|

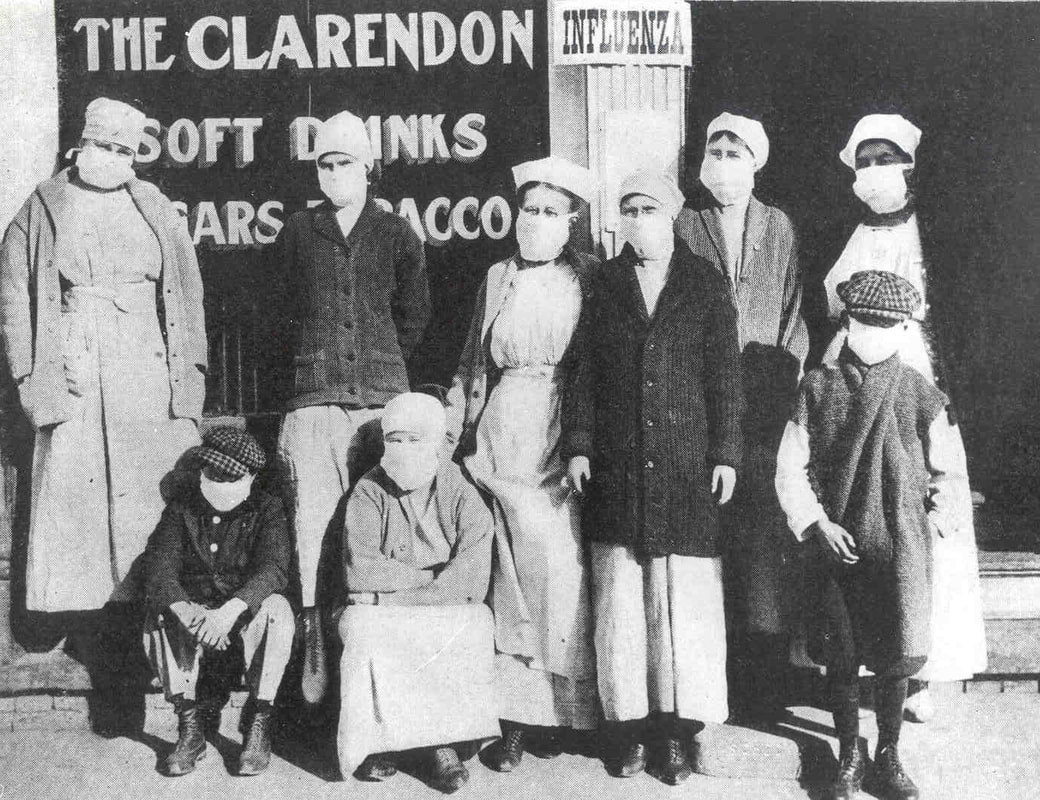

How New Orleans weathered one of the greatest plagues in history. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a worldwide emergency like that which took place in 1918. Modern-day fiction and sci-fi writers have materialized similar fears – there is no shortage of post-pandemic fiction. For example, the HBO series The Leftovers posits a world in which two percent of the world’s population has vanished, the Max Brooks novel World War Z injects zombies into a frighteningly realistic image of how civilization would handle pandemic catastrophe. The list goes on. But we so often forget that something like this did happen. In 1918, a strain of pandemic influenza swept the globe three times, infecting millions and killing five percent of the world’s population. Medical science today cannot pin down exactly where it began. One prominent theory states that H1N1 influenza began with swine farms in Haskell County, Kansas in late January 1918.[1] Like other incidents of mutated influenza virus “jumping” from livestock to humans, it could have fizzled out in the local population. Yet nationwide mobilization in response to the United States’ entry into World War I meant that military camps were ubiquitous and population movement intensified. Influenza was transported to Camp Funston, Kansas, where it spread to other camps, other towns. The first wave of influenza traveled from the United States to Brest, France, in April 1918. Within the next month, it spread to Spain. Spain, neutral during World War I, was less likely to censor press reports of the disease. Hence, although the U.S., Britain, and France saw just as many cases of influenza, such incidents were not reported. The uneven press coverage created the appearance of the disease originating in Spain, giving it the incorrect moniker “Spanish Influenza.[2]” Influenza was documented in China and India by May 1918. The spring wave, however, was comparatively mild. The second wave of Fall 1918 would be devastating. As the summer of 1918 wore on and Allied victories in Europe continued, state and federal medical officials assumed disaster had been averted.

Attempts to quarantine the sick and curb the spread of influenza were often thwarted by the pressures of total war. In one especially salient instance, insistence from upper-crust social circles in Philadelphia caused medical leaders to allow a War Bonds parade to take place, despite the mounting evidence of an influenza epidemic. New cases of the illness soared in the days after this large public gathering. In metropolitan areas, the flu jumped from military to civilian populations, and then spread.

One hundred years ago this month, influenza arrived in New Orleans.

5 Comments

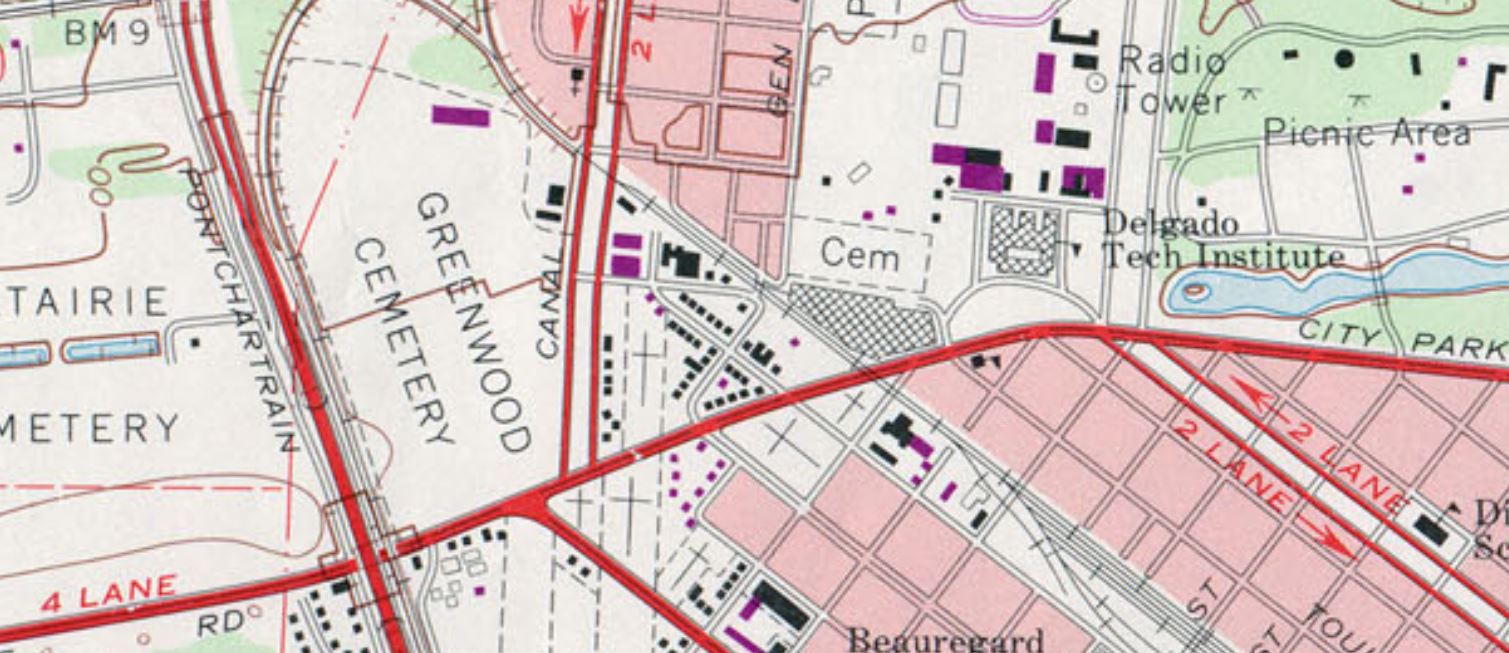

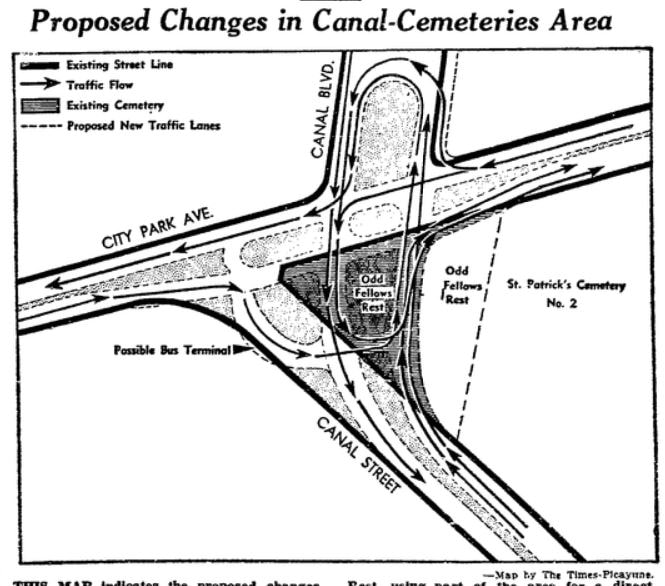

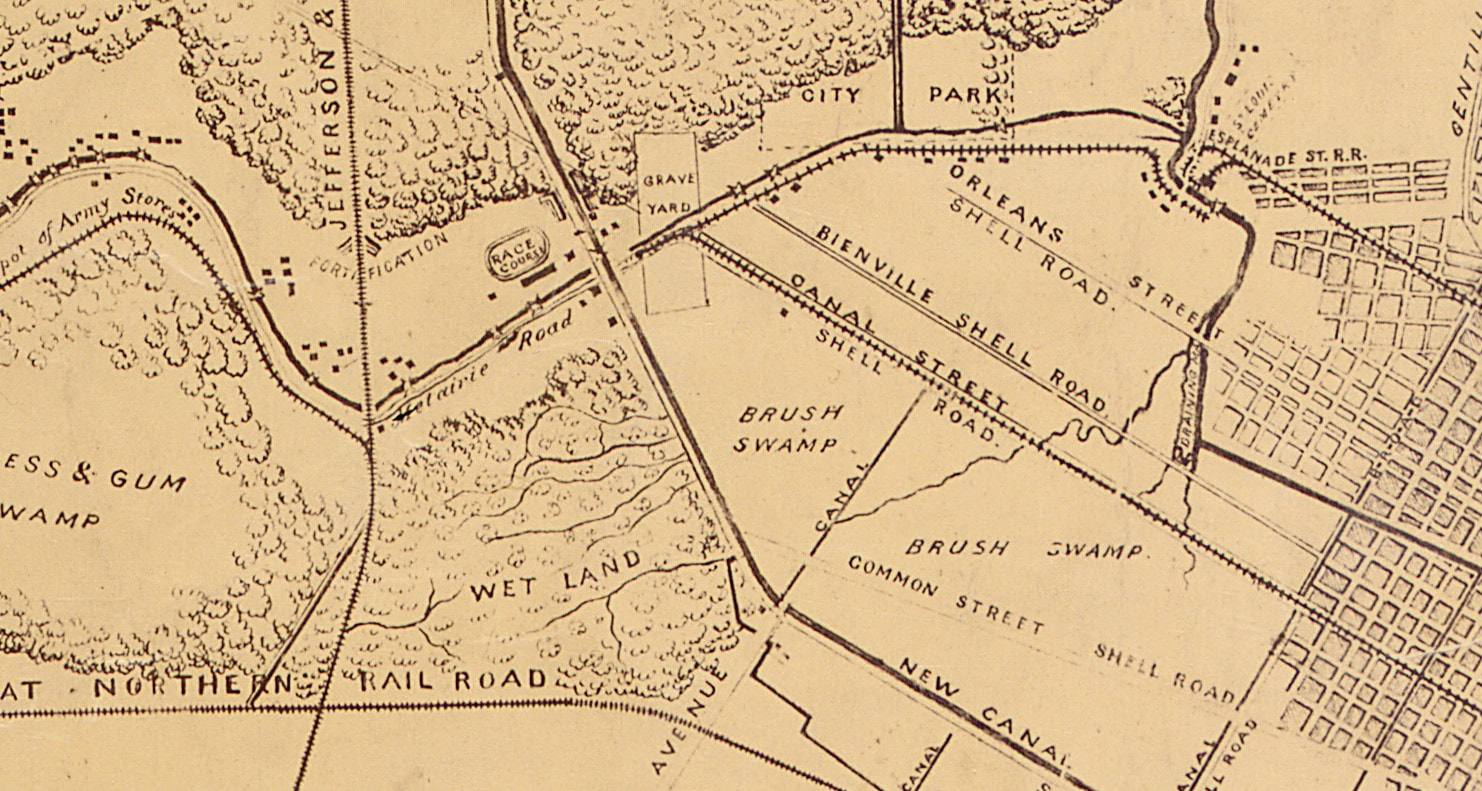

This is the fifth and final part in a five-part series on the historic landscape of City Park Avenue and Canal Street, and its associated cemeteries. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. To start at the beginning of this series, find Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here, and Part Four here. By the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue had undergone a century of extraordinary change. Where once Bayou Metairie meandered westward past acacia trees and a pastoral ridge, now City Park Avenue coasted across the New Basin Canal to become Metairie Road, past the grand monuments of Metairie Cemetery, and into Old Metairie. Where once the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove stood tall over an undeveloped landscape, now cars rumbled past the monuments and walls of Greenwood Cemetery and Odd Fellows Rest. Jazz blared from the Halfway House beside the New Basin Canal through the 1920s, until the House was converted into an ice cream parlor in 1930.[1] Bayou Metairie had slowly been filled in to accommodate City Park Avenue. To the east, Delgado Central Trades School (now Delgado Community College) was opened in 1921. Beside Delgado, Holt Cemetery remained the municipal potter’s field for New Orleans, but in 1940 the cemetery gained a new neighbor – the Higgins Boat Plant. PTs, Higgins, and the Cemetery Andrew Higgins (1886-1952) is known today in New Orleans as the man who brought the shallow-bottom PT and “landing craft, vehicles, personnel” or “LCVP” boats to the Allied effort in World War II. LCVP boats were used extensively in the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1945, leading then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower to say in 1964 that Higgins had “won the war for us.” Before World War II, Higgins had gotten his start designing shallow-bottom boats that performed well in the Louisiana bayous and other waterways beset by submerged obstacles. But by the late 1930s, Higgins produced new designs that not only could achieve amphibious landings in shallow waters, but were also equipped with ramps to allow swift disembarkation upon landing. These qualities made Higgins Boats imperative to the war effort. In 1940, Higgins Industries constructed a $1.5 million boat-building facility in the least expected of places: far from water, along City Park Avenue, and beside Holt Cemetery. Ever known for his enterprising spirit, Higgins’ City Park plant became the “world’s largest boat manufacturing plant housed under one roof.”[1] The plant took advantage of the Southern Railway line that cut northwesterly across City Park Avenue, beside Masonic Cemetery No. 2. Boats would be manufactured at the City Park plant, which employed thousands of people, and shipped to Lake Pontchartrain for testing. The booming wartime production of the plant left the operation bursting at the seams. Said historian Jerry Strahan of Higgins’ need to expand: “The back of the shipyard was adjacent to Holt Cemetery. Higgins decided to enlarge the plant ‘knowingly and willingly’ by preempting an unused portion of the cemetery grounds. The plant was increased until 40 percent of the new facility was constructed on property to which Higgins held no title, a problem that was unresolved as late as 1947.”[2] Photos of the plant and adjoining Holt Cemetery can be found here under photographs numbered 14 and 21. As early as November 1945, the loss of massive wartime governmental contracts hit the Higgins plant hard. The property was put up for sale.[3] The building at 501 City Park Avenue would have myriad uses over the next thirty-five years – it was a Piggly Wiggly grocery store in 1948, offices for Georgia Pacific Corporation in 1959, and part of the building was used as an art warehouse in 1964.[4] From the 1960s through the 1970s, a van and storage company conducted business in the old plant. In 1972, the building was demolished - its walls, beams, floors, and other items sold for salvage.[5] Finally, in 1982, Delgado Community College opened the Arthur J. O’Keefe Administration Building at 501 City Park Avenue.[6] The architecturally intriguing building remains in the same capacity to this day. In 1964, Holt Cemetery would cease to serve as New Orleans’ potter’s field. The city of New Orleans, under coroner Frank Minyard instead leased a lot from Resthaven Cemetery in New Orleans East for this purpose. This section of Resthaven continues to serve as New Orleans’ indigent burial ground. The American Way of Death After the close of World War II, industries which had boomed forward industrially and technologically looked inward for domestic uses of their innovations. Higgins Industries attempted to this very thing: selling Higgins-designed watercraft for private uses. While to contemporary readers it may seem strange, the same phenomenon took place in the funeral and cemetery industries. Moreover, the clientele of these industries had changed: they were more prosperous, more mobile, and had different values. For 1950s Americans, death was to be confronted with more discretion, privacy, and modernity than had been the case for previous generations. The cultural boom of the 1950s held an inherent disdain for the old-fashioned. This trend is often best exemplified in the scorn held for Victorian architecture during this period. Modern Americans sought urban renewal to wipe away old landscapes. In New Orleans, such sentiments manifested in the rapid construction of community mausoleums, establishment of “memorial park” style cemeteries like Garden of Memories, and the destruction of Girod Street Cemetery. Girod Street Cemetery was established in 1822 at the foot of Girod Street near Liberty Street. By the mid-1950s, the cemetery was bounded by the New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, part of a neighborhood seen as old, blighted, and an obstruction to progress. After repeated attempts by the cemetery’s owner, Christ Church Cathedral, to resurrect the cemetery both architecturally and functionally, it was expropriated by eminent domain to the federal government and the City of New Orleans. The cemetery was demolished in 1957. Girod Street Cemetery was located far from the Canal Street cemeteries, but it held certain cultural and architectural ties to other Protestant-dominated cemeteries like Cypress Grove and St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery. As the process of demolition began, the Huber family which had assumed ownership of St. John’s Cemetery in the 1920s, jockeyed for the contract to relocate the Girod Street remains. This competition involved multiple cemetery craftsmen-turned-cemetery owners and would not be the last time a cemetery operator competed for business with his peers. At the same time Girod Street Cemetery was being demolished, cemeteries at Canal Street and City Park Avenue were modernizing. The first inklings of cemetery stoneworkers turning to cemetery operation began in the 1910s and 1920s. For example, in 1910, stonecutter Albert Stewart assumed ownership of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street, acquiring it from the Suarez brothers. The Huber family had gained ownership of St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery in the 1920s – and by the 1930s, began construction on Hope Mausoleum, the first community mausoleum in New Orleans. Community mausoleums had gained some traction in the United States beginning in the 1890s and increasingly so in by the time of the Great Depression. In this era, the idea of a large, single-structure facility for burial appealed to cultural ideals of mutual benevolence (indeed, many belonged to fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows) and frugality. In New Orleans, these cultural desires were often met instead with society tombs – large, multi-vault structures within larger cemeteries. Society tombs were New Orleans’ version of community mausoleums, which reflected a more northern aesthetic. It is, then, not surprising that the Huber family gained ownership of German Lutheran St. John’s Cemetery and erected Hope Mausoleum around the historic burial ground. The development almost appears as an extension of St. John’s, Girod, and Cypress Grove Cemetery’s tendency to reflect non-Francophile aesthetics. In the early 1930s, Hope Mausoleum opened, a modestly Art Deco edifice encased in polished marble and touting itself as, “The Modern Way of Burial.”[8] The postwar boom of the 1950s saw a second heyday for community mausoleums, but these mausoleums suited newer cultural norms. The era valued opulence and modernity, sleek, state-of-the-art materials and a dearth of filigree and detail. The funeral and cemetery industries, rising into a new period of lobbying professional organizations, consolidated costs, and property accumulation, responded in kind. Indeed, author Jessica Mitford in her 1963 indictment of the industry, The American Way of Death, compared the contemporary funeral industry to the car industry of the same age: overloaded with space-age fins and baubles.[9] Thus, the new community mausoleum was meant to be an expression of modernity and opulence, and a doing-away with the stodgy funereal rituals and trappings of the past. Into this new market rose the children of Albert Stewart – Frank Sr. and Charles Stewart. Under their business, Acme Marble and Granite Company, the Stewarts purchased land adjoining the north boundary of Metairie Cemetery and set forth to construct a community mausoleum for the age. Completed in 1958, Lake Lawn Mausoleum would be the “the ultimate in modern burial,” with “paneling of rich mahoganies, carpeted floors, custom-built furniture, and rare plants and flowers.”[1] Lake Lawn would be the anti-Girod Street Cemetery. Historic photos suggest that Lake Lawn advertised within the walls of Girod Street, declaring that burials removed from the old Protestant cemetery could be moved to a thoroughly modern location. In fact, the engineer of Girod Street Cemetery’s demolition, Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, did just that. The contents of the Story family mausoleum, relatives of Mayor Morrison, were moved to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum in May of 1956. In the end, though, Hope Mausoleum would gain the contract to re-inter the white burials from Girod Street Cemetery. In accordance with contemporary segregation laws (even in death) Providence Memorial Park in Metairie would receive the African American burials from Girod Street. The torchbearer of urban renewal, Mayor Chep Morrison, would himself in death become part of the struggle between rising cemetery entrepreneurs, and the clash of new and old New Orleans cemetery culture. Shortly before his death in 1957, entrepreneurial monument man Albert Weiblen, who by this time had expanded his business to owning entire quarries in Georgia, purchased the entirety of Metairie Cemetery. His widow Norma maintained this enterprise after Albert’s passing, and when Mayor Chep Morrison perished in a tragic airplane accident in 1964, a standoff ensued between old Metairie Cemetery and modern, neighboring, Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Mayor Morrison had, as mentioned previously, moved his family’s remains from Girod Street Cemetery to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Yet while the new mausoleum was modern, Metairie Cemetery had been the lauded resting place of New Orleans mayors, governors, and Mardi Gras kings (nine, eleven, and more than fifty, respectively[1]). Metairie’s position in New Orleans culture was to be the hallowed resting place of power in all its forms. Presumably to preserve this reputation, Norma Weiblen called Morrison executor William H. Lindsay, Sr. on May 24, 1964, offering the Morrison family very steep discounts on a new tomb in Metairie Cemetery if they would consider moving Mayor Morrison’s burial there from Lake Lawn Park. She added that Lake Lawn Park was a “stinkpot,” and that she “knew [Metairie Cemetery] was where [Morrison] belonged.”[2] Years later, the matter would result in a lawsuit. Morrison was buried in Metairie Cemetery and, in 1969, Stewart Enteprises purchased Metairie Cemetery, renaming the joined properties “Lake Lawn-Metairie Cemetery.” The modernization of historic cemeteries at the end of Canal Street was fueled by the spirit of an era – and a struggle for space. By the 1950s, many of the cemeteries in the area were more than a century old. Furthermore, the city of New Orleans and the suburb of Metairie had grown tightly around them, leaving no room to expand. Community mausoleums were a practical way to capitalize on sellable space. Metairie Cemetery had made such a venture – filling in one of the cemetery’s lagoons to construct Metairie Mausoleum in 1958. In 1964, the various parish-owned Catholic cemeteries in New Orleans would be consolidated under the new New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. Ten years later, the Calvary at the rear of St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1 would be demolished to construct Calvary Mausoleum. In 1969, the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association would open Greenwood Mausoleum. The Jewish cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would also reorganize ownership. In the late 1950s, the Hebrew Burial Association would form to assume ownership of Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. With religious restrictions against above-ground burial, the cemetery instead appears to have expanded toward Bernadotte Street in this time, where today a section of modern, 1950s granite monuments stands. In 1973, conservative congregation Chevra Thilim established Chevra Thilim Memorial Park in a small triangle of land bounded by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, and Iberville Street. In 1999, Chevra Thilim merged with another congregation to form Shir Chadosh congregation, who retains ownership of the memorial park-style cemetery. Canals, Streetcars, and Automobiles Within cemetery walls, local stonecutters became sales agents and marble increasingly gave way to increased use of granite. No longer the city’s potter’s field, Holt Cemetery became a burial ground for the families of those already interred therein. Outside the cemeteries of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, water and soil gave way to concrete and pylons The New Basin Canal, in service since 1838 and arguably the heart of the cemeteries landscape, was by the 1950s no longer fit for industrial use. As with Bayou Metairie before, the canal was filled in and repurposed for automobile use. In 1958, a new overpass was constructed for City Park Avenue traffic to traverse over the canal, but its use would be short lived. By 1962, sections of the canal nearest to Lake Pontchartrain were filled in and became West End Boulevard. At the end of the wide boulevard’s neutral ground, a civil defense bunker was constructed as a station of command for government in the event of nuclear war. The bunker has been abandoned since the late 1990s, but remains present on West End Boulevard near Robert E. Lee Boulevard. Finally, in 1968, plans that had begun in the 1950s with Mayor Morrison came to fruition and a superhighway was constructed to connect Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Pontchartrain Expressway, part of Interstate 10, was constructed above the filled-in New Basin Canal – replacing high levies and deep water with tall pylons and dipping underpasses. Increased automobile traffic was met with increased automobile infrastructure, but one seemed to continually outpace the other. The roadways as they were in 1968 were complex and disconnected: Canal Boulevard met City Park Avenue, which met Canal Street in a dog-leg which already vexed motorists. The triangular lot of Odd Fellows Rest formed this dog-leg, and in the 1960s, civic eyes turned to eliminate the obstacle. The (sort-of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest As early as 1948, New Orleans’ City Planning Commission recognized the “dog-leg” problem.[13] As automobile drivers increasingly used Canal Boulevard and Canal Street as a commuter route to and from the city, the multiple turns needed to achieve this route caused traffic congestion. While the commission desired nothing more than to connect the two streets, Odd Fellows Rest cemetery had sat firmly between them since 1849. By 1963, the plan to “bypass” Odd Fellows Rest was revived. The Planning Commission announced in August of that year that it sought to purchase “the entire Odd Fellows Rest on the downtown river side of the intersection of Canal st. and City Park ave. and a very small portion of the adjoining St. Patrick No. 2 cemetery.”[14] The City would purchase the cemetery, relocate the remains interred therein, and demolish the remainder in order to connect Canal Street and Canal Boulevard. Like its neighboring cemeteries, Odd Fellows Rest had struggled to transition from the nineteenth century to the postwar era. In 1950, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) hired stonecutter Armand Rodehorst, Sr. as the new superintendant of the cemetery.[15] Rodehorst had worked for fifteen years across the street at Greenwood Cemetery, as a laborer for Samuel Gately. In joining Odd Fellows Rest, he was striking out on his own.[16] Rodehorst developed Odd Fellows much in the same way that other cemeteries had done. He built multi-vault tombs to sell piecemeal and constructed modern, cast-concrete tombs. In 1958, however, Rodehorst died in his home at the age of 56.[17] The economic future of Odd Fellows Rest was left without a helmsman. Thus, by 1963, the Louisiana Grand Lodge was positioned to sell the cemetery property, although “not interested in partial relocation, but in total relocation of the cemetery.”[18] City Council, Mayor Victor Schiro, and the Planning Commission agreed to fund the project. Property on City Park Avenue near Delgado Community College was selected, which the City would purchase and gift to the Odd Fellows for transfer of the cemetery’s remains. City Council purchased a lot “bounded by City Park Avenue, Conti Street, Virginia Street, and St. Louis Street” for the purpose.[19] Yet in a twist of fate perhaps unique to New Orleans and its local politics, a private firm learned of the land purchase and beat the City to the punch. The purchaser, Plaza Towers, Inc., bought the property and, in turn, offered to gift it to the City in exchange for another parcel of municipal land located on Howard Avenue and South Rampart. Unlike the City Park Avenue property, which was purchased only as leverage, the Plaza Towers firm needed the Howard Avenue property in their construction project: the forty-five story Plaza Tower building designed by Leonard R. Spangenberg, Jr. & Associates. This obvious power grab left City Council “irate.”[20]

In August of 2005, flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina effected even the cemeteries of Metairie Ridge. Metairie Cemetery lost its administrative building near the cemetery entrance, and untold tombs were damaged. In 2008, state-owned Charity Hospital Cemetery was converted into a memorial to the lives lost in Hurricane Katrina. The property was excavated and analyzed by archaeologists, and large vaults were erected, clad in reflective black granite. The unidentified and unclaimed remains of 86 hurricane victims were interred at this site, which each year is visited and dedicated on the anniversary of Katrina’s landfall. To learn more about the inspiring, harrowing, and touching story of the Katrina Memorial, please read this fantastic piece by Mary LaCoste in the Louisiana Weekly: “Remembering the Katrina Memorial that Almost Wasn’t.” The Last Days of the Halfway House The Halfway House, once positioned tranquilly along the New Basin Canal but by 2005 instead wedged beside the Interstate 10 overpass, was also damaged in the storm. Beginning in the 1840s as a place of rest and refreshment for carriages en route to Lake Pontchartrain, later a restaurant and jazz hall, then an ice cream parlor, the building was purchased in the 1950s by Orkin Pest Control Company. Abandoned by Orkin in the mid-1990s, by 2005 the property was derelict, its roof partially collapsed. The Halfway House was the property of the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association, held by a long-term lease by the city of New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina, plans were set in motion to convert the adjoining property – once Albert Weiblen’s marble shop – into the new 911 Communications Center for the city. It looked as if the Halfway House would be demolished to make way for a parking lot. Even before 2005, an organization called the Jazz Restoration Society worked with the FCBA and City to secure ownership of the Halfway House, with the goal of restoring it to a restaurant and music hall. Years of infighting, pushing and pulling, and negotiations in the city finally ended in 2009, when the building was declared a landmark and the Society was given permission to step in. But, much like the land deal between the City and Odd Fellows Rest, another shoe had to drop. When an environmental assessment was conducted at the Halfway House, soil tests found that forty years of pesticide storage and disposal left the property unsalvageable by even the best intentions. Despite years of fighting to save the Halfway House, it was demolished in 2010. Conclusion As of this writing, the current road construction project at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is on-schedule and should be finished in one week. Streetcar lines are laid, sweeping across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard. Archaeological assessments and relocation of remains from the cemetery beneath Canal Boulevard have taken place. Soon, the intersection will assume its most recent form, in a place that has held so many forms for one hundred and eighty years. In this series, we have seen this place conform to cultural changes, urban expansion, technological innovation, war, and peace. It is a testament to how imperceptibly dynamic New Orleans cemeteries are – that we can walk through them and feel tranquility and stillness, when in reality they’re shifting, conforming, losing and gaining things that will be held precious by future generations. And there’s even so much we’ve left out! Left out was the Perseverance Lodge No. 13 society tomb in Cypress Grove, hit by lightning twice in the late twentieth century and recently reconstructed by FCBA. Left out was the flower shop on Canal Street beside Cypress Grove, once a hub for chrysanthemums and roses shuttled off to the cemeteries, by the 1990s derelict, and demolished in 2016. The merger of Stewart Enterprises, Inc. with Service Corporation International in 2014 merits its own thousand words on the industrialization of funeral and cemetery industries. Uncountable changes have taken place in this tiny colony of cities of the dead. This retrospect, more than anything, then, has been an overture to recognizing how very important those aspects of our cemeteries which have survived all of this. From Cypress Grove to Chevra Thilim Memorial Park, from Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum to Holt Cemetery, it is impossible to appreciate these relics too much. [1] Samuel Charters, A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 257.

[2] Jerry Strahan, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats that Won World War II (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1994), 49-50. [3] Ibid. [4] “For Sale: Two of the Modern Higgins Industrial Plants and Clinic in New Orleans,” Times-Picayune, November 19, 1945, 17. [5] Times-Picayune, April 11, 19; Times-Picayune, October 6, 1959, 27; Times-Picayune, April 5, 1964, 71; Times-Picayune, February 10, 1964, 45. [6] “Higgins Shipyard,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1972, 44. [7] “Congratulations Delgado,” Times-Picayune, March 4, 1982, 19. [8] “The Modern Way of Burial” was Hope Mausoleum’s official slogan from the 1930s through the 1950s. For example, “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, May 2, 1935, 2; and “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, January 26, 1958, 2. [9] Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 20-21. [10] “Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, October 3, 1954, 15; “Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum – A Report on Progress,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1951, 10. [11] Henri A. Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, Inc., 1981), 108. [12] “Details on Switch of Morrison’s Burial Site Revealed,” Times-Picayune, May 5, 1966. [13] “End to Canal ‘Dog-Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1. I would like to recognize and thank Michael Duplantier for sharing resources and information contained in the (sort of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest section. [14] Ibid. [15] “Odd Fellows Cemetery,” Times-Picayune, December 26, 1950, 41. [16] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1935, Vol. LXI (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1935), 1171; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1938 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1938), 933; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1949 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1949), 1209. [17] “Business, Civic Leader Expires: Rodehorst Rites will be Held Today,” Times-Picayune, September 16, 1958. [18] “Accord on Canal Street ‘Dog Leg’ Plans Possible,” Times-Picayune, November 7, 1963, Section 2, 6; “Lodge to Help on Street Link,” Times-Picayune, August 20, 1963, 7. [19] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [20] “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, June 3, 1964, 1. [21] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [22] Edward J. Branley, New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line (Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 95. This is Part Two in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here. 1841: St. Patrick’s Cemetery At the same time that Americans from the northeast were moving en masse to New Orleans, a separate wave of immigration from Ireland made a great impact on the city. Immigrants fleeing famine and political unrest in Ireland came to New Orleans and settled mostly in what is now the Faubourg St. Mary neighborhood of New Orleans, abutting the Central Business District and what is now the Crescent City Connection bridge. These immigrants formed what is now Irish Channel, although the boundaries of this neighborhood have changed over time.[1] The neighborhood formed from settlement patterns dependent on the construction of the New Basin Canal. In 1833, the Parish of St. Patrick was founded to accommodate Irish Catholics in the neighborhood. By 1840, St. Patrick’s Church was constructed on Camp Street.

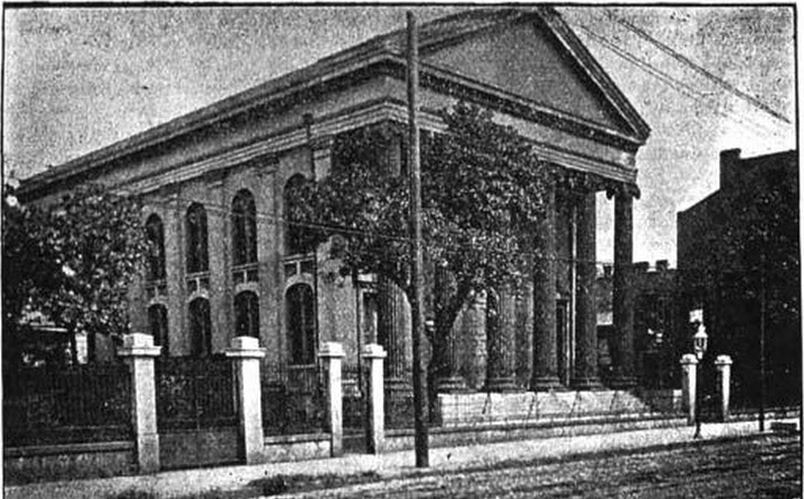

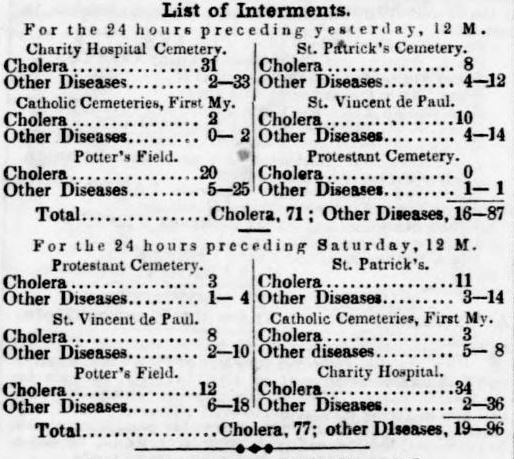

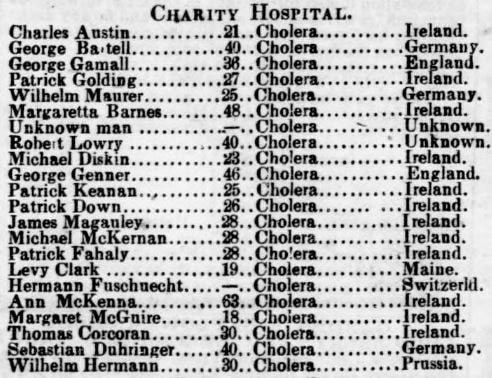

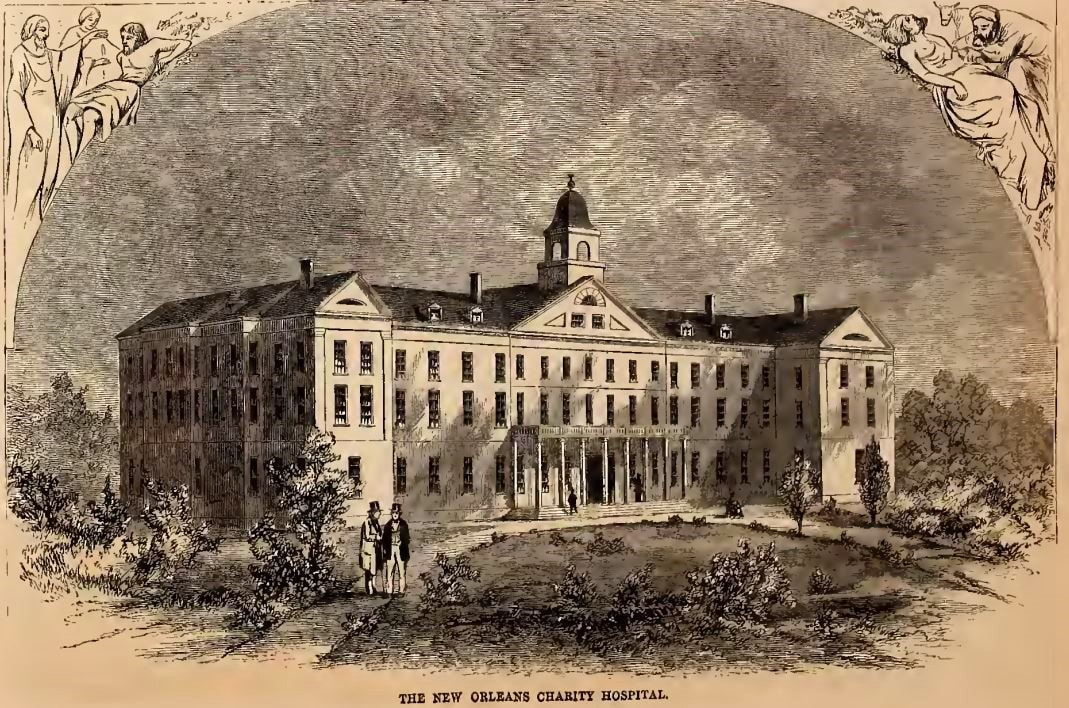

The St. Patrick Cemeteries, so fresh and clean in their snow-white garb and pebbly walks, always attract attention. Here lie the sturdy Irish pioneers who came to New Orleans in the early part of the last century and helped to make her history the proud tale it is… they breathe throughout the spirit of the Catholic faith. Special attention is directed to the beautiful Calvary shrine at the further end of St. Patrick’s No. 1 and the Mater Dolorosa that marks the entrance to St. Patrick’s No. 2.[3] The Calvary statue was designed by then-prominent monument man Charles A. Orleans, consisting of “a wooden cross twenty feet high with life-sized statues of the crucified Christ, Mary Mother of Jesus, His beloved disciple John, and Mary Magdelene. The statues were cast in Paris.”[4] In 1973, in the midst of trends toward community mausoleums, the Calvary was removed to make way for the Calvary Mausoleum. 1846: Dispersed of Judah Cemetery Along with Americans and Irish immigrants to New Orleans, another group of established immigrants and newcomers found their burial place at the end of Canal Street. Jewish people had long lived in New Orleans in small communities, first of primarily Sephardic Jews (of the Spanish-Portuguese tradition) from the Caribbean and England, then later Ashkenazi Jews from Germany and Alsace-Lorraine. These communities first organized in 1828 to found Gates of Mercy congregation, which had a synagogue on Rampart Street near St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Gates of Mercy was an Ashkenazi congregation, and Sephardic Jews in New Orleans sought their own place of worship. This hope was fulfilled in 1846 when organizer Gershom Kursheedt helped aging benefactor Judah Touro found congregation Nefuzoth Yehudah (Dispersed of Judah) in 1846. Dispersed of Judah, a Sephardic congregation, was one of many religious organizations to benefit from Judah Touro’s generous will, which also founded Touro Infirmary, later to become Touro Hospital. In 1881, Dispersed of Judah and Gates of Mercy congregations would merge. The new congregation was eventually renamed Touro Synagogue. In the same year Dispersed of Judah congregation was founded, property adjoining St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2 along Canal Street was purchased for a cemetery. Dispersed of Judah was the second Jewish cemetery in New Orleans. Gates of Mercy had established a cemetery on Jackson Avenue near Saratoga Street in 1828, but this cemetery was demolished in 1957, part of a trend that will be discussed in a later part of this series. Thus, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery is the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. Members of Dispersed of Judah congregation were often tied to English colonial or business interests, arriving in New Orleans from the English-colonized Caribbean or New York. This Anglo-cultural tie, as well as a religious need to bury belowground, allowed Dispersed of Judah to grow into a small version of a northern cemetery. The landscape today retains some elements of this – box tombs and obelisks, trees, and raised monuments. The cemetery is probably best known for the marble monument of Lilla Benjamin Wolf (died 1911), carved into the shape of an empty chair with foot stool. A local story tells the sale of Mrs. Wolf sitting in her chair in life, outside her family’s shop, calling potential customers inside. This may have been a deeply personal choice of monument for the Wolf family, although “the empty chair” was also a common funerary symbol at the turn of the century. 1848: Charity Hospital Cemetery By 1848, Charity Hospital was an institution nearly as old as New Orleans itself. Founded in 1732, the hospital provided care to all patients without regard to race, nationality, religion, or sex. Throughout the nineteenth century, Charity Hospital cared for thousands of newly-arrived immigrants who fell ill after the trans-Atlantic journey, or who were especially susceptible to New Orleans epidemics of yellow fever and cholera.[5]  Charity Hospital's fifth building, in use from 1832 to 1939. Located on Common Street between St. Mary and Girod Streets, it was replaced in the 1930s by "Big Charity," a building designed by Weiss, Dreyfus, and Seiferth, who also designed the Louisiana State Capitol at Baton Rouge. Image from Harper's Weekly, September 3, 1859, via archive.org.

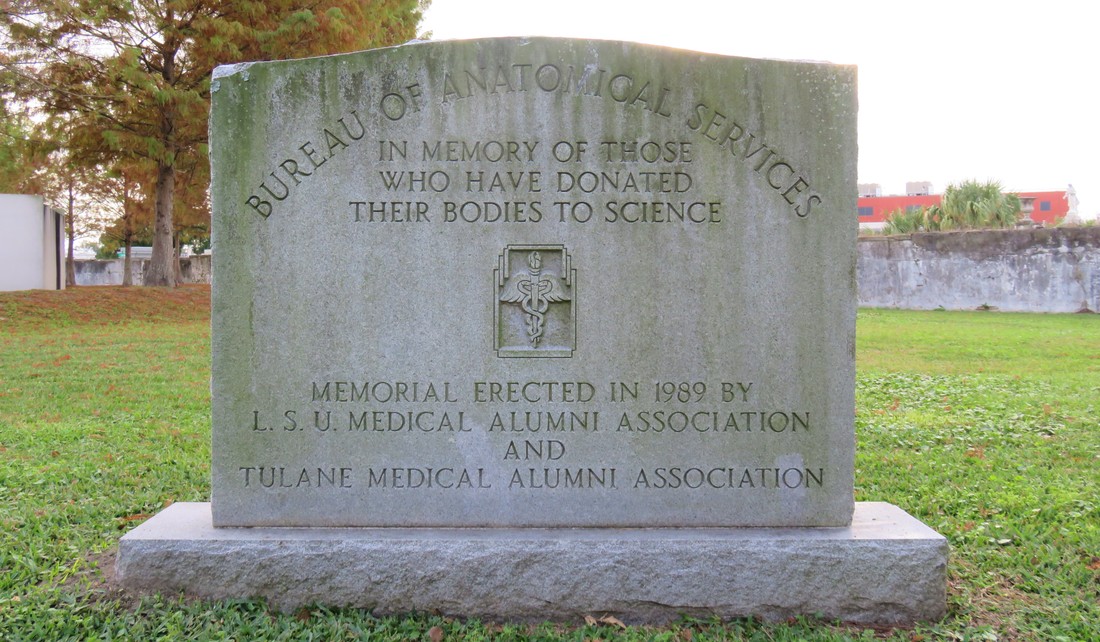

The firemen used axes to demolish the fence to save the [adjoining] St. Patrick’s Cemetery property, but nothing could be done to prevent destruction, and, after the flames had consumed the grass, covered the graves under smoldering ashes, with no crosses or headboards to identify the original plots, nothing was left for the friends or relatives of the dead to distinguish one grave from the other.[7]  Charity Hospital Cemetery in 2003, looking over the fence from St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2 and toward Canal Street. The flags present on the site suggest that it may have recently been mapped using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to identify gravesites. Photo by Dale Boudreaux, via usgenwebarchive.com Charity Hospital Cemetery would receive scores of burials each day during successive yellow fever and cholera epidemics. Later, the cemetery would also receive the bodies of those who had donated their remains in death as medical school cadavers. After Hurricane Katrina, the cemetery would be revised into a new kind of memorial. 1849: Odd Fellows Rest Charity Hospital was the third cemetery to be established at the end of Canal Street. By that time, the land was still overwhelmingly rural, with few structures save the Halfway House and Toll House along the Shell Road, and the towering Egyptian pillars of Cypress Grove. But around the same time Charity Hospital Cemetery was established, another great landmark was in the works. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), a fraternal organization established in England in the 1700s, had founded a local lodge in New Orleans in 1833. The origins of IOOF’s name seem debated; one explanation has been that the “Odd” designation came from the society’s openness to all members despite trade or occupation. The official IOOF website tells a different story: “…it was odd to find people organized for the purpose of giving aid to those in need.” Indeed, the IOOF’s stated purpose is “Visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead and educate the orphan.” The Odd Fellows were also known as the “Three Link Fraternity,” a reference to their motto “Friendship, Love, and Truth,” often symbolized by the three-link chain. By 1858, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana had more than twenty subordinate local lodges, including the Crescent, Teutonia, Howard, Magnolia, Covenant, and Polar Star Lodges, all beneath the IOOF Grand Lodge umbrella. In addition to establishing widows’ and orphans’ assistance, and constructing one, and then another imposing Odd Fellows Hall building, the local Odd Fellows sought to establish their own cemetery by the late 1840s. Odd Fellows cemeteries were a national phenomenon in the nineteenth century, and can still be found in places as disparate as New Jersey, Texas, Nebraska, California, and Oregon. New Orleans Odd Fellows sought to do the same. Previous to this time, the land acquired by respective cemetery owners like St. Patrick’s Church, Charity Hospital, and the Firemen had been allotted using lines of property demarcation corresponded to Lake Pontchartrain and not the Mississippi River, leading to the long lots exemplified best by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1, 2, and 3. These property lines ran across Bayou Metairie at angles, leaving a small triangle of land wedged between St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Bayou Metairie, and Canal Street. In 1848, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana IOOF purchased this small triangle of land for use as their cemetery – the first, but not the last fraternal cemetery at the end of Canal Street.[8] On February 26, 1849, the various Odd Fellows Lodges converged on the Place d’Armes (Jackson Square) to form an “exceedingly beautiful” procession to celebrate the consecration of Odd Fellows Rest.[1] The parade of hundreds was decked in black crape, banners, and emblems of the many symbols recognized by the Odd Fellows. They marched through the French Quarter in a serpentine route, up one street and down another, across Canal Street and through the American Sector (now the Central Business District) where they converged at the New Basin Canal and boarded carriages to proceed up the New Shell Road to the Halfway House.[2] At the Halfway House, the Odd Fellows re-formed their procession, following a carriage drawn by six gray horses and carrying a sarcophagus containing the remains of sixteen Odd Fellows, exhumed from other cemeteries to be re-interred at Odd Fellows Rest. The procession entered through the cemetery’s gate, a granite Egyptian Revival post-and-lintel that mirrored in style if not size the grand entrance of Cypress Grove immediately across Canal Street. Once inside, the parade ended at the center of the cemetery, where a tomb had been prepared. Poems were read and oratories recited, and the remains reburied. The entrance to Odd Fellows Rest would remain at the center of its Canal Street boundary for more than fifty years. The granite entryway was enclosed by two cast-iron gates produced in Spain for the Odd Fellows that portrayed dozens of the Order’s symbols: cornucopia, beehives, globes, books, shepherd’s staffs, stars, axes, and a mother protecting four children. The gates were surmounted by finals depicting the sun and moon, and atop all of this was the perennial Odd Fellows Symbol, the heart-in-hand. In the mid-twentieth century, New Orleans photographer Clarence John Laughlin would capture the gates in their historic context, complete with detail and careful multichromatic paints. By the 1970s, much of the original ironwork had been stolen or lost. Within the walls of Odd Fellows Rest, the cemetery would be populated by hundreds of enclosed wall vaults, belowground burials, high-style tombs, and even a tumulus. In the 1850s, local sculptor and stonecutter Anthony Barret (1803 – 1873) constructed a 48-vault society tomb for the Teutonia Lodge of the Grand Order IOOF. The society tomb, later transferred to Southwestern Lodge No. 42, was designed reminiscent of an Italian loggia, with each arched group of vaults framed by inverted torches carved in marble. The Teutonia Lodge tomb was surmounted by marble urns on each corner of its roof. At the primary façade of the tomb was the piece-de-resistance of the structure: a remarkably ornate marble panel carved with dozens of symbols of the Order, each framed with fine scrollwork carved in relief. At the center of the panel, the protecting mother sits nursing a baby and wrapping her cloak around another child. Anthony Barret was well known for his remarkable stonework, carving some of the finest relief sculptures found in the Lafayette Cemeteries and elsewhere. Even still, the Teutonia Lodge tomb is the greatest artistic accomplishment of Barret’s to survive into the present day. [1] Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma, 172.

[2] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 132-133, 139-140. [3] The New Orleans Picayune, The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: The Picayune, 1904), 152. [4] Leonard Victor Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2004), 33. [5] John E. Salvaggio, New Orleans’ Charity Hospital: A Story of Physicians, Politics, and Poverty (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1992), 35-45. [6] “Second Municipality Council,” Daily Picayune, May 19, 1847, 2. [7] “A Cemetery Blaze: Flames Sweep the Spot where Charity Hospital Dead are Interred,” Times-Picayune, February 27, 1905, 11. [8] An 1833 map of New Orleans from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain shows the intersection of Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal divided into properties belonging to the New Orleans Banking and Canal Company, and illustrates how the property lines correspond with Lake-oriented parcels. A high-resolution of that map is available here. [9] “Consecration of Odd Fellows Rest,” Daily Crescent, February 27, 1849, 1. [10] Ibid. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly