|

How New Orleans weathered one of the greatest plagues in history. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a worldwide emergency like that which took place in 1918. Modern-day fiction and sci-fi writers have materialized similar fears – there is no shortage of post-pandemic fiction. For example, the HBO series The Leftovers posits a world in which two percent of the world’s population has vanished, the Max Brooks novel World War Z injects zombies into a frighteningly realistic image of how civilization would handle pandemic catastrophe. The list goes on. But we so often forget that something like this did happen. In 1918, a strain of pandemic influenza swept the globe three times, infecting millions and killing five percent of the world’s population. Medical science today cannot pin down exactly where it began. One prominent theory states that H1N1 influenza began with swine farms in Haskell County, Kansas in late January 1918.[1] Like other incidents of mutated influenza virus “jumping” from livestock to humans, it could have fizzled out in the local population. Yet nationwide mobilization in response to the United States’ entry into World War I meant that military camps were ubiquitous and population movement intensified. Influenza was transported to Camp Funston, Kansas, where it spread to other camps, other towns. The first wave of influenza traveled from the United States to Brest, France, in April 1918. Within the next month, it spread to Spain. Spain, neutral during World War I, was less likely to censor press reports of the disease. Hence, although the U.S., Britain, and France saw just as many cases of influenza, such incidents were not reported. The uneven press coverage created the appearance of the disease originating in Spain, giving it the incorrect moniker “Spanish Influenza.[2]” Influenza was documented in China and India by May 1918. The spring wave, however, was comparatively mild. The second wave of Fall 1918 would be devastating. As the summer of 1918 wore on and Allied victories in Europe continued, state and federal medical officials assumed disaster had been averted.

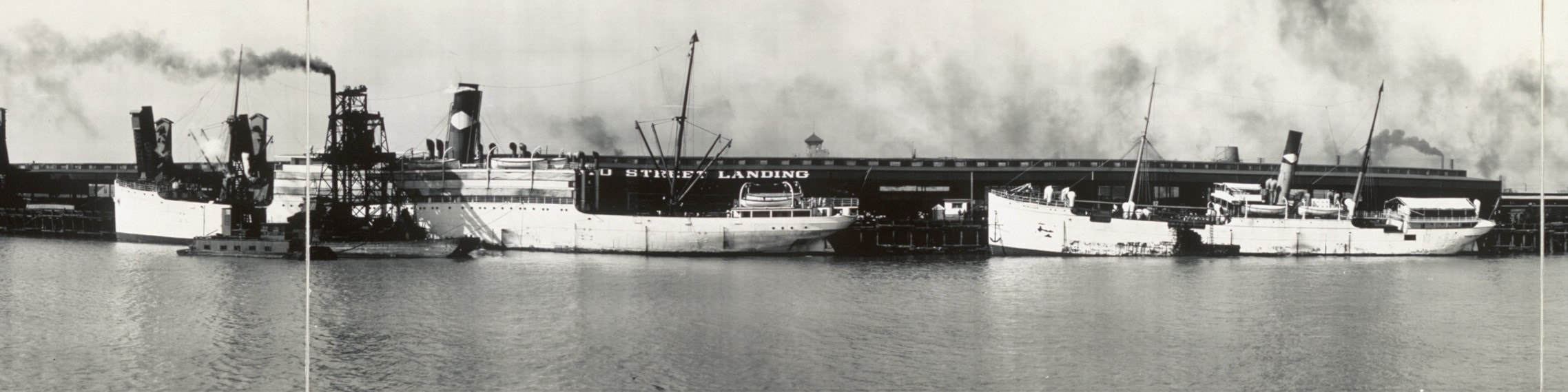

Attempts to quarantine the sick and curb the spread of influenza were often thwarted by the pressures of total war. In one especially salient instance, insistence from upper-crust social circles in Philadelphia caused medical leaders to allow a War Bonds parade to take place, despite the mounting evidence of an influenza epidemic. New cases of the illness soared in the days after this large public gathering. In metropolitan areas, the flu jumped from military to civilian populations, and then spread. One hundred years ago this month, influenza arrived in New Orleans. The Harold Walker and the Metaphan Boston’s first cases of influenza would arrive in late August 1918, likely originating from Navy traffic at Commonwealth Pier or from nearby Camp Devens.[5] On August 27, the Pan-American Oil Company tanker Harold Walker departed Boston for Tampico, Mexico. En route to Mexico, the steamer’s crew began to fall ill, with at least three sailors dying at sea. It is likely that the first influenza cases in Tampico were a result of contact with the Harold Walker’s crew.[6] On its return voyage to Boston, the Harold Walker stopped in New Orleans around September 16. The city Board of Health was notified the vessel had influenza on board and was directed to drop anchor in the middle of the Mississippi River as a means of quarantine. Three more sailors had died at sea en route to Louisiana, including seventeen year-old New Orleans-native John James Louis Orthmann. After docking, four men were transported to Charity Hospital for influenza treatment. Hours after that transport, the captain of the Harold Walker requested ten more of his crew be hospitalized.[7] Days later, around September 18, the United Fruit Company tanker Metaphan arrived in New Orleans from Colon, Panama. It, too, had influenza on board. Of the fifty-one soldiers, fifty civilians, and eighty-six crew on board, eleven were ill with influenza – all of whom were soldiers. Like the Harold Walker, the Metaphan was quarantined, but only for twenty-four hours. The ship carried perishable bananas, which could spoil if left on board much longer.[8] The Metaphan unloaded its cargo in port, but its passengers remained quarantined until September 22, when all but two were cleared to disembark.[9] The remaining two passengers had been found to be carriers of influenza based on throat swabs conducted on all aboard. These throat swabs identified the presumed cause of influenza at the time – a bacterium known as Pfeiffer’s bacillus or Bacillus influenzae. It was not until the 1930s that the influenza virus was isolated. The second wave of influenza pandemic, more virile and deadlier than the first, likely arrived on either the Harold Walker or the Metaphan. However, other cases had already been identified in Louisiana. The spread of pandemic influenza in 1918 was inevitable in a port city like New Orleans. Its deadliness would be determined by the response that came afterward. The Great War Epidemic disease had been commonplace in New Orleans since the city’s founding. Throughout the nineteenth century, waves of cholera, yellow fever, typhoid, and others were a yearly occurrence – with some years much worse than others. The city had even suffered in the influenza epidemic of 1830-1832. Since the late 1860s, New Orleans had seen waxing and waning efforts to curb the spread of disease. Beginning with the sanitarian movement brought by Northern military occupation in the Civil War and expanding with growing understanding of germ theory, measures to combat epidemics were advancing. Slaughterhouses and sewage disposal were regulated to stop the spread of intestinal maladies like cholera and typhoid. Cisterns were covered and eventually eliminated after the mosquito was identified as the vector for yellow fever. A vaccine for typhoid was developed in 1896. The last yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans was more than ten years in the past.[10] In 1918, public health officials in Louisiana had expected the new virile strain of influenza to spread to New Orleans. However, some presumption existed that New Orleans’ epidemic would be mild given the warmer climate. This was to be proven tragically false. The pandemic peaked in New Orleans from mid-September to mid-November 1918. In the United States, only Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, both overwhelmed by the influenza epidemic, had higher death rates than New Orleans.

On October 2, Camp Martin was reported to have forty ill soldiers, most of which had recently travelled from Arkansas. Camp officials wrote the outbreak off as malaria. Simultaneously, Camp Nicholls reported it had a dozen soldiers with “bad colds,” likely caused by the troops having travelled in the rain. No quarantine was issued. The president of the New Orleans Board of Health, Dr. W.H. Robin, was reported to be ill with influenza.[12] On October 4, Charles Brookman, a twenty-four year-old New Orleans native, died of influenza at Camp Beauregard near Opelousas. Camp Beauregard was reported to have hundreds of cases of the illness as troops continued to be transported outward to other bases. Brookman was buried in St. Roch Cemetery No. 1.

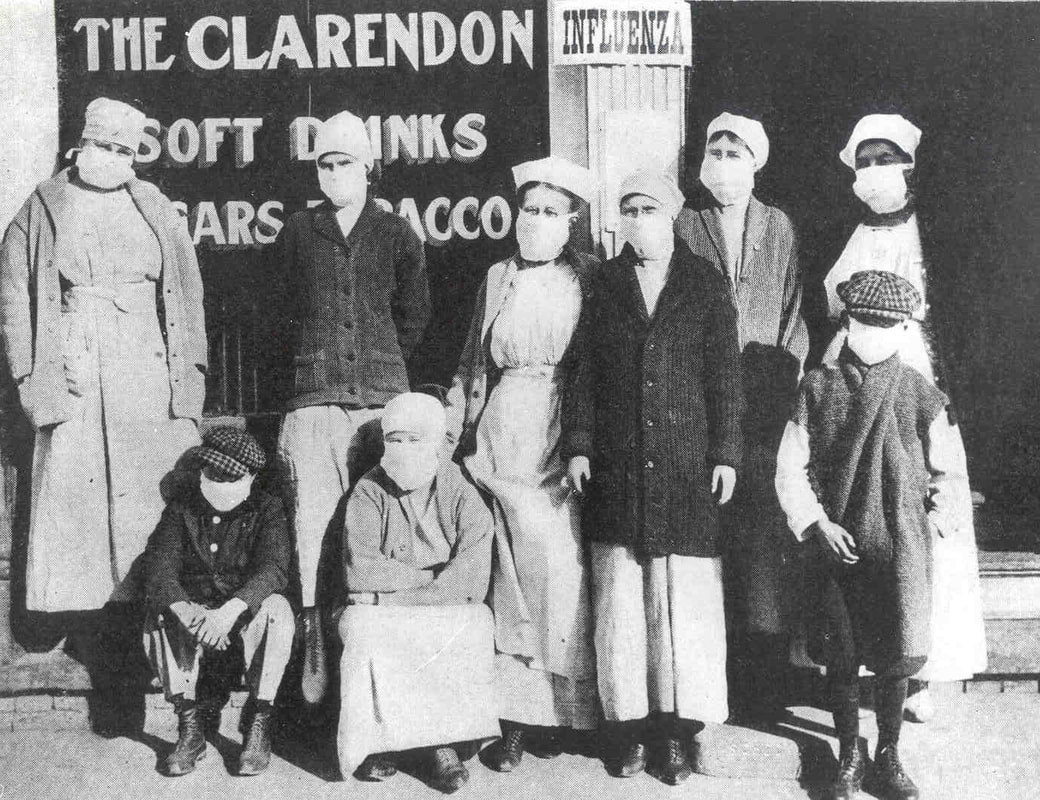

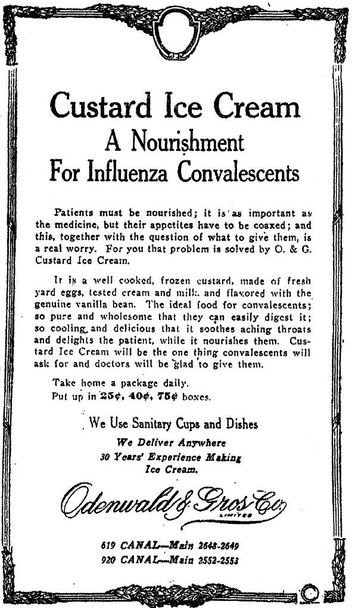

New Orleans Fights the Pandemic The Great War which had been the tinderbox for pandemic flu had also laid the infrastructure with which to combat it. Popular support of the war, bolstered by governmental and private boosting, meant that the Red Cross was heavily staffed and hospitals supplied. Fraternal organizations were poised to do their part for the war effort, which translated into doing their part fighting the epidemic. All citizens were called upon to buy Liberty Bonds, to conserve commodities like gasoline, and to be ever vigilant, for “every idle hour helps the Kaiser in his damnable attempt to enslave the world.”[15] In the first days of October 1918, the Red Cross pledged to make 50,000 gauze face masks for use in influenza wards throughout the city.[16] State and municipal public health officials instated mandatory reporting for influenza, although complaints continued through October that insufficient reporting stymied epidemic response. On the single day of October 8, more than two thousand new cases of influenza were reported by local doctors. The next day, the boards of health instated a closure order for all public gathering spaces including dance halls, ice cream parlors, public meetings, movie theaters, churches, and schools. Universities were not required to close, but restricted activities to only those associated with the military. The newspaper reported that Charity Hospital had two hundred cases of influenza with two floors of the hospital dedicated to their care.[17] Streetcars were ordered to run at half-occupancy to prevent overcrowding, which was difficult because too many streetcar operators were sick themselves.[18] Less than a week after the ban on public gathering, the city experienced shortages of soup and ice cream. Milk was in even shorter supply.[19] Streetlamps were extinguished to prevent nighttime gatherings of people. The epidemic in New Orleans, like in other cities, was even thought to have caused the crime rate to plunge. In the face of the ramping epidemic, the Red Cross and the US Public Health Service moved to convert a building on the Touro Infirmary campus for the exclusive care of influenza patients. It opened on October 20. The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks supported home visits and medication dispensaries, as well as cancellation of their public gatherings.[20]

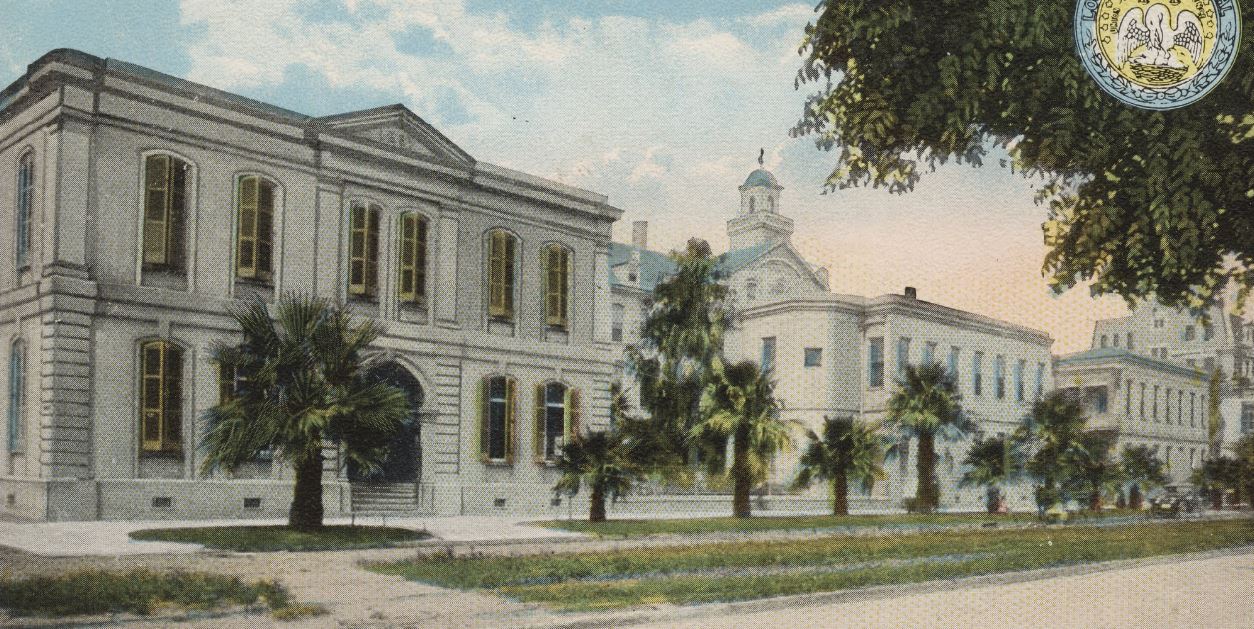

On October 22, Bertha Roy Vergeron, twenty years old and married less than a year, died of influenza. She was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. All Saints’ Day 1918 In the waning days of October, rapid mobilization of federal, local, and private organizations paired with restrictions on public gatherings appeared to be paying off. A vaccine was being offered through Tulane University and Charity Hospital, although its efficacy was unclear. The vaccine, developed in Boston, was a serum extracted from the blood of recovered influenza patients. Although used nationwide, the vaccine is not understood to have directly combated the H1N1 influenza virus.[23]

In December, the disease would make its third and final trip around the world. Charity Hospital was once again dedicated entirely to the care of influenza patients. However, the severity of this third and final epidemic would not be as severe and was declared concluded by early February 1919. During the fall and winter epidemics of 1918, fifty-four thousand people in New Orleans contracted influenza – fourteen percent of the entire city’s population. Three thousand four hundred and eighty-nine of these people died of their illness and were buried in family tombs, wall vaults, or in the vast unmarked space of Charity Hospital Cemetery on Canal Street. Any visitor through the aisles of a New Orleans cemetery will pass an epitaph that recalls the terrifying month that brought New Orleans to a halt a century ago. Today these epitaphs serve as memorials to both deep personal and communal grief. [1] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 93.

[2] Barry, The Great Influenza, 169-172. [3] Ibid., 178. [4] Ibid., 178, 181, 184. [5] Barry, The Great Influenza, 186. [6] Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (Boston: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 63; “Movement of the Mexican Oil Fleet,” Oil Trade Journal, Vol. 13, No. 10 (October 1922), 127. [7] “Mexican Steamer Comes into Port with Influenza: Fourteen Men of Crew Suspected of Being Victims of Spanish Influenza,” Times-Picayune, September 18, 1918, 13. [8] “Fruit Steamer with Influenza Aboard Arrives: Eleven Cases of Disease are Found When Vessel Reaches Station,” Times-Picayune, September 21, 1918, 5. [9] Health Officers Release 48 From Ships Sick List,” Times-Picayune, September 22, 1918, 13B. [10] Urmi Engineer Willoughby, Yellow Fever, Race and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2017), 145. [11] “Influenza Goes in New Orleans Home to Get Victim: First Resident of City to Succumb to Epidemic is Morris Maurer,” Times Picayune, September 29, 2018. [12] “Steamer Brings 56 cases of Dread Malady,” Times-Picayune, October 2, 1918, 9. [13] “Lieut. Bourdet Dies; Ill But Short Time,” Times-Picayune, October 9, 1918, 2. [14] “Death Follows Brief Illness,” Times-Picayune, October 9, 1918, 5. [15] “How To Win,” St. Martinsville Weekly Messenger, October 26, 1918, 2. [16] “Chapter Workers are Busy Making Hospital Masks,” Times-Picayune, October 4, 1918, 12. [17] “All Shows, Churches, are Ordered Closed to Fight Epidemic: Cases in the State Total 100,000,” Times-Picayune, October 10, 1918, 1, 10. [18] “Carmen Stricken Thirty Each Day,” Times-Picayune, October 16, 1918, 14. [19] “Influenza Causes Shortage in Milk,” Times-Picayune, October 14, 1918, 6. [20] “Influenza Halts Italian Red Cross Benefit Schemes,” Times-Picayune, October 9, 1918, 5. [21] “Sacrifice Costs Physician’s Life,” Times-Picayune, October 16, 1918, 15. [22] “Theda Bara Visits Convalescent Camp: Goes Among Soldiers with No Apparent Thought of ‘Flu’ Danger,” Times-Picayune, October 22, 1918, 5. [23] “Funds for Fight Against Epidemic Asked from State,” Times-Picayune, October 21, 1918, 1, 10; John Barry, The Great Influenza, 260. [24] “Regular Services at All Churches to Begin Sunday,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1918, 1. [25] “Orleans Observes All Saints’ Day,” Times-Picayune, November 2, 1918, 6. [26] “All Souls’ Day Observed,” Times-Picayune, November 3, 1918, 21.

5 Comments

James

1/25/2020 10:54:40 pm

I just wanted to say thank you, for taking the time to conduct the background research for your article, it was informative.

Reply

Amy Braun

3/17/2020 12:41:36 pm

Thanks for this article. It mentions contribution and death of my great grandfather’s, Dr. JM deMahy. My great grandmother, his wife, also died during the epidemic when she contracted the disease when retrieving his body. This left my 2 yr old grandfather orphaned. He later became a Doctor and fathered 12 children.

Reply

Emily Ford

3/17/2020 02:27:35 pm

Thank you for your note Amy! It is so moving to hear the rest of Dr. deMahy's story. Also, your family's tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 is beautiful.

Reply

Stacia Shepherd

3/23/2020 01:04:03 am

This article was very informative! My husband’s grandmother’s mother died during the Flu epedemic in New Orleans near Jackson Barracks! His grandmother was only 6 or 7 yrs old! His grandmother had to go live with the nuns and was raised by the nuns because of her mom during from the Spanish Flu during 1918 in New Orleans! So sad and here we are full circle fighting another pandemic with the covid-19 virus of 2020! May we learn from the past to self quarentine and flatten the curve!

Reply

Emily Ford

3/24/2020 05:56:43 pm

Thanks so much for the note Stacia! It is so amazing to hear stories from the descendants of those who were affected by the 1918 epidemic. The memory of that experience is so real and relevant, as you said. Taking the lessons of history to heart is truly a beautiful way to honor ancestors. Stay well!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly