|

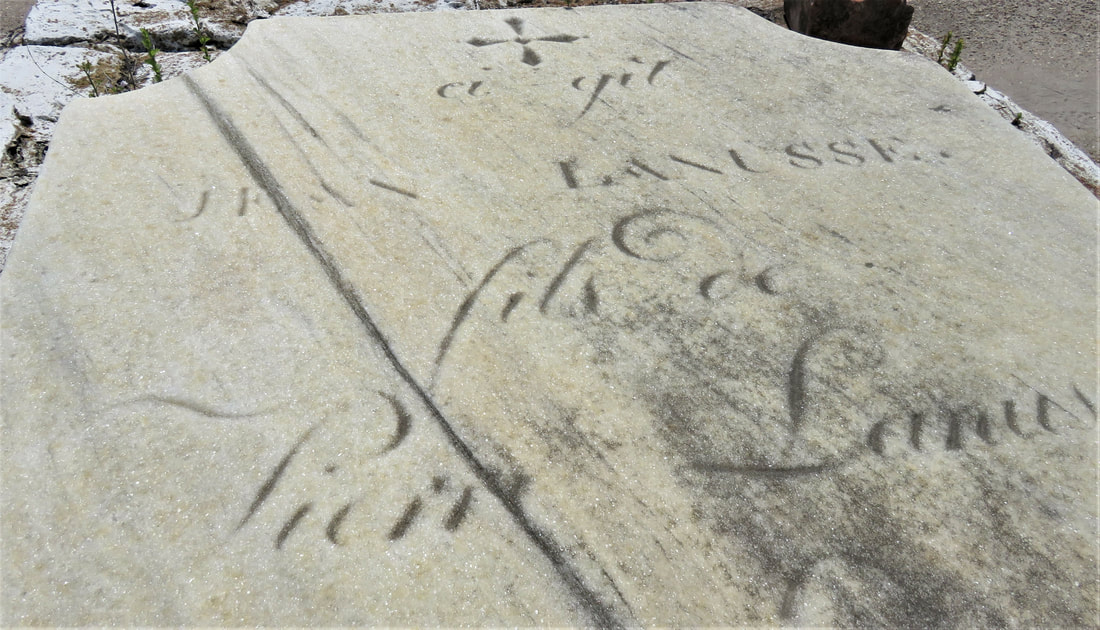

How one of New Orleans best-known cemetery stonecutters chose his flower symbols. Iconography is a favorite interest of cemetery researchers and visitors alike. Its symbolic images can be religious (Cohenim hands and water pitchers in Jewish iconography, for example), fraternal (inverted pentagrams and all-seeing eyes, anyone?), occupational, or, in modern times, even outrightly representative of the interests of the deceased. The symbolism of flowers and plants has a special place in the cemetery landscape. The appearance of a flower offers its own particular aesthetic, while suggesting a larger theme: loyalty, faith, or a life cut short, for example. The origin and popularity of floral symbolism has roots in ancient Greece and flourished in the nineteenth century. New Orleans stonecutters utilized flowers prolifically during this period. Craftsmen from Paul Hyppolyte Monsseaux to Joseph Callico to Albert Weiblen included them in their tablets. But one stonecutter’s use of floral iconography stands out even among his contemporaries. The work of Florville Foy, whose work spanned from the 1840s to the turn of the twentieth century, can be distinguished for its floral work. For this researcher, the appearance of a pansy on a tablet almost guarantees a Florville Foy signature. In this post, we examine Florville’s flowers. Florville Foy (1820 – 1903) Among all the stonecutters of New Orleans, Florville Foy has probably been most studied. This is almost entirely due to the work of historian Patricia Brady in the 1990s. Her diligence in learning the personal and professional details of Foy’s life and documenting them through academic publication is one reason Foy is seen as one of the most prominent of nineteenth century New Orleans stonecutters. Her research is synopsized here, but we encourage a thorough reading of her original article in the Southern Quarterly, Vol. XXXI, No. 2, Winter 1993. Florville Foy was a free person of color; the son of French plantation owner and sculptor Prosper Foy (1787-1854) and Azelie Aubry (c. 1795-1870), a free woman of color.[1] Florville was not the only free man of color to work in New Orleans cemeteries in the nineteenth century. Joseph Frederick Callico (~1828-1885), who worked primarily in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 with a brief stint as the sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, was also a free man of color working in New Orleans cemeteries prior to the abolition of slavery.[2] Stonecutter Daniel Warburg (1836-1911) was the son of an enslaved Cuban woman and a German Jewish father. Florville, however, was likely the only man of color working in New Orleans cemeteries who was trained in France in the craft of sculpture.[3] Prosper Foy was himself a stonecutter in New Orleans cemeteries up until the 1830s. His signature is found with the very few remaining pre-1830s examples of New Orleans cemetery stonework, among his contemporaries, Lucas and Jean-Jacques Isnard (1798-1859). Florville Foy joined his father at his marble yard on Basin and St. Louis Streets in 1836, with Prosper retiring two years later.[4] Over the next twenty years, Florville would expand the marble yard across Rampart Street. He worked in cemetery marble sculpting, with a staff of skilled craftsmen, until the turn of the century. Florville Foy died in 1903 and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. Over his nearly sixty-year career, Florville Foy worked across the spectrum of New Orleans cemetery architecture. He carved simple headstones and decorated tombs of the highest style and designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly. His work is found throughout Louisiana (as far as Natchitoches) and in Gulf Coast cemeteries in Mississippi and Florida. In Louisiana, Foy was like many stonecutters of his day in that his primary customers were his colinguists – French-speakers or otherwise associated with French Creole culture. In New Orleans, his work is primarily found in the French-oriented St. Louis Cemeteries, although some examples are present in Anglo-American-oriented cemeteries like Cypress Grove and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Florville Foy’s work was of course influenced by his French training as well. And while that may have contributed to his usage of floral motifs, they were more broadly a sign of their times. Florville’s career, it just so happened, fit perfectly within the Victorian Era. The Victorian Language of Flowers The Victorian era was named for Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, who assumed the throne in 1837 and reigned until her death in 1901. In a broader sense, the period refers to a cultural era in both Europe and North America that embraced certain trends in fashion, culture, literature, and science. For funerary and cemetery traditions, it meant the rise of rural cemeteries, romanticism, and the “beautification of death.”

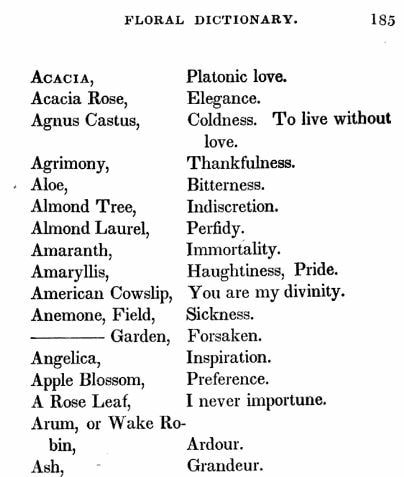

Thus it is natural that floral symbolism found its way into cemetery stonecutting. Bouquets of forget-me-nots, pansies, roses, and other blooms on a cemetery tablet could indicate love, memory, and loyalty.

More than any other stonecutter, Florville Foy’s relief carvings depicted not only flowers but bouquets of flowers, mostly with their stems joined but sometimes in a vase or urn. This approach allowed Florville to pack several symbols into one design, resulting in a carving both visually and symbolically rich. Among Florville’s most common floral symbols are the following:

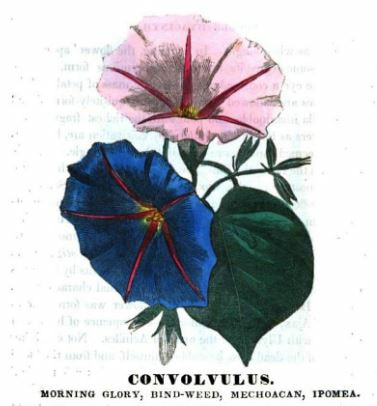

LILIES: Florville Foy’s lilies appear either as wide-open five-petaled narcissi or as four-petaled flowers with enormous stamens. This confusing representation makes identification difficult. The carver may have been attempting to represent a calla lily which, while present in Europe in the nineteenth century, was not widely available in the United States until after the 1860s. In general, lilies represent purity and, in some cases, marriage.[11] MORNING GLORY: Plants among the more than one thousand species commonly called “morning glory” have two symbolic behaviors in common: they bloom early in the morning and whither by mid-day, and they are vines that cling tightly to anything they bind to. Historic floral dictionaries refer to these flowers as symbolic of “affectionate attachment” and the impermanence of beauty.[12] SUNFLOWER: While sunflowers may be rare to find in cemetery iconography, Florville Foy did utilize at least one – the tomb of Pierre Pradat in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, likely constructed in the 1850s. In historic floral dictionaries, the sunflower is noted to represent “watchfulness, flattery and devotion,[13]” owing to its tendency to turn the face to follow the sun throughout the day. Other nineteenth century floriographies refer to its symbolism as that of “pure thoughts[14]” or, alternatively, “false riches[15].” Modern histories of floral symbolism (specifically in cemeteries) state that the sunflower’s dependable watch over the sun throughout the day may be a Catholic symbol of the divine light of God, although it is difficult to find a nineteenth-century reference to such symbolism.[16]

[1] Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.: Master Marble Cutter and Tomb Builder,” Southern Quarterly, Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (Winter 1993), 10.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, Tenth Census of the United States, 1880 (National Records and Archives Administration), Roll 461, Page 234C, Enumeration District 36; State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History, Vital Records Indices; Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1861 (New Orleans: Charles Gardner), 89. [3] Brady, Patricia. “Black Artists in Antebellum New Orleans.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 32, no. 1, 1991, pp. 5–28. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4232862. [4] Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.: Master Marble Cutter and Tomb Builder,” Southern Quarterly, Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (Winter 1993), 11. [5] Mandy Kirkby, A Victorian Flower Dictionary: The Language of Flowers Companion (New York: Ballantine Books, 2011), 113; Douglas Keister, Stories in Stone: A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2004), 52. [6] John B. Newman, M.D., Illustrated Botany Containing a Floral Dictionary and a Glossary of Scientific Terms (New York: Fowlers and Wells, 1850), 192. [7] Keister, Stories in Stone, 54. [8] Newman, M.D., Illustrated Botany Containing a Floral Dictionary and a Glossary of Scientific Terms, 46-47; Kirkby, Victorian Flower Dictionary, 49. [9] Catherine H. Waterman, Flora’s Lexicon: An Interpretation of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers (Philadelphia: Herman Hooker, 1839), 41. [10] Ibid.; Newman, M.D., 186, 192; Keister, 43; Kirkby, 164. [11] Keister, 44; Newman, M.D., 189; Waterman, 126; [12] Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 41; Hermon Bourne, Flores Poetici: The Florist’s Manual (New York: Charles S. Francis, 1833), 86. [13] Bourne, 124. [14] Waterman, 194. [15] Newman, M.D., 194. [16] Keister, 54.

1 Comment

James Bollino

11/5/2019 03:59:13 pm

Great research and a wonderful story. There is so much hidden beauty in our New Orleans cemeteries and I truly appreciate your work. Thanks!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly