|

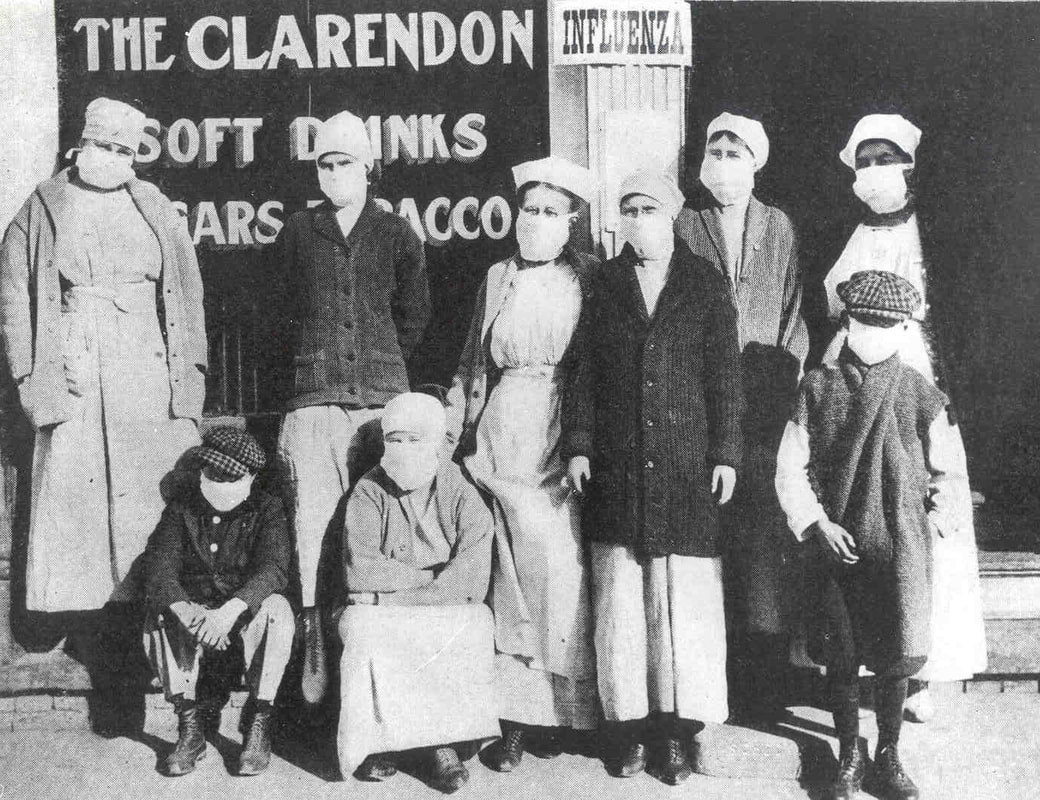

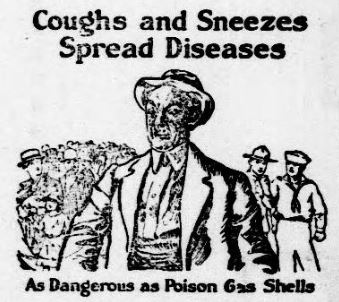

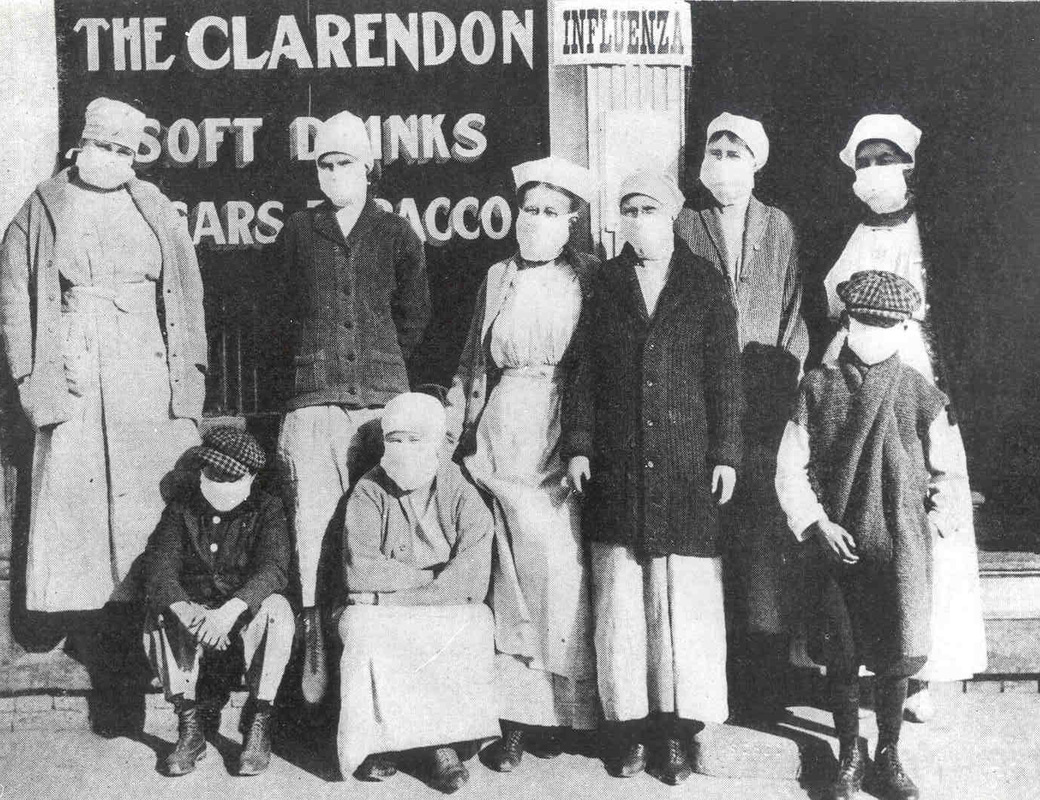

How New Orleans weathered one of the greatest plagues in history. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a worldwide emergency like that which took place in 1918. Modern-day fiction and sci-fi writers have materialized similar fears – there is no shortage of post-pandemic fiction. For example, the HBO series The Leftovers posits a world in which two percent of the world’s population has vanished, the Max Brooks novel World War Z injects zombies into a frighteningly realistic image of how civilization would handle pandemic catastrophe. The list goes on. But we so often forget that something like this did happen. In 1918, a strain of pandemic influenza swept the globe three times, infecting millions and killing five percent of the world’s population. Medical science today cannot pin down exactly where it began. One prominent theory states that H1N1 influenza began with swine farms in Haskell County, Kansas in late January 1918.[1] Like other incidents of mutated influenza virus “jumping” from livestock to humans, it could have fizzled out in the local population. Yet nationwide mobilization in response to the United States’ entry into World War I meant that military camps were ubiquitous and population movement intensified. Influenza was transported to Camp Funston, Kansas, where it spread to other camps, other towns. The first wave of influenza traveled from the United States to Brest, France, in April 1918. Within the next month, it spread to Spain. Spain, neutral during World War I, was less likely to censor press reports of the disease. Hence, although the U.S., Britain, and France saw just as many cases of influenza, such incidents were not reported. The uneven press coverage created the appearance of the disease originating in Spain, giving it the incorrect moniker “Spanish Influenza.[2]” Influenza was documented in China and India by May 1918. The spring wave, however, was comparatively mild. The second wave of Fall 1918 would be devastating. As the summer of 1918 wore on and Allied victories in Europe continued, state and federal medical officials assumed disaster had been averted.

Attempts to quarantine the sick and curb the spread of influenza were often thwarted by the pressures of total war. In one especially salient instance, insistence from upper-crust social circles in Philadelphia caused medical leaders to allow a War Bonds parade to take place, despite the mounting evidence of an influenza epidemic. New cases of the illness soared in the days after this large public gathering. In metropolitan areas, the flu jumped from military to civilian populations, and then spread.

One hundred years ago this month, influenza arrived in New Orleans.

5 Comments

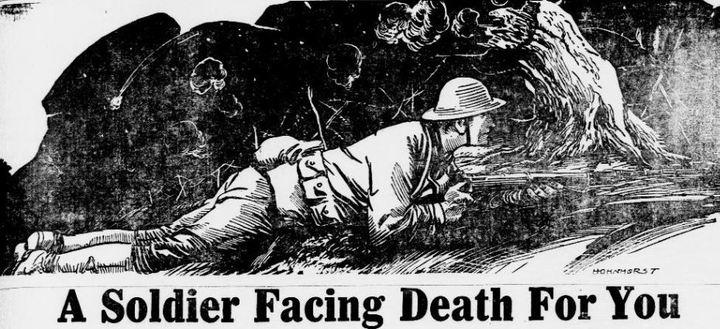

Fourth in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. New Orleans, along with the rest of the United States, was at war. The drafts of 1917 and 1918 would send a total of 71,000 officers and enlisted men from Louisiana to Europe to fight in World War I. On the home front, military installations were built, war bonds were purchased, and the economy boomed to meet new agricultural and industrial demands. In May 1918, Berlin Street in New Orleans was re-named General Pershing as a patriotic gesture.[1] Although many of the dark realities of trench warfare in Europe had yet to touch New Orleaneans, some families had already felt the pain of loss. Grayson Hewitt Brown, only nineteen years old, was stationed at Camp Beauregard near Pineville. A volunteer to the 141st Field Artillery, Brown assisted health care workers during an outbreak of spinal meningitis by carrying a stricken comrade out of the camp. Days later he died of the same disease. His parents buried him in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 along the main aisle with the epitaph, “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends.[2]” But the Great War was only one of two world-wide battles in 1918. The great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 swept across the globe in three waves, the most pronounced of which had only begun to wane by November. Indeed, many of the young men drafted to the military in this year died of influenza before even reaching the trenches. Such was the case for Henry Philip Walter Rathke, not even 26 years old, who died in naval service in New York prior to deploying. He was also buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; he left a widow and a young daughter.[3]

Supply of the flowers had been thinned already by families mourning those died of influenza. By late October, chrysanthemums were advertised at $6 to $9 – $100 to $150 in present-day dollars – and sold at twice the price of roses.[5] The chrysanthemum blight was front page news, and florists noted that customers were purchasing red roses and dahlias, as opposed to the usual “dead white.” In the next year, a third and final wave of influenza would cross the United States, as Louisiana’s enlisted men returned home from war. In 1921, a bronze flagpole was erected in Audubon Park to commemorate New Orleans Great War veterans. Yet the commemoration of those lost to war and influenza took place also in the decoration of graves on All Saints’ Days in years to come.  "The floral world will not be outdone by human beings, it would appear, and is plunged in the midst of one of the most widespread outbreaks of disease in history of local greenhouses... following out the example of human beings as closely as possible," from the Times-Picayune, Oct. 27, 1918. Image Dodd, Mead and Company - New International Encyclopedia (1923), Wikimedia Commons. [1] The Weekly Iberian, May 11, 1918, 4.

[2] “Grayson H. Brown Dies at Beauregard,” Times-Picayune, January 19, 1918, p. 11; “Armory Fund Gets Soldier’s Earnings,” Times-Picayune, August 24, 1918. [3] http://www.rainedin.net/silbern/i11310.htm [4] Natchitoches Enterprise, October 31, 1918, 3; Times Picayune, November 1, 1918, 10; St. Martinsville Weekly Messenger, October 26, 1918, 2. [5] Advertisement of Frank J. Reyes, florist, 525 Canal Street, Times-Picayune, October 20, 1918, 2; “Blight Attacks Chrysanthemum Crop of the City,” Times-Picayune, October 27, 1918, 1. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly