|

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb.

2 Comments

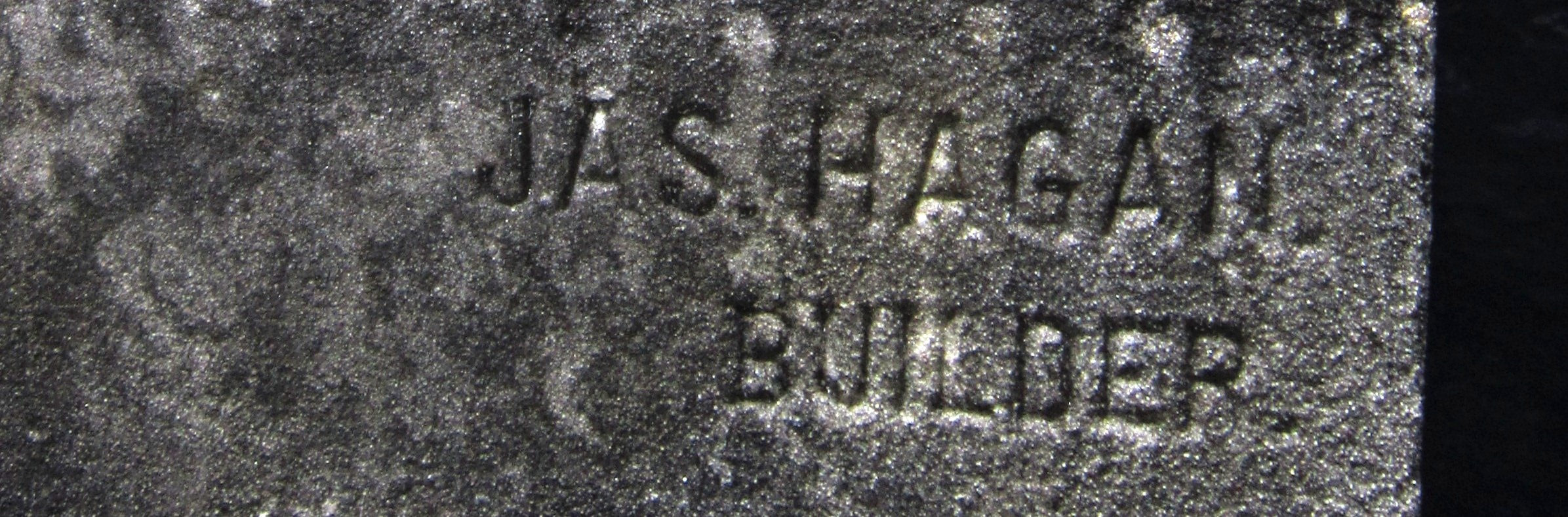

Irish-born Hagan was a state senator, a stonecutter, a real estate developer, and a dock commissioner in his long life, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was deeply shaped by his work. Along the main aisle of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, a pink granite tomb stands out from its lime-washed, marble-clad neighbors. Surrounded by a cast-iron fence, the tomb of James Hagan and John Henderson is often noted as the last resting place of a stonecutter whose work is prominent elsewhere in the cemetery. Yet this note, and the carved name of James Hagan, is only one small detail in the larger story of James Hagan’s life. James Hagan was not only a stonecutter but a real-estate dealer, state senator, community leader, and politician. He lived and worked in New Orleans not only in a time of great social change but a period of high craftwork and architecture in the city’s cemeteries. Among his signed works are some of the most ornate in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, all marked by detailed stonework and expensive marble cladding.[1] Sources suggest that James Hagan built the pink granite tomb not for himself but for his first wife, Mary Henderson, after her death in 1872. Hagan married Mary Henderson in New Orleans shortly after he immigrated from County Armagh or County Antrim, Ireland, in approximately 1852.[2] James Hagan and his brothers John, Peter, and Patrick, as well as their mother, all fled Ireland in the 1850s after famine likely forced them to emigrate. In the Fourth District of New Orleans, formerly the New Orleans suburb of Lafayette, the Hagans joined thousands of other Irish who had formed a community along the banks of the Mississippi River in the neighborhood now known as Irish Channel.

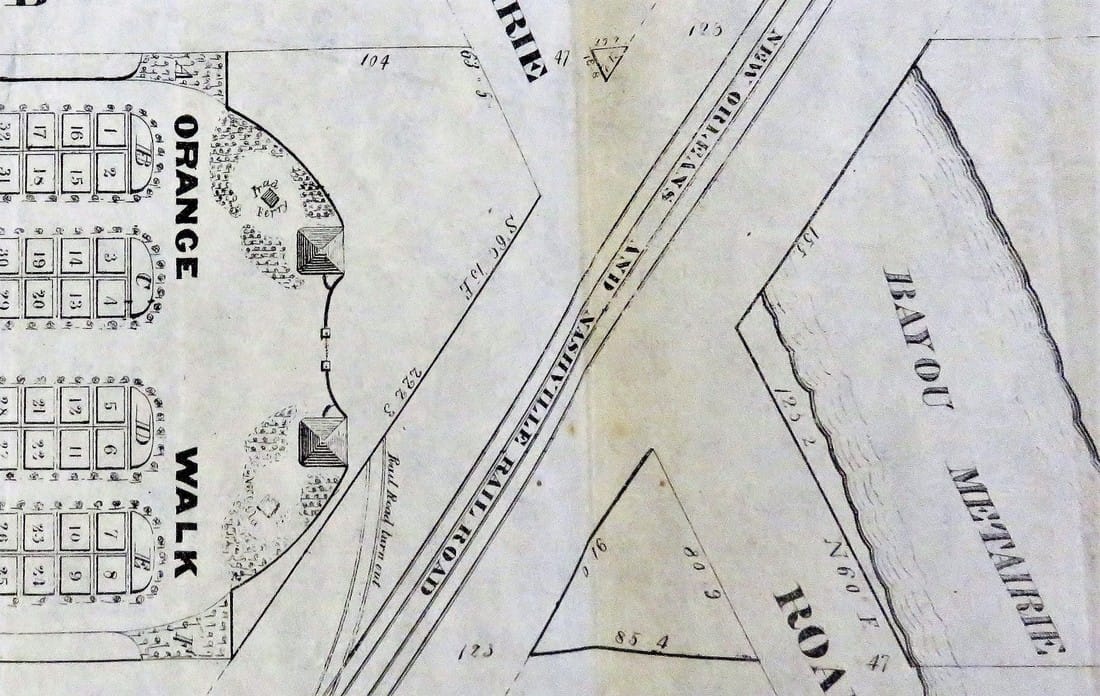

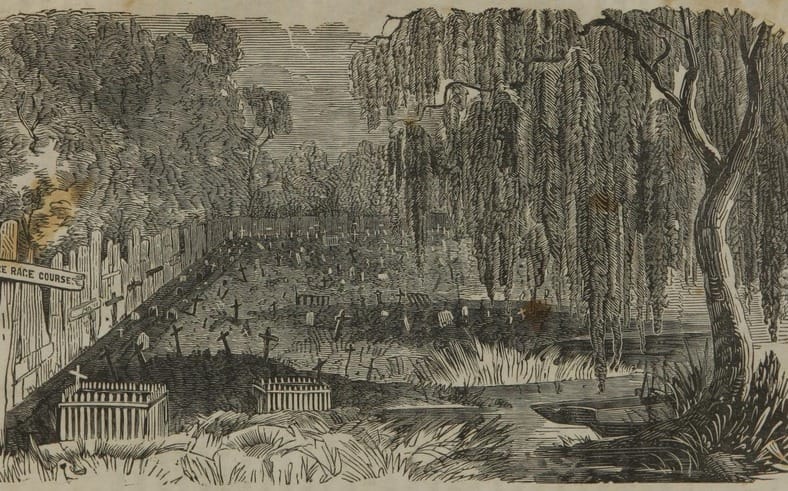

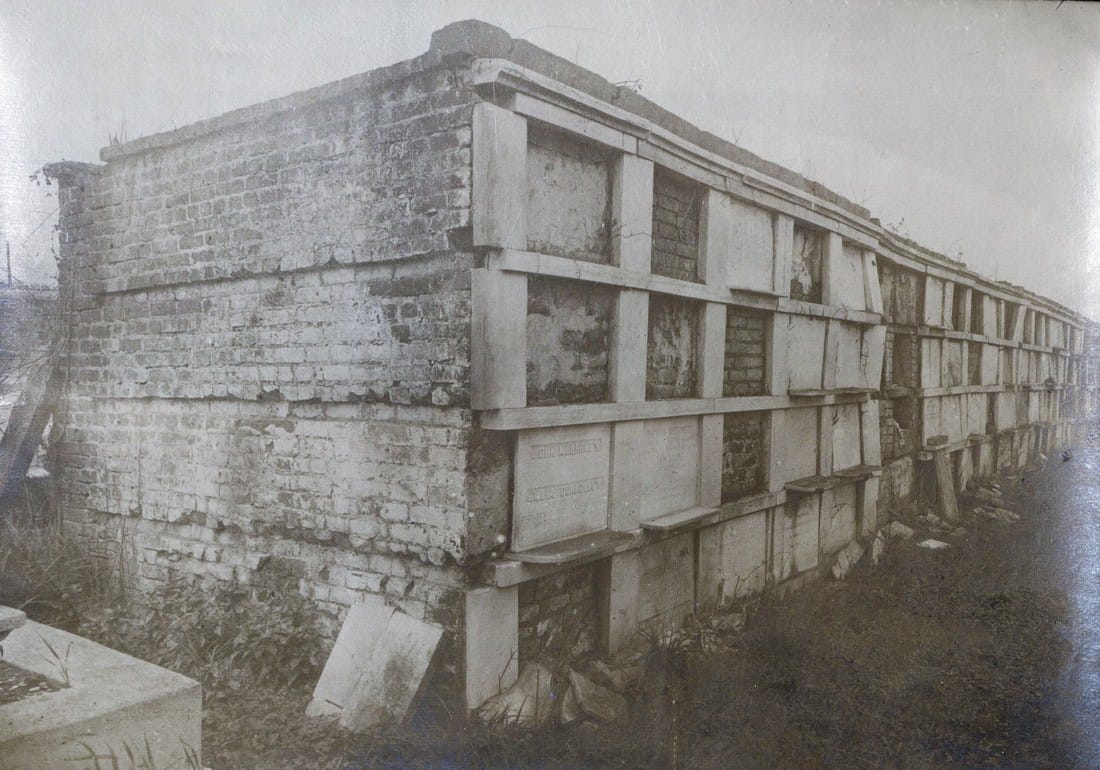

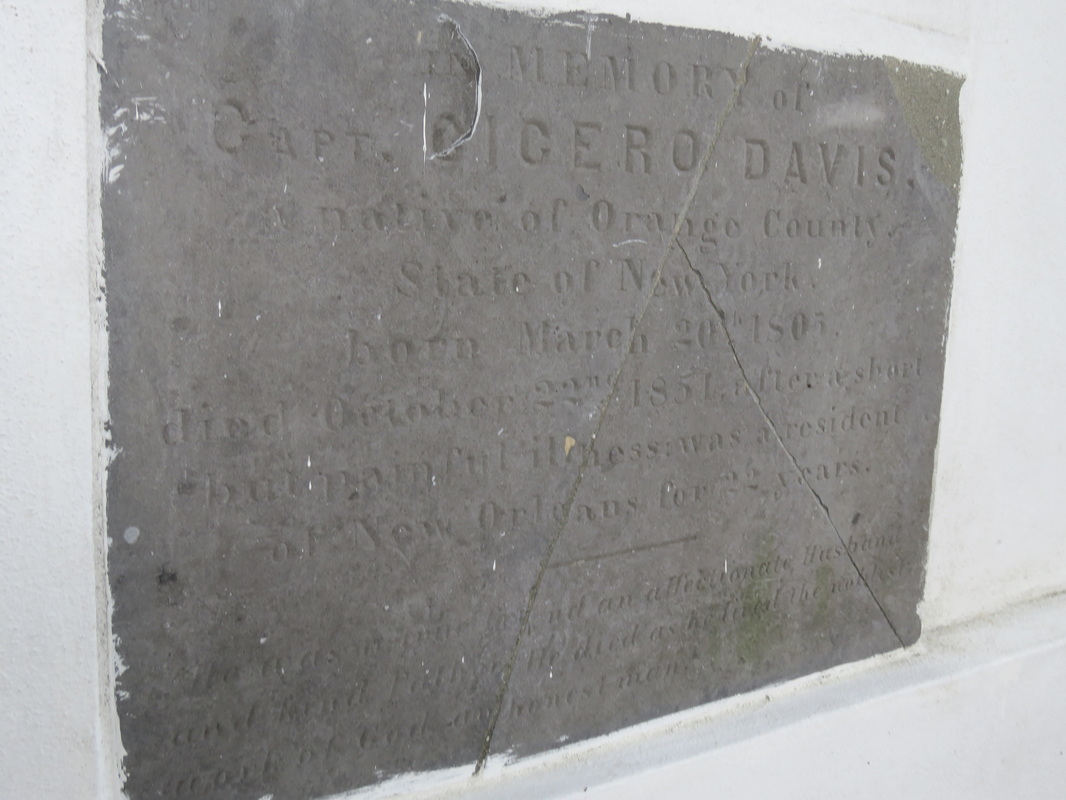

Part Two of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. Find Part One here. In the 1840s, Cypress Grove Cemetery developed into the landscape its founders envisioned: tree-lined and populated with tombs of the finest order. It also gained company as St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest were all established between 1840 and 1850. There at the corner at what is now Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Cypress Grove was part of a pastoral scene: barges floating up Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal, visitors strolling the gardens at the Halfway House, and rail cars pulling up right to the cemetery gates, unloading mourners and the bodies of the mourned.[1] Between its founding in 1840 and the turn of the century, Cypress Grove would become the final resting place of many famous and infamous New Orleans characters. Northern-born transplants to the city would combine New Orleans tomb architecture with the styles and materials they were accustomed to. Firemen would memorialize their fallen brethren within the cemetery’s marble-clad walls. Much of the incremental detail of the cemetery at its height, though, has weathered away from its present-day appearance. It’s easy to miss this historic garden cemetery for its modern lack of trees. But with historic research and a keen eye, it’s possible to rediscover Cypress Grove’s historic grandeur. Firemen, Northerners, and Protestants Cypress Grove was the first fraternal cemetery in New Orleans. All other cemeteries founded up to 1840 belonged either to the Catholic parishes (except Protestant Girod Cemetery, belonging to Christ Church Cathedral) or to each respective municipality (i.e. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1). Many other fraternal organizations, including other firemen’s organizations, would found their own cemeteries over the course of the nineteenth century. Cypress Grove was not intended for the exclusive burial of firemen. It served all New Orleanians seeking burial, if they could purchase a plot, and many who could not. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (present-day Canal Boulevard) was contracted by the City of New Orleans for indigent burial, even after Charity Hospital Cemetery was established in 1848.[2] While Catholics in New Orleans had many cemeteries from which to choose, Protestants had only Girod Street Cemetery and the municipal cemeteries. Perhaps it was simple economics that caused so many Northern-born Protestants to buy property in Cypress Grove. It may also have been caused by cultural interaction between the Firemen (many of whom were also non-native New Orleanians) and others who joined them as newcomers in the Crescent City. In any case, the great majority of historic burials in Cypress Grove denote birth in northern climes such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and others. The Firemen’s Charitable Association fell into this market easily. Stonecutters whose work featured mostly in Girod Street Cemetery, such as long-time Girod Street sexton Horace Gateley, executed tombs and tablets in Cypress Grove as well. Gately himself, who drowned in at Isla del Padre, Texas in 1867, is buried in adjoining Greenwood Cemetery. The FCA even advertised in-ground burial in Cypress Grove. While in-ground burial occurred in nearly every cemetery in the city, FCA was the only cemetery owning body to advertise it – plainly appealing to newcomers with a distaste for Continental-inspired above-ground tombs.[3] When Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957, Cypress Grove became a de facto artifact of what the Protestant cemetery may have looked like. Simpler, sarcophagus-style tombs with accents placed more on great obelisks and sculpture than on Greek acroteria or Baroque scrollwork dotted the aisles of both Girod and Cypress Grove. What few photos of Girod Street Cemetery remain even suggest a few duplicate tombs between both cemeteries: including the now headless and armless tomb statue and tomb of Henrietta Sidle Davidson (died 1881) and another tomb in Girod Street. Philadelphia brick, New Hampshire granite, and other Anglo-inspired tastes contributed to the budding landscape of Cypress Grove.

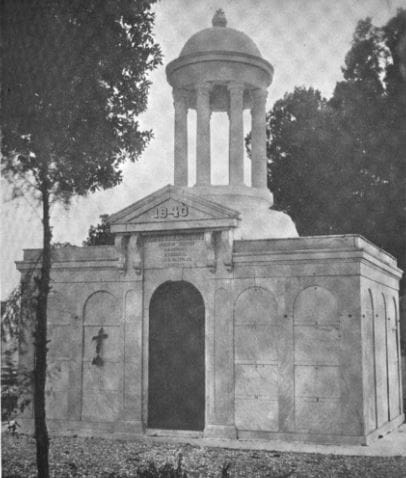

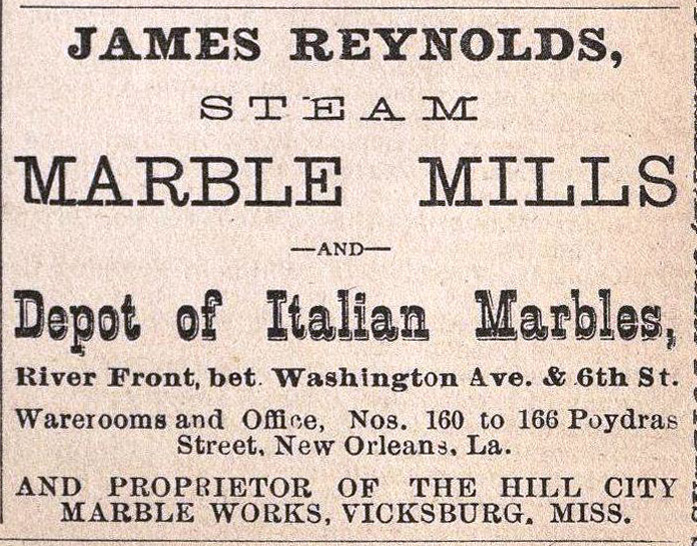

Mr. [S.T.] Jones placed a closely sealed bottle in the box, containing the constitution and list of members of this efflisient [sic] company, the daily newspapers of the city, and the various coins of the country. This was also embedded in mortar, the cover put on, and the whole covered with solid masonry, upon which the corner stone was laid. The beauty of the day, the solemnity of the occasion, and the mournful memories engendered by the scenes around, all contributed to give the ceremony a peculiar interest.[5] The tomb of Perseverance Lodge No. 13 dominated the entrance of Cypress Grove Cemetery then as it does now – a large terra cotta cupola with ionic columns and a cast-iron finial at its dome was constructed atop the tomb roof. At the center of its primary façade, an entrance was likely constructed which was enclosed by cast-iron doors. Above this door were marble brackets and a Classical pediment. The tombs of Philadelphia Fire Engine and Eagle Fire Company were tucked into the front corners of the cemetery. Each built identically, with marble-clad masonry and large urns and finials, they were each enclosed with iron gates, each within the line-of-sight of the Irad Ferry monument. Masterpieces in Marble and Granite Other societies in addition to fire companies would build their tombs in Cypress Grove, most notably the Chinese tomb and Baker’s Benevolent Association tomb. But Cypress Grove would make its mark in the number of great family tombs that populated its aisles. The sarcophagus tomb is one of the most notable artifacts of funerary architecture in New Orleans cemeteries, and in Cypress Grove this was no different. Built of brick and clad in marble pilasters, cornicework, and sculptural elements, the sarcophagus tombs of the McIlhenny, Davidson, Johnston and Walker tombs are examples of the dozens of this burial type found in Cypress Grove. Built by stonecutters like Anthony Barret, James Reynolds, and Newton Richards, they represented the English-speaking stonecutter’s take on a burial style often associated with Creole artisans. The French-speakers were present in Cypress Grove, as well. Sarcophagus tombs by signed by Florville Foy are present beside the work of New Orleans-born Jewish stonecutter Edwin I. Kursheedt. Renowned French-born cemetery architect J.N.B. de Pouilly designed two of the best-known tombs in Cypress Grove: those of Maunsel White and Irad Ferry (constructed by Monsseaux and Richards, respectively).

The only remaining example of this style of historic tomb construction lies not in Cypress Grove but in Metairie Cemetery – the Duverje family tomb, constructed between 1808 and 1820 and moved from the family cemetery in Algiers in 1916, retains such acroteria. They are the last of their kind in New Orleans cemeteries. Then and Now After 1945, New Orleans cemeteries underwent a seismic shift in management, industry, and trade. The monument industry had been slowly becoming a national affair managed by large companies – a shift that reached New Orleans after World War II. Over the years, most cemeteries abandoned the employ of the cemetery sexton who traditionally cared for the grounds on a daily basis. Stonecutters, who had often served as sextons, adapted and became cemetery owners and dealers of nationalized products. Technology changed the way tombs were built, repaired, and maintained. This shift affected every cemetery in New Orleans. In the Catholic cemeteries, it led to the consolidation of parish burial grounds into the incorporated New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. In municipal cemeteries, it meant a transfer of management to overstretched city departments that cared for publicly-owned buildings and parks.[7] In the fraternal cemeteries, it meant a consolidation of duties and a new focus on sellable space to accommodate budget shortfalls.[8] With population movement to the suburbs and elsewhere, tombs were less likely to be cared for by their owners. With no sexton to manage the landscape, small issues with tombs became larger problems, often solved in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Storms like Camille, Betsy, and Katrina flooded Cypress Grove Cemetery, killing many of the surviving trees. Those who entered the monument trade after 1950 were much more familiar with new technologies than old materials. Old problems, then, were solved in new ways. In the 1960s, when the marble facing of the extensive wall vaults at Cypress Grove began to sag away from their brick substrate, the decision was made to remove the marble instead of repair it. When landscaping tumuli was too labor intensive, the sod was stripped from their structures, leaving cement-patched, igloo-like bodies behind. Herbicides like RoundUp were selected to replace arduous mowing, damaging masonry and causing grassy root structures to erode, leaving deep ruts which can destabilize walls and tombs. Alternately, trees which lent such a rural feel to Cypress Grove eventually overgrew their root structures, tipping walls and capsizing tombs. All the while, the responsibility of families to care for and repair their own cemetery property became anachronistic in an era of new innovations and perpetual care. The cultural forces that created Cypress Grove had transformed, with the role of the fraternal society somewhat supplanted by the rise of Social Security and insurance companies; the rural cemetery now firmly at the edges of the metropolis. New Orleans cemeteries in general are prized for their historic value, but the value of their maintenance and preservation may exceed that interest from many sides. Yet Cypress Grove remains, its Egyptian columns rising above Canal Street and City Park, where once the bayou and the railroad met. It may be difficult to see it, but with a conscientious eye and a little history, its lost landscapes can be found. [1] “Passenger and Freight Barges on the New Canal,” Daily Picayune, January 1, 1846, 4; Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louis Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Press, 2004), 30-35; At least one duel also took place in front of Cypress Grove’s gates, between former state senator Waggaman and a former New Orleans mayor Prieur, Daily Picayune, March 11, 1843, 2.

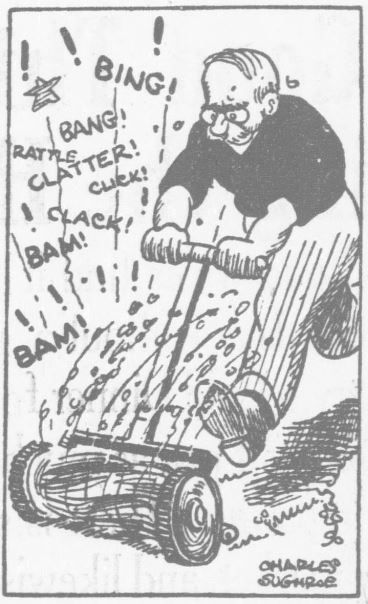

[2] Daily Picayune, April 21, 1846, 2. [3] “Cypress Grove Cemetery,” Daily Picayune, September 15, 1842, 2. Full text: “CYPRESS GROVE CEMETERY. A portion of this rural cemetery having been appropriated for interments in GRAVES, application can be made at the Firemen’s Insurance Office; to M.C. Quirk & Sons, or Mr. Monroe, Undertakers. The Superintendent will also receive at the ground any corpse for interment, on payment of $5 for grown persons and $3 for children. GEORGE BEDFORD, President F.C.A.” [4] “Grand Fancy Dress Ball,” Daily Picayune, February 26, 1852, 3; “Fireman’s Funeral,” Daily Picayune, August 14, 1847, 2. [5] “The City: An Interesting Ceremony,” Daily Picayune, January 3, 1854, 1. [6] Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1855 (New Orleans: Printed at the office of the Picayune, 66 Camp Street, 1855), xiv. [7] Pie Dufour, “Old Cemetery Getting New Look,” Times-Picayune, November 10, 1968. [8] In Cypress Grove, sexton and stonecutter Leonard Gately was instrumental in developing sections into sellable space. Daily Picayune, April 12, 1959, 154. To call any cemetery landscape “eclectic” is usually an understatement. Within cemetery landscapes are the architectural whims of uncountable individuals, families, and craftsmen. And so it goes that in New Orleans cemeteries we pass a Gothic chapel and find a Celtic cross. Our landscapes are amalgams of recollection – Classical Greek, Roman, and Egyptian are at home with the Italianate, the Moorish Revival, and the Art Nouveau. This rich tradition has inspired architects to look backward for inspiration, but there is no farther backward one can reach than the tumulus. Known also as a barrow, the tumulus is a burial structure that rises from the ground as a hill or mound. Often, the tumulus bears a means of access from the side or top of the hill. Its origins span across the ancient world, both Old and New, representing a common type of burial shared between the ancient Norse, Etruscans, Chinese, Native Americans, and many, many more.[1] This type of burial also has its home in New Orleans cemeteries. The Elks Lodge tumulus in Greenwood Cemetery, and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia in Metairie Cemetery are often used as examples for the tumulus in modern cemeteries. Yet they are not alone in their unique appearance. The tumulus once graced many more New Orleans cemetery landscapes than it does today. In this blog post, we explore the origins, proliferation, and eventual disappearance of the tumulus in New Orleans cemeteries. Mounds, Barrows, and Antiquarians In Europe, mound, barrow, or tumulus burial was practiced by pre-Roman and Roman cultures. Tumuli can be found in nearly every European country – today as protected archaeological sites and heritage attractions.[2] The practice of mound burial was abandoned after the rise of Christianity and the development of churchyards in Europe. Until the cemetery landscape was reinvented by the rural cemetery movement in the early 19th century, the tumulus was a thing of ancient history. A number of factors contributed to the reintroduction of the tumulus to cemetery landscapes in Europe and the New World. With the establishment of cemeteries like Pere Lachaise in Paris, the understanding of cemetery landscapes shifted into one of green space and architectural eclecticism. From this cultural development sprang the Greek Revival architecture that proliferated New Orleans thanks in part to J.N.B. de Pouilly. But the gaze of nineteenth century Europeans and Americans did not exclusively look back to Greece. It turned to Egypt and the Middle East. It incorporated Gothic spires into new designs. And it looked even farther back to the mysterious mounds found in the European countryside. By the 1870s, the antiquaries of Europe excavated numerous tumuli in England, Italy, France, and Norway. Such discoveries were commonly featured in New Orleans newspapers.[3] An awareness of the burial mounds of great ancient cultures joined Greek temples and Gothic cathedrals in the consciousness of New Orleaneans. Furthermore, the people of the American South were familiar with mound burial in their own backyards. The presence of seemingly abandoned mounds in the southern and mid-western United States had captured the interest of Europeans since Hernando de Soto reported their existence in 1541. After colonization and into the nineteenth century, some of these mounds in Louisiana were repurposed by Americans for use as their own cemeteries. This was the case in Monroe’s Filhiol-Watkins Cemetery. Fleming Plantation Cemetery is also located on a Native American mound. By the mid-nineteenth century, mound burial was firmly rooted in the imagination of New Orleaneans. From these inspirations, the tumulus made its debut in cemetery landscapes. The Tumulus in New Orleans Like the city itself, New Orleans cemeteries are the product of many layers of community and identity. Each cemetery is a reflection of the people who made it their own. Cemeteries that were built and utilized by Irish, German, or American New Orleaneans developed with a different aesthetic than those shaped by French speakers. Each community drew upon their own culture and style to create their cemetery. The tumulus entered the popular consciousness in part via a new interest in archaeology and ancient architecture.[4] Though tumuli in New Orleans often had Greek Revival motifs, they were utilized by Americans elsewhere in the United States. Great northern cemeteries like Mount Auburn featured tumuli as part of their cultivated agrarian landscapes, as did closer cemeteries in Charleston and Savannah.[5] Thus, it is no surprise that tumuli in New Orleans appeared first in American and not Francophone cemeteries – decades before the Elks, the Army of Tennessee, or the Army of Northern Virginia. Tumuli are found primarily in the Canal Street cemeteries, including Cypress Grove, Masonic, Odd Fellows Rest, and Greenwood. They are also found in American-oriented cemeteries like Lafayette Cemeteries No. 1 and 2. There are dozens of tumuli to be found in our cemeteries, yet the untrained eye will not find one. Hidden Tumuli, or How the Lawnmower Changed Everything Most tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries no longer look like tumuli. Stripped of their grassy hill features, they appear instead simply as unusual tombs with rounded bodies. The Hornor and Holdsworth tumuli in Cypress Grove and Masonic Cemeteries (respectively) are good examples. Both constructed with a marble primary façade featuring relief carvings of cut flowers, they were likely carved by the same craftsperson, although neither structure is signed. Both tumuli have conspicuously rounded structures that seem to contrast with the grandiose style of their primary face. Yet when imagined as they originally appeared, as green hills from which their marble faces projected, their aesthetic comes together. There are many former tumuli in New Orleans cemeteries that have been stripped of their signature mounds. The John P. Richardson tomb, located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, was described in 1885 as “enclosed in a tall oval mound of turf, with marble doors set in a stone frame.”[6] The tumulus memorialized Richardson’s young daughters – Ella and Marguerite Callaway or “Calla,” ages six months and four years old. This original appearance could certainly not be deduced from examining the Richardson tomb today: its sweeping marble doors and arched primary face are attached to what appears to simply be a brick-and-mortar tomb. Dozens of former tumuli can be found in New Orleans cemeteries; most are identified by the slightly unusual appearance of the tomb body when compared to its front. Nineteenth century tumuli were designed to appear monumental in both mass and detail, with their entrances featuring sweeping side elements or rounded tops. The massive hill that comprised the tumulus body framed these features. Other examples of former tumuli include:  McIntosh tumulus, Cypress Grove Cemetery. In November 1873, the Nixon (now McIntosh) tomb was described as: "in the form of a mound overgrown with grass, with a large marble front. Along the top of the slab creeps an ivy, which will eventually cover the whole mound. The frontispiece was garnished on each side by a vase of white flowers." (New Orleans Republican) The disappearance of historic tumuli can be explained in the same way many other landscape features have been altered. As cemetery design, economics, and management changed, the tumulus was viewed as far too costly to maintain. Before the 1920s, cemeteries featured cultivated grounds with aisles paved in crushed shells – and they were manicured using manual, spiral-bladed lawn-cutters. Between 1920 and 1945, new lawnmowing equipment was patented with small gas-powered motors, cutting down on the labor required for landscape maintenance. This innovation was later supplemented by the availability of ready-mix concrete with which to pave once shell-strewn aisles. Finally, in the 1940s, industrialization of the monument and funerary industries led to most cemeteries eliminating the position of sexton (caretaker) from their ranks.

Each tumulus memorializes the fallen Confederate soldiers and deceased veterans associated with each division. After the Civil War, veterans of both Confederate and Union armies formed such benevolent associations for the support of their members. In the case of the Armies of Northern Virginia and Tennessee, perhaps the tumulus design was a nod to the military and fraternal connotations many ancient tumuli bear. Each tumulus features a remarkable sculpture at its hillside apex. The Army of Northern Virginia tumulus supports a 38-foot column atop which a sculpture of General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson stands. The Army of Tennessee features an equestrian bronze, sculpted by Alexander Doyle, depicting General Albert Sidney Johnston atop his horse, Fire Eater. Both tumuli are notable features of Metairie Cemetery, included in most histories of the cemetery.[7] The third notable tumulus in New Orleans is viewed daily by many city commuters. The tomb of the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, Lodge 30, features a bronze elk standing atop its grassy summit. The tumulus is located in Greenwood Cemetery at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, where the elk looks out above the traffic. The Elks lodge tumulus was first conceived of in 1911 by the local Elks, who held a great circus in downtown New Orleans to raise funds for the cause. In subsequent years, the Elks would commission monument man Albert Weiblen to construct the tomb at the cost of $10,000 (approximately $250,000 in 2016 currency). The structure was assembled of Alabama granite, shaped with a classical pediment, the center of which features a clock forever frozen at the eleventh hour, a reference to the “Eleventh Hour Toast” held by Elks when gathered together. Local legend has suggested that Albert Weiblen warned the Elks that the lot on which they wished the tumulus be constructed was not suitable for a structure of that size. It is true that, historically, City Park Avenue was once part of a navigation canal, an infill had only partially stabilized the soft earth. The story goes that the Elks decried Weiblen’s warning and enjoined he move ahead with construction. While primary sources for this story are nonexistent, the Elks Lodge tumulus does have a noticeable tilt toward Canal Street. Lessons in Preservation While the tumulus holds its place of honor in cemetery landscapes with the Elks and the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia, it has faded from the everyday view of most cemeteries. Such a loss is difficult to quantify. Historic New Orleans cemeteries are dynamic places where features are constantly altered, modified, destroyed, or restored. Yet as we approach the task of preserving these cemeteries as functional landscapes, the tumulus offer some distinct lessons. Stripped-down tumuli confuse the historic appearance of cemeteries like Cypress Grove and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Had these structures been preserved, their green mounds would carry on the tradition of the cemetery as garden space; and they would properly communicate the historic landscape for both grieving family and heritage tourist alike. Stripped-down tumuli are an example of one cardinal rule of cemetery preservation: that once improper treatment has taken place, it’s nearly impossible to reverse. Each blow to responsible and considerate preservation is most likely permanent. Thus, while restoration is important, maintenance, documentation, and planned preservation are much more crucial. When the cemetery landscape is understood and preserved, large-scale restorations are less necessary. Finally, stripped-down tumuli teach us to deeply consider each structure as part of a whole, to read the structure for what isn’t there as much as for what is. Through this consideration, cemetery stewards can preserve these resources of history and heritage in a responsible manner that benefits generations to come. [1] Dan Hicks, et. al. Envisioning Landscape: Situations and Standpoints in Archaeology and Heritage (Routledge, 2016), 167.

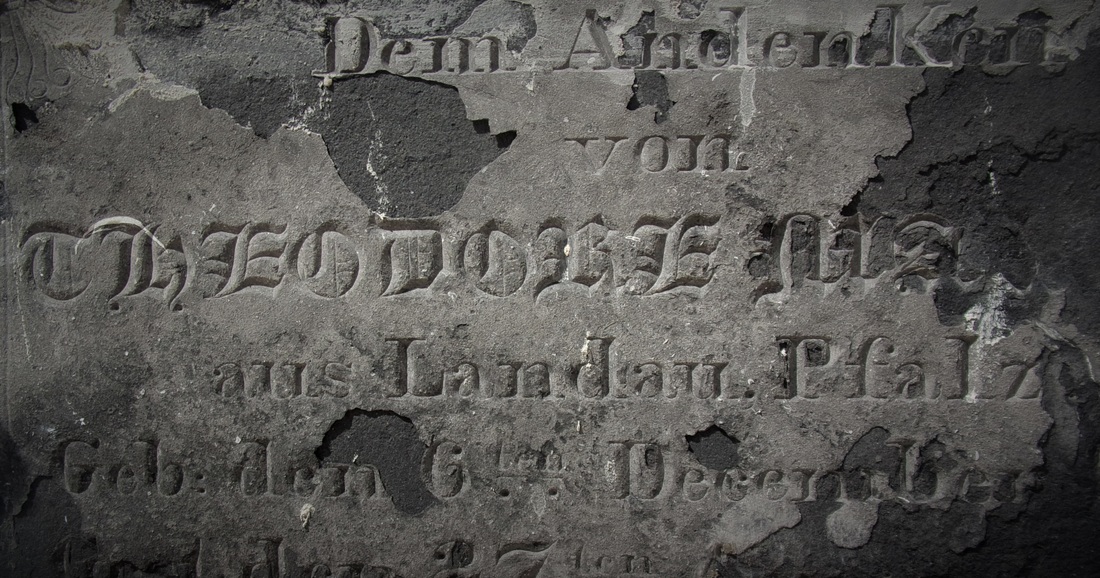

[2] James C. Southall, The Recent Origin of Man (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1875), 87-97. [3] “Jackson Mounds,” Daily Crescent, January 16, 1851; “Norwegian tumulus,” New Orleans Bulletin, April 8, 1874, 2; “Norwegian Tumulus,” Opelousas Journal, August 4, 1876, 1. [4] George F. Beyer, “The Mounds of Louisiana,” in Publications of the Louisiana Historical Society (New Orleans: 1895), 12-30. (Link) [5] Gibbes tumulus, Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, SC, and HABS documentation (Library of Congress). [6] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1885, p. 2. [7] Henri Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery, An Historical Memoir: Tales of its statesmen, soldiers, and great families (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, 1981). Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. Beyond sweeping landscapes and imposing architecture – within the “stories in stone” that are so beloved in New Orleans cemeteries, are the stones themselves. Much like the long-dead people they memorialize, these slabs of honed and carved limestone, marble, and granite journeyed great distances to become part of an irreplaceable cemetery landscape. Whose hands drew that stone from its quarry? Why is the marble found in Greenwood Cemetery drastically different from what we find in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2? Today we share the stories of quarries, infrastructures, and materials that make up New Orleans cemetery stonework. Louisiana Lacks Workable Native Stone The geology of southern Louisiana is similar to that of other states along the Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of mostly sedimentary rock, clay, limestone, and sandstone, Louisiana has few stone resources that would be desirable for cemetery monuments.[1] Furthermore, the stone that is quarried in Louisiana has historically been of poor quality for building. For example, during the 1850s construction of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., requests were made that each state donate a block of native stone to be placed in the interior of the monument. Louisiana sent a block of sandstone that, within the decade, was so crumbling and decayed that it was replaced with a block of Pennsylvania marble.[2] Thus, from the eighteenth century onward, the stone used in New Orleans cemeteries was imported from elsewhere. Various types of slate, marble, and granite were made available as trade routes and quarries opened. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans merchants and dealers offered stone from a number of different places. As time went on, the availability and sources of stone widened.

Arkansas slate was quarried from areas near the towns of Hot Springs, Little Rock, Benton, Malvern, or Mena. This small vein of quality slate, approximately 100 miles long, could produce stone of red, gray, green, or black appearance. Despite the availability of slate from Arkansas, Pennsylvania slate continued to be quarried and shipped to New Orleans. Historic Louisiana newspapers frequently mention the quality and availability of slate from the Bangor quarry in Northampton County. Given the same name as a slate quarry in Wales, the “Old Bangor” quarry had an office in New Orleans by the 1870s. Old Bangor slate is “very dark gray, and to the unaided eye has a fine texture and fine cleavage surface, almost without any luster. The sawn edge shows pyrite.” The Williamstown, Franklin, and Pen Arygl quarries of Pennsylvania also had retail agents in New Orleans, who advertised their slate to be of the same quality as that of Wales.[6]

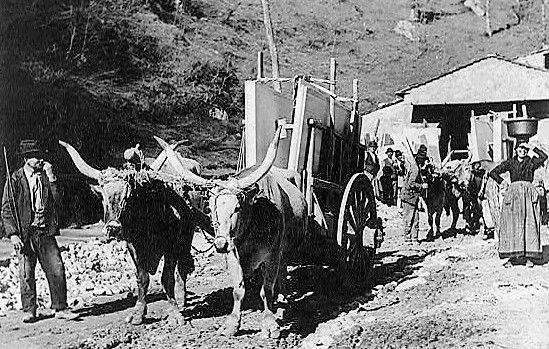

They form by the compression of these sediments, along with all the calcium-rich seashells within. They diverge when these sediments either compress and become sedimentary rock or, alternatively, are subject to higher pressures and become metamorphic. Limestone is sedimentary, marble is metamorphic. Limestone is most prevalent in the oldest remaining New Orleans cemeteries, namely St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, although precious isolated examples are found in other cemeteries. In this context, limestone was used for closure tablets. Limestone closure tablets are usually dark gray (likely quarried in Arkansas or Tennessee) and can be identified by the tiny fossilized shells included in the stone’s matrix. Around the mid-nineteenth century, whiter limestones were used in the same context as marble and are harder to identify. Some rough-faced stones that appear to be marble can be identified as limestone by spotting the shell inclusions within. These rare examples of white limestone were often quarried in Tennessee. Imported Marble: An Italian Commodity New Orleans was a primary hub for the import and export marble from both Europe and the United States. Used for closure tablets, shelves, memorial sculpture, apex sculptures, tomb cladding, and other decorative elements, marble was the medium in which cemetery stonecutters primarily worked throughout the nineteenth century. Based on documentary evidence, the quarries of Italy were the primary source of marble into the 1850s. Italian marble was either directly imported from Italy or arrived via northeastern ports like Boston or New York.[7] Florville Foy, who advertised aggressively throughout his career, frequently promoted his most recent shipment from Carrara or Genoa, cut into one, two, and three inch slabs. Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux similarly advertised his Italian marble stock.[8] New Orleans stonecutters dealt in and imported Italian marble through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, stonecutter John Hagan (active 1854 – 1890s) stocked Italian marble “for sale at a small advance on New York prices.” George Stroud (active 1866 – 1899) cut his own Italian marble at Monsseaux’s steam cutting plant. James Reynolds (active 1866 – 1880) not only sold his Italian marble in New Orleans but also in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[9] Italian marble, often vernacularly referred to as “Carrara marble” regardless of its quarry of origin, is a stone of high-grade, consistent quality, and a variety of colors including cream, pure white, and blue. As one Alabama quarry owner conceded in 1909, “Italian marble has long been a standard, not only because the stone is undeniably high grade, but also because the blocks are so uniform in quality that all the slabs or pieces from a block can be used together.”[10] The cost of importing marble in New Orleans varied over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century; at times, it actually cost less to import than marble from Vermont or Tennessee. Protective tariffs helped to stabilize the marble industry during the 1880s and 1890s, but the presence of the famed marble remained a factor among monumental craftsmen into the present. For example, in 1914, before Albert Weiblen purchased his own marble quarry in Georgia, he received a shipment of Italian marble so substantial it took two large derricks to lift the fifteen-ton blocks from the steamship in which it arrived.[11] Domestic Marble: Vermont, Alabama, Georgia, and Others The slow development of infrastructure and quarry technology prevented American quarries from competing with Italian marble in New Orleans until the 1850s. In 1845, one of the first marble quarries opened in Talladega County, Alabama. Five years later, another opened nearby, operated by J.M.N.B. Nix. Using a publicity tactic that would become common among quarry operators in the United States, the New Orleans Daily Picayune announced that “Alabama produces marble equal in fineness – that is, purity or clearness and susceptibility of polish – to any in the world, not excepting the most beautiful Italian, Vermont, or Egyptian.” It was Nix’s quarry that sent Alabama’s contribution to the Washington Monument.[12] Talladega marble can appear white, blue, or cream, and often displays black, green, or grey veins, although it is consistently characterized by the fineness of its grain. Its unpredictability in quality and appearance, however, made it costly to extract.[13] Alabama marble remained a presence among New Orleans cemetery craftsmen well into the twentieth century. One of the most recognizable and imposing monuments within Metairie Cemetery, the ornate sarcophagus of Eugene Lacosst, was crafted by Albert Weiblen from pure white Alabama marble.[14] As always, infrastructure dictated which materials were available in New Orleans at a given time period. In 1851, The Vermont Valley Railroad Company connected towns like Rutland to the greater markets in the East and South.[15] Only two years later, sources in New Orleans commented on the great productivity of the Rutland quarries, remarking that their product had gained “a reputation abroad as well as at home.”[16] Rutland and other Vermont marbles can be white, blue, or black. These quarries also produced pure-white sculpture-grade marble.[17] By 1900, Vermont produced more marble than any other American state, and the Rutland quarry was the highest-yielding quarry. Blocks of Vermont marble were sold for between $1.00 and $3.00 per cubic foot in New Orleans, where agents received shipments and distributed order throughout the South and West.[18] Like Alabama marble, marble quarried in Vermont remained in the stockpiles of New Orleans craftsmen into the mid- and late twentieth century. Vermont not only exported its marble to New Orleans, but its marble cutters as well. One account reflected that the stone cutting yards of New Orleans primarily employed skilled sculptors and polishers from the states of Vermont and Georgia.[19] By 1916, Georgia was second only to Vermont in its production of quarried marble. Although marble quarrying had existed in Georgia long before, it appears to only have gained prevalence in the New Orleans market after the Civil War. By 1888, the Georgia Marble Company in Pickens County claimed to be the largest marble quarry in the world.[20] Georgia marble is typically coarse-grained and appears in blue-gray, black, white, and Creole, which has dramatic sweeping shades of dark gray, black, and white.[21] Ubiquitous Georgia Creole Marble Between 1890 and the 1930s, Georgia Creole marble exploded in the New Orleans cemetery market and made an enormous mark on the landscape. This explosion was the result of expert marketing, improved infrastructure, and enormous supply. Modern monument men during this period utilized Georgia Creole marble in nearly every aspect of their work, from tomb cladding to headstones to vases and urns. The streamlined process of tomb building, now executed in a more “cookie cutter” style than previous generations, allowed many more tombs to be built in a short period of time, and Georgia Creole marble was the medium of choice.

Additionally, as marble is a metamorphosed type of limestone, it is naturally alkaline in quality. Thus, exposure to rain, which is naturally slightly acidic, or any other acidic substance (for example, hydrochloric acid mistakenly intended to clean the stone) will cause marble to granulate and “sugar” over time. An extreme example of marble deterioration can be found in St. Joseph’s Cemetery No. 1. The failure that likely occurred with this stone was related to moisture entrapment within the tomb itself. This, paired with the tight, compressive position of the tablet within the opening, caused the closure tablet to bow and “bubble” outward.

One of the most noticeable granite tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is that of stonecutter and sexton James Hagan. This remarkable tomb was built of red-colored Scotch granite in 1872. Around the same time, Hagan also constructed the monument of Governor Henry Allen, which was also located in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 until it was moved to the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge in the 1880s. This monument, too, was carved from Scotch granite.[24]

[1] Louisiana Geological Survey, Geology and Agriculture: A Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1902), 133-134.

[2] National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Northeast Region, Architectural Preservation Division, The Washington Monument: A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2005), 28. “Washington National Monument,” The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 22, 1850, page 1. The stone is referred to as “freestone,” meaning a soft, friable sedimentary stone. [3] Graham R. Thompson and Jonathan Turk, Introduction to Physical Geology (Rochester, NY: Saunders College Publishers, 1998), 133-137. Slate headstones are found commonly in the Northeast dating to the colonial period. Slate headstones are also present in cemeteries as far south as Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. However, no slate headstones are visible in the cemetery landscapes of New Orleans. [4] Mary Louise Christovich, Roulhac Toledano, and Betsy Swanson, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. I: The American Sector (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 1998), 57. [5] Daily Picayune, September 27, 1850, 2; Daily Picayune, May 2, 1853, 1; Daily Picayune, February 28, 1869, 11. [6] “Alexander Hill, Welsh and American Slates, Slabs, etc.” Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 4, 1875, 6. These slates priced from $6.50 to $10 per square; “Slates! Slates! Slates!” Ouachita Telegraph (Monroe, LA), July 22, 1872, 2. [7] “Brig Casket arrives from New York with sundry marble slabs,” Louisiana Advertiser, April 29, 1820, 3. “Barelli & Company, commission merchants, selling blocks of Italian marble,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1845, 3. [8] Daily Picayune, November 10, 1848, 7; Daily Picayune, February 17, 1848, 3; Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette Directory for 1851 (New Orleans: Cohen’s Directory Company, 1851), page AT. [9] Edwards’ Annual Director to the Inhabitants, Institutions….etc., etc., in the City of New Orleans for 1871 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1870), 275; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [10] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. [11] “Ship Brings Cargo of Italian Marble,” Times-Picayune, July 27, 1914, 8. [12] “Alabama Marble,” Daily Picayune, October 1, 1845, page 2; Daily Picayune, May 18, 1871, 3. [13] Committee on Ways and Means, United States Congress, “Marble: The Alabama Marble Company, Gantts Quarry, Ala., Urges Retention of Duty on Marble,” in Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908-1909, Vol. VIII (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7886-7888. In this year, cost to transport Alabama marble to New Orleans was 32 cents per cubic foot. [14] Leonard V. Huber et. al. New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 54-55. [15] Vermont Railroad Commissioner, Eleventh Biennial Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of Vermont (St. Albans, VT: St. Albans Messenger Co., 1908), 308. [16] Daily Picayune, July 15, 1853, page1; Daily Picayune, June 16, 1855, 1. [17] Thomas Nelson Dale, The Commercial Marbles of Western Vermont (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 117-122. [18] Tariff Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means, Second Session, Fifty-Fourth Congress, 1896-97, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 275-279; “Random Notes,” The Reporter: The First and Only Journal Published in the World Devoted Exclusively to Granite and Marble, No. 1 (January, 1900): 33. [19] David Spence Hill, Industry and Education: Part Two of a Vocational Survey for Isaac Delgado Central Trades School (New Orleans: The Commission Council, 1916), 227. [20] “Science and Industry,” The Colfax Chronicle (Colfax, LA), November 3, 1888, 3. This was not an uncommon claim for many quarries to make. “Georgia Quarries,” The True Democrat (Bayou Sara, LA), January 30, 1897, 7. [21] Memoirs of Georgia, Vol. I (Atlanta: The Southern Historical Association, 1895), 211-217. [22] A. Oakley Hall, “Cities of the Dead,” in Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers Tales and Literary Journeys, Frank de Caro, editor. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998), 532-533; Arthur Wellington Brayley, History of the Granite Industry of New England, Volume I (Boston: National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913), 114. [23] Ibid., 84. [24] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley of Durham University, UK, for his knowledge and expertise in identifying the Hagan tomb as Scottish granite. [25] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1895), 1095. [26] “Notes from the Quarries,” Stone: an Illustrated Magazine Vol. 4 (1892): 496. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly