|

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Throughout the course of the nineteenth century, the New Orleans Jewish experience varied among individuals and families, from great successes to great defeats. For some, it was something one was born into: by mid-century, a number of families had developed deep roots in New Orleans commerce and culture. For men like Judah P. Benjamin and other merchants, lawyers, and factors, New Orleans was a place of opportunity among aristocrats and politicians. For others, however, New Orleans was a refuge, only slightly improved from the poverty and exclusion of the homeland from which they had fled. Among the Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who immigrated to New Orleans between 1840 and 1880, many found their new home to be wracked by destitution, disease, and an uncertain future. These immigrants formed their own communities, establishing a familiar cultural norm to ease their transition in the New World.[1] Two New Orleans stonecutters exemplify this wide spectrum of experience. Edwin I. Kursheedt, part of an influential Jewish family, was successful not only professionally but personally. Committed to charity and military service, he inherited his business from his father and carried it into the twentieth century. Alternatively, the carved signature of H. Lowenstein is nearly all that remains of this stonecutter’s legacy. It is likely that his time in New Orleans was brief, cut short by disease, war, or the search for better opportunities.

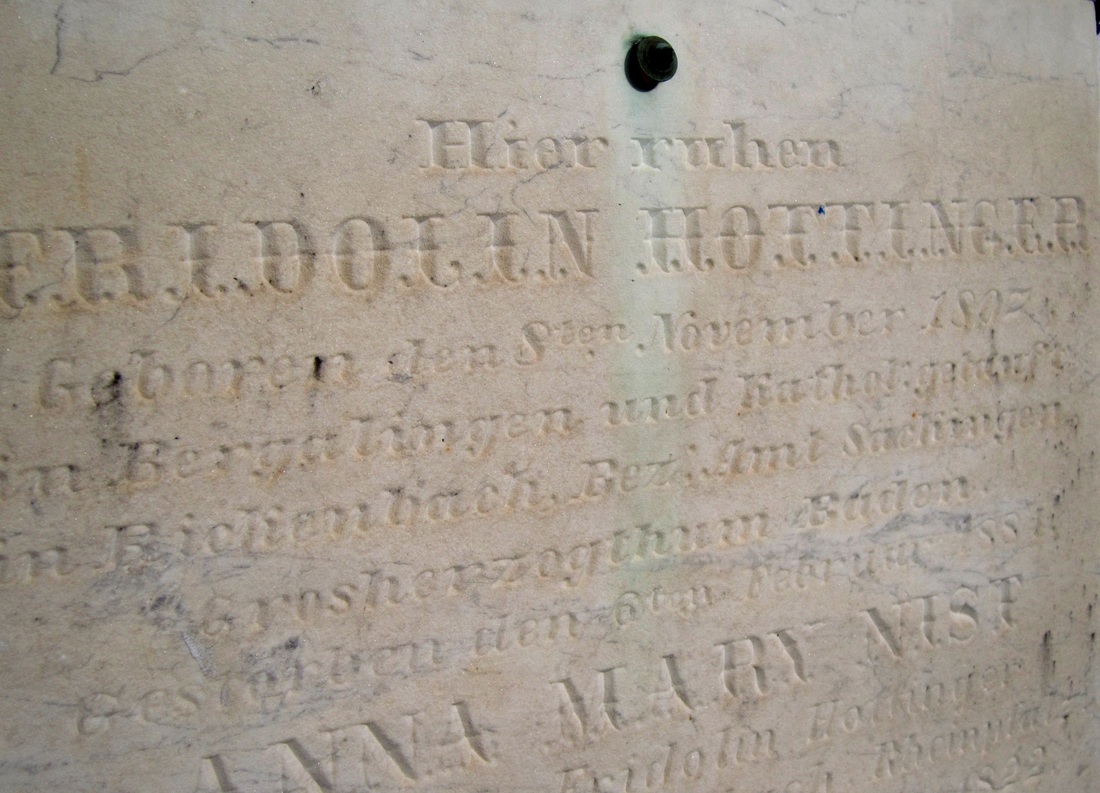

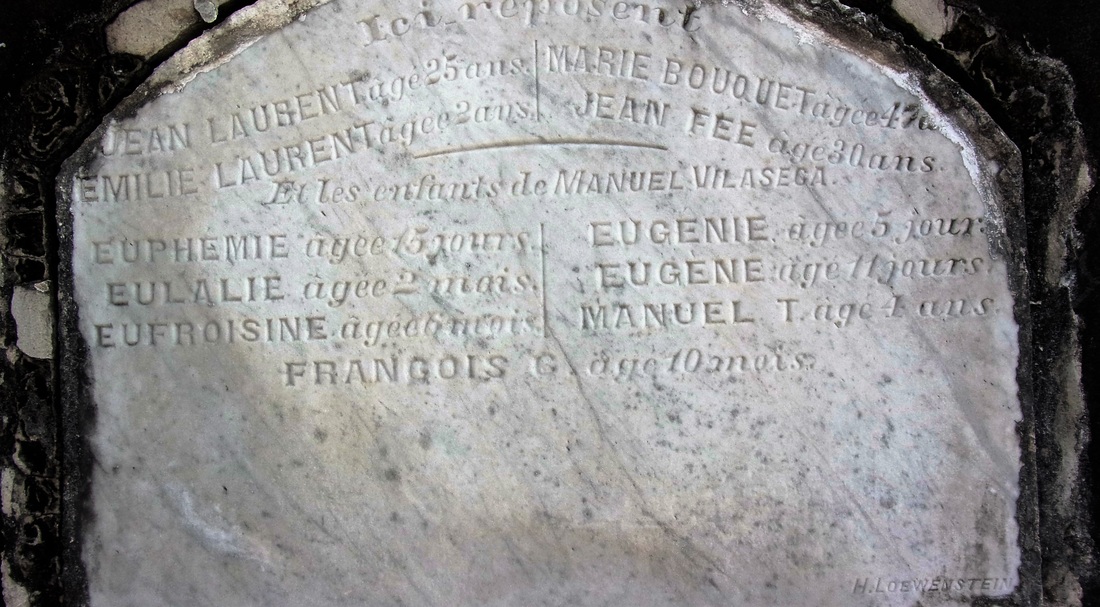

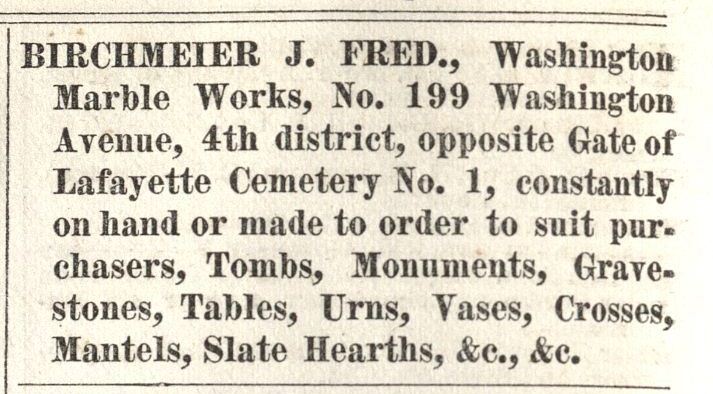

The address of H. Lowenstein’s business is recorded in directories and on his signed tablets as 195 and 197 Washington Avenue, which corresponds to the historic marble yard and shop located across Washington Avenue from Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. During the years Lowenstein held business there, other stonecutters and sextons advertised at the address, namely James Hagan and Philip Harty. Lowenstein also advertised himself as an undertaker at this address. Lowenstein’s carving style bears a resemblance to that of other contemporary German stonecutters, namely the Anthony Barret and his sons Charles and Frederick. These artisans carved in the German Fraktur style, or black-letter, and employed similar imagery of oak and laurel wreaths that are not found among the work of non-German craftsmen in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. These scant traces of Lowenstein in New Orleans indicate that he was likely a German-Jewish immigrant who served the community of the Fourth District, once part of the suburb of Lafayette. A number of German newspapers, including the Deutsche Zeitung and the Louisiana Straatszeitung, may have been the venue for his advertising. Considering he frequently carved closure tablets in German, it is likely that he aided more established craftsmen like Hagan and Harty with their business in the German immigrant community. Yet, after 1869, documentation of H. Lowenstein evaporates completely, suggesting that, like many other Jewish immigrants in the South, he may have moved elsewhere, or possibly died young in New Orleans.

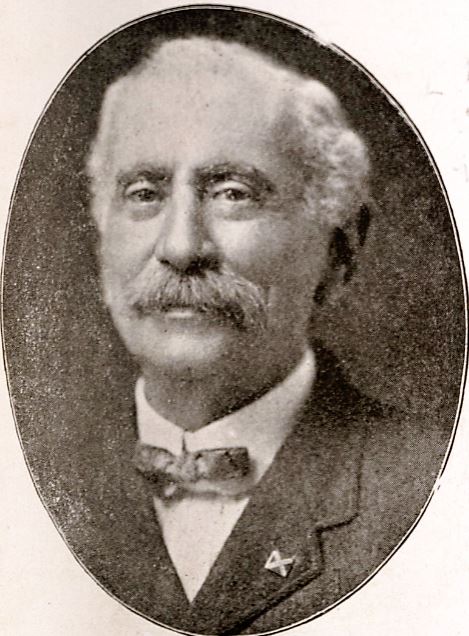

The business of Kursheedt & Bienvenu was among the most successful and prominent merchants of not only cemetery stonework and tombs but also hardware, commercial stonework, mantels, grates, and other items. By the 1880s, they owned not only a large show room on Camp Street but also a marble yard next door, at which at least thirty men were employed.

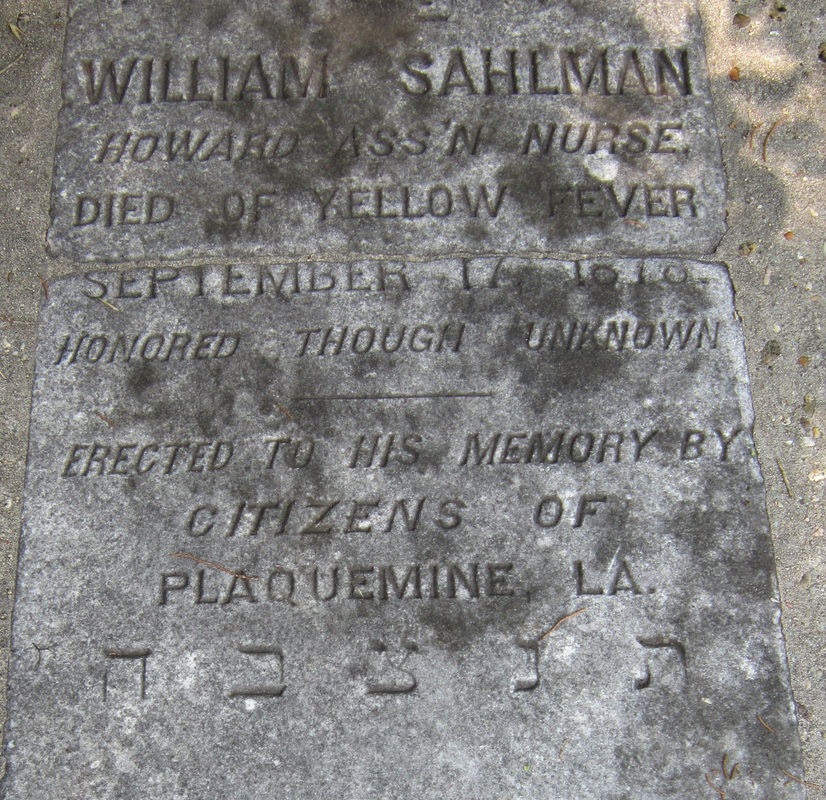

Much of Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s signed work can be found in Jewish cemeteries in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Alexandria, and Plaquemine, among other Louisiana towns. Within Jewish cemeteries, this work consists of headstones, as Jewish tradition prohibits above-ground burial. Yet Kursheedt & Bienvenu served clients of all religions and traditions. Among their most visible commissioned works is the Sercy tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Marked by a stone sarcophagus and located near the Washington Avenue cemetery gate, it is most notable for its epitaph: “Died of Yellow Fever,” a relic of the 1878 epidemic. J.G. Bienvenu left the business after 1888, and Edwin Kursheedt operated Kursheedt’s Marble Works until 1901.[8] Throughout these years, he served on various boards for Jewish Charities, including Touro Infirmary, the Hebrew Benevolent Association, and the Jewish Widows and Orphans Home.[9] He died in on February 21, 1906, at the age of sixty-seven, a veteran, merchant, benefactor, husband and father. He is buried in Dispersed of Judah Cemetery on Canal Street. It is unclear where or when H. Lowenstein died. The only tenuous hint points to an obituary published in the New Orleans Daily Picayune November 3, 1896, reporting the death of Henry Lowenstein, who died at the age of fifty-six in Cincinnati, Ohio. That a New Orleans newspaper reported his death suggests he once lived in the city, and may have been a young stonecarver on Washington Street in 1861, but no definitive documentation can support this possibility.[10] So these two artisans whose work is marked in New Orleans cemeteries died as they lived: one documented and memorialized, one lost in historic thin air, as were many immigrants who came and went from the Crescent City in the nineteenth century. [1] Bobbie Malone, “New Orleans Uptown Jewish Immigrants: The Community of Congregation Gates of Prayer,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 32, No. 3, Summer 1991, 239-287; Ellen C. Merrill, Germans of Louisiana (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2005), 225, 236.

[2] The signature “Löwenstein” can be found on the Fridolin Hottinger tomb, Quadrant 2, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1861 (New Orleans: Charles Gardner, 1861), 282; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1866 (New Orleans: True Delta Book and Job Office, 1866), 279; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1869 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1868), 399. [3] Bertram Wallace Korn, The Early Jews of New Orleans (American Jewish Historical Society: 1969), 247-249; “Mr. Israel Baer Kursheedt,” The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, Vol. X, No. 3, June 1852, 1. [4] Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 111-116. [5] Andrew Morrison, The industries of New Orleans: her rank, resources, advantages, trade, commerce and manufactures, conditions of the past, present and future, representative industrial institutions, etc. (New Orleans: J.M. Elstner & Co., 1885), 144. [6] Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 21, 1880, 5; “The Other Side: The Report Adopted by the State-House Commission Respecting the Work Done,” Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 28, 1880. [7] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1887 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishers, 1887), 513. [8] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1889 (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1889), 532; Soards’ New Orleans City Directory, for 1901, Vol XXVIII (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1901), 501. [9] W.E. Myers, The Israelites of Louisiana: Their Religious, Civic, Charitable and Patriotic Life (New Orleans: W.E. Myers, 1904), 103. [10] Daily Picayune, November 3, 1896, 4. See also, Emily Ford and Barry Stiefel, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (History Press, 2012).

5 Comments

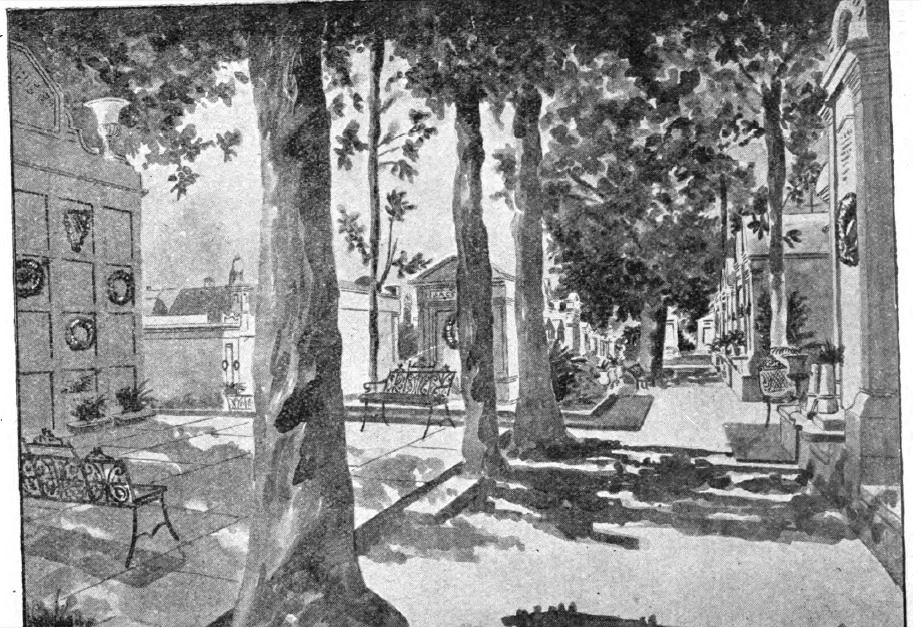

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. Full text here: http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/ The history of sextonship in New Orleans is as old as the city’s cemeteries. The origin of the cemetery sexton derived from European tradition, in which the sexton would care not only for the graveyard surrounding a church sanctuary, but also for the church itself. In New Orleans, the first sextons likely were part of a lay ministry, employed by the Catholic Church to care for St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and, later Saint Louis No. 2. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, however, was not administered by the Church or any other religious group. Instead, it was established in 1833 by the municipality of Lafayette, a suburb of New Orleans. Translating from the ecclesiastical to the secular sphere, the City of Lafayette employed a sexton to care for the cemetery at Washington Avenue and Prytania Street. From the cemetery’s founding into the 1950s, at least twenty-two individuals served as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Many were stonecutters and tomb builders, some were additionally undertakers, politicians, and masons. They cared for the cemetery in times of epidemic, vandalism, and population shifts. Through their stewardship, the landscape of the cemetery was formed. Phil Harty and the First Sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 Up to and after the City of Lafayette was incorporated into the City of New Orleans in 1852, the role of the sexton was to perform and record interments, submit interment records to the city council, and maintain the cemetery grounds. It was also his responsibility to enforce the ordinances of the city and state regarding interments and sanitary conditions.[1] These laws included the collection of a certificate of burial (presented by a physician or coroner to the deceased’s family), ensuring the deceased was properly placed in a coffin, and construction regulations regarding tombs. Failure to perform these duties resulted in punishment from City Council.[2] Sextons were additionally paid a fee for each interment based on the deceased’s status as colored or white, child or adult, and whether the interment was to be an act of charity. In the nineteenth century, these fees varied from 50 cents to $1.50, with a $3.00 charge for the opening and closing of tombs and vaults, to be paid by the owner.[3] The first sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was most likely B.S. Quinman, who served from 1832 to 1844.[4] After Quinman, H.G. Hicks served briefly in the position. While many sextons constructed tombs in Lafayette No. 1, no structure or tablet in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 bears either man’s signature. Their successor, however, seems to have made more of an impact on the cemetery. Philip Harty, mostly referred to in documentation as Phil Harty, served as Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 sexton from 1855 to 1861. [5] Only one of his signed works survive amidst the rows and aisles of tombs: the tomb of A. Thomas, located near the rear gate.[6] He lived at 197 Washington Street, across from the main gate of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. This address was utilized by numerous sextons and stonecutters throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Today, the lot is listed as 1427 Washington Avenue. The building is currently utilized as the administrative offices for Commander’s Palace restaurant. Phil Harty died August 14, 1861. His obituary, describing his death as “sudden,” states that Harty was well-known as a sexton and a “hearty, merry fellow up to the very hour of his death. Thousands he has introduced to the narrow house, and now he has gone himself, with scarcely a moment’s warning.”[7] D.F. Simpson, a local stonecutter, followed Harty as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1863 to 1868. He was also a stonecutter and tomb builder – his office was located on Race Street.[8] Examples of his work remain in the cemetery today, including the Stearns tomb and at least three constructed while Simpson was in business with later sexton J. Frederick Birchmeier. Following D.F. Simpson were James Hagan (1830-1908, sexton 1865-1867), and Joseph F. Callico (sexton 1867-1875).[9] James Hagan served as state senator representing Orleans Parish from 1880 to 1884. Based on remaining signed tombs and closure tablets, J.F. Callico was one of the most prolific stonecutters among the sextons of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1: today, nearly thirty tablets in the cemetery bear his signature. 1865 – 1900: A Thriving Craft Community The late 1870s were unusual for the stewards of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in that no one individual served for more than a few years. As had occurred in previous years, especially 1853, yellow fever epidemics were particularly difficult times for sextons. It is possible, then, that the 1878 epidemic, the marks of which are still very visible on the tombs and tablets of Lafayette No. 1, caused an upset in the administration of the cemetery. In quick succession, Dennis Irvin, Cornelius Donovan, John Barret and Patrick Gallagher served as sextons from 1876 to 1880. Patrick Gallagher likely left his office due to accusations against him that he attempted blackmail on an unnamed person.[10] After these men, J. Frederick Birchmeier, a stonecutter who had been active in Lafayette No. 1 for decades, became sexton.[11]

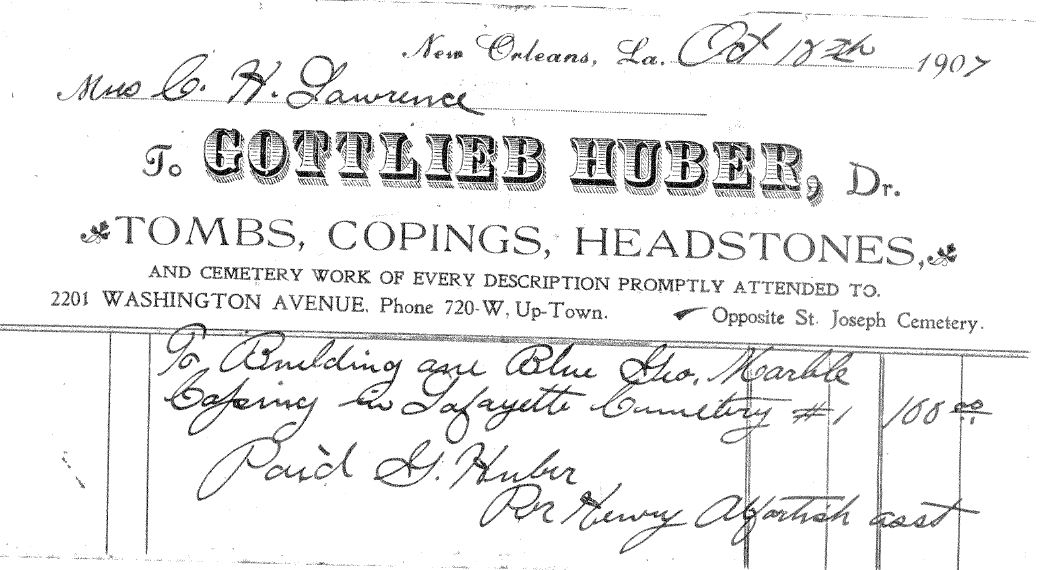

The turn of the twentieth century brought to Lafayette No. 1 a close-knit community of stonecutters and tomb builders, many of whom served as sextons. After J. Frederick Birchmeier retired, his colleague Hugh J. McDonald (1853-1895, sexton 1886-1895) took over stewardship of the cemetery. After McDonald’s death, stonecutter Charles Badger succeeded him. Badger was also the husband of Birchmeier’s daughter, Margaret.[14] Both Badger and McDonald were close colleagues of Gottlieb Huber, who was sexton from 1902 to 1915. The legacy of this community would continue for the next thirty years through another young protégée of these men. 1900 – 1945: The Alfortishes In 1911, Henry Alfortish became assistant to Gottlieb Huber at Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Alfortish also worked with Huber privately, and would absorb Huber’s business after his death in 1926.[15] The influence of Alfortish and, later, his son Edward, would greatly change the cemetery. In the 1920s, Alfortish declared numerous lots abandoned and “open for sale.” He sold these lots and tombs to new clients and, additionally, provided replacement deeds for families who had lost their tomb ownership documents. It was also under the sextonship of Henry Alfortish that the wall vaults once located along Sixth Street were cleared and demolished. Numerous coping tombs located along this wall today bear Alfortish’s signature.[16] Edward Alfortish assumed sextonship of Lafayette No. 1 in 1942. However, the role of sexton was no longer seen as relevant in the city-owned cemetery. Few burials were made compared to the heyday of Lafayette No. 1, and many of the responsibilities of sexton could be carried out by other city officials. By around 1950, no individual would serve as sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 again. The caretakers of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, from 1833 to 1950, built the cemetery as it is seen today. They designed and constructed its tombs, removed and replaced landscape features, fostered its dead and their families, and protected the cemetery from harm. Their names are placed alongside the names of Lafayette No. 1’s most famous residents, in the form of carved signatures at the bases of closure tablets and headstones. The story of this National Historic Landmark cemetery is very much their story. [1] “Ordinance Relating to Cemeteries and Interments,” Daily Creole, December 30, 1856, 4; State of Louisiana, The Revised Statutes of Louisiana (J. Claiborne, 1853), 386.

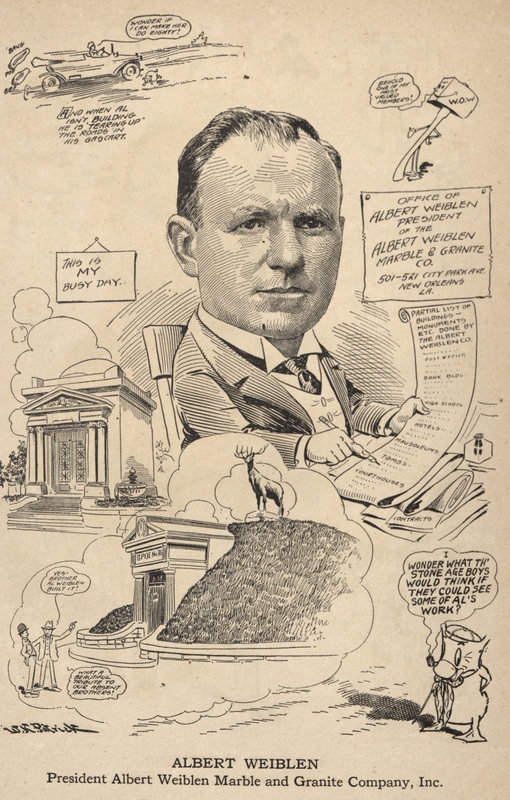

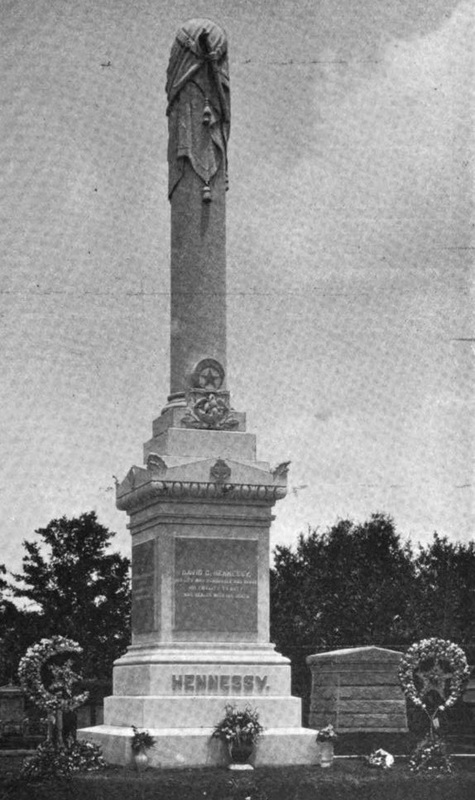

[2] “City Intelligence: Board of Health,” Daily Picayune, August 4, 1853, 1. [3] Ibid.; Currency evaluation oriented around historic standards of living, these costs equate to approximately $20-$40 per interment and $81 (2011 dollars) for the opening/closing of a tomb or vault. (www.measuringworth.com) [4] Louisiana State Board of Health, Biennial Report of the Louisiana State Board of Health, 1883-84 (Baton Rouge: Leon Jastremski, 1884), 40. [5] Daily Picayune, February 15, 1855, 6; Mygatt & Co.’s Directory for New Orleans, 1857, W.H. Rainey Compiler. L. Pessou & B. Simon Lithographers, 23 Royal Street, New Orleans, 1857, 49; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for the Year 1859 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1858), 377; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1860 (New Orleans: Bulletin Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1859), xvi. [6] Based on a 2012 survey of all signed craftwork in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. The Isaac Bogart tomb, located in Quadrant Three of Lafayette No. 1, is documented in the 1981 Save Our Cemeteries/Historic New Orleans Collection Survey of Historic Cemeteries as having a tablet signed by Phil Harty. The tablet has since been lost. [7] “Sudden Death,” Daily True Delta, August 15, 1861, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 18, 1866, 3. [9] Based on directories and municipal documents. [10] “An Official Suspended,” Daily Picayune, October 9, 1878, page 2. [11] Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1880 (New Orleans: L. Soard’s Publishing Co., 1880), 456; Soard’s New Orleans City Directory for 1882 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1882), 142; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1883 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishing, 1883), 452. [12] “A Singular Case,” Daily Picayune, June 14, 1868. [13] Receipt from J. Frederick Birchmeier to the widow of John Paul, Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 365. [14] Daily Picayune, February 8, 1891, 1. [15] Times-Picayune, January 20, 1926, 2. [16] Receipts for lots Quadrant Three, Lots 16 and 17, Quadrant 1, Lots 270-275, the Moulin, Gonea, Legien, and Bittenbring tombs. Sexton’s book, page 127. Historic New Orleans Collection, Leonard Victor Huber Collection, MSS 365. On May 1, 1957, and only a few months shy of his 100th birthday, Albert Weiblen passed away in New Orleans. In his lifetime, Albert Weiblen was a revolutionary figure in New Orleans cemetery architecture. Under his carving hand, the craft of tomb building would expand from a hyper-local, individual cottage profession into a modern industry – spanning the eastern United States and powerfully altering the landscape of New Orleans cemeteries. A German Immigrant in New Orleans Albert Weiblen was born in 1857 in Metzingen, Wurttemberg, Germany. Sources suggest that he began his work as a sculptor in his homeland, apprenticing in the manner that was traditional for the time.[1] Weiblen immigrated to the United States in 1883 and soon afterward began work with local marble company Kursheedt and Bienvenu. Operational from 1867 to 1901, the company was co-owned by Edwin I. Kursheedt, a prolific stonecutter in his own right who, in addition to work in New Orleans’ Jewish cemeteries and other cemetery stonework, supplied the stone for the reconstruction of the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the late 1880s.[2] At this time, New Orleans’ cemetery stonecutting industry was already changing. The florid, individualized Classical-revival tombs popular from the 1840s through the 1860s had given way not only to new styles inspired by Gothic and Italianate revival aesthetics, but also to economies of scale. The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878 galvanized this trend. In this year, the construction of tombs shifted more to “cookie cutter” and slightly simplified styles, replicated by numerous carvers and builders.[3] Weiblen stepped into the cemetery craft scene in New Orleans at a time when this streamlining of tomb construction was in its infancy. New industrial technology, such as saws and machinery to cut granite and marble, new types of stronger hydraulic cements, and stonecutting technology powered by pneumatic chisels and even sandblasting, had been adopted elsewhere in the country, but were a long way off from making their debut in New Orleans cemeteries.[4] When these new tools and methods did arrive, though, it was often Weiblen who spearheaded their use. In 1887, Weiblen left Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s and started his own marble and granite company.[5] His first office and show room was located at 233 Baronne Street, a location he expanded by 1893.[6] Weiblen’s big break came in 1891 when his company won the contract to construct the memorial obelisk to New Orleans Superintendent of Police David Hennessy. Hennessy was murdered on October 15, 1890, an event which sparked riots in New Orleans and led to the lynching of eleven Italian-Americans. The contest had been open to many New Orleans monument men, including Charles A. Orleans, the city’s prominent monument builder at the time.[7] The monument was described by national trade periodical Stone magazine as “one of the handsomest monuments in New Orleans”:

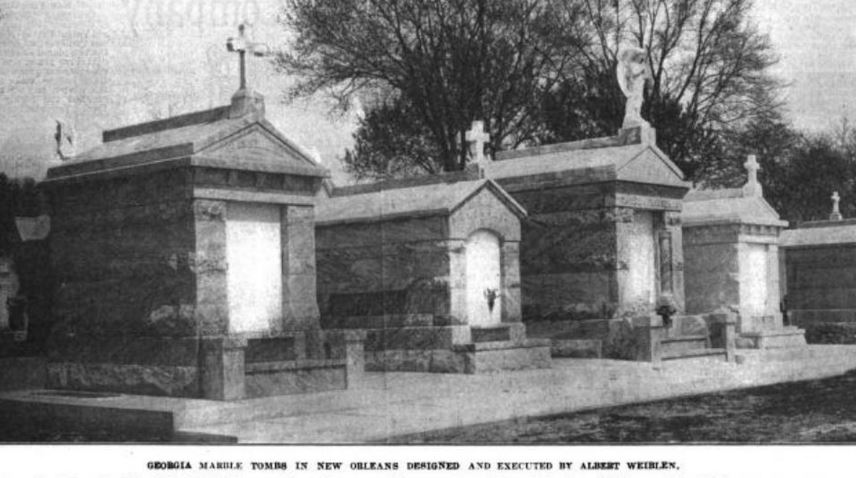

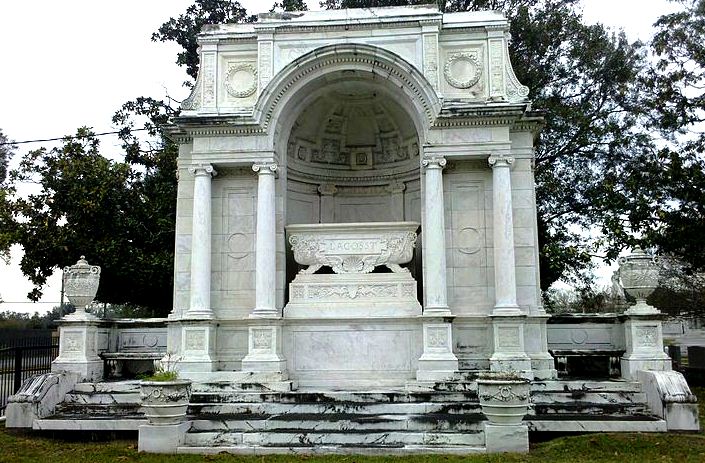

From this location, Weiblen had a workshop complete with powerful equipment to cut, shape, polish, and engrave marble and granite slabs. At the turn of the century, Weiblen’s equipment was not only state of the art (the largest in the South), but was also one-of-a-kind in New Orleans, where technologies were relatively slow to catch on.[10] A skilled marketer and self-advertiser, Weiblen described this equipment in detail in his advertisements, spending nearly half of one circa 1900 advertising booklet explaining its advantages over “the old-time and very laborious manner of cutting by hand.”[11] That Weiblen frequently looked outside of New Orleans for materials and technologies made him, in general, a man of his time. By 1900, the monument industry in the United States was galvanizing as a national trade. Periodicals and trade magazines illustrating the newest and best quarries, saws, cutting methods, and others flourished. Even in New Orleans, Charles Orleans and others had begun to reach outward to peers in the east, newly accessible by infrastructure. Yet Weiblen certainly had a flare for this type of resourcefulness. In 1905, he recruited stonecutters directly from Barre, Vermont, for his shop in New Orleans.[12] The stonecutting shop on City Park Avenue holds in itself a history as visible as any of Weiblen’s tombs. Expanded into the company’s primary sales office in 1907, by the 1920s Weiblen came into possession of five marble sculptures that were once part of the old New Orleans Cotton Exchange. Two of these sculptures, caryatids from the Exchange entranceway, were incorporated into the showroom entrance. The other three, representing Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture, were scrapped for their marble, fell victim to vandalism, or were used as road fill, respectively. The caryatids, however, remain in the Weiblen building, which now houses the Orleans Parish Communication District.[13] The Quarry Man In 1911, Albert Weiblen and his son George leased an interest in a quarry at Stone Mountain, Georgia, from the Venable Brothers company. This was one of a number of savvy moves by the elder Weiblen that helped him cut down his supply chain. By the 1930s, Weiblen would lease another quarry in Elberton, Georgia. His sons, George, Frederick, and John, would all live at the Georgia quarries.[14] In the 1920s, the Weiblens – specifically George and Frederick (who died in 1927) – would begin a long journey of involvement in the carving of the Confederate monument at Stone Mountain, which would not be completed until 1970, the year of George’s death. At these quarries, Weiblen further expanded his infrastructural advantage. By 1936, Weiblen had constructed a full-service carving shop on-site at his Elberton quarry – complete with one of the largest air compressors in the country.[15] Paired with the rail spur he had also built, this permitted Weiblen Marble and Granite to streamline its orders directly from the source. In 1940, Weiblen moved all of his manufacturing operations to Elberton. From this point on, tombs, monuments, and other orders would be ordered from catalogs by customers in New Orleans, manufactured in Elberton, and sent direct by rail to Louisiana, ready for assembly.[16] This advantage also allowed Weiblen to flood the New Orleans market with the products of his quarries, directly transported by rail from their source. Between 1900 and 1940, Weiblen's activities bolstered a stylistic and material shift in New Orleans cemetery architecture. Granite was much more accessible than in the past, and led to new uses as facing and coping material. Georgia marble overtook other sources for new closure tablets, copings, tomb claddings, and other elements. Ever on the marketing edge, Weiblen Marble and Granite even coined a new name for a specific type of Georgia marble, distinguished by sweeping gray and white color patterns: Georgia “Creole” marble (now called “solar gray”). Other burgeoning New Orleans suppliers took up the source, leading Creole marble to be found in large sections of cemeteries like Greenwood, Masonic, and Metairie. Weiblen also attached his name to the granite his company supplied, which is known even today in some circles as “Weiblen gray.” A Cemetery Family Weiblen’s success was passed on to his surviving sons, George and John. George Weiblen operated the Stone Mountain and Elberton interests until his death in 1970. John Weiblen, alternately, assumed his father’s mantle as president of Weiblen Marble and Granite, after Albert Weiblen’s retirement. It was at this time, between 1948 and 1951, that the family company assumed controlling interest in Metairie Cemetery Association. While the purchase of arguably the most prestigious cemetery in New Orleans would have been a grand accomplishment, it also coincided with a larger trend among New Orleans stonecutters in the 1940s.[17] With the monument industry widening to a national scale, and paired with other factors surrounding cemetery management and use, the traditional model of the New Orleans stonecutter that once suited in the nineteenth century was no longer adequate after World War II. This trend was present across all New Orleans cemeteries. In Protestant Girod Street Cemetery, the position of sexton (caretaker), historically held by a stonecutter, was eliminated. This was true also of City-owned cemeteries like Lafayette, Carrollton, Holt, and Valence, in which the position of sexton was eliminated and the management of cemeteries delegated to the City Department of Property Management. The role of the stonecutter, then, was no longer supported by specific cemeteries.[18] Across New Orleans, it became more economically feasible for stonecutters and monument men to shift paradigms from being caretakers of cemeteries to owning the cemeteries outright. Sextons of the Lafayette Cemeteries for three generations, the Alfortish family moved to Gretna and opened Westlawn Cemetery. Victor Huber, monument dealer and caretaker of St. John Cemetery, assumed controlling interest of that burial ground and opened Hope Mausoleum. In 1951, the Stewart family purchased property adjoining Metairie Cemetery and opened Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum.[19] In this sense, Weiblen’s shift from producer of Metairie’s monuments to owner of Metairie’s business was a natural one. John Weiblen preceded his father in death in 1956, leaving his widow, Norma Merritt Weiblen, to manage Metairie Cemetery, which she did so until the property was purchased by Stewart Enterprises, Inc., in 1968.[20] Passing the Torch According to son George, on the morning of May 1, 1957, Albert Weiblen “said he wanted to lie down before breakfast… took one deep breath and he was gone.” At the age of 99 years, Albert Weiblen died, leaving a legacy of innumerable monuments, buildings, statutes, and sculptures behind him. Still working on the Stone Mountain sculpture in the 1960s, George Weiblen noted that he wanted to find a way to carve his father’s name into the stone, “I don’t know how I will work his name in, but there is a way.” Long after Weiblen’s death, the cemeteries of New Orleans bear the mark of his work at nearly every turn. One estimate suggests that nearly half the tombs and monuments in Metairie Cemetery were constructed by Weiblen’s company.[21] In fact, a street off of Canal Boulevard near Greenwood Cemetery is even named after the great monument man. Albert Weiblen was buried in Metairie Cemetery, under a red granite monument. Weiblen's monuments, tombs, buildings, and other projects are innumerable. Weiblen even designed and built the Cuban capitol at Havana. The collection of images below is only a small example of the work of his lifetime.

[1] Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, and Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 55, 62; “Time Marches On, but Weiblen Memorials Remain to Remind,” Times-Picayune, January 25, 1937, 170.

[2] Emily Ford, The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana (MS Thesis, Clemson University, 2013), http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1613/, 96. [3] Ibid. 121-132. [4] Ibid. 164-181. [5] “Time Marches On, but Weiblen Memorials Remain to Remind,” Times-Picayune, January 25, 1937, 170; Soards’ New Orleans Directories, 1885-1910, these directories discourage the notion that Weiblen actually purchased Kursheedt & Bienvenu, which continued until 1901. [6] “Albert Weiblen Marble and Granite Co., Inc.” Times-Picayune, January 25, 1937, 170. [7] Huber et. al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 61-62. [8] “The Hennessy Monument,” Stone – An Illustrated Magazine, Vol. V (June-November 1892), 142. [9] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8; “A Big New Orleans Plant,” Rock Products, Vol. VII, No. 7 (January 1908), 23. [10] “A Prominent Southern Establishment,” The Reporter, Vol. 32 (August 1899), 7. [11] c. 1900 advertising pamphlet, Weiblen Marble and Granite Company, from Tulane University Southeastern Architectural Archive, Collection 39. [12] “Wanted,” Barre Daily Times, July 26-30, 1905, 7. [13] “More about the caryatids,” Times-Picayune, November 17, 1987, 12. [14] “Fred. E. Weiblen Succumbs Here: Was Executor of Granite Work on Confederate Monument,” Times-Picayune, April 12, 1927, 3. [15] 1936 advertising brochure, Tulane University Southeastern Architectural Archive, Collection 36. [16] 1946 advertising brochure, Tulane University Southeastern Architectural Archive, Collection 36; “Marble Works as New Policy,” Times-Picayune, October 2, 1940, 11. [17] “Stone Company Executive Dies,” Times-Picayune, March 23, 1956, 5; Huber, et. al., 59. [18] “Girod Cemetery Vandals Hunted,” Times-Picayune, June 7, 1952, 3; “A Strong Fund,” Times-Picayune, August 23, 1942, 10; Ford, 116. [19] “Lake Lawn Park Plans Revealed: One of Largest Mausoleums in US Promised,” Times-Picatune, March 8, 1950, 42. [20] “He brings city of dead to life,” Times-Picayune, April 14, 1985, B-8. [21] Huber, et. al., 55. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly