|

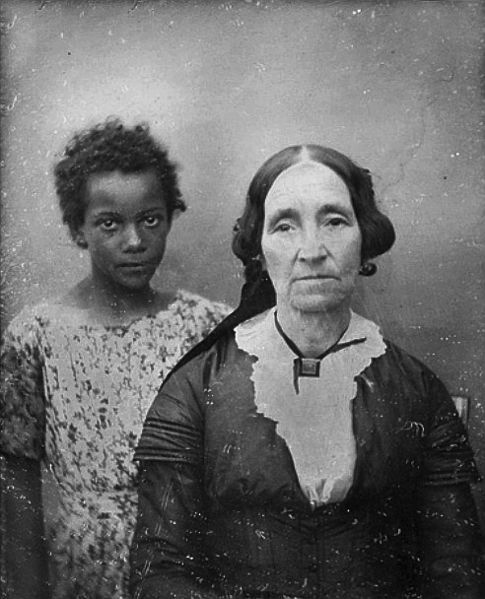

Above: Ceramic portrait and brass cover, Hook and Ladder Cemetery, Gretna, Louisiana. The art of the photograph transferred to ceramic belies a hidden history in New Orleans cemeteries. In more typical (belowground) cemeteries throughout the United States, photo ceramic portraits are often the most remarkable feature of the landscape. Here in the Crescent City, they are fewer in number and often outshined by monumental architecture. Yet in the midst of curious tombs, grand Continental designs, and stories of intrigue, they remain: Small, uniformly-sized, concave ceramic disks onto which timeless photographs of the deceased have been fired. Happy couples, glamorous ladies, innocent children, all immortalized on their tablets and headstones. Perhaps even more so than memorial sculpture, porcelain photographs connect the cemetery visitor with the cemetery resident, gazing out from the realm of years passed.

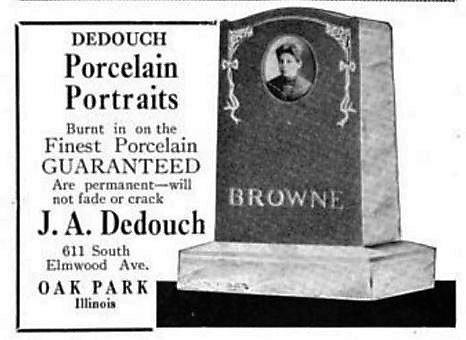

Bulot and Cattin’s process was only the first iteration of a “transferotype” or transferal processes of original images to hard surfaces. Most involved the same basic method in which the original image was duplicated via the collodion process, the collodion layer was then soaked until it separated from its glass plate, and slipped over the ceramic disk. After this preparation, the ceramic was fired in a kiln until it was fixed. After firing, the final product was often brushed with enamel. Myriad modes of image transferal were patented and modified by various nineteenth century inventors, including Alphonse Louis Poitevin, Mathieu Deroche, and Lafond de Camarsac (who won a gold medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition for his process). The intricacies of each process are not necessary for this story, but are exquisitely explained by the Dutch Enamelists Society (Vereniging van Nederlandse Emailleurs) here: History of Enamel Photography Photo Porcelain in the United States In both the United States and in Continental Europe, the use of photo porcelain on memorials and monuments became popular among Southern and Eastern Europeans. In Italy in particular, it is said to have become widespread. Evidence or literature to support why photo porcelain was more desirable among these communities is scant. In the United States, most sources suggest that photo porcelain was a way for immigrants to maintain connections to family and culture in a strange land.[3] Prior to the 1890s, portraits were obtained by families through retailers (often photographers) who ordered their wares from specialists in Europe. This changed in 1893 when Joseph Albert Dedouch established his own patents and company in Chicago, Illinois. Dedouch’s company produced a vast number of porcelain photographs. Dedouch was so successful that his products were given a new name – “Dedos.” Over time, the finer aspects of the art developed – the addition of chromatic tints to color the photograph, and manual editing of images to improve overall appearance.

Ceramic portraits in Savannah Cemeteries like Laurel Grove and Bonaventure display many of the same issues these artifacts face throughout the country. Chips, impact marks, and theft are common. Ceramic Portraits in New Orleans The tradition of ceramic portraits in New Orleans, however, appears to have caught on much later. From 1910 to 1930, other trends such as Georgia marble, tree-trunk monuments, and advances in stonecutting technology appear contemporary with the rest of the country. Conversely, nearly all photo porcelain dates from the 1950s onward. Even from this period to the present, ceramic portraits are rare. There are a number of reasons why this may have been the case. Photographers and monument companies, who would have typically brokered the sale of ceramic portraits, may have simply chosen not to tap into this market until much later. It is possible, as well, that the process of constructing, purchasing, and maintaining above-ground tombs seemed incongruous with the installation of these artifacts. What is evident from the presence and location of these portrait is that, like the rest of the country, they remained popular among Italian immigrants and Americans of Italian descent. Perhaps the only cemetery in which ceramic portraits are commonly visible is St. Roch Cemetery No. 2, in which the New Orleans Italian community has a distinct presence. Above: Photo porcelain portraits from St. Roch Cemetery No. 2, dating from the 1950s through the 1980s. (Photographs by Emily Ford)

As for the famous “Dedos,” the Dedouch company survived the twentieth century intact and was sold in 2004 to Canadian company PSM. The Canadian company still sells the “Dedo Classic,” although these portraits are pigmented by precision machinery, whereas the original Dedouch portraits were hand-painted for more than a century. Preserving photo-ceramic portraits is a multi-faceted and nuanced task. It must require aspects of documentation, materials conservation, and skilled artisanship. For by preserving the antique processes by which these portraits were made, their cultural heritage as a whole is safeguarded for future generations. Of course, it is impossible to protect resources that have never been defined. In New Orleans, no comprehensive attempt has ever been made to catalog instances of photo porcelain in cemeteries. If they are to be preserved for the future, and protected from vandalism or theft, documentation is essential. In a world in which images have become ubiquitous yet ephemeral, photo-ceramic memorial portraits offer a connection to the most deeply personal and sentimental aspects of memorial art. The opposite of ephemeral, their tangibility and endurance create in our cemetery landscapes a memory almost even more real than the people they memorialize. [1] Johann Willsberger, The History of Photography: Cameras, Pictures, Photographers (Doubleday: 1977), 145; “Photographic Correspondence,” from Notes and Queries: Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc. Vol 12, July-Dec, 1855, 212.

[2] Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, Volume 2 (London: George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1869), 66. [3] Ronald William Horne, Forgotten Faces: A Window into Our Immigrant Past (San Francisco: Personal Genesis Publishing, 2004). This publication may be the only book specifically dedicated to photo porcelain, although it focuses almost entirely on the cemeteries of Colma, California. Marilyn Yalom, The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 20-21. [4] Maison Blanche advertisement, Times-Picayune, March 30, 1932, 26; Sears Roebuck prices from The American Resting Place, 20.

2 Comments

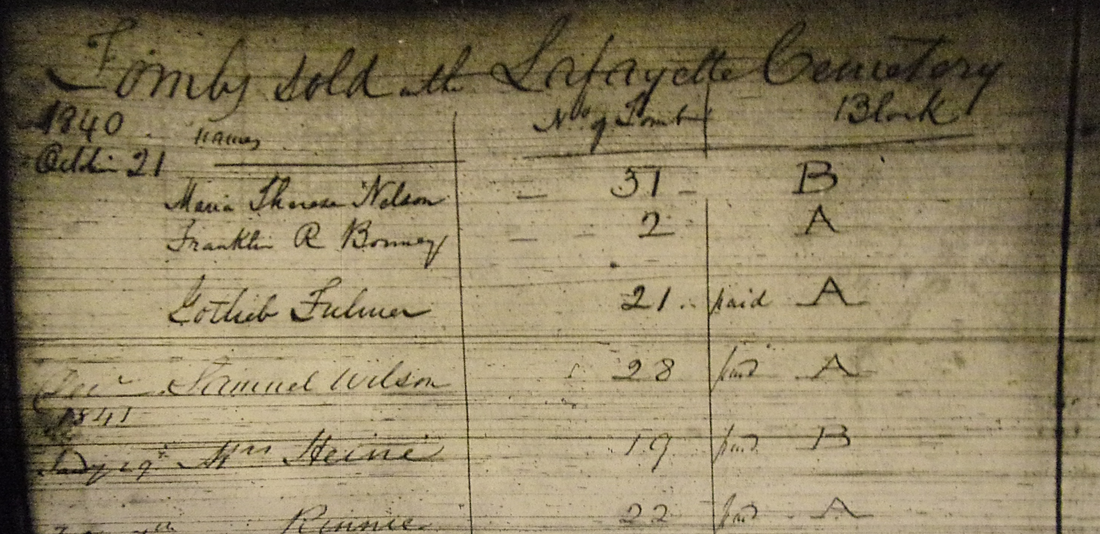

Find your tomb, Research your tomb, Restore your tomb The text below is excerpted from a recent presentation to the 2016 Annual Conference of the Louisiana Historical Association, presented by Emily Ford, MSHP, of Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LL New Orleans cemeteries are so unique that the simple mention of them creates a picture in one’s mind. That picture is likely one of intricate aisles populated by stately, yet crumbling, above-ground tombs; long abandoned, anachronistic cities of the dead which offer up stories through their carved tablets. Traditional histories of New Orleans cemeteries have been static, and ever tied to their place in popular culture. For example, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as part of what is now the Garden District. Over the next century, families built above-ground tombs ranging in style from simple masonry structures to grand Classical revival masterpieces. From this foundation, the interpretation of the cemetery usually branches into famous people buried therein, or a focus on specific architectural gems. These interpretations usually rely on a few primary sources. Some cemetery records, selected newspaper articles, and general contemporary observations of the cemetery as it exists in the moment tend to dominate the narrative. What few critical analyses of cemetery architecture exist tend to be repeated through numerous secondary sources. This tends to amplify their subjects as singularly important. For example, the excellent research of Patricia Brady on the stonecutter Florville Foy published in 1993 has been so revisited that the place of Foy among hundreds of other nineteenth century stonecutters appears paramount, as opposed to part of a larger craft community.[1] Beyond the few comprehensive histories relevant to New Orleans cemeteries lie the bulk of what is currently available – histories that focus on cemetery “residents” (for example, Marie Laveau or Colonel Harry T. Hays), high architecture, or the occult. These histories rely on the basic historiographies previously mentioned and typically add curious second-hand stories or rehashed false reports. For example, the translation of the tablet of André Valsin Labarre in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 has been repeated incorrectly for more than a century, but never once has it been noticed that it is located in the wrong lot.[2] Conversely, more dynamic and critical approaches to writing cemetery history will inevitably stumble upon landscapes which dramatically changed as their stakeholders did. For example, the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was not always one of above-ground tombs. The first stakeholders in this cemetery, predominately German and Irish immigrants, found above-ground burial to be perverse, and instead buried below ground. It was not until the 1850s, when their assimilated children gained control of the family lot, that tombs were constructed to emulate the New Orleans ideal.[3] Facts like this not only present a more accurate history of each cemetery, but also accentuate the changing uses each lot would see over time. Sale of lots, demolition of tombs, changes in materials, adaptive reuse, abandonment, and changes in technology are a constant presence in the history of any New Orleans cemetery. Consideration of these details empowers preservationists, stakeholders, and cemetery authorities to more appropriately care for these resources. By shifting the view of cemeteries from that of static landscapes (“outdoor museums”) to one of functional cultural resources, their history and their preservation are dually served. A critical approach to cemetery history combines a multifaceted catalog of primary resources. Original records vary in their condition and availability. With regard to tomb construction, cultures of craft typically focused on the final product and not on drawings, plans, or specifications. In order to piece together the history of a New Orleans cemetery, some creative and rigorous searching is in order. By pairing what primary resources are available with thorough and educated examination of the landscape itself, it is possible to determine the life story of any city of the dead. Original Cemetery Records There are between 32 and 46 historic cemeteries in New Orleans, depending on the criteria employed. Each one is unique in age, architecture, and culture. They also vary in terms of ownership and, thus, quality and location of records. In general, there are four types of cemetery ownership –

Records of cemetery burials, constructions, demolitions, or demographics were kept by the owning body of each cemetery. Owning bodies vary in their methods of access, preservation, and retention of records. Historic Images What cemetery records cannot contribute to the preservation and documentation of cemeteries is often accessible in a variety of traditional and non-traditional photographic resources. The use of historic photographs in the identification of property and the preservation of individual tombs has not been frequently visited. Furthermore, many photographs which can prove crucial to preservation efforts are difficult to find. When located, however, these photographs can tell the story of an entire cemetery, save a tomb from demolition, or re-unite a family with their property. The photographs of Clarence John Laughlin are an excellent example. Recently digitized by the Historic New Orleans Collection, the photographs date from the 1930s through the 1970s. Laughlin’s prolific hauntings through New Orleans cemeteries prove to be time capsules without compare. Identification of precise location of photographs yields not only histories of specific structures but also entire landscapes. For example, a 1920s postcard showing St. Roch Cemetery and a 1907 photograph of Holt Cemetery show an overwhelming prevalence of wooden markers. Comparison with present-day landscapes indicates enormous changes in the use of cemeteries over time – notably, the industrialization of the monument industry by mid-twentieth century. This shift overwhelmingly transformed cemeteries from highly individualized properties maintained by families to largely mono-stylistic landscapes maintained by cemetery staff – or not maintained at all. As we move into the twenty-first century, the presence of Hollywood in New Orleans cemeteries has created a new type of historiography. Productions like Easy Rider, Love Song for Bobby Long, NCIS, and dozens of others with scenes taking place in New Orleans cemeteries inadvertently document them. Easy Rider is a significant example. Fortunately for historians and preservationists, Peter Fonda’s place in the arms of the statue of “Italia” provides an image taken only years before a heavy-handed “restoration” permanently damaged it. Ephemera and Oral Histories Numerous resources exist beyond photographs and scant cemetery records. These require some amount of supporting evidence, and are best paired with observations of the built environment itself. Some ephemeral records were produced by the purchasers of the tombs themselves. Tomb deeds, once a common part of family papers, are rare, but those that do exist show that many tombs have a chain of title. Such evidence is also present in the notarial archives of tomb builders like Hugh McDonald, Paul Monsseaux, and James Hagan. The full potential of all of these resources is reached when paired with on-site examination of the landscape. This is achieved through painstakingly inspection of tombs for alterations, materials, and inscriptions. Larger-scale data collecting also proves fruitful. For example, while primary resources suggest stonecutter Anthony Barret predominately served a German-speaking market, database compilations of his signed work in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm the breadth of his presence in the German community. These conclusions are additionally supported by oral histories and interviews with the ever-dwindling community of cemetery craftsmen and caretakers, whose potential has rarely been formally tapped. In conclusion, the hidden historical record of New Orleans cemeteries reveals dynamic landscapes that were specific to their community, and constantly shaped by that community. By resurrecting these histories, which highlight stewardship, family involvement, and participation with cemetery authorities, these values can be preserved. Through these means, we can more accurately represent New Orleans heritage and community agency for those who take interest in it and are inheritors of it. Have questions about cemetery interment research or architectural histories of cemetery properties? Contact Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. [1] Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.: Master Marble Cutter and Tomb Builder.” Southern Quarterly 32, no. 2 (Winter 1993): 9-20.

[2] Emily Ford, “André Valsin Labarre: Victime de Son Imprudence,” http://www.oakandlaurel.com/blog/andre-valcin-labarre-victime-de-son-imprudence (January 9, 2016). Based on in situ investigation, Archdiocese records, and 1930s WPA Index (housed at NOPL), this well-known tablet has travelled from Labarre’s actual resting place. [3] “History and Incidents of the Plague in New Orleans,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7 (June-Nov. 1853), 798; Bennet Dowler, Researches upon the necropolis of New Orleans, 22; George Edwin Waring and George Washington Cable, History and Present Condition of New Orleans, Louisiana, and Report on the City of Austin, Texas (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1881), 58; John Frederick Nau, The German People of New Orleans, 1850-1900, 15. Architectural histories within the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm this progression from below-ground burials to above-ground tombs and (eventually) copings. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly