|

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb.

2 Comments

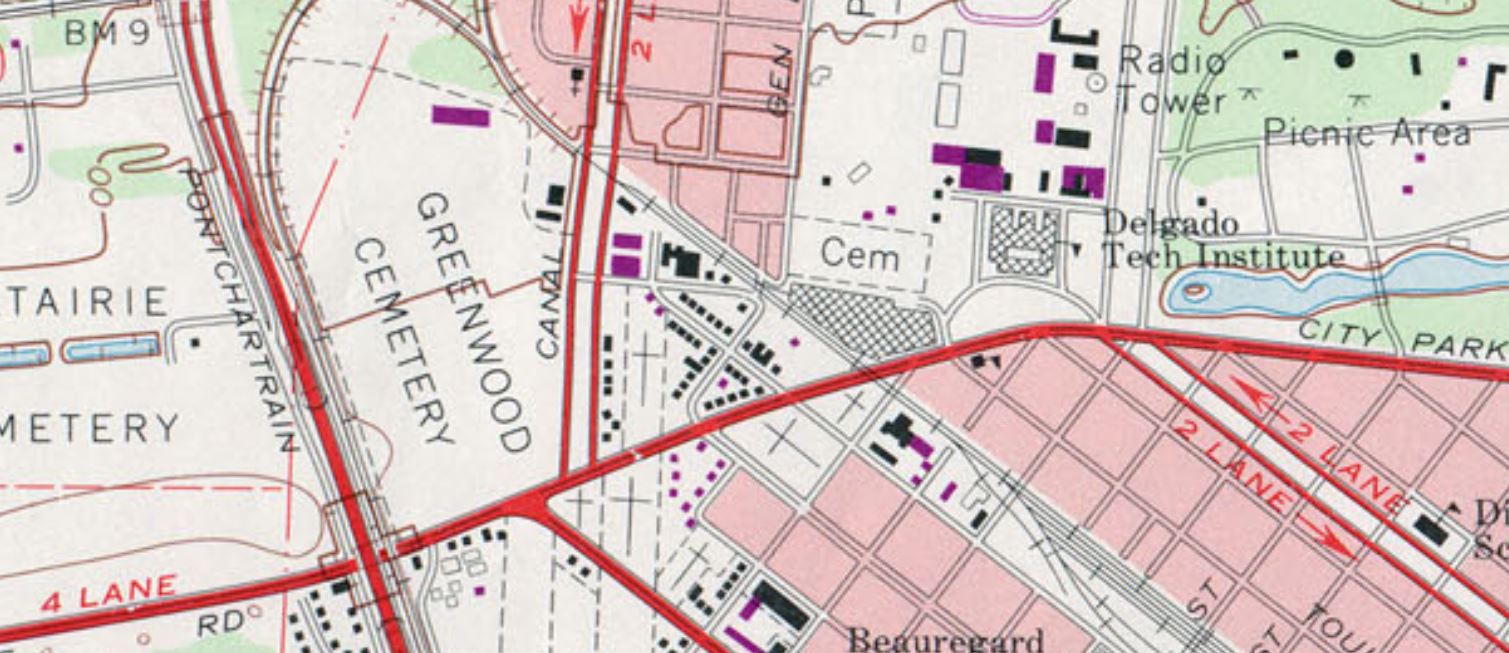

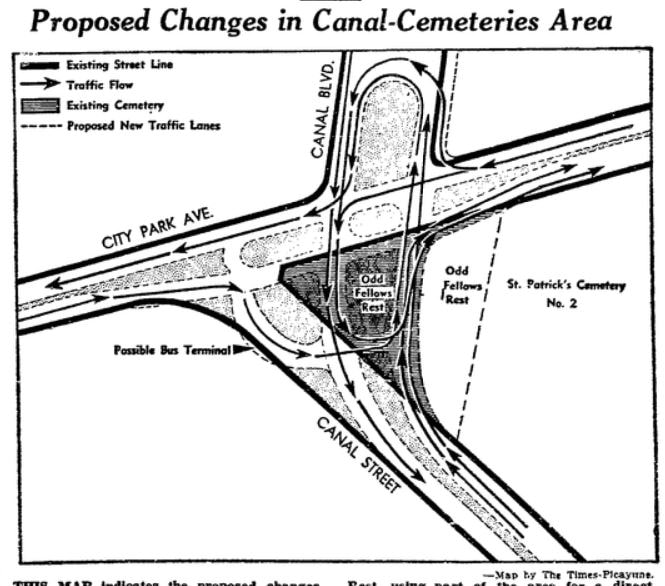

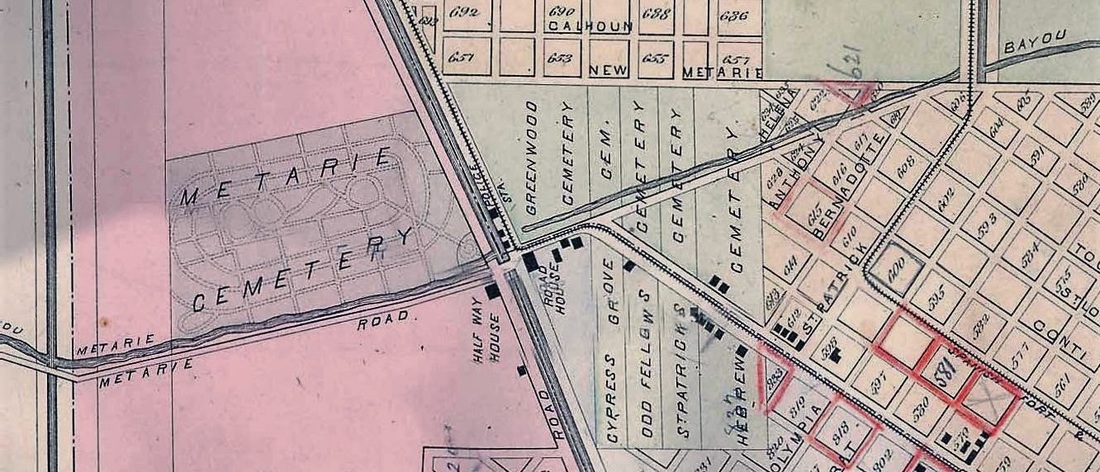

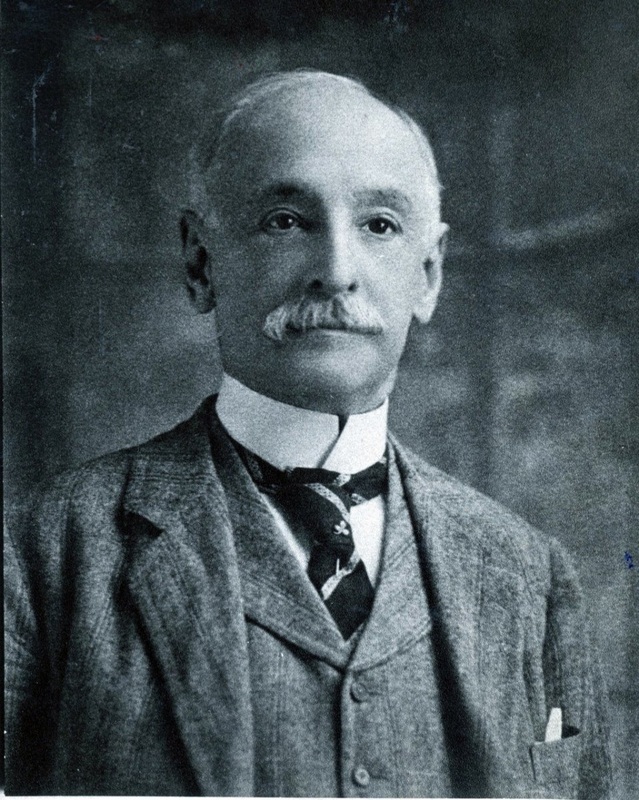

This is the fifth and final part in a five-part series on the historic landscape of City Park Avenue and Canal Street, and its associated cemeteries. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. To start at the beginning of this series, find Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here, and Part Four here. By the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue had undergone a century of extraordinary change. Where once Bayou Metairie meandered westward past acacia trees and a pastoral ridge, now City Park Avenue coasted across the New Basin Canal to become Metairie Road, past the grand monuments of Metairie Cemetery, and into Old Metairie. Where once the Egyptian Revival columns of Cypress Grove stood tall over an undeveloped landscape, now cars rumbled past the monuments and walls of Greenwood Cemetery and Odd Fellows Rest. Jazz blared from the Halfway House beside the New Basin Canal through the 1920s, until the House was converted into an ice cream parlor in 1930.[1] Bayou Metairie had slowly been filled in to accommodate City Park Avenue. To the east, Delgado Central Trades School (now Delgado Community College) was opened in 1921. Beside Delgado, Holt Cemetery remained the municipal potter’s field for New Orleans, but in 1940 the cemetery gained a new neighbor – the Higgins Boat Plant. PTs, Higgins, and the Cemetery Andrew Higgins (1886-1952) is known today in New Orleans as the man who brought the shallow-bottom PT and “landing craft, vehicles, personnel” or “LCVP” boats to the Allied effort in World War II. LCVP boats were used extensively in the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1945, leading then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower to say in 1964 that Higgins had “won the war for us.” Before World War II, Higgins had gotten his start designing shallow-bottom boats that performed well in the Louisiana bayous and other waterways beset by submerged obstacles. But by the late 1930s, Higgins produced new designs that not only could achieve amphibious landings in shallow waters, but were also equipped with ramps to allow swift disembarkation upon landing. These qualities made Higgins Boats imperative to the war effort. In 1940, Higgins Industries constructed a $1.5 million boat-building facility in the least expected of places: far from water, along City Park Avenue, and beside Holt Cemetery. Ever known for his enterprising spirit, Higgins’ City Park plant became the “world’s largest boat manufacturing plant housed under one roof.”[1] The plant took advantage of the Southern Railway line that cut northwesterly across City Park Avenue, beside Masonic Cemetery No. 2. Boats would be manufactured at the City Park plant, which employed thousands of people, and shipped to Lake Pontchartrain for testing. The booming wartime production of the plant left the operation bursting at the seams. Said historian Jerry Strahan of Higgins’ need to expand: “The back of the shipyard was adjacent to Holt Cemetery. Higgins decided to enlarge the plant ‘knowingly and willingly’ by preempting an unused portion of the cemetery grounds. The plant was increased until 40 percent of the new facility was constructed on property to which Higgins held no title, a problem that was unresolved as late as 1947.”[2] Photos of the plant and adjoining Holt Cemetery can be found here under photographs numbered 14 and 21. As early as November 1945, the loss of massive wartime governmental contracts hit the Higgins plant hard. The property was put up for sale.[3] The building at 501 City Park Avenue would have myriad uses over the next thirty-five years – it was a Piggly Wiggly grocery store in 1948, offices for Georgia Pacific Corporation in 1959, and part of the building was used as an art warehouse in 1964.[4] From the 1960s through the 1970s, a van and storage company conducted business in the old plant. In 1972, the building was demolished - its walls, beams, floors, and other items sold for salvage.[5] Finally, in 1982, Delgado Community College opened the Arthur J. O’Keefe Administration Building at 501 City Park Avenue.[6] The architecturally intriguing building remains in the same capacity to this day. In 1964, Holt Cemetery would cease to serve as New Orleans’ potter’s field. The city of New Orleans, under coroner Frank Minyard instead leased a lot from Resthaven Cemetery in New Orleans East for this purpose. This section of Resthaven continues to serve as New Orleans’ indigent burial ground. The American Way of Death After the close of World War II, industries which had boomed forward industrially and technologically looked inward for domestic uses of their innovations. Higgins Industries attempted to this very thing: selling Higgins-designed watercraft for private uses. While to contemporary readers it may seem strange, the same phenomenon took place in the funeral and cemetery industries. Moreover, the clientele of these industries had changed: they were more prosperous, more mobile, and had different values. For 1950s Americans, death was to be confronted with more discretion, privacy, and modernity than had been the case for previous generations. The cultural boom of the 1950s held an inherent disdain for the old-fashioned. This trend is often best exemplified in the scorn held for Victorian architecture during this period. Modern Americans sought urban renewal to wipe away old landscapes. In New Orleans, such sentiments manifested in the rapid construction of community mausoleums, establishment of “memorial park” style cemeteries like Garden of Memories, and the destruction of Girod Street Cemetery. Girod Street Cemetery was established in 1822 at the foot of Girod Street near Liberty Street. By the mid-1950s, the cemetery was bounded by the New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, part of a neighborhood seen as old, blighted, and an obstruction to progress. After repeated attempts by the cemetery’s owner, Christ Church Cathedral, to resurrect the cemetery both architecturally and functionally, it was expropriated by eminent domain to the federal government and the City of New Orleans. The cemetery was demolished in 1957. Girod Street Cemetery was located far from the Canal Street cemeteries, but it held certain cultural and architectural ties to other Protestant-dominated cemeteries like Cypress Grove and St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery. As the process of demolition began, the Huber family which had assumed ownership of St. John’s Cemetery in the 1920s, jockeyed for the contract to relocate the Girod Street remains. This competition involved multiple cemetery craftsmen-turned-cemetery owners and would not be the last time a cemetery operator competed for business with his peers. At the same time Girod Street Cemetery was being demolished, cemeteries at Canal Street and City Park Avenue were modernizing. The first inklings of cemetery stoneworkers turning to cemetery operation began in the 1910s and 1920s. For example, in 1910, stonecutter Albert Stewart assumed ownership of St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street, acquiring it from the Suarez brothers. The Huber family had gained ownership of St. John’s Lutheran Cemetery in the 1920s – and by the 1930s, began construction on Hope Mausoleum, the first community mausoleum in New Orleans. Community mausoleums had gained some traction in the United States beginning in the 1890s and increasingly so in by the time of the Great Depression. In this era, the idea of a large, single-structure facility for burial appealed to cultural ideals of mutual benevolence (indeed, many belonged to fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows) and frugality. In New Orleans, these cultural desires were often met instead with society tombs – large, multi-vault structures within larger cemeteries. Society tombs were New Orleans’ version of community mausoleums, which reflected a more northern aesthetic. It is, then, not surprising that the Huber family gained ownership of German Lutheran St. John’s Cemetery and erected Hope Mausoleum around the historic burial ground. The development almost appears as an extension of St. John’s, Girod, and Cypress Grove Cemetery’s tendency to reflect non-Francophile aesthetics. In the early 1930s, Hope Mausoleum opened, a modestly Art Deco edifice encased in polished marble and touting itself as, “The Modern Way of Burial.”[8] The postwar boom of the 1950s saw a second heyday for community mausoleums, but these mausoleums suited newer cultural norms. The era valued opulence and modernity, sleek, state-of-the-art materials and a dearth of filigree and detail. The funeral and cemetery industries, rising into a new period of lobbying professional organizations, consolidated costs, and property accumulation, responded in kind. Indeed, author Jessica Mitford in her 1963 indictment of the industry, The American Way of Death, compared the contemporary funeral industry to the car industry of the same age: overloaded with space-age fins and baubles.[9] Thus, the new community mausoleum was meant to be an expression of modernity and opulence, and a doing-away with the stodgy funereal rituals and trappings of the past. Into this new market rose the children of Albert Stewart – Frank Sr. and Charles Stewart. Under their business, Acme Marble and Granite Company, the Stewarts purchased land adjoining the north boundary of Metairie Cemetery and set forth to construct a community mausoleum for the age. Completed in 1958, Lake Lawn Mausoleum would be the “the ultimate in modern burial,” with “paneling of rich mahoganies, carpeted floors, custom-built furniture, and rare plants and flowers.”[1] Lake Lawn would be the anti-Girod Street Cemetery. Historic photos suggest that Lake Lawn advertised within the walls of Girod Street, declaring that burials removed from the old Protestant cemetery could be moved to a thoroughly modern location. In fact, the engineer of Girod Street Cemetery’s demolition, Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, did just that. The contents of the Story family mausoleum, relatives of Mayor Morrison, were moved to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum in May of 1956. In the end, though, Hope Mausoleum would gain the contract to re-inter the white burials from Girod Street Cemetery. In accordance with contemporary segregation laws (even in death) Providence Memorial Park in Metairie would receive the African American burials from Girod Street. The torchbearer of urban renewal, Mayor Chep Morrison, would himself in death become part of the struggle between rising cemetery entrepreneurs, and the clash of new and old New Orleans cemetery culture. Shortly before his death in 1957, entrepreneurial monument man Albert Weiblen, who by this time had expanded his business to owning entire quarries in Georgia, purchased the entirety of Metairie Cemetery. His widow Norma maintained this enterprise after Albert’s passing, and when Mayor Chep Morrison perished in a tragic airplane accident in 1964, a standoff ensued between old Metairie Cemetery and modern, neighboring, Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Mayor Morrison had, as mentioned previously, moved his family’s remains from Girod Street Cemetery to Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum. Yet while the new mausoleum was modern, Metairie Cemetery had been the lauded resting place of New Orleans mayors, governors, and Mardi Gras kings (nine, eleven, and more than fifty, respectively[1]). Metairie’s position in New Orleans culture was to be the hallowed resting place of power in all its forms. Presumably to preserve this reputation, Norma Weiblen called Morrison executor William H. Lindsay, Sr. on May 24, 1964, offering the Morrison family very steep discounts on a new tomb in Metairie Cemetery if they would consider moving Mayor Morrison’s burial there from Lake Lawn Park. She added that Lake Lawn Park was a “stinkpot,” and that she “knew [Metairie Cemetery] was where [Morrison] belonged.”[2] Years later, the matter would result in a lawsuit. Morrison was buried in Metairie Cemetery and, in 1969, Stewart Enteprises purchased Metairie Cemetery, renaming the joined properties “Lake Lawn-Metairie Cemetery.” The modernization of historic cemeteries at the end of Canal Street was fueled by the spirit of an era – and a struggle for space. By the 1950s, many of the cemeteries in the area were more than a century old. Furthermore, the city of New Orleans and the suburb of Metairie had grown tightly around them, leaving no room to expand. Community mausoleums were a practical way to capitalize on sellable space. Metairie Cemetery had made such a venture – filling in one of the cemetery’s lagoons to construct Metairie Mausoleum in 1958. In 1964, the various parish-owned Catholic cemeteries in New Orleans would be consolidated under the new New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. Ten years later, the Calvary at the rear of St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1 would be demolished to construct Calvary Mausoleum. In 1969, the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association would open Greenwood Mausoleum. The Jewish cemeteries at the end of Canal Street would also reorganize ownership. In the late 1950s, the Hebrew Burial Association would form to assume ownership of Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, the oldest surviving Jewish Cemetery in New Orleans. With religious restrictions against above-ground burial, the cemetery instead appears to have expanded toward Bernadotte Street in this time, where today a section of modern, 1950s granite monuments stands. In 1973, conservative congregation Chevra Thilim established Chevra Thilim Memorial Park in a small triangle of land bounded by St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2, Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, and Iberville Street. In 1999, Chevra Thilim merged with another congregation to form Shir Chadosh congregation, who retains ownership of the memorial park-style cemetery. Canals, Streetcars, and Automobiles Within cemetery walls, local stonecutters became sales agents and marble increasingly gave way to increased use of granite. No longer the city’s potter’s field, Holt Cemetery became a burial ground for the families of those already interred therein. Outside the cemeteries of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, water and soil gave way to concrete and pylons The New Basin Canal, in service since 1838 and arguably the heart of the cemeteries landscape, was by the 1950s no longer fit for industrial use. As with Bayou Metairie before, the canal was filled in and repurposed for automobile use. In 1958, a new overpass was constructed for City Park Avenue traffic to traverse over the canal, but its use would be short lived. By 1962, sections of the canal nearest to Lake Pontchartrain were filled in and became West End Boulevard. At the end of the wide boulevard’s neutral ground, a civil defense bunker was constructed as a station of command for government in the event of nuclear war. The bunker has been abandoned since the late 1990s, but remains present on West End Boulevard near Robert E. Lee Boulevard. Finally, in 1968, plans that had begun in the 1950s with Mayor Morrison came to fruition and a superhighway was constructed to connect Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Pontchartrain Expressway, part of Interstate 10, was constructed above the filled-in New Basin Canal – replacing high levies and deep water with tall pylons and dipping underpasses. Increased automobile traffic was met with increased automobile infrastructure, but one seemed to continually outpace the other. The roadways as they were in 1968 were complex and disconnected: Canal Boulevard met City Park Avenue, which met Canal Street in a dog-leg which already vexed motorists. The triangular lot of Odd Fellows Rest formed this dog-leg, and in the 1960s, civic eyes turned to eliminate the obstacle. The (sort-of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest As early as 1948, New Orleans’ City Planning Commission recognized the “dog-leg” problem.[13] As automobile drivers increasingly used Canal Boulevard and Canal Street as a commuter route to and from the city, the multiple turns needed to achieve this route caused traffic congestion. While the commission desired nothing more than to connect the two streets, Odd Fellows Rest cemetery had sat firmly between them since 1849. By 1963, the plan to “bypass” Odd Fellows Rest was revived. The Planning Commission announced in August of that year that it sought to purchase “the entire Odd Fellows Rest on the downtown river side of the intersection of Canal st. and City Park ave. and a very small portion of the adjoining St. Patrick No. 2 cemetery.”[14] The City would purchase the cemetery, relocate the remains interred therein, and demolish the remainder in order to connect Canal Street and Canal Boulevard. Like its neighboring cemeteries, Odd Fellows Rest had struggled to transition from the nineteenth century to the postwar era. In 1950, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) hired stonecutter Armand Rodehorst, Sr. as the new superintendant of the cemetery.[15] Rodehorst had worked for fifteen years across the street at Greenwood Cemetery, as a laborer for Samuel Gately. In joining Odd Fellows Rest, he was striking out on his own.[16] Rodehorst developed Odd Fellows much in the same way that other cemeteries had done. He built multi-vault tombs to sell piecemeal and constructed modern, cast-concrete tombs. In 1958, however, Rodehorst died in his home at the age of 56.[17] The economic future of Odd Fellows Rest was left without a helmsman. Thus, by 1963, the Louisiana Grand Lodge was positioned to sell the cemetery property, although “not interested in partial relocation, but in total relocation of the cemetery.”[18] City Council, Mayor Victor Schiro, and the Planning Commission agreed to fund the project. Property on City Park Avenue near Delgado Community College was selected, which the City would purchase and gift to the Odd Fellows for transfer of the cemetery’s remains. City Council purchased a lot “bounded by City Park Avenue, Conti Street, Virginia Street, and St. Louis Street” for the purpose.[19] Yet in a twist of fate perhaps unique to New Orleans and its local politics, a private firm learned of the land purchase and beat the City to the punch. The purchaser, Plaza Towers, Inc., bought the property and, in turn, offered to gift it to the City in exchange for another parcel of municipal land located on Howard Avenue and South Rampart. Unlike the City Park Avenue property, which was purchased only as leverage, the Plaza Towers firm needed the Howard Avenue property in their construction project: the forty-five story Plaza Tower building designed by Leonard R. Spangenberg, Jr. & Associates. This obvious power grab left City Council “irate.”[20]

In August of 2005, flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina effected even the cemeteries of Metairie Ridge. Metairie Cemetery lost its administrative building near the cemetery entrance, and untold tombs were damaged. In 2008, state-owned Charity Hospital Cemetery was converted into a memorial to the lives lost in Hurricane Katrina. The property was excavated and analyzed by archaeologists, and large vaults were erected, clad in reflective black granite. The unidentified and unclaimed remains of 86 hurricane victims were interred at this site, which each year is visited and dedicated on the anniversary of Katrina’s landfall. To learn more about the inspiring, harrowing, and touching story of the Katrina Memorial, please read this fantastic piece by Mary LaCoste in the Louisiana Weekly: “Remembering the Katrina Memorial that Almost Wasn’t.” The Last Days of the Halfway House The Halfway House, once positioned tranquilly along the New Basin Canal but by 2005 instead wedged beside the Interstate 10 overpass, was also damaged in the storm. Beginning in the 1840s as a place of rest and refreshment for carriages en route to Lake Pontchartrain, later a restaurant and jazz hall, then an ice cream parlor, the building was purchased in the 1950s by Orkin Pest Control Company. Abandoned by Orkin in the mid-1990s, by 2005 the property was derelict, its roof partially collapsed. The Halfway House was the property of the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association, held by a long-term lease by the city of New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina, plans were set in motion to convert the adjoining property – once Albert Weiblen’s marble shop – into the new 911 Communications Center for the city. It looked as if the Halfway House would be demolished to make way for a parking lot. Even before 2005, an organization called the Jazz Restoration Society worked with the FCBA and City to secure ownership of the Halfway House, with the goal of restoring it to a restaurant and music hall. Years of infighting, pushing and pulling, and negotiations in the city finally ended in 2009, when the building was declared a landmark and the Society was given permission to step in. But, much like the land deal between the City and Odd Fellows Rest, another shoe had to drop. When an environmental assessment was conducted at the Halfway House, soil tests found that forty years of pesticide storage and disposal left the property unsalvageable by even the best intentions. Despite years of fighting to save the Halfway House, it was demolished in 2010. Conclusion As of this writing, the current road construction project at the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue is on-schedule and should be finished in one week. Streetcar lines are laid, sweeping across City Park Avenue and onto Canal Boulevard. Archaeological assessments and relocation of remains from the cemetery beneath Canal Boulevard have taken place. Soon, the intersection will assume its most recent form, in a place that has held so many forms for one hundred and eighty years. In this series, we have seen this place conform to cultural changes, urban expansion, technological innovation, war, and peace. It is a testament to how imperceptibly dynamic New Orleans cemeteries are – that we can walk through them and feel tranquility and stillness, when in reality they’re shifting, conforming, losing and gaining things that will be held precious by future generations. And there’s even so much we’ve left out! Left out was the Perseverance Lodge No. 13 society tomb in Cypress Grove, hit by lightning twice in the late twentieth century and recently reconstructed by FCBA. Left out was the flower shop on Canal Street beside Cypress Grove, once a hub for chrysanthemums and roses shuttled off to the cemeteries, by the 1990s derelict, and demolished in 2016. The merger of Stewart Enterprises, Inc. with Service Corporation International in 2014 merits its own thousand words on the industrialization of funeral and cemetery industries. Uncountable changes have taken place in this tiny colony of cities of the dead. This retrospect, more than anything, then, has been an overture to recognizing how very important those aspects of our cemeteries which have survived all of this. From Cypress Grove to Chevra Thilim Memorial Park, from Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum to Holt Cemetery, it is impossible to appreciate these relics too much. [1] Samuel Charters, A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 257.

[2] Jerry Strahan, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats that Won World War II (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1994), 49-50. [3] Ibid. [4] “For Sale: Two of the Modern Higgins Industrial Plants and Clinic in New Orleans,” Times-Picayune, November 19, 1945, 17. [5] Times-Picayune, April 11, 19; Times-Picayune, October 6, 1959, 27; Times-Picayune, April 5, 1964, 71; Times-Picayune, February 10, 1964, 45. [6] “Higgins Shipyard,” Times-Picayune, August 12, 1972, 44. [7] “Congratulations Delgado,” Times-Picayune, March 4, 1982, 19. [8] “The Modern Way of Burial” was Hope Mausoleum’s official slogan from the 1930s through the 1950s. For example, “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, May 2, 1935, 2; and “Hope Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, January 26, 1958, 2. [9] Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 20-21. [10] “Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, October 3, 1954, 15; “Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum – A Report on Progress,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1951, 10. [11] Henri A. Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, Inc., 1981), 108. [12] “Details on Switch of Morrison’s Burial Site Revealed,” Times-Picayune, May 5, 1966. [13] “End to Canal ‘Dog-Leg’ Urged,” Times-Picayune, August 11, 1963, 1. I would like to recognize and thank Michael Duplantier for sharing resources and information contained in the (sort of) Battle for Odd Fellows Rest section. [14] Ibid. [15] “Odd Fellows Cemetery,” Times-Picayune, December 26, 1950, 41. [16] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1935, Vol. LXI (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1935), 1171; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1938 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1938), 933; Polk’s New Orleans City Directory 1949 (New Orleans: R.L. Polk & Co., 1949), 1209. [17] “Business, Civic Leader Expires: Rodehorst Rites will be Held Today,” Times-Picayune, September 16, 1958. [18] “Accord on Canal Street ‘Dog Leg’ Plans Possible,” Times-Picayune, November 7, 1963, Section 2, 6; “Lodge to Help on Street Link,” Times-Picayune, August 20, 1963, 7. [19] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [20] “Council Irate at Land Deal: City Officials Criticized for Failure to Buy,” Times-Picayune, June 3, 1964, 1. [21] “Cemetery Head Petitions Court,” Times-Picayune, August 1, 1968, 9. [22] Edward J. Branley, New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line (Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 95. Part Two of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. Find Part One here. In the 1840s, Cypress Grove Cemetery developed into the landscape its founders envisioned: tree-lined and populated with tombs of the finest order. It also gained company as St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Charity Hospital Cemetery, and Odd Fellows Rest were all established between 1840 and 1850. There at the corner at what is now Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Cypress Grove was part of a pastoral scene: barges floating up Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal, visitors strolling the gardens at the Halfway House, and rail cars pulling up right to the cemetery gates, unloading mourners and the bodies of the mourned.[1] Between its founding in 1840 and the turn of the century, Cypress Grove would become the final resting place of many famous and infamous New Orleans characters. Northern-born transplants to the city would combine New Orleans tomb architecture with the styles and materials they were accustomed to. Firemen would memorialize their fallen brethren within the cemetery’s marble-clad walls. Much of the incremental detail of the cemetery at its height, though, has weathered away from its present-day appearance. It’s easy to miss this historic garden cemetery for its modern lack of trees. But with historic research and a keen eye, it’s possible to rediscover Cypress Grove’s historic grandeur. Firemen, Northerners, and Protestants Cypress Grove was the first fraternal cemetery in New Orleans. All other cemeteries founded up to 1840 belonged either to the Catholic parishes (except Protestant Girod Cemetery, belonging to Christ Church Cathedral) or to each respective municipality (i.e. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1). Many other fraternal organizations, including other firemen’s organizations, would found their own cemeteries over the course of the nineteenth century. Cypress Grove was not intended for the exclusive burial of firemen. It served all New Orleanians seeking burial, if they could purchase a plot, and many who could not. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (present-day Canal Boulevard) was contracted by the City of New Orleans for indigent burial, even after Charity Hospital Cemetery was established in 1848.[2] While Catholics in New Orleans had many cemeteries from which to choose, Protestants had only Girod Street Cemetery and the municipal cemeteries. Perhaps it was simple economics that caused so many Northern-born Protestants to buy property in Cypress Grove. It may also have been caused by cultural interaction between the Firemen (many of whom were also non-native New Orleanians) and others who joined them as newcomers in the Crescent City. In any case, the great majority of historic burials in Cypress Grove denote birth in northern climes such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and others. The Firemen’s Charitable Association fell into this market easily. Stonecutters whose work featured mostly in Girod Street Cemetery, such as long-time Girod Street sexton Horace Gateley, executed tombs and tablets in Cypress Grove as well. Gately himself, who drowned in at Isla del Padre, Texas in 1867, is buried in adjoining Greenwood Cemetery. The FCA even advertised in-ground burial in Cypress Grove. While in-ground burial occurred in nearly every cemetery in the city, FCA was the only cemetery owning body to advertise it – plainly appealing to newcomers with a distaste for Continental-inspired above-ground tombs.[3] When Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957, Cypress Grove became a de facto artifact of what the Protestant cemetery may have looked like. Simpler, sarcophagus-style tombs with accents placed more on great obelisks and sculpture than on Greek acroteria or Baroque scrollwork dotted the aisles of both Girod and Cypress Grove. What few photos of Girod Street Cemetery remain even suggest a few duplicate tombs between both cemeteries: including the now headless and armless tomb statue and tomb of Henrietta Sidle Davidson (died 1881) and another tomb in Girod Street. Philadelphia brick, New Hampshire granite, and other Anglo-inspired tastes contributed to the budding landscape of Cypress Grove.

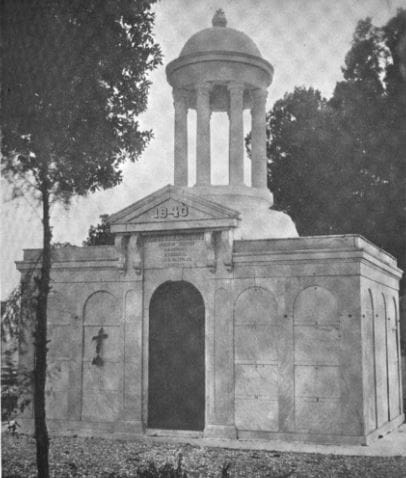

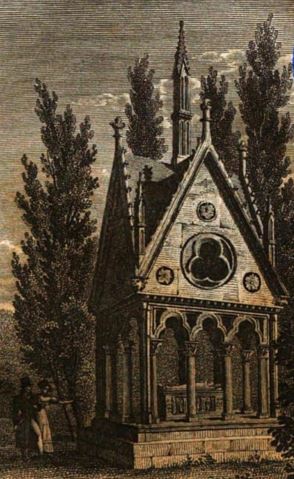

Mr. [S.T.] Jones placed a closely sealed bottle in the box, containing the constitution and list of members of this efflisient [sic] company, the daily newspapers of the city, and the various coins of the country. This was also embedded in mortar, the cover put on, and the whole covered with solid masonry, upon which the corner stone was laid. The beauty of the day, the solemnity of the occasion, and the mournful memories engendered by the scenes around, all contributed to give the ceremony a peculiar interest.[5] The tomb of Perseverance Lodge No. 13 dominated the entrance of Cypress Grove Cemetery then as it does now – a large terra cotta cupola with ionic columns and a cast-iron finial at its dome was constructed atop the tomb roof. At the center of its primary façade, an entrance was likely constructed which was enclosed by cast-iron doors. Above this door were marble brackets and a Classical pediment. The tombs of Philadelphia Fire Engine and Eagle Fire Company were tucked into the front corners of the cemetery. Each built identically, with marble-clad masonry and large urns and finials, they were each enclosed with iron gates, each within the line-of-sight of the Irad Ferry monument. Masterpieces in Marble and Granite Other societies in addition to fire companies would build their tombs in Cypress Grove, most notably the Chinese tomb and Baker’s Benevolent Association tomb. But Cypress Grove would make its mark in the number of great family tombs that populated its aisles. The sarcophagus tomb is one of the most notable artifacts of funerary architecture in New Orleans cemeteries, and in Cypress Grove this was no different. Built of brick and clad in marble pilasters, cornicework, and sculptural elements, the sarcophagus tombs of the McIlhenny, Davidson, Johnston and Walker tombs are examples of the dozens of this burial type found in Cypress Grove. Built by stonecutters like Anthony Barret, James Reynolds, and Newton Richards, they represented the English-speaking stonecutter’s take on a burial style often associated with Creole artisans. The French-speakers were present in Cypress Grove, as well. Sarcophagus tombs by signed by Florville Foy are present beside the work of New Orleans-born Jewish stonecutter Edwin I. Kursheedt. Renowned French-born cemetery architect J.N.B. de Pouilly designed two of the best-known tombs in Cypress Grove: those of Maunsel White and Irad Ferry (constructed by Monsseaux and Richards, respectively).

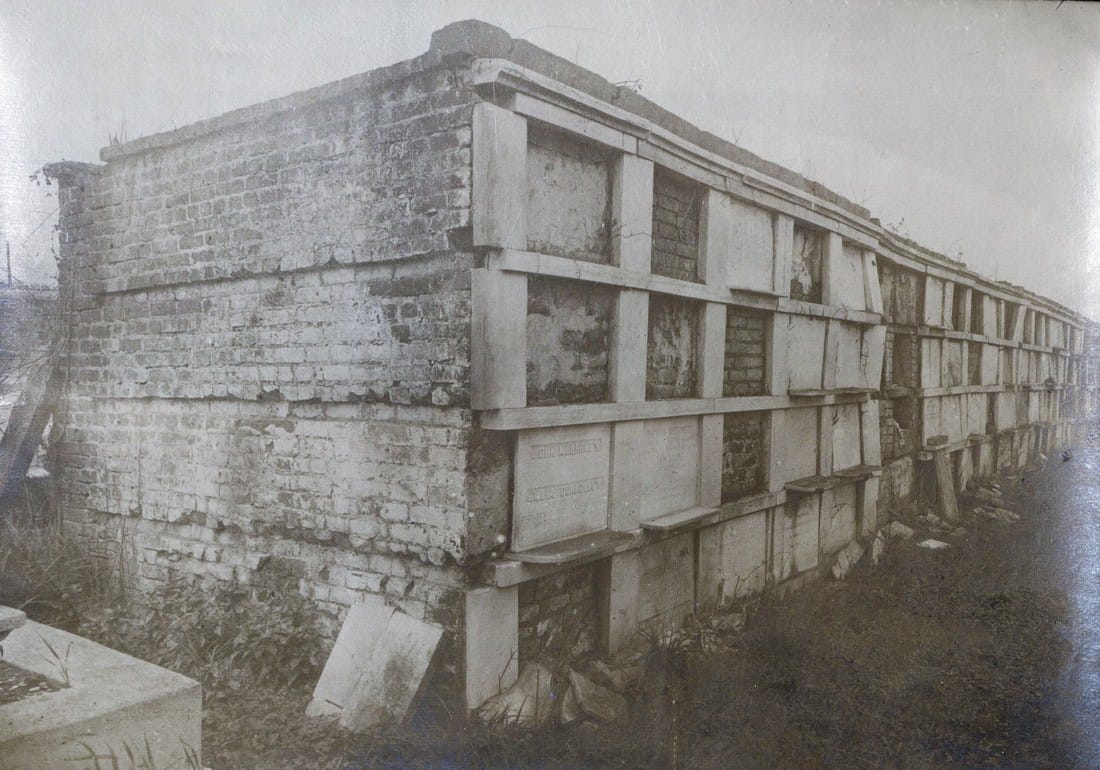

The only remaining example of this style of historic tomb construction lies not in Cypress Grove but in Metairie Cemetery – the Duverje family tomb, constructed between 1808 and 1820 and moved from the family cemetery in Algiers in 1916, retains such acroteria. They are the last of their kind in New Orleans cemeteries. Then and Now After 1945, New Orleans cemeteries underwent a seismic shift in management, industry, and trade. The monument industry had been slowly becoming a national affair managed by large companies – a shift that reached New Orleans after World War II. Over the years, most cemeteries abandoned the employ of the cemetery sexton who traditionally cared for the grounds on a daily basis. Stonecutters, who had often served as sextons, adapted and became cemetery owners and dealers of nationalized products. Technology changed the way tombs were built, repaired, and maintained. This shift affected every cemetery in New Orleans. In the Catholic cemeteries, it led to the consolidation of parish burial grounds into the incorporated New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. In municipal cemeteries, it meant a transfer of management to overstretched city departments that cared for publicly-owned buildings and parks.[7] In the fraternal cemeteries, it meant a consolidation of duties and a new focus on sellable space to accommodate budget shortfalls.[8] With population movement to the suburbs and elsewhere, tombs were less likely to be cared for by their owners. With no sexton to manage the landscape, small issues with tombs became larger problems, often solved in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Storms like Camille, Betsy, and Katrina flooded Cypress Grove Cemetery, killing many of the surviving trees. Those who entered the monument trade after 1950 were much more familiar with new technologies than old materials. Old problems, then, were solved in new ways. In the 1960s, when the marble facing of the extensive wall vaults at Cypress Grove began to sag away from their brick substrate, the decision was made to remove the marble instead of repair it. When landscaping tumuli was too labor intensive, the sod was stripped from their structures, leaving cement-patched, igloo-like bodies behind. Herbicides like RoundUp were selected to replace arduous mowing, damaging masonry and causing grassy root structures to erode, leaving deep ruts which can destabilize walls and tombs. Alternately, trees which lent such a rural feel to Cypress Grove eventually overgrew their root structures, tipping walls and capsizing tombs. All the while, the responsibility of families to care for and repair their own cemetery property became anachronistic in an era of new innovations and perpetual care. The cultural forces that created Cypress Grove had transformed, with the role of the fraternal society somewhat supplanted by the rise of Social Security and insurance companies; the rural cemetery now firmly at the edges of the metropolis. New Orleans cemeteries in general are prized for their historic value, but the value of their maintenance and preservation may exceed that interest from many sides. Yet Cypress Grove remains, its Egyptian columns rising above Canal Street and City Park, where once the bayou and the railroad met. It may be difficult to see it, but with a conscientious eye and a little history, its lost landscapes can be found. [1] “Passenger and Freight Barges on the New Canal,” Daily Picayune, January 1, 1846, 4; Leonard V. Huber, Peggy McDowell, Mary Louis Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Press, 2004), 30-35; At least one duel also took place in front of Cypress Grove’s gates, between former state senator Waggaman and a former New Orleans mayor Prieur, Daily Picayune, March 11, 1843, 2.

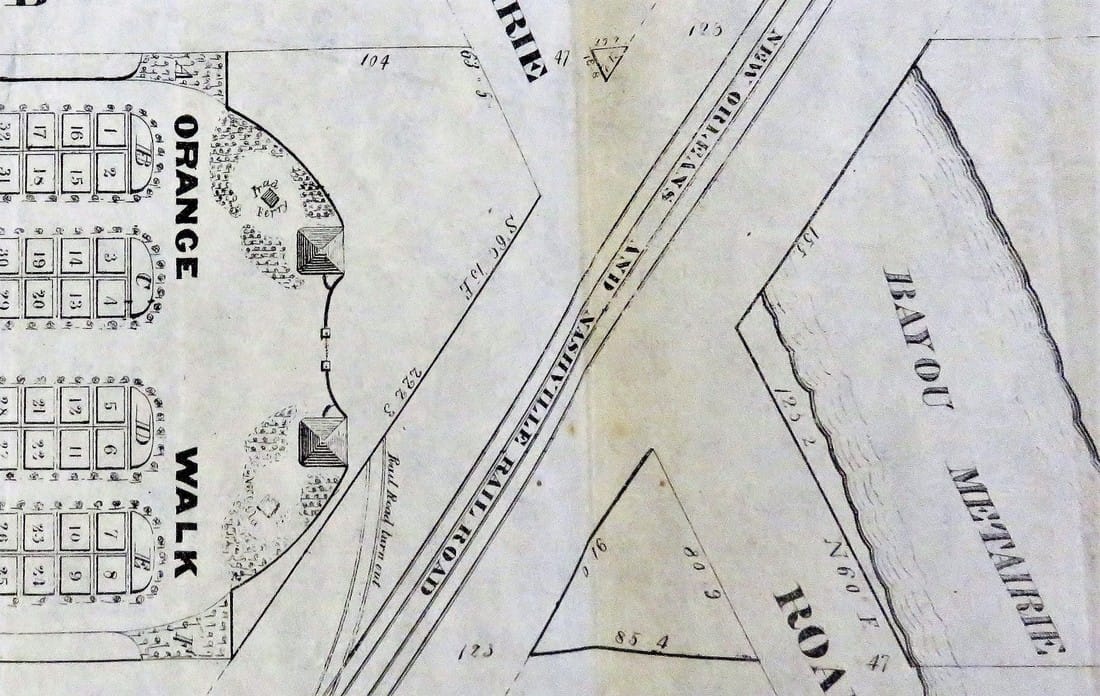

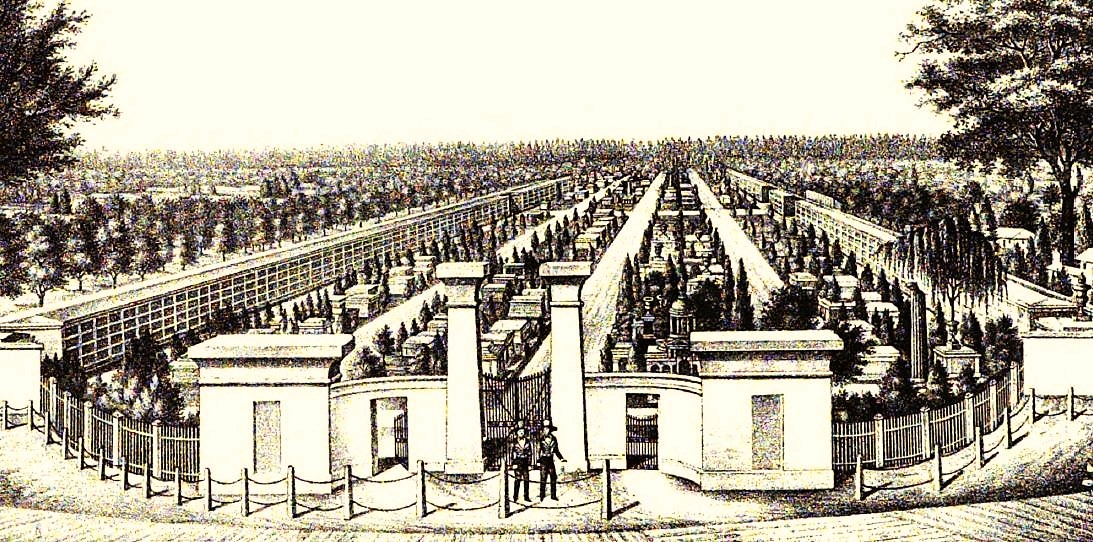

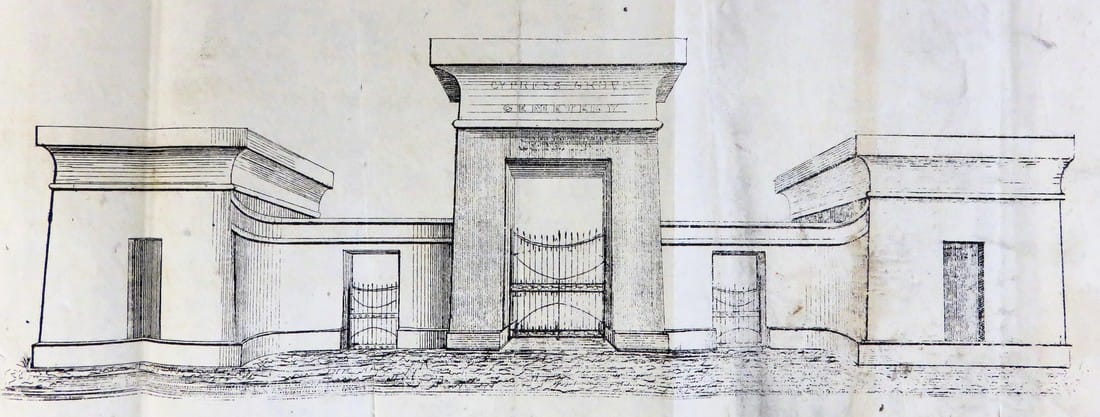

[2] Daily Picayune, April 21, 1846, 2. [3] “Cypress Grove Cemetery,” Daily Picayune, September 15, 1842, 2. Full text: “CYPRESS GROVE CEMETERY. A portion of this rural cemetery having been appropriated for interments in GRAVES, application can be made at the Firemen’s Insurance Office; to M.C. Quirk & Sons, or Mr. Monroe, Undertakers. The Superintendent will also receive at the ground any corpse for interment, on payment of $5 for grown persons and $3 for children. GEORGE BEDFORD, President F.C.A.” [4] “Grand Fancy Dress Ball,” Daily Picayune, February 26, 1852, 3; “Fireman’s Funeral,” Daily Picayune, August 14, 1847, 2. [5] “The City: An Interesting Ceremony,” Daily Picayune, January 3, 1854, 1. [6] Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1855 (New Orleans: Printed at the office of the Picayune, 66 Camp Street, 1855), xiv. [7] Pie Dufour, “Old Cemetery Getting New Look,” Times-Picayune, November 10, 1968. [8] In Cypress Grove, sexton and stonecutter Leonard Gately was instrumental in developing sections into sellable space. Daily Picayune, April 12, 1959, 154. Part One of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. The foot of Canal Street at City Park Avenue is surrounded by cemeteries. At one end, the bronze statue of the Elks Lodge tumulus presides over ever-bustling traffic - right now, in December, the Elk has been decorated with a festive red nose. Facing the intersection from another side is the tall edifice of Odd Fellows Rest. The entrance gate of Cypress Grove stands out even in the grandiose company of these monuments. Comprised of two gatehouses and towering Egyptian Revival pillars, the gate has stood longer than the Elk, the Odd Fellows, or any other cemetery in the area. Within these gates is the oldest rural cemetery in New Orleans. Cypress Grove’s significance is self-evident – its wide avenues showcase example after example of high funeral architecture, of stories that strike the heart of the New Orleans history. But there’s another story among the thousands of tombs in the cemetery. It’s the story of a landscape now obscured by time, of what it used to mean to walk through these aisles. Beyond the mowed grass and paved paths is evidence of what once was a lush, tree-lined landscape on par with the garden cemeteries of the northeast. If you look hard, you can still find it there. The Firemen’s Cemetery Cypress Grove was founded in 1840 by the Firemen’s Charitable Association (FCA), now known as the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association (FCBA). The Association was organized in 1834, about five years after the first New Orleans volunteer fire companies formed. Originally, the Association served in a manner similar to other mutual aid societies: providing social and financial support to the city’s volunteer firemen. Within its first decades, however, the Association became the fire department itself. Until the city switched to a paid fire department in 1892, the Association was responsible for all firefighters in New Orleans – and all firefighters were volunteers.[1] The tale of the founding of Cypress Grove is one well-known to cemetery lovers in New Orleans. On New Year’s Day 1837 while carrying out his duty with Mississippi Fire Company No. 2, thirty-five year-old Irad Ferry perished in a fire on Camp Street. Dubbed the “the first martyr” of the newly-formed fire department, Ferry was venerated with a public funeral and a large memorial march. He was originally laid to rest in Girod Street Cemetery. Along with relief services for their members, benevolent societies of this time provided burial benefits to their members. The Firemen’s Charitable Association was no different, and considered purchasing a section of Girod Street Cemetery for that purpose with plans for Ferry’s monument to be built at its center. But in 1838 the death of Destrehan plantation owner Stephen Henderson widened the Association's prospects. In addition to multiple provisions regarding people enslaved by Henderson, the will specified large bequeaths to religious and social charities, and $500 per annum to the Firemen’s Charitable Association.[2] On Sunday, April 25, 1840, a nearly one thousand firemen, clergy, and prominent citizens marched through downtown New Orleans, each wearing mourning bands and a few carrying urns representing the ashes of their martyred comrades. At Canal Street, they boarded train cars and traveled to Cypress Grove Cemetery, where they re-interred the remains of Irad Ferry beneath a great monument designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and constructed by stonecutter Newton Richards. In a nearby tomb constructed for this purpose, the remains of eleven additional firemen were buried.[3] The Rural Cemetery At its founding in 1840, Cypress Grove became the sixth active cemetery in New Orleans, and the only cemetery at the lake-side foot of Canal Street.[4] Its predecessors were decidedly urban in design: dense, utilitarian though beautiful, and without significant landscaping. A possible exception to this rule was Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, located in what would become the Garden District. Lafayette No. 1 has been referred to as a “transition” cemetery between urban and rural model cemeteries. But even this cemetery was squeezed into a single city block, with no room for the rolling greenery that had become popular in American cemetery design by 1840.[5] Cypress Grove was destined to become something different. Enormous in land area by contemporary New Orleans standards, it was conceived by relative newcomers to the New Orleans Francophile aesthetic. Members of the FCA were often northern-born – for example, Irad Ferry was from Connecticut – and thus influenced by English sensibilities. The Americans brought with them new ideas for cemeteries. They were inspired by what they saw at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and many more. These were cemeteries that were designed instead of planned, with undulating pathways that strolled past weeping willows and reflecting pools. This was the rural cemetery movement, a great shift in the history of cemeteries that would change the American perception of death forever. The rural cemetery movement arose in the northeastern United States as a result of the expansion of cities. Advances in industrialization within the urban landscape created in city-dwellers a longing for the countryside. Furthermore, this same industrialization advanced the American middle class in such a way that recreation was newly defined. Inspired by English landscape design, the rural cemetery was the predecessor to the public park – in fact, Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed one such cemetery in California. This shift in the appearance and purpose of cemeteries coincided with many American cultural movements like Romanticism and the “beautification of death period.” The Firemen’s Charitable Association was certainly aware of this trend. In addition to the explicit use of the term “rural cemetery” in FCA planning documents, the Association expressed a disdain for contrasting urban cemeteries: It would seem almost superfluous to set for the advantages of this rural cemetery. The rapid growth of our city has already encroached upon the tombs of its fathers, and the sacred relics of the dead have been compelled to give way to the cold and selfish policy of speculators, and the intrusion of business; and the solemnity of the grave yard is disturbed by discordant shouts of merriment, and the baleful proximity of the dissolute.[6] If there was any question as to whether the FCA was directly influenced by the rural cemetery movement, one must note that the iconic Cypress Grove entrance gate is a near-exact facsimile of the gate at Mount Auburn. The Cemetery at the Half-Way House For those in FCA who wished Cypress Grove to be a truly rural cemetery, a better location could not have been chosen. The new cemetery was situated at the confluence of vital infrastructure lines: the New Basin Canal and Shell Road, Bayou Metairie, and rail lines at Canal Street. Although the area was an important checkpoint in travel through the area, it was largely undeveloped. One map from 1849 describes the area as a “ridge covered with live oak, persimmon, liriodendron, pecan, wild cherry, interspersed with acacia trees.” The cemetery itself would have, in its own way, water features much like the rural cemeteries it emulated. Early descriptions of the cemetery plan boast “frontage” on both the New Basin Canal and Bayou Metairie. In fact, Cypress Grove Cemetery once straddled Bayou Metairie (today City Park Avenue). The bayou divided Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 1 (present-day Cypress Grove) and Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, a potter’s field now covered by Canal Boulevard. The location of the cemetery not only suited the rural aesthetic but also the new role of the cemetery as a venue for picnics and outings. The Shell Road, which ran alongside the New Basin Canal toward Lake Pontchartrain, was a popular day trip for visitors and locals alike.[7] The Half-Way House and Road House were located at the meeting of the Shell Road and Bayou Metairie – both places of rest, refreshment, and entertainment located at the midway point between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, further cementing Cypress Grove’s destiny as a park-like destination. Growth and Change Those who were drawn to own tombs and lots after 1840 chose Cypress Grove for its bucolic location, wide aisles, and landscaping. In its first twenty years, the cemetery would be filled with some of the grandest architecture New Orleans craftsmen could offer. Its aisles, all named after trees and plants, would bristle with their namesakes shading each pathway. The finest cast iron fences would encircle family tombs clad in marble and Pennsylvania brick. Cypress Grove became, in some ways, an extension of Girod Street Cemetery. Protestants and other non-Catholics sought property within its walls, bringing their taste in obelisks and urns with them. Cypress Grove became home to the second tomb for traditional Chinese burials in New Orleans. The Slark and Letchford families built two tombs inspired by stately Gothic spires along the cemetery’s marble-clad side wall vaults. Cypress Grove would not be alone at the confluence of bayou, canal, and railroad for long. In the same year Cypress Grove was founded, St. Patrick’s Cemetery No. 1 was established. Cypress Grove would be joined by Greenwood Cemetery, Odd Fellows Rest, Dispersed of Judah and other Jewish cemeteries, Charity Hospital Cemetery (now Katrina Memorial), and Masonic Cemetery No. 1. In 1872, Metairie Racetrack would be converted to Metairie Cemetery, and Cypress Grove would be supplanted as the great rural cemetery of New Orleans. One hundred seventy-five years after Cypress Grove’s dedication, there are twelve cemeteries clustered near the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The New Basin Canal was filled in the 1960s and replaced by the Pontchartrain Expressway. Metairie Bayou has been filled and City Park Avenue widened atop it. The Half-Way House and other former New Basin Canal structures were demolished in recent decades. Today, the New Orleans Emergency Communication District buildings are located at the site. Cypress Grove may not be so easily recognized for what it once was. Its trees are mostly missing, replaced by deep ruts in sod where herbicide has taken hold. Many of its great structures have changed or completely disappeared – tumuli stripped of their grassy knolls, wall vaults stripped of their marble facing. Next blog post, we dive deeper into the architectural history of specific tombs and structures in Cypress Grove Cemetery and how they have changed over time. [1] Thomas O’Connor, ed. History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FMBA, 1890), 54-57.

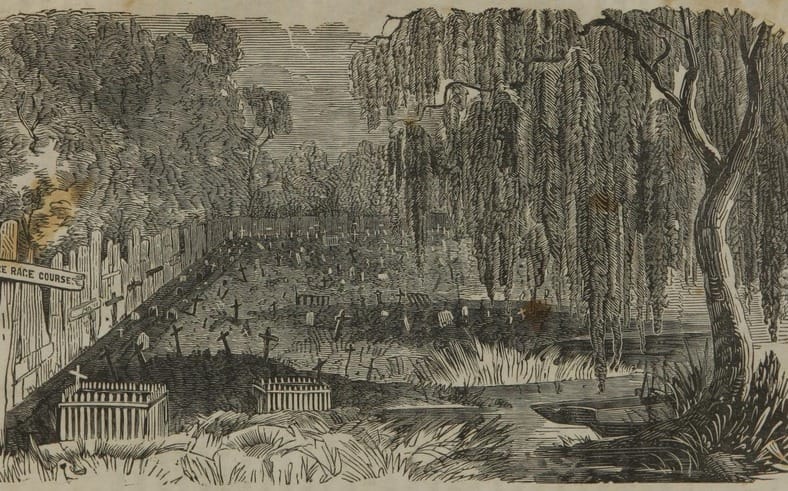

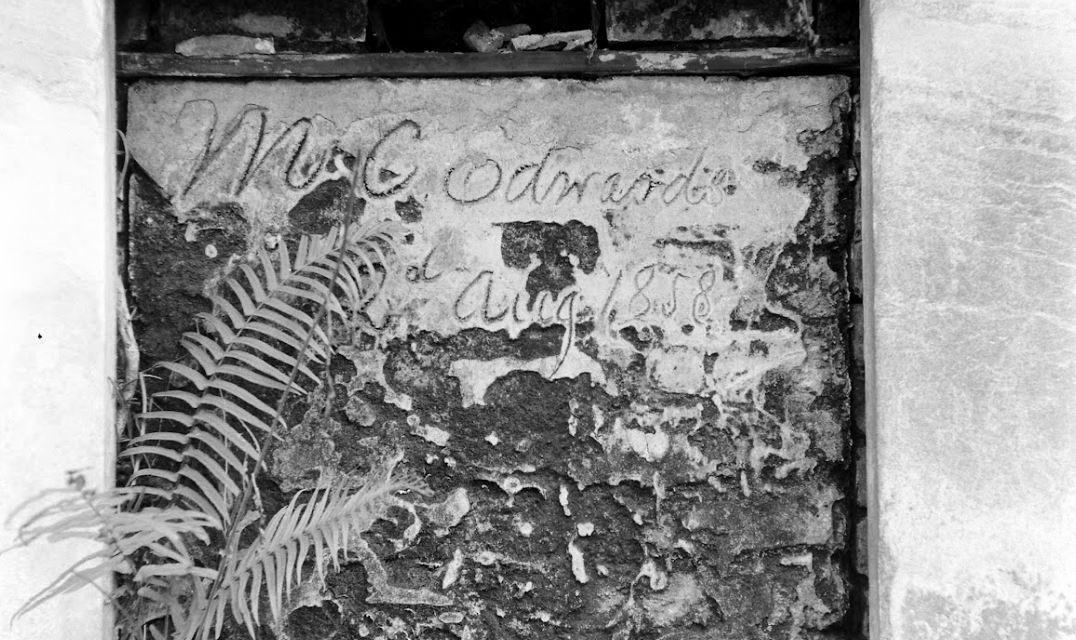

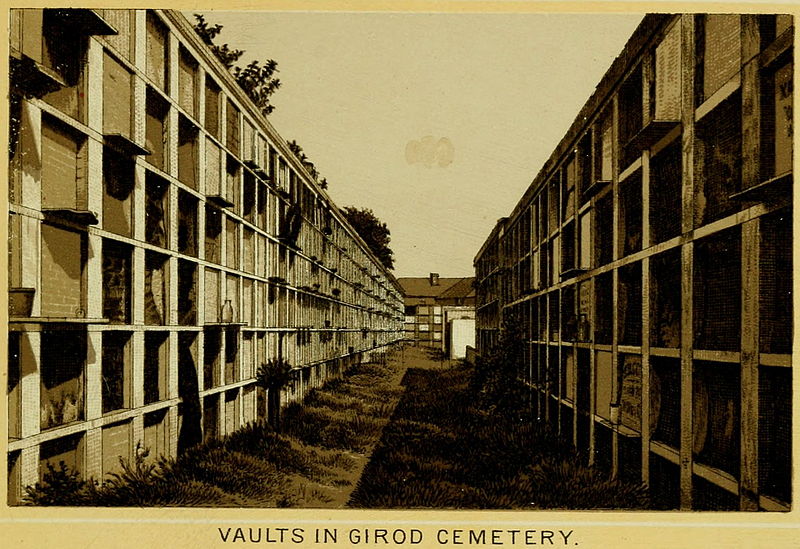

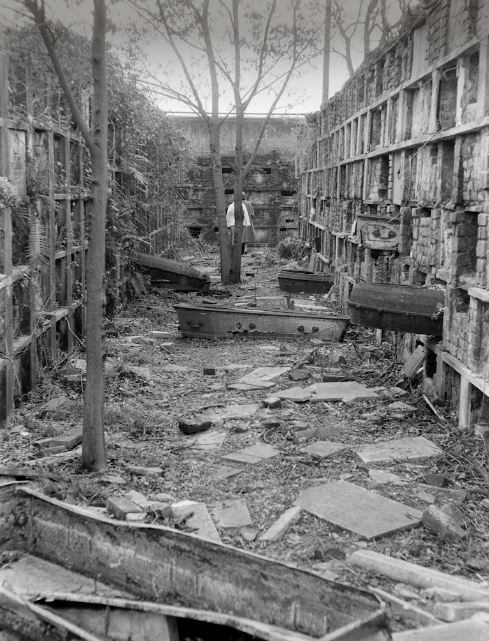

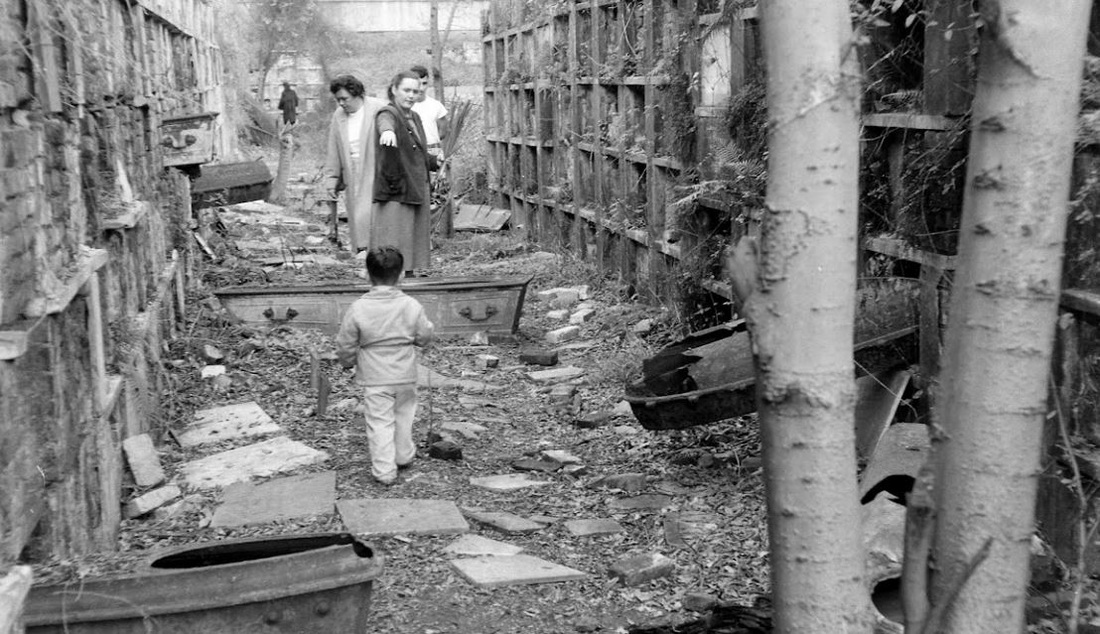

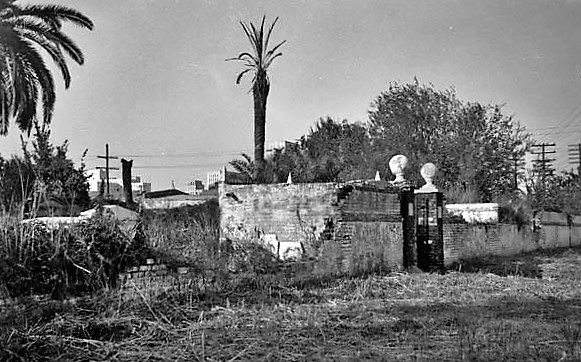

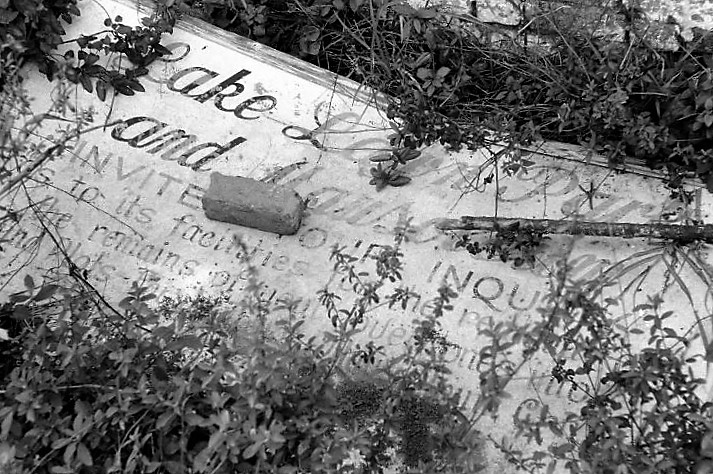

[2] Ibid., 65-70; “Mr. Henderson’s Will,” Daily Picayune, March 17, 1838, 1; Although unrelated to Cypress Grove, the will of Stephen Henderson and how it was executed bears some interest. Among other provisions, Henderson attempted to arrange for the gradual emancipation of his many slaves, with the option for some to be sent to Liberia. Find more here, and here. [3] O’Connor, 70-71. [4] St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, Girod Street Cemetery, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. At least two Potter’s Fields or indigent burial grounds and unknown family cemeteries were also in the City. [5] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 131-145. [6] Firemen’s Charitable Association, Report of the Committee of the Firemen’s Charitable Association, on the Cypress Grove Cemetery (New Orleans: McKean, 1840), 4. [7] Visitor’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: J. Curtis Waldo Southern Publishing & Advertising House, Nov. 1875), 30-33. This blog post was inspired by the photos within, most of which were taken by Robert W. Kelley of LIFE Magazine in 1957. These images show Girod Street Cemetery in its final moments, as well-dressed adults and children mill around its collapsed tombs and open vaults, with newly-built New Orleans City Hall present in the background of many shots. Mis-labeled “Gerard” Street Cemetery, they offer a vignette of what has long since disappeared from the New Orleans landscape. The full album can be found via Google Cultural Commons here. The topic of Girod Street Cemetery is one that comes up in a few varieties of conversation among New Orleaneans, most often related to the charming notion that the Louisiana Superdome was built atop the burial ground (it wasn’t, per se). The relationship of the old cemetery, known also as the Protestant Cemetery, to the New Orleans Saints football team is one that has been described many times over, best by Richard Campanella and Doc Boudin of Canal Street Chronicles. Check them out to see why you can’t blame the vengeful dead for a losing season. The Protestant Cemetery, 1822 – 1940 The former footprint of the cemetery, however, was indeed quite close to the present-day Superdome. Originally bounded by Liberty, and the former Cypress and Perillat Streets, the cemetery once stood beneath where Superdome parking garages and the Champions Square complex now rise. Founded in 1822, this once-distinctive cemetery lay at the terminus of Girod Street. Previous to that date, non-Catholics were buried in the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. The narrow “Protestants Section” in St. Louis No. 1 was once much longer, but was truncated after construction to Treme Street in 1820. Shortly afterward, Episcopal Christ Church was awarded the land that became Girod Street Cemetery. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Girod Street Cemetery developed into a landscape distinct from its New Orleans cemetery sisters. As the second-oldest cemetery in the city, it amassed the vestiges of early cemetery architecture, from single-vault, stepped-roof structures to more ambitious marble-clad and Classically inspired sarcophagus tombs. The tomb of Angelica Monsanto Dow, who died in 1821, reflected this aesthetic well. Girod Street Cemetery furthermore was an “American” cemetery, in that it became the final resting place for many New Orleans residents who had travelled from elsewhere, particularly the Anglo-American north and Midwest. From these outsiders came tombs and materials inspired by northern cemetery designs – clean, wire-cut Philadelphia brick, liberal use of stone urns and many, many obelisks. Girod Street Cemetery kept within its walls a tableau of cemetery artisanship that stood out from the landscapes of its sister Catholic, municipal, and fraternal cemeteries. Through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, Girod Street Cemetery would become the final resting place for many New Orleaneans of distinction. Heroes of the Mexican American War, civic leaders, and prominent families utilized the burial ground. One estimate suggested that the cemetery was once home to 100 society tombs. For comparison, Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, which is usually noted for its society tombs, has just twenty. In Girod Street Cemetery, the tomb of the New Lusitanos Benevolent Society was likely the most notable. Designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and erected in 1869, the tomb had 100 vaults and a walk-in vestibule framed with a Classical portico. Being somewhat centrally located, Girod Street Cemetery was also heavily utilized as a public burying ground in times of epidemic. It seems as though nearly every major epidemic of the nineteenth century involved a terrible debacle at Girod Street Cemetery, in which bodies were stacked beyond capacity with no one to bury them. This may have also been due to the presence of a de facto Potter’s Field adjoining the cemetery, which was described as early as 1837: “This latter receptacle of the dead [the Protestant cemetery] has for many years been a disgrace to New Orleans. Once the Potters’ Field, it soon became the public burying ground, provided you were able to pay for a vault – otherwise you had to be sent further out into the swamp.”[1] The 1833 cholera epidemic in New Orleans proved especially tragic for Girod Street Cemetery, although it was not necessarily the last time the cemetery fell prey to insufficient manpower in the face of great loss of life: … the unshrouded dead dumped at the gateway of the Girod Street Cemetery accumulated in such numbers that the entrance to its precincts was so obstructed that arriving bodies had to be deposited on the outside; no graves at this time could be dug; no coffins were procurable, for there were neither grave diggers to be had nor undertakers to be found. The City Council was forced to order out the chain gang ‘prisoners’ from the city jails, to dig a trench the whole length of the lower side of the cemetery. It was dug some twelve or fifteen feet wide, and as deep as the filtering water soil would permit, into this receptacle the decomposing bodies were dragged by hooks from the fire companies, without the formality of precedence or order of any kind. As a part of the trench was filled, the earth taken from it was heaped upon the remains of the rich and the poor, the aged and the young.[2] This mass grave would eventually be erroneously referred to as the “yellow fever mound” in later years. In the late 1940s, historians would determine that this feature was in fact the burial of 1833 cholera victims.[3] The Back of the Swamp Girod Street Cemetery, for its stately obelisks and high society residents, would be plagued with issues surrounding its management and topography for most of its existence. In the 1830s, only years into its functional life as a cemetery, it would be noted that its vaults were built with only one brick thickness to their walls, which permitted the “escape of unhealthy odors.”[4] However this was not an issue exclusive to Girod Street – City ordinance did not regulate the quality of tomb construction until the 1850s. What did afflict Girod Street perhaps more than other cemeteries was its location in significantly low-lying land. Girod Street Cemetery swelled with feet of water in Sauve’s Cravasse of 1849, and frequently took on water in other instances, owing to its place on swampy land. In 1880, a special commission of Louisiana state representatives assessed the condition of New Orleans cemeteries and found them all to be in “proper” condition – with the exception of Girod Street Cemetery. Noting, “in the event of rain [Girod Street Cemetery] is always flooded to such an extent that it will affect the sanitary precautions necessary to prevent the contracting or spreading of any diseases,” the commission recommended the cemetery be closed. This recommendation was apparently declined.[5] Girod Street Cemetery’s troubles would not end there. The Fall of Girod Street Cemetery Through the course of its existence, Girod Street Cemetery was owned and operated by Christ Church Cathedral. Until the mid-twentieth century, most religiously-affiliated cemeteries were managed by the respective congregation that owned them. These congregations appointed a sexton or caretaker to manage them by performing burials, building tombs, and keeping records. Although city law required sextons to compile records to be submitted to the Board of Health, the interment records of each cemetery were kept by each sexton to varying degrees of organization. At the turn of the century, increasing industrialization of the monument trade shifted the role of sexton away from groundskeeper and toward that of a sales agent. In some cases, this meant a decline in peripheral duties. This shift is often credited for the lessening of care for the cemetery, as is the inclination of families to move their loved ones remains to newer cemeteries (namely Metairie Cemetery, established 1872). Lack of sellable space and changing racial demographics in the neighborhood of Girod Street Cemetery are also noted as causes for decline. For any combination of these reasons, or others, the administration of Christ Church found themselves in a difficult bind with their cemetery.[6] By the early 1940s, reports on the condition of Girod Street Cemetery appear to have drastically worsened. Wrote one reader in a 1943 letter to the Times-Picayune: … I was horrified to find many of the tombs broken open and others completely destroyed. There was a large fire burning at the top of one of the tombs. I saw what looked like wooden boxes burning. The cemetery looks more like a poultry farm. Atop the tombs are a number of chicken coops, and chickens wandering everywhere, and some of the lovely trees are completely or nearly burned down. Where are the owners of these tombs, that such desecration is allowed? And who cares for this unfortunate burying place?[7]

By the time of this announcement in 1947, Girod Street was merely joining in a much larger phenomenon in which cemetery management was drastically changing. In 1945, the City of New Orleans eliminated the position of sexton from the six municipal cemeteries. In the years following, former sextons and stonecutters would go into business for themselves as cemetery owners, profiting primarily from streamlined materials and low overhead costs. This process was best accomplished by Albert Weiblen, who eventually purchased Metairie Cemetery, and the Stewart family, who built Lake Lawn Park in the 1950s. However, this approach relied on the cemetery having lots available for sale. The last sexton of Girod Street Cemetery, Eugene Watson, died in 1950. In 1948, Christ Church ran multiple notices enjoining tomb owners to repair their property. However, as the cemetery owners pushed to bring the burial ground into the twentieth century, they would stumble over technicalities of property ownership, prohibitive costs, and a booming, modernizing world slowly encroaching on the Girod Street walls. “An Eyesore in the Midst of Progress” The Post-World War II era brought huge changes to nearly every facet of American life. In the cemeteries, everything from materials to business models to the funeral industry transformed. In the American city, revolutionary ideas of urban renewal swept through downtowns, destroying historic districts and erecting aggressively modern new landscapes. In New Orleans this urban renewal took place with mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison, and it took place along Loyola Avenue, where historic buildings were swept away for a new library, city hall, and train depot. The intersection of Liberty and Girod Street, at the boundary of the cemetery, was awkward and could not adequately accommodate recently increased truck traffic volumes. By the late 1940s, even the federal government eyed the Girod Street property as a potential site for a new post office and federal building. In the light of rapidly encroaching superhighways and new urban landscapes, Girod Street Cemetery became even more anachronistic. Perceived as an affront to the bright future of the city’s civic heart, plans to renovate the cemetery fizzled into outright demolition by neglect, aided by the agenda of modern city leaders. Lack of care led to vandalism, which led to inevitable decries that the cemetery was too broken to be fixed. In June 1948, city workers arrived at Girod Street Cemetery and knocked enormous holes in the perimeter wall, hauling away five truckloads of bricks. After protests from Christ Church, Mayor Morrison simply responded that he didn’t realize there would be an objection.[12] In 1954, the City of New Orleans successfully expropriated more than twenty thousand square feet of the cemetery for the purposes of widening Liberty Street. In addition to this seizure of land, city council furthermore requested the mass removal of all remains from the cemetery entirely, and that they be removed to newly-finished Lake Lawn Park, a for-profit venture of the Stewart family.[13] Girod Cemetery is Calling Days after the announcement of the expropriation, city attorneys placed ads in newspaper enjoining any person with family buried in Girod Street to contact the City. Attempt to salvage burials, tombs, sculpture, and any other remaining resource of the cemetery were launched. Many of these reburials had already taken place in years previous by families who suspected the cemetery’s demise. In 1955, the remains, tomb, and monument of Lt. Col. William Wallace Smith Bliss was removed to namesake Fort Bliss in Texas. The Louisiana Landmarks Society led this effort, as it did other efforts to locate families associated with the cemetery. In June of 1955, the city officially purchased the cemetery. In January 1957, it was deconsecrated. Only months later, Louisiana Landmarks member and remarkable cemetery historian Leonard Victor Huber decried the demolition process at the cemetery: “Another 60 days and there will be nothing left of Girod Street cemetery but a memory. Tombs are being broken up… I was in a garden recently with its walls built of marble slabs from the cemetery.[14]” Through the course of demolition, remains of white descent were reinterred at Hope Mausoleum, owned by Leonard V. Huber. African American burials were removed to Providence Memorial Park. In October 1958, Christ Church sold 96,000 remaining square feet of the cemetery to the federal government for nearly $300,000. This sale would transform sections of the cemetery into a parking garage for a planned post office and federal building on Loyola Avenue. Said Frank Schneider of the Times-Picayune, “Girod became an eye sore in the midst of progress but now it will contribute something to New Orleans’ changing skyline. The 14-level post office structure will be the largest federal building in the Deep South.”[15] Learning from Girod Street Although certainly accelerated by ambitions of new urbanism, the issues that led to the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery are the same issues that regularly appear in discussions of historic cemetery management today. The power of the cemetery authority to manage abandoned tombs and lots is a topic of constant contention. Cemetery owning bodies today can write off issues of abandonment by appealing to private property rights, and nearly in the same breath demolish lots that become hazardous or inconvenient to redevelopment. The ability to be conveniently selective regarding Louisiana cemetery law has, in many cases, enabled neglect. This neglect, of course, contributes to cyclical issues of cemetery vandalism, which often goes unabated until conditions are perceived as unsalvageable. The sweeping demolitions that took place across the United States during the 1940s through the 1960s spawned a revitalization of the American historic preservation movement. Iconized by the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in New York in 1963, fatigue over the loss of entire historic districts led to the passing of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 which, among other things, would have likely prevented the Federal government from purchasing portions of Girod Street Cemetery. The tale of Girod Street Cemetery is comprised of much more than a haunted sports arena. For cemetery preservationists in New Orleans, it is a cautionary tale that should never be too far from one’s mind. The stunted successes and disappointing failures could easily revisit any of our burial grounds. [1] “New Orleans Grave Yards,” The Picayune, September 19, 1837, 2.

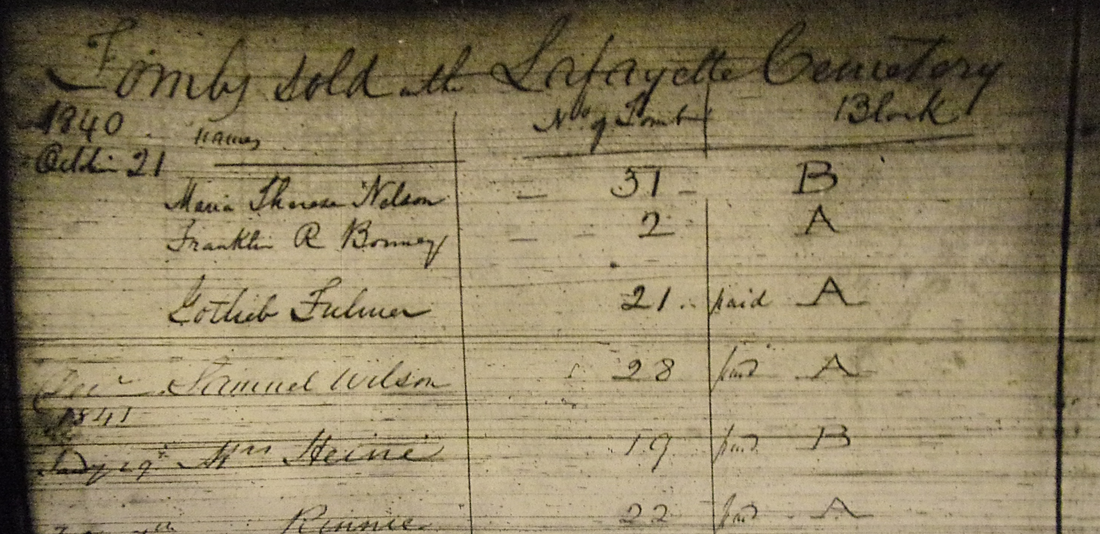

[2] Daily Picayune, August 21, 1885, 2. [3] Leonard Victor Huber and Guy F. Bernard, To Glorious Immortality: The Rise and Fall of Girod Street Cemetery, New Orleans’ First Protestant Cemetery, 1822-1957 (New Orleans: Ablen Books, 1961). [4] “New Orleans Grave Yards,” The Picayune, September 19, 1837, 2. [5] Louisiana State House of Representatives, Official Journal of the Proceedings of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana (New Orleans: The New Orleans Democrat Office, 1880), 285. [6] “The Crumbling World of Girod Cemetery,” Dixie: Times-Picayune States Roto Magazine, August 29, 1954, 6-7. [7] “Historic Cemetery Neglected,” Times-Picayune, June 23, 1945, 10. [8] “Old Cemetery to be Rebuilt,” Times-Picayune, December 21, 1947, 3. [9] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs, Fate of Old Cemetery to Rest with Lot Owners,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945; “Girod Cemetery Inspection Made,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945. [10] “Zulu Chief’s Wish to be Buried with Pomp and Ceremony Fulfilled,” Times-Picayune, August 23, 1948, 24. [11] “Old Cemetery to be Rebuilt,” Times-Picayune, December 21, 1947, 3. [12] “The Crumbling World of Girod Cemetery,” Dixie: Times-Picayune States Roto Magazine, August 29, 1954, 6-7. [13] “Girod Cemetery Strip is Sought,” Times-Picayune, November 12, 1954, 1. [14] “Up and Down the Street: Book on Girod Cemetery Needs Help,” Times-Picayune, August 15, 1957, 19. [15] “Old Burial Spot is Sold as Site for U.S. Garage,” Times Picayune, October 4, 1958, 11. Find your tomb, Research your tomb, Restore your tomb The text below is excerpted from a recent presentation to the 2016 Annual Conference of the Louisiana Historical Association, presented by Emily Ford, MSHP, of Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LL New Orleans cemeteries are so unique that the simple mention of them creates a picture in one’s mind. That picture is likely one of intricate aisles populated by stately, yet crumbling, above-ground tombs; long abandoned, anachronistic cities of the dead which offer up stories through their carved tablets. Traditional histories of New Orleans cemeteries have been static, and ever tied to their place in popular culture. For example, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was founded in 1833 as part of what is now the Garden District. Over the next century, families built above-ground tombs ranging in style from simple masonry structures to grand Classical revival masterpieces. From this foundation, the interpretation of the cemetery usually branches into famous people buried therein, or a focus on specific architectural gems. These interpretations usually rely on a few primary sources. Some cemetery records, selected newspaper articles, and general contemporary observations of the cemetery as it exists in the moment tend to dominate the narrative. What few critical analyses of cemetery architecture exist tend to be repeated through numerous secondary sources. This tends to amplify their subjects as singularly important. For example, the excellent research of Patricia Brady on the stonecutter Florville Foy published in 1993 has been so revisited that the place of Foy among hundreds of other nineteenth century stonecutters appears paramount, as opposed to part of a larger craft community.[1] Beyond the few comprehensive histories relevant to New Orleans cemeteries lie the bulk of what is currently available – histories that focus on cemetery “residents” (for example, Marie Laveau or Colonel Harry T. Hays), high architecture, or the occult. These histories rely on the basic historiographies previously mentioned and typically add curious second-hand stories or rehashed false reports. For example, the translation of the tablet of André Valsin Labarre in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 has been repeated incorrectly for more than a century, but never once has it been noticed that it is located in the wrong lot.[2] Conversely, more dynamic and critical approaches to writing cemetery history will inevitably stumble upon landscapes which dramatically changed as their stakeholders did. For example, the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was not always one of above-ground tombs. The first stakeholders in this cemetery, predominately German and Irish immigrants, found above-ground burial to be perverse, and instead buried below ground. It was not until the 1850s, when their assimilated children gained control of the family lot, that tombs were constructed to emulate the New Orleans ideal.[3] Facts like this not only present a more accurate history of each cemetery, but also accentuate the changing uses each lot would see over time. Sale of lots, demolition of tombs, changes in materials, adaptive reuse, abandonment, and changes in technology are a constant presence in the history of any New Orleans cemetery. Consideration of these details empowers preservationists, stakeholders, and cemetery authorities to more appropriately care for these resources. By shifting the view of cemeteries from that of static landscapes (“outdoor museums”) to one of functional cultural resources, their history and their preservation are dually served. A critical approach to cemetery history combines a multifaceted catalog of primary resources. Original records vary in their condition and availability. With regard to tomb construction, cultures of craft typically focused on the final product and not on drawings, plans, or specifications. In order to piece together the history of a New Orleans cemetery, some creative and rigorous searching is in order. By pairing what primary resources are available with thorough and educated examination of the landscape itself, it is possible to determine the life story of any city of the dead. Original Cemetery Records There are between 32 and 46 historic cemeteries in New Orleans, depending on the criteria employed. Each one is unique in age, architecture, and culture. They also vary in terms of ownership and, thus, quality and location of records. In general, there are four types of cemetery ownership –

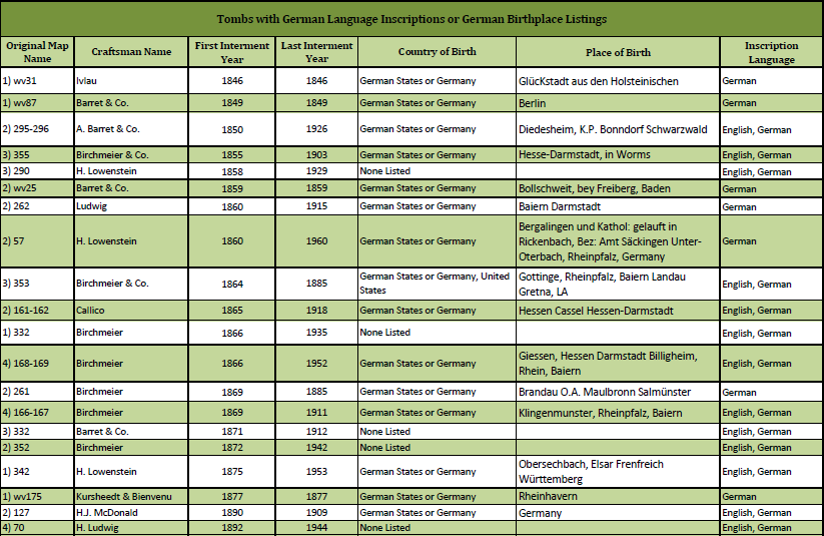

Records of cemetery burials, constructions, demolitions, or demographics were kept by the owning body of each cemetery. Owning bodies vary in their methods of access, preservation, and retention of records. Historic Images What cemetery records cannot contribute to the preservation and documentation of cemeteries is often accessible in a variety of traditional and non-traditional photographic resources. The use of historic photographs in the identification of property and the preservation of individual tombs has not been frequently visited. Furthermore, many photographs which can prove crucial to preservation efforts are difficult to find. When located, however, these photographs can tell the story of an entire cemetery, save a tomb from demolition, or re-unite a family with their property. The photographs of Clarence John Laughlin are an excellent example. Recently digitized by the Historic New Orleans Collection, the photographs date from the 1930s through the 1970s. Laughlin’s prolific hauntings through New Orleans cemeteries prove to be time capsules without compare. Identification of precise location of photographs yields not only histories of specific structures but also entire landscapes. For example, a 1920s postcard showing St. Roch Cemetery and a 1907 photograph of Holt Cemetery show an overwhelming prevalence of wooden markers. Comparison with present-day landscapes indicates enormous changes in the use of cemeteries over time – notably, the industrialization of the monument industry by mid-twentieth century. This shift overwhelmingly transformed cemeteries from highly individualized properties maintained by families to largely mono-stylistic landscapes maintained by cemetery staff – or not maintained at all. As we move into the twenty-first century, the presence of Hollywood in New Orleans cemeteries has created a new type of historiography. Productions like Easy Rider, Love Song for Bobby Long, NCIS, and dozens of others with scenes taking place in New Orleans cemeteries inadvertently document them. Easy Rider is a significant example. Fortunately for historians and preservationists, Peter Fonda’s place in the arms of the statue of “Italia” provides an image taken only years before a heavy-handed “restoration” permanently damaged it. Ephemera and Oral Histories Numerous resources exist beyond photographs and scant cemetery records. These require some amount of supporting evidence, and are best paired with observations of the built environment itself. Some ephemeral records were produced by the purchasers of the tombs themselves. Tomb deeds, once a common part of family papers, are rare, but those that do exist show that many tombs have a chain of title. Such evidence is also present in the notarial archives of tomb builders like Hugh McDonald, Paul Monsseaux, and James Hagan. The full potential of all of these resources is reached when paired with on-site examination of the landscape. This is achieved through painstakingly inspection of tombs for alterations, materials, and inscriptions. Larger-scale data collecting also proves fruitful. For example, while primary resources suggest stonecutter Anthony Barret predominately served a German-speaking market, database compilations of his signed work in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm the breadth of his presence in the German community. These conclusions are additionally supported by oral histories and interviews with the ever-dwindling community of cemetery craftsmen and caretakers, whose potential has rarely been formally tapped. In conclusion, the hidden historical record of New Orleans cemeteries reveals dynamic landscapes that were specific to their community, and constantly shaped by that community. By resurrecting these histories, which highlight stewardship, family involvement, and participation with cemetery authorities, these values can be preserved. Through these means, we can more accurately represent New Orleans heritage and community agency for those who take interest in it and are inheritors of it. Have questions about cemetery interment research or architectural histories of cemetery properties? Contact Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. [1] Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.: Master Marble Cutter and Tomb Builder.” Southern Quarterly 32, no. 2 (Winter 1993): 9-20.

[2] Emily Ford, “André Valsin Labarre: Victime de Son Imprudence,” http://www.oakandlaurel.com/blog/andre-valcin-labarre-victime-de-son-imprudence (January 9, 2016). Based on in situ investigation, Archdiocese records, and 1930s WPA Index (housed at NOPL), this well-known tablet has travelled from Labarre’s actual resting place. [3] “History and Incidents of the Plague in New Orleans,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7 (June-Nov. 1853), 798; Bennet Dowler, Researches upon the necropolis of New Orleans, 22; George Edwin Waring and George Washington Cable, History and Present Condition of New Orleans, Louisiana, and Report on the City of Austin, Texas (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1881), 58; John Frederick Nau, The German People of New Orleans, 1850-1900, 15. Architectural histories within the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 confirm this progression from below-ground burials to above-ground tombs and (eventually) copings. As any narrative on de Pouilly does, this article relies on the groundbreaking research and thesis of Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University thesis, 1992. Which exquisitely analyzed de Pouilly’s work in New Orleans cemeteries. One hundred and forty years ago, on February 21, 1875, Jacques Nicholas Bussiere de Pouilly died in his home on St. Ann Street. In his seventy years of life, de Pouilly had been the harbinger of European neoclassical and revival architecture in New Orleans. We see his touch on our city streets – in St. Augustine Catholic Church, and most notably St. Louis Cathedral. But his influence was arguably greatest in the city’s cemeteries. De Pouilly’s work is present in nearly every viewpoint of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, and much of Cypress Grove Cemetery. The breadth and innovation of his tomb architecture generated uncountable replications and inspirations, the products of which have shaped our burial grounds. J.N.B. de Pouilly was born in July 1804 in Châtel-Censoir, France, southeast of Paris. While much of his early life is unclear, it is assumed that in his architectural training he was influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, if not a student of the school himself.[1] He arrived in New Orleans in 1833, a time in which the French-speaking population of the city hungered for reconnection with Continental styles. He quickly became the architect of note for the city’s First District, designing the St. Louis Exchange Hotel, among many other residential, commercial, and religious projects.

While Père Lachaise and Creole cemeteries like St. Louis may appear stylistically similar, de Pouilly had the significant task of fundamentally shifting the function of his New Orleans tombs from their Parisian prototype. Although the monuments of Père Lachaise appear to be tombs or mausoleums, their design accommodates instead for below-ground burial. That the architect’s designs kept their Parisian aesthetic while having been fundamentally re-worked to allow for above-ground burial is among the more impressive of his professional achievements.[3]