|

This blog post is Part Two of a two-part piece on the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. To learn about the history of this French Society, check out Part One here. Recently, Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC transcribed the burial records of the tomb of the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, thanks in part to a grant from genealogist Megan Smolenyak. The Society was absorbed by the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans in 1900. About the Record Books The records of the Sociètè are housed at LSU Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, in Baton Rouge. (MSS 318, 1012) The burial books appear to have been included with the larger collection of papers from the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans (French Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society of New Orleans) which absorbed its Jefferson City counterpart in 1900. The collection is comprised of two books, dating from the tomb’s construction in 1872 through 1900. While later interments were certainly made in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb, their record appears to have been incorporated into another, as-yet unstudied document. Within these two books are the burial documents for 186 individuals. Among these records, 142 people were buried in the society tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, 32 were provided formal burial aid by the society and were interred in family tombs throughout the city, and 12 were not specified as to burial location.[1] Each burial record documents the date and place of the individual’s birth, date and place of death, as well as cause of death and information regarding membership. These documents shed light on the lives of hundreds of people. They allude to intricate familial and professional relationships, personal tragedies, and public calamities. They offer a window into a rich community, the vestiges of which stand silent in this stately yet neglected tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Today we share the stories of those buried within. The Foreign French: Founding Members and their Origins The Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson was organized in 1868 by native-born French men – eight of whom are buried in the Lafayette No. 2 tomb. Much like the New Orleans French society, these immigrants sought fraternity among their countrymen. Incidentally (or perhaps not so much so), most of these men were born in the same French provinces (départments), and often in the same village. The majority of adults buried in the Sociètè tomb originated from two primary areas in continental France: the department now known as Midi-Pyrenees, including Gers, Haute-Pyrenees, Haute-Garonne, and Bass Pyrenees (now known as Pyrenees-Atlantiques), and the eastern departments of Alsace-Lorraine, specifically Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin, and Moselle. These two areas are nearly as geographically disparate as can be, with the former nestled along the Pyrenees mountains at the Spanish border, and the latter at the Rhine River beside present-day Germany.

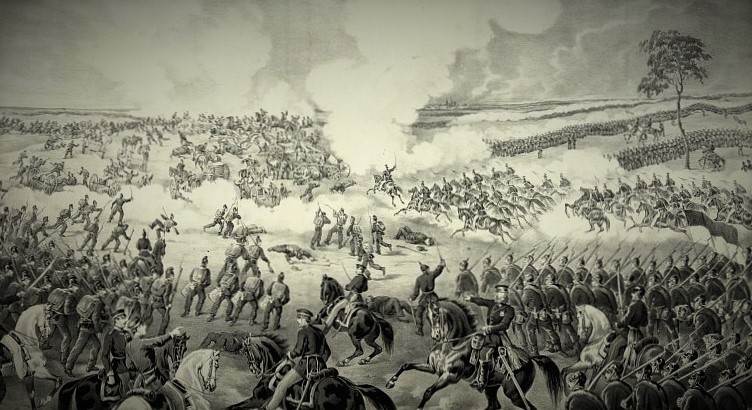

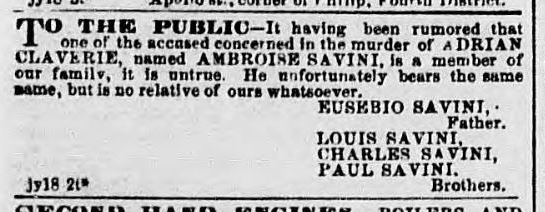

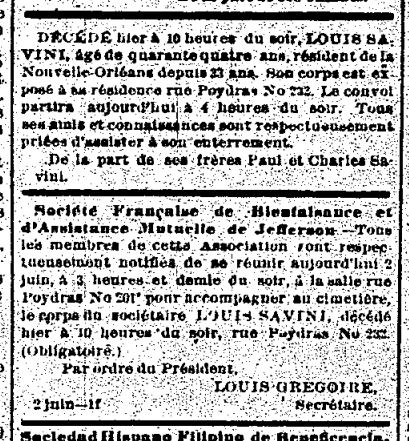

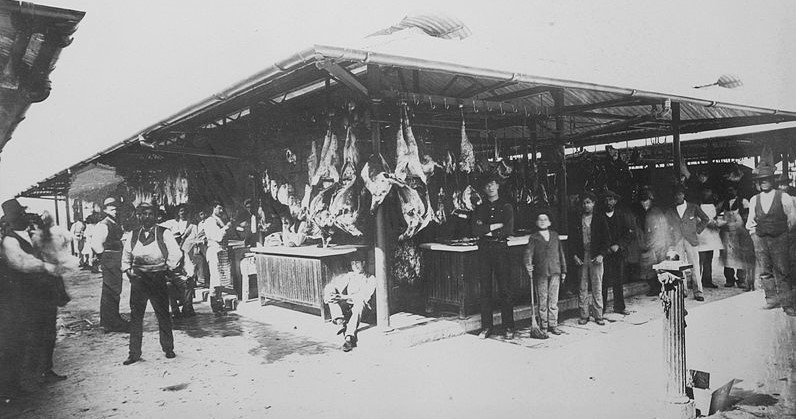

In Alsace-Lorraine, a different climate motivated the eventual members of the Sociètè to emigrate from their homes. The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) forced many Alsatians from their homeland when the controls of the provinces shifted from France to newly-nationalized Germany. For French-speaking Alsatians, both Jewish and gentile, German citizenship was a less than desirable option. New Orleans was an attractive alternative due to its Francophone tradition. Among these Alsatian emigrants were sisters Catherine and Marie Sonntag, both in their early twenties from Altinstadt, Alsace. Nieces of Sociètè member O.M. Redon, they both died of yellow fever within weeks of each other in October 1872. They were buried in vaults 20 and 22 of the Lafayette No. 2 society tomb. While the people buried in this tomb overwhelmingly shared a linguistic and cultural bond, there is no shortage of strangers among the burials in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Although the tomb was built for French society members, those members were not always French. Strangers in a Strange Land: Non-French Buried in the French Tomb A handful of foreign-born non-French people were laid to rest in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. Their stories contribute to the greater narrative of the society which at its heart was thoroughly New Orleanean in its cultural interactions. From Germany, Catherine Deffenback and brothers John and Jacob Schwenck were buried in this tomb at their time of death. The Schwenck brothers owned a saloon together on Magazine Street.[3] Leon Vignes, from Mont-de-Marrast, France, mourned the death of his Irish-born wife, Margaret, in 1884. She is buried in vault 35. Leon died fifteen years later and was buried in vault 38. He was not the only person to join the matrimonial melting pot: The wife of J.M. Gelé was born in England and died in 1872, buried in vault 26. Perhaps the most interesting foreign-born member of the society is not buried in the Lafayette No. 2 tomb but instead only blocks away in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, although no tablet remains to mark his name. Louis Savini was born in 1830 in Mortara, Italy. By the time he was eleven years old, he and his family had taken residence in New Orleans. From the very scant documentation remaining, Savini appears to have led a colorful life. He owned a saloon in what is now the Central Business District on Common Street, near the Mississippi River.[4] For reasons unclear from available records, Savini joined the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson in 1874. Only months after joining the group, however, Savini was struck down by a “cerebral fever,” which could indicate encephalitis, meningitis, or scarlet fever. He died on June 1, 1874 in his home on Poydras Street. The Sociètè not only furnished his burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, but also provided a procession befitting a French society member. Savini was buried in the tomb of his brother, Paul Savini, in Quadrant 2 of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Today, the tomb is in a state of dangerous neglect and has lost the closure tablet bearing Louis Savini’s name. As the Sociètè aged, its members increasingly were New Orleans natives. Over time, both the children of members and other Francophone Louisianans joined, advancing the process of assimilation in a new country. The Family Tomb At least one hundred and forty-two individuals are buried in the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Some were recent immigrants with little or no family left behind. For a striking number of society members, however, the tomb was the final resting place for multiple generations. It has already been noted that Leon and Margaret Vignes rest near each other in this tomb. They are also interred with their son, Joseph, who drowned at the age of 14 in 1891. He is interred in the same vault as his mother. The Fortassin family likely also utilized the society tomb for the interment of multiple generations. In 1870, twenty year-old Gabriel Fortassin, Jr., arrived in New Orleans from Trie, France. His parents joined him as well. In 1882, he married Alexandrine Claverotte.[5] The two would briefly move to San Antonio, Texas before returning to New Orleans. In his lifetime, Gabriel would bury his parents in the society tomb, as well as five of his infant children. When he died in 1927, he was given a French Society burial in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2.[6] One of Gabriel’s adult sons, Baptiste Fortassin was also buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, in 1929. Two years later, Baptiste’s widow Marie Maille joined him. With no Fortassin tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, it is very likely they joined their relatives in this tomb, making it the last resting place of three generations of one family, with at least nine burials.[7] Other families utilized the society tomb similarly. Surnames such as Tujague[8], Abadie, Mouledous[9], Vignes, and Carrare appear multiple times through the burial books, representing multiple generations. These records also show combinations of the above-mentioned names, linked by intermarriage. Eleanor Vignes Tujague and Pauline Mouledous Tujague are both buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 society tomb. Society members formed a strong, interdependent community. They even stood at each other’s deathbeds to witness a last will and testament.[10] Death and burial were only the final threads that tied these French-speaking New Orleaneans together. In life, they lived and worked beside one another. As the French Society of Jefferson, members lived predominately within the boundaries of the former Jefferson suburb (portions of present-day Garden District, Irish Channel, Central City, and Uptown neighborhoods). Burial records note the residences of a multitude of members as near the St. Mary’s Market and along Tchoupitoulas Street. Even more records note residence as simply “aux abbatoirs,” or “near the slaughterhouses.” Which is no surprise: the majorit of members were butchers. A Workingman’s Society The Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson shared members and celebrated social events with the Sociètè de Bienfaisance des Bouchers, or the French Butchers Society. Their enormous, eighty-vault society tomb remains also in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. Members of each society lived near the Mississippi River, where cattle were unloaded at river docks. Until the late 1860s, the City of New Orleans had little regulation regarding the slaughter of livestock. Butchers were free to practice their trade where they pleased, usually near a market where they could sell their wares. This changed with a municipal law that required butchers slaughter livestock exclusively in a city-owned slaughterhouse, the goal of which was to prevent public health hazards.[11] Opposition to this law among butchers of both French societies led to civil unrest and years of legal battles. The case finally reached the Supreme Court in a landmark ruling known as the Slaughterhouse Case. Among the French and Butchers societies, the butcher’s trade was passed through generations and within a tight-knit community. Members lived in close proximity to each other, with addresses at Louisiana, Camp, Chippewa, Annunciation, Constance, Josephine, St. Mary, Tchoupitoulas, St. Andrew, Washington, Magazine, and Rousseau Streets. The propensity to take on the butcher’s trade among these society members is truly overwhelming. One casual cross reference of members’ names with an 1878 directory revealed nine butcher/members alive and working at the time: Gabriel Fortassin, Jr., Jean Abadie, Joseph Barrere, Pierre Lacaze, Bernard Lacoste, John William Lannes (Lannis), Pierre Sabatte, and Leon Vignes. The other three members searched, Victor Brisbois, Ulysses Mailhes, and Jacob Schwenck, were all listed as saloon owners or bartenders. Causes of Death If cursory research is to be trusted, the Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson was populated by close friends who slaughtered animals and served alcohol for a living. When this living ended for each individual, however, the causes varied. It should be noted that 65 of the 142 burials (45%) in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb were for children under six years of age. The Fortassin family, who buried five children in this tomb, were by no means unusual in their parental grief. Joseph Bararre and his wife Amanda Mailhes buried four children as well, all of whom were interred in vault 8. The high concentration of child burials in this tomb has a dual explanation. In addition to the well-understood status of childhood illness and mortality in the late nineteenth century, it was also much more likely for a family to bury a child in a society tomb than one built for a family. Married couples without their own family tomb were unlikely to purchase a lot for the burial of a child or stillborn infant. Instead, it was much more affordable to inter the child in a wall vault or society tomb, if available. Furthermore, the spiritual and emotional benefits of society-supported burial of a child were likely comforting. A significant percentage of the 65 infant/child burials were the stillborn or nonviable infants of society members. The other children of the Sociètè died of many common childhood maladies, including lockjaw (tetanus), cholera, croup, seizures, and whooping cough. Six children were listed as having died either of “bad teething” or a jaw ailment. In the nineteenth century, a range of many ailments was attributed to the process of teething in toddlers, including intestinal disease, seizures, meningitis, or even crib death. About half of the burial records in the Sociètè burial book list a cause of death. Among the adult members, most causes of death of typical of the time period: apoplexy, Bright’s disease, consumption (tuberculosis), and yellow fever. Surprisingly, only four burial certificates mark yellow fever as cause of death. This statistical anomaly may be explained by society members being buried hastily during times of epidemic, either in other tombs or too quickly to fill the burial form completely. “A Mort et Sans Espoir de Guerison” A few members, however, appear to have died in a slightly more unusual manner. Among them are:

All of the above-listed men were members of the Sociètè who were buried in the Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 tomb alongside lost children, fellow butchers, and more than a few bartenders, as well as many wives, nieces, and grandchildren. A Community Buried Together Nearly all vestiges of Sociètè Française de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle de Jefferson have faded from popular memory. The tomb itself does not have a single carved name on any of its forty marble vault tablets. Yet within the decaying stucco vaults of this tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 are the relics of a great communal history that remains vitally significant to New Orleans cultural heritage. It is the hope that this research might connect the descendants of those buried in this tomb with their ancestors. The full burial rolls of interments into this tomb from 1872 to 1900 (up to the society’s merger with Sociètè Française d’Assistance Mutuelle de Nouvelle Orléans) have been uploaded to FindaGrave, in hopes their descendants may find them. The burial books are also available as an Excel Spreadsheet , MS Access Database, or PDF Document. Click here for burials listed by vault number. [1] Unless otherwise noted, all content is referenced directly from the original burial books as transcribed and documented by Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Links to these materials can be found at the end of this blog post.

[2] Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon, editors. Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1992), 112. [3] Edwards’ Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans, for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company 1872), 366. [4] New Orleans City Directory 1870, 531. [5] State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History. Vital Records Indices. Baton Rouge, LA, USA. [6] Times-Picayune, August 28, 1927, 2. [7] Times-Picayune, January 18, 1929, 2; [8] To our knowledge, if this family is related to Guillaume Tujague, restauranteur, it is only distantly. [9] Alternately spelled Moledous, Mouledoux, etc. [10] Pierre Lacaze, also from Trie, witnessed Sylvain Tujague’s final will in 1882. Louisiana Will Book, Vol. 21 (1880-1883). [11] “City Litigation,” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, May 30, 1869, 5. In this article regarding the Butchers’ filed injunction against the City, the author notes their injunction as “a string of reasons as clear and cutting as the keenest cleaver could demonstrate.”

1 Comment

2016 is already shaping up to be a great year for Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. More than ever before, we’ve had such exciting opportunities to share our research and knowledge of New Orleans cemetery preservation with others. This week, we presented to the Louisiana Historical Association annual conference in Baton Rouge. If you enjoyed this presentation (or if you missed it) you can catch us at these upcoming speaking events and volunteer opportunities.

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC will also be participating in a number of presentations this year. On June 1-4, we will be participating in the national conference of the Vernacular Architecture Forum (VAF), in Durham, North Carolina. There, with Dr. Peter Dedek of Texas State University, we will present to conference attendees on the contribution of African American labor organizations to the architecture of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. If you can’t make it to North Carolina, you can check out our brief synopsis on the topic here. On September 15, Oak and Laurel will have the great pleasure of presenting to the Italian American Cultural Center. In this lecture, we will discuss the impact of Italian Americans on our New Orleans cemetery landscapes. Learn more here. There are some other events coming up that we can’t wait to attend! On Saturday, April 16, author of recently published New Orleans cemetery opus Death Embraced, Mary Lacoste, will present to the conference of the International Cemetery, Cremation, and Funeral Association in New Orleans. The conference will be a great gathering of professionals in the funerary industry, and we’re excited to see Mary bring some New Orleans flavor to the event. Death Embraced is available at many local New Orleans bookstores, as well.

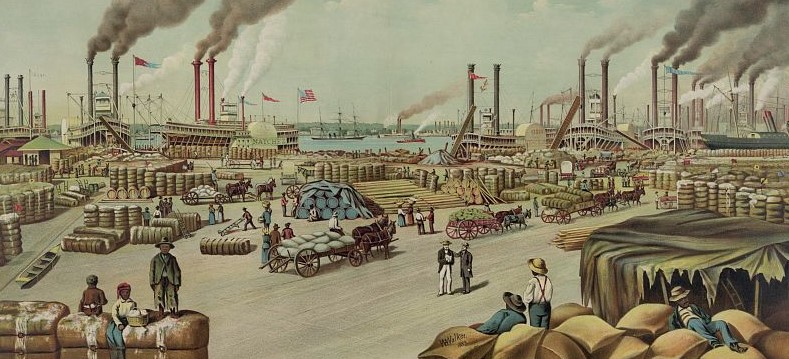

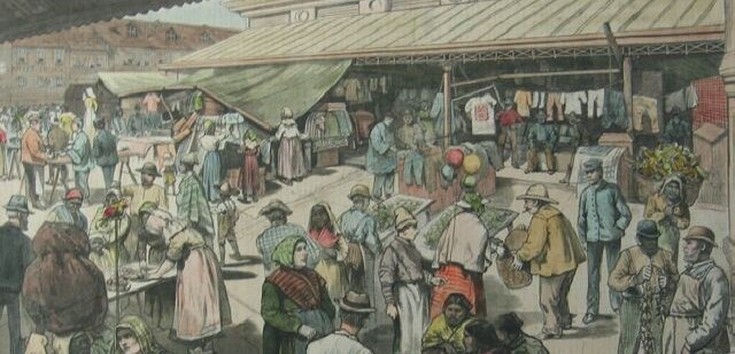

On April 27, we’re looking forward to seeing Dr. Daniele Maras of Columbia University present at Loyola University in a lecture entitled, “A Way to Immortality: Greek Myths of Divinization and Etruscan Funerary Rituals.” Check out details here. 2016 is going to be a great year for cemetery and funerary scholarship and research in New Orleans. We’ll see you out there among the tombs! Labor Day was established in the 1880s as a holiday in which to appreciate and remember the contributions of organized labor in our communities. New Orleans is not always readily associated with labor history, but one walk through a quiet, historic cemetery and the significance of workingmen’s societies is clear. Established in 1850 along Washington Avenue at Saratoga Street, Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 is the site of many different expressions of the drive of individuals to organize and collect for the greater benefit. Social aid societies such as the Société Française de Bienfaisance et D'Assistance Mutuelle built tombs for their members here – tall, wide, multi-vault tombs into which numerous burials could be made at once. Members of these societies paid monthly or yearly dues, the benefits of which included a funeral, tomb burial, and often monetary support for widows and orphans. The most prominent of these societies in both history books and the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 is that of the Butchers’ Benevolent Society, who contracted James Hagan and L.E. Lohes to build their eighty-seven vault tomb in Square 19. It cost $5,000 and was completed in 1868.[1] The Butchers’ Benevolent Society charged its members each $1 in the event of a member’s death, the proceeds of which were given to surviving family. If any member failed to attend the burial of the deceased butcher, he was fined fifty cents (one dollar for board members). Members attending a butcher’s funeral were prohibited from smoking cigars and cigarettes while processing to the tomb, but were allowed to do so when processing away.[2] The Butcher’s association tomb is distinctive, but is not nearly the most significant aspect of the society’s history. Shortly after the dedication of the tomb, the Butchers’ Benevolent Association brought suit against the City of New Orleans in a case that challenged the interpretation of the newly-drafted Fourteenth Amendment. The Slaughterhouse Case became a landmark Supreme Court case in 1873, and continues to be argued and revisited today. The Slaughterhouse Case challenged the language of the Fourteenth Amendment, which was intended to establish the rights of emancipated slaves as the same rights, privileges and immunities of all American citizens. Beyond the Butchers’ tomb, the exercise of these rights by African American laborers is visible in high relief across the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. African-American Labor Societies Along the Sixth Street and Loyola Street fences of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 are numerous society tombs dedicated to the members of African American labor organizations. Many of them were associated with the transport, weighing, and moving of goods along New Orleans’ waterfront: the Coachmen Benevolent Association, the Teamsters and Loaders Union Benevolent Association, the Cotton Yardmen No. 2, and others. In the late 1870s and through the 1880s, these associations formed to protect the rights and opportunities available for African American workingmen. Organizations were racially segregated but frequently worked in tandem with white organizations. The Cotton Yardmen Benevolent Association No. 2 is an example of this. From Eric Arnesen’s Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: “Leading the new union drive was the white Cotton Yardmen’s Benevolent Association formed in December 1879 under the direction of Democratic party ward boss and Administrator of Police, Patrick Mealy; two years later it boasted a membership of 986 and a bank account of $13,000. Black cotton rollers, with the assistance of the leaders of the white yardmen, formed the Cotton Yardmen’s Benevolent Association No. 2, in January 1880, and both organizations agreed to work ‘in full harmony’ with each other. In April 1880, the black teamsters and loaders established their benevolent association, as did coal wheelers the following month…In September 1880, cotton weighers and reweighers formed a mutual aid association that aimed to secure a uniform system for weighing and re-weighing cotton and to regulate wages and arbitrate disputes.[3]” Organizations like those represented in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 navigated the twin hardships of labor injustice and racial prejudice. Yet the establishment of such unions was accomplished, despite acute awareness of the possibility of violence. Events like the 1887 Thibodaux Massacre and other bloody labor conflicts would have surely weighed upon laborers as they worked toward fair treatment.

While these treatments appear to offer a maintenance-free solution to crumbling tombs, such materials can be harmful to the soft brick beneath. Of the twenty-two society tombs of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, only a few are not abandoned, and active decay is the dominant force.

This Labor Day, we take part in the intention of this memorial architecture and appreciate the achievements that the society tombs of Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 represent. For further reading: Daniel Rosenberg. New Orleans Dockworkers: Race, Labor, and Unionism 1892-1923. New York: SUNY Press, 1988. Eric Arnesen. Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: Race, Class, and Politics, 1863-1923. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994. Steve Striffler and Thomas Jessen Adams. Working in the Big Easy: The History and Politics of Labor in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: University of Louisiana Press, 2014. Paul D. Moreno. Black Americans and Organized Labor: A New History. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008. PBS: Landmark Supreme Court Cases related to Labor. New Orleans Dockworkers and Unionization, Wikipedia New Orleans 1892 General Strike, Wikipedia [1] New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1868, 1; “The Butchers’ Benevolent Association,” New Orleans Crescent, October 13, 1868.

[2] Butchers’ Benevolent Association, Constitution et règlements de la Société de bienfaisance des bouchers de la Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans: Imprimerie Franco-Americaine), 1883, Articles Fourteen and Sixteen. [3] Arneson, Eric, Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: Race, Class, and Politics, 1863-1923 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 61-63. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly