|

This is Part Two in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here. 1841: St. Patrick’s Cemetery At the same time that Americans from the northeast were moving en masse to New Orleans, a separate wave of immigration from Ireland made a great impact on the city. Immigrants fleeing famine and political unrest in Ireland came to New Orleans and settled mostly in what is now the Faubourg St. Mary neighborhood of New Orleans, abutting the Central Business District and what is now the Crescent City Connection bridge. These immigrants formed what is now Irish Channel, although the boundaries of this neighborhood have changed over time.[1] The neighborhood formed from settlement patterns dependent on the construction of the New Basin Canal. In 1833, the Parish of St. Patrick was founded to accommodate Irish Catholics in the neighborhood. By 1840, St. Patrick’s Church was constructed on Camp Street.

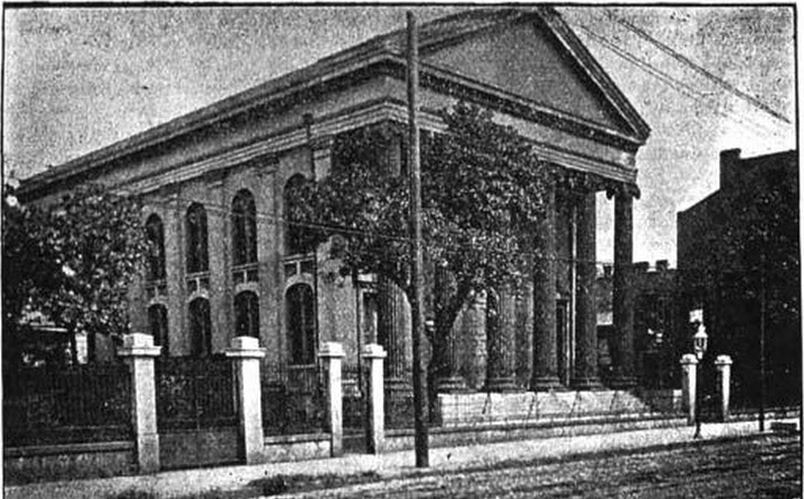

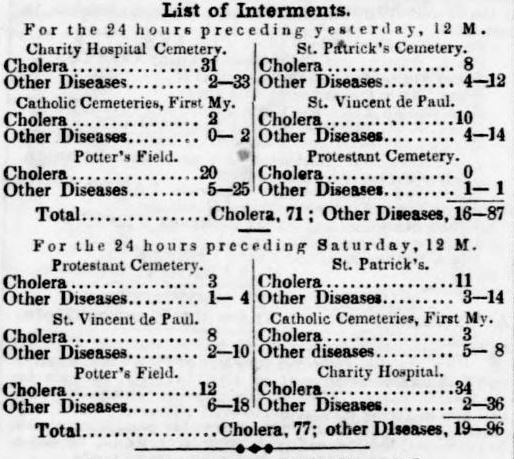

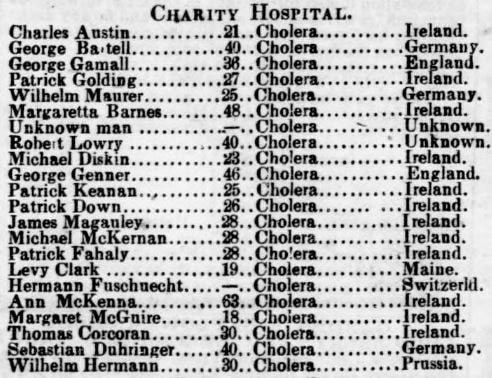

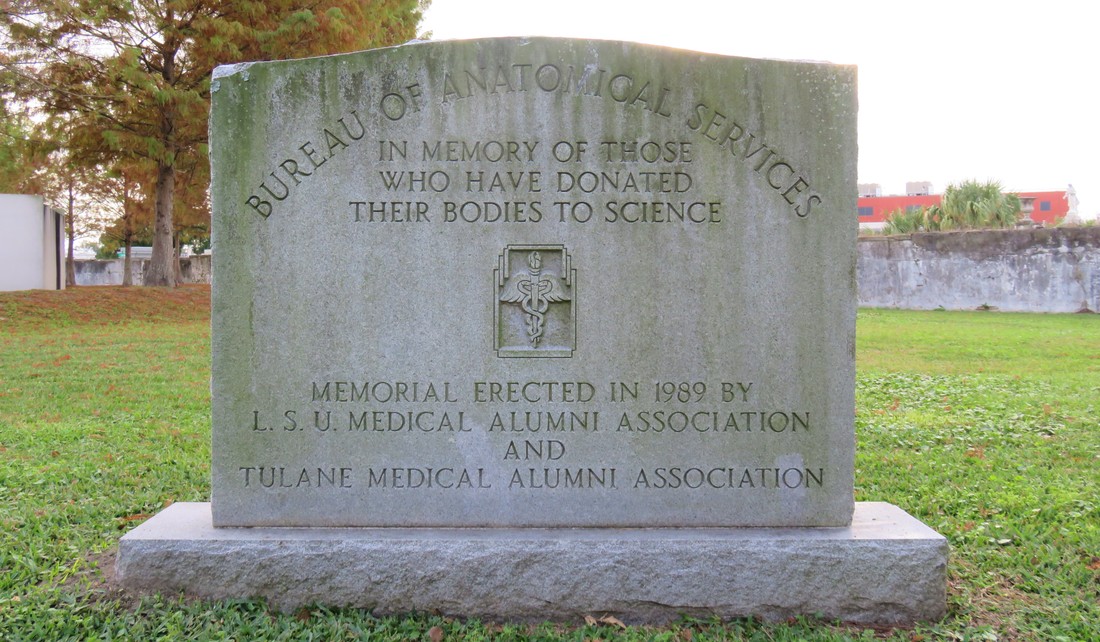

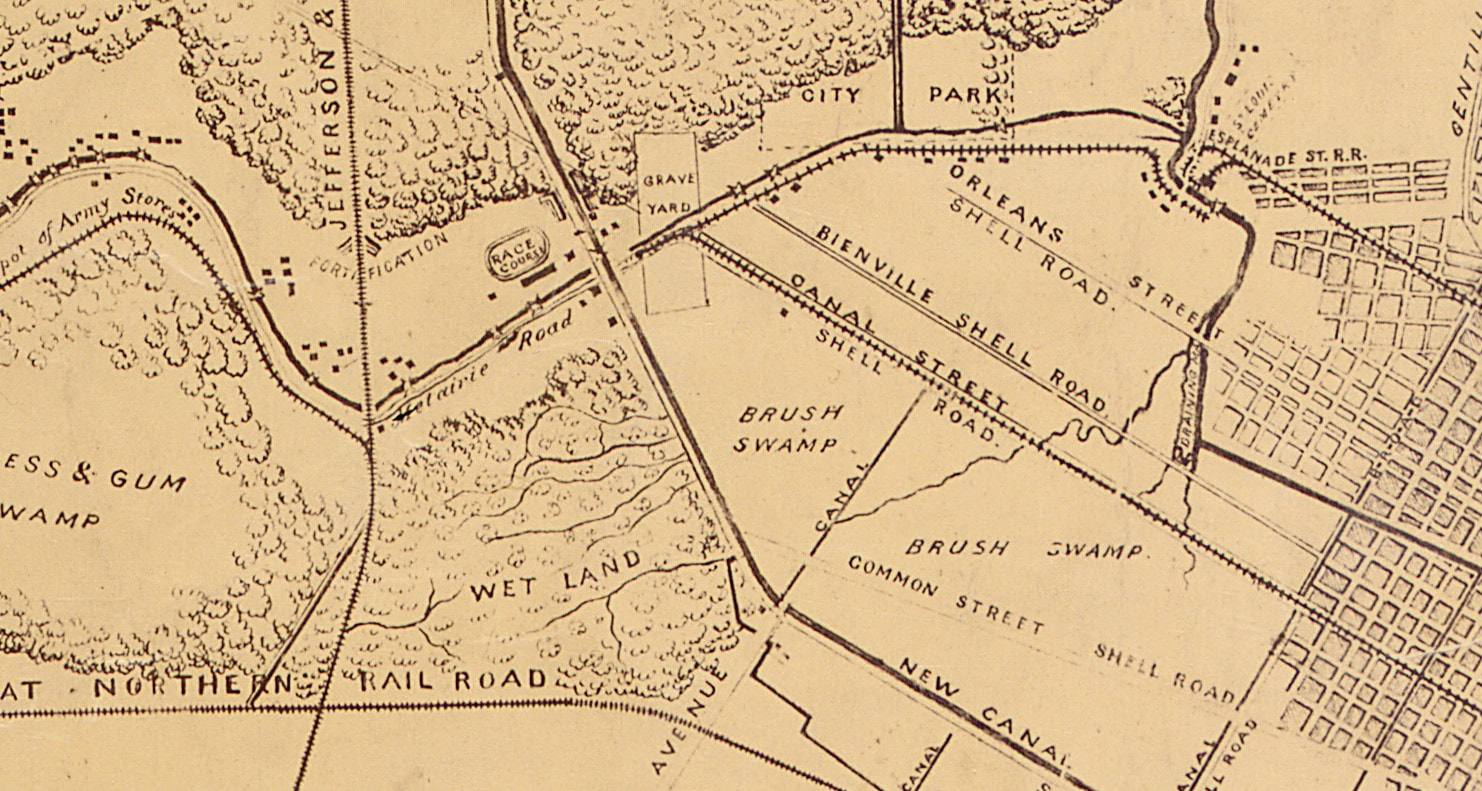

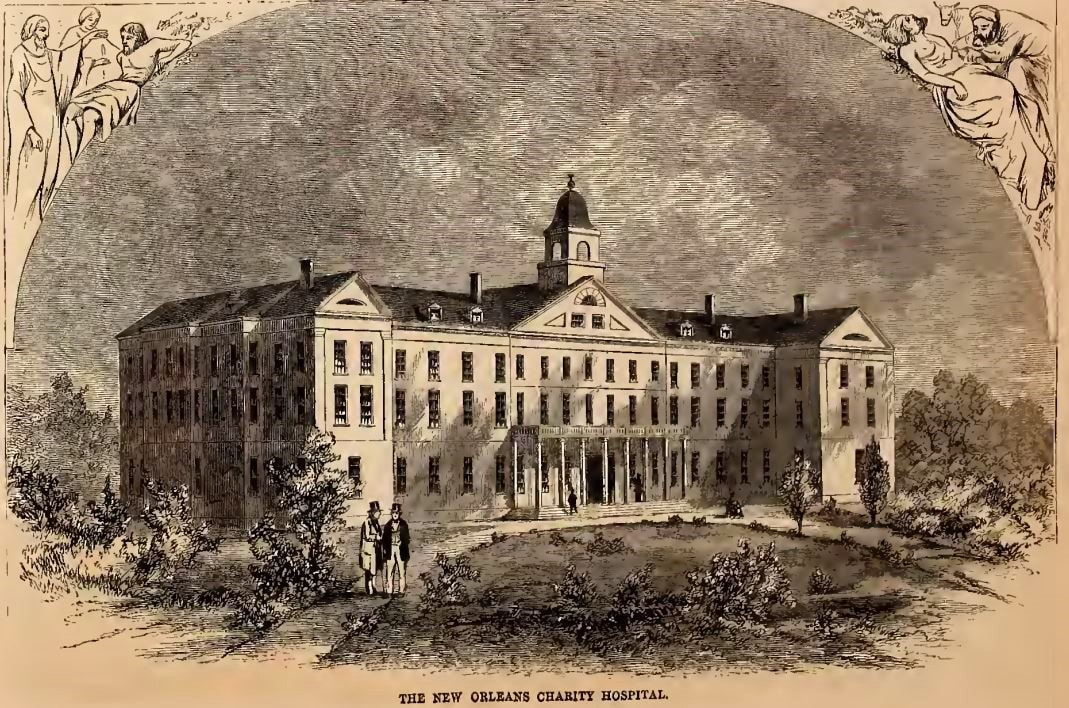

The St. Patrick Cemeteries, so fresh and clean in their snow-white garb and pebbly walks, always attract attention. Here lie the sturdy Irish pioneers who came to New Orleans in the early part of the last century and helped to make her history the proud tale it is… they breathe throughout the spirit of the Catholic faith. Special attention is directed to the beautiful Calvary shrine at the further end of St. Patrick’s No. 1 and the Mater Dolorosa that marks the entrance to St. Patrick’s No. 2.[3] The Calvary statue was designed by then-prominent monument man Charles A. Orleans, consisting of “a wooden cross twenty feet high with life-sized statues of the crucified Christ, Mary Mother of Jesus, His beloved disciple John, and Mary Magdelene. The statues were cast in Paris.”[4] In 1973, in the midst of trends toward community mausoleums, the Calvary was removed to make way for the Calvary Mausoleum. 1846: Dispersed of Judah Cemetery Along with Americans and Irish immigrants to New Orleans, another group of established immigrants and newcomers found their burial place at the end of Canal Street. Jewish people had long lived in New Orleans in small communities, first of primarily Sephardic Jews (of the Spanish-Portuguese tradition) from the Caribbean and England, then later Ashkenazi Jews from Germany and Alsace-Lorraine. These communities first organized in 1828 to found Gates of Mercy congregation, which had a synagogue on Rampart Street near St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Gates of Mercy was an Ashkenazi congregation, and Sephardic Jews in New Orleans sought their own place of worship. This hope was fulfilled in 1846 when organizer Gershom Kursheedt helped aging benefactor Judah Touro found congregation Nefuzoth Yehudah (Dispersed of Judah) in 1846. Dispersed of Judah, a Sephardic congregation, was one of many religious organizations to benefit from Judah Touro’s generous will, which also founded Touro Infirmary, later to become Touro Hospital. In 1881, Dispersed of Judah and Gates of Mercy congregations would merge. The new congregation was eventually renamed Touro Synagogue. In the same year Dispersed of Judah congregation was founded, property adjoining St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2 along Canal Street was purchased for a cemetery. Dispersed of Judah was the second Jewish cemetery in New Orleans. Gates of Mercy had established a cemetery on Jackson Avenue near Saratoga Street in 1828, but this cemetery was demolished in 1957, part of a trend that will be discussed in a later part of this series. Thus, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery is the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. Members of Dispersed of Judah congregation were often tied to English colonial or business interests, arriving in New Orleans from the English-colonized Caribbean or New York. This Anglo-cultural tie, as well as a religious need to bury belowground, allowed Dispersed of Judah to grow into a small version of a northern cemetery. The landscape today retains some elements of this – box tombs and obelisks, trees, and raised monuments. The cemetery is probably best known for the marble monument of Lilla Benjamin Wolf (died 1911), carved into the shape of an empty chair with foot stool. A local story tells the sale of Mrs. Wolf sitting in her chair in life, outside her family’s shop, calling potential customers inside. This may have been a deeply personal choice of monument for the Wolf family, although “the empty chair” was also a common funerary symbol at the turn of the century. 1848: Charity Hospital Cemetery By 1848, Charity Hospital was an institution nearly as old as New Orleans itself. Founded in 1732, the hospital provided care to all patients without regard to race, nationality, religion, or sex. Throughout the nineteenth century, Charity Hospital cared for thousands of newly-arrived immigrants who fell ill after the trans-Atlantic journey, or who were especially susceptible to New Orleans epidemics of yellow fever and cholera.[5]  Charity Hospital's fifth building, in use from 1832 to 1939. Located on Common Street between St. Mary and Girod Streets, it was replaced in the 1930s by "Big Charity," a building designed by Weiss, Dreyfus, and Seiferth, who also designed the Louisiana State Capitol at Baton Rouge. Image from Harper's Weekly, September 3, 1859, via archive.org.

The firemen used axes to demolish the fence to save the [adjoining] St. Patrick’s Cemetery property, but nothing could be done to prevent destruction, and, after the flames had consumed the grass, covered the graves under smoldering ashes, with no crosses or headboards to identify the original plots, nothing was left for the friends or relatives of the dead to distinguish one grave from the other.[7]  Charity Hospital Cemetery in 2003, looking over the fence from St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2 and toward Canal Street. The flags present on the site suggest that it may have recently been mapped using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to identify gravesites. Photo by Dale Boudreaux, via usgenwebarchive.com Charity Hospital Cemetery would receive scores of burials each day during successive yellow fever and cholera epidemics. Later, the cemetery would also receive the bodies of those who had donated their remains in death as medical school cadavers. After Hurricane Katrina, the cemetery would be revised into a new kind of memorial. 1849: Odd Fellows Rest Charity Hospital was the third cemetery to be established at the end of Canal Street. By that time, the land was still overwhelmingly rural, with few structures save the Halfway House and Toll House along the Shell Road, and the towering Egyptian pillars of Cypress Grove. But around the same time Charity Hospital Cemetery was established, another great landmark was in the works. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), a fraternal organization established in England in the 1700s, had founded a local lodge in New Orleans in 1833. The origins of IOOF’s name seem debated; one explanation has been that the “Odd” designation came from the society’s openness to all members despite trade or occupation. The official IOOF website tells a different story: “…it was odd to find people organized for the purpose of giving aid to those in need.” Indeed, the IOOF’s stated purpose is “Visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead and educate the orphan.” The Odd Fellows were also known as the “Three Link Fraternity,” a reference to their motto “Friendship, Love, and Truth,” often symbolized by the three-link chain. By 1858, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana had more than twenty subordinate local lodges, including the Crescent, Teutonia, Howard, Magnolia, Covenant, and Polar Star Lodges, all beneath the IOOF Grand Lodge umbrella. In addition to establishing widows’ and orphans’ assistance, and constructing one, and then another imposing Odd Fellows Hall building, the local Odd Fellows sought to establish their own cemetery by the late 1840s. Odd Fellows cemeteries were a national phenomenon in the nineteenth century, and can still be found in places as disparate as New Jersey, Texas, Nebraska, California, and Oregon. New Orleans Odd Fellows sought to do the same. Previous to this time, the land acquired by respective cemetery owners like St. Patrick’s Church, Charity Hospital, and the Firemen had been allotted using lines of property demarcation corresponded to Lake Pontchartrain and not the Mississippi River, leading to the long lots exemplified best by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1, 2, and 3. These property lines ran across Bayou Metairie at angles, leaving a small triangle of land wedged between St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Bayou Metairie, and Canal Street. In 1848, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana IOOF purchased this small triangle of land for use as their cemetery – the first, but not the last fraternal cemetery at the end of Canal Street.[8] On February 26, 1849, the various Odd Fellows Lodges converged on the Place d’Armes (Jackson Square) to form an “exceedingly beautiful” procession to celebrate the consecration of Odd Fellows Rest.[1] The parade of hundreds was decked in black crape, banners, and emblems of the many symbols recognized by the Odd Fellows. They marched through the French Quarter in a serpentine route, up one street and down another, across Canal Street and through the American Sector (now the Central Business District) where they converged at the New Basin Canal and boarded carriages to proceed up the New Shell Road to the Halfway House.[2] At the Halfway House, the Odd Fellows re-formed their procession, following a carriage drawn by six gray horses and carrying a sarcophagus containing the remains of sixteen Odd Fellows, exhumed from other cemeteries to be re-interred at Odd Fellows Rest. The procession entered through the cemetery’s gate, a granite Egyptian Revival post-and-lintel that mirrored in style if not size the grand entrance of Cypress Grove immediately across Canal Street. Once inside, the parade ended at the center of the cemetery, where a tomb had been prepared. Poems were read and oratories recited, and the remains reburied. The entrance to Odd Fellows Rest would remain at the center of its Canal Street boundary for more than fifty years. The granite entryway was enclosed by two cast-iron gates produced in Spain for the Odd Fellows that portrayed dozens of the Order’s symbols: cornucopia, beehives, globes, books, shepherd’s staffs, stars, axes, and a mother protecting four children. The gates were surmounted by finals depicting the sun and moon, and atop all of this was the perennial Odd Fellows Symbol, the heart-in-hand. In the mid-twentieth century, New Orleans photographer Clarence John Laughlin would capture the gates in their historic context, complete with detail and careful multichromatic paints. By the 1970s, much of the original ironwork had been stolen or lost. Within the walls of Odd Fellows Rest, the cemetery would be populated by hundreds of enclosed wall vaults, belowground burials, high-style tombs, and even a tumulus. In the 1850s, local sculptor and stonecutter Anthony Barret (1803 – 1873) constructed a 48-vault society tomb for the Teutonia Lodge of the Grand Order IOOF. The society tomb, later transferred to Southwestern Lodge No. 42, was designed reminiscent of an Italian loggia, with each arched group of vaults framed by inverted torches carved in marble. The Teutonia Lodge tomb was surmounted by marble urns on each corner of its roof. At the primary façade of the tomb was the piece-de-resistance of the structure: a remarkably ornate marble panel carved with dozens of symbols of the Order, each framed with fine scrollwork carved in relief. At the center of the panel, the protecting mother sits nursing a baby and wrapping her cloak around another child. Anthony Barret was well known for his remarkable stonework, carving some of the finest relief sculptures found in the Lafayette Cemeteries and elsewhere. Even still, the Teutonia Lodge tomb is the greatest artistic accomplishment of Barret’s to survive into the present day. [1] Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma, 172.

[2] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 132-133, 139-140. [3] The New Orleans Picayune, The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: The Picayune, 1904), 152. [4] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 33. [5] John E. Salvaggio, New Orleans’ Charity Hospital: A Story of Physicians, Politics, and Poverty (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1992), 35-45. [6] “Second Municipality Council,” Daily Picayune, May 19, 1847, 2. [7] “A Cemetery Blaze: Flames Sweep the Spot where Charity Hospital Dead are Interred,” Times-Picayune, February 27, 1905, 11. [8] An 1833 map of New Orleans from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain shows the intersection of Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal divided into properties belonging to the New Orleans Banking and Canal Company, and illustrates how the property lines correspond with Lake-oriented parcels. A high-resolution of that map is available here. [9] “Consecration of Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, February 27, 1849, 1. [10] Ibid.

1 Comment

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly