|

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Throughout the course of the nineteenth century, the New Orleans Jewish experience varied among individuals and families, from great successes to great defeats. For some, it was something one was born into: by mid-century, a number of families had developed deep roots in New Orleans commerce and culture. For men like Judah P. Benjamin and other merchants, lawyers, and factors, New Orleans was a place of opportunity among aristocrats and politicians. For others, however, New Orleans was a refuge, only slightly improved from the poverty and exclusion of the homeland from which they had fled. Among the Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who immigrated to New Orleans between 1840 and 1880, many found their new home to be wracked by destitution, disease, and an uncertain future. These immigrants formed their own communities, establishing a familiar cultural norm to ease their transition in the New World.[1] Two New Orleans stonecutters exemplify this wide spectrum of experience. Edwin I. Kursheedt, part of an influential Jewish family, was successful not only professionally but personally. Committed to charity and military service, he inherited his business from his father and carried it into the twentieth century. Alternatively, the carved signature of H. Lowenstein is nearly all that remains of this stonecutter’s legacy. It is likely that his time in New Orleans was brief, cut short by disease, war, or the search for better opportunities.

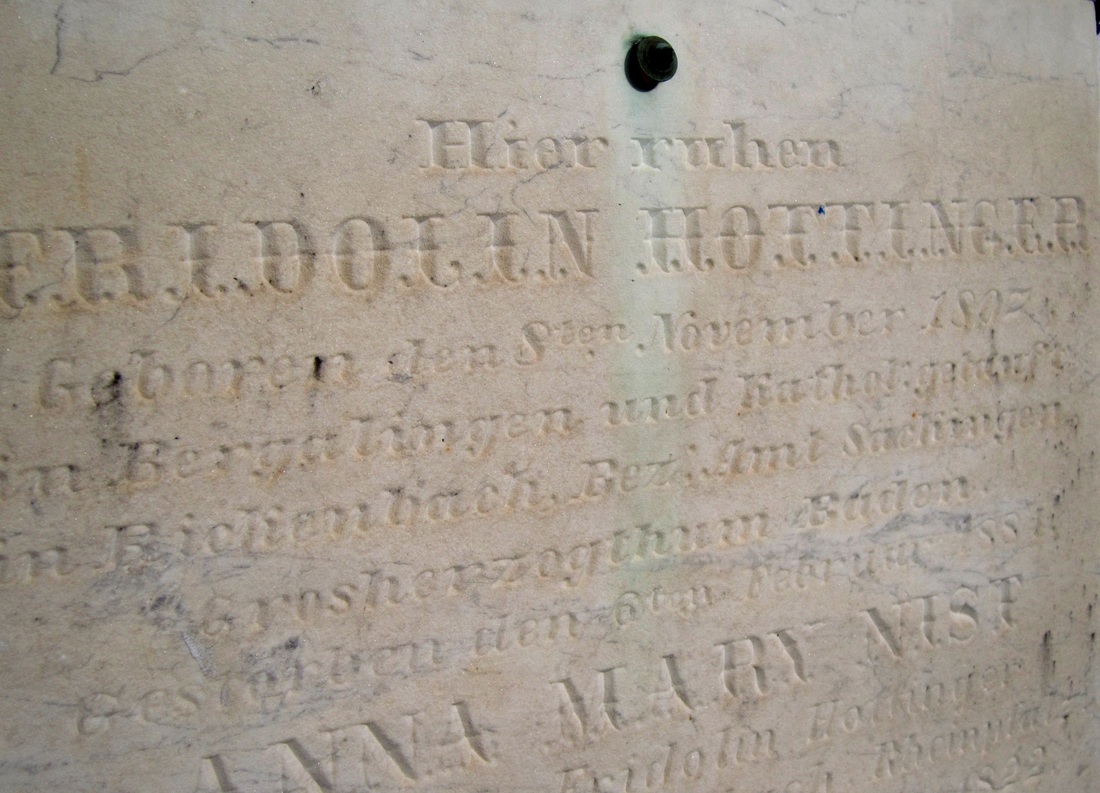

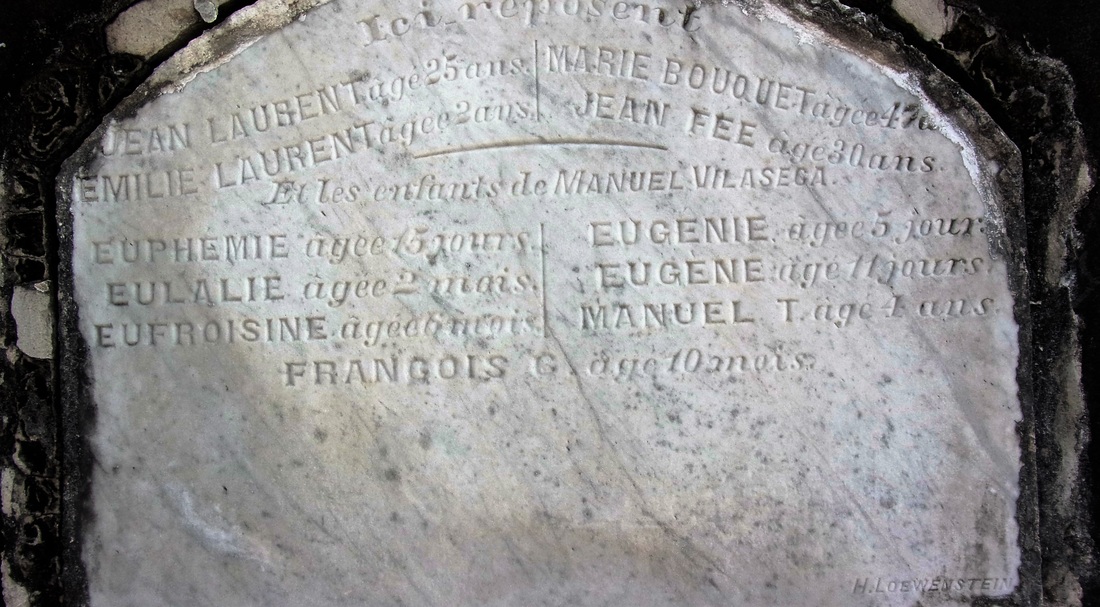

The address of H. Lowenstein’s business is recorded in directories and on his signed tablets as 195 and 197 Washington Avenue, which corresponds to the historic marble yard and shop located across Washington Avenue from Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. During the years Lowenstein held business there, other stonecutters and sextons advertised at the address, namely James Hagan and Philip Harty. Lowenstein also advertised himself as an undertaker at this address. Lowenstein’s carving style bears a resemblance to that of other contemporary German stonecutters, namely the Anthony Barret and his sons Charles and Frederick. These artisans carved in the German Fraktur style, or black-letter, and employed similar imagery of oak and laurel wreaths that are not found among the work of non-German craftsmen in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. These scant traces of Lowenstein in New Orleans indicate that he was likely a German-Jewish immigrant who served the community of the Fourth District, once part of the suburb of Lafayette. A number of German newspapers, including the Deutsche Zeitung and the Louisiana Straatszeitung, may have been the venue for his advertising. Considering he frequently carved closure tablets in German, it is likely that he aided more established craftsmen like Hagan and Harty with their business in the German immigrant community. Yet, after 1869, documentation of H. Lowenstein evaporates completely, suggesting that, like many other Jewish immigrants in the South, he may have moved elsewhere, or possibly died young in New Orleans.

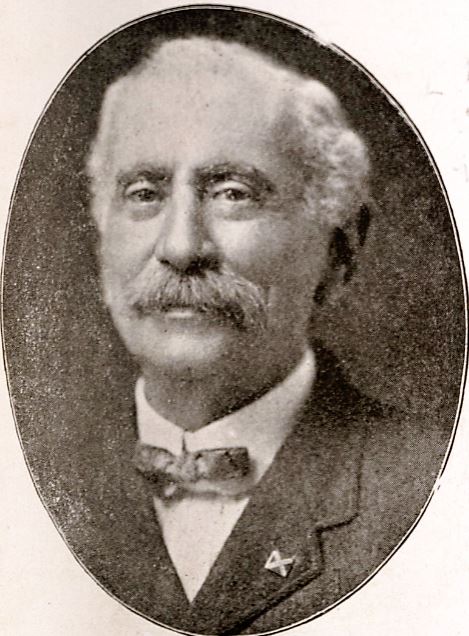

The business of Kursheedt & Bienvenu was among the most successful and prominent merchants of not only cemetery stonework and tombs but also hardware, commercial stonework, mantels, grates, and other items. By the 1880s, they owned not only a large show room on Camp Street but also a marble yard next door, at which at least thirty men were employed.

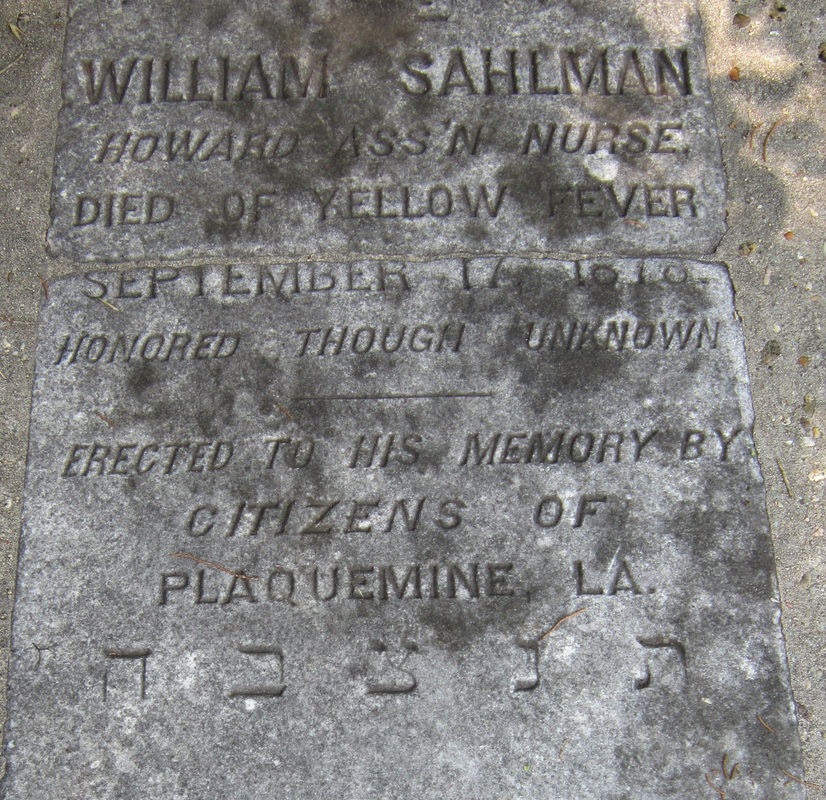

Much of Kursheedt & Bienvenu’s signed work can be found in Jewish cemeteries in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Alexandria, and Plaquemine, among other Louisiana towns. Within Jewish cemeteries, this work consists of headstones, as Jewish tradition prohibits above-ground burial. Yet Kursheedt & Bienvenu served clients of all religions and traditions. Among their most visible commissioned works is the Sercy tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Marked by a stone sarcophagus and located near the Washington Avenue cemetery gate, it is most notable for its epitaph: “Died of Yellow Fever,” a relic of the 1878 epidemic. J.G. Bienvenu left the business after 1888, and Edwin Kursheedt operated Kursheedt’s Marble Works until 1901.[8] Throughout these years, he served on various boards for Jewish Charities, including Touro Infirmary, the Hebrew Benevolent Association, and the Jewish Widows and Orphans Home.[9] He died in on February 21, 1906, at the age of sixty-seven, a veteran, merchant, benefactor, husband and father. He is buried in Dispersed of Judah Cemetery on Canal Street. It is unclear where or when H. Lowenstein died. The only tenuous hint points to an obituary published in the New Orleans Daily Picayune November 3, 1896, reporting the death of Henry Lowenstein, who died at the age of fifty-six in Cincinnati, Ohio. That a New Orleans newspaper reported his death suggests he once lived in the city, and may have been a young stonecarver on Washington Street in 1861, but no definitive documentation can support this possibility.[10] So these two artisans whose work is marked in New Orleans cemeteries died as they lived: one documented and memorialized, one lost in historic thin air, as were many immigrants who came and went from the Crescent City in the nineteenth century. [1] Bobbie Malone, “New Orleans Uptown Jewish Immigrants: The Community of Congregation Gates of Prayer,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 32, No. 3, Summer 1991, 239-287; Ellen C. Merrill, Germans of Louisiana (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2005), 225, 236.

[2] The signature “Löwenstein” can be found on the Fridolin Hottinger tomb, Quadrant 2, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1861 (New Orleans: Charles Gardner, 1861), 282; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1866 (New Orleans: True Delta Book and Job Office, 1866), 279; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1869 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1868), 399. [3] Bertram Wallace Korn, The Early Jews of New Orleans (American Jewish Historical Society: 1969), 247-249; “Mr. Israel Baer Kursheedt,” The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, Vol. X, No. 3, June 1852, 1. [4] Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 111-116. [5] Andrew Morrison, The industries of New Orleans: her rank, resources, advantages, trade, commerce and manufactures, conditions of the past, present and future, representative industrial institutions, etc. (New Orleans: J.M. Elstner & Co., 1885), 144. [6] Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 21, 1880, 5; “The Other Side: The Report Adopted by the State-House Commission Respecting the Work Done,” Louisiana Capitolian (Baton Rouge, LA), August 28, 1880. [7] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1887 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishers, 1887), 513. [8] Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1889 (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher, 1889), 532; Soards’ New Orleans City Directory, for 1901, Vol XXVIII (New Orleans: Soards Directory Co., Ltd., Publishers, 1901), 501. [9] W.E. Myers, The Israelites of Louisiana: Their Religious, Civic, Charitable and Patriotic Life (New Orleans: W.E. Myers, 1904), 103. [10] Daily Picayune, November 3, 1896, 4. See also, Emily Ford and Barry Stiefel, The Jews of New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta: A History of Life and Community Along the Bayou (History Press, 2012).

5 Comments

Bobbie Malone

10/9/2016 07:19:39 pm

Fascinating, and excellent research!

Reply

Joseph Bodenheimer

6/10/2017 07:00:17 pm

Hello Emily, my name is Joseph Bodenheimer, now living and working in Japan (originally from the city). I will be traveling back home to New Orleans, just back from Israel, doing genealogy work on my family. I located some of my families gave sites and just saw your well researched article. It is fascinating. I will be visiting several cemeteries, hope we can speak soon. All best, JMB

Reply

Emily Ford

6/12/2017 10:29:04 am

Hi Joseph! Thanks for your note! I'll be sending you an email to get in touch and learn more about your research. Thanks for reaching out!

Reply

tom

10/16/2019 03:07:16 am

l woud like advice

Reply

Emily Ford

10/21/2019 04:06:34 pm

Hi Tom! I'd be happy to help! Let me know what I can do, or email me at [email protected].

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly