|

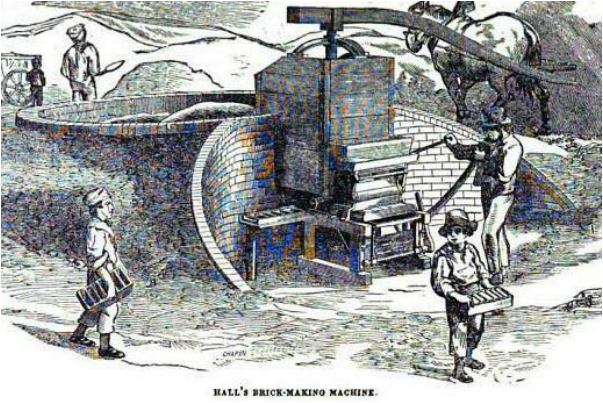

Part Two of Three The Little Red Row-house in the Cemetery By the 1830s, brickmaking processes were slowly industrializing in the Northeast and along the Eastern Seaboard. The introduction of hand-operated pressing machines led to the production of bricks with smoother edges. Other developments that tempered and cut clay using wires also arose. While these processes would eventually be introduced to New Orleans brickmakers, the clean, dense, fine-edged bricks they produced would be especially associated with northern cities like Philadelphia. In the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the “Protestant Section” is dominated by below-ground burials, a feature attributed to the cultural inclination of non-Catholics toward in-ground burial regardless of circumstances. Those burials which are accommodated by above-ground tombs are distinguished by construction using bricks that would sooner be at home in a northern row-house than a New Orleans tomb. The tombs of the Layton and Johnson families exhibit this brick for tomb construction. The tradition expanded beyond the 1830s, as exhibited by the multiple pressed red-brick tombs associated with Northern-born families in Cypress Grove Cemetery. Unlike traditional New Orleans tombs, these bricks were likely meant to be bare, without stucco. Brick Making Machines and Labor Beginning in the 1840s and likely earlier, brickmaking machines of all different types arose in New Orleans. The first machines were modifications of the “pug mill,” an apparatus by which brickmaking clay is churned and cured in order to make it suitable for molding. In 1848, John Hoey prominently advertised the construction of Hall’s “patent brickmaking machine” on his property near Bayou St. John.[1] This machine was essentially a pug mill in which clay was churned, cured, and extruded into molds. A number of additional brickyards developed along the Carondelet Canal, which ran from Bayou St. John past St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, terminating at Basin Street. Into the 1920s, “Carondelet Walk” featured a great deal of the city’s brick yards, from which bricks could be milled, fired, and transported for sale. Other brick yards thrived along the Mississippi River at Tchoupitoulas Street. In the Riverbend area, a brickyard operated a version of a Hoffman Kiln, another patented machine by which bricks were fired in a rotating sequence. By the 1850s, a number of steam-powered brick-making operations existed along the Gulf Coast in Biloxi, Mobile, and Thibodeaux, which supplied New Orleans markets.[1]

Prior to 1865, most of these operations, as well as smaller brick-making industries on plantation land, were operated by enslaved African Americans who were skilled in trade. In one instance, Gabriel Parker of St. Tammany Parish came to own his own brickyard after emancipation. In many other instances, freed tradesmen passed on their skills to their children.[2] [1] “Biloxi Fire Brick,” Daily Crescent, July 29, 1850, 3; Daily Picayune, June 3, 1866, 3; “Hoffman’s Brick Making Kiln,” Daily Picayune, March 8, 1867, 2; The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans Daily Picayune: 1903), 41; “Brickmaking Machine,” Thibodaux Minerva, January 21, 1854, 3. [2] Ellis, St. Tammany Parish: L’Autre Cote du Lac, 159; Crary, J.W., Sixty Years a Brickmaker: A Practical Treatise on Brickmaking and Burning and the Management and Use of Different Kinds of Clays and Kilns for Burning Brick (Indianapolis: T.A. Randall & Co., 1890), 36.

3 Comments

Nicole Miller

1/28/2016 07:57:17 am

Very interesting! Despite the number of locally made soft bricks, didn't some continue to import harder bricks from the north?

Reply

1/28/2016 09:44:30 am

Absolutely! Pennsylvania reds show up all through the 19th century.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly