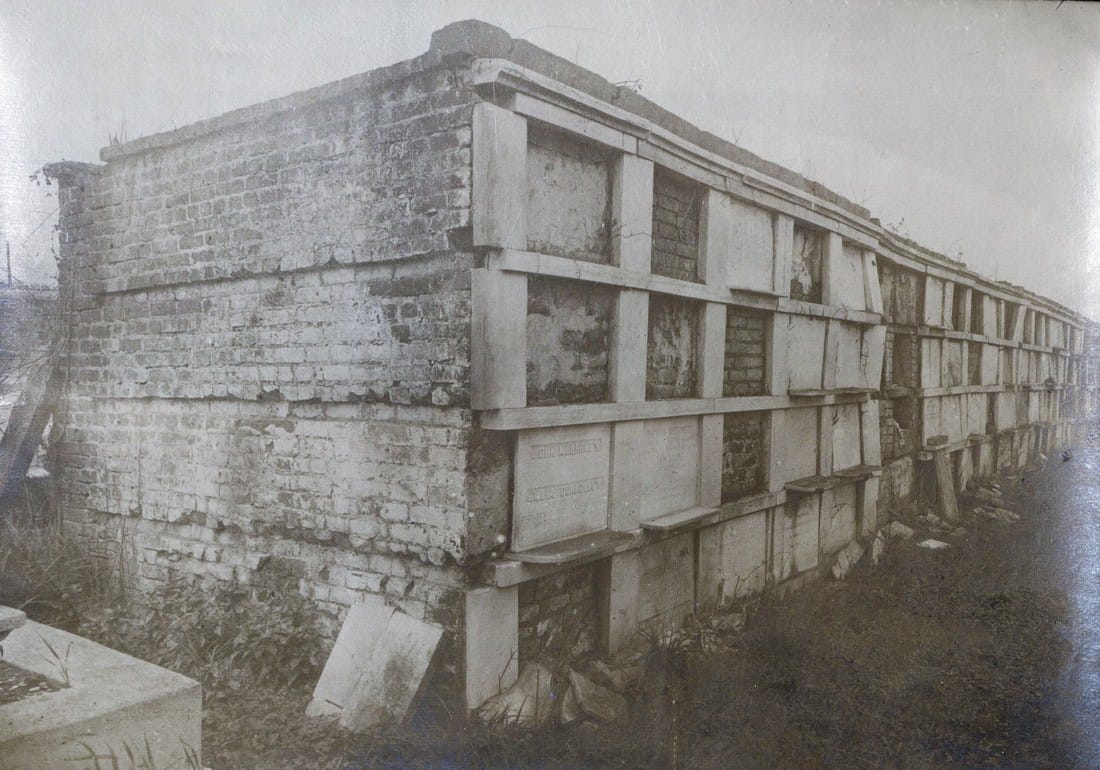

The only remaining example of this style of historic tomb construction lies not in Cypress Grove but in Metairie Cemetery – the Duverje family tomb, constructed between 1808 and 1820 and moved from the family cemetery in Algiers in 1916, retains such acroteria. They are the last of their kind in New Orleans cemeteries. Then and Now After 1945, New Orleans cemeteries underwent a seismic shift in management, industry, and trade. The monument industry had been slowly becoming a national affair managed by large companies – a shift that reached New Orleans after World War II. Over the years, most cemeteries abandoned the employ of the cemetery sexton who traditionally cared for the grounds on a daily basis. Stonecutters, who had often served as sextons, adapted and became cemetery owners and dealers of nationalized products. Technology changed the way tombs were built, repaired, and maintained. This shift affected every cemetery in New Orleans. In the Catholic cemeteries, it led to the consolidation of parish burial grounds into the incorporated New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. In municipal cemeteries, it meant a transfer of management to overstretched city departments that cared for publicly-owned buildings and parks.[7] In the fraternal cemeteries, it meant a consolidation of duties and a new focus on sellable space to accommodate budget shortfalls.[8] With population movement to the suburbs and elsewhere, tombs were less likely to be cared for by their owners. With no sexton to manage the landscape, small issues with tombs became larger problems, often solved in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Storms like Camille, Betsy, and Katrina flooded Cypress Grove Cemetery, killing many of the surviving trees. Those who entered the monument trade after 1950 were much more familiar with new technologies than old materials. Old problems, then, were solved in new ways. In the 1960s, when the marble facing of the extensive wall vaults at Cypress Grove began to sag away from their brick substrate, the decision was made to remove the marble instead of repair it. When landscaping tumuli was too labor intensive, the sod was stripped from their structures, leaving cement-patched, igloo-like bodies behind. Herbicides like RoundUp were selected to replace arduous mowing, damaging masonry and causing grassy root structures to erode, leaving deep ruts which can destabilize walls and tombs. Alternately, trees which lent such a rural feel to Cypress Grove eventually overgrew their root structures, tipping walls and capsizing tombs. All the while, the responsibility of families to care for and repair their own cemetery property became anachronistic in an era of new innovations and perpetual care. The cultural forces that created Cypress Grove had transformed, with the role of the fraternal society somewhat supplanted by the rise of Social Security and insurance companies; the rural cemetery now firmly at the edges of the metropolis. New Orleans cemeteries in general are prized for their historic value, but the value of their maintenance and preservation may exceed that interest from many sides. Yet Cypress Grove remains, its Egyptian columns rising above Canal Street and City Park, where once the bayou and the railroad met. It may be difficult to see it, but with a conscientious eye and a little history, its lost landscapes can be found. [1] “Passenger and Freight Barges on the New Canal,” Daily Picayune, January 1, 1846, 4; Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louis Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Press, 2004), 30-35; At least one duel also took place in front of Cypress Grove’s gates, between former state senator Waggaman and a former New Orleans mayor Prieur, Daily Picayune, March 11, 1843, 2.

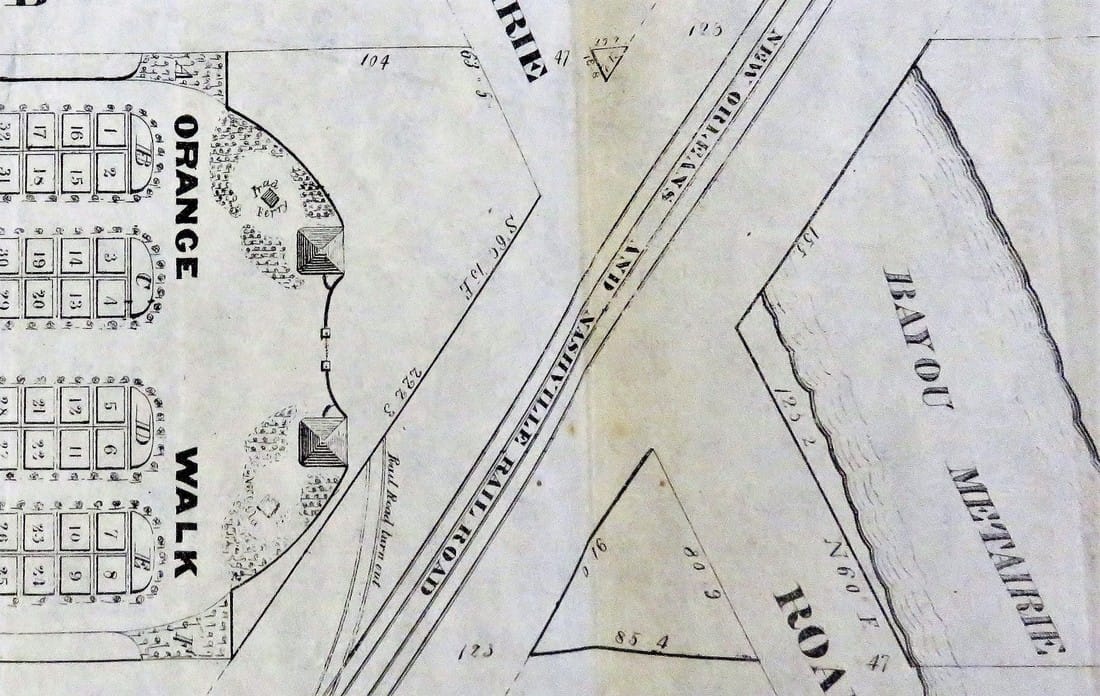

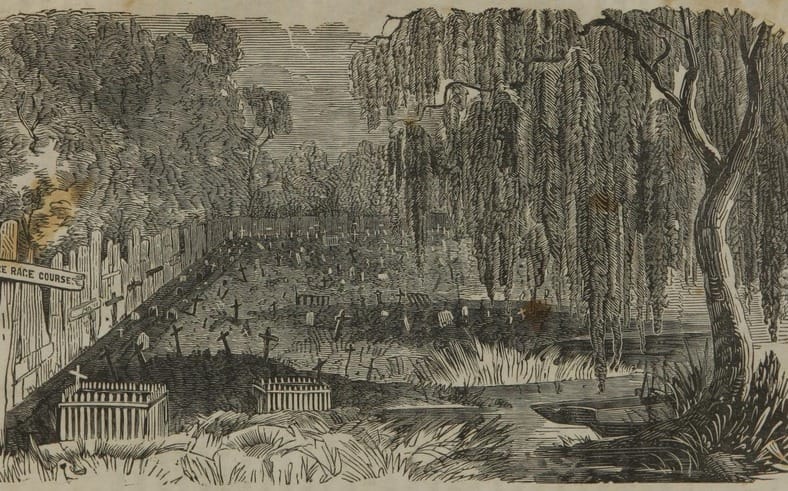

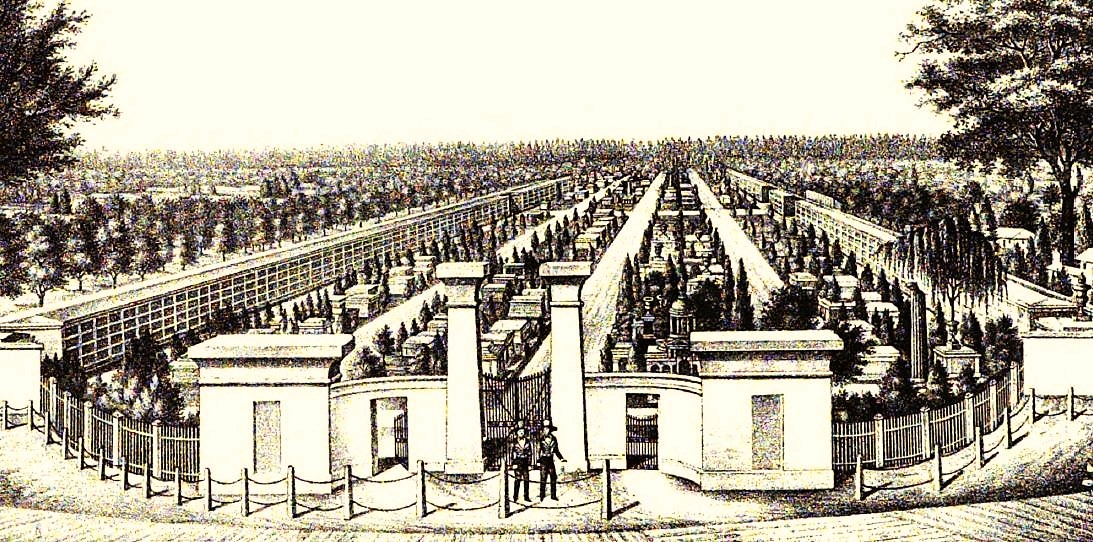

[2] Daily Picayune, April 21, 1846, 2. [3] “Cypress Grove Cemetery,” Daily Picayune, September 15, 1842, 2. Full text: “CYPRESS GROVE CEMETERY. A portion of this rural cemetery having been appropriated for interments in GRAVES, application can be made at the Firemen’s Insurance Office; to M.C. Quirk & Sons, or Mr. Monroe, Undertakers. The Superintendent will also receive at the ground any corpse for interment, on payment of $5 for grown persons and $3 for children. GEORGE BEDFORD, President F.C.A.” [4] “Grand Fancy Dress Ball,” Daily Picayune, February 26, 1852, 3; “Fireman’s Funeral,” Daily Picayune, August 14, 1847, 2. [5] “The City: An Interesting Ceremony,” Daily Picayune, January 3, 1854, 1. [6] Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1855 (New Orleans: Printed at the office of the Picayune, 66 Camp Street, 1855), xiv. [7] Pie Dufour, “Old Cemetery Getting New Look,” Times-Picayune, November 10, 1968. [8] In Cypress Grove, sexton and stonecutter Leonard Gately was instrumental in developing sections into sellable space. Daily Picayune, April 12, 1959, 154. Part One of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. The foot of Canal Street at City Park Avenue is surrounded by cemeteries. At one end, the bronze statue of the Elks Lodge tumulus presides over ever-bustling traffic - right now, in December, the Elk has been decorated with a festive red nose. Facing the intersection from another side is the tall edifice of Odd Fellows Rest. The entrance gate of Cypress Grove stands out even in the grandiose company of these monuments. Comprised of two gatehouses and towering Egyptian Revival pillars, the gate has stood longer than the Elk, the Odd Fellows, or any other cemetery in the area. Within these gates is the oldest rural cemetery in New Orleans. Cypress Grove’s significance is self-evident – its wide avenues showcase example after example of high funeral architecture, of stories that strike the heart of the New Orleans history. But there’s another story among the thousands of tombs in the cemetery. It’s the story of a landscape now obscured by time, of what it used to mean to walk through these aisles. Beyond the mowed grass and paved paths is evidence of what once was a lush, tree-lined landscape on par with the garden cemeteries of the northeast. If you look hard, you can still find it there. The Firemen’s Cemetery Cypress Grove was founded in 1840 by the Firemen’s Charitable Association (FCA), now known as the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association (FCBA). The Association was organized in 1834, about five years after the first New Orleans volunteer fire companies formed. Originally, the Association served in a manner similar to other mutual aid societies: providing social and financial support to the city’s volunteer firemen. Within its first decades, however, the Association became the fire department itself. Until the city switched to a paid fire department in 1892, the Association was responsible for all firefighters in New Orleans – and all firefighters were volunteers.[1] The tale of the founding of Cypress Grove is one well-known to cemetery lovers in New Orleans. On New Year’s Day 1837 while carrying out his duty with Mississippi Fire Company No. 2, thirty-five year-old Irad Ferry perished in a fire on Camp Street. Dubbed the “the first martyr” of the newly-formed fire department, Ferry was venerated with a public funeral and a large memorial march. He was originally laid to rest in Girod Street Cemetery. Along with relief services for their members, benevolent societies of this time provided burial benefits to their members. The Firemen’s Charitable Association was no different, and considered purchasing a section of Girod Street Cemetery for that purpose with plans for Ferry’s monument to be built at its center. But in 1838 the death of Destrehan plantation owner Stephen Henderson widened the Association's prospects. In addition to multiple provisions regarding people enslaved by Henderson, the will specified large bequeaths to religious and social charities, and $500 per annum to the Firemen’s Charitable Association.[2] On Sunday, April 25, 1840, a nearly one thousand firemen, clergy, and prominent citizens marched through downtown New Orleans, each wearing mourning bands and a few carrying urns representing the ashes of their martyred comrades. At Canal Street, they boarded train cars and traveled to Cypress Grove Cemetery, where they re-interred the remains of Irad Ferry beneath a great monument designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and constructed by stonecutter Newton Richards. In a nearby tomb constructed for this purpose, the remains of eleven additional firemen were buried.[3] The Rural Cemetery At its founding in 1840, Cypress Grove became the sixth active cemetery in New Orleans, and the only cemetery at the lake-side foot of Canal Street.[4] Its predecessors were decidedly urban in design: dense, utilitarian though beautiful, and without significant landscaping. A possible exception to this rule was Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, located in what would become the Garden District. Lafayette No. 1 has been referred to as a “transition” cemetery between urban and rural model cemeteries. But even this cemetery was squeezed into a single city block, with no room for the rolling greenery that had become popular in American cemetery design by 1840.[5] Cypress Grove was destined to become something different. Enormous in land area by contemporary New Orleans standards, it was conceived by relative newcomers to the New Orleans Francophile aesthetic. Members of the FCA were often northern-born – for example, Irad Ferry was from Connecticut – and thus influenced by English sensibilities. The Americans brought with them new ideas for cemeteries. They were inspired by what they saw at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and many more. These were cemeteries that were designed instead of planned, with undulating pathways that strolled past weeping willows and reflecting pools. This was the rural cemetery movement, a great shift in the history of cemeteries that would change the American perception of death forever. The rural cemetery movement arose in the northeastern United States as a result of the expansion of cities. Advances in industrialization within the urban landscape created in city-dwellers a longing for the countryside. Furthermore, this same industrialization advanced the American middle class in such a way that recreation was newly defined. Inspired by English landscape design, the rural cemetery was the predecessor to the public park – in fact, Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed one such cemetery in California. This shift in the appearance and purpose of cemeteries coincided with many American cultural movements like Romanticism and the “beautification of death period.” The Firemen’s Charitable Association was certainly aware of this trend. In addition to the explicit use of the term “rural cemetery” in FCA planning documents, the Association expressed a disdain for contrasting urban cemeteries: It would seem almost superfluous to set for the advantages of this rural cemetery. The rapid growth of our city has already encroached upon the tombs of its fathers, and the sacred relics of the dead have been compelled to give way to the cold and selfish policy of speculators, and the intrusion of business; and the solemnity of the grave yard is disturbed by discordant shouts of merriment, and the baleful proximity of the dissolute.[6] If there was any question as to whether the FCA was directly influenced by the rural cemetery movement, one must note that the iconic Cypress Grove entrance gate is a near-exact facsimile of the gate at Mount Auburn. The Cemetery at the Half-Way House For those in FCA who wished Cypress Grove to be a truly rural cemetery, a better location could not have been chosen. The new cemetery was situated at the confluence of vital infrastructure lines: the New Basin Canal and Shell Road, Bayou Metairie, and rail lines at Canal Street. Although the area was an important checkpoint in travel through the area, it was largely undeveloped. One map from 1849 describes the area as a “ridge covered with live oak, persimmon, liriodendron, pecan, wild cherry, interspersed with acacia trees.” The cemetery itself would have, in its own way, water features much like the rural cemeteries it emulated. Early descriptions of the cemetery plan boast “frontage” on both the New Basin Canal and Bayou Metairie. In fact, Cypress Grove Cemetery once straddled Bayou Metairie (today City Park Avenue). The bayou divided Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 1 (present-day Cypress Grove) and Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, a potter’s field now covered by Canal Boulevard. The location of the cemetery not only suited the rural aesthetic but also the new role of the cemetery as a venue for picnics and outings. The Shell Road, which ran alongside the New Basin Canal toward Lake Pontchartrain, was a popular day trip for visitors and locals alike.[7] The Half-Way House and Road House were located at the meeting of the Shell Road and Bayou Metairie – both places of rest, refreshment, and entertainment located at the midway point between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, further cementing Cypress Grove’s destiny as a park-like destination. Growth and Change Those who were drawn to own tombs and lots after 1840 chose Cypress Grove for its bucolic location, wide aisles, and landscaping. In its first twenty years, the cemetery would be filled with some of the grandest architecture New Orleans craftsmen could offer. Its aisles, all named after trees and plants, would bristle with their namesakes shading each pathway. The finest cast iron fences would encircle family tombs clad in marble and Pennsylvania brick. Cypress Grove became, in some ways, an extension of Girod Street Cemetery. Protestants and other non-Catholics sought property within its walls, bringing their taste in obelisks and urns with them. Cypress Grove became home to the second tomb for traditional Chinese burials in New Orleans. The Slark and Letchford families built two tombs inspired by stately Gothic spires along the cemetery’s marble-clad side wall vaults. Cypress Grove would not be alone at the confluence of bayou, canal, and railroad for long. In the same year Cypress Grove was founded, St. Patrick’s Cemetery No. 1 was established. Cypress Grove would be joined by Greenwood Cemetery, Odd Fellows Rest, Dispersed of Judah and other Jewish cemeteries, Charity Hospital Cemetery (now Katrina Memorial), and Masonic Cemetery No. 1. In 1872, Metairie Racetrack would be converted to Metairie Cemetery, and Cypress Grove would be supplanted as the great rural cemetery of New Orleans. One hundred seventy-five years after Cypress Grove’s dedication, there are twelve cemeteries clustered near the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The New Basin Canal was filled in the 1960s and replaced by the Pontchartrain Expressway. Metairie Bayou has been filled and City Park Avenue widened atop it. The Half-Way House and other former New Basin Canal structures were demolished in recent decades. Today, the New Orleans Emergency Communication District buildings are located at the site. Cypress Grove may not be so easily recognized for what it once was. Its trees are mostly missing, replaced by deep ruts in sod where herbicide has taken hold. Many of its great structures have changed or completely disappeared – tumuli stripped of their grassy knolls, wall vaults stripped of their marble facing. Next blog post, we dive deeper into the architectural history of specific tombs and structures in Cypress Grove Cemetery and how they have changed over time. [1] Thomas O’Connor, ed. History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FMBA, 1890), 54-57.

[2] Ibid., 65-70; “Mr. Henderson’s Will,” Daily Picayune, March 17, 1838, 1; Although unrelated to Cypress Grove, the will of Stephen Henderson and how it was executed bears some interest. Among other provisions, Henderson attempted to arrange for the gradual emancipation of his many slaves, with the option for some to be sent to Liberia. Find more here, and here. [3] O’Connor, 70-71. [4] St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, Girod Street Cemetery, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. At least two Potter’s Fields or indigent burial grounds and unknown family cemeteries were also in the City. [5] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 131-145. [6] Firemen’s Charitable Association, Report of the Committee of the Firemen’s Charitable Association, on the Cypress Grove Cemetery (New Orleans: McKean, 1840), 4. [7] Visitor’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: J. Curtis Waldo Southern Publishing & Advertising House, Nov. 1875), 30-33. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly