|

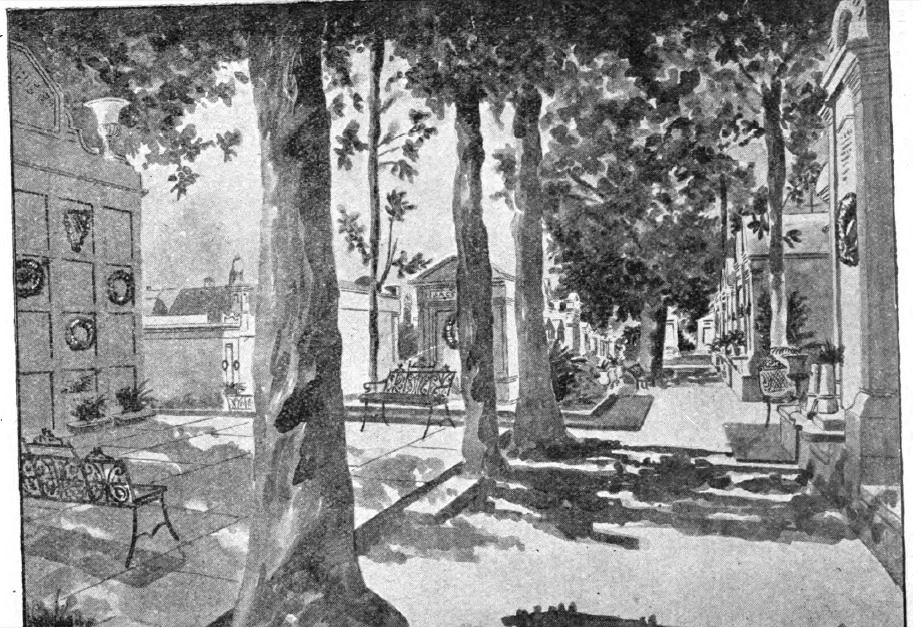

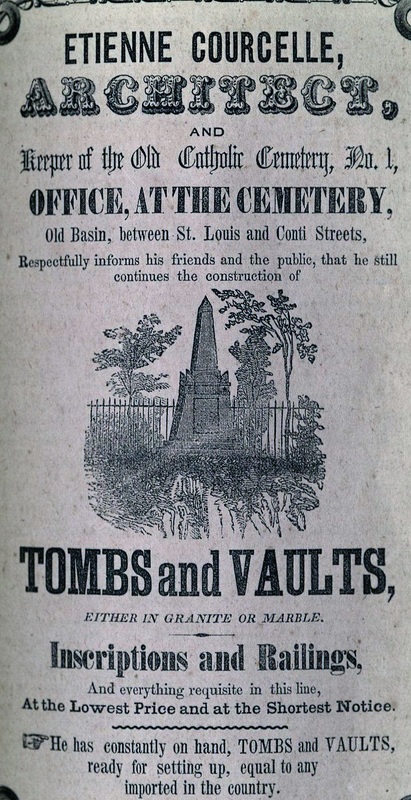

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb.

2 Comments

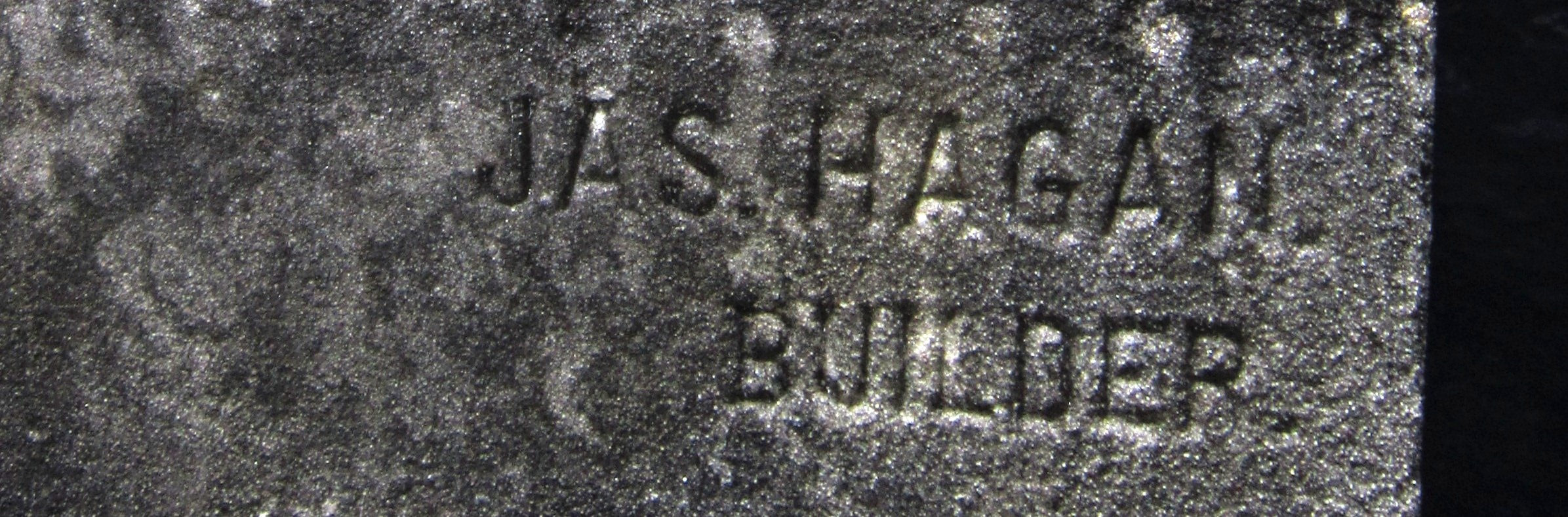

Irish-born Hagan was a state senator, a stonecutter, a real estate developer, and a dock commissioner in his long life, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was deeply shaped by his work. Along the main aisle of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, a pink granite tomb stands out from its lime-washed, marble-clad neighbors. Surrounded by a cast-iron fence, the tomb of James Hagan and John Henderson is often noted as the last resting place of a stonecutter whose work is prominent elsewhere in the cemetery. Yet this note, and the carved name of James Hagan, is only one small detail in the larger story of James Hagan’s life. James Hagan was not only a stonecutter but a real-estate dealer, state senator, community leader, and politician. He lived and worked in New Orleans not only in a time of great social change but a period of high craftwork and architecture in the city’s cemeteries. Among his signed works are some of the most ornate in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, all marked by detailed stonework and expensive marble cladding.[1] Sources suggest that James Hagan built the pink granite tomb not for himself but for his first wife, Mary Henderson, after her death in 1872. Hagan married Mary Henderson in New Orleans shortly after he immigrated from County Armagh or County Antrim, Ireland, in approximately 1852.[2] James Hagan and his brothers John, Peter, and Patrick, as well as their mother, all fled Ireland in the 1850s after famine likely forced them to emigrate. In the Fourth District of New Orleans, formerly the New Orleans suburb of Lafayette, the Hagans joined thousands of other Irish who had formed a community along the banks of the Mississippi River in the neighborhood now known as Irish Channel.

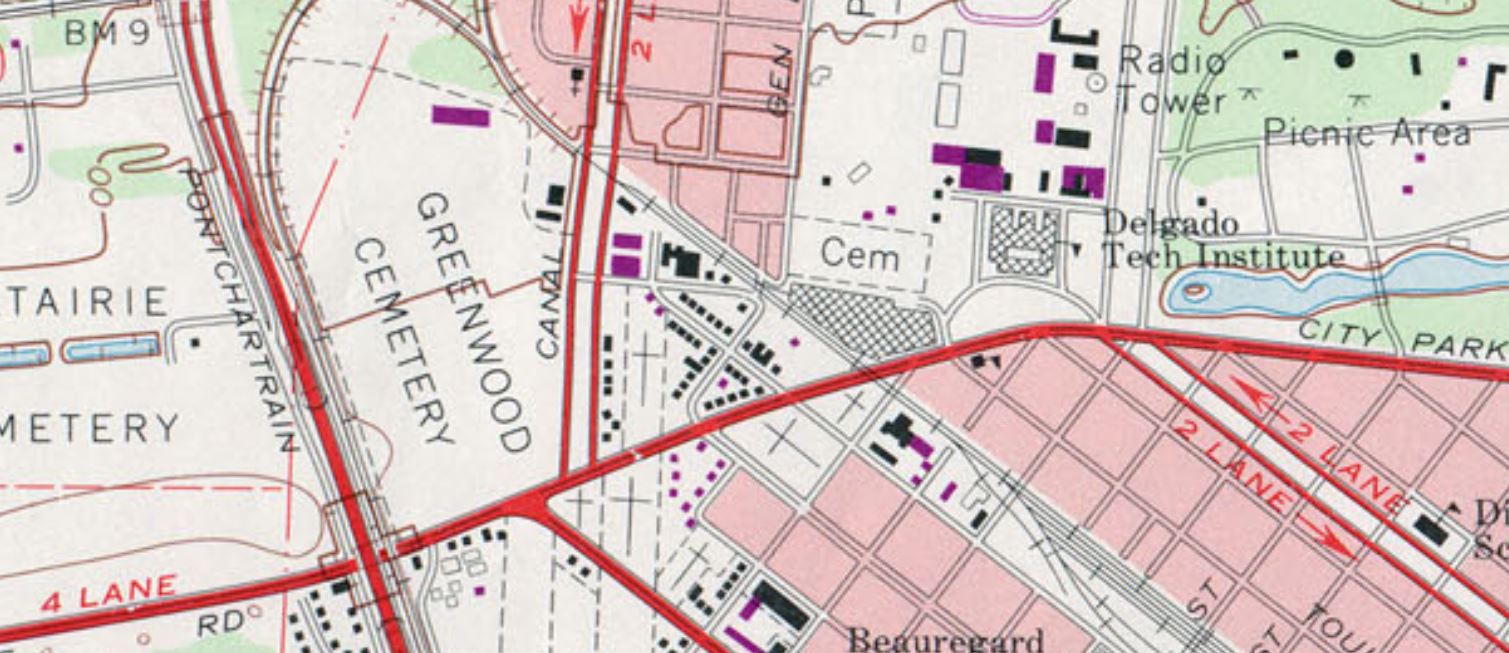

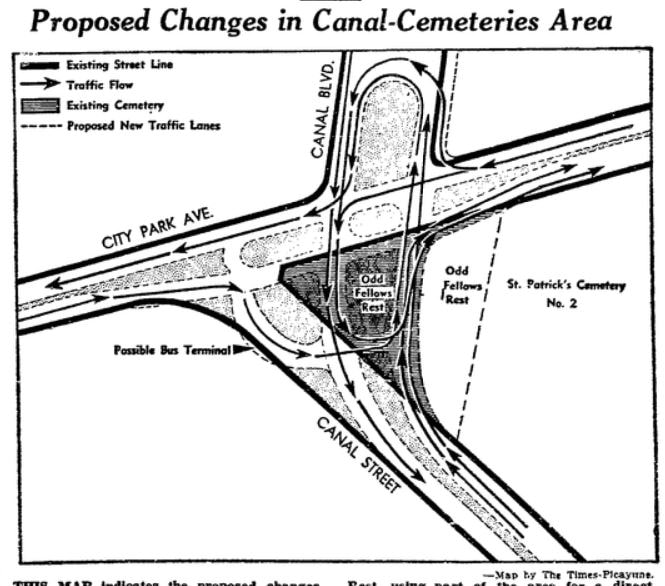

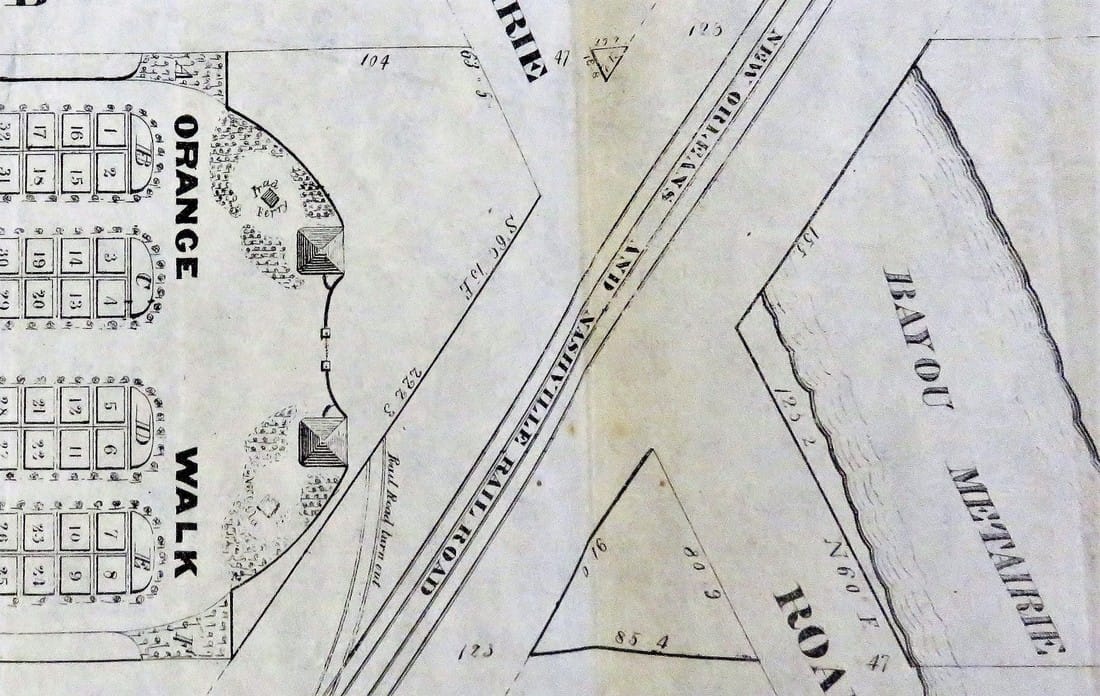

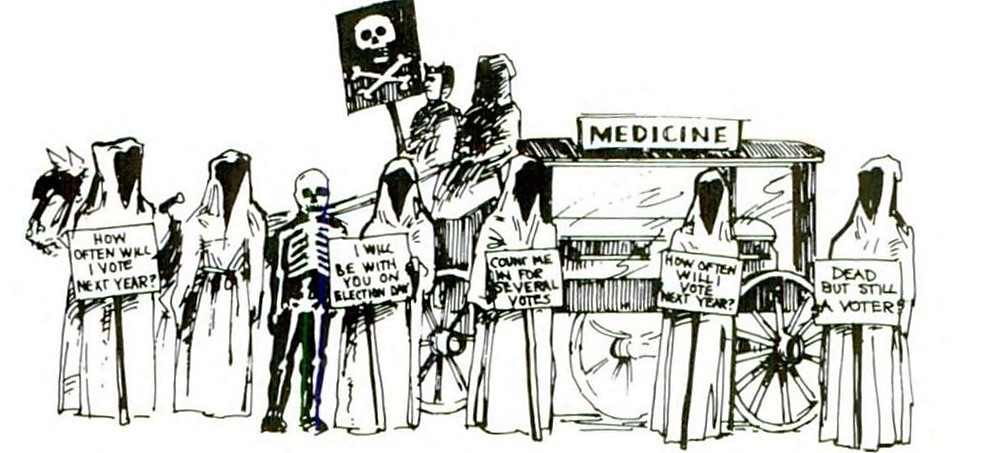

This is the fifth and final part in a five-part series on the historic landscape of City Park Avenue and Canal Street, and its associated cemeteries. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. To start at the beginning of this series, find Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here, and Part Four here. By the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue had undergone a century of extraordinary change. Where once Bayou Metairie meandered westward past acacia trees and a pastoral ridge, now City Park Avenue coasted across the New Basin Canal to become Metairie Road, past the grand monuments of Metairie Cemetery, and into Old Metairie. Where once the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove stood tall over an undeveloped landscape, now cars rumbled past the monuments and walls of Greenwood Cemetery and Odd Fellows Rest. Jazz blared from the Halfway House beside the New Basin Canal through the 1920s, until the House was converted into an ice cream parlor in 1930.[1] Bayou Metairie had slowly been filled in to accommodate City Park Avenue. To the east, Delgado Central Trades School (now Delgado Community College) was opened in 1921. Beside Delgado, Holt Cemetery remained the municipal potter’s field for New Orleans, but in 1940 the cemetery gained a new neighbor – the Higgins Boat Plant. PTs, Higgins, and the Cemetery Andrew Higgins (1886-1952) is known today in New Orleans as the man who brought the shallow-bottom PT and “landing craft, vehicles, personnel” or “LCVP” boats to the Allied effort in World War II. LCVP boats were used extensively in the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1945, leading then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower to say in 1964 that Higgins had “won the war for us.” Before World War II, Higgins had gotten his start designing shallow-bottom boats that performed well in the Louisiana bayous and other waterways beset by submerged obstacles. But by the late 1930s, Higgins produced new designs that not only could achieve amphibious landings in shallow waters, but were also equipped with ramps to allow swift disembarkation upon landing. These qualities made Higgins Boats imperative to the war effort. In 1940, Higgins Industries constructed a $1.5 million boat-building facility in the least expected of places: far from water, along City Park Avenue, and beside Holt Cemetery. Ever known for his enterprising spirit, Higgins’ City Park plant became the “world’s largest boat manufacturing plant housed under one roof.”[1] The plant took advantage of the Southern Railway line that cut northwesterly across City Park Avenue, beside Masonic Cemetery No. 2. Boats would be manufactured at the City Park plant, which employed thousands of people, and shipped to Lake Pontchartrain for testing. The booming wartime production of the plant left the operation bursting at the seams. Said historian Jerry Strahan of Higgins’ need to expand: “The back of the shipyard was adjacent to Holt Cemetery. Higgins decided to enlarge the plant ‘knowingly and willingly’ by preempting an unused portion of the cemetery grounds. The plant was increased until 40 percent of the new facility was constructed on property to which Higgins held no title, a problem that was unresolved as late as 1947.”[2] Photos of the plant and adjoining Holt Cemetery can be found here under photographs numbered 14 and 21. As early as November 1945, the loss of massive wartime governmental contracts hit the Higgins plant hard. The property was put up for sale.[3] The building at 501 City Park Avenue would have myriad uses over the next thirty-five years – it was a Piggly Wiggly grocery store in 1948, offices for Georgia Pacific Corporation in 1959, and part of the building was used as an art warehouse in 1964.[4] From the 1960s through the 1970s, a van and storage company conducted business in the old plant. In 1972, the building was demolished - its walls, beams, floors, and other items sold for salvage.[5] Finally, in 1982, Delgado Community College opened the Arthur J. O’Keefe Administration Building at 501 City Park Avenue.[6] The architecturally intriguing building remains in the same capacity to this day. In 1964, Holt Cemetery would cease to serve as New Orleans’ potter’s field. The city of New Orleans, under coroner Frank Minyard instead leased a lot from Resthaven Cemetery in New Orleans East for this purpose. This section of Resthaven continues to serve as New Orleans’ indigent burial ground. The American Way of Death After the close of World War II, industries which had boomed forward industrially and technologically looked inward for domestic uses of their innovations. Higgins Industries attempted to this very thing: selling Higgins-designed watercraft for private uses. While to contemporary readers it may seem strange, the same phenomenon took place in the funeral and cemetery industries. Moreover, the clientele of these industries had changed: they were more prosperous, more mobile, and had different values. For 1950s Americans, death was to be confronted with more discretion, privacy, and modernity than had been the case for previous generations. The cultural boom of the 1950s held an inherent disdain for the old-fashioned. This trend is often best exemplified in the scorn held for Victorian architecture during this period. Modern Americans sought urban renewal to wipe away old landscapes. In New Orleans, such sentiments manifested in the rapid construction of community mausoleums, establishment of “memorial park” style cemeteries like Garden of Memories, and the destruction of Girod Street Cemetery. Girod Street Cemetery was established in 1822 at the foot of Girod Street near Liberty Street. By the mid-1950s, the cemetery was bounded by the New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, part of a neighborhood seen as old, blighted, and an obstruction to progress. After repeated attempts by the cemetery’s owner, Christ Church Cathedral, to resurrect the cemetery both architecturally and functionally, it was expropriated by eminent domain to the federal government and the City of New Orleans. The cemetery was demolished in 1957. Girod Street Cemetery was located far from the Canal Street cemeteries, but it held certain cultural and architectural ties to other Protestant-dominated cemeteries like Cypress Grove and St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery. As the process of demolition began, the Huber family which had assumed ownership of St. John’s Cemetery in the 1920s, jockeyed for the contract to relocate the Girod Street remains. This competition involved multiple cemetery craftsmen-turned-cemetery owners and would not be the last time a cemetery operator competed for business with his peers. At the same time Girod Street Cemetery was being demolished, cemeteries at Canal Street and City Park Avenue were modernizing. The first inklings of cemetery stoneworkers turning to cemetery operation began in the 1910s and 1920s. For example, in 1910, stonecutter Albert Stewart assumed ownership of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street, acquiring it from the Suarez brothers. The Huber family had gained ownership of St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery in the 1920s – and by the 1930s, began construction on Hope Mausoleum, the first community mausoleum in New Orleans. Community mausoleums had gained some traction in the United States beginning in the 1890s and increasingly so in by the time of the Great Depression. In this era, the idea of a large, single-structure facility for burial appealed to cultural ideals of mutual benevolence (indeed, many belonged to fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows) and frugality. In New Orleans, these cultural desires were often met instead with society tombs – large, multi-vault structures within larger cemeteries. Society tombs were New Orleans’ version of community mausoleums, which reflected a more northern aesthetic. It is, then, not surprising that the Huber family gained ownership of German Lutheran St. John’s Cemetery and erected Hope Mausoleum around the historic burial ground. The development almost appears as an extension of St. John’s, Girod, and Cypress Grove Cemetery’s tendency to reflect non-Francophile aesthetics. In the early 1930s, Hope Mausoleum opened, a modestly Art Deco edifice encased in polished marble and touting itself as, “The Modern Way of Burial.”[8] The postwar boom of the 1950s saw a second heyday for community mausoleums, but these mausoleums suited newer cultural norms. The era valued opulence and modernity, sleek, state-of-the-art materials and a dearth of filigree and detail. The funeral and cemetery industries, rising into a new period of lobbying professional organizations, consolidated costs, and property accumulation, responded in kind. Indeed, author Jessica Mitford in her 1963 indictment of the industry, The American Way of Death, compared the contemporary funeral industry to the car industry of the same age: overloaded with space-age fins and baubles.[9] Thus, the new community mausoleum was meant to be an expression of modernity and opulence, and a doing-away with the stodgy funereal rituals and trappings of the past. Into this new market rose the children of Albert Stewart – Frank Sr. and Charles Stewart. Under their business, Acme Marble and Granite Company, the Stewarts purchased land adjoining the north boundary of Metairie Cemetery and set forth to construct a community mausoleum for the age. Completed in 1958, Lake Lawn Mausoleum would be the “the ultimate in modern burial,” with “paneling of rich mahoganies, carpeted floors, custom-built furniture, and rare plants and flowers.”[1] Lake Lawn would be the anti-Girod Street Cemetery. Historic photos suggest that Lake Lawn advertised within the walls of Girod Street, declaring that burials removed from the old Protestant cemetery could be moved to a thoroughly modern location. In fact, the engineer of Girod Street Cemetery’s demolition, Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, did just that. The contents of the Story family mausoleum, relatives of Mayor Morrison, were moved to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum in May of 1956. In the end, though, Hope Mausoleum would gain the contract to re-inter the white burials from Girod Street Cemetery. In accordance with contemporary segregation laws (even in death) Providence Memorial Park in Metairie would receive the African American burials from Girod Street. The torchbearer of urban renewal, Mayor Chep Morrison, would himself in death become part of the struggle between rising cemetery entrepreneurs, and the clash of new and old New Orleans cemetery culture. Shortly before his death in 1957, entrepreneurial monument man Albert Weiblen, who by this time had expanded his business to owning entire quarries in Georgia, purchased the entirety of Metairie Cemetery. His widow Norma maintained this enterprise after Albert’s passing, and when Mayor Chep Morrison perished in a tragic airplane accident in 1964, a standoff ensued between old Metairie Cemetery and modern, neighboring, Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Mayor Morrison had, as mentioned previously, moved his family’s remains from Girod Street Cemetery to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Yet while the new mausoleum was modern, Metairie Cemetery had been the lauded resting place of New Orleans mayors, governors, and Mardi Gras kings (nine, eleven, and more than fifty, respectively[1]). Metairie’s position in New Orleans culture was to be the hallowed resting place of power in all its forms. Presumably to preserve this reputation, Norma Weiblen called Morrison executor William H. Lindsay, Sr. on May 24, 1964, offering the Morrison family very steep discounts on a new tomb in Metairie Cemetery if they would consider moving Mayor Morrison’s burial there from Lake Lawn Park. She added that Lake Lawn Park was a “stinkpot,” and that she “knew [Metairie Cemetery] was where [Morrison] belonged.”[2] Years later, the matter would result in a lawsuit. Morrison was buried in Metairie Cemetery and, in 1969, Stewart Enteprises purchased Metairie Cemetery, renaming the joined properties “Lake Lawn-Metairie Cemetery.” The modernization of historic cemeteries at the end of Canal Street was fueled by the spirit of an era – and a struggle for space. By the 1950s, many of the cemeteries in the area were more than a century old. Furthermore, the city of New Orleans and the suburb of Metairie had grown tightly around them, leaving no room to expand. Community mausoleums were a practical way to capitalize on sellable space. Metairie Cemetery had made such a venture – filling in one of the cemetery’s lagoons to construct Metairie Mausoleum in 1958. In 1964, the various parish-owned Catholic cemeteries in New Orleans would be consolidated under the new New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. Ten years later, the Calvary at the rear of St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1 would be demolished to construct Calvary Mausoleum. In 1969, the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association would open Greenwood Mausoleum. The Jewish cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would also reorganize ownership. In the late 1950s, the Hebrew Burial Association would form to assume ownership of Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. With religious restrictions against above-ground burial, the cemetery instead appears to have expanded toward Bernadotte Street in this time, where today a section of modern, 1950s granite monuments stands. In 1973, conservative congregation Chevra Thilim established Chevra Thilim Memorial Park in a small triangle of land bounded by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, and Iberville Street. In 1999, Chevra Thilim merged with another congregation to form Shir Chadosh congregation, who retains ownership of the memorial park-style cemetery. Canals, Streetcars, and Automobiles Within cemetery walls, local stonecutters became sales agents and marble increasingly gave way to increased use of granite. No longer the city’s potter’s field, Holt Cemetery became a burial ground for the families of those already interred therein. Outside the cemeteries of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, water and soil gave way to concrete and pylons The New Basin Canal, in service since 1838 and arguably the heart of the cemeteries landscape, was by the 1950s no longer fit for industrial use. As with Bayou Metairie before, the canal was filled in and repurposed for automobile use. In 1958, a new overpass was constructed for City Park Avenue traffic to traverse over the canal, but its use would be short lived. By 1962, sections of the canal nearest to Lake Pontchartrain were filled in and became West End Boulevard. At the end of the wide boulevard’s neutral ground, a civil defense bunker was constructed as a station of command for government in the event of nuclear war. The bunker has been abandoned since the late 1990s, but remains present on West End Boulevard near Robert E. Lee Boulevard. Finally, in 1968, plans that had begun in the 1950s with Mayor Morrison came to fruition and a superhighway was constructed to connect Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Pontchartrain Expressway, part of Interstate 10, was constructed above the filled-in New Basin Canal – replacing high levies and deep water with tall pylons and dipping underpasses. Increased automobile traffic was met with increased automobile infrastructure, but one seemed to continually outpace the other. The roadways as they were in 1968 were complex and disconnected: Canal Boulevard met City Park Avenue, which met Canal Street in a dog-leg which already vexed motorists. The triangular lot of Odd Fellows Rest formed this dog-leg, and in the 1960s, civic eyes turned to eliminate the obstacle. The (sort-of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest As early as 1948, New Orleans’ City Planning Commission recognized the “dog-leg” problem.[13] As automobile drivers increasingly used Canal Boulevard and Canal Street as a commuter route to and from the city, the multiple turns needed to achieve this route caused traffic congestion. While the commission desired nothing more than to connect the two streets, Odd Fellows Rest cemetery had sat firmly between them since 1849. By 1963, the plan to “bypass” Odd Fellows Rest was revived. The Planning Commission announced in August of that year that it sought to purchase “the entire Odd Fellows Rest on the downtown river side of the intersection of Canal st. and City Park ave. and a very small portion of the adjoining St. Patrick No. 2 cemetery.”[14] The City would purchase the cemetery, relocate the remains interred therein, and demolish the remainder in order to connect Canal Street and Canal Boulevard. Like its neighboring cemeteries, Odd Fellows Rest had struggled to transition from the nineteenth century to the postwar era. In 1950, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) hired stonecutter Armand Rodehorst, Sr. as the new superintendant of the cemetery.[15] Rodehorst had worked for fifteen years across the street at Greenwood Cemetery, as a laborer for Samuel Gately. In joining Odd Fellows Rest, he was striking out on his own.[16] Rodehorst developed Odd Fellows much in the same way that other cemeteries had done. He built multi-vault tombs to sell piecemeal and constructed modern, cast-concrete tombs. In 1958, however, Rodehorst died in his home at the age of 56.[17] The economic future of Odd Fellows Rest was left without a helmsman. Thus, by 1963, the Louisiana Grand Lodge was positioned to sell the cemetery property, although “not interested in partial relocation, but in total relocation of the cemetery.”[18] City Council, Mayor Victor Schiro, and the Planning Commission agreed to fund the project. Property on City Park Avenue near Delgado Community College was selected, which the City would purchase and gift to the Odd Fellows for transfer of the cemetery’s remains. City Council purchased a lot “bounded by City Park Avenue, Conti Street, Virginia Street, and St. Louis Street” for the purpose.[19] Yet in a twist of fate perhaps unique to New Orleans and its local politics, a private firm learned of the land purchase and beat the City to the punch. The purchaser, Plaza Towers, Inc., bought the property and, in turn, offered to gift it to the City in exchange for another parcel of municipal land located on Howard Avenue and South Rampart. Unlike the City Park Avenue property, which was purchased only as leverage, the Plaza Towers firm needed the Howard Avenue property in their construction project: the forty-five story Plaza Tower building designed by Leonard R. Spangenberg, Jr. & Associates. This obvious power grab left City Council “irate.”[20]

In August of 2005, flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina effected even the cemeteries of Metairie Ridge. Metairie Cemetery lost its administrative building near the cemetery entrance, and untold tombs were damaged. In 2008, state-owned Charity Hospital Cemetery was converted into a memorial to the lives lost in Hurricane Katrina. The property was excavated and analyzed by archaeologists, and large vaults were erected, clad in reflective black granite. The unidentified and unclaimed remains of 86 hurricane victims were interred at this site, which each year is visited and dedicated on the anniversary of Katrina’s landfall. To learn more about the inspiring, harrowing, and touching story of the Katrina Memorial, please read this fantastic piece by Mary LaCoste in the Louisiana Weekly: “Remembering the Katrina Memorial that Almost Wasn’t.” The Last Days of the Halfway House The Halfway House, once positioned tranquilly along the New Basin Canal but by 2005 instead wedged beside the Interstate 10 overpass, was also damaged in the storm. Beginning in the 1840s as a place of rest and refreshment for carriages en route to Lake Pontchartrain, later a restaurant and jazz hall, then an ice cream parlor, the building was purchased in the 1950s by Orkin Pest Control Company. Abandoned by Orkin in the mid-1990s, by 2005 the property was derelict, its roof partially collapsed. The Halfway House was the property of the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association, held by a long-term lease by the city of New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina, plans were set in motion to convert the adjoining property – once Albert Weiblen’s marble shop – into the new 911 Communications Center for the city. It looked as if the Halfway House would be demolished to make way for a parking lot. Even before 2005, an organization called the Jazz Restoration Society worked with the FCBA and City to secure ownership of the Halfway House, with the goal of restoring it to a restaurant and music hall. Years of infighting, pushing and pulling, and negotiations in the city finally ended in 2009, when the building was declared a landmark and the Society was given permission to step in. But, much like the land deal between the City and Odd Fellows Rest, another shoe had to drop. When an environmental assessment was conducted at the Halfway House, soil tests found that forty years of pesticide storage and disposal left the property unsalvageable by even the best intentions. Despite years of fighting to save the Halfway House, it was demolished in 2010. Conclusion As of this writing, the current road construction project at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is on-schedule and should be finished in one week. Streetcar lines are laid, sweeping across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard. Archaeological assessments and relocation of remains from the cemetery beneath Canal Boulevard have taken place. Soon, the intersection will assume its most recent form, in a place that has held so many forms for one hundred and eighty years. In this series, we have seen this place conform to cultural changes, urban expansion, technological innovation, war, and peace. It is a testament to how imperceptibly dynamic New Orleans cemeteries are – that we can walk through them and feel tranquility and stillness, when in reality they’re shifting, conforming, losing and gaining things that will be held precious by future generations. And there’s even so much we’ve left out! Left out was the Perseverance Lodge No. 13 society tomb in Cypress Grove, hit by lightning twice in the late twentieth century and recently reconstructed by FCBA. Left out was the flower shop on Canal Street beside Cypress Grove, once a hub for chrysanthemums and roses shuttled off to the cemeteries, by the 1990s derelict, and demolished in 2016. The merger of Stewart Enterprises, Inc. with Service Corporation International in 2014 merits its own thousand words on the industrialization of funeral and cemetery industries. Uncountable changes have taken place in this tiny colony of cities of the dead. This retrospect, more than anything, then, has been an overture to recognizing how very important those aspects of our cemeteries which have survived all of this. From Cypress Grove to Chevra Thilim Memorial Park, from Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum to Holt Cemetery, it is impossible to appreciate these relics too much. [1] Samuel Charters, A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 257.

[2] Jerry Strahan, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats that Won World War II (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1994), 49-50. [3] Ibid. [4] “For Sale: Two of the Modern Higgins Industrial Plants and Clinic in New Orleans,” Times-Picayune, November 19, 1945, 17. [5] Times-Picayune, April 11, 19; Times-Picayune, October 6, 1959, 27; Times-Picayune, April 5, 1964, 71; Times-Picayune, February 10, 1964, 45. [6] “Higgins Shipyard,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1972, 44. [7] “Congratulations Delgado,” Times-Picayune, March 4, 1982, 19. [8] “The Modern Way of Burial” was Hope Mausoleum’s official slogan from the 1930s through the 1950s. For example, “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, May 2, 1935, 2; and “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, January 26, 1958, 2. [9] Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 20-21. [10] “Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, October 3, 1954, 15; “Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum – A Report on Progress,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1951, 10. [11] Henri A. Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, Inc., 1981), 108. [12] “Details on Switch of Morrison’s Burial Site Revealed,” Times-Picayune, May 5, 1966. [13] “End to Canal ‘Dog-Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1. I would like to recognize and thank Michael Duplantier for sharing resources and information contained in the (sort of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest section. [14] Ibid. [15] “Odd Fellows Cemetery,” Times-Picayune, December 26, 1950, 41. [16] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1935, Vol. LXI (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1935), 1171; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1938 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1938), 933; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1949 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1949), 1209. [17] “Business, Civic Leader Expires: Rodehorst Rites will be Held Today,” Times-Picayune, September 16, 1958. [18] “Accord on Canal Street ‘Dog Leg’ Plans Possible,” Times-Picayune, November 7, 1963, Section 2, 6; “Lodge to Help on Street Link,” Times-Picayune, August 20, 1963, 7. [19] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [20] “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, June 3, 1964, 1. [21] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [22] Edward J. Branley, New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line (Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 95. Published 144 years ago today in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, an interview with the assistant sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. It’s unclear how much of this article is speculative or fanciful, but in any case its content is fascinating. The article is presented here in pieces, with background inserted regarding the content. Original Times-Picayune narrative from July 13, 1873 is indicated in italics. Sitting on a Tombstone TALK WITH A GRAVEDIGGER --- “How long wil a man lie i’ the earth ere he rot?” [Hamlet] A reporter of the PICAYUNE, chancing in his peregrinations to stroll into the Washington Cemetery[1] in the cool of early morning, met and engaged in conversation with the assistant sexton. The term “sexton” is given to a person who maintains a cemetery in a professional capacity. It originated with a religious connotation, indicating a man who cared for both the church building and the adjoining cemetery. Later, as more and more cemeteries were established outside parish land, the term “sexton” migrated to the secular sphere. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as a municipal cemetery, and thus was never religiously affiliated. In 1873, the sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and 2 was Joseph F. Callico (1828 – 1885). Callico was a free person of color who worked for most of his career beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, and also beside fellow stonecutter Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. Around 1870, when Monsseaux himself ceased his business, Joseph Callico moved to Washington Avenue to serve as the sexton of the Washington Cemeteries. By 1875, he returned to St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, where his brother Fernand served as sexton.[2]

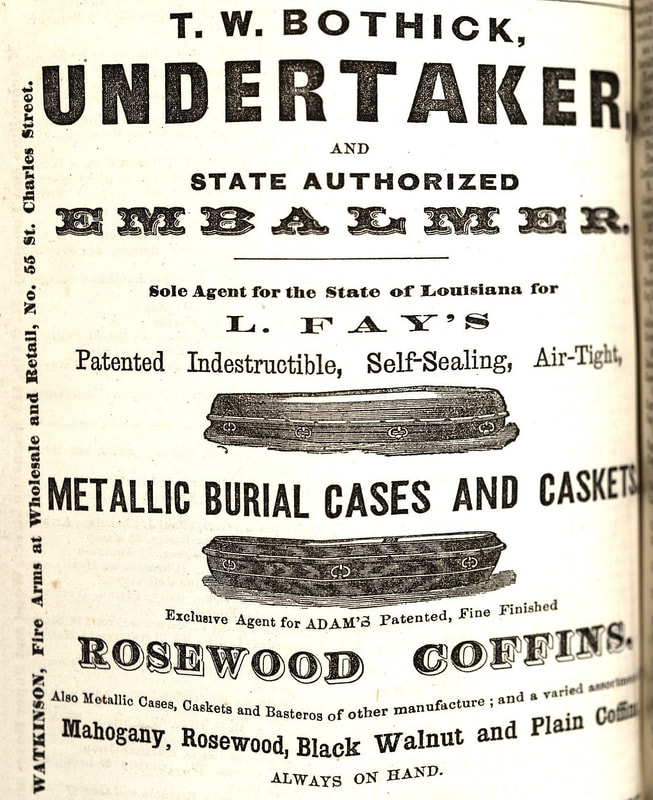

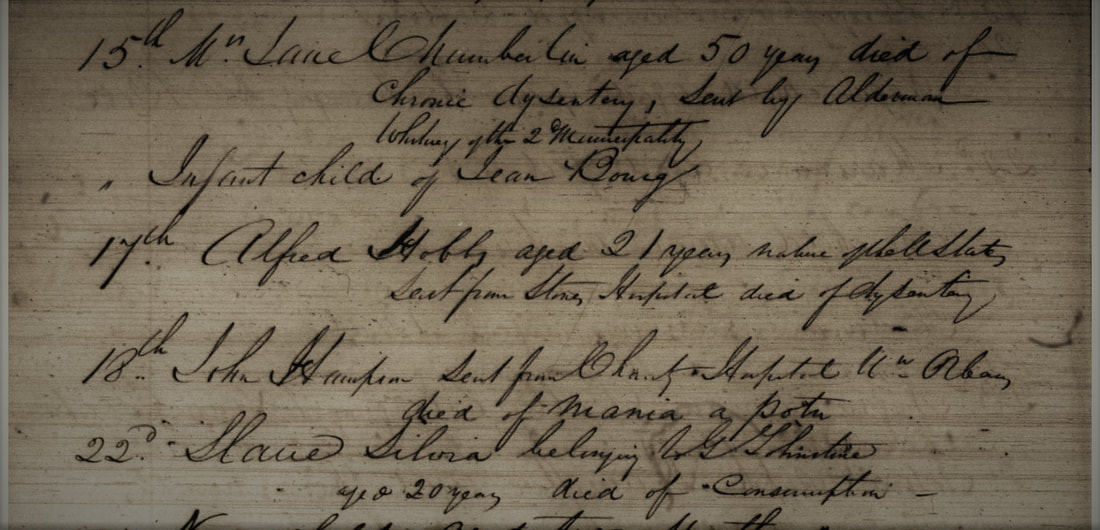

“Well, you know,” said the man, “there is a great difference in them. There are some here who, from their particular situation, keep much longer than others. There’s a man I came across the other day, digging a foundation for a tomb, who had been in the ground for two years, and he was in remarkably good condition. It is true, he was near the wall, and the drainage was good.” This passage offers some confirmation of what the landscape history of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 suggests: that earlier below-ground burials were replaced by above-ground tombs. Dr. Bennett Dowler wrote in 1852 that Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was a primarily a belowground cemetery, owing to the preference of Irish and German immigrants for inhumation over tomb burial.[4] Pre-1850’s burials in Lafayette No. 1 are difficult to find today, but most of which remain show some modification over time, suggesting that the assimilated children and grandchildren of immigrants later converted their family lots to traditional New Orleans tombs. This could be one reason the sexton came upon a burial while constructing a new tomb. The gravedigger expands on this notion in his next answer. “Do they bury many in the ground now in this cemetery?” “No,” said he “in this place most everyone has a tomb. You know, this yard has been buried some ten times over, and people don’t care to put their friends under earth when tombs don’t cost much more.” While “ten times over” may be exaggerated for Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in 1873, the cemetery was declared “full” by Lafayette and New Orleans city councils in 1847 and 1856, respectively.[5] Neither of these ordinances was paid much mind, and burials continued. Furthermore, in the earliest years of the cemetery, between 1833 and 1853, approximately 30% of the individuals listed in interment books are noted as enslaved people. Amounting to thousands if not tens of thousands of burials, records do not indicate their location, although they are unlikely to be in the cemetery wall vaults.[6]  Excerpt of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 interment books for August 1843. Over this week, burials included two deaths from dysentery, a twenty year old enslaved woman who died of consumption, and a death from "mania a potu," an historic term for alcohol-related illness, including delirium tremens. (New Orleans Public Library) From here both gravedigger and journalist get grim: “From your experience, what part of the body is the first to suffer from the effects of decomposition?” “The head goes first always. You see there isn’t so much flesh about it, and it doesn’t take long for it to go. The other parts go after it very soon; they all seem to go together.” While the good taste of asking this question in the first place is suspect, it is interesting to note the anachronism. In 1873, embalming had only recently become a possibility. The widespread practice of embalming starting in the twentieth century certainly affected the decomposition patterns of burials in New Orleans tombs and elsewhere. “In digging about these unoccupied places, do ever meet with the remains of human beings?” asked the reporter. “Oh, yes. The whole of Lafayette Cemetery has been filled, even to the avenues. When this was first a graveyard, it was not laid out regularly, and now when we have to repair the walkways, the bones are always turned up.” Prior to cement paving and other improvements that took place beginning in the 1940s, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1’s aisles were paved with crushed shells, marble pavers, and slate flagstones. Some of these paving materials remain visible. Archaeological test pits executed in the 1980s and 1990s indicated that crushed shells were regularly hauled into the cemetery to repave aisleways. This is likely the “repair to the walkways” the sexton mentions above. [more unnecessary description of decomposition] “Is there any difference between burying in the ovens and in the ground?” “Oh! Yes. In the ovens they don’t last six months, for with the metallic cases it does not take much time to destroy everything. In the ground, metallic cases, if they are good, last twenty years, and wooden ones about three."

"Yes! I have noticed that when they take on most they generally don’t come back to put flowers on the tomb much after the first month. “The widows come every week for about a month or two, fixing up everything. When they cry most they don’t come back at all, but when you see one who looks all the time at the coffin and doesn’t make a fuss you can be sure she will put flowers there for years.”

[1] Historically, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is frequently referred to as “the Washington Cemetery.”

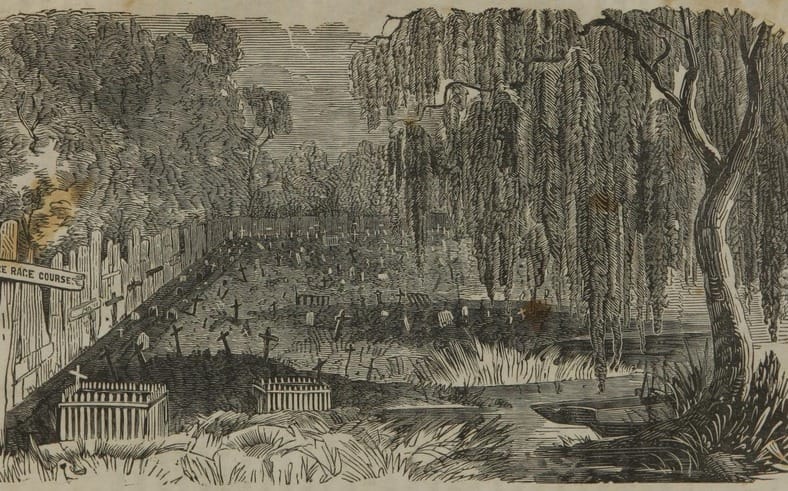

[2] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84, 40; Edwards Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1872), 86; Edwards Annual Directory for New Orleans 1873 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1873), 90; United States Census, 1880, New Orleans, Louisiana, Roll 461, Page 234C. [3] “All Saints’ Day – The Living Remember the Dead,” Times-Picayune, November 2, 1873, 1. [4] Bennet Dowler, M.D., “Tableaux, Geographical, Commercial, Geological and Sanitary of New Orleans,” printed in Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1852 (New Orleans: Office of the Daily Delta, 1852), 21. [5] Mayoralty of New Orleans, Common Council, City of New Orleans, “An Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4. [6] New Orleans Public Library, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Interment Records, Vols. 1-5, microfilm. [7] Dowler, 21. Part Two of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. Find Part One here. In the 1840s, Cypress Grove Cemetery developed into the landscape its founders envisioned: tree-lined and populated with tombs of the finest order. It also gained company as St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest were all established between 1840 and 1850. There at the corner at what is now Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Cypress Grove was part of a pastoral scene: barges floating up Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal, visitors strolling the gardens at the Halfway House, and rail cars pulling up right to the cemetery gates, unloading mourners and the bodies of the mourned.[1] Between its founding in 1840 and the turn of the century, Cypress Grove would become the final resting place of many famous and infamous New Orleans characters. Northern-born transplants to the city would combine New Orleans tomb architecture with the styles and materials they were accustomed to. Firemen would memorialize their fallen brethren within the cemetery’s marble-clad walls. Much of the incremental detail of the cemetery at its height, though, has weathered away from its present-day appearance. It’s easy to miss this historic garden cemetery for its modern lack of trees. But with historic research and a keen eye, it’s possible to rediscover Cypress Grove’s historic grandeur. Firemen, Northerners, and Protestants Cypress Grove was the first fraternal cemetery in New Orleans. All other cemeteries founded up to 1840 belonged either to the Catholic parishes (except Protestant Girod Cemetery, belonging to Christ Church Cathedral) or to each respective municipality (i.e. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1). Many other fraternal organizations, including other firemen’s organizations, would found their own cemeteries over the course of the nineteenth century. Cypress Grove was not intended for the exclusive burial of firemen. It served all New Orleanians seeking burial, if they could purchase a plot, and many who could not. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (present-day Canal Boulevard) was contracted by the City of New Orleans for indigent burial, even after Charity Hospital Cemetery was established in 1848.[2] While Catholics in New Orleans had many cemeteries from which to choose, Protestants had only Girod Street Cemetery and the municipal cemeteries. Perhaps it was simple economics that caused so many Northern-born Protestants to buy property in Cypress Grove. It may also have been caused by cultural interaction between the Firemen (many of whom were also non-native New Orleanians) and others who joined them as newcomers in the Crescent City. In any case, the great majority of historic burials in Cypress Grove denote birth in northern climes such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and others. The Firemen’s Charitable Association fell into this market easily. Stonecutters whose work featured mostly in Girod Street Cemetery, such as long-time Girod Street sexton Horace Gateley, executed tombs and tablets in Cypress Grove as well. Gately himself, who drowned in at Isla del Padre, Texas in 1867, is buried in adjoining Greenwood Cemetery. The FCA even advertised in-ground burial in Cypress Grove. While in-ground burial occurred in nearly every cemetery in the city, FCA was the only cemetery owning body to advertise it – plainly appealing to newcomers with a distaste for Continental-inspired above-ground tombs.[3] When Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957, Cypress Grove became a de facto artifact of what the Protestant cemetery may have looked like. Simpler, sarcophagus-style tombs with accents placed more on great obelisks and sculpture than on Greek acroteria or Baroque scrollwork dotted the aisles of both Girod and Cypress Grove. What few photos of Girod Street Cemetery remain even suggest a few duplicate tombs between both cemeteries: including the now headless and armless tomb statue and tomb of Henrietta Sidle Davidson (died 1881) and another tomb in Girod Street. Philadelphia brick, New Hampshire granite, and other Anglo-inspired tastes contributed to the budding landscape of Cypress Grove.

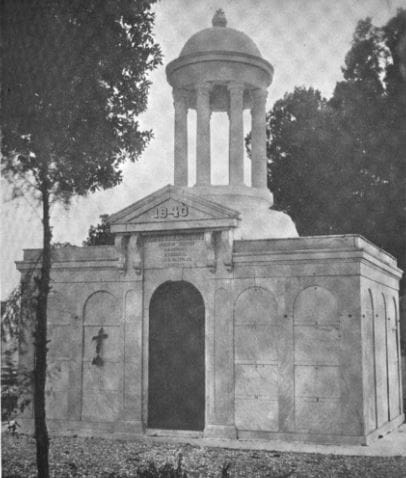

Mr. [S.T.] Jones placed a closely sealed bottle in the box, containing the constitution and list of members of this efflisient [sic] company, the daily newspapers of the city, and the various coins of the country. This was also embedded in mortar, the cover put on, and the whole covered with solid masonry, upon which the corner stone was laid. The beauty of the day, the solemnity of the occasion, and the mournful memories engendered by the scenes around, all contributed to give the ceremony a peculiar interest.[5] The tomb of Perseverance Lodge No. 13 dominated the entrance of Cypress Grove Cemetery then as it does now – a large terra cotta cupola with ionic columns and a cast-iron finial at its dome was constructed atop the tomb roof. At the center of its primary façade, an entrance was likely constructed which was enclosed by cast-iron doors. Above this door were marble brackets and a Classical pediment. The tombs of Philadelphia Fire Engine and Eagle Fire Company were tucked into the front corners of the cemetery. Each built identically, with marble-clad masonry and large urns and finials, they were each enclosed with iron gates, each within the line-of-sight of the Irad Ferry monument. Masterpieces in Marble and Granite Other societies in addition to fire companies would build their tombs in Cypress Grove, most notably the Chinese tomb and Baker’s Benevolent Association tomb. But Cypress Grove would make its mark in the number of great family tombs that populated its aisles. The sarcophagus tomb is one of the most notable artifacts of funerary architecture in New Orleans cemeteries, and in Cypress Grove this was no different. Built of brick and clad in marble pilasters, cornicework, and sculptural elements, the sarcophagus tombs of the McIlhenny, Davidson, Johnston and Walker tombs are examples of the dozens of this burial type found in Cypress Grove. Built by stonecutters like Anthony Barret, James Reynolds, and Newton Richards, they represented the English-speaking stonecutter’s take on a burial style often associated with Creole artisans. The French-speakers were present in Cypress Grove, as well. Sarcophagus tombs by signed by Florville Foy are present beside the work of New Orleans-born Jewish stonecutter Edwin I. Kursheedt. Renowned French-born cemetery architect J.N.B. de Pouilly designed two of the best-known tombs in Cypress Grove: those of Maunsel White and Irad Ferry (constructed by Monsseaux and Richards, respectively).

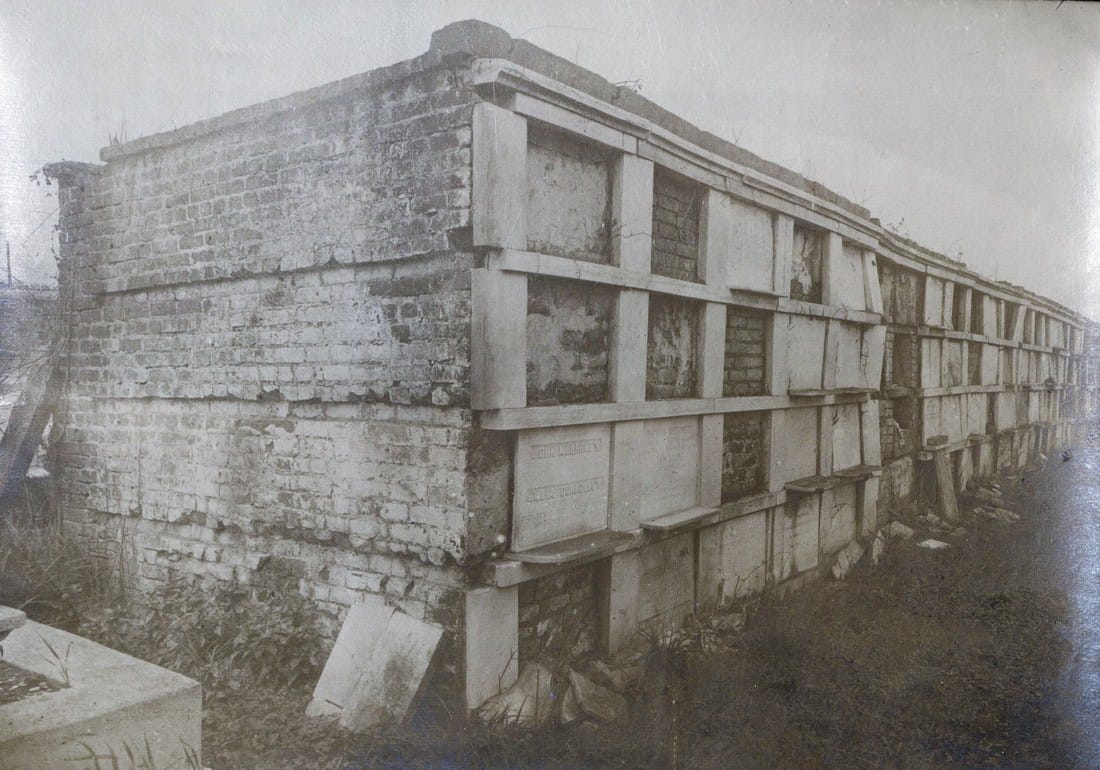

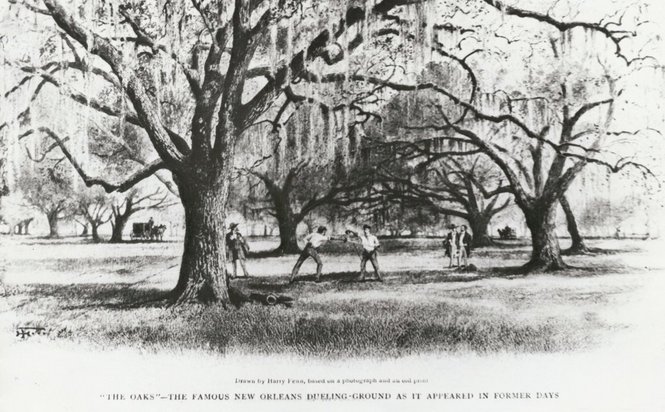

The only remaining example of this style of historic tomb construction lies not in Cypress Grove but in Metairie Cemetery – the Duverje family tomb, constructed between 1808 and 1820 and moved from the family cemetery in Algiers in 1916, retains such acroteria. They are the last of their kind in New Orleans cemeteries. Then and Now After 1945, New Orleans cemeteries underwent a seismic shift in management, industry, and trade. The monument industry had been slowly becoming a national affair managed by large companies – a shift that reached New Orleans after World War II. Over the years, most cemeteries abandoned the employ of the cemetery sexton who traditionally cared for the grounds on a daily basis. Stonecutters, who had often served as sextons, adapted and became cemetery owners and dealers of nationalized products. Technology changed the way tombs were built, repaired, and maintained. This shift affected every cemetery in New Orleans. In the Catholic cemeteries, it led to the consolidation of parish burial grounds into the incorporated New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. In municipal cemeteries, it meant a transfer of management to overstretched city departments that cared for publicly-owned buildings and parks.[7] In the fraternal cemeteries, it meant a consolidation of duties and a new focus on sellable space to accommodate budget shortfalls.[8] With population movement to the suburbs and elsewhere, tombs were less likely to be cared for by their owners. With no sexton to manage the landscape, small issues with tombs became larger problems, often solved in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Storms like Camille, Betsy, and Katrina flooded Cypress Grove Cemetery, killing many of the surviving trees. Those who entered the monument trade after 1950 were much more familiar with new technologies than old materials. Old problems, then, were solved in new ways. In the 1960s, when the marble facing of the extensive wall vaults at Cypress Grove began to sag away from their brick substrate, the decision was made to remove the marble instead of repair it. When landscaping tumuli was too labor intensive, the sod was stripped from their structures, leaving cement-patched, igloo-like bodies behind. Herbicides like RoundUp were selected to replace arduous mowing, damaging masonry and causing grassy root structures to erode, leaving deep ruts which can destabilize walls and tombs. Alternately, trees which lent such a rural feel to Cypress Grove eventually overgrew their root structures, tipping walls and capsizing tombs. All the while, the responsibility of families to care for and repair their own cemetery property became anachronistic in an era of new innovations and perpetual care. The cultural forces that created Cypress Grove had transformed, with the role of the fraternal society somewhat supplanted by the rise of Social Security and insurance companies; the rural cemetery now firmly at the edges of the metropolis. New Orleans cemeteries in general are prized for their historic value, but the value of their maintenance and preservation may exceed that interest from many sides. Yet Cypress Grove remains, its Egyptian columns rising above Canal Street and City Park, where once the bayou and the railroad met. It may be difficult to see it, but with a conscientious eye and a little history, its lost landscapes can be found. [1] “Passenger and Freight Barges on the New Canal,” Daily Picayune, January 1, 1846, 4; Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louis Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Press, 2004), 30-35; At least one duel also took place in front of Cypress Grove’s gates, between former state senator Waggaman and a former New Orleans mayor Prieur, Daily Picayune, March 11, 1843, 2.

[2] Daily Picayune, April 21, 1846, 2. [3] “Cypress Grove Cemetery,” Daily Picayune, September 15, 1842, 2. Full text: “CYPRESS GROVE CEMETERY. A portion of this rural cemetery having been appropriated for interments in GRAVES, application can be made at the Firemen’s Insurance Office; to M.C. Quirk & Sons, or Mr. Monroe, Undertakers. The Superintendent will also receive at the ground any corpse for interment, on payment of $5 for grown persons and $3 for children. GEORGE BEDFORD, President F.C.A.” [4] “Grand Fancy Dress Ball,” Daily Picayune, February 26, 1852, 3; “Fireman’s Funeral,” Daily Picayune, August 14, 1847, 2. [5] “The City: An Interesting Ceremony,” Daily Picayune, January 3, 1854, 1. [6] Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1855 (New Orleans: Printed at the office of the Picayune, 66 Camp Street, 1855), xiv. [7] Pie Dufour, “Old Cemetery Getting New Look,” Times-Picayune, November 10, 1968. [8] In Cypress Grove, sexton and stonecutter Leonard Gately was instrumental in developing sections into sellable space. Daily Picayune, April 12, 1959, 154. To call any cemetery landscape “eclectic” is usually an understatement. Within cemetery landscapes are the architectural whims of uncountable individuals, families, and craftsmen. And so it goes that in New Orleans cemeteries we pass a Gothic chapel and find a Celtic cross. Our landscapes are amalgams of recollection – Classical Greek, Roman, and Egyptian are at home with the Italianate, the Moorish Revival, and the Art Nouveau. This rich tradition has inspired architects to look backward for inspiration, but there is no farther backward one can reach than the tumulus. Known also as a barrow, the tumulus is a burial structure that rises from the ground as a hill or mound. Often, the tumulus bears a means of access from the side or top of the hill. Its origins span across the ancient world, both Old and New, representing a common type of burial shared between the ancient Norse, Etruscans, Chinese, Native Americans, and many, many more.[1] This type of burial also has its home in New Orleans cemeteries. The Elks Lodge tumulus in Greenwood Cemetery, and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia in Metairie Cemetery are often used as examples for the tumulus in modern cemeteries. Yet they are not alone in their unique appearance. The tumulus once graced many more New Orleans cemetery landscapes than it does today. In this blog post, we explore the origins, proliferation, and eventual disappearance of the tumulus in New Orleans cemeteries. Mounds, Barrows, and Antiquarians In Europe, mound, barrow, or tumulus burial was practiced by pre-Roman and Roman cultures. Tumuli can be found in nearly every European country – today as protected archaeological sites and heritage attractions.[2] The practice of mound burial was abandoned after the rise of Christianity and the development of churchyards in Europe. Until the cemetery landscape was reinvented by the rural cemetery movement in the early 19th century, the tumulus was a thing of ancient history. A number of factors contributed to the reintroduction of the tumulus to cemetery landscapes in Europe and the New World. With the establishment of cemeteries like Pere Lachaise in Paris, the understanding of cemetery landscapes shifted into one of green space and architectural eclecticism. From this cultural development sprang the Greek Revival architecture that proliferated New Orleans thanks in part to J.N.B. de Pouilly. But the gaze of nineteenth century Europeans and Americans did not exclusively look back to Greece. It turned to Egypt and the Middle East. It incorporated Gothic spires into new designs. And it looked even farther back to the mysterious mounds found in the European countryside. By the 1870s, the antiquaries of Europe excavated numerous tumuli in England, Italy, France, and Norway. Such discoveries were commonly featured in New Orleans newspapers.[3] An awareness of the burial mounds of great ancient cultures joined Greek temples and Gothic cathedrals in the consciousness of New Orleaneans. Furthermore, the people of the American South were familiar with mound burial in their own backyards. The presence of seemingly abandoned mounds in the southern and mid-western United States had captured the interest of Europeans since Hernando de Soto reported their existence in 1541. After colonization and into the nineteenth century, some of these mounds in Louisiana were repurposed by Americans for use as their own cemeteries. This was the case in Monroe’s Filhiol-Watkins Cemetery. Fleming Plantation Cemetery is also located on a Native American mound. By the mid-nineteenth century, mound burial was firmly rooted in the imagination of New Orleaneans. From these inspirations, the tumulus made its debut in cemetery landscapes. The Tumulus in New Orleans Like the city itself, New Orleans cemeteries are the product of many layers of community and identity. Each cemetery is a reflection of the people who made it their own. Cemeteries that were built and utilized by Irish, German, or American New Orleaneans developed with a different aesthetic than those shaped by French speakers. Each community drew upon their own culture and style to create their cemetery. The tumulus entered the popular consciousness in part via a new interest in archaeology and ancient architecture.[4] Though tumuli in New Orleans often had Greek Revival motifs, they were utilized by Americans elsewhere in the United States. Great northern cemeteries like Mount Auburn featured tumuli as part of their cultivated agrarian landscapes, as did closer cemeteries in Charleston and Savannah.[5] Thus, it is no surprise that tumuli in New Orleans appeared first in American and not Francophone cemeteries – decades before the Elks, the Army of Tennessee, or the Army of Northern Virginia. Tumuli are found primarily in the Canal Street cemeteries, including Cypress Grove, Masonic, Odd Fellows Rest, and Greenwood. They are also found in American-oriented cemeteries like Lafayette Cemeteries No. 1 and 2. There are dozens of tumuli to be found in our cemeteries, yet the untrained eye will not find one. Hidden Tumuli, or How the Lawnmower Changed Everything Most tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries no longer look like tumuli. Stripped of their grassy hill features, they appear instead simply as unusual tombs with rounded bodies. The Hornor and Holdsworth tumuli in Cypress Grove and Masonic Cemeteries (respectively) are good examples. Both constructed with a marble primary façade featuring relief carvings of cut flowers, they were likely carved by the same craftsperson, although neither structure is signed. Both tumuli have conspicuously rounded structures that seem to contrast with the grandiose style of their primary face. Yet when imagined as they originally appeared, as green hills from which their marble faces projected, their aesthetic comes together. There are many former tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries that have been stripped of their signature mounds. The John P. Richardson tomb, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, was described in 1885 as “enclosed in a tall oval mound of turf, with marble doors set in a stone frame.”[6] The tumulus memorialized Richardson’s young daughters – Ella and Marguerite Callaway or “Calla,” ages six months and four years old. This original appearance could certainly not be deduced from examining the Richardson tomb today: its sweeping marble doors and arched primary face are attached to what appears to simply be a brick-and-mortar tomb. Dozens of former tumuli can be found in New Orleans cemeteries; most are identified by the slightly unusual appearance of the tomb body when compared to its front. Nineteenth century tumuli were designed to appear monumental in both mass and detail, with their entrances featuring sweeping side elements or rounded tops. The massive hill that comprised the tumulus body framed these features. Other examples of former tumuli include:  McIntosh tumulus, Cypress Grove Cemetery. In November 1873, the Nixon (now McIntosh) tomb was described as: "in the form of a mound overgrown with grass, with a large marble front. Along the top of the slab creeps an ivy, which will eventually cover the whole mound. The frontispiece was garnished on each side by a vase of white flowers." (New Orleans Republican) The disappearance of historic tumuli can be explained in the same way many other landscape features have been altered. As cemetery design, economics, and management changed, the tumulus was viewed as far too costly to maintain. Before the 1920s, cemeteries featured cultivated grounds with aisles paved in crushed shells – and they were manicured using manual, spiral-bladed lawn-cutters. Between 1920 and 1945, new lawnmowing equipment was patented with small gas-powered motors, cutting down on the labor required for landscape maintenance. This innovation was later supplemented by the availability of ready-mix concrete with which to pave once shell-strewn aisles. Finally, in the 1940s, industrialization of the monument and funerary industries led to most cemeteries eliminating the position of sexton (caretaker) from their ranks.

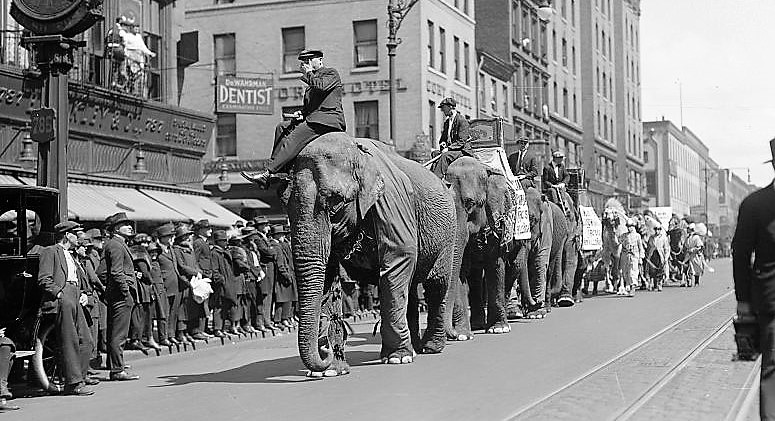

Each tumulus memorializes the fallen Confederate soldiers and deceased veterans associated with each division. After the Civil War, veterans of both Confederate and Union armies formed such benevolent associations for the support of their members. In the case of the Armies of Northern Virginia and Tennessee, perhaps the tumulus design was a nod to the military and fraternal connotations many ancient tumuli bear. Each tumulus features a remarkable sculpture at its hillside apex. The Army of Northern Virginia tumulus supports a 38-foot column atop which a sculpture of General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson stands. The Army of Tennessee features an equestrian bronze, sculpted by Alexander Doyle, depicting General Albert Sidney Johnston atop his horse, Fire Eater. Both tumuli are notable features of Metairie Cemetery, included in most histories of the cemetery.[7] The third notable tumulus in New Orleans is viewed daily by many city commuters. The tomb of the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, Lodge 30, features a bronze elk standing atop its grassy summit. The tumulus is located in Greenwood Cemetery at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, where the elk looks out above the traffic. The Elks lodge tumulus was first conceived of in 1911 by the local Elks, who held a great circus in downtown New Orleans to raise funds for the cause. In subsequent years, the Elks would commission monument man Albert Weiblen to construct the tomb at the cost of $10,000 (approximately $250,000 in 2016 currency). The structure was assembled of Alabama granite, shaped with a classical pediment, the center of which features a clock forever frozen at the eleventh hour, a reference to the “Eleventh Hour Toast” held by Elks when gathered together. Local legend has suggested that Albert Weiblen warned the Elks that the lot on which they wished the tumulus be constructed was not suitable for a structure of that size. It is true that, historically, City Park Avenue was once part of a navigation canal, an infill had only partially stabilized the soft earth. The story goes that the Elks decried Weiblen’s warning and enjoined he move ahead with construction. While primary sources for this story are nonexistent, the Elks Lodge tumulus does have a noticeable tilt toward Canal Street. Lessons in Preservation While the tumulus holds its place of honor in cemetery landscapes with the Elks and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia, it has faded from the everyday view of most cemeteries. Such a loss is difficult to quantify. Historic New Orleans cemeteries are dynamic places where features are constantly altered, modified, destroyed, or restored. Yet as we approach the task of preserving these cemeteries as functional landscapes, the tumulus offer some distinct lessons. Stripped-down tumuli confuse the historic appearance of cemeteries like Cypress Grove and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Had these structures been preserved, their green mounds would carry on the tradition of the cemetery as garden space; and they would properly communicate the historic landscape for both grieving family and heritage tourist alike. Stripped-down tumuli are an example of one cardinal rule of cemetery preservation: that once improper treatment has taken place, it’s nearly impossible to reverse. Each blow to responsible and considerate preservation is most likely permanent. Thus, while restoration is important, maintenance, documentation, and planned preservation are much more crucial. When the cemetery landscape is understood and preserved, large-scale restorations are less necessary. Finally, stripped-down tumuli teach us to deeply consider each structure as part of a whole, to read the structure for what isn’t there as much as for what is. Through this consideration, cemetery stewards can preserve these resources of history and heritage in a responsible manner that benefits generations to come. [1] Dan Hicks, et. al. Envisioning Landscape: Situations and Standpoints in Archaeology and Heritage (Routledge, 2016), 167.

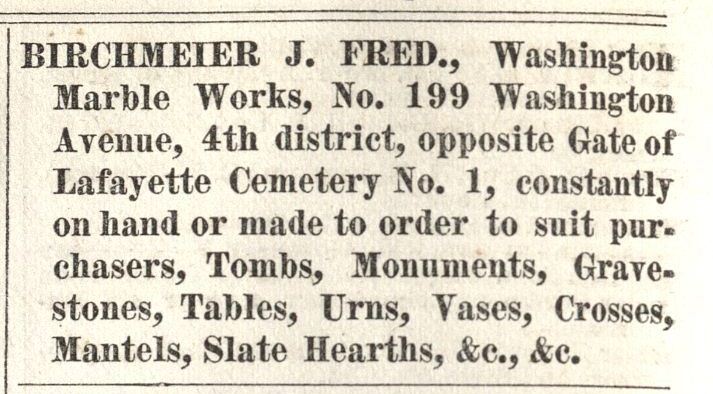

[2] James C. Southall, The Recent Origin of Man (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1875), 87-97. [3] “Jackson Mounds,” Daily Crescent, January 16, 1851; “Norwegian tumulus,” New Orleans Bulletin, April 8, 1874, 2; “Norwegian Tumulus,” Opelousas Journal, August 4, 1876, 1. [4] George F. Beyer, “The Mounds of Louisiana,” in Publications of the Louisiana Historical Society (New Orleans: 1895), 12-30. (Link) [5] Gibbes tumulus, Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, SC, and HABS documentation (Library of Congress). [6] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1885, p. 2. [7] Henri Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery, An Historical Memoir: Tales of its statesmen, soldiers, and great families (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, 1981). Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. Full text here: http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/ The history of sextonship in New Orleans is as old as the city’s cemeteries. The origin of the cemetery sexton derived from European tradition, in which the sexton would care not only for the graveyard surrounding a church sanctuary, but also for the church itself. In New Orleans, the first sextons likely were part of a lay ministry, employed by the Catholic Church to care for St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and, later Saint Louis No. 2. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, however, was not administered by the Church or any other religious group. Instead, it was established in 1833 by the municipality of Lafayette, a suburb of New Orleans. Translating from the ecclesiastical to the secular sphere, the City of Lafayette employed a sexton to care for the cemetery at Washington Avenue and Prytania Street. From the cemetery’s founding into the 1950s, at least twenty-two individuals served as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Many were stonecutters and tomb builders, some were additionally undertakers, politicians, and masons. They cared for the cemetery in times of epidemic, vandalism, and population shifts. Through their stewardship, the landscape of the cemetery was formed. Phil Harty and the First Sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Up to and after the City of Lafayette was incorporated into the City of New Orleans in 1852, the role of the sexton was to perform and record interments, submit interment records to the city council, and maintain the cemetery grounds. It was also his responsibility to enforce the ordinances of the city and state regarding interments and sanitary conditions.[1] These laws included the collection of a certificate of burial (presented by a physician or coroner to the deceased’s family), ensuring the deceased was properly placed in a coffin, and construction regulations regarding tombs. Failure to perform these duties resulted in punishment from City Council.[2] Sextons were additionally paid a fee for each interment based on the deceased’s status as colored or white, child or adult, and whether the interment was to be an act of charity. In the nineteenth century, these fees varied from 50 cents to $1.50, with a $3.00 charge for the opening and closing of tombs and vaults, to be paid by the owner.[3] The first sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was most likely B.S. Quinman, who served from 1832 to 1844.[4] After Quinman, H.G. Hicks served briefly in the position. While many sextons constructed tombs in Lafayette No. 1, no structure or tablet in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 bears either man’s signature. Their successor, however, seems to have made more of an impact on the cemetery. Philip Harty, mostly referred to in documentation as Phil Harty, served as Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 sexton from 1855 to 1861. [5] Only one of his signed works survive amidst the rows and aisles of tombs: the tomb of A. Thomas, located near the rear gate.[6] He lived at 197 Washington Street, across from the main gate of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. This address was utilized by numerous sextons and stonecutters throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Today, the lot is listed as 1427 Washington Avenue. The building is currently utilized as the administrative offices for Commander’s Palace restaurant. Phil Harty died August 14, 1861. His obituary, describing his death as “sudden,” states that Harty was well-known as a sexton and a “hearty, merry fellow up to the very hour of his death. Thousands he has introduced to the narrow house, and now he has gone himself, with scarcely a moment’s warning.”[7] D.F. Simpson, a local stonecutter, followed Harty as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1863 to 1868. He was also a stonecutter and tomb builder – his office was located on Race Street.[8] Examples of his work remain in the cemetery today, including the Stearns tomb and at least three constructed while Simpson was in business with later sexton J. Frederick Birchmeier. Following D.F. Simpson were James Hagan (1830-1908, sexton 1865-1867), and Joseph F. Callico (sexton 1867-1875).[9] James Hagan served as state senator representing Orleans Parish from 1880 to 1884. Based on remaining signed tombs and closure tablets, J.F. Callico was one of the most prolific stonecutters among the sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1: today, nearly thirty tablets in the cemetery bear his signature. 1865 – 1900: A Thriving Craft Community The late 1870s were unusual for the stewards of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in that no one individual served for more than a few years. As had occurred in previous years, especially 1853, yellow fever epidemics were particularly difficult times for sextons. It is possible, then, that the 1878 epidemic, the marks of which are still very visible on the tombs and tablets of Lafayette No. 1, caused an upset in the administration of the cemetery. In quick succession, Dennis Irvin, Cornelius Donovan, John Barret and Patrick Gallagher served as sextons from 1876 to 1880. Patrick Gallagher likely left his office due to accusations against him that he attempted blackmail on an unnamed person.[10] After these men, J. Frederick Birchmeier, a stonecutter who had been active in Lafayette No. 1 for decades, became sexton.[11]

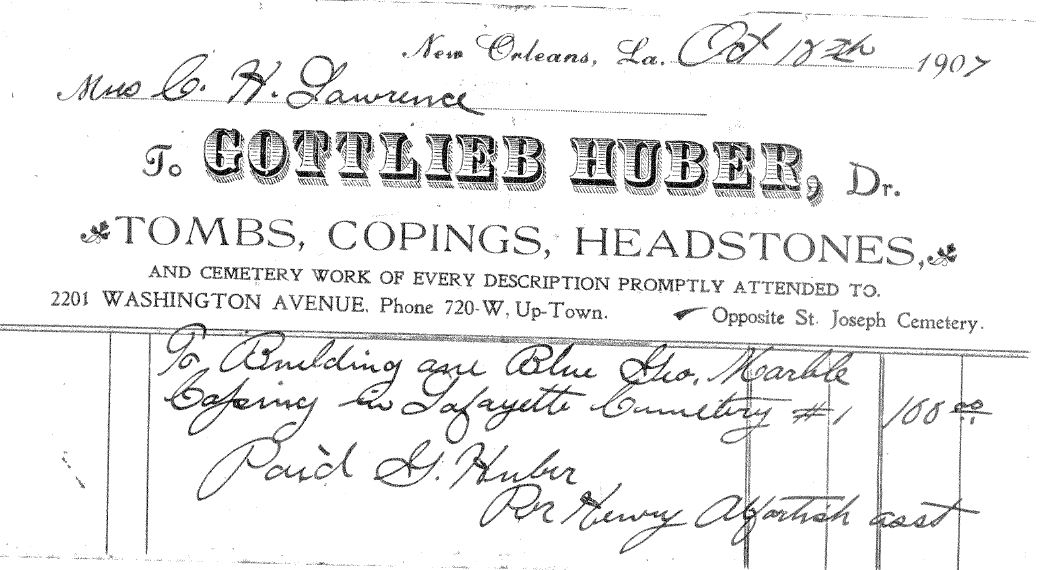

The turn of the twentieth century brought to Lafayette No. 1 a close-knit community of stonecutters and tomb builders, many of whom served as sextons. After J. Frederick Birchmeier retired, his colleague Hugh J. McDonald (1853-1895, sexton 1886-1895) took over stewardship of the cemetery. After McDonald’s death, stonecutter Charles Badger succeeded him. Badger was also the husband of Birchmeier’s daughter, Margaret.[14] Both Badger and McDonald were close colleagues of Gottlieb Huber, who was sexton from 1902 to 1915. The legacy of this community would continue for the next thirty years through another young protégée of these men. 1900 – 1945: The Alfortishes In 1911, Henry Alfortish became assistant to Gottlieb Huber at Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Alfortish also worked with Huber privately, and would absorb Huber’s business after his death in 1926.[15] The influence of Alfortish and, later, his son Edward, would greatly change the cemetery. In the 1920s, Alfortish declared numerous lots abandoned and “open for sale.” He sold these lots and tombs to new clients and, additionally, provided replacement deeds for families who had lost their tomb ownership documents. It was also under the sextonship of Henry Alfortish that the wall vaults once located along Sixth Street were cleared and demolished. Numerous coping tombs located along this wall today bear Alfortish’s signature.[16] Edward Alfortish assumed sextonship of Lafayette No. 1 in 1942. However, the role of sexton was no longer seen as relevant in the city-owned cemetery. Few burials were made compared to the heyday of Lafayette No. 1, and many of the responsibilities of sexton could be carried out by other city officials. By around 1950, no individual would serve as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 again. The caretakers of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1833 to 1950, built the cemetery as it is seen today. They designed and constructed its tombs, removed and replaced landscape features, fostered its dead and their families, and protected the cemetery from harm. Their names are placed alongside the names of Lafayette No. 1’s most famous residents, in the form of carved signatures at the bases of closure tablets and headstones. The story of this National Historic Landmark cemetery is very much their story. [1] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4; State of Louisiana, The Revised Statutes of Louisiana (J. Claiborne, 1853), 386.

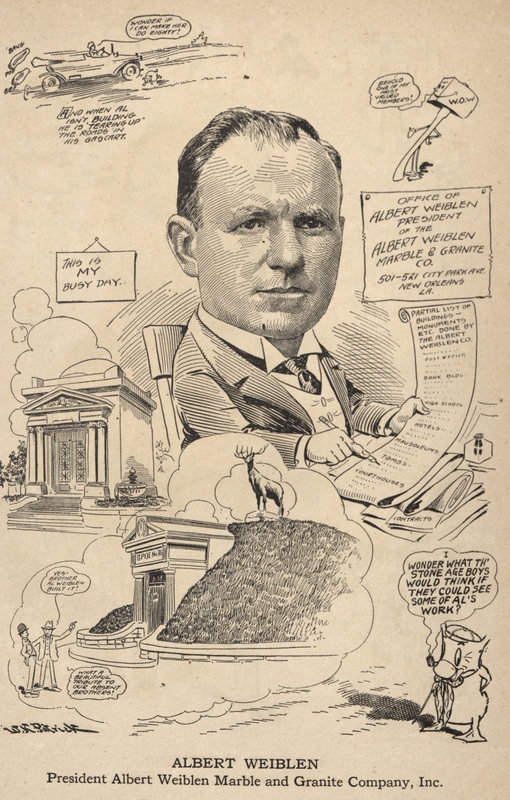

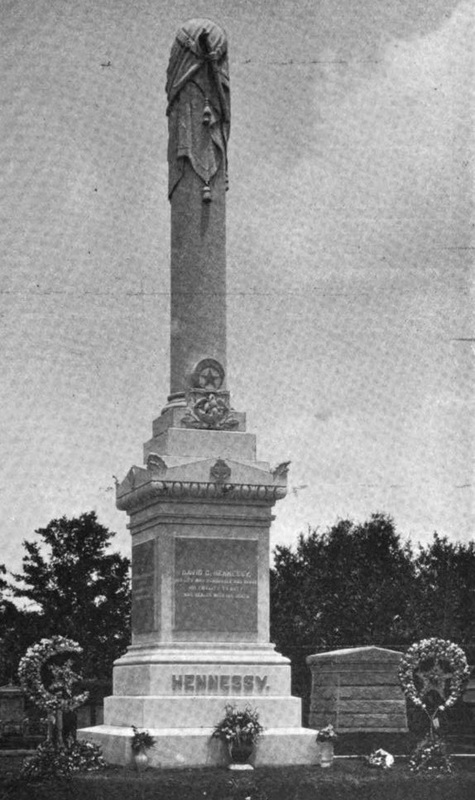

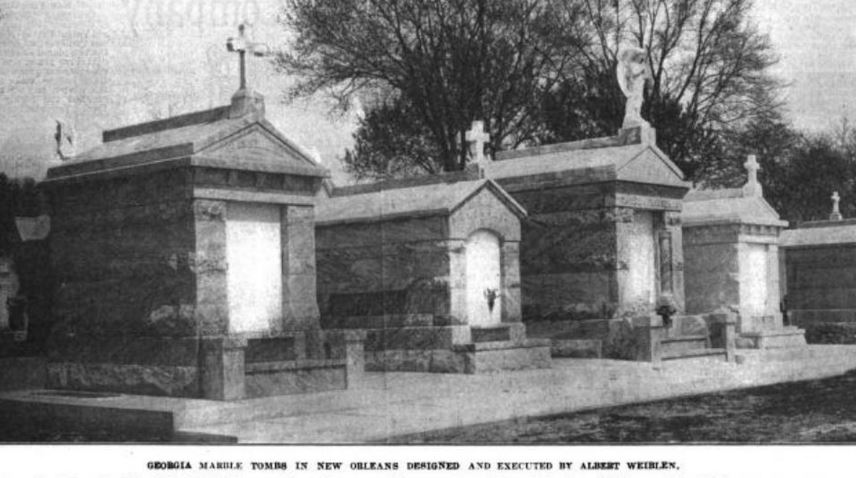

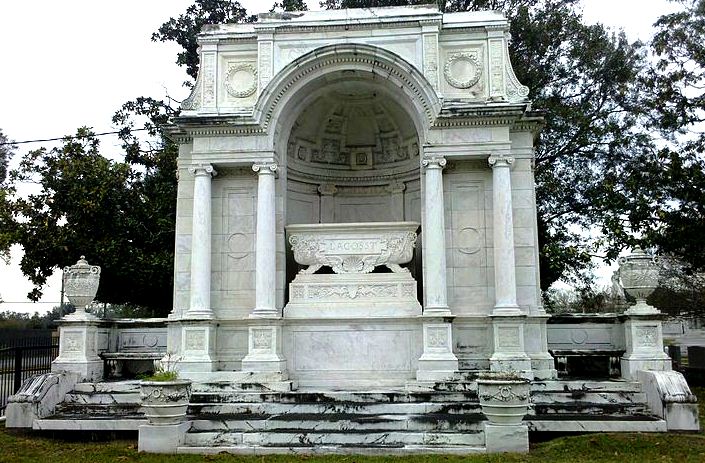

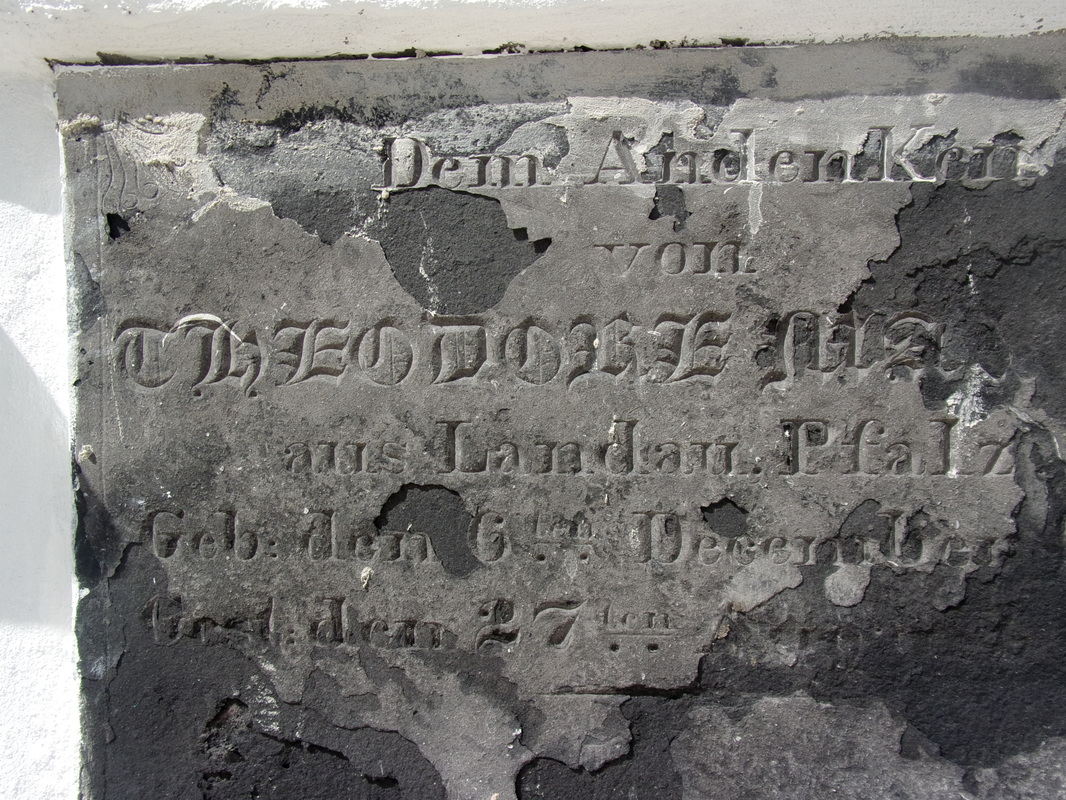

[2] “City Intelligence: Board of Health,” Daily Picayune, August 4, 1853, 1. [3] Ibid.; Currency evaluation oriented around historic standards of living, these costs equate to approximately $20-$40 per interment and $81 (2011 dollars) for the opening/closing of a tomb or vault. (www.measuringworth.com) [4] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84 (Baton Rouge: Leon Jastremski, 1884), 40. [5] Daily Picayune, February 15, 1855, 6; Mygatt & Co.’s Directory for New Orleans, 1857, W.H. Rainey Compiler. L. Pessou & B. Simon Lithographers, 23 Royal Street, New Orleans, 1857, 49; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for the Year 1859 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1858), 377; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1860 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1859), xvi. [6] Based on a 2012 survey of all signed craftwork in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. The Isaac Bogart tomb, located in Quadrant Three of Lafayette No. 1, is documented in the 1981 Save Our Cemeteries/Historic New Orleans Collection Survey of Historic Cemeteries as having a tablet signed by Phil Harty. The tablet has since been lost. [7] “Sudden Death,” Daily True Delta, August 15, 1861, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 18, 1866, 3. [9] Based on directories and municipal documents. [10] “An Official Suspended,” Daily Picayune, October 9, 1878, page 2. [11] Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1880 (New Orleans: L. Soard’s Publishing Co., 1880), 456; Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1882 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1882), 142; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1883 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1883), 452. [12] “A Singular Case,” Daily Picayune, June 14, 1868. [13] Receipt from J. Frederick Birchmeier to the widow of John Paul, Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 365. [14] Daily Picayune, February 8, 1891, 1. [15] Times-Picayune, January 20, 1926, 2. [16] Receipts for lots Quadrant Three, Lots 16 and 17, Quadrant 1, Lots 270-275, the Moulin, Gonea, Legien, and Bittenbring tombs. Sexton’s book, page 127. Historic New Orleans Collection, Leonard Victor Huber Collection, MSS 365. On May 1, 1957, and only a few months shy of his 100th birthday, Albert Weiblen passed away in New Orleans. In his lifetime, Albert Weiblen was a revolutionary figure in New Orleans cemetery architecture. Under his carving hand, the craft of tomb building would expand from a hyper-local, individual cottage profession into a modern industry – spanning the eastern United States and powerfully altering the landscape of New Orleans cemeteries. A German Immigrant in New Orleans Albert Weiblen was born in 1857 in Metzingen, Wurttemberg, Germany. Sources suggest that he began his work as a sculptor in his homeland, apprenticing in the manner that was traditional for the time.[1] Weiblen immigrated to the United States in 1883 and soon afterward began work with local marble company Kursheedt and Bienvenu. Operational from 1867 to 1901, the company was co-owned by Edwin I. Kursheedt, a prolific stonecutter in his own right who, in addition to work in New Orleans’ Jewish cemeteries and other cemetery stonework, supplied the stone for the reconstruction of the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the late 1880s.[2] At this time, New Orleans’ cemetery stonecutting industry was already changing. The florid, individualized Classical-revival tombs popular from the 1840s through the 1860s had given way not only to new styles inspired by Gothic and Italianate revival aesthetics, but also to economies of scale. The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878 galvanized this trend. In this year, the construction of tombs shifted more to “cookie cutter” and slightly simplified styles, replicated by numerous carvers and builders.[3] Weiblen stepped into the cemetery craft scene in New Orleans at a time when this streamlining of tomb construction was in its infancy. New industrial technology, such as saws and machinery to cut granite and marble, new types of stronger hydraulic cements, and stonecutting technology powered by pneumatic chisels and even sandblasting, had been adopted elsewhere in the country, but were a long way off from making their debut in New Orleans cemeteries.[4] When these new tools and methods did arrive, though, it was often Weiblen who spearheaded their use. In 1887, Weiblen left Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s and started his own marble and granite company.[5] His first office and show room was located at 233 Baronne Street, a location he expanded by 1893.[6] Weiblen’s big break came in 1891 when his company won the contract to construct the memorial obelisk to New Orleans Superintendent of Police David Hennessy. Hennessy was murdered on October 15, 1890, an event which sparked riots in New Orleans and led to the lynching of eleven Italian-Americans. The contest had been open to many New Orleans monument men, including Charles A. Orleans, the city’s prominent monument builder at the time.[7] The monument was described by national trade periodical Stone magazine as “one of the handsomest monuments in New Orleans”: