|

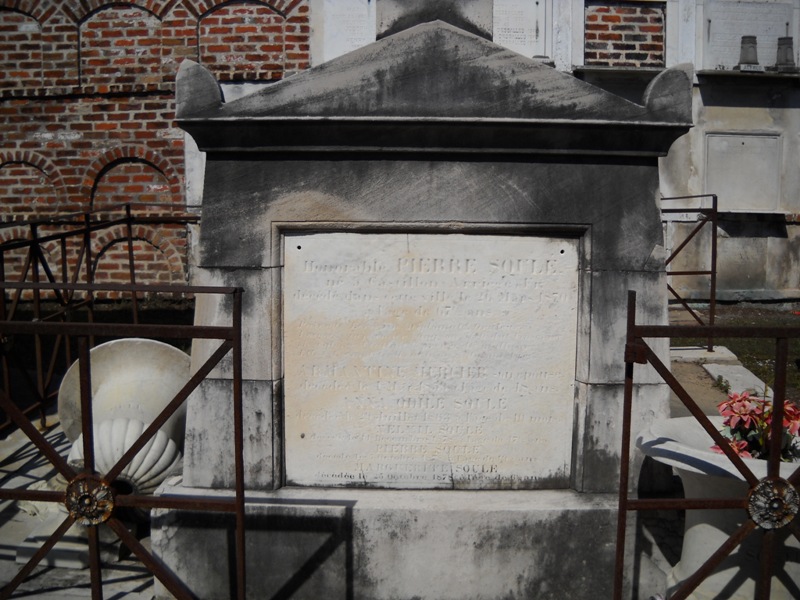

Recently, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC transcribed the burial records of the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, thanks in part to a grant from genealogist Megan Smolenyak. The Society was absorbed by the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans in 1900. Through this research and through extended investigation into the history of the society, its members, predecessors, and descendants, a rich portrait of the life of French-speakers in nineteenth- and twentieth-century New Orleans emerged. Today, we share the history of that society and its many milestones, members, and tombs. ARTICLE I: The association aims to improve physical, moral, and political fitness of its members; to lend each other assistance and relief in misery; to promote each other’s wellbeing, by council and by example; to collectively inspire the rights and freedoms of the home in all countries, and the practice of the duties, which alone can make them worthy; these are the primary obligations as members define them. – from the original constitution of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans, 1843 (translated from French).[1] The First French Benevolent Society in New Orleans On March 14, 1843, after four years of preliminary incorporation, the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (French Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society of New Orleans) was formally established with twenty-seven members. In its own words, the society formed as a result of increasing Americanization of the French colonial city after the Louisiana Purchase and into the Antebellum Era. The Sociètè Française was the first of many organizations in New Orleans with the aim of preserving French language and identity among its members. The Sociètè in New Orleans crafted their organization in the image of fraternal and masonic organizations in France, exemplified by the Grand Orient de France.[2] Similar values were emphasized: brotherhood, charity, social solidarity, and citizenship. The French model of freemasonry also emphasized laicity, or secularism. Among the founding members of the Sociètè in 1843 was a man who himself embodied the political nature of French freemasonry. Pierre Soulé (1801 – 1870) a French native and revolutionary who settled in New Orleans in the 1830s, shaped the early goals and tone of the Sociètè. However, he was elected to the United States Senate in 1847 and thus truncated his involvement. In this year, the Sociètè merged with the French Consulate. Minute books and histories of the Sociètè suggest that after Soulé’s departure, the political aims of the organization were abbreviated in favor of a charitable and social mission.[3] The Sociètè would come to be known for many things – its Bastille Day celebrations, its protection of the French language, its role as the French consulate for some time – but it was likely best known for its Hospital, which was an institution for over a century. French Hospital In the same year as the Sociètè’s founding, a French visitor to New Orleans donated thirty thousand bricks for the construction of a place in which the members could gather. The material was used to build the first French Hospital on Bayou Road near North Robertson Street, described by historians as “a center-hall, gable-sided, double galleried residence.[4]” The hospital, or Asile de la Société Française, cared for Sociètè members and their families. From 1847 to the early 1860s, the organization weathered multiple yellow fever epidemics in which as much as half of the membership was hospitalized.[5] In the early 1860s, the Hospital moved to St. Ann Street, a property donated by then-President Olivier Blineau. Blineau died shortly thereafter and was given the posthumous title of “Father of the French Society.” Originally meant only for society members, French Hospital was opened to all sailors of the French fleet in November 1862, in the event that an illness may require a stay on land.[6] With few exceptions, the Hospital was expressly for the use of members, their families, and those sponsored by members until 1913. In 1913, French Hospital expanded under the decision that “it was finally decided to build a clinic to treat strangers.[7]” Over the next thirty years, the Hospital would include a maternity ward, modern X-ray machines, and operation rooms. The original 1913 building became a well-known edifice on Orleans Street near Claiborne Avenue.[8] Tombs and Burial Benefits Throughout New Orleans history, it was common for societies to form around commonalities of nationality, profession, or background. Most societies would provide benefits similar to those provided by fraternal orders or by modern-day insurance companies. Among these benefits was frequently the option of burial in a society tomb, as well as funereal benefits for survivors. The Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans spared little time in establishing a society tomb for itself. On March 14, 1850, the Sociètè acquired a large lot in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 on Basin Street with the financial aid of the French Consul, M’r Roger. By August of the next year, the first stone of the tomb was laid at a formal ceremony. Beneath this stone, Sociètè officers laid a lead box, in which a copy of the organization’s Constitution, and parchment containing “the names of the President, members of the Consulate, and all members of the society” were placed.[9] The Classically-inspired tomb with an intricate sarcophagus at its apex was completed in the following years. In the early 1850s, the size of the tomb would have overwhelmed the landscape of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. The similarly-imposing Italian Benevolent Society tomb would not be built until 1857. The cross-gable roof of the tomb supported four cast-iron lamps (now missing), in addition to its large sarcophagus, giving it the appearance of a temple. Each corner of the tomb featured an upright torch fashioned of cast plaster. In historic photographs of the tomb, these torches were painted black.[10] In 1853 and 1856, President Blineau donated two additional lots in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 to the Sociètè. Either one of these donations may have been for the purpose of building an addition to the tomb. As is visible in the 1895 Library of Congress photograph, a smaller structure was built to adjoin the original tomb, comprised of fifteen vaults. This expanded the Sociètè’s burial capacity to seventy vaults, all of which could be reused over time.[11] Possibly as a result of a yellow fever epidemic in that year, rumors flew in 1867 that St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 would be permanently closed. In response, the directors of the Sociètè organized a picnic fundraiser to construct a new tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. The nearly $1,000 raised was utilized for the purchase of a lot, which was donated to the Sociètè. Mentions in Sociètè records as well as newspaper resources suggest that a society tomb was in fact built in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 for the use of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans. However, no tomb today bears the society name. The Sociètè maintained and repaired their tombs regularly, as was (and is) necessary with New Orleans tomb structures. In 1897 alone, the organization set aside nearly $500 por le fonds du Tombeau.[12] Regular limewashing, painting of plaster elements, cleaning of lamps and urns, and filling inscriptions with copper-based paint were annual expenses that contributed to the well-kept, beautiful structure seen in the 1895 Library of Congress photograph above. Funeral expenses were also part of member benefits. In an 1897 annual report, the Sociètè outlined these benefits specifically, including:

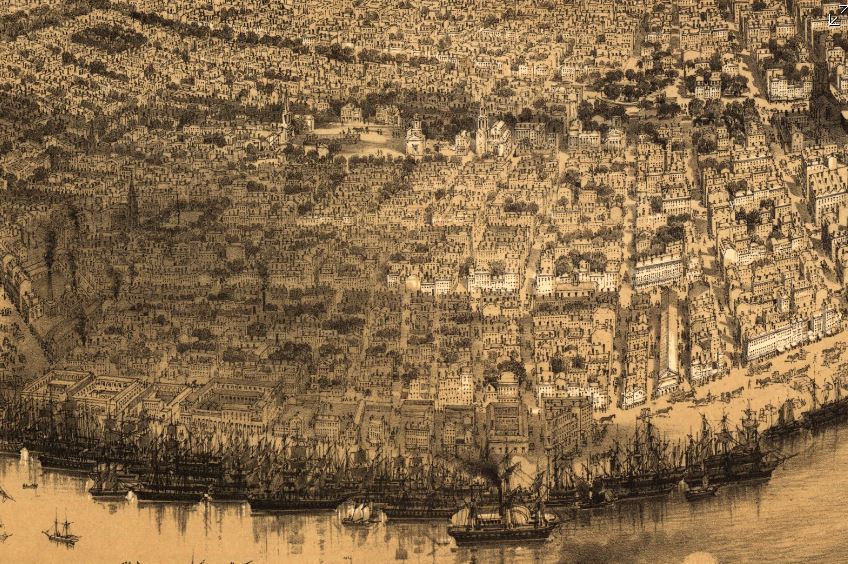

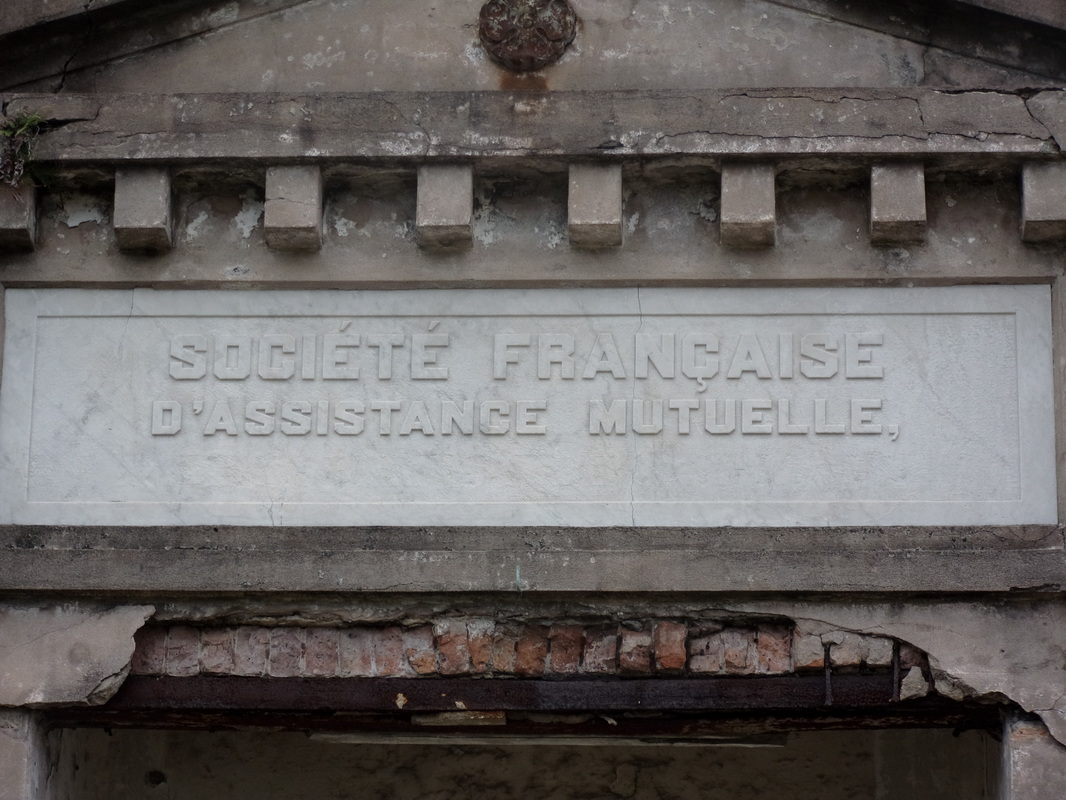

A Sister Society in Jefferson As the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans flourished through the 1850s and 1860s, an additional population of French-speaking people in what was then the City of Jefferson organized their own benevolent society. In the 1850s, the City of New Orleans was much smaller, and bounded on its upriver side by the Faubourg St. Mary and, farther upriver, the City of Lafayette. Over the course of the nineteenth century, New Orleans successively incorporated these municipalities into itself, creating the modern landscape of the city. Between modern-day Toledano and Joseph Streets, and bounded on the downriver side by the former City of Lafayette, the City of Jefferson was incorporated in 1850. Comprised of the Faubourgs Plaisance, Delassize, Bouligny, and others, the city would only remain independent for twenty years before being incorporated into the larger City of New Orleans.[13] It was here that the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson formed in 1868. The French speakers who lived Jefferson Parish and formed the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson were in many ways similar to their counterparts in New Orleans proper. In fact, in many cases they were related. Members of the Tujague and Carerre families joined and served as officers in both societies. Members of each group were often natives of the same departments in France, primarily the Pyrenees and Gers. Many had family in St. Bernard Parish as well as Orleans and Jefferson.[14] The Jefferson Sociètè was comprised of men who lived with their families “near the slaughterhouses,” or who lived on Tchoupitoulas, or near the St. Mary’s Market. They collaborated with and shared members with the Sociètè de Bienfaisance des Bouchers (the Butcher’s Society) who in 1873 brought the famous Slaughterhouse Case to the Supreme Court. A number of Jefferson Sociètè members were buried in the Butcher’s tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. The Jefferson Sociètè built its large, Classically-inspired, forty-vault tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 around 1872. The tomb is of extraordinary height, particularly in the landscape of this cemetery. Its primary gable pediment was carved with the name of the society, which once read “Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Ville de Jefferson,” although the “de la Ville de Jefferson” portion of the inscription appears to have been chiseled away after 1900. Below the pediment are stucco dentils, and on each side are cast-iron florets which likely cover structural tie-rods. The tomb has a number of unique additional features. On each side of its primary façade are niches which were once painted a brilliant Prussian blue, a historic pigment made with iron oxide. In each of these niches were marble statues of kneeling women, one of which had her hands raised in prayer, the other’s hands were crossed on her chest. Both of these statues were stolen between the 1950s and 1980s. The tombs gable-roof side projections hold most of its burial vaults, each enclosed in marble tablets and divided by slate slabs. All tablets of this tomb are uninscribed, leaving the names of those buried within to mystery until the recent transcription of burial books – which revealed the names of at least 150 people buried in this tomb between 1872 and 1900. The Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson participated in the celebrations of a number of French societies in the city. In addition to the New Orleans Sociètè, the Jefferson Sociètè was frequently documented in relationship with the Fourteenth of July Society and the Children of France. 1900: Merging of the Societies By 1896, at its twenty-seventh anniversary, the Jefferson Sociètè had “fifty or sixty” members – a roster that the Daily Picayune regarded as “not quite so large a membership now as at other times in its history.”[15] Officers from the Butcher’s Society and the New Orleans Sociètè, the French Orpheon, and the Fourteenth of July Society raised glasses of wine to the Jefferson officers B. Tujague, O.M. Redon, F. Desschautreaux, T. Abadie, and M. Despaux – most of whom would eventually be buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. It was only four years later that the dwindling numbers of the Jefferson Sociètè merged with their older counterparts at the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans. The merger was completed on January 3, 1901, which records report “brought 41 new members to the society. It also brought to the Society a tomb of forty vaults, nearly new, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2.”[16] The New Orleans Sociètè had merged with other organizations before, beginning with the French Consulate in 1847. In 1895, they also absorbed the Philanthropic Culinary Society of New Orleans, who brought with them an additional burial place: a five-vault tomb located in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street.[17] A Centennial Celebration and Gradual Decline While the New Orleans Sociètè had gained the members of its Jefferson counterpart, its own members were dwindling. This was the case for many benevolent societies in New Orleans after the 1930s. As the need for private hospitals waned, so did French Hospital. In the case of other societies who supported other causes such as orphanages or schools, the need for their ministries decreased with the rise of social services. As insurance corporations developed, private societies no longer fulfilled a necessity. For the French society, decreased interest in the French language likely took a toll, as the New Orleans Sociètè operated exclusively in that language. In 1943, the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (and, by merger, de la Ville de Jefferson) celebrated its 100th Anniversary.[18] A celebration was held at the French Hospital at 1821 Orleans Avenue, with a dance to follow at the American Legion. The festivities appeared to hold true to the organization’s civic dedication. French leader Andre Lefargue addressed the crowd with patriotic notions of the French and Americans once again fighting in a war together. Appeals were made to the crowd to donate to the Red Cross for the war effort. Nine French cadets training at the New Orleans Naval Air Station were special guests of honor.[19] Said society president Henry Bernissan at the centennial celebration, “the first 100 years of the society is merely the initial performance. We expect to improve our methods with every passing day.”[20] Yet the Centennial pamphlet published by the society seemed to suggest a different prescience: The current charter does not expire until the year 1972. Therefore, the Society has 29 years to run. It is hoped that the majority of the current members celebrating our centennial will prosper alongside the society until the end of its charter.[21] On October 31, 1949, only six years after its centennial, the closure of French Hospital on Orleans Avenue was announced.[22] The building was sold to the Knights of Peter Claver, an African-American Catholic Society, who utilized the building until the 1970s, when an adjacent structure was built. The French Hospital/Peter Claverie Building was demolished in 1986. The Knights of Peter Claver buiding remains on this site. The exact year in which the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans formally disbanded is unclear. Unlike their various balls, benefits, picnics and celebrations, this milestone in the organization’s history was not published in newspapers. However, it does not appear as if the Sociètè survived to the end of its charter in 1972. In a 1972 newspaper article, a passing reference was made to the Sociètè, “which for many years maintained the old French hospital on Orleans Street. The French Society folded a number of years ago.”[23] A Legacy of Burial Places Physical evidence of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle is scant in the landscape of modern New Orleans – except for in the cemetery. Each day, hundreds of visitors pass the Sociètè Française tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Without its cast-iron lamps and jet-black torches, it fades into the cemetery scene a little more than it once did, but it remains. For the more than 150 people buried in the Sociètè Française de Jefferson tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, that memory is much more tenuous. A number of trees that began growing in the tomb roof in the 1940s were cut down only this year, leaving a structure in significant need of repair. The brilliant colors of the blue tomb niches, the contrast of its white walls against black slate, its green copper drain pipes, have all faded to flat greys and exposed brick. Without names on the tomb tablets, it has been difficult for families to realize their ancestors are buried within. Yet with this project it is our hope that new resources will supply stakeholders with important information with which to regrow a connection to this remarkable structure, which represents more than a century of French fellowship in New Orleans. In our next blog post, we will share the lives of the people buried in this tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. The full burial rolls of interments into this tomb from 1872 to 1900 (up to the society’s merger with Sociètè Française d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans) have been uploaded to FindaGrave, in hopes their descendants may find them. The burial books are also available as an Excel Spreadsheet , MS Access Database, or PDF Document. Click here for burials listed by vault number. [1] Abrege Historique de la Societe Francaise d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, c. 1903, Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection. This and nearly all documentation of the Jefferson and New Orleans societies are entirely written in French. All translations by Emily Ford, who is by her own admission not fluent in French. Difficult phrases are presented in their original French in [brackets].

[2] Founded in the 18th Century, the Grand Orient de France permitted female membership by 1773. Documents of the Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans and of Jefferson suggest that neither society permitted female membership at any time. [3] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, published 1943 by the Sociètè, 9. Louisiana State University Special Collections, MSS 318, 1012. [4] Roulhac Toledano, Mary Louise Christovich, and Robin Derbes, New Orleans Architecture: Faubourg Tremé and the Bayou Road (Gretna: Friends of the Cabildo, 2003), 82. [5] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 19-21. [6] Ibid., 21. [7] Ibid., 39. [8] “New French Hospital Dedicated Yesterday,” Times-Picayune, February 24, 1913, 13. [9] Ibid., 15. [10] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 9. [11] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 19. [12] “Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, Rapport annuel, 1897,” Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection. [13] Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2008), 290. [14] From the records of Sociètè Française de Beinfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson burial books, Louisiana State University Special Collections. [15] “The Old Jefferson Society Celebrates its 27th Birthday,” Daily Picayune, November 16, 1896, 10. [16] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 37. [17] Ibid., 35. [18] “French Unit Will Fete Centennial,” Times-Picayune, March 14, 1943, 11. [19] “Society Marks Centennial Day,” Times Picayune, March 15, 1943, 25. [20] Ibid. [21] Centenaire: Societe Francaise de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de la Nouvelle-Orleans, 1843-1943, 51. [22] “25 years ago,” Times-Picayune, October 17, 1974, 19. [23] Times Picayune, September 24, 1972, 6.

10 Comments

Above: Ceramic portrait and brass cover, Hook and Ladder Cemetery, Gretna, Louisiana. The art of the photograph transferred to ceramic belies a hidden history in New Orleans cemeteries. In more typical (belowground) cemeteries throughout the United States, photo ceramic portraits are often the most remarkable feature of the landscape. Here in the Crescent City, they are fewer in number and often outshined by monumental architecture. Yet in the midst of curious tombs, grand Continental designs, and stories of intrigue, they remain: Small, uniformly-sized, concave ceramic disks onto which timeless photographs of the deceased have been fired. Happy couples, glamorous ladies, innocent children, all immortalized on their tablets and headstones. Perhaps even more so than memorial sculpture, porcelain photographs connect the cemetery visitor with the cemetery resident, gazing out from the realm of years passed.

Bulot and Cattin’s process was only the first iteration of a “transferotype” or transferal processes of original images to hard surfaces. Most involved the same basic method in which the original image was duplicated via the collodion process, the collodion layer was then soaked until it separated from its glass plate, and slipped over the ceramic disk. After this preparation, the ceramic was fired in a kiln until it was fixed. After firing, the final product was often brushed with enamel. Myriad modes of image transferal were patented and modified by various nineteenth century inventors, including Alphonse Louis Poitevin, Mathieu Deroche, and Lafond de Camarsac (who won a gold medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition for his process). The intricacies of each process are not necessary for this story, but are exquisitely explained by the Dutch Enamelists Society (Vereniging van Nederlandse Emailleurs) here: History of Enamel Photography Photo Porcelain in the United States In both the United States and in Continental Europe, the use of photo porcelain on memorials and monuments became popular among Southern and Eastern Europeans. In Italy in particular, it is said to have become widespread. Evidence or literature to support why photo porcelain was more desirable among these communities is scant. In the United States, most sources suggest that photo porcelain was a way for immigrants to maintain connections to family and culture in a strange land.[3] Prior to the 1890s, portraits were obtained by families through retailers (often photographers) who ordered their wares from specialists in Europe. This changed in 1893 when Joseph Albert Dedouch established his own patents and company in Chicago, Illinois. Dedouch’s company produced a vast number of porcelain photographs. Dedouch was so successful that his products were given a new name – “Dedos.” Over time, the finer aspects of the art developed – the addition of chromatic tints to color the photograph, and manual editing of images to improve overall appearance.

Ceramic portraits in Savannah Cemeteries like Laurel Grove and Bonaventure display many of the same issues these artifacts face throughout the country. Chips, impact marks, and theft are common. Ceramic Portraits in New Orleans The tradition of ceramic portraits in New Orleans, however, appears to have caught on much later. From 1910 to 1930, other trends such as Georgia marble, tree-trunk monuments, and advances in stonecutting technology appear contemporary with the rest of the country. Conversely, nearly all photo porcelain dates from the 1950s onward. Even from this period to the present, ceramic portraits are rare. There are a number of reasons why this may have been the case. Photographers and monument companies, who would have typically brokered the sale of ceramic portraits, may have simply chosen not to tap into this market until much later. It is possible, as well, that the process of constructing, purchasing, and maintaining above-ground tombs seemed incongruous with the installation of these artifacts. What is evident from the presence and location of these portrait is that, like the rest of the country, they remained popular among Italian immigrants and Americans of Italian descent. Perhaps the only cemetery in which ceramic portraits are commonly visible is St. Roch Cemetery No. 2, in which the New Orleans Italian community has a distinct presence. Above: Photo porcelain portraits from St. Roch Cemetery No. 2, dating from the 1950s through the 1980s. (Photographs by Emily Ford)

As for the famous “Dedos,” the Dedouch company survived the twentieth century intact and was sold in 2004 to Canadian company PSM. The Canadian company still sells the “Dedo Classic,” although these portraits are pigmented by precision machinery, whereas the original Dedouch portraits were hand-painted for more than a century. Preserving photo-ceramic portraits is a multi-faceted and nuanced task. It must require aspects of documentation, materials conservation, and skilled artisanship. For by preserving the antique processes by which these portraits were made, their cultural heritage as a whole is safeguarded for future generations. Of course, it is impossible to protect resources that have never been defined. In New Orleans, no comprehensive attempt has ever been made to catalog instances of photo porcelain in cemeteries. If they are to be preserved for the future, and protected from vandalism or theft, documentation is essential. In a world in which images have become ubiquitous yet ephemeral, photo-ceramic memorial portraits offer a connection to the most deeply personal and sentimental aspects of memorial art. The opposite of ephemeral, their tangibility and endurance create in our cemetery landscapes a memory almost even more real than the people they memorialize. [1] Johann Willsberger, The History of Photography: Cameras, Pictures, Photographers (Doubleday: 1977), 145; “Photographic Correspondence,” from Notes and Queries: Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc. Vol 12, July-Dec, 1855, 212.

[2] Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, Volume 2 (London: George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1869), 66. [3] Ronald William Horne, Forgotten Faces: A Window into Our Immigrant Past (San Francisco: Personal Genesis Publishing, 2004). This publication may be the only book specifically dedicated to photo porcelain, although it focuses almost entirely on the cemeteries of Colma, California. Marilyn Yalom, The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 20-21. [4] Maison Blanche advertisement, Times-Picayune, March 30, 1932, 26; Sears Roebuck prices from The American Resting Place, 20. At the end of the main aisle in Square 1 of St. Louis No. 2 is a simple tomb with a low-pitched gable roof. Coated in modern cement and latex paint, it is difficult to determine much about its original appearance. Perhaps it was once coated in brightly-colored stucco, or its roof tiled in slate or terra cotta. Ironwork may once have enclosed its simple design. Without the fortunate discovery of an historic photograph, which is extremely rare, the elegant past of this tomb may never be known. But the de Armas tomb offers a hint to the scrutinizing eye. Its marble closure tablet is embellished with an ornate relief carving depicting a winged hourglass encircled with a floral wreath. The hourglass is surrounded by a snake eating its tail – the ouroboros – a symbol of immortality. Among the few depictions of the winged hourglass in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, this carving is by far the most detailed. Such a carving is indicative of a level of style and craftsmanship long faded from New Orleans cemeteries. At one time it was not alone in its ornamental beauty, but instead belonged to a rich landscape of beaded wreaths, draped urns, and weeping angels. Even today, the de Armas tomb is not alone in one regard. Nearly three miles away, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2’s younger sister, St. Louis No. 3, stretches along the edge of Bayou St. John in long aisles. Amidst its large lots and photogenic tombs is the tomb of the Depaquier family. Uncompromised by modern repairs, the faded stucco walls bely that the tomb was once limewashed a dark rose color. The pitch of its roof is reminiscent of the de Armas tomb. The closure tablet of Dupaquier tomb is bordered with a carved braided rope. Atop its simply-lettered epitaph is a winged hourglass nearly identical to that found on the de Armas tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Studies of cemetery craftsmanship in New Orleans have shown that few motifs, materials, or methods in cemetery stonecarving are the result of happenstance. Who carved these tablets? What do they symbolize? And why did the Dupaquier and de Armas families end up owning identical tablets? The de Armas and Dupaquier Families The two tombs are the burial places of the patriarchs of their respective families. In St. Louis No. 2, Michel Theodore de Armas (sometimes listed in documents as Michael or Miguel), was a notary and lawyer who was born in New Orleans in 1783 and died in 1823.[1] In St. Louis No. 3, Claude Dupaquier was born in France in 1806, arrived in New Orleans in the 1840s, and died in 1856.[2] Between 1823 and 1856, life expectancy was around 37 years, so that these men died at age 40 and 50 (respectively) is unremarkable. Both de Armas and Dupaquier had children that became important members of New Orleans’ business and social circles after the Civil War. Dr. Auguste Dupaquier, who is buried with his parents, was described as having a “gentle, loving, and kindly temperament, mixed with firmness and rare energy, and he secured the affections of all whom he approached.[3]” Dr. Dupaquier had no discernable interaction with the children of de Armas, and it is unlikely that the families had enough relation to construct matching tombs knowingly. One significant similarity between the Michel de Armas and Claude Dupaqueir was their preference for the French language. Both tablets are carved in French.

In nineteenth century New Orleans, a person’s linguistic and cultural identity often determined who they chose to carve their final epitaph or build their eternal resting place. For de Armas, or his widow, Gertrude St. Cyr Debreuil, it would have been a given that they chose Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux. New Orleans cemeteries are populated with the small, often overlooked signatures of local stonecutters. Often these signatures wear away, and craftsmen often neglected to sign their work at all. Many stonecutters began their careers working for other more established cutters, signing the name of their master instead of that of the apprentice. These realities complicate the study of cemetery craftwork. In the case of the de Armas closure tablet, a small, clean-lettered signature is present at its bottom right-hand corner – MONSSEAUX. The Depaquier tomb retains no signature at all. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux Like Claude Depaquier, Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux (1809-1874) was a French native who arrived in New Orleans as an adult.[4] Present in New Orleans by 1842, Monsseaux is best known as the stonecutter who built many tombs designed by architect J.N.B. De Pouilly. These included many famous tombs in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Monsseaux often worked with other stonecutters in either a master/apprentice role or as business partners. In addition to his work for J.N.B. de Pouilly, his signature is often found beside other cutters like Tronchard and Kursheedt & Bienvenu. Through his entire career, Monsseaux held the same marble yard on St. Louis Street at the corner of Robertson Street – directly beside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 and New Basin Canal. Through his career, Monsseaux also sold marble to fellow stonecutters; he partnered with others to secure equipment and technology that advanced the trade. Most notably, he owned a steam marble works for some time in the 1870s, the rights to which he lent to other cutters Stroud and Richards.[5] Monsseaux’s accomplishments were many, but his clientele was rather distinct. Most of Monsseaux’s signed tablets are carved in French. In this manner, Monsseaux is a French counterpart for German-speaking stonecutters of the time who served a distinctly German clientele. There are always exceptions – Monsseaux built the DePouilly-designed Iberian Society tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Yet the majority of his work served French-speaking clients who belonged to the upper echelons of New Orleans society. Stylistic Inspirations and Symbolism French speaking upper-class New Orleaneans in the 1830s were enthralled with the style and beauty of tombs found in Paris’ Pere Lachaise Cemetery at the time, and Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux gladly catered to that demand. Sarcophagus-style tombs with corner acroteria and inverted torches appeared in St. Louis No. 2 during this time. These tastes adapted through the 1850s and into the first years of St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. Greek Revival temples and Egyptian Revival tombs rose in the squares of the both cemeteries, mimicking the aisles of the great French burial ground. Often, it was Monsseaux who provided his clients with these romantic sepulchers. Pere Lachaise Cemetery is populated with hundreds of winged hourglasses. In fact, the first image to greet the visitor at the cemetery gate is a pair of such hourglasses. This is also the case at Montparnasse Cemetery, also in Paris. The history of the winged hourglass as a funerary symbol appears to split along linguistic and cultural lines in the United States. In the English-speaking Northeast, it is contemporary with the skull-and-crossbones and death’s head, symbolizing the fleetingness of time. In this context, the winged hourglass was contemporary to the 18th century and faded from popularity by the 1830s. French-speaking New Orleans funerary culture developed more closely to that of Paris than its American cousins, however. The winged hourglass is seldom seen in tombs constructed prior to 1820. It does, however, appear to grow in popularity from 1820 through the 1850s, when the de Armas and Dupaquier tombs were constructed. This inspiration was drawn directly from the Parisian cemeteries. And New Orleans was not alone in this inspiration. Not to be outdone as a European city in the New World, Buenos Aires’ Recoleta Cemetery, founded in 1822, hums with the flutter of winged hourglasses. The de Armas and Dupaquier families may never have known each other, but they are together twin scions of a lost cemetery landscape. Opulent with their floral wreaths and outspread wings, their hourglass tablets were likely carved by Monsseaux himself or an apprentice. It is possible, even, that the Dupaquier tablet was a replica of de Armas’, carved by a student still learning his trade. Or, perhaps, both designs were borrowed from a pattern book imported from Paris. In any case, they endure as silent reminders of the importance of each tomb in the larger landscape of our historic cemeteries. [1] Florence M. Jumonville, Ph.D., ‘Formerly the Property of a Lawyer’: Books that Shaped Louisiana Law. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Library Facility Publications, 2009, 7.

[2] Orleans Death Indices 1804-1876. Vol. 17, 312. [3] “Death of Dr. Dupaquier,” New Orleans Daily Democrat, April 8, 1879, p. 8. [4] Charles LeJ. Mackie, “Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux: Marble Dealer,” printed in SOCGram, Fall 1984, 14-16. [5] Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly