|

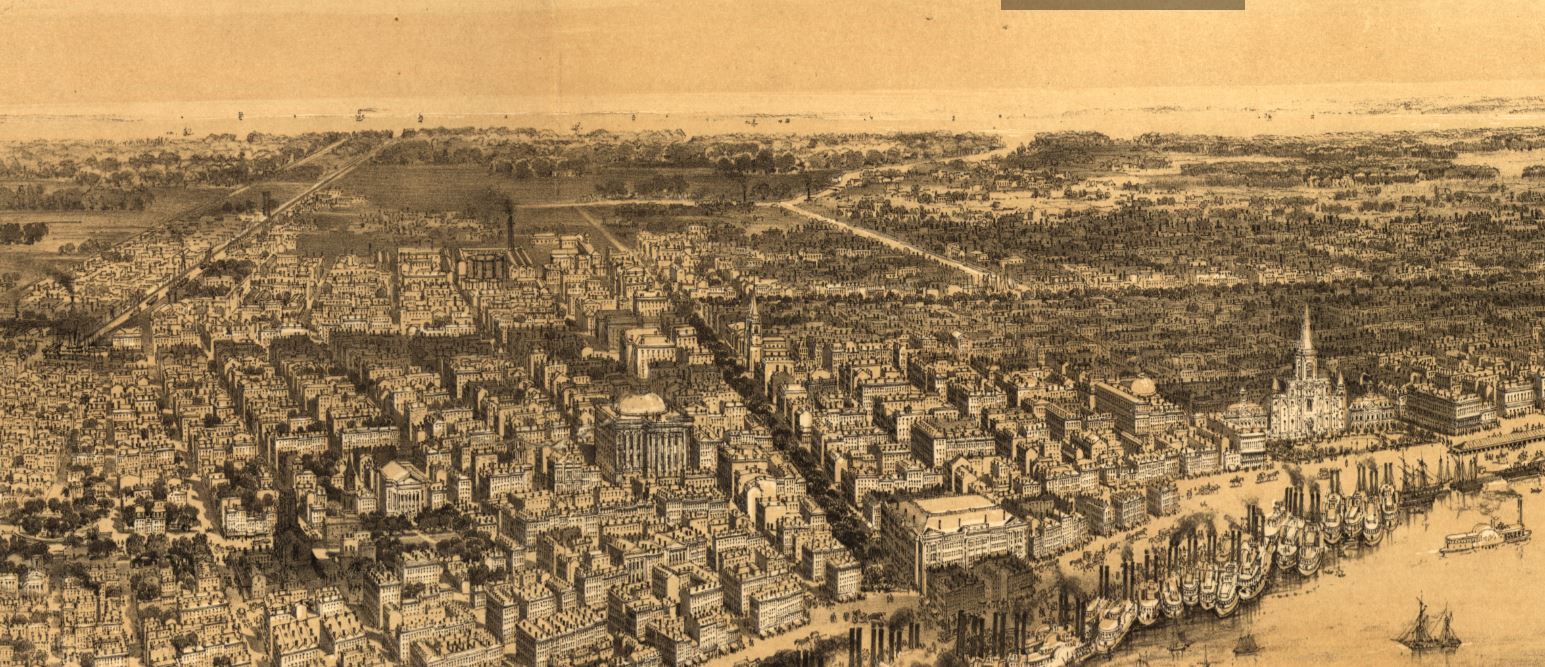

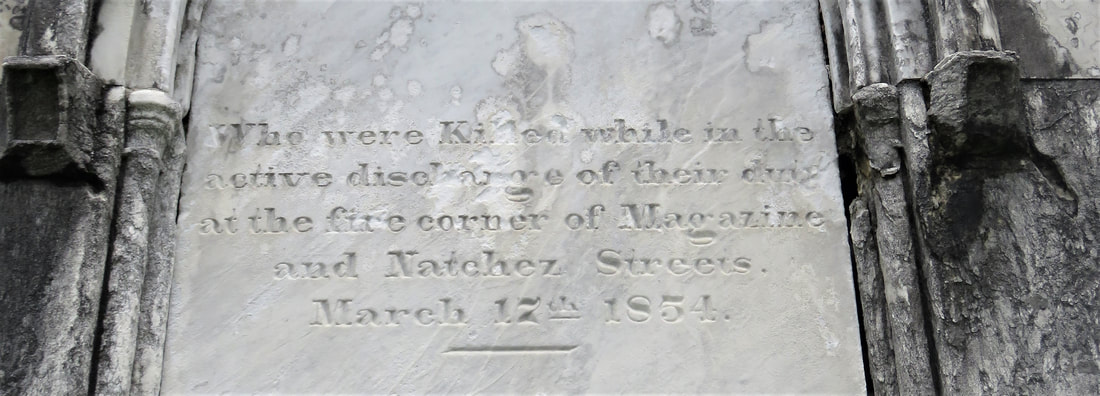

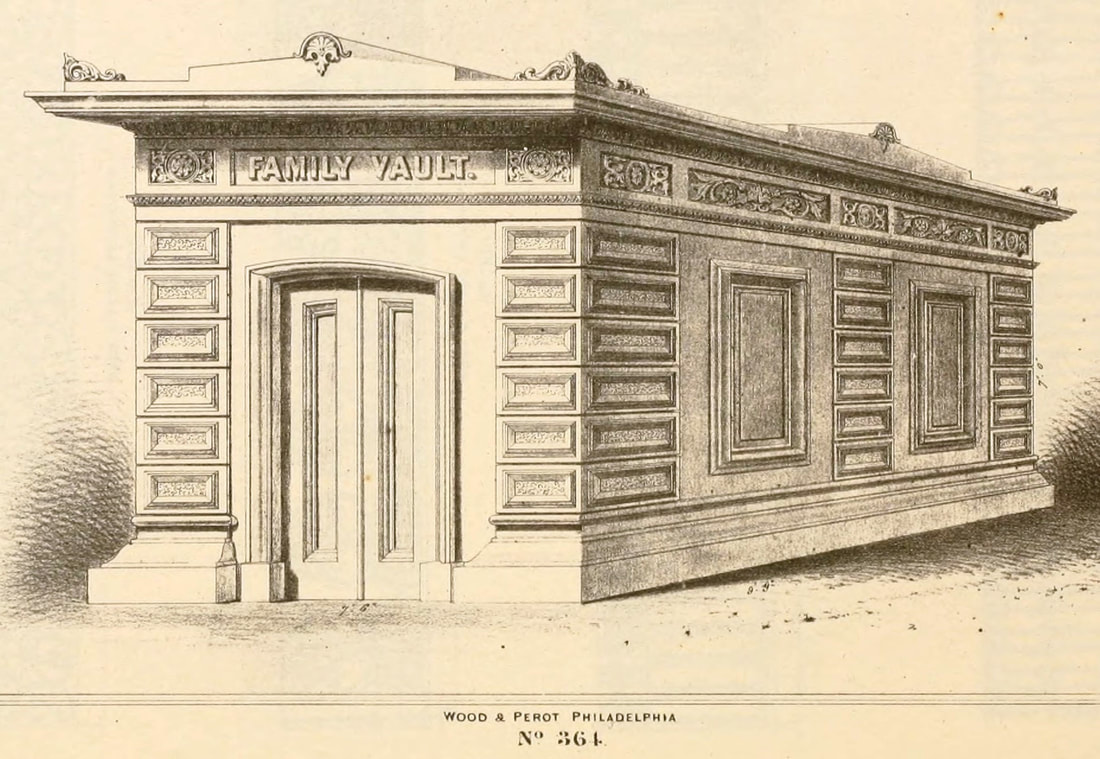

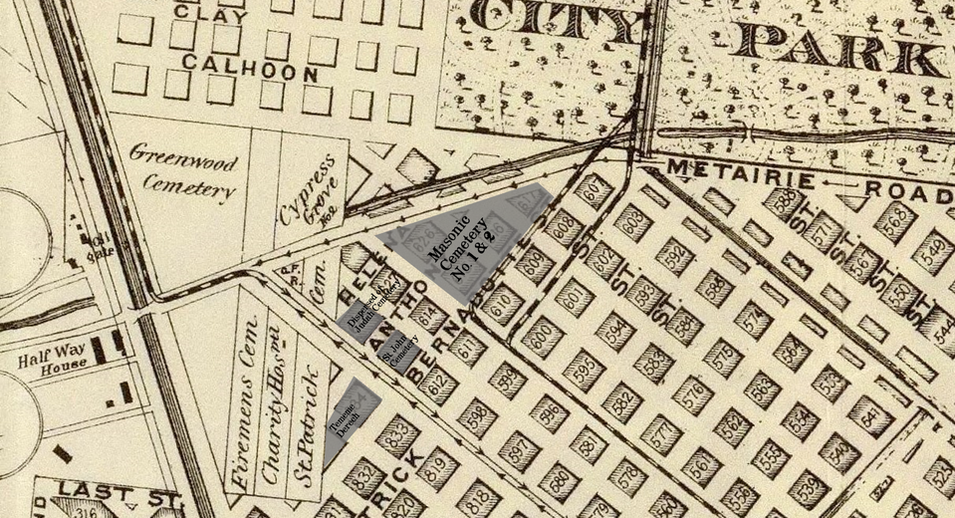

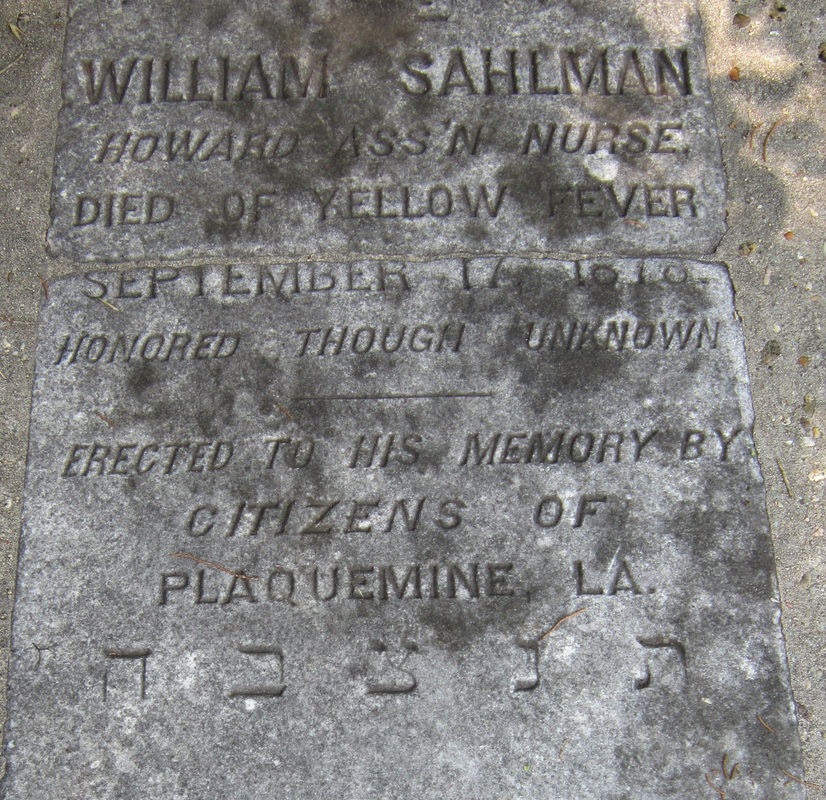

This is Part Three in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here and Part Two here. 1852: Greenwood Cemetery By 1850 the terminus of Canal Street remained mostly undeveloped. On each side of Canal approaching Bayou Metairie were the predominantly belowground Dispersed of Judah, St. Patrick’s, and Charity Hospital Cemeteries, each likely bounded by wooden fences. Improvements like the Halfway House, the Toll House, and the walls of Odd Fellows Rest modestly framed the monumental entryway to Cypress Grove Cemetery. Cypress Grove itself was more than a decade old and flourishing as a garden cemetery full of trees and landscape features – despite a fire in 1848 that destroyed many plantings.[1] The Firemen’s Charitable Association had been quite successful in developing Cypress Grove, so much so that demand for lots overran supply. In 1852, the FCA opened Greenwood Cemetery across Bayou Metairie from both Odd Fellows and Cypress Grove. Its eastern boundary would adjoin Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also known as Charity Hospital No. 2. In some ways, Greenwood Cemetery would be a continuation of Cypress Grove – dedicated to the memorial of fallen firemen and stylistically influenced by Anglo-Protestant aesthetics over those of Creole New Orleaneans. In fact, it’s likely no accident that Greenwood Cemetery shared its name with a famous garden cemetery in New York, founded in 1838. However, Greenwood would not accommodate the landscape features and lofty architecture so well fostered by Cypress Grove. Instead, the new Firemen’s cemetery would be organized in compact, neat rows that mirrored the kind of order seen in contemporary cemeteries like St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 on Esplanade Avenue (est. 1854). A grand dedication ceremony like those seen at Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows Rest would not be held for Greenwood Cemetery. This may have been the result of an almost immediate cholera and yellow fever epidemic following the cemetery’s opening. The 1853 yellow fever epidemic would kill as many as 12,000 people in New Orleans, quickly making Greenwood a vital burial ground. Unlike Cypress Grove or Odd Fellows Rest, Greenwood Cemetery was not enclosed with a masonry wall, but an iron fence. This left the southern boundary of the cemetery visually open to the bayou that meandered in front of it. The grassy space left room for display of more impressive monuments. Decades would pass, however, before the most iconic monuments of Greenwood would appear. The Confederate monument (1873), Firemen’s monument (1887), and Elk’s Lodge tumulus (1911) did not yet rise above the bayou. Instead, one of the first monuments to be erected in Greenwood Cemetery would be that of two martyred firefighters. On March 16, 1854, Daniel Woodruff and William McLeod responded to a fire on Magazine Street as members of Mississippi Fire Company No. 2. In the blaze, a wall fell upon Daniel Woodruff and he was killed in action. Later, William McLeod died of injuries sustained in the fire.[2] Exactly one year after the tragic fire, the FCA laid the cornerstone of the fallen men’s memorial tomb. The Firemen traveled to Greenwood Cemetery in a procession to Metairie Ridge where the cornerstone was laid. In Masonic tradition, the architect of the tomb, Sheppard Reynolds, presented the Grand Master of the FCA with a plumb, square, and level with which to test the cornerstone. After it was pronounced level and plumb, the stone was anointed using vessels of corn, wine, and oil. After an oratory, the procession retreated.[3] The Woodruff-McLeod tomb, similar in style but not size to the Teutonia Lodge tomb, was completed by stonecutter and tomb builder Newton Richards (1805 – 1874), who also constructed the Irad Ferry monument. Each arched loggia-like vault memorializes the life and service of Woodruff and McLeod. Yet only one of the two martyrs are actually buried in this tomb. When the time came to re-inter William McLeod in Greenwood his widow objected. His body remained at Girod Street Cemetery. It is unclear where McLeod may have been re-interred after the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery in 1957.[4] Newton Richards had by 1859 constructed the Irad Ferry monument, the Woodruff-McLeod monument, dozens of other tombs in New Orleans cemeteries, and even the granite pedestal atop which the Andrew Jackson statue is mounted in Jackson Square.[5] A man from New Hampshire who specialized in granite monuments, Richards was especially active in the Anglo-Northern associated cemeteries. In 1859, he would once again shape the budding landscape of Greenwood Cemetery by erecting the memorial of former New Orleans mayor Abidel Daily Crossman in Greenwood Cemetery. A.D. Crossman served four consecutive terms as mayor of New Orleans, weathering the city through natural disasters like Sauve’s Crevasse and the 1853 yellow fever epidemic. He oversaw the re-joining of the city from three separate municipalities into one united city government, and local military response to the Mexican-American War. Crossman was from Massachusetts and had long been a friend of the city’s firefighters – serving as a firefighter himself under Eagle Company No. 7.[6] For Crossman, Richards erected a classical Doric column carved of granite and surmounted with an urn. The granite die and stacked bases atop which the column sits are enclosed with cast iron fencing, the corners of which are each topped with cast iron flaming lamps. The cemeteries at the end of Canal Street were tied not only by geography but, in some cases, mutual origins and culture, specifically that of Northern-born Americans. For this reason, it is no surprise that stonecutters and tomb builders with similar backgrounds tended to concentrate their work in Cypress Grove, Greenwood, and Odd Fellows. In fact, the first sexton of Greenwood Cemetery, Daniel Merritt, also served as sexton in Odd Fellows Rest. Carved tablets signed by Merritt are found in all three cemeteries.[7] Greenwood Cemetery greeted a peculiar new tomb construction in the 1860s – tombs built of brick and mortar but clad in cast-iron panels. This style was not exclusive to Greenwood (Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 had the Karstendiek tomb by 1866, and Cypress Grove famously houses the Leeds cast-iron tomb), but Greenwood gathered the highest concentration of these unique structures. Four of these tombs (Marks, Enberger, Summers, and Hetion) were identical catalog-order tombs from the ironwork firm of Wood, Miltenberger, and Company, which had a branch in New Orleans. The Edwards tomb, also of cast iron, was a custom construction erected in 1861 across the aisle from the Woodruff and McLeod tomb. 1858: Tememe Derech Cemetery Jewish immigration to New Orleans continued through the first half of the nineteenth century. Some Jews emigrated from France, Germany, and the contested territory of Alsace-Lorraine between the two countries. By the 1850s, however, other Jewish people from Eastern Europe began to arrive, fleeing pogroms in their home countries. In 1858, Polish Jews formed the Orthodox congregation of Tememe Derech (“The Right Way”). This congregation was the first Eastern European Jewish congregation to construct a purpose-built synagogue, once on Carondelet Street. Tememe Derech also established its own cemetery across Canal Street from Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, on what is now Botinelli Place.[8] Tememe Derech was not the only Eastern European Jewish congregation in nineteenth century New Orleans. Over time, other congregations formed and merged, and Tememe Derech itself merged with others in 1904 to form Beth Israel Congregation. The new congregation constructed a synagogue on Carondelet Street and designed by Emile Weil. This building is now the New Home Family Worship Center at 1616 Carondelet.[9] As congregations formed and merged among Eastern European Jews in New Orleans, Tememe Derech’s original cemetery would become the burying ground for other congregations, namely Chevra Thilim and later Beth Israel. In 1916, Beth Israel would construct a Metaher house (a traditional chapel for the cleansing of bodies) at the entrance to the Canal Street cemetery. This structure was demolished in the 1960s.[10] The 1860s: A Decade of Change With the addition of Greenwood and Tememe Derech Cemeteries in the 1850s, the confluence of Canal Street, New Basin Canal, and Bayou Metairie had six cemeteries within its bounds. In 1854, New Orleans City Park was founded. Larger than New York’s Central Park and home to the largest concentration of old-growth live oak trees in the world, City Park would add to the character of this area as a place of diversion and rural retreat. A portion of Bayou Metairie running through City Park would eventually be closed off to become a park lagoon. Today, this lagoon is the last remaining vestige of Bayou Metairie. New Orleans as a city was growing in both population and urbanized area. In 1861, the New Orleans City Railroad Company constructed a rail line extending up Canal Street from its foot at the Mississippi River all the way to Bayou Metairie, expanding access and development. The next year, the second fraternal cemetery in the area would arrive when Masonic Cemetery No. 1 and 2 opened at Bienville Street and Bayou Metairie. Despite steady development in the area, it would not escape the humbling effects of natural forces. Metairie Ridge had escaped the flooding of Sauve’s Crevasse in 1849, but would not be so lucky in 1860, when both New Basin and Carondelet Canals overflowed their levies and flooded the area.[11] Another crevasse in 1871 would inundate the cemeteries even more, when the New Basin Canal levy breached at the Halfway House, causing water to flow into the cemeteries.[12] By 1862, additional railroad track was present running alongside Bayou Metairie to the Halfway House. Through the Civil War and into the 1870s, New Orleans’ street grid would encroach toward the cemeteries. Nearby City Park, home to the famous “dueling oaks,” would not be the only venue for such bouts. In 1868, a duel between a Mr. “M” and a Mr. “G” was fought near the Halfway House with swords as the chosen weapon. Although neither man died in the match, neighbors in the vicinity soon afterward requested a police station be placed at the Halfway House – a request that the city council granted.[13] 1867: St. John Cemetery Another cemetery would join the landscape of Canal Street in 1867. Founded by German St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church, St. John Cemetery was the second Protestant cemetery in New Orleans (the first was Episcopal Girod Street Cemetery, founded 1822). St. John Cemetery was owned and managed by the church through the nineteenth century and was religiously restricted. Wrote Leonard Victor Huber, who later co-owned the cemetery with his family, under the church’s ownership “secret societies were not allowed to hold ceremonies in it, and Catholic priests were forbidden by their bishops to officiate services in it.”[14] St. John Cemetery was managed by a sexton who lived on the grounds. The small cemetery at Canal and Bernadotte Streets would develop over time into a typical New Orleans cemetery until the 1920s, when circumstances would transform it into a completely different type of cemetery.[15] The Civil War New Orleans was captured by Union forces in late April 1862, early in the Civil War. The American Civil War was also a time in which the culture and practice of death changed nationwide. Soldiers, accustomed to the concept of a “good death” instead died on battlefields, often buried where they fell. In New Orleans, bodies of both Union and Confederate soldiers were received, transported from elsewhere and buried in places like Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 and Chalmette Cemetery in St. Bernard Parish. After the Civil War, questions of claiming and memorializing the dead dominated conversation. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, also referred to as Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2, received the remains of both Federal and Confederate soldiers. In the 1870s, when the remains of Confederate soldiers were relocated from Chalmette Cemetery to Greenwood Cemetery, remains from other cemeteries including Cypress Grove No. 2 were reinterred in the same place. This effort was headed by the Ladies Benevolent Association of New Orleans, who erected the Greenwood Confederate monument atop this mass grave of 600 soldiers in 1873. The “Old Soldier’s Home,” established in 1866 by the State of Louisiana for Confederate veterans, also had a society tomb in Greenwood Cemetery by 1868. Remains of Union soldiers were also removed from Cypress Grove No. 2, as well. In the 1920s, as the old potter’s field was beginning to be redeveloped as a road and dumping ground, Federal soldiers were disinterred from Cypress Grove No. 2 and relocated to Chalmette National Cemetery. On All Saints’ Day, November 1, 1868, New Orleaneans observed the yearly tradition of decorating and visiting graves. The New Orleans Republican offered a glimpse of the Canal Street cemeteries on this day, noting the “noble monuments” of Cypress Grove, and nodding to the society tombs of the Deutscher Louisiana Draymen Verein (now mostly demolished), and the New Orleans Typographical Union in Greenwood Cemetery. Odd Fellows was described as well, “with its specious avenues bordered with trees and lined with the tombs of good and charitable men, is one of the most attractive of the homes of the dead.”[16] The rural cemeteries at Canal and City Park Avenue had matured into landscapes of marble, granite, limewash, and green landscaping. Each cemetery enclosed by masonry walls, picket fences, or painted ironwork, they framed canal and bayou as carriages and barges passed through. As much as the landscape had changed over three decades since the New Basin Canal opened, it was about to transform even further with the founding of an entirely new cemetery, the likes of which the city of New Orleans had yet to see. [1] Thomas O’Conner, editor, History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: Thomas O’Conner, 1891), 75.

[2] O’Conner, 84-85. [3] “Woodruff and McLeod Monument,” Daily Picayune, March 18, 1855. [4] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 39. [5] “Inauguration of the Equestrian Statue of Andrew Jackson,” Daily Picayune, February 9, 1856, 2. [6] O’Connor, 127. [7] “Firemen’s Charitable Association, Cypress Grove and Greenwood Cemeteries,” Daily Picayune, June 17, 1855; “Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, January 21, 1862. [8] Catherine C. Kahn and Irwin Lachoff, Images of America: The Jewish Community of New Orleans (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 24; The Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, “History of Orthodox Congregations in New Orleans.” http://www.msje.org/history/archive/la/HistoryofOrthodoxCongregations.htm [Accessed September 10, 2017] [9] Barry Stiefel and Emily Ford, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012), 47, 77-80. [10] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 22-23. [11] “Overflow of Canals,” Daily Crescent, October 4, 1860, 1. [12] “The Last Great Flood: Rear of the City Submerged,” New Orleans Republican, June 4, 1871, 1. [13] “Dueling,” New Orleans Republican, May 30, 1868, 3; “To the Common Council of the City of New Orleans,” New Orleans Republican, May 31, 1868. [14] Huber, et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol III: The Cemeteries, 47-48. [15] Ibid. [16] “All Saints Day,” New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1868, 1.

0 Comments

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Throughout the course of the nineteenth century, the New Orleans Jewish experience varied among individuals and families, from great successes to great defeats. For some, it was something one was born into: by mid-century, a number of families had developed deep roots in New Orleans commerce and culture. For men like Judah P. Benjamin and other merchants, lawyers, and factors, New Orleans was a place of opportunity among aristocrats and politicians. For others, however, New Orleans was a refuge, only slightly improved from the poverty and exclusion of the homeland from which they had fled. Among the Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who immigrated to New Orleans between 1840 and 1880, many found their new home to be wracked by destitution, disease, and an uncertain future. These immigrants formed their own communities, establishing a familiar cultural norm to ease their transition in the New World.[1] Two New Orleans stonecutters exemplify this wide spectrum of experience. Edwin I. Kursheedt, part of an influential Jewish family, was successful not only professionally but personally. Committed to charity and military service, he inherited his business from his father and carried it into the twentieth century. Alternatively, the carved signature of H. Lowenstein is nearly all that remains of this stonecutter’s legacy. It is likely that his time in New Orleans was brief, cut short by disease, war, or the search for better opportunities.

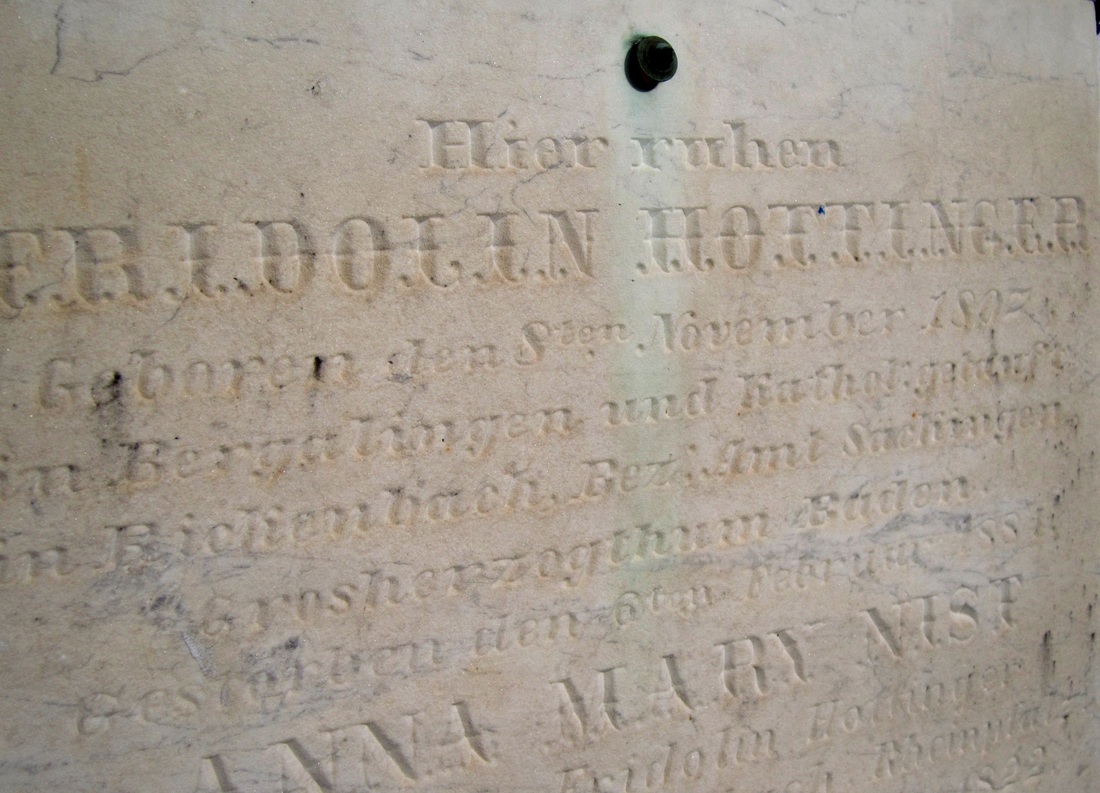

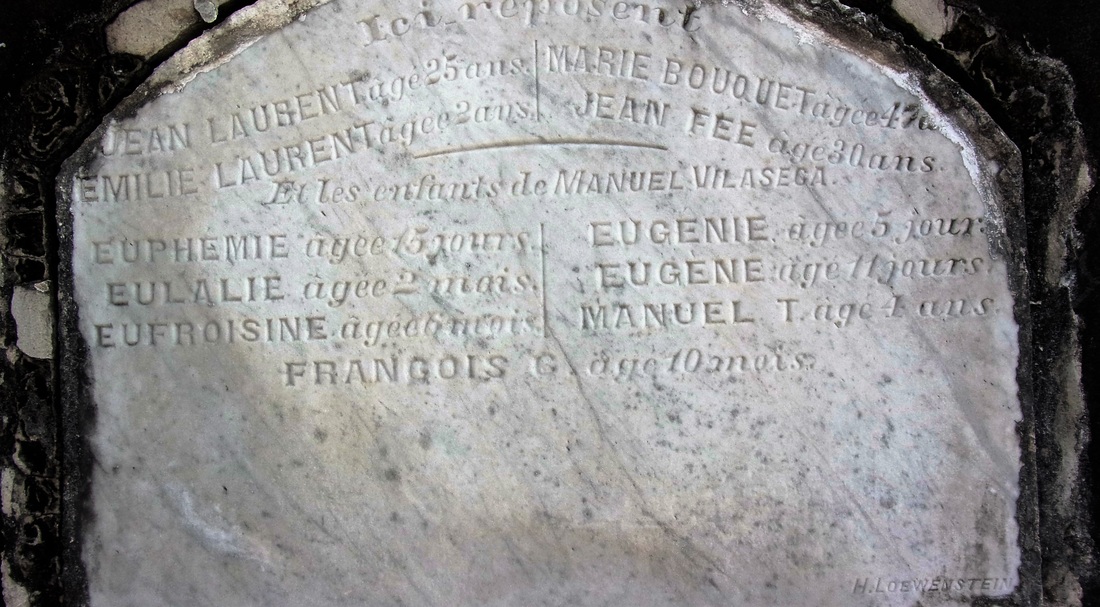

The address of H. Lowenstein’s business is recorded in directories and on his signed tablets as 195 and 197 Washington Avenue, which corresponds to the historic marble yard and shop located across Washington Avenue from Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. During the years Lowenstein held business there, other stonecutters and sextons advertised at the address, namely James Hagan and Philip Harty. Lowenstein also advertised himself as an undertaker at this address. Lowenstein’s carving style bears a resemblance to that of other contemporary German stonecutters, namely the Anthony Barret and his sons Charles and Frederick. These artisans carved in the German Fraktur style, or black-letter, and employed similar imagery of oak and laurel wreaths that are not found among the work of non-German craftsmen in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. These scant traces of Lowenstein in New Orleans indicate that he was likely a German-Jewish immigrant who served the community of the Fourth District, once part of the suburb of Lafayette. A number of German newspapers, including the Deutsche Zeitung and the Louisiana Straatszeitung, may have been the venue for his advertising. Considering he frequently carved closure tablets in German, it is likely that he aided more established craftsmen like Hagan and Harty with their business in the German immigrant community. Yet, after 1869, documentation of H. Lowenstein evaporates completely, suggesting that, like many other Jewish immigrants in the South, he may have moved elsewhere, or possibly died young in New Orleans.

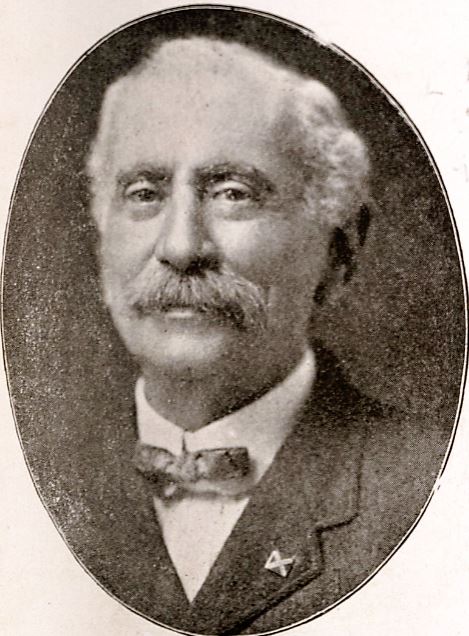

The business of Kursheedt & Bienvenu was among the most successful and prominent merchants of not only cemetery stonework and tombs but also hardware, commercial stonework, mantels, grates, and other items. By the 1880s, they owned not only a large show room on Camp Street but also a marble yard next door, at which at least thirty men were employed.

Much of Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s signed work can be found in Jewish cemeteries in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Alexandria, and Plaquemine, among other Louisiana towns. Within Jewish cemeteries, this work consists of headstones, as Jewish tradition prohibits above-ground burial. Yet Kursheedt & Bienvenu served clients of all religions and traditions. Among their most visible commissioned works is the Sercy tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Marked by a stone sarcophagus and located near the Washington Avenue cemetery gate, it is most notable for its epitaph: “Died of Yellow Fever,” a relic of the 1878 epidemic. J.G. Bienvenu left the business after 1888, and Edwin Kursheedt operated Kursheedt’s Marble Works until 1901.[8] Throughout these years, he served on various boards for Jewish Charities, including Touro Infirmary, the Hebrew Benevolent Association, and the Jewish Widows and Orphans Home.[9] He died in on February 21, 1906, at the age of sixty-seven, a veteran, merchant, benefactor, husband and father. He is buried in Dispersed of Judah Cemetery on Canal Street. It is unclear where or when H. Lowenstein died. The only tenuous hint points to an obituary published in the New Orleans Daily Picayune November 3, 1896, reporting the death of Henry Lowenstein, who died at the age of fifty-six in Cincinnati, Ohio. That a New Orleans newspaper reported his death suggests he once lived in the city, and may have been a young stonecarver on Washington Street in 1861, but no definitive documentation can support this possibility.[10] So these two artisans whose work is marked in New Orleans cemeteries died as they lived: one documented and memorialized, one lost in historic thin air, as were many immigrants who came and went from the Crescent City in the nineteenth century. [1] Bobbie Malone, “New Orleans Uptown Jewish Immigrants: The Community of Congregation Gates of Prayer,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 32, No. 3, Summer 1991, 239-287; Ellen C. Merrill, Germans of Louisiana (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2005), 225, 236.

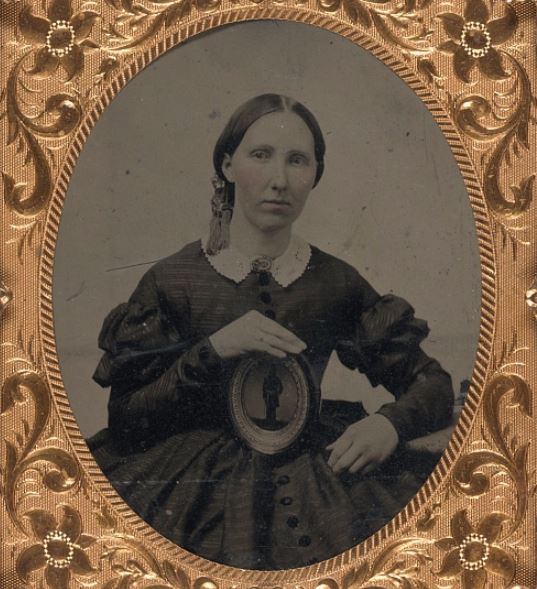

[2] The signature “Löwenstein” can be found on the Fridolin Hottinger tomb, Quadrant 2, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1861 (New Orleans: Charles Gardner, 1861), 282; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1866 (New Orleans: True Delta Book and Job Office, 1866), 279; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1869 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1868), 399. [3] Bertram Wallace Korn, The Early Jews of New Orleans (American Jewish Historical Society: 1969), 247-249; “Mr. Israel Baer Kursheedt,” The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, Vol. X, No. 3, June 1852, 1. [4] Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 111-116. [5] Andrew Morrison, The industries of New Orleans: her rank, resources, advantages, trade, commerce and manufactures, conditions of the past, present and future, representative industrial institutions, etc. (New Orleans: J.M. Elstner & Co., 1885), 144. [6] Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 21, 1880, 5; “The Other Side: The Report Adopted by the State-House Commission Respecting the Work Done,” Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 28, 1880. [7] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1887 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishers, 1887), 513. [8] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1889 (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1889), 532; Soards’ New Orleans City Directory, for 1901, Vol XXVIII (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1901), 501. [9] W.E. Myers, The Israelites of Louisiana: Their Religious, Civic, Charitable and Patriotic Life (New Orleans: W.E. Myers, 1904), 103. [10] Daily Picayune, November 3, 1896, 4. See also, Emily Ford and Barry Stiefel, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (History Press, 2012). The second in a five-part series of All Saints' Day celebrations in New Orleans history. Need we say whose graves they were? Need we say whose fair hands placed those mementoes there, or whose kind hearts prompted the deed? On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, ending the Civil War. In New Orleans, infrastructure and economy lay in ruin. By November, the observance of All Saints’ Day was fundamentally changed from antebellum celebrations – in fact, the way all Americans interacted with death had changed forever. In general, nineteenth century Western culture was marked by an intimacy with death that would be incomprehensible to most modern-day people. Understanding that death could be swift and sudden, each person hoped only for a “good death” – one in which last words could be uttered, surrounded by loved ones. This ideal was sought even among soldiers, who kept letters in their pockets in case of their death, or who wrote such letters for dying friends. Yet the horrific realities of war – and the bad death that was its companion – were unavoidable. Advances in technology led to extensive photographs of Civil War battlefields, exposing civilians to the carnage of the conflict, and “stripping away much of the Victorian-era romance around warfare.”

The destruction of the Southern economy in 1865 and 1866 is unlike anything any Americans ever experienced at any other time, at least on our home soil. The writers from Northern newspapers and magazines who went South after the war end up observing open coffins laying all over the place at cemeteries. They end up seeing old men and former slaves going around collecting bones because they could get a dollar for so many pounds of bones off battlefields. Those are the bones of men who died -- without a name, a place, they were never sent back to their families. This is what people would see if they went to those battlefields in 1865 and 1866 -- and for that matter for many years afterward. Most of the Civil War cemetery monuments we know today – the Confederate Army of the Tennessee and Army of Northern Virginia monuments, the Confederate monument at Greenwood Cemetery, the Grand Army of the Republic monument at Chalmette National Cemetery – were not erected until the 1870s and 1880s. In the years between Appomattox and the first official Memorial Day in 1868, efforts by Clara Barton and others to identify and re-locate fallen soldiers on both sides of the conflict resulted in the disinterment and reburial of thousands in New Orleans alone. However, this process would take years. On November 1, 1865, a great many of those who would come home were not yet located or reburied. Documents state that it was a beautiful Wednesday of extremely pleasant weather. Among the notable architecture newspapers chose to highlight in this year were the tomb of the New Lusitanos Benevolent Association and the tomb of W.W.S. Bliss, both located in now-demolished Girod Street Cemetery. They also noted the then-burial site of Albert Sidney Johnston in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. General Johnston was later re-interred in Texas: Several soldiers in tattered gray stood around. “You served under him,” we remarked to one, as we looked at him. Tears started in his eyes as he merely said, “yes,” and pulled a twig from a cedar circlet, hanging on the grave, and handed it to us. Other articles point out the noticeable presence of many more male attendees to ceremonies than in years past. Yet the focus of the holiday in 1865 seemed to be on the women – mothers and spouses who mourned lost soldiers. The Lusitanos tomb is described as attended by wailing women. In another account, women tend to the simple wooden monuments that temporarily marked their loved ones’ resting places: …we came upon a number of graves, very plain and unpretending, with but a wooden foot and head board… Not one was left undecorated – not a single one without a flower, a bouquet, or a wreath to mark that some kind, gentle, amiable feminine heart had stood there to tender a memento to departed valor. Need we say whose graves they were? Need we say whose fair hands placed those mementoes there, or whose kind hearts prompted the deed? They were the same heroic women of our city who, with noiseless step and sad, earnest eye, have treaded the avenues of the hospitals during the last four years, in search of the wounded and dying soldiers… Ten of them had assembled under a lofty oak… and spent almost the entire day in preparing wreaths and decorating those humble graves. Sources:

PBS American Experience: Death and the Civil War “The City,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1862, 1. Army of Northern Virginia tomb erected 1881; Army of the Tennessee tumulus erected 1887; Confederate Monument at Greenwood Cemetery, remains relocated 1868, monument erected 1872; Grand Army of the Republic monument completed 1883. “The City,” Daily Picayune, November 1, 1865, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1865, 1. Daily Picayune, November 5, 1865, 1. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly