|

As the weather cools down, cemetery managers and community groups look to living history performances to inspire support and interest in their historic landscapes. It’s that time of year again! The weather is cooling down, the pumpkins are in their patches, and our minds turn toward the ethereal, mysterious landscapes of cemeteries.

It’s also the time of year when a lot of preservation, heritage, and municipal groups hold annual cemetery fundraising events in the form of living history tours. Events like these connect the public with historic cemeteries in a unique way – visitors walk through the cemetery, often at night or twilight, and meet the “residents” of the cemetery. Through drama (and sometimes music), visitors can connect with the importance of the cemetery to local history and culture. Living history tours are also a whole lot of fun! Wherever you are in the South this year, there is a living history event in a cemetery near you. It might be Natchez City Cemetery’s annual “Angels on the Bluff” tour, a large-scale event that sells out every year, as does Oakland Cemetery’s “Spirits of Oakland” program in Atlanta. But it also might be a smaller event hosted by a local historical society. Check out the listings below to plan your cemetery visit – it makes a great date night or family outing.

0 Comments

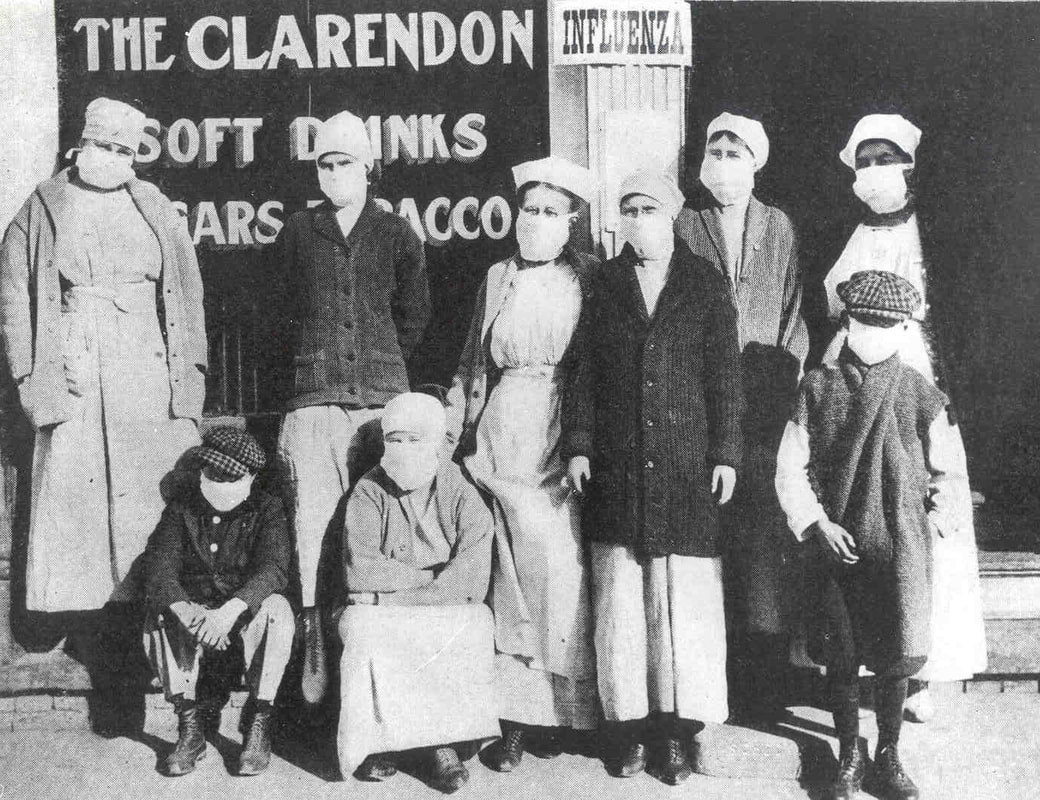

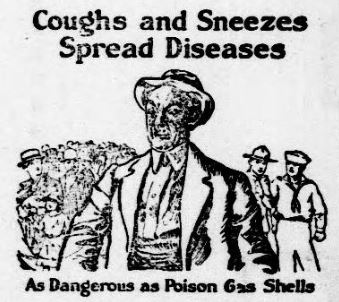

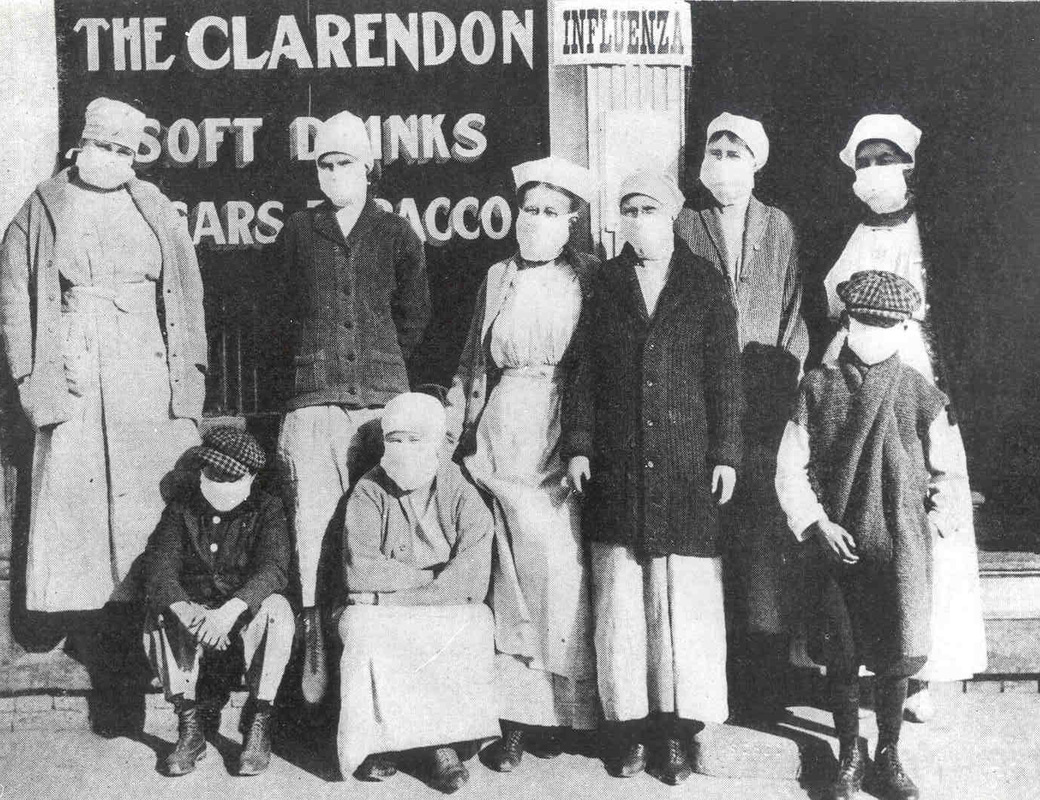

How New Orleans weathered one of the greatest plagues in history. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a worldwide emergency like that which took place in 1918. Modern-day fiction and sci-fi writers have materialized similar fears – there is no shortage of post-pandemic fiction. For example, the HBO series The Leftovers posits a world in which two percent of the world’s population has vanished, the Max Brooks novel World War Z injects zombies into a frighteningly realistic image of how civilization would handle pandemic catastrophe. The list goes on. But we so often forget that something like this did happen. In 1918, a strain of pandemic influenza swept the globe three times, infecting millions and killing five percent of the world’s population. Medical science today cannot pin down exactly where it began. One prominent theory states that H1N1 influenza began with swine farms in Haskell County, Kansas in late January 1918.[1] Like other incidents of mutated influenza virus “jumping” from livestock to humans, it could have fizzled out in the local population. Yet nationwide mobilization in response to the United States’ entry into World War I meant that military camps were ubiquitous and population movement intensified. Influenza was transported to Camp Funston, Kansas, where it spread to other camps, other towns. The first wave of influenza traveled from the United States to Brest, France, in April 1918. Within the next month, it spread to Spain. Spain, neutral during World War I, was less likely to censor press reports of the disease. Hence, although the U.S., Britain, and France saw just as many cases of influenza, such incidents were not reported. The uneven press coverage created the appearance of the disease originating in Spain, giving it the incorrect moniker “Spanish Influenza.[2]” Influenza was documented in China and India by May 1918. The spring wave, however, was comparatively mild. The second wave of Fall 1918 would be devastating. As the summer of 1918 wore on and Allied victories in Europe continued, state and federal medical officials assumed disaster had been averted.

Attempts to quarantine the sick and curb the spread of influenza were often thwarted by the pressures of total war. In one especially salient instance, insistence from upper-crust social circles in Philadelphia caused medical leaders to allow a War Bonds parade to take place, despite the mounting evidence of an influenza epidemic. New cases of the illness soared in the days after this large public gathering. In metropolitan areas, the flu jumped from military to civilian populations, and then spread.

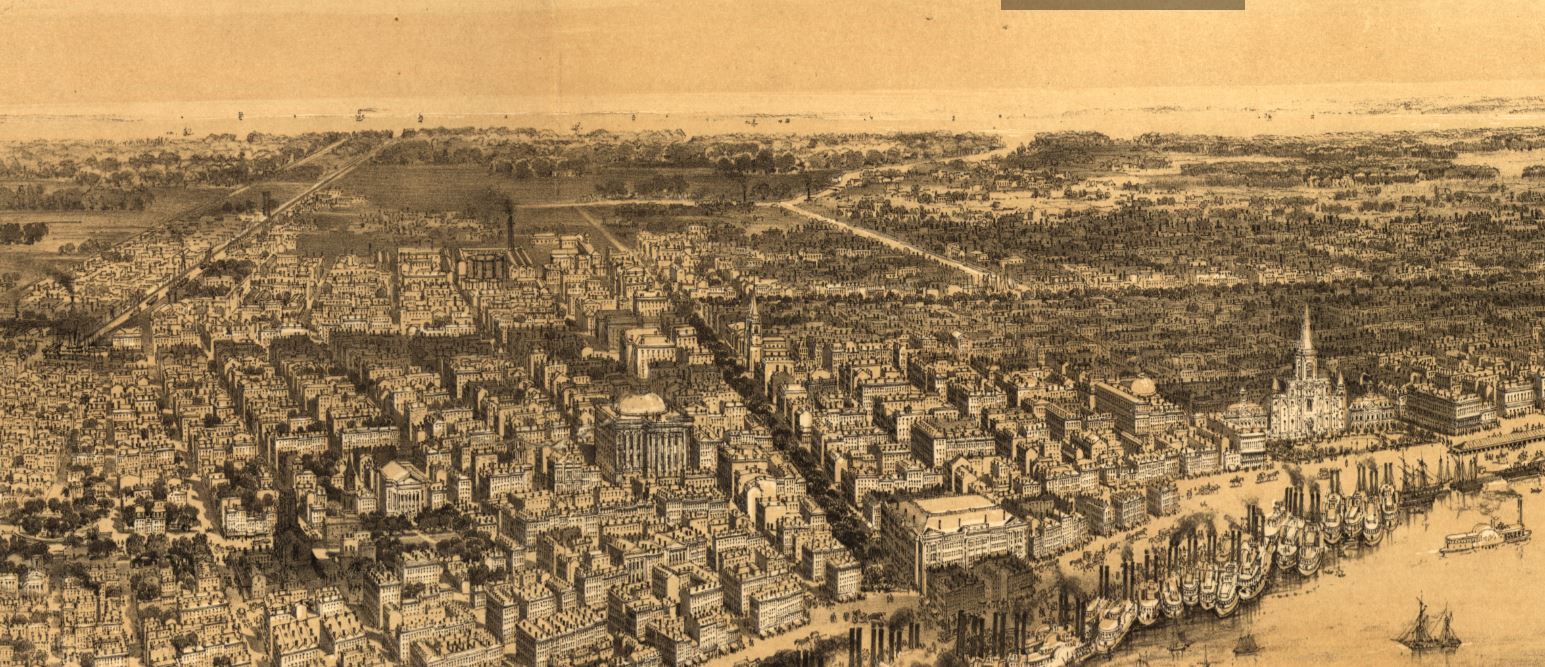

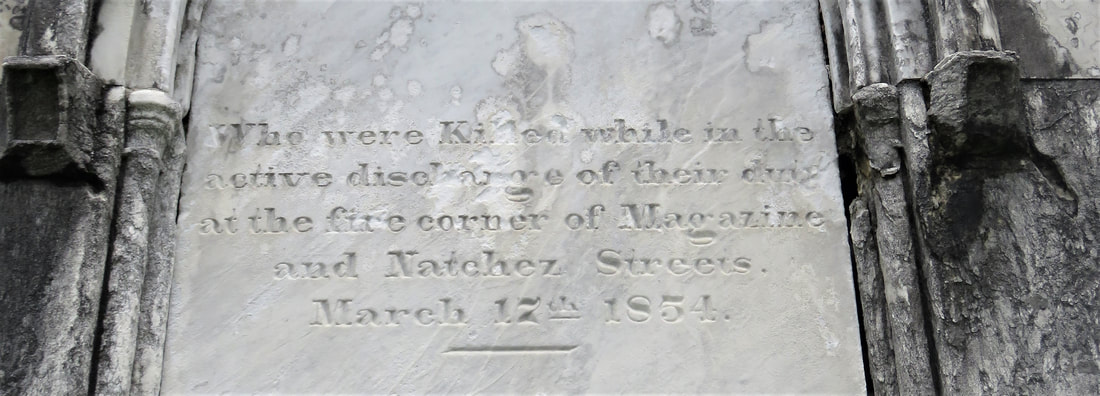

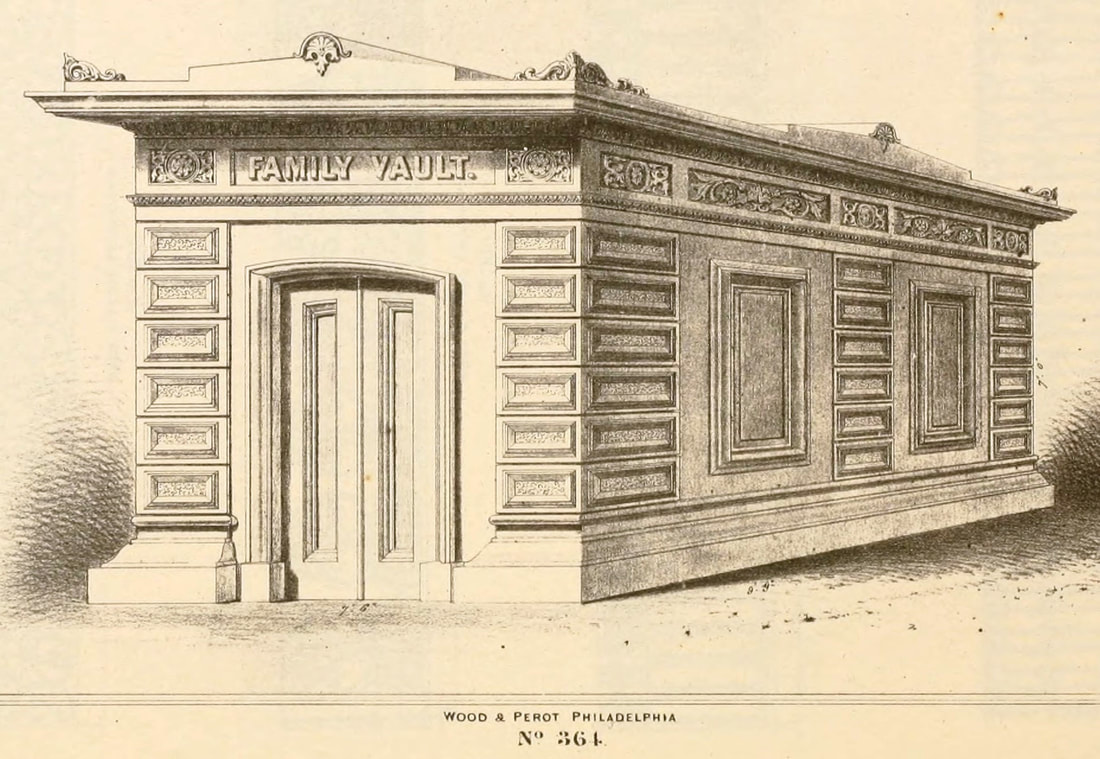

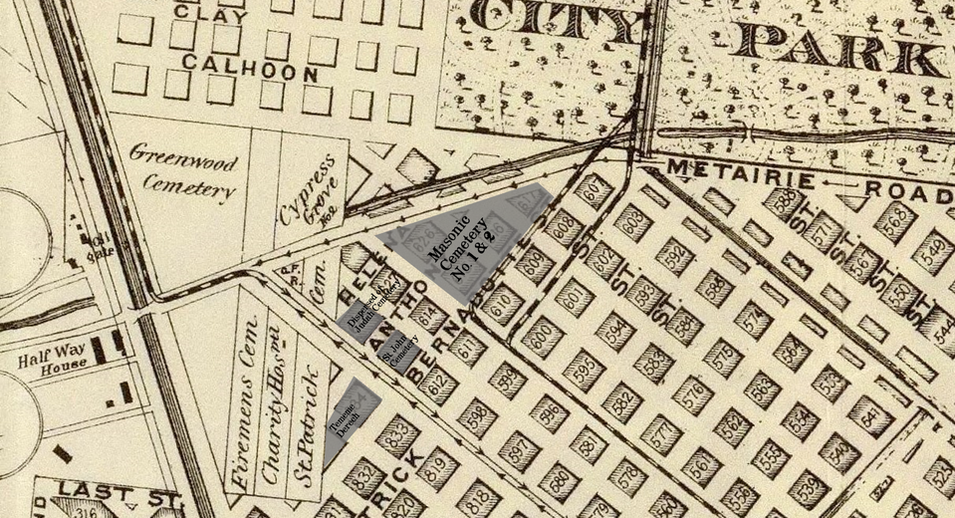

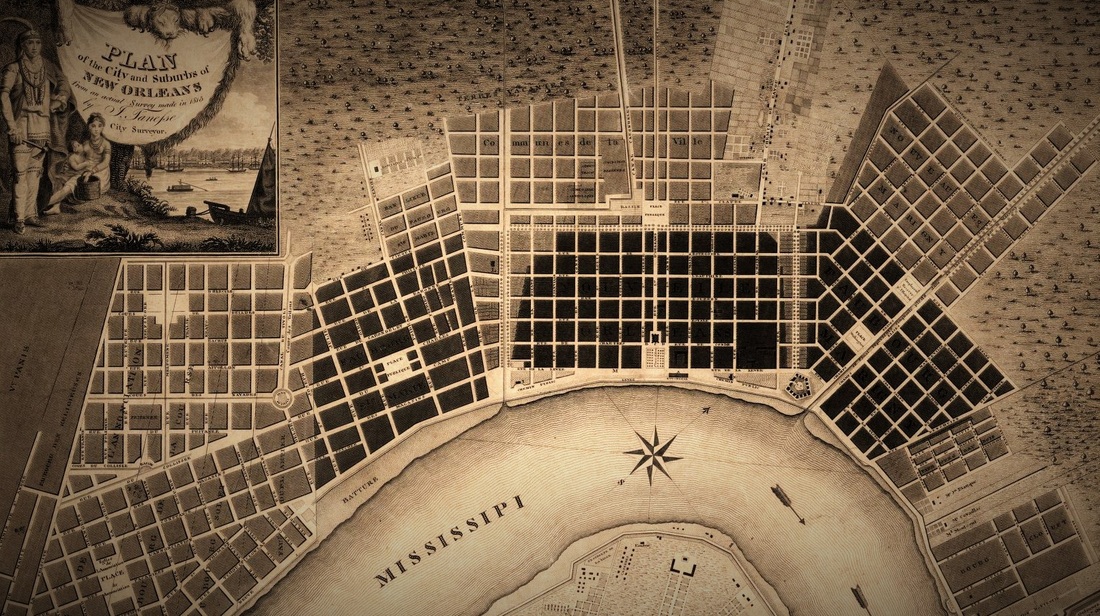

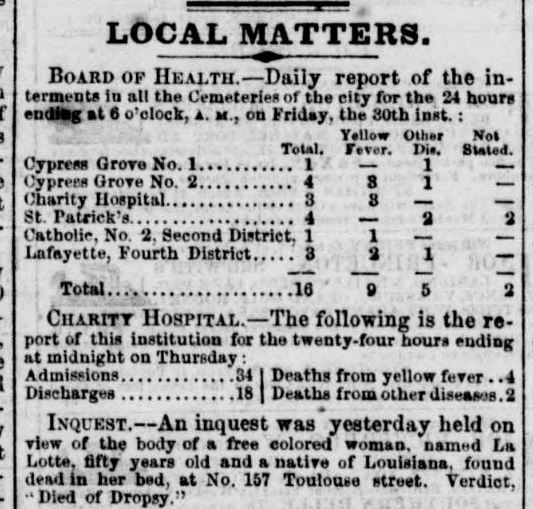

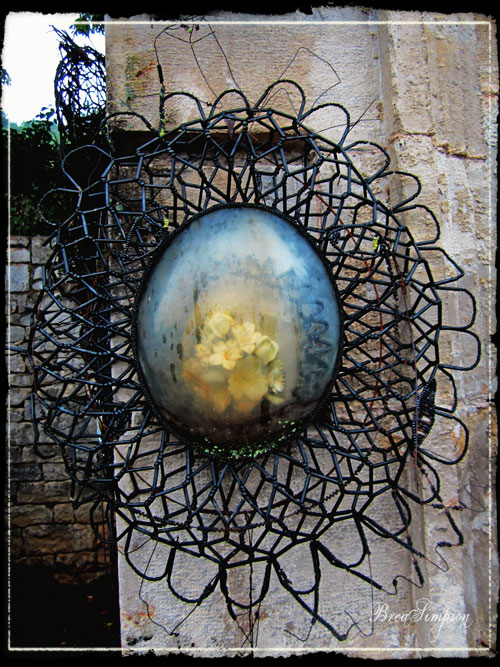

One hundred years ago this month, influenza arrived in New Orleans. This is Part Three in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here and Part Two here. 1852: Greenwood Cemetery By 1850 the terminus of Canal Street remained mostly undeveloped. On each side of Canal approaching Bayou Metairie were the predominantly belowground Dispersed of Judah, St. Patrick’s, and Charity Hospital Cemeteries, each likely bounded by wooden fences. Improvements like the Halfway House, the Toll House, and the walls of Odd Fellows Rest modestly framed the monumental entryway to Cypress Grove Cemetery. Cypress Grove itself was more than a decade old and flourishing as a garden cemetery full of trees and landscape features – despite a fire in 1848 that destroyed many plantings.[1] The Firemen’s Charitable Association had been quite successful in developing Cypress Grove, so much so that demand for lots overran supply. In 1852, the FCA opened Greenwood Cemetery across Bayou Metairie from both Odd Fellows and Cypress Grove. Its eastern boundary would adjoin Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also known as Charity Hospital No. 2. In some ways, Greenwood Cemetery would be a continuation of Cypress Grove – dedicated to the memorial of fallen firemen and stylistically influenced by Anglo-Protestant aesthetics over those of Creole New Orleaneans. In fact, it’s likely no accident that Greenwood Cemetery shared its name with a famous garden cemetery in New York, founded in 1838. However, Greenwood would not accommodate the landscape features and lofty architecture so well fostered by Cypress Grove. Instead, the new Firemen’s cemetery would be organized in compact, neat rows that mirrored the kind of order seen in contemporary cemeteries like St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 on Esplanade Avenue (est. 1854). A grand dedication ceremony like those seen at Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows Rest would not be held for Greenwood Cemetery. This may have been the result of an almost immediate cholera and yellow fever epidemic following the cemetery’s opening. The 1853 yellow fever epidemic would kill as many as 12,000 people in New Orleans, quickly making Greenwood a vital burial ground. Unlike Cypress Grove or Odd Fellows Rest, Greenwood Cemetery was not enclosed with a masonry wall, but an iron fence. This left the southern boundary of the cemetery visually open to the bayou that meandered in front of it. The grassy space left room for display of more impressive monuments. Decades would pass, however, before the most iconic monuments of Greenwood would appear. The Confederate monument (1873), Firemen’s monument (1887), and Elk’s Lodge tumulus (1911) did not yet rise above the bayou. Instead, one of the first monuments to be erected in Greenwood Cemetery would be that of two martyred firefighters. On March 16, 1854, Daniel Woodruff and William McLeod responded to a fire on Magazine Street as members of Mississippi Fire Company No. 2. In the blaze, a wall fell upon Daniel Woodruff and he was killed in action. Later, William McLeod died of injuries sustained in the fire.[2] Exactly one year after the tragic fire, the FCA laid the cornerstone of the fallen men’s memorial tomb. The Firemen traveled to Greenwood Cemetery in a procession to Metairie Ridge where the cornerstone was laid. In Masonic tradition, the architect of the tomb, Sheppard Reynolds, presented the Grand Master of the FCA with a plumb, square, and level with which to test the cornerstone. After it was pronounced level and plumb, the stone was anointed using vessels of corn, wine, and oil. After an oratory, the procession retreated.[3] The Woodruff-McLeod tomb, similar in style but not size to the Teutonia Lodge tomb, was completed by stonecutter and tomb builder Newton Richards (1805 – 1874), who also constructed the Irad Ferry monument. Each arched loggia-like vault memorializes the life and service of Woodruff and McLeod. Yet only one of the two martyrs are actually buried in this tomb. When the time came to re-inter William McLeod in Greenwood his widow objected. His body remained at Girod Street Cemetery. It is unclear where McLeod may have been re-interred after the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery in 1957.[4] Newton Richards had by 1859 constructed the Irad Ferry monument, the Woodruff-McLeod monument, dozens of other tombs in New Orleans cemeteries, and even the granite pedestal atop which the Andrew Jackson statue is mounted in Jackson Square.[5] A man from New Hampshire who specialized in granite monuments, Richards was especially active in the Anglo-Northern associated cemeteries. In 1859, he would once again shape the budding landscape of Greenwood Cemetery by erecting the memorial of former New Orleans mayor Abidel Daily Crossman in Greenwood Cemetery. A.D. Crossman served four consecutive terms as mayor of New Orleans, weathering the city through natural disasters like Sauve’s Crevasse and the 1853 yellow fever epidemic. He oversaw the re-joining of the city from three separate municipalities into one united city government, and local military response to the Mexican-American War. Crossman was from Massachusetts and had long been a friend of the city’s firefighters – serving as a firefighter himself under Eagle Company No. 7.[6] For Crossman, Richards erected a classical Doric column carved of granite and surmounted with an urn. The granite die and stacked bases atop which the column sits are enclosed with cast iron fencing, the corners of which are each topped with cast iron flaming lamps. The cemeteries at the end of Canal Street were tied not only by geography but, in some cases, mutual origins and culture, specifically that of Northern-born Americans. For this reason, it is no surprise that stonecutters and tomb builders with similar backgrounds tended to concentrate their work in Cypress Grove, Greenwood, and Odd Fellows. In fact, the first sexton of Greenwood Cemetery, Daniel Merritt, also served as sexton in Odd Fellows Rest. Carved tablets signed by Merritt are found in all three cemeteries.[7] Greenwood Cemetery greeted a peculiar new tomb construction in the 1860s – tombs built of brick and mortar but clad in cast-iron panels. This style was not exclusive to Greenwood (Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 had the Karstendiek tomb by 1866, and Cypress Grove famously houses the Leeds cast-iron tomb), but Greenwood gathered the highest concentration of these unique structures. Four of these tombs (Marks, Enberger, Summers, and Hetion) were identical catalog-order tombs from the ironwork firm of Wood, Miltenberger, and Company, which had a branch in New Orleans. The Edwards tomb, also of cast iron, was a custom construction erected in 1861 across the aisle from the Woodruff and McLeod tomb. 1858: Tememe Derech Cemetery Jewish immigration to New Orleans continued through the first half of the nineteenth century. Some Jews emigrated from France, Germany, and the contested territory of Alsace-Lorraine between the two countries. By the 1850s, however, other Jewish people from Eastern Europe began to arrive, fleeing pogroms in their home countries. In 1858, Polish Jews formed the Orthodox congregation of Tememe Derech (“The Right Way”). This congregation was the first Eastern European Jewish congregation to construct a purpose-built synagogue, once on Carondelet Street. Tememe Derech also established its own cemetery across Canal Street from Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, on what is now Botinelli Place.[8] Tememe Derech was not the only Eastern European Jewish congregation in nineteenth century New Orleans. Over time, other congregations formed and merged, and Tememe Derech itself merged with others in 1904 to form Beth Israel Congregation. The new congregation constructed a synagogue on Carondelet Street and designed by Emile Weil. This building is now the New Home Family Worship Center at 1616 Carondelet.[9] As congregations formed and merged among Eastern European Jews in New Orleans, Tememe Derech’s original cemetery would become the burying ground for other congregations, namely Chevra Thilim and later Beth Israel. In 1916, Beth Israel would construct a Metaher house (a traditional chapel for the cleansing of bodies) at the entrance to the Canal Street cemetery. This structure was demolished in the 1960s.[10] The 1860s: A Decade of Change With the addition of Greenwood and Tememe Derech Cemeteries in the 1850s, the confluence of Canal Street, New Basin Canal, and Bayou Metairie had six cemeteries within its bounds. In 1854, New Orleans City Park was founded. Larger than New York’s Central Park and home to the largest concentration of old-growth live oak trees in the world, City Park would add to the character of this area as a place of diversion and rural retreat. A portion of Bayou Metairie running through City Park would eventually be closed off to become a park lagoon. Today, this lagoon is the last remaining vestige of Bayou Metairie. New Orleans as a city was growing in both population and urbanized area. In 1861, the New Orleans City Railroad Company constructed a rail line extending up Canal Street from its foot at the Mississippi River all the way to Bayou Metairie, expanding access and development. The next year, the second fraternal cemetery in the area would arrive when Masonic Cemetery No. 1 and 2 opened at Bienville Street and Bayou Metairie. Despite steady development in the area, it would not escape the humbling effects of natural forces. Metairie Ridge had escaped the flooding of Sauve’s Crevasse in 1849, but would not be so lucky in 1860, when both New Basin and Carondelet Canals overflowed their levies and flooded the area.[11] Another crevasse in 1871 would inundate the cemeteries even more, when the New Basin Canal levy breached at the Halfway House, causing water to flow into the cemeteries.[12] By 1862, additional railroad track was present running alongside Bayou Metairie to the Halfway House. Through the Civil War and into the 1870s, New Orleans’ street grid would encroach toward the cemeteries. Nearby City Park, home to the famous “dueling oaks,” would not be the only venue for such bouts. In 1868, a duel between a Mr. “M” and a Mr. “G” was fought near the Halfway House with swords as the chosen weapon. Although neither man died in the match, neighbors in the vicinity soon afterward requested a police station be placed at the Halfway House – a request that the city council granted.[13] 1867: St. John Cemetery Another cemetery would join the landscape of Canal Street in 1867. Founded by German St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church, St. John Cemetery was the second Protestant cemetery in New Orleans (the first was Episcopal Girod Street Cemetery, founded 1822). St. John Cemetery was owned and managed by the church through the nineteenth century and was religiously restricted. Wrote Leonard Victor Huber, who later co-owned the cemetery with his family, under the church’s ownership “secret societies were not allowed to hold ceremonies in it, and Catholic priests were forbidden by their bishops to officiate services in it.”[14] St. John Cemetery was managed by a sexton who lived on the grounds. The small cemetery at Canal and Bernadotte Streets would develop over time into a typical New Orleans cemetery until the 1920s, when circumstances would transform it into a completely different type of cemetery.[15] The Civil War New Orleans was captured by Union forces in late April 1862, early in the Civil War. The American Civil War was also a time in which the culture and practice of death changed nationwide. Soldiers, accustomed to the concept of a “good death” instead died on battlefields, often buried where they fell. In New Orleans, bodies of both Union and Confederate soldiers were received, transported from elsewhere and buried in places like Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 and Chalmette Cemetery in St. Bernard Parish. After the Civil War, questions of claiming and memorializing the dead dominated conversation. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also referred to as Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2, received the remains of both Federal and Confederate soldiers. In the 1870s, when the remains of Confederate soldiers were relocated from Chalmette Cemetery to Greenwood Cemetery, remains from other cemeteries including Cypress Grove No. 2 were reinterred in the same place. This effort was headed by the Ladies Benevolent Association of New Orleans, who erected the Greenwood Confederate monument atop this mass grave of 600 soldiers in 1873. The “Old Soldier’s Home,” established in 1866 by the State of Louisiana for Confederate veterans, also had a society tomb in Greenwood Cemetery by 1868. Remains of Union soldiers were also removed from Cypress Grove No. 2, as well. In the 1920s, as the old potter’s field was beginning to be redeveloped as a road and dumping ground, Federal soldiers were disinterred from Cypress Grove No. 2 and relocated to Chalmette National Cemetery. On All Saints’ Day, November 1, 1868, New Orleaneans observed the yearly tradition of decorating and visiting graves. The New Orleans Republican offered a glimpse of the Canal Street cemeteries on this day, noting the “noble monuments” of Cypress Grove, and nodding to the society tombs of the Deutscher Louisiana Draymen Verein (now mostly demolished), and the New Orleans Typographical Union in Greenwood Cemetery. Odd Fellows was described as well, “with its specious avenues bordered with trees and lined with the tombs of good and charitable men, is one of the most attractive of the homes of the dead.”[16] The rural cemeteries at Canal and City Park Avenue had matured into landscapes of marble, granite, limewash, and green landscaping. Each cemetery enclosed by masonry walls, picket fences, or painted ironwork, they framed canal and bayou as carriages and barges passed through. As much as the landscape had changed over three decades since the New Basin Canal opened, it was about to transform even further with the founding of an entirely new cemetery, the likes of which the city of New Orleans had yet to see. [1] Thomas O’Conner, editor, History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: Thomas O’Conner, 1891), 75.

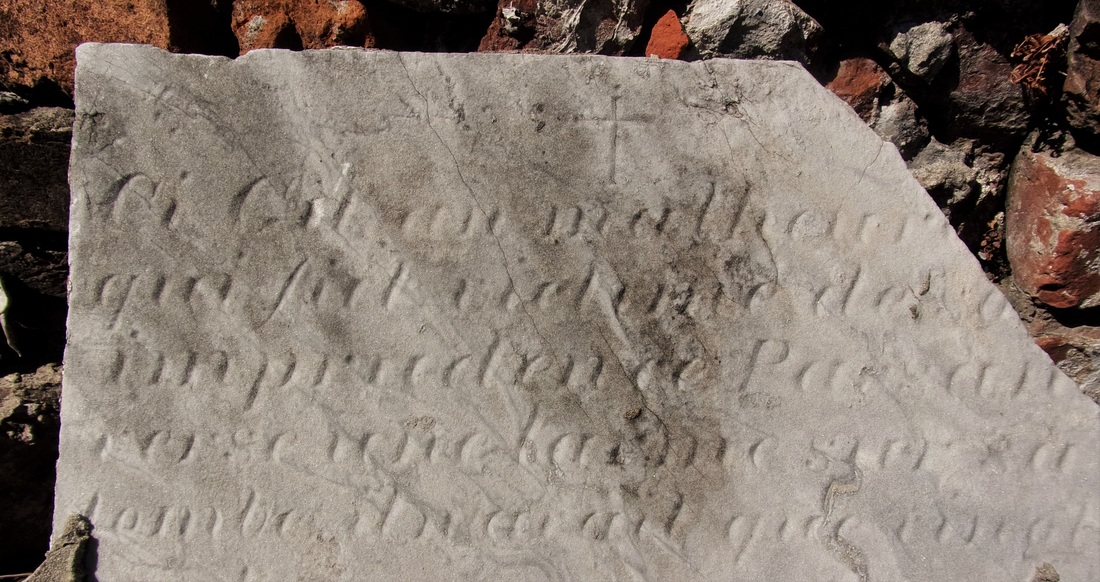

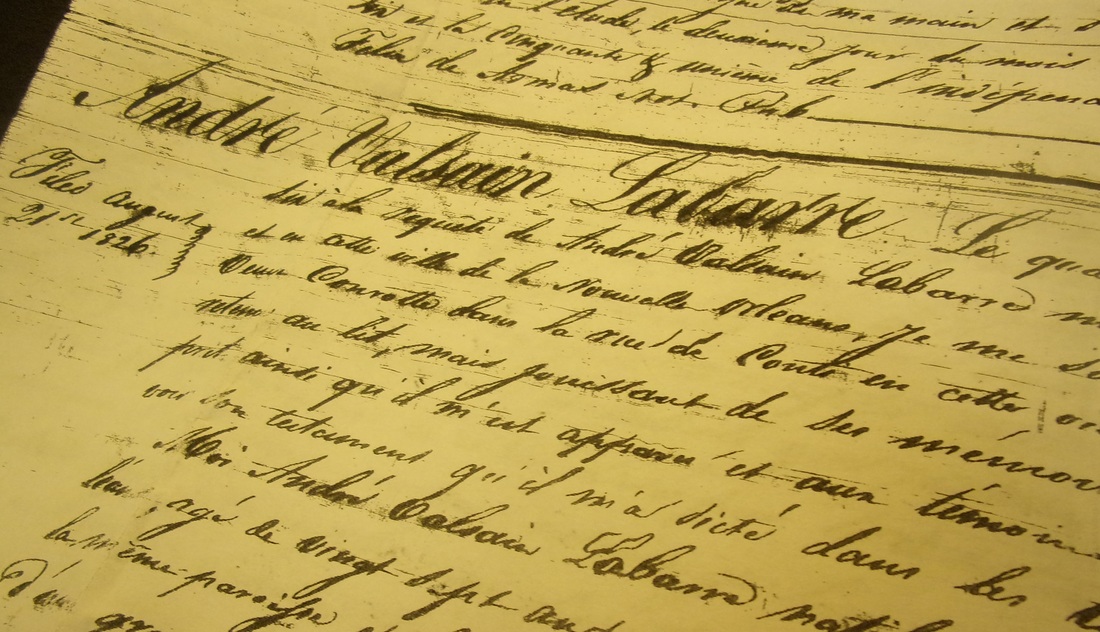

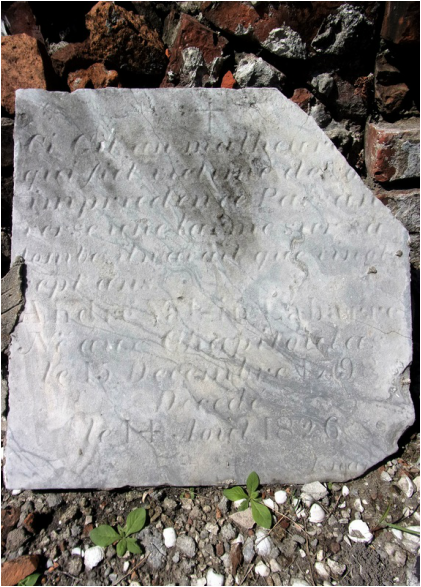

[2] O’Conner, 84-85. [3] “Woodruff and McLeod Monument,” Daily Picayune, March 18, 1855. [4] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 39. [5] “Inauguration of the Equestrian Statue of Andrew Jackson,” Daily Picayune, February 9, 1856, 2. [6] O’Connor, 127. [7] “Firemen’s Charitable Association, Cypress Grove and Greenwood Cemeteries,” Daily Picayune, June 17, 1855; “Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, January 21, 1862. [8] Catherine C. Kahn and Irwin Lachoff, Images of America: The Jewish Community of New Orleans (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 24; The Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, “History of Orthodox Congregations in New Orleans.” http://www.msje.org/history/archive/la/HistoryofOrthodoxCongregations.htm [Accessed September 10, 2017] [9] Barry Stiefel and Emily Ford, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012), 47, 77-80. [10] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 22-23. [11] “Overflow of Canals,” Daily Crescent, October 4, 1860, 1. [12] “The Last Great Flood: Rear of the City Submerged,” New Orleans Republican, June 4, 1871, 1. [13] “Dueling,” New Orleans Republican, May 30, 1868, 3; “To the Common Council of the City of New Orleans,” New Orleans Republican, May 31, 1868. [14] Huber, et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol III: The Cemeteries, 47-48. [15] Ibid. [16] “All Saints Day,” New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1868, 1. Special thanks to Mary Lacoste, author of Death Embraced, for drawing our attention and curiosity to Mr. Labarre. On any given day in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, hundreds of people walk down a back alley toward the “Musicians’ Tomb.” Led by tour guides, they may stop at a newly constructed-tomb or point out a newly-restored one. A few point out the tablet of André Valcin Labarre. One tour guide points to the loose-lying, grey-veined little tablet and states, “He was a bad boy,” as they walk past. The tablet is leaned up against a structure that has likely not been tended for nearly two hundred years. Half-collapsed, it is hardly a tomb any longer. Like uncountable burials in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, it is on its way to becoming completely erased. But Labarre’s tablet remains. Now broken and missing a piece, the Labarre tablet has long been referred to as among the most interesting in the cemetery. Its French inscription is difficult to read, let alone translate, but the words “victime de imprudence” remain visible. These three words have made the tablet a sensation, although nearly all accounts of its message have been incorrect. In a way, this is a story of a man who died young and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. But if this was all there was for André Valsin Labarre we wouldn’t be intrigued by him today. Instead, this is also a story of how one man’s epitaph led to a century of confused transcriptons, translations, and misunderstandings. In the nearly two centuries since his death, he continues to sow imprudence.

From the mid-1700s, the Labarre family owned significant holdings of land in what would become Jefferson Parish. Beginning with Francois Pascalis de Labarre Sr., who served law enforcement and municipal roles, a number of Labarre men claimed the post of sheriff in Jefferson’s early days.[2] Biographers and genealogists refer to the Labarre family as tied to their land, known as Chapitoulas Plantation or the Chapitoulas Coast.[3] The property line for this plantation is still demarked as Labarre Road in Jefferson. The family’s ancestral home, White Hall, is now home to the Magnolia School. André Valsin Labarre (usually addressed as simply Valsin) was born on December 15, 1798 at Chapitoulas Plantation. He is described as having less attachment to the plantation homestead than his parents, siblings, and cousins. According to one genealogist, Valsin was “the first of the Labarre family to move back to the city” of New Orleans since Franscois Pascalis Sr. purchased the Chapitoulas plantation in 1750.[4] Labarre lived in the Faubourg Marigny in 1822, when he married Virginie Conrotte (c. 1808-1850). The two had only one child, Samuel Placide Labarre, born December 4, 1822.[5] As for what André Valsin Labarre could have possibly done to deserve a tablet that suggests he died of his own imprudence, there is no clear answer. As we will see with later interpretations of his tablet, much is up for conjecture. His will shows a fondness for fine possessions: a “big horse of superior quality,” Spanish saddles and riding gear, a double-barreled hunting gun. He also owned five slaves: Fortune (30 years old), Thom (28), Constant (18), Maria (19), and Eliza (15). Thom and Fortune were “carters,” leading some to assume they “operated a cart and sold goods for their master.[6]” Beyond this means of income, it appears Valsin held no definite occupation, suggesting he may have been a man of leisure who enjoyed fine guns and horses.[7] On July 14, 1826, notary Carlile Pollock visited twenty seven year-old André Valsin Labarre at a home on Conti Street, likely the home of a relative.[8] Pollack was called to the house by Virginie Conrotte. Wrote Pollack: on j'ai trouvé le requerant malade retenir au lit, mais jouissant de memoire et entendement naturels, et bien d'esprit “there I found the sick man confined to his bed, but sound of memory and understanding, and in good spirits.” Pollock had been called to compose the last will and testament of André Valsin Labarre. In this will, Labarre named his oldest brother, Francois Pascalis Labarre II, executor and beneficiary of his property. He also requested that his brother care for his widow and son, Samuel Placide Labarre, and see that his son completed proper schooling.[9] No record documents exactly what had caused his illness. Valsin died on Monday, August 14, 1826, one month after writing his will. His obituary in La Courier de Louisiane only confounds the possible cause of his death, but describes him fondly: Mr. Valcin Labarre est décédé Lundi soir, à l'age de 27 ans, a la suite d'une longue et cruelle maladie. Doué d'une excellence constitution et a fleur de l'age, il semblant devoir fournir une longe carriere dans cette vies mais une entiere negligence de lui-meme a donné prise a la fatale maladie qui l'enleva a une nombreuse et respectable famille, a une interessant et jeune espouse, et un enfant en bas age. Mr. L. avait d'excellentes qualites qui le font regretter d'un nombreux cercle d'amis. “Mr. Valcin Labarre died Monday night at the age of 27, following a long and cruel illness. Endowed with an excellent constitution and in the flower of his age, it seemed he should have had a long career in his life, but a complete negligence of himself gave rise to a fatal sickness which swept him away from a large and respectable family, young and caring wife and a small child. Mr. L’s brilliant qualities will be missed by a large circle of friends.”[10] The Epitaph This sense of wasted potential is echoed in the poignant tablet his family erected at his grave. After close study of the tablet, as well as all past transcriptions of it, this is the epitaph carved for André Valsin Labarre:  Ci Gît un malhereux qui fut victime de son imprudence. Passant, verse une larme sur sa tombe, il n’avant que vingt sept ans. André Valsin Labarre Né aux Chapitoulas le 15 Decembre 1798 Decedé le 14 Aout 1826 Here lies an unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Passerby, shed a tear upon his grave, he was only twenty seven years old. André Valsin Labarre Born at Chapitoulas December 15, 1798 Died August 14, 1826 Labarre’s tablet was carved by Jean Jacques Isnard from gray marble. Isnard (1779-1859) was one of the earliest stonecutters in New Orleans. His prolific work can be found throughout St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Valsin’s death and burial in 1826 was the end of a short, but presumably happy life. His cause of death will likely remain a mystery. “Indiscretion or Excess” The phrase “victim of one’s own imprudence,” appears in rather specific narratives in the nineteenth century. It suggests a negligence of self-care by way of excessive living or failure to treat illness in its preliminary stages. For example, a woman who dies of consumption because she did not treat a cold was a victim of her own imprudence. Alternatively, the term “victim of imprudence” was frequently used in advertisements for men who had contracted venereal disease. In the case of Labarre, others have suggested perhaps the excesses of drink, although no record can confirm. For whatever reason, Valsin’s family requested such language for his tablet. Little would they know that the words they paid Isnard to carve would become somewhat of a legend a century later. A Travelling Tablet Perhaps the greatest mystery of all, however, is where Valsin himself was originally buried. A survey completed in the 1930s notes the tablet to be located in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, Aisle 8-R, although it does not specify lot number. Today, Valsin’s tablet is located in Aisle 7-R. Unfortunately, the original cemetery records for 1826 do not specify lot number. While we may love Valsin’s immortal eulogy, his mortal remains may never be located for sure. One Hundred Years of Mistranslation Nearly 75 years after Valsin’s death, in 1900, the New Orleans Daily Picayune wrote a full-page piece on local cemeteries in honor of All Saints’ Day, November 1. This was a common annual occurrence in which newspapers would describe the scene at each cemetery, noting curious epitaphs or beautiful new tombs. With this article, Valsin’s memory was revived in a very peculiar way: On one old slab, almost defaced with age, is the inscription “Ci git un malhereuse qui fut victim de son imprudence. Verse un larme sur sa tombe, et un ‘De Profundis’ s’il vout plait,” por son ame. Il n’avait que 27 ans, 1798.” The translation reads: “Here lies a poor unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Drop a tear on his tomb and say if you please the Psalm, ‘Out of the Depths I Have Cried unto Thee, Oh, Lord’ for his soul. He was only 27 years old.[11] Three years later, on November 2, 1903, the Picayune printed the exact same paragraph in another All Saints’ Day article. This printing birthed two widely-repeated falsehoods regarding Labarre – that he had died in 1798 (the year he was born), and that the tablet had an additional line regarding a psalm, which it clearly does not. This misunderstanding would perpetuate itself, making scholars and authors truly the victims of their own imprudence. In 1919, a tourist brochure said of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1: “The inscriptions are in French, and many of them tell how he who sleeps beneath ‘fell in a duel, the victim of his own imprudence.[12]’” It is unclear if this is directly inspired by Labarre or perhaps another now-missing tablet. Unfortunately, even the most revered of New Orleans cemetery texts replicate to the Labarre myth. In one seminal 1974 book, the authors suggest again that Labarre’s is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, quoting the Picayune article. The text also muses that perhaps the poor fellow had died in a duel. From 1974 to 2004, three other publications cite this faulty article, each suggesting that it is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, and that the deceased had met his end in a duel. One insists that the tablet is long lost to history. All this time, André Valsin Labarre’s tablet has sit idly by as tour groups wind in and out of the cemetery aisles.

New Orleans cemeteries typically identify the owners of tombs by direct lineage. Through this lens, there are no descendants to claim care of the prodigal son’s tablet. Valsin’s son, Samuel Placide Labarre, married Emma Labranche in 1866. Their union produced one son, who Samuel named after his father, Valsin. Valsin Labarre died around 1890. There is no indication that he married or had children. Additionally, Virginia Conrotte remarried after Valsin’s death. She and her new husband, Daniel Gregoire Borduzat had at least four children. Unfortunately, the surname Borduzat appears nowhere in indexed cemetery records. If indirect relatives to Valsin Labarre remain, they have not reconnected with his burial place. Both the tablet to his memory and Valsin himself have become, in a sense, immortal for the most peculiar of reasons. Yet their fate remains suspended between the aisles of New Orleans' oldest cemetery, awaiting the next chapter in their story. [1] Stanley C. Arthur and George Campbell Huchet de Kernion, Old Families of Louisiana (New Orleans: Harmanson, 131), 98-104.

[2] Arthur and Campbell, 98. [3] William Reeves, De La Barre: Life of a French Creole Family in Louisiana (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1980), 79, 88. [4] Reeves, 88. [5] Reeves, 175. [6] Reeves, 119. [7] Probate inventory of André Valsin Labarre, New Orleans Public Library microfilm KR 308, Old Inventories, Vol. L, 1821-1832. [8] 1821 New Orleans directory, Louis Labarre, No. 14 Conti. [9] New Orleans will documents, New Orleans Public Library, VRD410, 1805-1833, Recorder of Wills, Vol. 4, 106. [10] La Courier de Louisiane, August 16, 1826, 2. Accessed via microfilm, New Orleans Public Library. Translation composite of a number of translations from French speakers, William Reeves, and Emily Ford. [11] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1900, 3. [12] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “In Old New Orleans,” from Travel, Vol. XXXII, No. 4 (Feb. 1919), 26. Final part in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. November 1945: six months after victory in Europe and three months since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In New Orleans as much as elsewhere, communities recovered from four years of total war. In the weeks leading up to All Saints’ Day, preparations for those who died overseas was a topic of discussion. Many of these soldiers would not come home at all. The American Battle Monuments Commission, which had been founded in 1923, would establish fifteen foreign monuments and cemeteries in Europe, the Pacific, and Tunisia to memorialize fallen soldiers. In April of 1945, the war department announced 5,335,500 newly available burial plots in 79 existing and new cemeteries.[1] This number seems enormous until we remember that 16.1 million Americans served in World War II. About 300,000 died in service.

As early as mid-October 1945, hardware stores advertised items specifically for tomb care, including “Rock-Tite cement paint, which…is waterproof, tends to seal tomb corners, and lasts for years.” In many cases these materials were ultimately harmful to soft lime-stucco and brick tombs. Yet 1945 heralded a long (and ongoing) boom of new, strong, and user-friendly materials that would widely be seen in New Orleans cemeteries. This technological and cultural boom contrasted with some of the oldest cemeteries in the city, which were seen as outdated and, at worst, nuisances. Such was the case for Girod Street Cemetery. The Protestant cemetery, founded in 1822, had long been considered an eyesore. As early as the 1880s, the state government of Louisiana considered closing the low-lying cemetery altogether. By the 1940s, its condition was such that cemetery authorities took action. In 1945, officials at Christ Church Cathedral conducted a survey of Girod Street – “the first Protestant burial ground in the Lower Mississippi Valley" – and concluded that “some 1000 of the old vaults and tombs in which many of the city’s prominent and wealthy families were buried are a menace to public health.[4]” Each of these vaults and tombs was marked on All Saints’ Day 1945, and posted with a notice to families that the tombs must be repaired within 60 days. If no action was taken, said the city public health department, the tombs must be demolished. Reports from the sexton of Girod Street Cemetery suggested that as many as forty families did respond to the notices. However, it was too late for Girod Street Cemetery. The burial ground was deconsecrated in 1957 and demolished. The remains of white bodies were re-interred in Hope Mausoleum, and burials of African Americans were interred at Providence Memorial Park. [1] “Move to Return War Dead Begun,” Times-Picayune, April 5, 1945, 27.

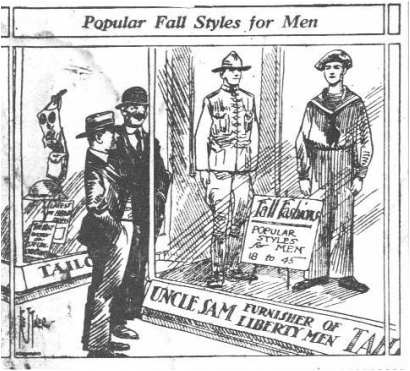

[2] “Orleanians Plan Halloween Observance in Usual Style,” Times-Picayune, October 31, 1945, 4. [3] “Up and Down the Street,” Times-Picayune, October 11, 1945, 34. [4] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945, 12; “Girod Cemetery Inspected,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945, 5. Fourth in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. New Orleans, along with the rest of the United States, was at war. The drafts of 1917 and 1918 would send a total of 71,000 officers and enlisted men from Louisiana to Europe to fight in World War I. On the home front, military installations were built, war bonds were purchased, and the economy boomed to meet new agricultural and industrial demands. In May 1918, Berlin Street in New Orleans was re-named General Pershing as a patriotic gesture.[1] Although many of the dark realities of trench warfare in Europe had yet to touch New Orleaneans, some families had already felt the pain of loss. Grayson Hewitt Brown, only nineteen years old, was stationed at Camp Beauregard near Pineville. A volunteer to the 141st Field Artillery, Brown assisted health care workers during an outbreak of spinal meningitis by carrying a stricken comrade out of the camp. Days later he died of the same disease. His parents buried him in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 along the main aisle with the epitaph, “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends.[2]” But the Great War was only one of two world-wide battles in 1918. The great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 swept across the globe in three waves, the most pronounced of which had only begun to wane by November. Indeed, many of the young men drafted to the military in this year died of influenza before even reaching the trenches. Such was the case for Henry Philip Walter Rathke, not even 26 years old, who died in naval service in New York prior to deploying. He was also buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; he left a widow and a young daughter.[3]

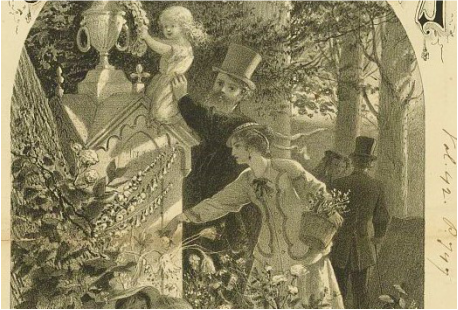

Supply of the flowers had been thinned already by families mourning those died of influenza. By late October, chrysanthemums were advertised at $6 to $9 – $100 to $150 in present-day dollars – and sold at twice the price of roses.[5] The chrysanthemum blight was front page news, and florists noted that customers were purchasing red roses and dahlias, as opposed to the usual “dead white.” In the next year, a third and final wave of influenza would cross the United States, as Louisiana’s enlisted men returned home from war. In 1921, a bronze flagpole was erected in Audubon Park to commemorate New Orleans Great War veterans. Yet the commemoration of those lost to war and influenza took place also in the decoration of graves on All Saints’ Days in years to come.  "The floral world will not be outdone by human beings, it would appear, and is plunged in the midst of one of the most widespread outbreaks of disease in history of local greenhouses... following out the example of human beings as closely as possible," from the Times-Picayune, Oct. 27, 1918. Image Dodd, Mead and Company - New International Encyclopedia (1923), Wikimedia Commons. [1] The Weekly Iberian, May 11, 1918, 4.

[2] “Grayson H. Brown Dies at Beauregard,” Times-Picayune, January 19, 1918, p. 11; “Armory Fund Gets Soldier’s Earnings,” Times-Picayune, August 24, 1918. [3] http://www.rainedin.net/silbern/i11310.htm [4] Natchitoches Enterprise, October 31, 1918, 3; Times Picayune, November 1, 1918, 10; St. Martinsville Weekly Messenger, October 26, 1918, 2. [5] Advertisement of Frank J. Reyes, florist, 525 Canal Street, Times-Picayune, October 20, 1918, 2; “Blight Attacks Chrysanthemum Crop of the City,” Times-Picayune, October 27, 1918, 1. The third in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. 23,707 infected. Not less than 4,600 dead. Such was the toll of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 in New Orleans. The Crescent City was ground zero – the first point of contact in the United States for an epidemic that swelled north and eastward from July through November, taking 20,000 souls in total. Dozens of burials in each cemetery each day led one report to state that, in a sense, each day of the summer of 1878 had been All Saints’ Day. On the day of the holiday itself, many graves still retained the decorations of burial.[1] And the epidemic was not even completely over.

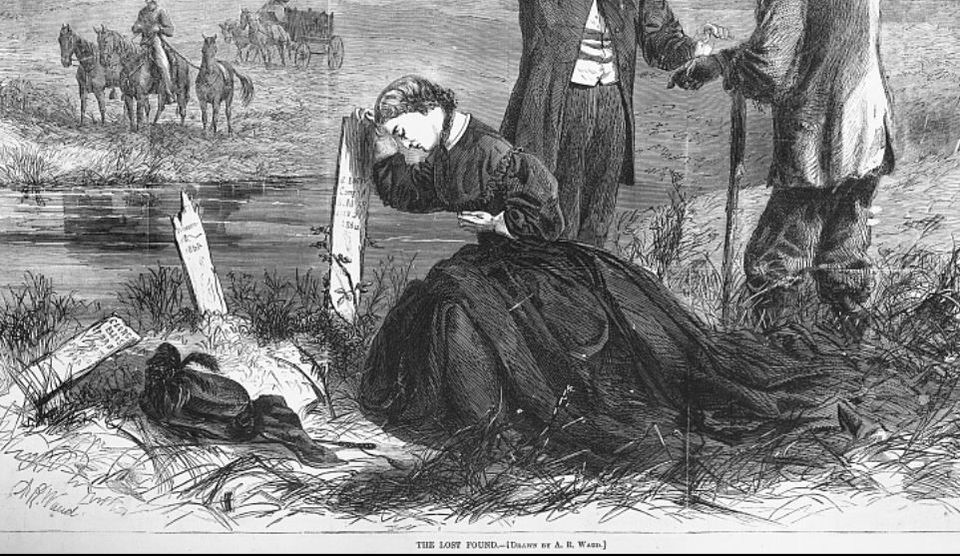

In the days leading up to All Saints’ Day, some health officials even cautioned against the yearly tradition of decorating and caring for loved ones’ graves. Said the Daily Picayune: It should be mentioned… that some physicians are of the opinion that, owing to the extraordinary number of interments during the summer and the prevalence of infectious disease, it would not be safe for a general decking of graves to be carried out as on occasions of the past.[2] The second in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. Need we say whose graves they were? Need we say whose fair hands placed those mementoes there, or whose kind hearts prompted the deed? On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, ending the Civil War. In New Orleans, infrastructure and economy lay in ruin. By November, the observance of All Saints’ Day was fundamentally changed from antebellum celebrations – in fact, the way all Americans interacted with death had changed forever. In general, nineteenth century Western culture was marked by an intimacy with death that would be incomprehensible to most modern-day people. Understanding that death could be swift and sudden, each person hoped only for a “good death” – one in which last words could be uttered, surrounded by loved ones. This ideal was sought even among soldiers, who kept letters in their pockets in case of their death, or who wrote such letters for dying friends. Yet the horrific realities of war – and the bad death that was its companion – were unavoidable. Advances in technology led to extensive photographs of Civil War battlefields, exposing civilians to the carnage of the conflict, and “stripping away much of the Victorian-era romance around warfare.”

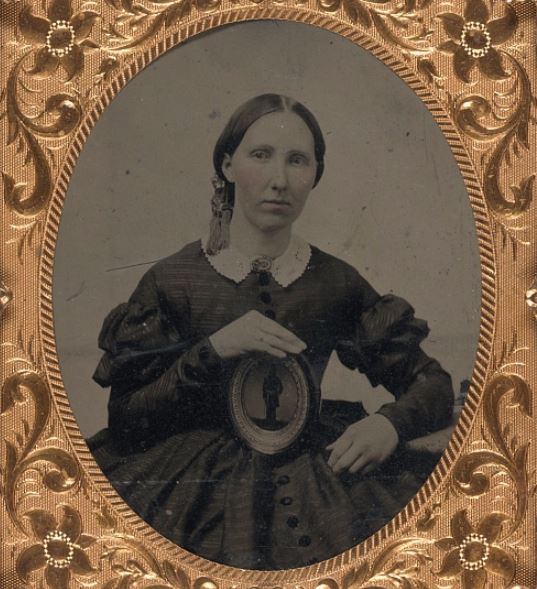

The destruction of the Southern economy in 1865 and 1866 is unlike anything any Americans ever experienced at any other time, at least on our home soil. The writers from Northern newspapers and magazines who went South after the war end up observing open coffins laying all over the place at cemeteries. They end up seeing old men and former slaves going around collecting bones because they could get a dollar for so many pounds of bones off battlefields. Those are the bones of men who died -- without a name, a place, they were never sent back to their families. This is what people would see if they went to those battlefields in 1865 and 1866 -- and for that matter for many years afterward. Most of the Civil War cemetery monuments we know today – the Confederate Army of the Tennessee and Army of Northern Virginia monuments, the Confederate monument at Greenwood Cemetery, the Grand Army of the Republic monument at Chalmette National Cemetery – were not erected until the 1870s and 1880s. In the years between Appomattox and the first official Memorial Day in 1868, efforts by Clara Barton and others to identify and re-locate fallen soldiers on both sides of the conflict resulted in the disinterment and reburial of thousands in New Orleans alone. However, this process would take years. On November 1, 1865, a great many of those who would come home were not yet located or reburied. Documents state that it was a beautiful Wednesday of extremely pleasant weather. Among the notable architecture newspapers chose to highlight in this year were the tomb of the New Lusitanos Benevolent Association and the tomb of W.W.S. Bliss, both located in now-demolished Girod Street Cemetery. They also noted the then-burial site of Albert Sidney Johnston in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. General Johnston was later re-interred in Texas: Several soldiers in tattered gray stood around. “You served under him,” we remarked to one, as we looked at him. Tears started in his eyes as he merely said, “yes,” and pulled a twig from a cedar circlet, hanging on the grave, and handed it to us. Other articles point out the noticeable presence of many more male attendees to ceremonies than in years past. Yet the focus of the holiday in 1865 seemed to be on the women – mothers and spouses who mourned lost soldiers. The Lusitanos tomb is described as attended by wailing women. In another account, women tend to the simple wooden monuments that temporarily marked their loved ones’ resting places: …we came upon a number of graves, very plain and unpretending, with but a wooden foot and head board… Not one was left undecorated – not a single one without a flower, a bouquet, or a wreath to mark that some kind, gentle, amiable feminine heart had stood there to tender a memento to departed valor. Need we say whose graves they were? Need we say whose fair hands placed those mementoes there, or whose kind hearts prompted the deed? They were the same heroic women of our city who, with noiseless step and sad, earnest eye, have treaded the avenues of the hospitals during the last four years, in search of the wounded and dying soldiers… Ten of them had assembled under a lofty oak… and spent almost the entire day in preparing wreaths and decorating those humble graves. Sources:

PBS American Experience: Death and the Civil War “The City,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1862, 1. Army of Northern Virginia tomb erected 1881; Army of the Tennessee tumulus erected 1887; Confederate Monument at Greenwood Cemetery, remains relocated 1868, monument erected 1872; Grand Army of the Republic monument completed 1883. “The City,” Daily Picayune, November 1, 1865, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1865, 1. Daily Picayune, November 5, 1865, 1. First in a five-part series of All Saints' Day through New Orleans history New Orleans heritage is steeped in holidays and celebrations. Amidst the hedonism and mystic antics of Mardi Gras, Twelfth Night, and other festivals is the contrasting solemnity of All Saints’ Day. Part of the Catholic calendar since the fifth century, All Saints’ Day (also known as the Feast of All Saints, Hallowmas, and All Hallows) has its origins in Roman, Germanic, and Celtic celebrations seated in prehistory. Today it is celebrated on November 1, although some Eastern Orthodox and Protestant denominations celebrate it on the first Sunday of November. The feast day began as a holy day in which the lives of the Catholic Saints were remembered and honored. However by the time of the arrival of French and Spanish colonists to New Orleans, the day rather signified the recognition of all saints, “known and unknown,” and more generally the remembrance and communal mourning of the dead by their survivors. By 1853, the oldest above-ground cemetery in New Orleans (St. Louis Cemetery No. 1) was 65 years old, and the imported traditions of above-ground burial and observance of All Saints’s Day enjoyed great significance in the rituals of the Catholic and Protestant communities. From the Catholic St. Louis Cemeteries to Protestant Girod Street, municipal Lafayette, and fraternal Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows’ Rest, the day was observed and reported on – not only as a day of mourning, but one of cultural spectacle, high style, and great charitable expectations.

From the numerous complaints made this morning of the careless manner in which the coffins containing dead bodies are left at the Fourth District cemeteries, it would appear that there are not enough hands employed there to bury the dead. The hearses bringing them place the coffins at the gate of the cemetery, and there, it is stated, numbers of them remain for hours, and in some cases all day and all night, the effluvia given forth reaching houses four and five squares off. … it is a sad enough necessity that we should live in the midst of an unsparing epidemic… But it should be the last reproach a city should receive, that she cannot bury her dead decently and respectably, in accordance with the feelings in which every human being participates.

The devastation of the epidemic lay not only in the cemeteries, but ever more so in the homes for widows and orphans. Benevolent associations, the members of which were bonded by nationality, profession, or religion, incorporated into All Saints’ Day a tradition of charity in which the orphans of various asylums would be present in the cemetery, collecting alms to support their care. Among these asylums was that of the Catholic orphan boys of the Third District, which cared for 300 children in October of 1853, and predicted another 100 within the next month. This institution, among others, stood present at the Catholic cemeteries on November 1, hoping for enough donations to build a new wing to accommodate their new charges.

The Daily Crescent describes a day of crowded cemetery avenues and people of all ages, “singularities of every hue, and representing every nationality… not before midnight were the decorations complete. It was then that thousand tapers and waxen lights everywhere covering the tombs were lit up, and a light flashed over the scene, imparting to it an almost magical brilliancy.” Said one author to the editors of the Baton Rouge Daily Comet of New Orleans’ All Saints’ Day observance: "Now, however, I am so much of a Catholic that I like all Saints day [sic] – I am in favor of the custom of making an annual pilgrimage to the graves of those we loved in life…” this author, signed only as “L,” describes the throngs of people, the “gaudy” decorations, the invocations of beautiful hymns. Yet the pall of epidemic’s devastation burns through even the most endearing recollections of All Saints’ Day 1853. “L.” concludes his letter not with the solemnity of honoring the dead, but with the discussion of the recent suicide of a New Orleans lawyer: He was buried on Sunday [October 30] followed to the grave by a large number of citizens. While the long cortege of carriages which followed his remains were passing slowly down the street to the Protestant Cemetery, another funeral came dashing along Hevia Street [now Lafayette Street], followed by a half dozen empty carriages, and all driven at a smart trot, as if in a hurry to get the dead out of sight as soon as possible. The latter procession had just time to cross the path of the former ere it came up making a forcible contrast in appearance and character between the two. One was a rich man going to lay down in his last resting place, the other was a poor stranger hurried to his final bed. When earth has reclaimed what was of her, who will be able to distinguish the ashes of the one from the other? Sources:

Walter Farquhar Hook, A Church Dictionary (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1852), 16. “Burying the Dead,” Daily Picayune, August 8, 1853, 1. “Female Orphan Asylum,” Daily Picayune, October 23, 1853, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 28, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 31, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, November 2, 1853, 1. “Correspondences,” Baton Rouge Weekly Comet, November 6, 1853, 1. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

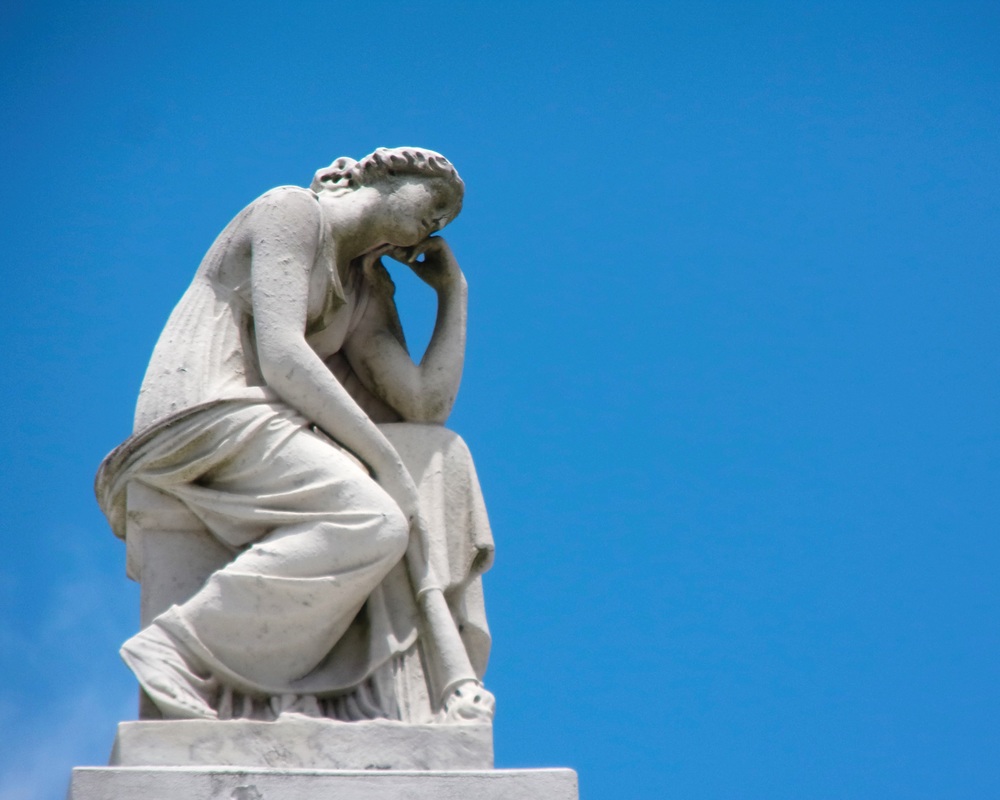

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly