|

First in a five-part series of All Saints' Day through New Orleans history New Orleans heritage is steeped in holidays and celebrations. Amidst the hedonism and mystic antics of Mardi Gras, Twelfth Night, and other festivals is the contrasting solemnity of All Saints’ Day. Part of the Catholic calendar since the fifth century, All Saints’ Day (also known as the Feast of All Saints, Hallowmas, and All Hallows) has its origins in Roman, Germanic, and Celtic celebrations seated in prehistory. Today it is celebrated on November 1, although some Eastern Orthodox and Protestant denominations celebrate it on the first Sunday of November. The feast day began as a holy day in which the lives of the Catholic Saints were remembered and honored. However by the time of the arrival of French and Spanish colonists to New Orleans, the day rather signified the recognition of all saints, “known and unknown,” and more generally the remembrance and communal mourning of the dead by their survivors. By 1853, the oldest above-ground cemetery in New Orleans (St. Louis Cemetery No. 1) was 65 years old, and the imported traditions of above-ground burial and observance of All Saints’s Day enjoyed great significance in the rituals of the Catholic and Protestant communities. From the Catholic St. Louis Cemeteries to Protestant Girod Street, municipal Lafayette, and fraternal Cypress Grove and Odd Fellows’ Rest, the day was observed and reported on – not only as a day of mourning, but one of cultural spectacle, high style, and great charitable expectations.

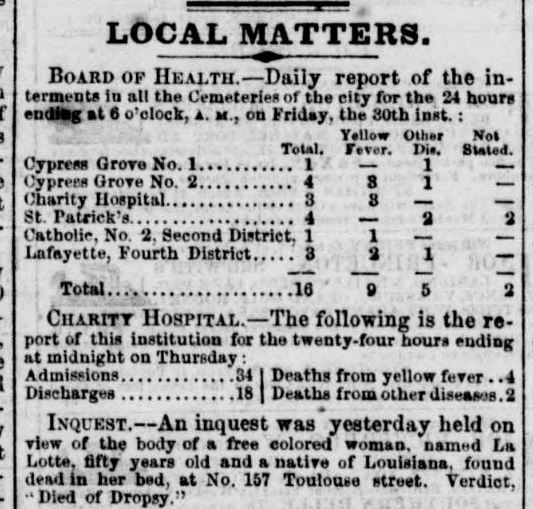

From the numerous complaints made this morning of the careless manner in which the coffins containing dead bodies are left at the Fourth District cemeteries, it would appear that there are not enough hands employed there to bury the dead. The hearses bringing them place the coffins at the gate of the cemetery, and there, it is stated, numbers of them remain for hours, and in some cases all day and all night, the effluvia given forth reaching houses four and five squares off. … it is a sad enough necessity that we should live in the midst of an unsparing epidemic… But it should be the last reproach a city should receive, that she cannot bury her dead decently and respectably, in accordance with the feelings in which every human being participates.

The devastation of the epidemic lay not only in the cemeteries, but ever more so in the homes for widows and orphans. Benevolent associations, the members of which were bonded by nationality, profession, or religion, incorporated into All Saints’ Day a tradition of charity in which the orphans of various asylums would be present in the cemetery, collecting alms to support their care. Among these asylums was that of the Catholic orphan boys of the Third District, which cared for 300 children in October of 1853, and predicted another 100 within the next month. This institution, among others, stood present at the Catholic cemeteries on November 1, hoping for enough donations to build a new wing to accommodate their new charges.

The Daily Crescent describes a day of crowded cemetery avenues and people of all ages, “singularities of every hue, and representing every nationality… not before midnight were the decorations complete. It was then that thousand tapers and waxen lights everywhere covering the tombs were lit up, and a light flashed over the scene, imparting to it an almost magical brilliancy.” Said one author to the editors of the Baton Rouge Daily Comet of New Orleans’ All Saints’ Day observance: "Now, however, I am so much of a Catholic that I like all Saints day [sic] – I am in favor of the custom of making an annual pilgrimage to the graves of those we loved in life…” this author, signed only as “L,” describes the throngs of people, the “gaudy” decorations, the invocations of beautiful hymns. Yet the pall of epidemic’s devastation burns through even the most endearing recollections of All Saints’ Day 1853. “L.” concludes his letter not with the solemnity of honoring the dead, but with the discussion of the recent suicide of a New Orleans lawyer: He was buried on Sunday [October 30] followed to the grave by a large number of citizens. While the long cortege of carriages which followed his remains were passing slowly down the street to the Protestant Cemetery, another funeral came dashing along Hevia Street [now Lafayette Street], followed by a half dozen empty carriages, and all driven at a smart trot, as if in a hurry to get the dead out of sight as soon as possible. The latter procession had just time to cross the path of the former ere it came up making a forcible contrast in appearance and character between the two. One was a rich man going to lay down in his last resting place, the other was a poor stranger hurried to his final bed. When earth has reclaimed what was of her, who will be able to distinguish the ashes of the one from the other? Sources:

Walter Farquhar Hook, A Church Dictionary (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1852), 16. “Burying the Dead,” Daily Picayune, August 8, 1853, 1. “Female Orphan Asylum,” Daily Picayune, October 23, 1853, 2. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 28, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, October 31, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1853, 1. “All Saints’ Day,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, November 2, 1853, 1. “Correspondences,” Baton Rouge Weekly Comet, November 6, 1853, 1.

2 Comments

9/30/2017 12:49:26 am

Wow! The ending to this story is so beautiful. It talks about how people are all equal regardless of our possessions. When we die, we will all go back to how we started. We will all turn into ashes and when we do, no one will be able to recognize which person is which. That is the lesson in life that we must carry with us every day. Life is too short to compete with other people. Do not try to make others feel that you are superior than them because only God is superior over people.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly