|

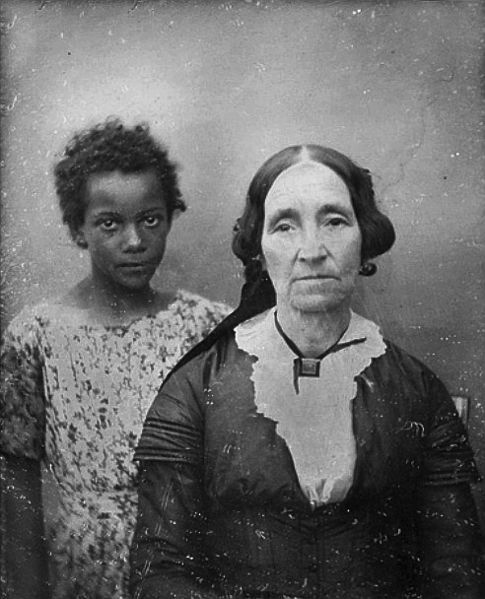

Above: Ceramic portrait and brass cover, Hook and Ladder Cemetery, Gretna, Louisiana. The art of the photograph transferred to ceramic belies a hidden history in New Orleans cemeteries. In more typical (belowground) cemeteries throughout the United States, photo ceramic portraits are often the most remarkable feature of the landscape. Here in the Crescent City, they are fewer in number and often outshined by monumental architecture. Yet in the midst of curious tombs, grand Continental designs, and stories of intrigue, they remain: Small, uniformly-sized, concave ceramic disks onto which timeless photographs of the deceased have been fired. Happy couples, glamorous ladies, innocent children, all immortalized on their tablets and headstones. Perhaps even more so than memorial sculpture, porcelain photographs connect the cemetery visitor with the cemetery resident, gazing out from the realm of years passed.

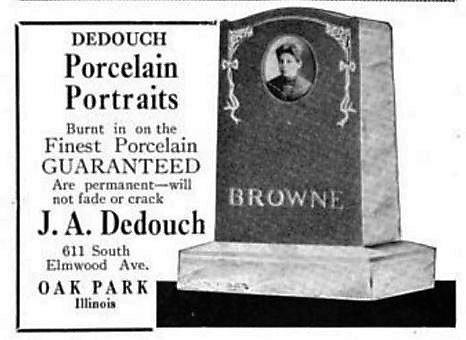

Bulot and Cattin’s process was only the first iteration of a “transferotype” or transferal processes of original images to hard surfaces. Most involved the same basic method in which the original image was duplicated via the collodion process, the collodion layer was then soaked until it separated from its glass plate, and slipped over the ceramic disk. After this preparation, the ceramic was fired in a kiln until it was fixed. After firing, the final product was often brushed with enamel. Myriad modes of image transferal were patented and modified by various nineteenth century inventors, including Alphonse Louis Poitevin, Mathieu Deroche, and Lafond de Camarsac (who won a gold medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition for his process). The intricacies of each process are not necessary for this story, but are exquisitely explained by the Dutch Enamelists Society (Vereniging van Nederlandse Emailleurs) here: History of Enamel Photography Photo Porcelain in the United States In both the United States and in Continental Europe, the use of photo porcelain on memorials and monuments became popular among Southern and Eastern Europeans. In Italy in particular, it is said to have become widespread. Evidence or literature to support why photo porcelain was more desirable among these communities is scant. In the United States, most sources suggest that photo porcelain was a way for immigrants to maintain connections to family and culture in a strange land.[3] Prior to the 1890s, portraits were obtained by families through retailers (often photographers) who ordered their wares from specialists in Europe. This changed in 1893 when Joseph Albert Dedouch established his own patents and company in Chicago, Illinois. Dedouch’s company produced a vast number of porcelain photographs. Dedouch was so successful that his products were given a new name – “Dedos.” Over time, the finer aspects of the art developed – the addition of chromatic tints to color the photograph, and manual editing of images to improve overall appearance.

Ceramic portraits in Savannah Cemeteries like Laurel Grove and Bonaventure display many of the same issues these artifacts face throughout the country. Chips, impact marks, and theft are common. Ceramic Portraits in New Orleans The tradition of ceramic portraits in New Orleans, however, appears to have caught on much later. From 1910 to 1930, other trends such as Georgia marble, tree-trunk monuments, and advances in stonecutting technology appear contemporary with the rest of the country. Conversely, nearly all photo porcelain dates from the 1950s onward. Even from this period to the present, ceramic portraits are rare. There are a number of reasons why this may have been the case. Photographers and monument companies, who would have typically brokered the sale of ceramic portraits, may have simply chosen not to tap into this market until much later. It is possible, as well, that the process of constructing, purchasing, and maintaining above-ground tombs seemed incongruous with the installation of these artifacts. What is evident from the presence and location of these portrait is that, like the rest of the country, they remained popular among Italian immigrants and Americans of Italian descent. Perhaps the only cemetery in which ceramic portraits are commonly visible is St. Roch Cemetery No. 2, in which the New Orleans Italian community has a distinct presence. Above: Photo porcelain portraits from St. Roch Cemetery No. 2, dating from the 1950s through the 1980s. (Photographs by Emily Ford)

As for the famous “Dedos,” the Dedouch company survived the twentieth century intact and was sold in 2004 to Canadian company PSM. The Canadian company still sells the “Dedo Classic,” although these portraits are pigmented by precision machinery, whereas the original Dedouch portraits were hand-painted for more than a century. Preserving photo-ceramic portraits is a multi-faceted and nuanced task. It must require aspects of documentation, materials conservation, and skilled artisanship. For by preserving the antique processes by which these portraits were made, their cultural heritage as a whole is safeguarded for future generations. Of course, it is impossible to protect resources that have never been defined. In New Orleans, no comprehensive attempt has ever been made to catalog instances of photo porcelain in cemeteries. If they are to be preserved for the future, and protected from vandalism or theft, documentation is essential. In a world in which images have become ubiquitous yet ephemeral, photo-ceramic memorial portraits offer a connection to the most deeply personal and sentimental aspects of memorial art. The opposite of ephemeral, their tangibility and endurance create in our cemetery landscapes a memory almost even more real than the people they memorialize. [1] Johann Willsberger, The History of Photography: Cameras, Pictures, Photographers (Doubleday: 1977), 145; “Photographic Correspondence,” from Notes and Queries: Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc. Vol 12, July-Dec, 1855, 212.

[2] Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, Volume 2 (London: George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1869), 66. [3] Ronald William Horne, Forgotten Faces: A Window into Our Immigrant Past (San Francisco: Personal Genesis Publishing, 2004). This publication may be the only book specifically dedicated to photo porcelain, although it focuses almost entirely on the cemeteries of Colma, California. Marilyn Yalom, The American Resting Place: 400 Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 20-21. [4] Maison Blanche advertisement, Times-Picayune, March 30, 1932, 26; Sears Roebuck prices from The American Resting Place, 20.

2 Comments

Eddy Gonzalez

1/25/2020 06:51:09 am

I have a gravestone with two porcelain transfer photos would love to send picture ..it is on marble

Reply

L. Woods

1/4/2024 03:24:22 pm

Emily, good work. As an interesting addition, the J.A. Dedouch Company used to make the miniature lockets for President Lyndon B. Johnson's family. A gentleman by the name of H. Lowell Dial purchased them from the Dedouch Company and sold them to the Johnsons. Most were of his grandchildren.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly