|

Lightning strikes are a lot less rare than you would think - especially in Louisiana. There are few things more effective than forces of nature to remind us how small and vulnerable we can be. In summertime, we remember how much heat and storms can up-end our lives and, in turn, we nurture a healthy respect for wind, water, and sun. But even among these elements, lightning holds a special kind of terror and fascination. It can come seemingly from nowhere, striking indiscriminately, and cut lives and fortunes short in an instant. Today, the chance of being struck by lightning in one’s lifetime are approximately one in 15,300, with an average of 27 people killed by lightning per year in the United States. Over a century ago, in 1858, 59 people were killed by lightning in the US; in 1859, 77.[1] In 1897, 123 people were killed by lightning in the month of July alone.[2] Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (and today), many of these deaths took place in Louisiana, which holds claim as the second most lightning-prone state in the union. (Florida is the first.) In this post, we examine the relationship between humans, cemeteries, and lightning. From scientific discovery to struggles for safety, from tragedy to cemetery artwork, lightning has inspired fascination and fear for as long as humans have been stricken by it.

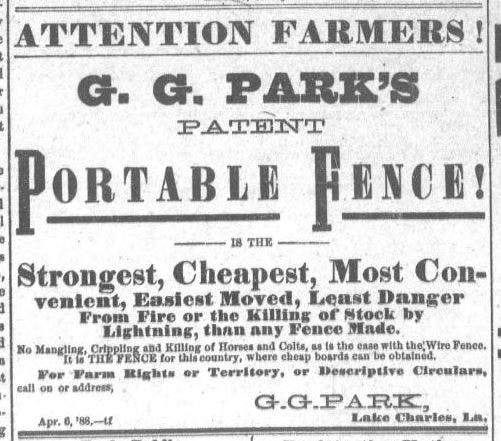

The National Weather Service offers us some insight: no, rubber soles will not help. But often these questions arise from a patently human desire to understand, explain, and control. And in the end, it turns out that lightning just doesn’t work that way. An example: It is rare but not unheard of for a person to be hit by lightning more than once. A common example of this is the true story of Roy Cleveland Sullivan (1912-1983) a Virginia National Park Service ranger who was struck by lightning seven times in his life. The phenomenon is as often true as it is untrue – unbelievable true stories turn to legend and get repeated, altered, and turned into tropes. Later in this article, we will find that Gretna, Louisiana, has its own multiple-strike legend. Statistician David J. Hand in Scientific American tells us that multiple strike incidents are not the result of something special in a person’s physiology. They are simply the result of exponential odds eventually coming up or, “there are so many things in heaven and earth that coincidences become certainties.” Historic Lightning Strikes While being hit by lightning does not make one more likely to be hit by lightning a second time, such superstitions arose from the need to explain this seemingly arbitrary threat. There are, of course, plenty of factors which increase the chance of lightning strikes, and all of them were more likely in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than they are now: open spaces with singular tall trees or structures are the most likely places for lightning to connect. Due to a much more rural, agricultural landscape, stories of strikes were more common in the past.

1863: Union soldier Henry D. Rose of Cincinnati was struck by lightning in Madison Parish, across the river from Vicksburg, Mississippi. He was killed instantly. 1875: J.T. Turaud, an overseer at the property of R.E. Rivers in Plaquemine, was killed by lightning while he sat on horseback in a field. His body was transported back to New Orleans by steamboat and likely buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3.[9] 1878: An African American man was killed by lightning in St. Landry Parish; two other people were also struck in the same instant, including the daughter of Adolphe Donato.[10]

1898: An Ohio-born railroad worker named James M. Griffin died near Annandale, Louisiana, while working on the Kansas City, Watkins and Gulf Railway. He and his fellow workers sought shelter under a tree during a thunderstorm, where he was struck and killed by lightning, burning the left side of his body and melting the change in his pocket.[16] 1900: One African American sharecropper was killed at White Plantation, Lafourche Parish, when lightning hit the porch of a cabin he and others were standing on. Three other men were knocked unconscious but survived.[17] 1900: Cattle rancher and rice plantation owner John W. Taylor was killed by lightning during a storm at a rice plantation on Bayou Barataria. One of the African American workers in the field, named Smith, was struck as well and later hospitalized. Taylor was buried in Hook and Ladder Cemetery in Gretna.[18] 1905: Albert Borque was killed by lightning in Scott, Louisiana, while travelling from Lafayette.[19] 1909: Fred Peterson, an African American man, was killed by lightning while mowing the grass at Myrtle Grove plantation in Plaquemines Parish. His body was taken to the neighboring Saint Sophie plantation for burial.[20] 1911: Fifteen year-old Wesley Fussell was killed by lightning in Washington Parish. He was buried in his family graveyard. 1912: Mrs. Charles Bruno was killed by lightning as she walked along the road outside of Laplace. She was walking with a small child when she was instantly killed by the bolt. The child was unharmed.[21] 1913: Teenagers Alcee Joseph and Walter Joseph (no relation) were struck by lightning when they took refuge beneath a tree on the St. Emma plantation property, where they had been picking moss. After the strike, Walter Joseph ran for help from other workers on the plantation but found Alcee near death upon their return. Alcee died after being brought home.[22] 1917: Beauregard Le Blanc, 58 years old, was killed by lightning while working as an overseer at Arlington Plantation near Luling. His body was brought to Lafourche Parish and buried at St. Charles Borromeo Church cemetery outside of Thibodaux.[23] 1919: Joseph Batts was killed by lightning while working at the skidder of the Opdenweyer-Alcus Lumber Company in Ascension Parish. He was buried at the New River Baptist Church Cemetery near Sorrento.

Today, the National Weather Service warns that deaths by lightning within houses or other structures are still possible. Lightning has the capability to travel through plumbing, electrical, and phone landlines. Historically, lightning deaths in the home seem to relate predominantly to the chimney as a conduit for lightning. Unlike rural strikes which predominantly killed mostly male, often African American workers, the victims of in-home strikes were predominantly women and children. For example: 1846: In Mobile, Alabama, 17 year-old Caroline Goodman was killed when lightning struck the house and traveled through the chimney, passing over two others in the home, and struck her in bed. The bed caught on fire, but the other two people in the house survived.[25] Caroline Goodman was buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile.

1922: Mrs. Sallie Jones (32) and Miss Hazel Guinn (18) were both killed by lightning when Mrs. Jones’ home was struck near Minden, Louisiana.[30] 1934: Mrs. William Cardinale was killed three months after her wedding. She was sitting in the kitchen of her home in Marrero, Louisiana, when lightning traveled through the chimney and struck. She was buried in Our Lady of Prompt Succor Cemetery in Westwego.[31] 1944: Mrs. Bertha Scelson was killed by lightning when her house was struck and the bolt traveled down her stairway bannister. She was buried in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery No. 3 in New Orleans.[32] Urban and Industrial Lightning Deaths Urban and industrial environments brought their own lightning hazards. In Louisiana today, an entire branch of the oil and gas industry is dedicated to lightning protection. Industries like shipping, construction, and heavy equipment all involve factors that attract lightning: tall structures, metal surfaces, and open spaces. Historically, lightning has caused some great tragedies in Louisiana industrial spaces: 1856: A blacksmith named Henry Tisserand was killed by lightning in his workshop near Jackson Barracks in New Orleans. The report states that he was struck to the ground, then “sprang up and called for a drink of water. It was offered to him, but he was unable to drink it, and the next instant fell dead on the floor.[33]” 1859: Irish-born Jerry Brian was working at the livestock landing near Jackson Barracks when a storm drove him to a nearby building. The building was struck and Brian was killed. 1920: In arguably the most tragic lightning incident in New Orleans history, eight men were killed during the construction of the Industrial Canal. The men were working on the canal’s construction (which was completed the next year) in a section between Japonica Street and Claiborne Avenue. The men had taken shelter from a storm on the second level of a pile-driver when a lightning bolt struck one of the driver’s cables. The bolt traveled across the steel cable which ran under the men’s feet, killing seven instantly. The foreman, Edgar Philips, 48 years old, later died at Charity Hospital.[34] In addition to Philips, who was buried in St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1, the victims were:

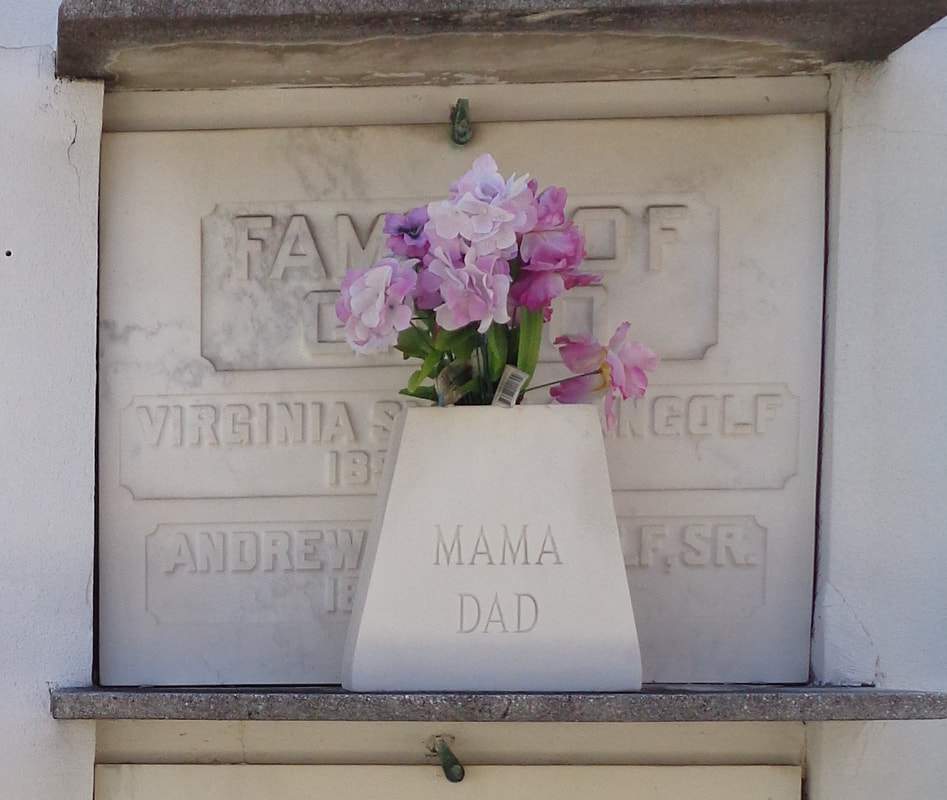

Newspapers reported that most of the men were members of the Piledrivers Union, and some were members of the Iron Workers Hall and American Federation of Labor (AFL). Noonan was a member of the United American Mechanics of Louisiana. These organizations contributed hundreds in aid to the men’s families, and hundreds of members attended their funerals.[35] Funeral expenses were paid by the Dock Board. Lightning in New Orleans Cemeteries Without a doubt, lightning has put its share of people in cemeteries. Over the years in Louisiana, however, it has also had its own impact on the cemeteries themselves. No better example of this phenomenon is the bizarre story of John W. Taylor’s tomb in Gretna’s Hook and Ladder Cemetery. As noted above, Taylor died in July 1900 after being struck by lightning at his Bayou Barataria rice plantation. His funeral was noted as well-attended by the townspeople of Gretna, and he was laid to rest in a family tomb. From here, legend has it that Taylor’s lightning problems gained a whole new dimension. In 1956, the Times-Picayune printed a story that seemed too bizarre to believe: That Taylor’s tomb had been continually struck by lightning since his burial in 1900. Said the story, “… his tomb was struck by lightning again and again so that the custodians of the cemetery finally collected the splintered bones and buried them in an unmarked grave.[36]” It seems the newspaper made some efforts to confirm this story, speaking to “Louis ‘Ben’ Gehring of 536 Huey P. Long Ave, Gretna, [who was] now in his 80s and the oldest living member of the Hook and Ladder Society, which maintains the cemetery, [he recalled] that lightning struck the tomb on two different occasions until the custodians were forced to bury the bones elsewhere.[37]” While it still seems improbable – especially since lightning strikes in cemeteries can be the stuff of urban legend – one more source confirms the tale of Taylor’s tomb. Less than a year after Taylor’s death, a severe storm blew through Gretna. Lightning struck the David Crockett Fire Company No. 1 fire house, nearly causing a fire. Farther down Lafayette Street, lightning struck two tombs in Hook and Ladder Cemetery – it struck the society tomb of Gretna Hook and Ladder Fire Company… and it struck the tomb of John W. Taylor. Said the Picayune: “The bolt knocked half a dozen bricks from the top of the vault in which Mr. Taylor’s body reposes, and left a huge black mark on the face of the vault.[38] In the Garden District of New Orleans, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 has its own tales of lightning. In 1856, carriage driver John Burke was struck by lightning outside the gates of the cemetery. His horse bolted down Washington Avenue and fell near Carondelet Street, where Burke’s body was recovered.[39] It is unclear where Burke was interred. Three years later, the body of Andrew Quirk was buried in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. His tablet is the only one in that cemetery to specify that he was “killed by lightning.[40]”

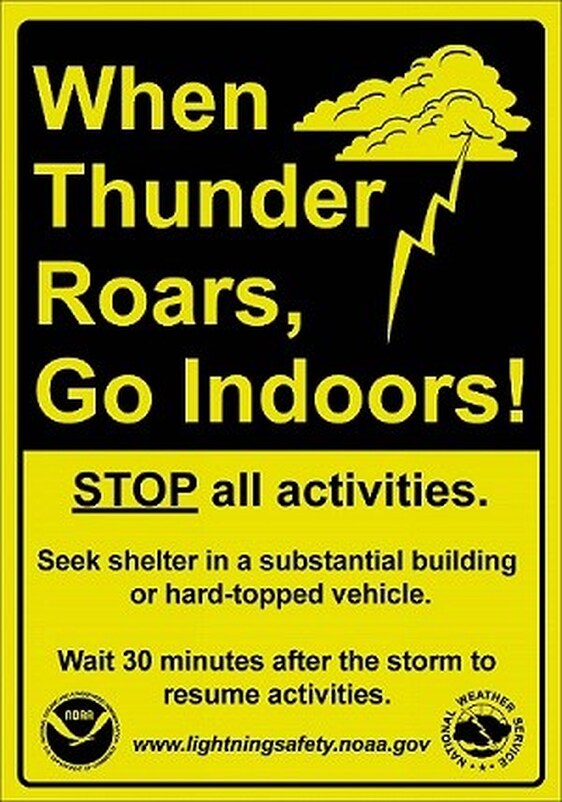

On June 16 of this year, 59 year-old Charles Jackson was struck by lightning while working on his mother’s roof in Africatown, near Mobile, Alabama. He passed away in early July. In a news report, his sister stated that she hoped his death could raise awareness of the dangers of lightning. (The family has a GoFundMe campaign to repair the roof. We ask our friends to consider donating.) Fortunately, there are resources to stay educated and keep our families safe. The National Weather Service makes it simple: When thunder roars, go indoors. And wait thirty minutes until the thunder has passed until going back outdoors. Lightning can travel miles behind a storm after it has passed. For more information, check out the National Weather Service information pages below: [1] “Statistics of Lightning,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, June 20, 1860, 1.

[2] “Don’t Fear Lightning,” Lafayette Gazette, October 27, 1900. [3] “Death by Lightning,” Baton Rouge Gazette, August 3, 1844, 2. [4] “Accidents from Lightening,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, May 31, 1849, 2. [5] “Killed by Lightning,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, July 22, 1851, 2. [6] Baton Rouge Daily Comet, June 24, 1853, 2. [7] “Killed by Lightning,” Southern Sentinel (Plaquemine, Iberville Parish), May 3, 1856, 2. [8] “Death by Lightning,” Harrisonburg Independent, April 14, 1858, 2. [9] “Letter from Plaquemine: Crop Prospects – An Overseer Killed by Lightning,” New Orleans Bulletin, May 21, 1875, 2; “Brought to the City,” New Orleans Bulletin, May 20, 1875, 8. [10] “St. Landry Courier,” Donaldsonville Chief, June 15, 1878, 4. [11] Louisiana Capitolan, June 26, 1880, 4. [12] “Killed by Lightning,” St. Charles Echo, August 6, 1881, 1. [13] St. Landry Democrat, August 29, 1885, 2. [14] Lafayette Gazzette, July 14, 1894, 3. [15] Houma Courier, April 17, 1897, 5. [16] “Killed by Lightning,” Bayou Sara True Democrat, June 25, 1898, 8. [17] “Killed by Lightning,” Weekly Thibodaux Sentinel, June 23, 1900, 1. [18] “A Fatal Stroke: Lightning Kills John W. Taylor on his Barataria Plantation,” Times Picayune, July 11, 1900, 3. [19] “Killed by Lightning,” Lafayette Advertiser, March 22, 1905, 4. [20] “Killed by Lightning,” Lower Coast Gazette (Point a la Hache), June 5, 1909, 2. [21] “Woman Killed by Lightning,” Caldwell Watchman (Columbia, Louisiana), September 27, 1912, 1. [22] “Negro Killed by Lightning,” Donaldsonville Chief, May 10, 1913, 5. [23] “Victim of Lightning Bolt,” Times-Picayune, July 15, 1917, 75. [24] “Effects of Lightning,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, August 1, 1851, 3; “A Dead Horse,” New Orleans Bulletin, July 9, 1874, 3. [25] “Don’t Fear Lightning,” Lafayette Gazette, October 27, 1900, 3. [25] “Meloncholy Death,” Baton Rouge Gazette, February 28, 1846, 1. [26] “Death by Lightning,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, August 13, 1849, 2. [27] The Meridional (Abbeville, Louisiana), June 30, 1900, 2. [28] “Lightning Kills Two Persons,” Lower Coast Gazette, March 5, 1910, 1. [29] “Children Killed by Lightning,” Weekly Iberian, July 1, 1922, 3. [30] “Lightning Kills Two Women,” Vernon Parish Democrat, March 23, 1922, 6. [31] “Lightning Victim’s Rites on Thursday,” Times Picayune, August 22, 1934, 2. [32] “Lightning Kills Former Resident,” Times Picayune, April 20, 1944, 3. [33] “Death by Lightning,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, June 21, 1856, 2. [34] “Eight Killed by Lightning in New Orleans,” Franklinton Era-Leader, July 15, 1920; “Bolt Kills 7 Canal Workers, 3 Hurt,” Times-Picayune, July 9, 1920, The death toll would rise to 8 after the death of foreman Edward Philips at Charity Hospital; “Families of Flash Dead to be Aided: Unions and Dock Board Will Assist Kin of Eight Lightning Victims,” Times Picayune, July 10, 1920, 6; [35] “Funeral Notice,” Times Picayune, July 11, 1920, 4; “Victims of Bolt Are Laid to Rest,” Times Picayune, July 11, 1920, 13. [36] “Lightning Followed Him After Death,” Times Picayune, March 25, 1956, 145. [37] Ibid. [38] Times Picayune, August 9, 1901, 6. [39] “Coroner’s Inquests,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, July 7, 1856, 3. [40] “The City,” Times Picayune, June 9, 1859, 1. [41] “Lightning Rips Open 19th Century tombs in N.O. Cemetery,” Times Picayune, August 7, 1990, 19.

4 Comments

5/20/2020 04:26:17 am

This post actually made my day. You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks

Reply

7/18/2021 06:53:25 pm

The story of a Bruno struck by lightning was true, but I thought it was Mary Bruno- DOB-1905 DOD- 15 Oct 1937. Her father was James Bruno. My Great Grandfather was Charles Bruno I think his wife's name was Mary Matzuia which may have been Mrs. Charles Bruno. can you please tell me where you found this information? Thank You.

Reply

Emily Ford

8/5/2021 07:02:48 pm

Hi Sydney, this was sourced from an article from the Caldwell Watchman out of Columbia, Louisiana on September 27, 1912. The article read:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly