|

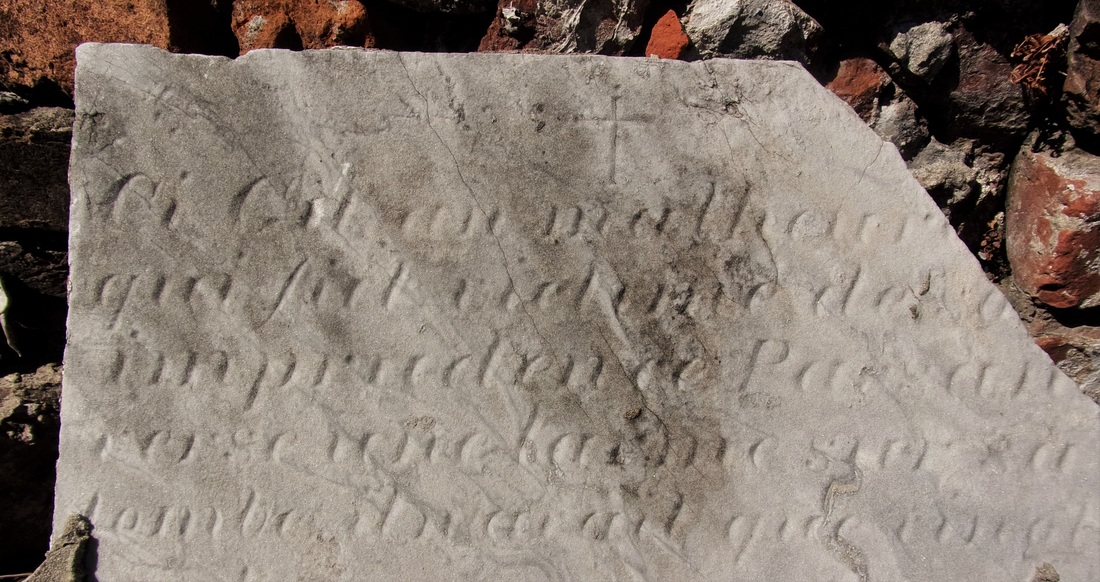

Special thanks to Mary Lacoste, author of Death Embraced, for drawing our attention and curiosity to Mr. Labarre. On any given day in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, hundreds of people walk down a back alley toward the “Musicians’ Tomb.” Led by tour guides, they may stop at a newly constructed-tomb or point out a newly-restored one. A few point out the tablet of André Valcin Labarre. One tour guide points to the loose-lying, grey-veined little tablet and states, “He was a bad boy,” as they walk past. The tablet is leaned up against a structure that has likely not been tended for nearly two hundred years. Half-collapsed, it is hardly a tomb any longer. Like uncountable burials in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, it is on its way to becoming completely erased. But Labarre’s tablet remains. Now broken and missing a piece, the Labarre tablet has long been referred to as among the most interesting in the cemetery. Its French inscription is difficult to read, let alone translate, but the words “victime de imprudence” remain visible. These three words have made the tablet a sensation, although nearly all accounts of its message have been incorrect. In a way, this is a story of a man who died young and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. But if this was all there was for André Valsin Labarre we wouldn’t be intrigued by him today. Instead, this is also a story of how one man’s epitaph led to a century of confused transcriptons, translations, and misunderstandings. In the nearly two centuries since his death, he continues to sow imprudence.

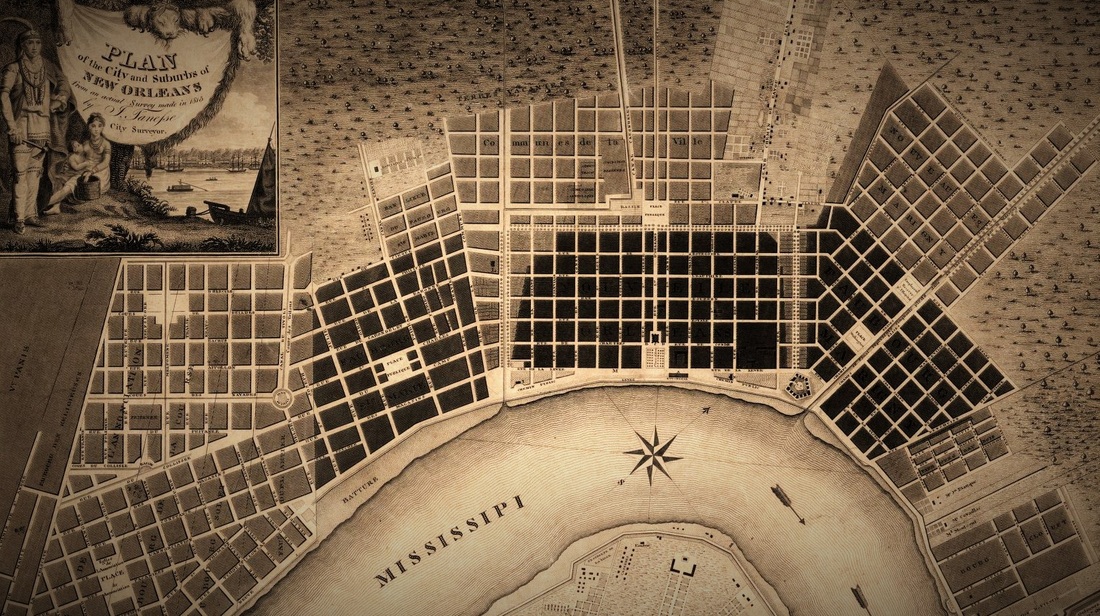

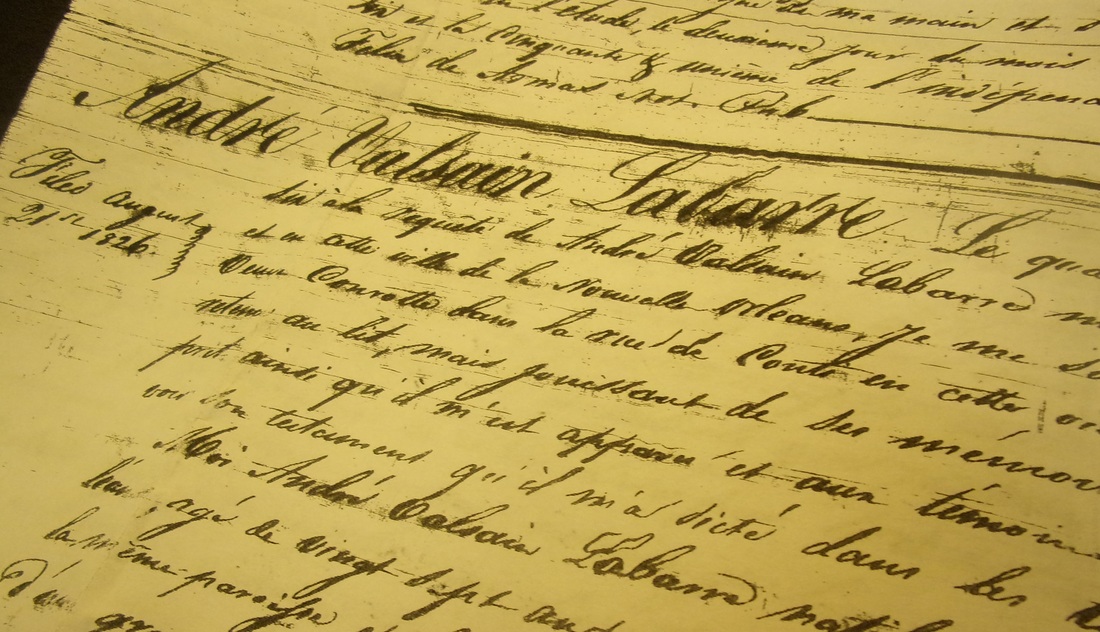

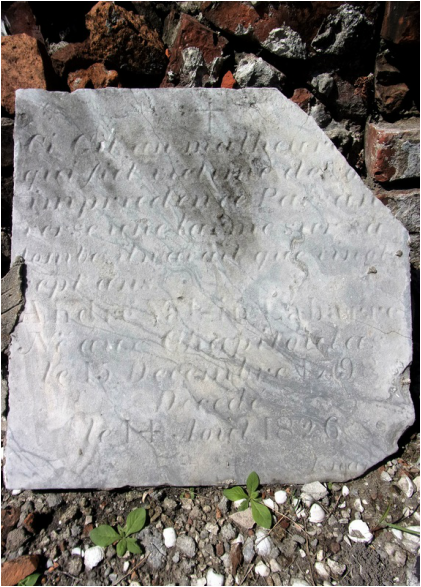

From the mid-1700s, the Labarre family owned significant holdings of land in what would become Jefferson Parish. Beginning with Francois Pascalis de Labarre Sr., who served law enforcement and municipal roles, a number of Labarre men claimed the post of sheriff in Jefferson’s early days.[2] Biographers and genealogists refer to the Labarre family as tied to their land, known as Chapitoulas Plantation or the Chapitoulas Coast.[3] The property line for this plantation is still demarked as Labarre Road in Jefferson. The family’s ancestral home, White Hall, is now home to the Magnolia School. André Valsin Labarre (usually addressed as simply Valsin) was born on December 15, 1798 at Chapitoulas Plantation. He is described as having less attachment to the plantation homestead than his parents, siblings, and cousins. According to one genealogist, Valsin was “the first of the Labarre family to move back to the city” of New Orleans since Franscois Pascalis Sr. purchased the Chapitoulas plantation in 1750.[4] Labarre lived in the Faubourg Marigny in 1822, when he married Virginie Conrotte (c. 1808-1850). The two had only one child, Samuel Placide Labarre, born December 4, 1822.[5] As for what André Valsin Labarre could have possibly done to deserve a tablet that suggests he died of his own imprudence, there is no clear answer. As we will see with later interpretations of his tablet, much is up for conjecture. His will shows a fondness for fine possessions: a “big horse of superior quality,” Spanish saddles and riding gear, a double-barreled hunting gun. He also owned five slaves: Fortune (30 years old), Thom (28), Constant (18), Maria (19), and Eliza (15). Thom and Fortune were “carters,” leading some to assume they “operated a cart and sold goods for their master.[6]” Beyond this means of income, it appears Valsin held no definite occupation, suggesting he may have been a man of leisure who enjoyed fine guns and horses.[7] On July 14, 1826, notary Carlile Pollock visited twenty seven year-old André Valsin Labarre at a home on Conti Street, likely the home of a relative.[8] Pollack was called to the house by Virginie Conrotte. Wrote Pollack: on j'ai trouvé le requerant malade retenir au lit, mais jouissant de memoire et entendement naturels, et bien d'esprit “there I found the sick man confined to his bed, but sound of memory and understanding, and in good spirits.” Pollock had been called to compose the last will and testament of André Valsin Labarre. In this will, Labarre named his oldest brother, Francois Pascalis Labarre II, executor and beneficiary of his property. He also requested that his brother care for his widow and son, Samuel Placide Labarre, and see that his son completed proper schooling.[9] No record documents exactly what had caused his illness. Valsin died on Monday, August 14, 1826, one month after writing his will. His obituary in La Courier de Louisiane only confounds the possible cause of his death, but describes him fondly: Mr. Valcin Labarre est décédé Lundi soir, à l'age de 27 ans, a la suite d'une longue et cruelle maladie. Doué d'une excellence constitution et a fleur de l'age, il semblant devoir fournir une longe carriere dans cette vies mais une entiere negligence de lui-meme a donné prise a la fatale maladie qui l'enleva a une nombreuse et respectable famille, a une interessant et jeune espouse, et un enfant en bas age. Mr. L. avait d'excellentes qualites qui le font regretter d'un nombreux cercle d'amis. “Mr. Valcin Labarre died Monday night at the age of 27, following a long and cruel illness. Endowed with an excellent constitution and in the flower of his age, it seemed he should have had a long career in his life, but a complete negligence of himself gave rise to a fatal sickness which swept him away from a large and respectable family, young and caring wife and a small child. Mr. L’s brilliant qualities will be missed by a large circle of friends.”[10] The Epitaph This sense of wasted potential is echoed in the poignant tablet his family erected at his grave. After close study of the tablet, as well as all past transcriptions of it, this is the epitaph carved for André Valsin Labarre:  Ci Gît un malhereux qui fut victime de son imprudence. Passant, verse une larme sur sa tombe, il n’avant que vingt sept ans. André Valsin Labarre Né aux Chapitoulas le 15 Decembre 1798 Decedé le 14 Aout 1826 Here lies an unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Passerby, shed a tear upon his grave, he was only twenty seven years old. André Valsin Labarre Born at Chapitoulas December 15, 1798 Died August 14, 1826 Labarre’s tablet was carved by Jean Jacques Isnard from gray marble. Isnard (1779-1859) was one of the earliest stonecutters in New Orleans. His prolific work can be found throughout St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Valsin’s death and burial in 1826 was the end of a short, but presumably happy life. His cause of death will likely remain a mystery. “Indiscretion or Excess” The phrase “victim of one’s own imprudence,” appears in rather specific narratives in the nineteenth century. It suggests a negligence of self-care by way of excessive living or failure to treat illness in its preliminary stages. For example, a woman who dies of consumption because she did not treat a cold was a victim of her own imprudence. Alternatively, the term “victim of imprudence” was frequently used in advertisements for men who had contracted venereal disease. In the case of Labarre, others have suggested perhaps the excesses of drink, although no record can confirm. For whatever reason, Valsin’s family requested such language for his tablet. Little would they know that the words they paid Isnard to carve would become somewhat of a legend a century later. A Travelling Tablet Perhaps the greatest mystery of all, however, is where Valsin himself was originally buried. A survey completed in the 1930s notes the tablet to be located in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, Aisle 8-R, although it does not specify lot number. Today, Valsin’s tablet is located in Aisle 7-R. Unfortunately, the original cemetery records for 1826 do not specify lot number. While we may love Valsin’s immortal eulogy, his mortal remains may never be located for sure. One Hundred Years of Mistranslation Nearly 75 years after Valsin’s death, in 1900, the New Orleans Daily Picayune wrote a full-page piece on local cemeteries in honor of All Saints’ Day, November 1. This was a common annual occurrence in which newspapers would describe the scene at each cemetery, noting curious epitaphs or beautiful new tombs. With this article, Valsin’s memory was revived in a very peculiar way: On one old slab, almost defaced with age, is the inscription “Ci git un malhereuse qui fut victim de son imprudence. Verse un larme sur sa tombe, et un ‘De Profundis’ s’il vout plait,” por son ame. Il n’avait que 27 ans, 1798.” The translation reads: “Here lies a poor unfortunate who was a victim of his own imprudence. Drop a tear on his tomb and say if you please the Psalm, ‘Out of the Depths I Have Cried unto Thee, Oh, Lord’ for his soul. He was only 27 years old.[11] Three years later, on November 2, 1903, the Picayune printed the exact same paragraph in another All Saints’ Day article. This printing birthed two widely-repeated falsehoods regarding Labarre – that he had died in 1798 (the year he was born), and that the tablet had an additional line regarding a psalm, which it clearly does not. This misunderstanding would perpetuate itself, making scholars and authors truly the victims of their own imprudence. In 1919, a tourist brochure said of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1: “The inscriptions are in French, and many of them tell how he who sleeps beneath ‘fell in a duel, the victim of his own imprudence.[12]’” It is unclear if this is directly inspired by Labarre or perhaps another now-missing tablet. Unfortunately, even the most revered of New Orleans cemetery texts replicate to the Labarre myth. In one seminal 1974 book, the authors suggest again that Labarre’s is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, quoting the Picayune article. The text also muses that perhaps the poor fellow had died in a duel. From 1974 to 2004, three other publications cite this faulty article, each suggesting that it is the oldest tablet in the cemetery, and that the deceased had met his end in a duel. One insists that the tablet is long lost to history. All this time, André Valsin Labarre’s tablet has sit idly by as tour groups wind in and out of the cemetery aisles.

New Orleans cemeteries typically identify the owners of tombs by direct lineage. Through this lens, there are no descendants to claim care of the prodigal son’s tablet. Valsin’s son, Samuel Placide Labarre, married Emma Labranche in 1866. Their union produced one son, who Samuel named after his father, Valsin. Valsin Labarre died around 1890. There is no indication that he married or had children. Additionally, Virginia Conrotte remarried after Valsin’s death. She and her new husband, Daniel Gregoire Borduzat had at least four children. Unfortunately, the surname Borduzat appears nowhere in indexed cemetery records. If indirect relatives to Valsin Labarre remain, they have not reconnected with his burial place. Both the tablet to his memory and Valsin himself have become, in a sense, immortal for the most peculiar of reasons. Yet their fate remains suspended between the aisles of New Orleans' oldest cemetery, awaiting the next chapter in their story. [1] Stanley C. Arthur and George Campbell Huchet de Kernion, Old Families of Louisiana (New Orleans: Harmanson, 131), 98-104.

[2] Arthur and Campbell, 98. [3] William Reeves, De La Barre: Life of a French Creole Family in Louisiana (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1980), 79, 88. [4] Reeves, 88. [5] Reeves, 175. [6] Reeves, 119. [7] Probate inventory of André Valsin Labarre, New Orleans Public Library microfilm KR 308, Old Inventories, Vol. L, 1821-1832. [8] 1821 New Orleans directory, Louis Labarre, No. 14 Conti. [9] New Orleans will documents, New Orleans Public Library, VRD410, 1805-1833, Recorder of Wills, Vol. 4, 106. [10] La Courier de Louisiane, August 16, 1826, 2. Accessed via microfilm, New Orleans Public Library. Translation composite of a number of translations from French speakers, William Reeves, and Emily Ford. [11] “All Saints Day,” Daily Picayune, November 2, 1900, 3. [12] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “In Old New Orleans,” from Travel, Vol. XXXII, No. 4 (Feb. 1919), 26.

2 Comments

Nicole Miller

1/25/2016 12:32:35 pm

So well researched and written! I can tell you were almost obsessed with this one. Thanks for sharing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly